Abstract

Background and objectives:

Little is known about the economic burden of hypoglycemia in Belgium, or its related co-morbidities. This study aimed at estimating the cost and length of stay associated with hypoglycemia-related hospitalizations in diabetic patients in Belgium and the association between hypoglycemia and in-hospital all-cause mortality, incidence of traumatic fractures, depression, and cardiovascular diseases (myocardial infarction or unstable angina), using retrospective data from 2011.

Methods:

Patient data were retrieved from the IMS Hospital Disease Database, including longitudinal (per calendar year) information on diagnoses, procedures, and drugs prescribed in ∼20% of all Belgian hospital beds. The eligible population included all adult (<19 year) diabetic (both types) patients, further split between those with/without a history of hypoglycemia-related hospitalizations. Diabetes, hypoglycemia, and co-morbidities of interest were identified based on International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems Version 9 (ICD-9) diagnosis codes. All costs were extrapolated to 2014 using progression in hospitalization costs since 2001.

Results:

A total of 43 410 diabetes-related hospitalizations were retrieved, corresponding to 30,710 distinct patients. The average hospitalization cost was €10,258 when hypoglycemia was documented (n = 2625), vs €7173 in other diabetic hospitalized patients (n = 40,785). When controlling for age and sex, a higher mortality risk (OR = 1.59; p-value <0.001), a higher incidence of traumatic fractures (OR = 1.25; p-value = 0.009), and a higher probability of depression-related hospitalizations (OR = 1.90; p-value <0.001) were observed in hypoglycemic patients. A similar risk of cardiovascular event was observed in both groups, but hypoglycemic patients were more at risk of experiencing multiple events.

Conclusion:

Hospitalizations for hypoglycemia are expensive and associated with an increased risk of depression and traumatic fractures as well as increased in-hospital mortality. Interventions that can help reduce the risk of hypoglycemia, and consequently the burden on hospitals and society, without compromising glycemic control, will help to further improve diabetes management.

Background and introduction

Diabetes mellitus affected more than 382 million individuals worldwide in 2013, corresponding to ∼8.3% of the adult populationCitation1, with type 2 diabetes (T2DM) accounting for ∼95% of the casesCitation2. In 2008, more than 1.3 million people died from diabetes and its direct complications (mainly cardiovascular diseases), making it the 4th leading cause of mortality due to non-communicable disease in the worldCitation3. In Belgium, 620,218 patients were receiving anti-diabetic drugs in 2013Citation4, and it is assumed that many early-stage patients are not treated or even remain undiagnosed. Both prevalence of diabetes and associated mortality increase with age: according to statistics from the Belgian Health Care Payer (RIZIV-INAMI), more than 20% of the Belgian population above 65 years suffers from type 2 diabetesCitation5, while excess mortality attributable to diabetes (T1DM or T2DM) ranges from 2.3% in adult patients below 30 years to 16% in patients older than 70 yearsCitation6.

The limited long-term success of lifestyle programs in maintaining glycemic goals in T2DM patients (and their inefficiency in T1DM patients) suggests that the large majority of patients will require the addition of medications (insulins or oral anti-diabetic drugs) over the course of their diabetes in order to reach glycemic controlCitation7 and prevent the occurrence of diabetes-related complicationsCitation8. However, exact targets for glycemic control in hospital settings remain a matter of debateCitation7 and near-normal glycemic control by use of insulin cannot be achieved without a considerable risk of drug-induced hypoglycemiaCitation9,Citation10.

Hypoglycemia has a dramatic impact on patient’s quality-of-lifeCitation11. It may be associated with fallsCitation12, accidentsCitation13, diabetic shock or coma, depressionCitation14, dementiaCitation15, or psychological distressCitation16, and result in a higher risk of mortalityCitation17,Citation18, especially in patients with known T2DM and established cardiovascular diseasesCitation19. Hospitalization may be required in the most severe cases; oral hypoglycemic agents and insulins were responsible, respectively, for 10.7% and 13.9% of the emergency hospitalizations for adverse drug events in elderly patients (>65) in the US over the 2007–2009 periodCitation20. However, very little is known about the economic burden and co-morbidities associated with hypoglycemia in Belgian patients. The current study aimed at estimating the burden of hypoglycemia-related hospitalizations in T1DM and T2DM patients in Belgium, using retrospective inpatient data from 2011. The association between hypoglycemia and in-hospital mortality/incidence of specific morbidities, such as traumatic fractures, depression, and cardiovascular diseases, was also assessed.

