Abstract

Background:

Respiratory diseases exert a substantial burden on society, with newer drugs increasingly adding to the burden. Economic models are often used, but seldom reviewed.

Purpose:

To summarize economic models used in economic analyses of drugs treating moderate-to-severe/very severe asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Methods:

This study searched Medline and Embase from inception to the end of February 2015 for cost-effectiveness/utility analyses that examined at least one drug against placebo, another drug, or other standard therapy in asthma or COPD. Two reviewers independently searched and extracted data with differences adjudicated via consensus discussion. Data extracted included model used and its qualities, validation methods, treatments compared, disease severity, analytic perspective, time horizon, data collection (pro- or retrospective), input rates and sources, costs and sources, planned sensitivity analyses, criteria for cost-effectiveness, reported outcomes, and sponsor.

Results:

This study analyzed 53 articles; 14 (25%) on asthma and 39 (75%) COPD. Markov models were commonly used for both asthma and COPD-related economic evaluations. Relatively few studies validated their model. For asthma-related studies, 10 examined inhaled corticosteroids and nine studied omalizumab. Placebo or standard therapy was the comparison in 11 studies and active drugs in the remainder.

Conclusions:

Few studies include validation of their models. Furthermore, controversy concerning some results was uncovered in this study, which needs to be avoided in the future.

Keywords::

Introduction

Respiratory diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma are persistent, with little chance of complete remission. As well, both diseases are widespread, occurring throughout the world. The 2010 Global Burden of Disease study undertaken by the World Health Organization estimated that more than 9.6% of the world’s population have either COPD or asthma, affecting about 329 million and 334 million people, respectivelyCitation1.

Both COPD and asthma negatively impact patients in terms of health status, duration, and quality-of-life, as well as costsCitation2. These ailments also substantially impact society with respect to resource utilization (e.g., medical care, hospitalization, drugs and other treatments), and associated costs. A recent study from France estimated it cost €9382 (57% direct costs) for each patient with COPDCitation3. In the US, Ford et al.Citation4 predicted that the burden of COPD in that country would rise to $49 billion by 2020. O’Neill et al.Citation5 estimated that the cost of treating refractory asthma in the UK was between £2912 and £4217 per annum per patient. Thus, the costs are very large and increasing, which causes concern amongst payers and formulary managers.

Novel therapies are costly to develop. Estimates of the cost for the development and launching of a new drug run as high as USD $1.8 billionCitation6,Citation7. At the same time, success rates for new drugs have been declining and, thereby, returns on investment have been negatively impactedCitation6,Citation8. In order to recoup development expenses, the costs of developing novel therapeutics (both successful and unsuccessful) are usually passed onto the consumer. At the point of purchase, the consumer determines whether there is value for money in purchasing the novel therapeutics.

Consequently, there has been an emphasis on economics, which assesses value for moneyCitation9. Pharmacoeconomic analyses apply the concepts of economics to the comparison of drugsCitation10. Interest in this area is high, as evidenced by recent reviews of the pharmacoeconomics of both asthmaCitation11,Citation12 and COPDCitation13. However, these reviews have focused mainly on either the results of the analysesCitation11 or the quality of the reportingCitation12,Citation14. A review focusing on the models used to arrive at the pharmacoeconomic outcomes has not been undertaken to date.

There are three basic models for assessing the pharmacoeconomics of drugs; prospective, predictive and retrospectiveCitation15. Prospective models are often associated with clinical trials comparing drugs or treatments, which allows the prospective gathering of data. The predictive model is usually referred to as a decision analytic analysis, but also includes Markov models and discrete event simulations. These types predict the average outcome, given a set of inputs. The retrospective model uses patient charts or databases, using data that have already been collected. In general, prospective models focus on short-term acute treatments and usually cannot be extrapolated to long-term therapyCitation15.

Despite reviews of the economics of drugs in asthma or COPD, the models used have seldom been their focus, as evidenced by a search of the literature. While there was one recent review identified by KirschCitation13 that examined only Markov models in COPD, that study reviewed only smoking cessation interventions, rather than drugs to treat asthma or COPD. We, therefore, undertook the present research to review the types of models that have been utilized in cost-effectiveness analyses of drugs used to treat asthma and COPD since the introduction of biologic treatment.

Methods

This research was guided by the PRISMA statement for reviewsCitation16. Criteria for acceptable studies were developed a priori, as was the search strategy. All steps of the process were done in duplicate by independent reviewers.

Eligibility criteria

Studies eligible for inclusion in this study were economic evaluations related to pharmacotherapy interventions for at least moderate-to-severe asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or both. The target population consisted of patients having severe disease (or worse); however, patient samples often presented mixed severities. We, therefore, allowed patients having moderate-to-severe disease or perhaps a small proportion with milder forms. For this analysis, only the severity of the disease itself was considered; treatments exclusively used for acute exacerbations, whether severe or not, were not accepted. Asthma was considered sufficiently severe if identified as such by the authors or if patients were symptomatic on >800 µg/day of corticosteroids or if their average peak expiratory volume (PEV) was <70% (i.e., below the midpoint of the range for the moderate disease). COPD was considered sufficiently severe if the majority of patients were classified as having GOLD-3 or GOLD-4 disease or if the average forced expiratory volume (FEV) was <65% (i.e., below the midpoint of the range for moderate disease). We accepted studies dealing with either adults or pediatrics. Patients could not be immunocompromised or have any other concomitant respiratory diseases. Either inpatient or outpatient populations or both could be examined. We also accepted dynamic progression models of COPD that included disease severity that ranged from mild-to-severe or very severe disease as well as death, such as Markov models or discrete event simulations.

There must have been two or more therapeutic options compared, at least one of which was a drug. Acceptable types of analyses were those that combined both costs and outcomes into an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). That is, we included cost-effectiveness and cost-utility analyses, but excluded cost-minimization and cost-consequence analyses.

