Abstract

Objective:

Clinical practice guidelines support the use of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors panitumumab and cetuximab for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) after failure of other chemotherapy regimens, based on significant clinical benefits in patients with wild-type KRAS. The purpose of the analysis was to compare provincial hospital costs when using panitumumab vs cetuximab with or without irinotecan in this patient population using a Net Impact Analysis (NIA) approach.

Methods:

The NIA determined the total per patient cost of the reimbursed regimens of panitumumab vs cetuximab in British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario, and Québec. Utilization of healthcare resources related to EGFR inhibitor infusions, follow-up monitoring, and treatment of adverse events (AEs) were also included. Healthcare resource use including drugs, medical supplies, laboratory testing, oncology infusion time, and healthcare professionals’ time was obtained through expert consultation and the use was then multiplied by the province-specific cost of each resource. Numerous sensitivity analyses were conducted.

Results:

Based on the dosing regimens in place in each province, the total annual per patient cost of panitumumab ranged from $22,203–$32,600, while the total annual per patient cost of cetuximab treatment varied from $30,321–$40,908. Treatment with panitumumab resulted in lower costs in all cost categories including drug acquisition, infusion preparation/administration, patient monitoring, and AE management. Per patient savings with panitumumab ranged from a low of $3815 in British Columbia to a high of $10,603 in Ontario. In sensitivity analyses, panitumumab remained cost saving in all scenarios where the savings ranged from $150–$16,006 per patient.

Conclusions:

Treating chemorefractory mCRC patients with panitumumab rather than cetuximab reduced healthcare resource costs. Provincial healthcare savings achieved with the use of panitumumab could potentially be re-allocated to other cancer treatments, although further study would be needed to validate this assumption.

Introduction

Panitumumab and cetuximab are monoclonal antibodies that specifically target the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). Both are indicated for the treatment of patients with EGFR-expressing metastatic colorectal carcinoma (mCRC) with non-mutated (wild-type) KRAS after failure of fluoropyrimidine-, oxaliplatin-, and irinotecan-containing chemotherapy regimensCitation1,Citation2. The recommended dose of panitumumab is 6 mg/kg, given once every 2 weeks as monotherapy. The recommended dose of cetuximab is 400 mg/m2 initially, followed by a weekly dose of 250 mg/m2.

A phase III, randomized, controlled, multi-center trial of patients with mCRC that had progressed following treatment with fluoropyrimidine, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin demonstrated that panitumumab plus best supportive care (BSC) improved progression-free survival (PFS) compared with BSC alone (p < 0.0001)Citation3. After 2 years of follow-up, no difference was observed in overall survival (OS) and this finding was likely confounded by the study design whereby patients in the BSC arm with disease progression were permitted to cross over and receive panitumumab. A subsequent analysis done by Amado et al.Citation4 using the data from the pivotal trial by Van Cutsem et al. showed that the treatment effect of panitumumab on PFS in the wild-type (WT) KRAS group was significantly greater (p < 0.0001) than in the mutant group.

Cetuximab was similarly assessed in a trial comparing cetuximab to BSC in patients with mCRC who had been previously treated with a fluoropyrimidine, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin, or had contraindications to treatment with these drugsCitation5. In contrast with the panitumumab study, the cetuximab trial did not allow for patient crossover following disease progression. The study demonstrated an improvement in PFS and OS. As with the panitumumab trial, a retrospective biomarker analysis of the cetuximab study demonstrated that the WT KRAS status was required for cetuximab efficacyCitation6. An earlier study of cetuximab examined the relative efficacy of cetuximab monotherapy vs cetuximab plus irinotecan in mCRC patients refractory to irinotecanCitation7. In this study, the response rate was significantly higher with combination therapy compared with monotherapy (p = 0.007). The impact of the KRAS biomarker was unknown at the time of this analysis, so efficacy results from this study assessed by KRAS status remain unknown.