Methods

Study end-points

The primary end-points for this study were the average cost and length of stay (LOS) associated with hospitalizations in adult diabetic patients experiencing an episode of hypoglycemia, both overall and split between cases with and without accidental fall and per age groups. Secondary end-points included the in-hospital mortality and the risk of cardiovascular events, depression, and traumatic fractures in diabetic patients with and without a history of hypoglycemia-related hospitalizations over the course of the calendar year.

Data source

This study was a retrospective database study of Belgian adult (above age 19) people with diabetes hospitalized at least once in the year 2011. The source of information was the IMS Hospital Disease Database (HDD). Since 1991, it is mandatory for Belgian hospitals to register diagnoses for each admission in a minimum basic data set (MBDS), to receive funding from the healthcare payer. These MBDS are captured via a Trusted Third Party (TTP) and collated into a national database. A sub-set of the database, consisting of hospitals that have given written authorization to do so, is anonymized (on both the hospital and the patient level) and transmitted to IMS, constituting the HDD. For the selected study period, the HDD comprises data on ∼20% of all acute hospital beds in Belgium, mainly located in the Northern part of the country. The panel of hospitals is representative in terms of hospital size and type of centers (general hospital vs academic hospitals). Studies using data from the HDD have been presented in numerous international congresses and published in peer-reviewed publicationsCitation21–23.

The unit in the HDD is the ‘hospital stay’, either in a day clinic setting (meaning that the patient does not stay overnight) or as a full hospitalization (at least one overnight stay in the hospital). Each stay receives a unique identification number. Data recorded at the stay level comprises the length of stay (LOS), the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems Version 9 (ICD-9) diagnoses and procedure codes, the length of stay in the different services and the type of discharge. Information on all the drugs invoiced over the course of the stay—including number of units and cost—is also documented. The database also includes demographic data at the patient level (sex and age classes: <1 year, 1–4, 5–11, 12–19, 20–29, 30–39, 40–54, 55–64, 65–74, and ≥75). Within 1 calendar year, all the stays related to the same patient in the same hospital can be tracked through a unique patient identification number re-initialized at the beginning of each calendar year; as a consequence, patient follow-up is limited to a single calendar year.

Population selection and identification of morbid events of interest

For the assessment of the primary end-point, all full hospitalizations with concomitant diagnoses (primary or secondary) of diabetes and hypoglycemia were selected in patients older than 19 years. Diabetes (both T1DM and T2DM) was identified in the database with ICD-9 code ‘250: Diabetes mellitus’. Hypoglycemia was identified with ICD-9 codes ‘250.3: Diabetes with other coma (including hypoglycemic coma)’; ‘250.8: Diabetes with other specified manifestations (including hypoglycemic shock)’ and/or ‘E932.3: Poisoning with insulin or antidiabetic agents’ (). Although the ICD9 coding system recommends using ‘E932.3’ on top of a code specific to hypoglycemia, hospitalizations where it was coded alone were also included in the study population.

Table 1. List of codes used for patient selection.

Accidental falls were identified through any of the codes corresponding either to falls (‘E880-E889’) or accidents (‘E800-E838’) ().

Calculation of hospitalization costs

For a given stay, the hospitalization costs consist of three components: drug costs, room/bed costs, and procedure costs. Drug costs were extracted directly from the database. Room/bed costs and procedure costs were obtained by merging the data from the database with average costs per APR-DRG (All Patient Refined-Diagnosis Related Groups)/severity level, as calculated from the financial data files that all the Belgian hospitals are legally required to send twice a year to the Belgian authorities. These costs are published on the website of the Ministry of Public Health (latest available: data year 2011Citation24). Costs were then extrapolated to 2014 based on the progression in costs per APR-DRG as observed between 2001 and 2011 in the same published data using a geometric extrapolation.