The first biologic to be licensed (for any indication) was infliximab, in 1998Citation17. Its original indication was Crohn’s disease, but the potential for using biologics in treating respiratory diseases was quickly recognizedCitation18. Trials were soon undertaken in patients with COPDCitation19. It may be postulated that the era of biologic treatment for asthma began with the Australian approval of omalizumab in 2002Citation1 Citation7. However, the process began in the year 2000Citation20. The authors assumed that economic analyses of biologic treatment related to asthma would not have been published prior to the year 2000. As such, only full text, peer-reviewed articles published between 2000–2015 were considered.

Information sources

The search engines used to identify relevant articles were: Embase 1980–2015 week 7, and Medline 1946 to February week 2, 2015. Within these databases, searches were limited to the above-mentioned dates. Retrieved articles were hand searched for relevant studies not identified by search engines. Furthermore, PubMed was searched for more recent studies not yet included in the other search engines used.

Search and study selection

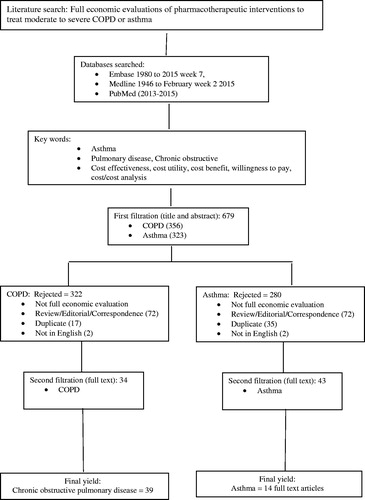

Two reviewers independently searched the databases using key words ‘cost effectiveness.mp OR exp cost-benefit analysis’, ‘costs and cost analysis OR cost utility.mp’, ‘willingness to pay.mp’, ‘asthma OR COPD’, and ‘full text’. Results were compared first after examining the titles and abstracts (first filtration) and again after retrieving full text articles (second filtration). At each stage, discrepancies were adjudicated via consensus discussion.

Data items

Data collected included author names, year of publication, country, sponsor, model type and structure, validation of the model, disease and its severity, patients examined, data collection (i.e., prospective vs retrospective), treatments compared, time horizon(s), analytic perspective(s), clinical rates used and their sources, resources costed and sources of utilization rates, currency and year of costing, discount rate for costs and outcomes, criterion used to determine cost-effectiveness, outcomes examined, sensitivity analyses planned, reported costs for each treatment, reported outcomes, incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs), sensitivity analyses reported, and conclusions made by the authors. Items were recorded in a spreadsheet and results were then compared between data extractors. All cases of difference were settled though discussion.

Data analysis

Models were defined in three broad categories: trial based (prospective), decision models (predictive), and models based on patient data records (retrospective). Three types of trial models were possible, including (1) the dedicated economic RCT which was designed specifically for an economic analysis, (2) the piggyback trial, where an economic arm was added to the clinical protocol of the RCT and all data were collected prospectively, and (3) the retrospective RCT, where an existing RCT was used and economic data were fitted post-hoc. Four types of decision models were considered. They included (1) the classical decision tree, (2) the Markov model (and all of its variants), (3) patient level simulations (e.g., discrete event simulations), and (4) spreadsheet models where calculations were done on a spreadsheet as opposed to dedicated software-based models. Finally, patient data based models comprised three types: (1) administrative databases, which were designed for other purposes such as the payment of claims for healthcare services, (2) patient registries designed to prospectively collect patient data for specific diseases, and (3) patient charts, which could be either paper or electronic. Data were tabulated and analyzed descriptively.

Results

The search process is depicted in . We were able to use data from 53 articles, including 14 (25%) in patients with asthmaCitation12,Citation21–33 and 39 (75%) in patients with COPDCitation33–71. No papers were found that examined patients having both diseases concomitantly.

Among the 14 papers on asthma, eight were from Europe, five (36%) from North America, and one (7%) from South America. Nine (64%) were sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry, two (14%) by non-government foundations, and three (21%) did not mention funding. summarizes the models that have been used. In asthma patients, one was trial based (retrospectively modeled an existing RCT), 11 were decision models (10 Markov and one spreadsheet decision analysis), and two were based on electronic patient data records.

Table 1. Models used in economic analyses of severe asthma and COPD.

provides details of the models, describing their structures and characteristics. Among the Markov models used in asthma, only three reported validation of some sort, but most often providing few details. All of the studies collected data retrospectively. Ten of the studies examined inhaled corticosteroids and nine studies omalizumab. Placebo or standard therapy was the comparison in 11 studies and active drugs in the remainder. Six focused on adults only, seven included adolescents as well as adults, and one was restricted to children <18. The perspective of the analysis was societal in three, the healthcare system in nine, and third party payer in two. Two studies used a time horizon of 12 weeks, seven used 1 year, one used 10 years and six examined over a lifetime. Two studies employed two different time horizons.

Table 2. Model structure and characteristics in economic analyses of severe asthma.

summarizes the inputs into the models and their sources for asthma-related pharmacoeconomic studies. Eleven studies used RCTs as their primary source for clinical data and three used patient data. In seven analyses, discounting was not done because the time horizon did not exceed 1 year. In all of the others, discounting was done for both costs and outcomes. Cost were discounted from 3–5% and outcomes from 1–3.5%. Ten included only direct costs and four included both direct and indirect costs. Ten out of 12 reported sensitivity analyses, and two did not perform any.

Table 3. Model inputs in economic analyses of severe asthma.

Results of the models used in the economic analysis of drugs used for severe asthma appear in . Costs were reported in either US dollars, Canadian dollars, British pounds or Euros. Results varied widely; for example Brown et al.Citation21 and Dal Negro et al.Citation113 concluded that omalizumab compared to standard care was cost-effective, while Campbell et al.Citation22 reported that omalizumab was not cost-effective compared to standard care.

Table 4. Model outputs from economic analyses of severe asthma.