The two monoclonal antibodies have been compared directly in a randomized, multi-center, open-label, phase III study called ASPECCTCitation8. The study enrolled adult patients with WT KRAS mCRC, ECOG performance status of 0–2, prior irinotecan, oxaliplatin and fluorouracil-based treatment for mCRC, and no prior anti-EGFR treatment. Patients were randomized to panitumumab 6 mg/kg every 2 weeks (n = 499) or cetuximab 400 mg/m2 followed by 250 mg/m2 weekly (n = 500) until disease progression, intolerability, consent withdrawal, or death. Cross-over between treatments was not permitted. The primary end-point of the study was OS. The authors concluded that non-inferiority of OS was met, whereby median overall survival was 10.4 months (95% CI = 9.4–11.6) with panitumumab and 10.0 months (9.3–11.0) with cetuximab (HR 0.97; 95% CI = 0.84–1.11). The incidences of grade 3–4 skin toxicity, grade 3–4 infusion reactions, and grade 3–4 hypomagnesaemia for panitumumab vs cetuximab were 13%/10%, 0.5%/2%, and 7%/3%, respectively. The observed safety profiles between the two treatment arms were consistent with previously reported studies for both agents.

Differences in EGFR inhibitor drug acquisition cost between cetuximab and panitumumab were identified in the respective national oncology drug reviews previously conducted. However, it is not clear whether additional healthcare costs beyond drug acquisition were considered in the review. Because panitumumab is dosed once every 2 weeks and cetuximab is administered weekly, panitumumab may further reduce the cost of EGFR inhibitor in mCRC relative to cetuximab, due to differences in other healthcare resource consumption (e.g., nursing time, infusion supplies), thereby resulting in further savings to the overall provincial healthcare budget. The purpose of this analysis was to compare the total hospital costs of using panitumumab vs cetuximab in several provinces of Canada in the approved patient population using a net impact analysis (NIA) approach.

Patients and methods

A net cost impact model was constructed to capture all hospital costs related to the use of panitumumab or cetuximab in each province. The number of chemotherapy cycles included was based on either the allowable duration of treatment of mCRC according to reimbursement funding or according to expert opinion, in the absence of reimbursement, in each province. The duration of treatment ranged from 14–20 weeks. The costs included: the drug acquisition costs; costs related to preparation and administration of the medications; patient follow-up monitoring costs; and costs related to the treatment of adverse events (AEs). The provinces included in the analysis were British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario, and Québec.

The analysis was conducted from the perspective of the provincial hospital or cancer care budgets. Physician fees were not included because they are covered by the provincial health ministries rather than the hospitals or cancer care centres. Similarly, costs to determine patients’ KRAS status (i.e., WT or mutant) were not included because these costs are generally borne by the manufacturers of the EGFR inhibitor, occur prior to the decision regarding which EGFR inhibitor to use, and are the same, irrespective of which EGFR inhibitor will be used in the KRAS WT patients.

The time horizon for the analysis (14–20 weeks) was based on the standards of care in each province regarding the median number of infusions of each EGFR inhibitor that would be recommended. According to the pivotal studies, the duration of treatment required to derive a benefit in PFS was 7 biweekly cycles with panitumumab monotherapyCitation3, and 16 weekly cycles with cetuximab monotherapyCitation5. However, the clinical practices and EGFR inhibitor reimbursement in place in each province vary as follows: British Columbia recommends 10 infusions of panitumumab or cetuximab plus irinotecan where both regimens are infused every 2 weeks; Alberta recommends seven infusions of panitumumab biweekly or 14 infusions of cetuximab weekly; Manitoba recommends 10 biweekly and 20 weekly infusions of panitumumab or cetuximab, respectively; Ontario recommends nine biweekly infusions of panitumumab or 18 weekly infusions of cetuximab plus nine biweekly infusions of irinotecan; clinicians in Québec recommend seven infusions of panitumumab biweekly or 16 infusions of cetuximab weekly. The dosing regimens selected for the analysis were based on the funding protocols in place in each province that are aligned with the dosing schedule approved in the respective product monographsCitation1,Citation2 (except in British Columbia where cetuximab is dosed biweekly rather than weekly).

outlines the calculations used to derive the total average dose of panitumumab or cetuximab required per infusion. Briefly, the recommended dose according to each product monographCitation1,Citation2 was multiplied by a commonly assumed body weight (70 kg) or body surface area (1.73 m2). The total dose required per infusion was then divided by the number of milligrams per vial of the available formats for each EGFR inhibitor. The cost of the EGFR inhibitor treatment per cycle was then multiplied by the respective number of cycles of each treatment funded in each province.