Secondary end-points

For the calculation of secondary end-points, a larger population including all adult patients (>19 years old) hospitalized in full hospitalization setting with a primary or secondary diagnosis of diabetes was selected. In-hospital mortality was assessed separately in hypoglycemia-related hospitalizations and other diabetes-related hospitalizations. Similarly, risk of cardiovascular events, depression, and traumatic fractures were calculated separately in patients who had at least one hypoglycemia-related hospitalization (defined as any hospitalization with a primary or secondary diagnosis of hypoglycemia) documented over the course of the calendar year (hereafter named ‘hypoglycemic patients’) and in patients with no such hospitalization documented. Cardiovascular events was a composite end-point defined as myocardial infarction (ICD-9 code 410), unstable angina (ICD-9 codes ‘411.1: Intermediate coronary syndrome’ and ‘413.0: Angina decubitus’), or ischemic stroke (APR-DRGs ‘045: Cerebrovascular accident with infarction’ and ‘046: Cerebrovascular accident and pre-cerebral occlusion without infarction’). Depression was identified with the ICD-9 code 311 (‘Depressive disorders, not elsewhere classified’) and traumatic fractures with ICD-9 codes 800–829 ().

Analytical approach

Data were analyzed using SAS software version 9 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). All unadjusted average values are reported with standard error. The statistical significance of cost differences between hospitalizations, respectively with and without accidental fall was assessed using a Wilcoxon non-parametrical test. For the secondary end-points, risk was calculated according to two methods; first, by dividing the number of subjects having at least one event by the number of subjects at risk (equivalent to a probability), then by dividing the total number of events by the number of subjects at risk (equivalent to the average number of events per patient).

The distribution of the number of morbid events (hospitalizations for cardiovascular event, depression, or fall) per patient was compared between patient groups using a Chi-square test. Probability associated to morbid events and mortality were compared using a logistic regression and controlling for sex and age classes. Odds-ratios (OR) were reported with their 95% confidence interval. Statistical significance was assessed with reference to an a priori α-level of 0.05.

Results

Study population

A total of 43,755 hospitalizations with a primary or secondary diagnosis of diabetes (corresponding to 30 995 distinct patients) were initially identified in the database. Two hundred and eighty-five patients were excluded due to age ≤19, thus resulting in a final eligible population of 30 710 patients (among which the proportion of male patients was 49.7%), adding up to 43 410 hospitalizations. Patients older than 65 represented 72.6% of the eligible sample.

Hypoglycemia was documented in 6.0% (n = 2625) of these hospitalizations (158 hospitalizations with diabetic coma, 2307 hospitalizations with hypoglycemia shock, and 160 with anti-diabetic agent poisoning coded as standalone, i.e. with no mention of hypoglycemic event), corresponding to a total of 2196 patients. A co-diagnosis suggesting an accidental fall was present in 11.2% (n = 294) of the hypoglycemia-related hospitalizations. Administration of insulin and other anti-diabetes drugs was reported in 53.3% and 35.4% of these stays, respectively. Over the course of the whole calendar year, the use of an anti-diabetic drug was documented in 79.5% of the hypoglycemic patients ().

Table 2. Distribution of documented use of insulin and oral anti-diabetic drugs in the eligible population over the course of the whole study period.

Cost and length of stay associated with hypoglycemia-related hospitalizations

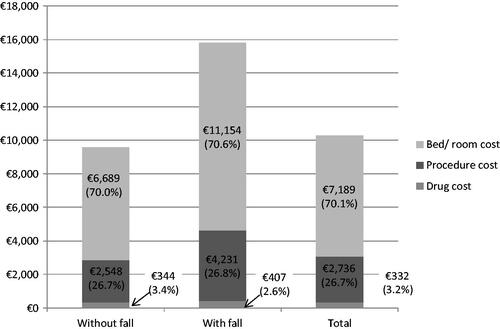

Overall, the average cost of a hypoglycemia-related hospitalization was €10,258 ± 324. The hospitalization cost was significantly higher when an accidental fall was documented (€15,792 ± 1212 vs €9559 ± 329 without fall; p-value <0.001). In both groups, room/bed costs represented ∼70% of the total cost, while procedure costs and drug costs accounted for ∼27% and 3%, respectively ().

The average length of stay was 16.2 ± 0.4 days. A longer length of stay was observed in hospitalizations with a fall (25.9 ± 1.8 days vs 15.0 ± 0.4 days without fall; p-value <0.001). On the other hand, the average cost of hospitalization in diabetic hospitalized patients without hypoglycemia was €7173, with an average length of stay of 10.1 days.

Both cost and length of stay tended to increase with subject’s age ().