There were 39 studies that employed economic models to assess drugs used in severe COPD. describes model characteristics in economic analysis of severe COPD. Economic analyses were carried out in Australia (1), Belgium (3), Canada (7), Denmark (1), Finland (1), Germany (1), Greece (1), Italy (1), the Netherlands (3), Norway (1), Singapore (1), Spain (1), Sweden (3), Switzerland (1), the UK (9), and the US (7). Most of the studies (30/39, 77%) were sponsored by pharmaceutical companies. The remainder of the studies did not explicitly state source of funding, but did not include authors who were affiliated with either a pharmaceutical or contract research firm. Approximately half of the articles (19/39, 49%) did not mention any validation process. The shortest time period used to analyze data was 16 weeks and the longest was a lifetime. Thirteen of the 39 studies used a time horizon of between 3–5 years, and 10 used a time horizon of 1 year. Few studies (five) approached their analysis from a societal perspective, while most used a third party payer perspective. Most studies (67%) collected data retrospectively, with 13 of the 39 (33%) studies collecting data prospectively. A Markov structured model was used in 19 studies. There were eight studies that were based on randomized controlled trials.

Table 5. Model structure and characteristics in economic analyses of severe COPD.

details the inputs into economic models in severe COPD. Most (29/39, 74%) studies calculated direct costs only. Where applicable (i.e., in studies where the time horizon was more than 1 year), costs and outcomes were discounted between 3–5%, depending on local pharmacoeconomic requirements. Willingness-to-pay thresholds used for interpretation of results varied widely, between £20,000/QALY and $100,000/QALY.

Table 6. Model inputs in economic analyses of severe COPD.

presents the results from the economic models used in severe COPD. Agents or comparators used in analysis include: aclidimium, betamethasone, fluticasone propionate, formeterol, indacaterol, indacaterol/glyopyrronium, ipratroprium, long-acting beta-agonists, OM-85 BV (immunostimulating agent), placebo, roflumilast, salmeterol, tiotropium, and usual care.

Table 7. Model outputs from economic analyses of severe COPD.

Discussion

In this review, we were able to use data from 14 studies that examined patients with asthma and 39 that researched patients with COPD. Our search did not find studies that examined patients who suffered from both asthma and COPD simultaneously. Furthermore, with the exception of a few studies, our search did not locate studies that took into account the severity of the diseases. One reason could be the difficulty in defining the different levels of severity. Furthermore, few drugs are expressly indicated for severe cases of either COPD or asthma and, as such, economic evaluations with this perspective have not been undertaken.

In both asthma and COPD-related economic evaluations, predictive decision-analytic type models were predominant, with Markov models being most commonly used. Given the chronic nature of either asthma or COPD, use of Markov and discrete event simulation models may be most appropriate.

However, study parameters, for the most part, were not validated. Validation of models may include face validation, where experts would confirm the model structure used, data sources cited, and assumptions made. Other types of validation such as internal, external, or predictive validity were also largely absent from the studies included in this review. The joint task force of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) and the Society for Medical Decision Making (SMDM) recommend use of validation in their Good Practices Research reportCitation34.

Specifically, only Norman et al.Citation12 (who focused on asthma) discussed validation of their model in detail. They did extensive testing to assure the model integrity and that it generated accurate results. Some authors used existing published models, assuming that validation had been done; however, in many cases, the original publications did not discuss validation. For example, van Nooten et al.Citation32 indicated that they used ‘the validated and published Markov 5-state omalizumab model’, citing Brown et al.Citation21 and Dewilde et al.Citation25 (the original publication) as references. However, neither the word ‘validate’ nor ‘validation’ appears in the paper by Dewilde et al. Since there is overlap in the authorship of those three papers, they would presumably have had access to that information, but failed to include it in their articles. Therefore, there is a need for authors to describe their validation process explicitly and completely.

On the other hand, Hoogedorn et al.Citation163 identified seven studies and requested that these authors validate their own models using pre-identified criteria. They found a general consistency in structure across models. Outcomes varied somewhat, but the variation could be explained by differences in input values for disease progression and mortality. There was a high probability (90–100% for five models, 70% and 50% for the others) of lifetime cost-effectiveness at a willingness-to-pay of €50,000/QALY. Note that this threshold is quite high compared to those in many jurisdictions. Those authors concluded that mortality was the important factor in determining differences between ICERs.

We identified at least three studiesCitation35–37 that did not analyze and present their findings according to well-accepted standard proceduresCitation37,Citation38. For example, Dal Negro et al.Citation35 compared each drug to placebo, which is not appropriate when some alternatives are dominated. According to Drummond et al.Citation38, all dominated drugs must first be eliminated from consideration in the analysis and non-dominated alternatives analyzed incrementally, starting with the choice having the lowest cost. Reporting results that include dominated alternatives may affect what is considered to be within accepted threshold parameters. In their analyses, Dal Negro et al. failed to eliminate the placebo and fluticasone arms, which were strongly dominated, as well as formoterol/budesonide, which was extendedly dominated. Nevertheless, in the final analysis, their drug was still cost-effective. Earnshaw et al.Citation36 also compared each drug to placebo, reporting an ICER for fluticasone/salmeterol vs placebo of $33,865 per additional QALY gained for which they claimed cost-effectiveness, citing a threshold of $50,000. However, when calculating incrementally from salmeterol (next in line), the ICER would be ∼$69,889, which far exceeds their limit for cost-effectiveness. A similar situation occurs with the study by ObaCitation37. In his , he recognized that two drugs were ‘dominated through extended dominance’. Therefore, they should both have been eliminated, but, despite that, Oba calculated an incremental ICER for fluticasone/salmeterol, comparing it with fluticasone alone (a dominated choice). The reported (incremental) ICER was $41,092; however, had it been properly compared with the only non-dominated choice (i.e., placebo), the ICER would have been ∼$52,046. If the same criterion used by Earnshaw et al. had been used to judge this result (i.e., $50,000/QALY gained), it would also fail to achieve cost-effectiveness. Thus, there is an apparent need for appropriate reporting of results from economic models.

Conclusions

We have summarized the economic analyses that examined drug use in severe asthma and COPD. Very few biologic drugs have been studied in these patients, and more options are needed. In asthma-related studies, there was not a large number that were found to be cost-effective, and often at a quite high level of willingness-to-pay. Controversy concerning some results was uncovered in this study, which needs to be avoided in the future. More research is needed to fill gaps in knowledge.

