Abstract

Objective:

Disease-modifying therapy (DMT) for multiple sclerosis (MS) can reduce relapses and delay progression; however, poor adherence and persistence with DMT can result in sub-optimal outcomes. The associations between DMT adherence and persistence and inpatient admissions and emergency room (ER) visits were investigated.

Methods:

Patients with MS who initiated a DMT in a US administrative claims database were followed for 1 year. Persistence to initiated DMT was measured as the time from DMT initiation to discontinuation (a gap of >60 days without drug ‘on hand’) or end of 1-year follow-up. Adherence to initiated DMT was measured during the persistent period and was operationalized as the medication possession ratio (MPR). Patients with an MPR <0.80 were considered non-adherent. Claims during the 1-year follow-up period were evaluated for the presence of an all-cause inpatient admission or an ER visit. Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) for inpatient admission or ER visit comparing persistent vs non-persistent and adherent vs non-adherent patients were estimated using logistic regression models adjusted for patient characteristics.

Results:

The final sample included 16,218 patients. During the 1-year follow-up period, 35.3% of patients discontinued their initiated DMT and 13.9% were not adherent while on therapy. During that same period, 10.0% of patients had an inpatient admission and 24.9% had an ER visit. The likelihoods of inpatient admission and ER visit were significantly decreased in persistent patients (AOR [95% CI] = 0.50 [0.45, 0.56] and 0.65 [0.60, 0.69], respectively) and in adherent patients (AOR [95% CI] = 0.83 [0.71, 0.97] and 0.86 [0.77, 0.95], respectively).

Conclusions:

Persistence and adherence with initiated DMT are associated with decreased likelihoods of inpatient admission or ER visit, which may translate to improved clinical outcomes.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic and inflammatory degenerative disease of the central nervous systemCitation1,Citation2. A recent US study of commercially insured patients found that almost three-quarters of patients with an MS diagnosis were womenCitation3 and an international systematic review found that the overall incidence rate was 3.6 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI = 3.0–4.2) among women and 2.0 (95% CI = 1.5–2.4) among menCitation4. The majority of patients with MS first experience a relapsing-remitting form of MS in which there are acute episodes of neurological dysfunction followed by remissionCitation1,Citation5. Approximately 15–20% of patients have progressive disease from the onsetCitation1,Citation5. In both types of MS, the disease progresses over time and a patient’s functional disability worsens, eventually becoming irreversibleCitation1,Citation6. Currently, there are several approved disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) for relapsing MS in the US: glatiramer acetate (first approved in 1996), mitoxantrone (2000), interferon β-1a (1996), interferon β-1b (1993), natalizumab (approved in 2004, withdrawn, and re-entered the market in 2006), fingolimod (2010), teriflunomide (2012), dimethyl fumarate (2013), and alemtuzumab (2014)Citation7. The primary purposes of DMT therapy among patients with MS are to decrease the incidence and severity of relapses and to reduce disability progressionCitation1,Citation8.

Adherence to prescribed frequency and dosing of DMTs can be challenging for patients who experience symptoms of forgetfulness, treatment fatigue and depression, treatment-related injection-site reactions, and a perceived lack of treatment efficacyCitation9. Low adherence has been shown to increase the risk of relapsesCitation10–13 and inpatient and emergency room (ER) visitsCitation10–12. Also, discontinuation of therapy, also known as non-persistence, can be associated with costly inpatient admissions and other medical care; a study of patients initiating interferons or glatiramer acetate found that patients who discontinued treatment or switched to another DMT had higher non-pharmacy medical costs in the 18 months following a switch or discontinuation ($12,551 for discontinuers and $15,532 for switchers) than did those who remained on their initial therapy ($9399)Citation14. The researchers also found that one-third of patients discontinued therapy for ≥90 days compared with 11% of patients who switched without a break in therapyCitation14.

Although adherence and persistence have been studied in MS, there have been few studies that have investigated the effects of adherence and persistence on inpatient admissions and ER visitsCitation10–13. Of these studies, none included any oral medications or investigated the effects of persistence separately from adherence. The objective of this study was to address this gap in the literature by investigating separately the impact of persistence (i.e., how long a patient remains on a therapy) and the impact of adherence (i.e., how compliant a patient is to the prescribed frequency while on therapy) to initiated DMT on inpatient admissions and on ER visits in a population of patients with MS treated with approved DMTs.