Table 1. Calculated average EGFRi dose and number of vial requirements in each province.

The average utilization of all healthcare resources was obtained through consultation with a minimum of one pharmacist or one physician in each province. The number of healthcare practitioners interviewed in each province was three in British Columbia and Alberta, two in Québec, and one from Manitoba and Ontario. Nursing time was collected by one author (MP) through consultation with nurses in Québec who administer IV infusions, and these Québec estimates were further validated by physicians or pharmacists in the other provinces. Detailed interviews were conducted to obtain the personnel time, medical supplies, and infusion timeCitation9 required for treating mCRC patients with EGFR inhibitor and pre-medication () and patient follow-up and monitoring resources ().

Table 2. Resources involved in the preparation and administration of the medications.

Table 3. Patient follow-up and safety monitoring resources.

Personnel time, medication, and medical supplies costs required for the management of adverse events (AEs) due to EGFR inhibitor treatment were also obtained through consultation with pharmacists, physicians, and nurses (). Only the most frequently observed AEs (e.g., infusion reactions, grade 1 or 2 and grade 3 or 4 rash, and grade 3 or 4 hypomagnesemia) thought to be due to EGFR inhibitor treatment were included in the analysis. Incidence rates for each AE were obtained from the respective product monographs for panitumumab and cetuximab, and it was assumed that the AEs would occur in actual practice with the same incidence as reported in the product monographs. To be conservative, the treatment for severe (i.e., grade 3 or 4) infusion reactions was not included. Although the cost of severe infusion reactions is likely high (it has been estimated to be US$13,174 per episodeCitation10), the cost varies widely across patients, and reported incidences are rare and similar between the treatments (i.e., less than 1% with panitumumabCitation1 and 2% with cetuximabCitation5). For hypomagnesemia, because there is little data available reporting on the treatment duration with grade 3 or 4 cases, it was assumed that hypomagnesemia would occur 3 weeks after the first infusion of panitumumab or cetuximab treatment and patients would be treated with magnesium sulphate until the end of therapyCitation3,Citation11.

Table 4. Resources utilized in managing adverse events related to EGFRi treatment.

Unit costs for all healthcare resources identified in were obtained from a variety of sources. The resources used and their respective unit costs in each province are shown in .

Table 5. Canadian provincial health resource unit costs.

Sensitivity analyses were performed to test the impact of changing assumptions on the study outcome. The sensitivity analyses were: (1) the use of pre-medication and irinotecan with cetuximab was removed (including the associated pharmacist and nursing time and infusion supplies); (2) lower (1.5 m2) and higher (1.9 m2) average body surface area was assumed; (3) lower (65 kg) and higher (80 kg) average body weights were assumed; (4) only EGFRi (plus irinotecan) drug costs were considered (i.e., all drug preparation, drug administration, safety monitoring, and AE treatment costs were excluded); and (5) adverse event rates reported in the ASPECCT study were incorporated rather than the rates reported in the respective product monographs.

Results

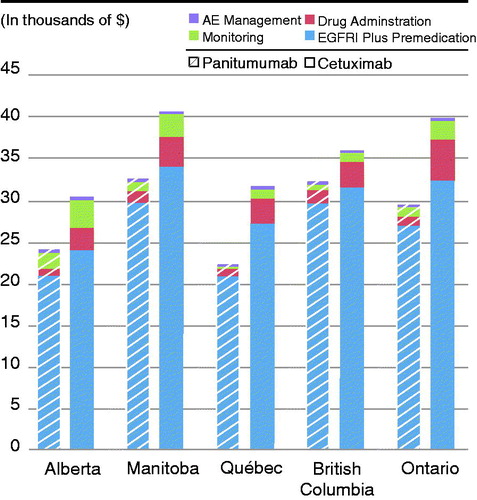

The total costs related to drug acquisition, medication preparation and administration, patient monitoring and follow-up, and treatment of AEs were substantially higher for cetuximab (with or without irinotecan) than for panitumumab in all provinces. Total costs for each cost category in provinces where cetuximab is used with or without irinotecan are shown in . The total annual per patient costs of panitumumab ranged from $22,203–$32,600, while the total annual per patient costs of cetuximab and cetuximab plus irinotecan treatment varied from $30,321–$40,908 and $36,081–$39,910, respectively ( and ). Per patient savings with panitumumab ranged from a low of $3815 in British Columbia to a high of $10,603 in Ontario.