As well, there is a need for more complete and accurate reporting of results. The authors should be required to address the issue of model validation and provide adequate documentation of how it was done. Insufficient attention has been placed on the calculation and presentation of results when there are multiple options being compared. Authors, reviewers, and editors need to assure that manuscripts adhere to guidelines for reporting results.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Janssen Pharmaceutica.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

TRE has received sponsorship from Janssen Pharmaceutica and has declared consultancy/advisory interests from Janssen-Cilag. JVL is an employee of Janssen Pharmaceutica NV and MEHH was an employee at the time of writing. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

This review was funded by Janssen-Cilag BV Drs. Einarson and Bereza received financial consultation for this research and manuscript At the time of writing, Nielsen, Van Laer, and Hemels were all employees of Janssen.

References

- Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:163-96

- Srivastava K, Thakur D, Sharma S, et al. Systematic review of humanistic and economic burden of symptomatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PharmacoEconomics 2015;33:467-88

- Laurendeau C, Chouaid C, Roche N, et al. [Management and costs of chronic pulmonary obstructive disease in France in 2011.]. Rev Mal Respir 2015;32:682-91

- Ford ES, Murphy LB, Khavjou O, et al. Total and state-specific medical and absenteeism costs of COPD among adults aged ≥18 years in the United States for 2010 and projections through 2020. Chest 2015;147:31-45.

- O'Neill S, Sweeney J, Patterson CC, et al. The cost of treating severe refractory asthma in the UK: an economic analysis from the British Thoracic Society Difficult Asthma Registry. Thorax 2014;70:376–8

- Mestre-Ferrandiz J, Sussex J, Towse A. The R&D cost of a new medicine. London: University College, 2012

- Paul SM, Mytelka DS, Dunwiddie CT, et al. How to improve R&D productivity: the pharmaceutical industry’s grand challenge. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2010;9:203-14

- Berndt ER, Nass D, Kleinrock M, et al. Decline in economic returns from new drugs raises questions about sustaining innovations. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34:245-5.

- Starkie HJ, Briggs AH, Chambers MG. Pharmacoeconomics in COPD: lessons for the future. Int J COPD 2008;3:71-88

- Health care cost quality and outcomes. In: Berger ML, Bingefors K, Hedbloom E, et al., eds. Lawrenceville, NJ: ISPOR lexicon. Lawrenceville, NJ: ISPOR, 2003

- Domínguez-Ortega J, Phillips-Anglés E, Barranco P, et al. Cost-effectiveness of asthma therapy: a comprehensive review. J Asthma 2014;24:1-23

- Norman G, Faria R, Paton F, et al. Omalizumab for the treatment of severe persistent allergic asthma: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2013;17:1-342

- Kirsch F. A systematic review of quality and cost-effectiveness derived from Markov models evaluating smoking cessation interventions in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2015;15:301-16

- Campbell JD, Spackman DE, Sullivan SD. Health economics of asthma: assessing the value of asthma interventions. Allergy 2008;63:1581-92

- Einarson TR, Shear NH, Oh PI. Models for pharmacoeconomic analysis. Can J Clin Pharmacol 1997;4:25-9

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097

- FDA Department of Health and Human Services. Reference number 98-0012. Infliximab approval. Silver Spring, MD, USA, 1998. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsareDevelopedandApproved/ApprovalApplications/TherapeuticBiologicApplications/ucm107700.pdf. Accessed July 2015

- Li L, Das AM, Torphy TJ, et al. What's in the pipeline? Prospects for monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) as therapies for lung diseases. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2002;15:409-16

- van der Vaart H, Koëter GH, Postma DS, et al. First study of infliximab treatment in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;172:465-9

- FDA Department of Health and Human Services. BLA STN 103976/0. Review of clinical safety data: original BLA submitted on June 2 2000. Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2000. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsareDevelopedandApproved/ApprovalApplications/TherapeuticBiologicApplications/ucm113458.pdf. Accessed July 2015

- Brown R, Turk F, Dale P, et al. Cost-effectiveness of omalizumab in patients with severe persistent allergic asthma. Allergy 2007;62:149-53

- Campbell JD, Spackman DE, Sullivan SD. The costs and consequences of omalizumab in uncontrolled asthma from a USA payer perspective. Allergy 2010;65:1141-8

- Dal Negro RW, Pradelli L, Tognella S, et al. Cost-utility of add-on omalizumab in difficult-to-treat allergic asthma in Italy. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;43:45-53

- Dal Negro RW, Tognella S, Pradelli L. A 36-month study on the cost/utility of add-on omalizumab in persistent difficult-to-treat atopic asthma in Italy. J Asthma 2012;49:843-8

- Dewilde S, Turk F, Tambour M, et al. The economic value of anti-IgE in severe persistent, IgE-mediated (allergic) asthma patients: adaptation of INNOVATE to Sweden. Curr Med Res Opin 2006;22:1765-76

- Gerzeli S, Rognoni C, Quaglini S, et al. Cost-effectiveness and cost-utility of beclomethasone/formoterol versus fluticasone propionate/salmeterol in patients with moderate to severe asthma. Clin Drug Invest 2012;32:253-65

- Miller E, Sears MR, McIvor A, et al. Canadian economic evaluation of budesonide-formoterol as maintenance and reliever treatment in patients with moderate to severe asthma. Can Respir J 2007;14:269-7.