Patients and methods

Data source

This analysis was conducted with data from the Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters and Medicare Supplemental Databases, which contain administrative healthcare claims and paid amounts for inpatient and outpatient medical and outpatient pharmacy services. Individuals in the Commercial database are insured through a variety of private health plans, including preferred provider organizations, point-of-service plans, indemnity plans, and health maintenance organizations. The Medicare database contains claims for individuals insured through Medicare supplemental insurance paid for by employers. Both Medicare-covered and insurer-covered services are included due to co-ordination of benefits. All claims and encounters for which Medicare does not pay 100% of the costs are included. The Commercial and Medicare databases included information on over 40 million unique covered lives in 2011 alone.

The study database satisfies the conditions set forth in Sections 164.514 (a)–(b)1ii of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 privacy rule regarding the determination and documentation of statistically de-identified data. Because this study used only de-identified patient records and does not involve the collection, use, or transmittal of individually identifiable data, Institutional Review Board approval to conduct this study was not necessary.

Patient selection

Patients were selected for inclusion in the study sample based on several inclusion and exclusion criteria. First, patients were required to have ≥1 non-diagnostic medical claim with a diagnosis of MS (International Classification of Diseases, Clinical Modification, Ninth Revision [ICD-9-CM] 340) in any position between January 1, 2009 and December 31, 2011. Diagnostic claims (e.g., laboratory tests and magnetic resonance imaging) were not evaluated because they may represent diagnostic procedures to rule out MS. Patients with MS were then required to have ≥2 outpatient prescriptions with a National Drug Code or outpatient medical claims with a Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System Code for an approved DMT for MS (natalizumab, intramuscular interferon β-1a, subcutaneous interferon β-1a, subcutaneous interferon β-1b, glatiramer acetate, or fingolimod) during the same time period. The two claims must have been for the same DMT, with the second of the two claims occurring within 180 days of the first and no claims for other DMTs in between the two claims. The date of the first claim is referred to as the index date, and the specific DMT is referred to as the index drug. Dimethyl fumarate, teriflunomide, and alemtuzumab were not included as potential index drugs because of their more recent approval dates. It should be noted that fingolimod was approved in September 2010 and, therefore, was not available for the entire study period. Additionally, all patients were required to be 18 years of age or older and to have been continuously enrolled in medical and prescription coverage for ≥6 months before the index date (pre-period) and ≥1 year following the index date (follow-up period). During the pre-period, patients were required to have no claims for the same DMT initiated on the index date. Patients were allowed to have claims for other DMTs or other types of drugs used to treat MS symptoms during the pre- period. Therefore, patients were not required to be treatment-naive to all DMT therapies. Claims for other DMTs to treat MS were allowed after the 180-day period; thus, add-on combination therapy was allowed.

Patients who initiated self-injectable DMTs, which typically are billed through pharmacy claims, but had only medical claims for the DMT were excluded. Patients with a claim for mitoxantrone and those with claims for two different DMTs on the index date were also excluded. These patients likely have clinical characteristics different from those of other patients with MS, such as more severe disease. Lastly, patients with claims for a non-specific Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System Code for interferon β-1a, which could not be assigned to intramuscular or subcutaneous administration using claims history, were excluded.

Dependent variables

The primary dependent variables were the presence of an all-cause inpatient admission and the presence of an all-cause ER visit. These healthcare utilization outcomes were captured during the 1-year follow-up period.

Independent variables and covariates

The primary independent variables were persistence and adherence to the index MS drug during the 1-year follow-up period in an intent-to-treat study design, as is commonly used in clinical trials and claims-based analyses. Persistence to index drug was captured as a binary variable for discontinuation of the index MS drug vs no discontinuation. Discontinuation was defined as a gap of >60 days without a supply of the index MS drug ‘on hand’, and the date of discontinuation was the last day with supply of the index drug available prior to the gap. Note that a switch to another DMT was counted as a discontinuation of the index MS drug. Adherence to index drug was calculated during the persistent period. Measured as the medication possession ratio (MPR), it was calculated by summing the days’ supply of the index MS drug during the time from the index date to either the discontinuation date or 1-year follow-up, if the patient did not discontinue and dividing by the number of days persistent on therapy. Patients with an MPR ≥0.80 were considered adherent. MPR was measured over the variable-length persistent period because the research question of interest was adherence while on therapy, and measuring MPR over a fixed follow-up (i.e., 1-year) would capture similar information as persistence, which was already measured. For prescription claims for DMTs, the days’ supply field was used to calculate persistence and adherence, while for outpatient medical claims for DMTs, days’ supply was estimated based on FDA-approved prescribing information. For example, medical claims for natalizumab were assumed to have a ‘days supply’ of 28 days.