Figure 1. Total per patient costs of managing mCRC with panitumumab vs cetuximab in Canadian provinces.

Table 6. Total per patient costs of managing mCRC with panitumumab vs cetuximab.

Table 7. Total per patient costs of managing mCRC with panitumumab vs cetuximab plus irinotecan.

In all provinces, the costs for EGFR inhibitor and pre-medication, professional time, medical supplies, infusion time, laboratory tests, and AE management are all lower with panitumumab than with cetuximab or cetuximab plus irinotecan.

The sensitivity analyses shown in and indicate that the analysis was robust and the results did not change when pre-medication costs or the costs related to drug preparation, drug administration, safety monitoring, and AE treatment were removed, or when assumptions regarding patients’ average body surface area and body weight were changed.

Table 8. Sensitivity analyses – Alberta, Manitoba, and Québec.

Table 9. Sensitivity analyses – British Columbia and Ontario.

Discussion

Total costs for the management of KRAS wild-type mCRC with EGFR inhibitor in patients who are chemorefractory were substantially higher with cetuximab monotherapy or cetuximab plus irinotecan than with panitumumab in all provinces studied. Per patient savings in each province were substantial and resulted in consistently lower costs for drug acquisition, medication preparation and administration, patient monitoring, and treatment of AEs with panitumumab compared with cetuximab. In sensitivity analyses where the use of pre-medication with cetuximab was removed, lower and higher average body weights and body surface areas were assumed, adverse event rates reported in the ASPECCT study were incorporated, and only the cost of EGFRi (plus irinotecan) was included, panitumumab remained cost saving in all scenarios in all provinces. The range of cost savings in each province were: $1614–$10,504 in Alberta, $1608–$14,308 in Manitoba, $4265–$13,825 in Québec, $150–$9815 in British Columbia, and $4393–$16,006 in Ontario.

The current study finding of a lower drug acquisition cost of EGFR inhibitor treatment with panitumumab was predicted based on the requirement for weekly dosing with cetuximab v every other week with panitumumab and where the cost per panitumumab dose is less than double the cost of each cetuximab infusion. Often, a lower drug acquisition cost poses a trade off against higher administration or monitoring costs. With panitumumab, this is not the case, even in British Columbia, where both EGFRi are dosed biweekly. Despite the equivalent dosing frequency, panitumumab was still cost saving in British Columbia, although the difference in cost between the EGFRi was smaller than in the provinces where cetuximab is still dosed weekly as per the approved labellingCitation2. As practice shifts in the other provinces to biweekly dosing of cetuximab, it is expected that the cost savings with panitumumab will be reduced but not entirely lost.

Although the finding of cost savings with panitumumab was consistent across the provinces, it should be pointed out that the total costs associated with the administration of both treatments varied significantly from one province to another. For example, the total patient costs for panitumumab in Québec were ∼30% less than in British Columbia and Manitoba.

Similarly, the cost of administration of cetuximab was 25% lower in Alberta than in the neighboring province of Manitoba. This result is not surprising in that each province runs its own Health Ministry with different cost structures and different standards of practice in terms of the delivery of healthcare. Even within a single province, the costs can vary across hospitals because each hospital establishes their own standards of care and manages their own budgets. In the case of the delivery of panitumumab and cetuximab, the primary reason for the difference in costs between the provinces lies in the number of infusions for each drug (as shown in ), where, in British Columbia and Manitoba, the total number of panitumumab infusions is 10, compared to only seven infusions in QC; similarly, the cost difference between Manitoba and Alberta for cetuximab is driven by the preference for 20 cetuximab infusions in Manitoba compared with 14 in Alberta.