- Single technology appraisal (STA). Manufacturer submission of evidence. Camberley, UK: Novartis Pharmaceuticals presentation to NICE, 2007. www.nice.org/nicemedia/live/11686/37589/37589.pdf. Accessed July 2015

- Oba Y, Salzman GA. Cost-effectiveness analysis of omalizumab in adults and adolescents with moderate-to-severe allergic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004;114:265-9

- Rodríguez-Martínez CE, Sossa-Briceño MP, Castro-Rodriguez JA. Cost-utility analysis of the inhaled steroids available in a developing country for the management of pediatric patients with persistent asthma. J Asthma 2013;50:410-18

- Price MJ, Briggs AH. Development of an economic model to assess the cost effectiveness of asthma management strategies. PharmacoEconomics 2002;20:183-94

- van Nooten F, Stern S, Braunstahl GJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness of omalizumab for uncontrolled allergic asthma in the Netherlands. J Med Econ 2013;16:342-8

- Wu AC, Paltiel AD, Kuntz KM, et al. Cost-effectiveness of omalizumab in adults with severe asthma: results from the Asthma Policy Model. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;120:1146-52

- Caro JJ, Briggs AH, Siebert U, et al. Modeling good research practices–overview: a report of the ISPOR-SMDM Modeling Good Research Practices Task Force-1. Med Decis Making 2012;32:667-77

- Dal Negro RW, Eandi M, Pradelli L, et al. Cost-effectiveness and healthcare budget impact in Italy of inhaled corticosteroids and bronchodilators for severe and very severe COPD patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2007;2:169-76

- Earnshaw SR, Wilson MR, Dalal AA, et al. Cost-effectiveness of fluticasone propionate/salmeterol (500/50 microg) in the treatment of COPD. Respir Med 2009;103:12-21

- Oba Y. Cost-effectiveness of salmeterol, fluticasone, and combination therapy for COPD. Am J Manag Care 2009;15:226-32

- Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, et al. Methods for the evaluation of health care programmes. 3rd edn. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2006

- Ayres JG, Higgins B, Chilvers ER, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of anti-immunoglobulin E therapy with omalizumab in patients with poorly controlled (moderate-to-severe) allergic asthma. Allergy 2004;59:701-8

- Humbert M, Beasley R, Ayres J, et al. Benefits of omalizumab as add-on therapy in patients with severe persistent asthma who are inadequately controlled despite best available therapy (GINA 2002 step 4 treatment): INNOVATE. Allergy 2005;60:309-16

- Price D, Brown RE, Lloyd A. Burden of poorly controlled asthma for patients and society in the UK. Prim Care Respir J 2004;13:113

- Lowhagen O, Ekstrom L, Holmberg S, et al. Experience of an emergency mobile asthma treatment programme. Resuscitation 1997;35:243-7

- Statistics Canada. Complete life tables, Ontario, 1995–1997. Secondary complete life tables, Ontario, Ottawa, Ontario, CANADA, 1995–1997. 2007

- Bousquet J, Cabrera P, Berkman N, et al. The effect of treatment with omalizumab, an anti-IgE antibody, on asthma exacerbations and emergency medical visits in patients with severe persistent asthma. Allergy 2005;60:302-8

- Ayres JG, Price MJ, Efthimiou J. Cost-effectiveness of fluticasone propionate in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a double-blind randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Respir Med 2003;R97:212-20

- Tsuchiya A, Brazier J, McColl E, Parkin D. Deriving p[reference-based single indices from non-preference based condition-specific instruments: converting AQLQ into EQ-5D indices. Heath Economics Group Discussion Paper Series 02/01. Sheffield, UK: University of Sheffield School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR), Whiterose, University Consortium, Sheffield UK, May 2002

- Sullivan SD, Buxton M, Andersson LF, et al. Costeffectiveness analysis of early intervention with budesonide in mild persistent asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003;112:1229-36

- Garattini L, Catelnuovo E, Lanzeni D, et al. Durata e costo delle visite in medicina generale: il progetto DYSCO. Farmacoeconomia e Percorsi Terapeutici 2003;4:109-14

- Papi A, Paggiaro P, Nicolini G. ICAT SE study group. Beclomethasone/formoterol vs fluticasone/salmeterol inhaled combination in moderate to severe asthma. Allergy 2007;62:1182-8

- Samyshkin Y, Kotchie RW, Mörk AC, et al. Cost-effectiveness of roflumilast as an add-on treatment to long-acting bronchodilators in the treatment of COPD associated with chronic bronchitis in the United Kingdom. Eur J Health Econ 2014;15:69-82

- De Marco R, Locatelli F, Cazzoletti L. Incidence of asthma and mortality in a cohort of young adults: a 7-year prospective study. Respir Res 2005;16:6-95

- Vogelmeier C, D’Urzo A, Pauwels R. Budesonide/formoterol maintenance and reliever therapy: an effective asthma treatment option? Eur Respir J 2005;26:819-28

- Lanier B, Marshall GDJ. Unanswered questions on omalizumab (Xolair) patient selection and follow-up. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2004;92:198-200

- Lloyd A, Price D, Brown R. The impact of asthma exacerbations on health-related quality of life in moderate to severe asthma patients in the UK. Prim Care Respir J 2007;16:22-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.3132/pcrj.2007.00002. Accessed July 2015

- de Vries F, Setakis E, Zhang B, et al. Long-acting beta2-agonists in adult asthma and the pattern of risk of death and severe asthma outcomes: a study using the GPRD. Eur Respir J 2010;36:494-502. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.0124209. Accessed July 2015

- Busse W, Corren J, Lanier BQ, et al. Omalizumab, anti-IgE recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of severe allergic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001;108:184-90

- Soler M, Matz J, Townley R, et al. The anti-IgE antibody omalizumab reduces exacerbations and steroid requirement in allergic asthmatics. Eur Respir J 2001;18:254-61

- Kavuru M, Melamed J, Gross G. Salmeterol and fluticasone propionate combined in a new powder inhalation device for the treatment of asthma: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2000;105:1108-16

- Hoskins G, Smith B, Thomson C. The cost implications of an asthma attack. Pediatr Asthma Allergy Immunol 1998;12:193-8

- Paltiel AD, Fuhlbrigge AL, Fitch BT, et al. Cost-effectiveness of inhaled corticosteroids in adults with mildto- moderate asthma: results from the asthma policy model. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001;108:39-46

- Walker S, Monteil M, Phelan K, et al. Anti-IgE for chronic asthma in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(3):CD003559

- Corren J, Casale T, Deniz Y, et al. Omalizumab, a recombinant humanized anti-IgE antibody, reduces asthma-related emergency room visits and hospitalizations in patients with allergic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003;111:87-90

- Niebauer K, Dewilde S, Fox-Rushby J, et al. Impact of omalizumab on quality-of-life outcomes in patients with moderate-to-severe allergic asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2006;96:316-26