Table 3. Average cost and length of stay (LOS) associated with hypoglycemia-related hospitalizations.

Mortality in diabetes-related hospitalizations with/without a co-diagnosis of hypoglycemia

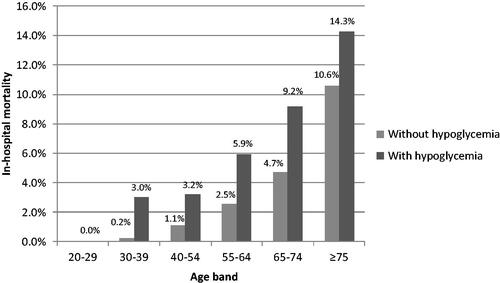

The unadjusted mortality rate in diabetes-related hospitalizations was 4.83% (1970/40,785) in the absence of a co-diagnosis of hypoglycemia and 6.06% (159/2625) when such a co-diagnosis was reported. Higher mortality was associated with hypoglycemia-related hospitalizations in every age range (). When controlled for age classes and sex, the mortality odd-ratio was 1.59 (1.38–1.85) for hypoglycemia-related hospitalizations, as compared to other diabetes-related hospitalizations (p-value <0.001).

Occurrence of morbid events

Hospitalizations with traumatic fractures were observed in 7.88% of hypoglycemic patients, vs 6.11% of patients without hypoglycemia (OR = 1.25 [1.06–1.47]; p-value = 0.009). The average number of fracture-related hospitalizations was higher as well in patients with hypoglycemia (0.085 per patient-year, vs 0.064 per patient-year in other diabetic patients; p-value <0.001). Depression-related hospitalizations were also more frequent in hypoglycemic patients (4.64% of the patients, vs 2.48% in the non-hypoglycemia population; OR = 1.90 [1.54–2.35], with a p-value <0.001); a similar pattern could be observed with regards to the number of events (0.054 and 0.028 depression-related hospitalizations in patients with and without hypoglycemia, respectively; p-value <0.001). The risk of cardiovascular event was similar between the groups (crude incidence rate of 7.38% vs 7.33% in non-hypoglycemic patients; OR = 0.98 [0.83–1.16], with a p-value = 0.801 when adjusting for age and sex). However, the probability of having more than one cardiovascular event over the course of the calendar year was higher in the hypoglycemic group, resulting in a higher event rate (0.090 per patient-year, vs 0.080 in the non-hypoglycemic group; p-value <0.001) ().

Table 4. Distribution of number of morbid events in patients with and without a history of hypoglycemia-related hospitalizations over the calendar year.

Discussion

In this retrospective database study, we used real life healthcare data to estimate the cost of a hypoglycemia-related hospitalization with and without an accidental fall, in Belgium. As secondary objectives, we used the same data to assess the risk associated with specific outcomes (mortality, traumatic fractures, cardiovascular events, and depression) in hospitalized diabetic patients with and without a history of hypoglycemia. A total of 30,710 hospitalized diabetic patients were retrieved from the Hospital Disease Database, among which 2196 had had at least one hypoglycemia-related hospitalization over the course of the calendar year 2011. When extrapolated to the whole Belgian population, this would represent a total of ∼150,000 hospitalized diabetic patients, with 11,000 of them experiencing at least one hospitalization with a co-diagnosis of hypoglycemia. Considering an estimated population of ∼620,000 treated diabetic patients in BelgiumCitation4, this would correspond to an annual incidence rate associated with hypoglycemia-related full hospitalizations of 1.78% across the whole diabetic population and 7.33% within the hospitalized diabetic patients. Both rates are in line with other published estimates; for example, a retrospective study conducted in a major university hospital in North America reported the occurrence of hypoglycemic incidents in 7.74% of the documented hospital admissionsCitation25.

Our study showed that the average cost of a hypoglycemia-related hospitalization was high (€10,258), and that this cost was even higher in patients having experienced an accidental fall. For the purpose of comparison, the average cost of a full hospitalization for an MI (a resource-intensive indication that constitutes a well referenced upper-threshold when discussing hospitalization costs), as calculated from the same database over the same period and using the same methodology, was equal to €7094. The higher cost associated with hypoglycemia-related hospitalization was a direct consequence of the relatively long length of stay observed in hypoglycemic patients. Earlier research conducted by Nirantharakumar et al.Citation18 showed that the average length of stay was 1.51-times higher in hypoglycemic patients than in other diabetic patients. A similar ratio was found in the present study (16.2 days vs 10.1 days in other hospitalized diabetic patients).