To our knowledge, there have been no similar studies conducted in Canada. However, the results of the present study were similar to findings of a cost-minimization analysis conducted from the National Health Service perspective in GreeceCitation12, where the use of panitumumab was associated with cost savings of 12.4% to 17.7%. Song et al.Citation13 conducted a systematic review of the relative rates of infusion reactions associated with different treatments for mCRC along with the associated clinical and economic impact of the infusion reactions. They reported that all grade and grade 3–4 infusion reactions associated with cetuximab ranged from 7.6–33% and 0–22%, respectively. In contrast, rates of all grade and grade 3–4 infusion reactions associated with panitumumab ranged from 0–4% and 0–1%, respectively. The authors noted that the rates of IR for panitumumab appeared relatively consistent with rates observed in its clinical trials (as reported in the panitumumab product monograph), but that the rates seen with cetuximab varied widely across studies and acknowledged that many of the trials were smallCitation13. In their analysis of the cost of treatment in patients without and with infusion reactions, infusion reactions increased mean costs by $9308 where an emergency visit or hospitalization was required and by $1725 if treatment could be managed on an outpatient basis. The authors also concluded that infusion reactions can lead to treatment delays.

In a study conducted in the UK, Hoyle et al.Citation14 compared the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of panitumumab monotherapy and cetuximab (mono- or combination chemotherapy) and bevacizumab in combination with non-oxaliplatin chemotherapy for patients with KRAS WT metastatic colorectal cancer after first-line chemotherapy. The clinical analysis was based on a systematic review of the literature. For the economic comparison, a decision-analytic model was developed. In the economic evaluation, the base-case incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for KRAS WT patients compared with best supportive care was £98,000 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) for cetuximab, £88,000 per QALY for cetuximab plus irinotecan, and £150,000 per QALY for panitumumab. The authors of the paper concluded: ‘Although cetuximab and panitumumab appear to be clinically beneficial for KRAS WT patients compared with best supportive care, they are likely to represent poor value for money when judged by cost-effectiveness criteria currently used in the UK’(http://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/hta/volume-17/issue-14#abstract). While the UK and Canada have similar HTA processes and criteria, not to mention a similarity in healthcare systems, the decisions reached to reimburse products do not always coincide. It should be noted that, while the purpose of the study by Hoyle et al.Citation14 was to determine if the EGFRi are cost-effective and should be funded, the purpose of our study was to determine how the actual practice cost of the two EGFRi compare now that both are widely reimbursed in the third line setting.

Strengths of the current analysis include the fact that the costs were based on medication doses and treatment practices in use in Canada in several provinces. While an analysis conducted in one province may not always be generalizable to practice in another jurisdiction, the results of the comparison of panitumumab vs cetuximab in mCRC was consistent across the five provinces examined, despite differences in clinical practice and reimbursement guidelines. For this reason, the results are also expected to extend to the provinces not studied. In addition, the study also examined the cost differences between the two EGFRi according to shifting practice where cetuximab is now often dosed every 2 weeks rather than weekly (as is the case in British Columbia where cetuximab is used every other week in combination with irinotecan).

The study was somewhat limited in that the comparison between treatments was made based on health resource use and costs only and did not include a comparison of the treatments based on their relative efficacy or quality-of-life benefits. However, the ASPECCT studyCitation8 found that panitumumab and cetuximab similarly extended OS and resulted in similar rates of grade 3–4 adverse events. Therefore, with similar efficacy and safety/tolerability profiles, a comparison based on the costs of administering the products and following patient safety post-treatment is justified from the perspective of public drug plan decision-makers in Canada. In addition, because panitumumab and cetuximab are both reimbursed in the provinces studied in this NIA without qualification of how the treatments may differ in clinical effect or in whom a specific EGFR inhibitor should be used, the NIA comparison was felt to be relevant for physicians making decisions about which treatment to use.

A second limitation of the study stems from the fact that the health resource utilization information was collected according to expert opinion and was not validated through other methods such as chart review or prospective observation through a time-and-motion study. Third, payers and physicians in Canada may also be interested in a net impact analysis conducted from a societal perspective where patients’ and caregivers’ indirect costs related to lost time from work or other activities and/or out-of-pocket costs would be considered. However, because the resources utilized to deliver the EGFR inhibitors and monitor patients after their infusions differed so widely between the treatments, it was believed that the additional cost impact of patients’ out of pocket expenses and lost time from work or usual activities would not change the results in any meaningful way.