- Burge PS, Calverley PM, Jones PW, et al. Randomised, double blind, placebo controlled study of fluticasone propionate in patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the ISOLDE trial. BMJ 2000;320:1297-303

- Briggs AH, Lozano-Ortega G, Spencer S, et al. Estimating the cost-effectiveness of fluticasone propionate for treating chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the presence of missing data. Value Health 2006;9:227-35

- Briggs AH, Glick HA, Lozano-Ortega G, et al. Is treatment with ICS and LABA cost-effective for COPD? Multinational economic analysis of the TORCH study. Eur Respir J 2010;35:532-9

- Calverley PM, Anderson JA, Celli B, et al. Salmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2007;356:775-89

- Chuck A, Jacobs P, Mayers I, et al. Cost-effectiveness of combination therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Can Respir J 2008;15:437-43

- Collet JP, Ducruet T, Haider S, et al. Economic impact of using an immunostimulating agent to prevent severe acute exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Can Respir J 2001;8:27-33

- Dalal AA, St Charles M, Petersen HV, et al. Cost-effectiveness of combination fluticasone propionate-salmeterol 250/50 microg versus salmeterol in severe COPD patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2010;9:179-87

- Gani R, Griffin J, Kelly S, et al. Economic analyses comparing tiotropium with ipratropium or salmeterol in UK patients with COPD. Prim Care Respir J 2010;19:68-74

- Oostenbrink JB, Rutten-van Mölken MPMH, Monz BU. Probabilistic Markov model to assess the cost-effectiveness of bronchodilator therapy in COPD patients in different countries. Value Health 2005;8:32-46 http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.524-4733.2005.03086.x. Accessed July 2015

- Hettle R, Wouters H, Ayres J, et al. Cost-utility analysis of tiotropium versus usual care in patients with COPD in the UK and Belgium. Respir Med 2012;106:1722-33

- Oostenbrink JB, Al MJ, Oppe M, et al. Expected value of perfect information: an empirical example of reducing decision uncertainty by conducting additional research. Value Health 2008;11:1070-80

- Hogan TJ, Geddes R, Gonzalez ER. An economic assessment of inhaled formoterol dry powder versus ipratropium bromide pressurized metered dose inhaler in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Ther 2003;25:285-97

- Hoogendoorn M, Al MJ, Beeh KM, et al. Cost-effectiveness of tiotropium versus salmeterol: the POET-COPD trial. Eur Respir J 2013;41:556-64

- Jones PW, Wilson K, Sondhi S. Cost-effectiveness of salmeterol in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an economic evaluation. Respir Med 2003;97:20-6

- Karabis A, Mocarski M, Eijgelshoven I, et al. Economic evaluation of aclidinium bromide in the management of moderate to severe COPD: an analysis over 5 years. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res 2014;5:175-85

- Lee KH, Phua J, Lim TK. Evaluating the pharmacoeconomic effect of adding tiotropium bromide to the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in Singapore. Respir Med 2006;100:2190-6

- Lofdahl CG, Ericsson A, Svensson K, et al. Cost effectiveness of budesonide/formoterol in a single inhaler for COPD compared with each monocomponent used alone. PharmacoEconomics 2005;23:365-75

- Maniadakis N, Tzanakis N, Fragoulakis V, et al. Economic evaluation of tiotropium and salmeterol in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in Greece. Curr Med Res Opin 2006;22:1599-607

- Mittmann N, Hernandez P, Mellström C, et al. Cost effectiveness of budesonide/formoterol added to tiotropium bromide versus placebo added to tiotropium bromide in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Australian, Canadian and Swedish healthcare perspectives. PharmacoEconomics 2011;29:403-14

- Naik S, Kamal KM, Keys PA, et al. Evaluating the cost-effectiveness of tiotropium versus salmeterol in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res 2010;2:25-36

- Najafzadeh M, Marra CA, Sadatsafavi M, et al. Cost effectiveness of therapy with combinations of long acting bronchodilators and inhaled steroids for treatment of COPD. Thorax 2008;63:962-7

- Neyt M, Devriese S, Thiry N, et al. Tiotropium's cost-effectiveness for the treatment of COPD: a cost-utility analysis under real-world conditions. BMC Pulm Med 2010;10:47. doi: 10.1186/471-2466-10-47.

- Nielsen R, Kankaanranta H, Bjermer L, et al. Cost effectiveness of adding budesonide/formoterol to tiotropium in COPD in four Nordic countries. Respir Med 2013;107:1709-21

- Oba Y. Cost-effectiveness of long-acting bronchodilators for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Mayo Clin Proc 2007;82:575-82

- Ferguson GT, Anzueto A, Fei R, et al. Effect of fluticasone propionate/salmeterol (250/50 microg) or salmeterol (50 microg) on COPD exacerbations. Respir Med 2008;102:1099-108

- Onukwugha E, Mullins CD, DeLisle S. Using cost-effectiveness analysis to sharpen formulary decision-making: the example of tiotropium at the Veterans Affairs health care system. Value Health 2008;11:980-8

- Oostenbrink JB, Rutten-van Mölken MP, Al MJ, et al. One-year cost-effectiveness of tiotropium versus ipratropium to treat chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J 2004;23:241-9

- Vincken W, van Noord JA, Greefhorst AP. Improved health outcomes in patients with COPD during 1 year9s treatment with tiotropium. Eur Respir J 2002;19:209-16

- Oostenbrink JB, Rutten-van Mölken MP, Monz BU, et al. Probabilistic Markov model to assess the cost-effectiveness of bronchodilator therapy in COPD patients in different countries. Value Health 2005;8:32-46

- Price D, Gray A, Gale R, et al. Cost-utility analysis of indacaterol in Germany: a once-daily maintenance bronchodilator for patients with COPD. Respir Med 2011;105:1635-47

- Price D, Asukai Y, Ananthapavan J, et al. A UK-based cost-utility analysis of indacaterol, a once-daily maintenance bronchodilator for patients with COPD, using real world evidence on resource use. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2013;11:259-74