Our study showed that patients having experienced an episode of hypoglycemia were more at risk of being hospitalized for traumatic fractures during the same calendar year than other diabetic patients (OR = 1.25 [1.06–1.47]). This was in agreement with a retrospective study using healthcare claims from 361,210 patients in the USCitation11. That study showed a higher incidence of hypoglycemic events (4.7% of diabetic patients, not limited to in-hospital setting) and a higher odd-ratio (1.70) than our study, due to an older population (only patients above 65 had been included), which is in line with our observation that the fracture odds-ratio showed a tendency towards increasing with age. Unfortunately, the number of patients with fractures was not sufficient to detect a significant association between hypoglycemia and fractures within each age range in our study. In addition, our study was able to show a significant association between hypoglycemic events and hospitalizations for depression, with hypoglycemic patients having odds of being hospitalized with depression much in line with other recent dataCitation12.

On the other hand, no significant association could be detected between hypoglycemia and hospitalization for cardiovascular events. While the association between hyperglycemia and cardiovascular risk/mortality is now considered a well-established factCitation26–29, the association between intensive glycemic control therapy and cardiovascular diseases remains subject to debate in the scientific community, mostly due to the confounding effect of hypoglycemia. From a patho-physiological perspective, acute hypoglycemia is known to modify several hematological parameters, resulting in an increased risk of localized tissue ischemia, potentially leading to myocardial/cerebral ischemia and MICitation30,Citation31. While two large multi-countries clinical trials conducted in 2008 (ACCORDCitation32 and ADVANCECitation33) were not able to draw any significant conclusion regarding the effect of intensive glycemic control therapy on the incidence of major macrovascular events (defined as cardiovascular death, non-fatal MI, and non-fatal stroke), at least one retrospective study demonstrated the association between hypoglycemia, whether mild or severe, and cardiovascular riskCitation34. On the other hand, observations made during the 10-year post-trial follow-up of the UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPS) showed that early strict glucose control might generate a legacy effect on the long-term, eventually translating into protection from cardiovascular events, irrespectively of the increased rate of hypoglycemiaCitation35.

Our study also showed that inpatient all-cause mortality was significantly higher in hypoglycemic patients; however, the associated odd-ratio (1.59) revealed less impact of hypoglycemia than in other published resultsCitation18,Citation36. This is probably attributable to the fact that we only controlled for age range and sex. A more complex model, controlling for co-morbidities and treatment-related variables, might have yielded even more contrasted results. Nevertheless, the limited follow-up time and the study design did not allow for such a level of detail.

Some other limitations resulting from the nature of the database have to be acknowledged. First, the geographical coverage of the database includes mainly hospitals located in the Northern part of the country. This should not be a limitation as far as the secondary end-points are concerned, since these end-points are purely clinical and there is no reason to expect differences based on geographical location. The factor that could be variable across regions is the length of stay, the key driver of the hospitalization cost. However, a similar limited research conducted on an earlier version of the Hospital Disease Database (data of 2009, then covering the full country)Citation37 produced very comparable results on the items that were present in both studies and the length of stay associated with hypoglycemia-related hospitalizations was 17.3 days (vs 16.2 days in the present study).

Second, by definition, the database only contains information related to hospitalizations (i.e. leading to an admission, as opposite to ambulatory care); conversely, it is not possible to collect data on ambulatory visits or on out-of-hospital drug use. As a consequence, the rate of hypoglycemia presented here was restricted to these cases where either the hypoglycemia was severe enough to require a hospitalization, or the patient experienced the hypoglycemic event while already hospitalized. In contrast, cases where a patient visited the ER and this visit was not followed by a proper admission were not accounted for. Such cases represent a majority of the hypoglycemia-related ER visits, even severe casesCitation38.