Covariates measured in the analysis included demographic, clinical, and treatment characteristics. Demographic characteristics, including age and sex, were measured on the index date, as were characteristics of the insurance plan. Clinical characteristics were captured using claims during the 6-month pre-period and included the Deyo Charlson Comorbidity IndexCitation15, which is a measure of overall comorbidity burden, and MS-specific co-morbid conditions, such as optic neuritis, bladder dysfunction, and neuropathic pain. Patients with ≥1 non-diagnostic inpatient or outpatient medical claim with the relevant diagnosis code in any position were considered to have a co-morbid condition. Pre-period claims for intravenous, self-injectable, or oral corticosteroid and other MS therapies were also identified. Patients with no evidence of other DMTs during the 6-month pre-period were defined as treatment-naive.

All-cause and MS-related cost and utilization were also measured during the pre-period. Costs were the paid amount on claims, including out-of-pocket costs. Inpatient claims with a principal diagnosis of MS, outpatient claims with a primary diagnosis of MS, outpatient claims for specific MS-related diagnostic procedures, outpatient infusion claims for natalizumab, and pharmacy claims for DMTs (including teriflunomide, which was available later in the study period), methotrexate, corticosteroids, and cyclosporine were defined as being related to MS. Patient cost-sharing for a 30-day supply of the index DMT was estimated using a cost-sharing measure. The average cost-sharing amount (co-payments plus co-insurance payments) for all claims for the specific DMT within an insurance plan in a given year was computed and assigned to each patient based on plan enrollment and year of index dateCitation16. Patients enrolled in plans with less than five claims for a specific DMT were assigned a missing value for the index, as the average cost-sharing amount may not be reliable.

Analysis

Bivariate analyses of patient characteristics comparing persistent vs non-persistent patients, adherent vs non-adherent patients, and patients with an inpatient admission or an ER visit vs those without were conducted. Continuous variables were compared with a t-test and categorical variables with Chi-square tests. Four multivariable logistic regression models were fit to describe the association between persistence and adherence to index MS drug and healthcare utilization. Odds ratios were adjusted for the following patient characteristics that may confound the relationship between persistence or adherence and inpatient admission or ER visit: gender, age group, urbanicity, region, health plan type, pre-period Charlson Comorbidity Index, pre-period corticosteroid use, treatment-naive status, pre-period inpatient admission, pre-period ER visit and log of pre-period total expenditures. P-values were compared with a critical alpha of 0.05.

Results

There were 174,182 patients with ≥1 claim with an MS diagnosis between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2011. Of those patients, 38.0% (n = 66,115) had two prescriptions for a DMT. The age and continuous enrollment criteria excluded an additional 21,419 patients. An additional 28,256 patients were excluded because they had evidence of the index DMT during the pre-period. Another 129 patients were excluded due to the technical reasons mentioned in the Methods section (73 medical claims for DMTs typically billed using pharmacy claims, 12 interferon β-1a codes that could not be assigned to intramuscular or subcutaneous, 44 claims for other DMTs in between the two index DMT claims), and 93 were excluded because they had claims for mitoxantrone. The final sample comprised 16,218 patients. Of these patients, 10.4% initiated an infused medication, 17.4% initiated an intramuscular-injected medication, 66.0% initiated a subcutaneous-injected medication and 6.1% initiated an oral medication.