- Price D, Keininger D, Costa-Scharplatz M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of the LABA/LAMA dual bronchodilator indacaterol/glycopyrronium in a Swedish healthcare setting. Respir Med 2014;108:1786-93

- Asukai Y, Baldwin M, Fonseca T, et al. Improving clinical reality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease economic modelling: development and validation of a micro-simulation approach. PharmacoEconomics 2013;31:151-61

- Rutten-van Mölken MP, Oostenbrink JB, Miravitlles M, et al. Modelling the 5-year cost effectiveness of tiotropium, salmeterol and ipratropium for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Spain. Eur J Health Econ 2007;8:123-35

- Rutten-van Mölken MP, van Nooten FE, Lindemann M, et al. A 1-year prospective cost-effectiveness analysis of roflumilast for the treatment of patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pharmacoeconomics 2007;25:695-711

- Samyshkin Y, Schlunegger M, Haefliger S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of roflumilast in combination with bronchodilator therapies in patients with severe and very severe COPD in Switzerland. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2013;8:79-87

- Sin DD, Golmohammadi K, Jacobs P. Cost-effectiveness of inhaled corticosteroids for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease according to disease severity. Am J Med 2004;116:325-31

- Spencer M, Briggs AH, Grossman RF, et al. Development of an economic model to assess the cost effectiveness of treatment interventions for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PharmacoEconomics 2005;23:619-37

- Van Der Palen J, Monninkhof E, Van Der Valk P, et al. Cost effectiveness of inhaled steroid withdrawal in outpatients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 2006;61:29-33

- Dolan P. Modeling valuations for EuroQol health states. Med Care 1997;35:1095-108

- Borg S, Ericsson A, Wedzicha J, et al. A computer simulation model of the natural history and economic impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Value Health 2004;7:153-67

- Collet JP, Shapiro P, Ernst P, et al. Effects of an immunostimulating agent on acute exacerbations and hospitalizations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The PARI-IS Study Steering Committee and Research Group. Prevention of Acute Respiratory Infection by an Immunostimulant. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997;156:1719-24

- Anzueto A, Ferguson GT, Feldman G, et al. Effect of fluticasone propionate/salmeterol (250/50) on COPD exacerbations and impact on patient outcomes. COPD 2009;6:320-9

- Stanford RH, Shen Y, McLaughlin T. Cost of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the emergency department and hospital: an analysis of administrative data from 218 US hospitals. Treat Respir Med 2006;5:343-9

- Nurmagambetov T, Atherly A, Williams S, et al. What is the cost to employers of direct medical care for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? COPD 2006;3:203-9

- Calverley PM, Boonsawat W, Cseke Z, et al. Maintenance therapy with budesonide and formoterol in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J 2003;22:912-19

- Calverley P, Pauwels R, Vestbo J, et al. TRial of Inhaled STeroids ANd long-acting beta2 agonists study group. Combined salmeterol and fluticasone in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2003;361:449-56

- Szafranski W, Cukier A, Ramirez A, et al. Efficacy and safety of budesonide/formoterol in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J 2003;21:74-81

- Luccioni C, Donner CF, De Benedetto F. I costi della broncopneumonopatia cronica ostruttiva: la fase prospettica dello studio ICE (Italian costs for exacerbations in COPD). Pharmacoeconomics (Italian Research Articles) 2005;7:119-34

- Dal Negro RW, Rossi A, Cerveri I. The burden of COPD in Italy: results from the Confronting COPD survey. Respir Med 2003;97:S43-50

- Brusasco V, Hodder R, Miravitlles M. Health outcomes following treatment for six months with once daily tiotropium compared with twice daily salmeterol in patients with COPD. Thorax 2003;58:399-404

- Casaburi R, Mahler DA, Jones PW. A long-term evaluation of once-daily inhaled tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J 2002;19:217-24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.02.0269802. Accessed July 2015

- Britton M. The burden of COPD in the UK: results from the Confronting COPD survey. Resp Med 2003;97(C Suppl):S71-9. http://dx.doi.org/. Accessed July 2015

- Griffiths TL, Phillips CJ, Davies S, et al. Cost effectiveness of an outpatient multidisciplinary pulmonary rehabilitation programme. Thorax 2001;56:779-84

- Hertel N, Kotchie RW, Samyshkin Y, et al. Cost-effectiveness of available treatment options for patients suffering from severe COPD in the UK: a fully incremental analysis. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2012;7:183-99

- Mills EJ, Druyts E, Ghement I, et al. Pharmacotherapies for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a multiple treatment comparison meta-analysis. Clin Epidemiol 2011;3:107-29

- Cleemput I, Van Wilder P, Vrijens F, et al. Guidelines for pharmacoeconomic evaluations in Belgium. Health technology assessment (HTA) Brussels: Health Care Knowledge Centre (KCE), 2008. p.78C

- Dahl R, Greefhorst LA, Nowak D. Inhaled formoterol dry powder versus ipratropium bromide in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164:778-84

- Rodriguez Roisin R, Rabe KF, Anqueto A. Workshop report: Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD: updated 2009. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, MD USA, www.goldcopd.com. Accessed April 2012

- Koopmanschap MA, Rutten FF, van Ineveld BM. The friction cost method for measuring indirect costs of disease. J Health Econ 1995;14:171-89

- Boyd G, Morice AH, Pounsford JC. An evaluation of salmeterol in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Eur Respir J 1997;10:815-21

- Kerwin EM, D’Urzo AD, Gelb AF, et al. Efficacy and safety of a 12-week treatment with twice-daily aclidinium bromide in COPD patients (ACCORD COPD I). COPD 2012;9:90-101

- Quanjer PH, Tammeling GJ, Cotes JE, et al. Lung volumes and forced ventilatory flows. Report Working Party Standardization of Lung Function Tests, European Community for Steel and Coal. Official Statement of the European Respiratory Society. Eur Respir J Suppl 1993;16:5-40

- Rutten-van Molken M, Lee TA. Economic modeling in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2006;3:630-4