For the same reason, only medications billed to the patient over the course of the hospitalization were documented in the database, as opposed to medications purchased in a retail pharmacy and brought by the patient at his admission. This likely resulted in an under-reporting of the use of oral anti-diabetic medications in our study population. Overall, use of insulin and other oral anti-diabetic drugs was documented in 53.3% and 35.4% of the hospitalizations with hypoglycemia, respectively, and, for 20.5% of hypoglycemic patients, no use of anti-diabetic drugs was documented over the whole study period. However, other studies have shown that spontaneous hypoglycemic episodes (i.e., not linked to anti-diabetic drugs) were observed in less than 1.5% of the diabetic patientsCitation39, so it is reasonable to assume that anti-diabetic medications were responsible for most of the hypoglycemic episodes, even in cases where the use of such drugs was not explicitly stated in the data. It is worth pointing out that the proportion of insulin-treated patients was significantly higher in hypoglycemic patients (36.6%) than in non-hypoglycemic patients (18.3%; p < 0.001), which would strongly suggest an association between hypoglycemia and the use of insulin.

Also, the fact that the ICD-9-CM code for ‘Anti-diabetic drug poisoning’ was coded in only 6.1% of the hypoglycemia-related hospitalizations should be interpreted cautiously. Part of the payment of the Belgian hospitals depends on the severity of the diseases they treat, as reflected by the case mix data they sent to the healthcare payer and from which the Hospital Disease Database constitutes a sub-set. Therefore, codes that might be of clinical interest but redundant or not relevant from a case-mix perspective are likely to be under-reported. For instance, additional codes related to ‘external causes of injury and poisoning’ (ICD9-CM codes E800 to E999) are not widely used since they are deemed redundant once the main diagnosis (hypoglycemic shock or hypoglycemic coma) has been reported.

Another limitation resulting from the coding in the database was the fact that we could not distinguish between T1DM and T2DM patients, especially in an adult population where both indications are mixed. Indeed, the coding of diabetes type requires the use of a fifth digit in the ICD9-CM diagnosis code (for instance, diabetic coma should be coded as 250.31 or 250.32 in type 1 and type 2 patients, respectively) and in practice this level of coding granularity was never applied in the database.

Despite these limitations, our findings indicate that hospitalizations for hypoglycemia are expensive and are associated with an increased risk of depression and traumatic fractures and an increased in-hospital mortality, especially in older patients (>55). Interventions that can help reduce the risk of hypoglycemia, and as a consequence decrease the patient’s morbidity and its burden on hospitals and society without compromising glycemic control, will help further improve diabetes management.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Novo Nordisk.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

TV is an employee of Novo Nordisk. PC and ML are employees of IMS Health. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

P.C. and M.L. are employees of IMS Health who were paid consultants to Novo Nordisk in connection with the development of this manuscript.

References

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Atlas, 6th edn. 2013. www.idf.org/diabetesatlas. Accessed December 2014

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (CDC). Diabetes: successes and opportunities for population-based prevention and control. Belgium: CDC, 2011. http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/aag/pdf/2011/diabetes-aag-2011-508.pdf. Accessed August 2015

- Global Status Report on noncommunicable diseases 2010. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010

- Rijksinstituut voor ziekte- en invaliditeitsverzekering. Farmaceutische kengetallen, farmaceutische verstrekkingen, ambulante praktijk. Belgium, 2013. 16th edn. 2014.

- INAMI. Le diabète en Belgique: état des lieux. Belgium, 2008. http://www.inami.fgov.be/information/fr/studies/study37/pdf/study37.pdf. Accessed December 2014

- Roglic G, Unwin N. Mortality attributable to diabetes: estimates for the year 2010. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2010;87:15-19

- Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: a patient-centred approach. Update to a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetologia 2015;58:429-42

- Hemmingsen B, Lund SS, Gluud C, et al. Targeting intensive glycaemic control versus targeting conventional glycaemic control for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;11:CD008143

- Van den Berghe G, Wilmer A, Milants I, et al. Intensive insulin therapy in mixed medical/surgical intensive care units: benefit versus harm. Diabetes 2006;55:3151-59

- Cryer P. The barrier of hypoglycemia in diabetes. Diabetes 2008;57:3169-75

- Rombopoulos G, Hatzikou M, Latsou D, et al. The prevalence of hypoglycemia and its impact on the quality of life (QoL) of type 2 diabetes mellitus patients (The HYPO Study). Hormones 2013;12:550-8

- Johnston SS, Conner C, Aagren M, et al. Association between hypoglycaemic events and fall-related fractures in Medicare-covered patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2012;14:634-43

- Marchesini G, Veronese G, Forlani G, et al. The management of severe hypoglycaemia by the emergency system: the HYPOTHESIS study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2014;24:1181-8