The findings of the study are important for hospitals in Canada because they show that considerable savings can be achieved across different budget items if an institution were to choose one EGFR inhibitor over another given the similar clinical outcomes. The analysis shows that, while the drug acquisition cost differences may be relatively minimal, the more intensive resource utilization in terms of personnel, medical supplies, laboratory tests, and infusion time make panitumumab a less costly option. Future research examining the real world clinical and economic outcomes associated with panitumumab and cetuximab may be of interest.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the study showed that the total health resource utilization costs related to the management of KRAS wild-type mCRC with EGFR inhibitor in patients for whom previous treatments have failed were higher with cetuximab monotherapy or cetuximab plus irinotecan than with panitumumab in the five Canadian provinces studied. While the findings of a lower drug acquisition cost of panitumumab could be predicted, the lower costs related to drug preparation and administration, patient safety monitoring, and management of AEs may not have been predicted. Given the consistency of the findings across the provinces, the results should be generalizable to other jurisdictions of Canada.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Medical writing support was funded by Amgen Canada.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

MP has conducted net impact analysis research for Amgen Canada Inc. LS has been a consultant for and participated in advisory boards for Amgen and made oral presentations sponsored by Amgen. PK, HL have participated on Amgen advisory boards.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Hagen Kennecke, British Columbia Cancer Agency for his assistance with the methodology of the study, and Dr Sharlene Gill, British Columbia Cancer Agency for her consultation and data access concerning practice in British Columbia. The authors also wish to thank Ms Lindy Forte for medical writing assistance.

References

- Amgen Canada Inc. Vectibix® (panitumumab) product monograph. August 31, 2015

- Bristol-Myers Squibb Canada. Erbitux® (cetuximab) product monograph. October 1, 2015

- Van Cutsem E, Peeters M, Siena S, et al. Open-label phase III trial of panitumumab plus best supportive care compared with best supportive care alone in patients with chemotherapy-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:1658-64

- Amado RG, Wolf M, Peeters M, et al. Wild-type KRAS is required for panitumumab efficacy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:1626-34

- Jonker DJ, O’Callaghan CJ, Karapetis CS, et al. Cetuximab for the treatment of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2007;357:2040-8

- Karapetis CS, Khambata-Ford S, Jonker DJ, et al. K-ras mutations and benefit from cetuximab in advanced colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1757-64

- Cunningham D, Humblet Y, Siena S, et al. Cetuximab Monotherapy and Cetuximab plus Irinotecan in Irinotecan-Refractory Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. N Engl J Med 2004;351:337-45

- Price T, Peeters M, Kim TW, et al. Panitumumab versus cetuximab in patients with chemotherapy-refractory wild-type KRAS exon 2 metastatic colorectal cancer (ASPECCT): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, non-inferiority phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:569-79

- Rapport Financier Annuel. Gouvernement du Québec, Ministère de la santé et des services sociaux. Formulaire AS-471. Quebec, Canada: Sante et Services sociaux Quebec; 2013

- Foley KA, Wang PF, Barber BL, et al. Clinical and economic impact of infusion reactions in patients with colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab. Ann Oncol 2010;21:1455-1461.

- Fakih M. Management of anti-EGFR-targeting monoclonal antibody-induced hypomagnesemia. Oncology (Williston Park) 2008;22:74-6

- Fragoulakis V, Papagiannopoulou V, Kourlaba G, et al. Cost-minimization analysis of the treatment of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer in Greece. Clin Ther 2012;34:2132-42

- Song X, Long SR, Barber B, et al. Systematic review on infusion reactions associated with chemotherapies and monoclonal antibodies for metastatic colorectal cancer. Curr Clin Pharmacol 2012;7:56-65

- Hoyle M, Crathorne L, Peters J, et al. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of cetuximab (mono- or combination chemotherapy), bevacizumab (combination with non-oxaliplatin chemotherapy) and panitumumab(monotherapy) for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer after first-line chemotherapy (review of technology appraisal No.150 and part review of technology appraisal No. 118): a systematic review and economic model. Health Technol Assess 2013;17:1-237