- Yu AP, Yang H, Wu EQ, et al. Incremental third-party costs associated with COPD exacerbations: a retrospective claims analysis. J Med Econ 2011;14:315-23

- Niewoehner DE, Rice K, Cote C, et al. Prevention of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with tiotropium, a once-daily inhaled anticholinergic bronchodilator: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2005;143:317-26

- Donohue JF, van Noord A, Bateman ED. A 6-month, placebocontrolled study comparing lung function and health status changes in COPD Patients treated with tiotropium or salmeterol. Chest 2002;122:47-55

- Aaron SD, Vandemheen K, Fergusson D. The Canadian Optimal Therapy of COPD Trial: design, organization and patient recruitment. Can Respir J 2004;11:581-5

- Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, Fergusson D. Tiotropium in combination with placebo, salmeterol, or fluticasone-salmeterol for treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:545-55

- O’Reilly JF, Williams AE, Rice L. Health status impairment and costs associated with COPD exacerbation managed in hospital. Int J Clin Pract 2007;61:1112-20

- Roede BM, Bindels PJ, Brouwer HJ, et al. Antibiotics and steroids for exacerbations of COPD in primary care: compliance with Dutch guidelines. Br J Gen Pract 2006;56:662-5.

- Pennachio DL. Exclusive survey. Fees and reimbursements. Med Econ 2003;80:96-109

- Oostenbrink JB, Buijs-Van Der Woude T, et al. Unit costs of inpatient hospital days. PharmacoEconomics 2003;212:63-71

- Oostenbrink JB, Rutten-van Mölken MPMH. Resource use and risk factors in high cost exacerbations of COPD. Respir Med 2004;98:883-91

- Paterson C, Langan CE, McKaig GA. Assessing patient outcomes in acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis: the measure your medical outcome profile (MYMOP), medical outcomes study 6-item general health survey (MOS-6A) and Euro-Qol (EQ-5D). Qual Life Res 2000;9:521-7

- Spencer S, Jones PW. Time course of recovery of health status following an infective exacerbation of chronic bronchitis. Thorax 2003;58:589-93

- Donohue J, Fogarty C, Lotvall J, et al. Once-daily bronchodilators for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: indacaterol vs. tiotropium. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;155:e62

- Kornmann O, Dahl R, Centanni S. Once-daily indacaterol vs twice-daily salmeterol for COPD: a placebo controlled comparison. Eur Respir J 2011;37:273-9

- Tashkin DP. Is a long-acting inhaled bronchodilator the first agent to use in stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Curr Opin Pulm Med 2005;11:121-8

- Stahl E, Lindberg A, Jansson SA, et al. Health-related quality of life is related to COPD disease severity. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2005;3:56

- Kornmann O, Dahl R, Centanni S. Once-daily indacaterol versus twice-daily salmeterol for COPD: a placebo-controlled comparison. Eur Respir J 2011;37:273-9

- Rutten-van Molken MP, Hoogendoorn M, Lamers L. Holistic preferences for 1-year health profiles describing fluctuations in health: the case of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PharmacoEconomics 2009;27:465-77

- Dahl R, Jadayel D, Alagappan VKT, et al. Efficacy and safety of QVA149 compared to the concurrent administration of its monocomponents indacaterol and glycopyrronium: the BEACON study. Int J COPD 2013;8:501e8

- Vogelmeier CF, Bateman ED, Pallante J, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily QVA149 compared with twice-daily salmeteroldfluticasone in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (ILLUMINATE): a randomised, double-blind, parallel group study. Lancet Respir Med 2013;51:e60

- Mahler DA, Wire P, Horstman D, et al. Effectiveness of fluticasone propionate and salmeterol combination delivered via the Diskus device in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:1084-91

- Jansson SA, Andersson F, Borg S, et al. Costs of COPD in Sweden according to disease severity. Chest 2002;122:1994-2002

- Jansson SA, Backman H, Stenling A, et al. Health economic costs of COPD in Sweden by disease severity has it changed during a ten years period? Respir Med 2013;107:1931-8

- Lindberg A, Larsson LG, Muellerova H, et al. Up-to-date on mortality in COPD e report from the OLIN study. BMC Pulmonary Med 2012;12:1

- Rutten-van Molken MP, Oostenbrink JB, Tashkin DP, et al. Does quality of life of COPD patients as measured by the generic EuroQol five-dimension questionnaire differentiate between COPD severity Stages? Chest 2006;130:1117-28

- Miravitlles M, Murio C, Guerrero T, et al. Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis and COPD. Chest 2002;121:1449-55

- Miravitlles M, Ferrer M, Pont A. Effect of exacerbations on quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a 2 year follow up study. Thorax 2004;59:387-95

- Badia X, Roset M, Herdman M, et al. A comparison of United Kingdom and Spanish general population time trade-off values for EQ-5D health states. Med Decis Making 2001;21:7-16

- Bateman ED, Rabe KF, Calverley PM, et al. Roflumilast with long-acting β2 agonists for COPD: influence of exacerbation history. Eur Respir 2011;38:553-60

- Calverley PM, Rabe KF, Goehring UM, et al. Roflumilast in symptomatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: two randomised clinical trials. Lancet 2009;374:685-94

- Rutten-van Mölken MP, Hoogendoorn M, Lamers LM. Holistic preferences for 1-year health profiles describing fluctuations in health: the case of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PharmacoEconomics 2009;27:465-77

- Rabe KF. Update on roflumilast, a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Br J Pharmacol 2011;163:53-67

- Ekberg-Aronsson M, Pehrsson K, Nilsson JA, et al. Mortality in GOLD stages of COPD and its dependence on symptoms of chronic bronchitis. Respir Res 2005;6:98. doi:10.1186/465-9921-6-98

- Prescott-Clarke P, Primatesta P. Health survey for England 1996. 2: London, 1998

- Brazier J, Usherwood T, Harper R. Deriving a preference based single index from the UK SF-36 Health Survey. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:1115-28

- Hoogedorn M, Feenstra TL, Asukai Y, et al. Cost-effectiveness models for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: cross-model comparison of hypothetical treatment scenarios. Value Health 2014;17:525-36