- Shao W, Ahmad R, Khutoryansky N, et al. Evidence supporting an association between hypoglycemic events and depression. Curr Med Res Opin 2013;29:1609-15

- Whitmer RA, Karter AJ, Yaffe K, et al. Hypoglycemic episodes and risk of dementia in older patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA 2009;301:1565-72

- Unger J. Uncovering undetected hypoglycemic events. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes Targ Ther 2012;5:57-74

- McCoy RR, Van Houten HK, Ziegenfuss JY, et al. Increased mortality of patients with diabetes reporting severe hypoglycemia. Diabetes Care 2012;35:1897-901

- Nirantharakumar K, Marshall T, Kennedy A, et al. Hypoglycaemia is associated with increased length of stay and mortality in people with diabetes who are hospitalized. Diabet Med 2012;29:e445-8

- Campbell K. Hospital strategies for insulin therapy with rapid-acting insulin analogs. Hosp Pharm 2011;46:580-90

- Budnitz D, Lovegrove M, Shehab N, et al. Emergency hospitalizations for adverse drug events in older Americans. N Engl J Med 2011;365:2002-12

- Chevalier P, Lamotte M, Joseph A, et al. In-hospital costs associated with chronic constipation in Belgium: a retrospective database study. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2014;26:368-76

- Body JJ, Chevalier P, Gunther O, et al. The economic burden associated with skeletal-related events in patients with bone metastases secondary to solid tumors in Belgium. J Med Econ 2013;16:1-8

- Nevens F, Colle I, Michielsen P, et al. Treatment of chemotherapy-induced anemia with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents in five European Countries. J Med Econ 2012;15:409-18

- Financial feedback per pathology. Technical cell the Belgian Federal Ministery of Health. SPF Santé publique, Sécurité de la Chaîne alimentaire et Environnement. https://tct.fgov.be/webetct/etct-web/anonymous?lang=fr

- Turchin A, Matheny M, Shubina M, et al. Hypoglycemia and clinical outcomes in patients with diabetes hospitalized in the general ward. Diabetes Care 2011;32:1153-7

- Soedamah-Muthu SS, Fuller JH, Mulnier HE, et al. High risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes in the U.K.: a cohort study using the general practice research database. Diabetes Care 2006;29:798-804

- Laing SP, Swerdlow AJ, Slater SD, et al. Mortality from heart disease in a cohort of 23,000 patients with insulin-treated diabetes. Diabetologia 2003;46:760-5

- Kannel WB, McGee DL. Diabetes and glucose tolerance as risk factors for cardiovascular disease: the Framingham study. Diabetes Care 1979;2:120-6

- Zhang P-Y. Cardiovascular diseases in diabetes. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2014;18:2205-14

- Wright RJ, Frier BM. Vascular disease and diabetes: is hypoglycaemia an aggravating factor? Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2008;24:353-63

- Snell-Bergeon J, Wadwa P. Hypoglycemia, diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Diabetes Techn Therapeut 2012;14(1 Suppl):51-8

- Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes Study Group (ACCORD). Effects of Intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2545-59

- ADVANCE (Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron Modified Release Controlled Evaluation) Collaborative Group, Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, et al. Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2560-72

- Hsu P, Sung S, Cheng H, et al. Association of Clinical symptomatic hypoglycemia with cardiovascular events and total mortality in Type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2013;36:894-900

- Gore O, McGuire D. The 10-year post-trial follow-up of the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS): cardiovascular observations in context. Diabetes Vasc Dis Resh 2009;6:53

- Garg R, Hurwitz S, Turchin A, et al. Hypoglycemia, with or without insulin therapy, is associated with increased mortality among hospitalized patients. Diabetes Care 2013;36:1107-10

- Lamotte M, Chevalier P, Vandebrouck T. The burden of hospitalizations due to hypoglycemia in Belgium. American Diabetes Association (ADA) 73rd Scientific Sessions, 2013, June 21-25, Chicago, IL, USA

- Geller AI, Shehab N, Lovegrove MC, et al. National estimates of insulin-related hypoglycemia and errors leading to emergency department visits and hospitalizations. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:678-86

- Lacherade JC, Jacqueminet S, Preiser JC. An overview of hypoglycemia in the critically ill. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2009;3:1242-9