The mean age of patients in the sample was 44.5 years (SD = 10.8), and the majority of the patients were female (77.1%, ). The groups of patients classified as persistent and adherent were significantly older and had proportionately more men than those classified as non-persistent and non-adherent. Nearly all patients were insured through commercial plans. Overall, 54.0% of patients had a cost share of ≤$50 for a 30-day supply of MS study drug. The adherent patient group and persistent patient group had a higher proportion of patients with patient cost shares <$25 than did the non-adherent and non-persistent groups. The most common co-morbid conditions diagnosed during the pre-period were other chronic pain (31.0%), depression (11.9%), and neuropathic pain (10.2%, ). Other chronic pain and neuropathic pain were significantly more prevalent among persistent and adherent patients, whereas diagnosed depression was significantly less common among the persistent and adherent patients. The majority of patients had no claims for DMTs in the pre-period (79.9%), with significantly fewer treatment-naive patients among the persistent and adherent groups than among the non-persistent and non-adherent groups, respectively. A larger proportion of persistent patients and adherent patients had ≥1 claim for oral, self-injectable, or intravenous corticosteroids during the pre-period compared with non-persistent and non-adherent patients. Total pre-period all-cause and MS-related healthcare costs were significantly higher in persistent and adherent patients compared with non-persistent and non-adherent patients. No significant differences existed for the presence of pre-period all-cause inpatient admission. A greater proportion of adherent patients had a pre-period all-cause ER visit.

Table 1. Patient demographics, insurance plans, and cost-sharing index stratified by persistent vs non-persistent and adherent vs non-adherent status.

Table 2. Patient conditions and utilization during the 6-month pre-index period stratified by persistent vs non-persistent and adherent vs non-adherent status.

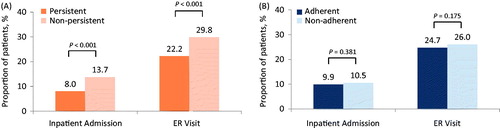

The mean time persistent on the index DMT during the year following initiation was 290.1 days (SD = 111.6; ). Overall, 35.3% of patients discontinued the index DMT during the follow-up year. The mean MPR during the persistent period was 0.92 (SD = 0.13), and 86.1% of patients were categorized as adherent. During the 1-year follow-up period, 10.0% of patients had ≥1 all-cause inpatient admission and 24.9% had ≥1 all-cause ER visit. In unadjusted analyses, a significantly greater proportion of non-persistent patients had an inpatient admission (13.7% vs 8.0%) or an ER visit (29.8% vs 22.2%) compared with persistent patients (). A similar trend was observed among adherent and non-adherent patients, but was not statistically significant (). A comparison between patients with and those without an inpatient admission and between those with and without an ER visit showed that patients with an inpatient admission or an ER visit had worse persistence and adherence, although differences in adherence failed to reach statistical significance in unadjusted analysis (). Four multivariable logistic regression models were fit while controlling for the covariates presented in . In adjusted models, both persistent patients and adherent patients had significantly lower adjusted odds of having an inpatient admission or an ER visit in the year following initiation of index therapy. The magnitude of the effect was larger for persistence (). Other factors associated with inpatient admission and ER visit were indicators of poor health such as higher corpus callosum index CCI, pre-period ER visit, and pre-period healthcare expenditures.

Figure 1. Unadjusted proportions of patients with an inpatient admission or ER visit during the 1-year follow-up period. (A) Persistent and non-persistent patients. (B) Adherent and non-adherent patients.

Table 3. Persistence and adherence during 1-year follow-up period stratified by presence of inpatient admission or ER visit during 1-year follow-up period.

Table 4. Adjusted odds ratios of having an inpatient admission or ER visit during the 1-year follow-up period.

Discussion

In this claims-based analysis, we found that patients with MS who were non-persistent with initiated DMT were more likely to have an inpatient admission or an ER visit over the 1-year period following initiation. Patients who were non-adherent to their index DMT during the time they were persistent on therapy were also more likely to have an inpatient admission or ER visit in adjusted models, but the association was not as strong as it was for persistence. The reduction in likelihood of inpatient admission or ER visit may result in a reduction of medical costs, which may be impactful given that medical costs over a 2-year period for patients with MS have been estimated to be $8136 (2007 US$)Citation10.

Overall, we found that adherence to DMTs was fairly high during the persistent period, with a mean MPR of 0.92 (SD = 0.13), and 86% of patients achieved the adherence threshold of an MPR ≥0.8. However, non-persistence was observed to a greater degree, with 35% of patients discontinuing their index DMT during 1 year. Our method of computing the MPR during the persistent period is sometimes referred to as variable MPRCitation17. High values of adherence to DMT, measured using a variable MPR over 1 year of follow-up, have been found in other studies of MS. A study of eight different diseases and conditions found adherence to be the highest in MSCitation18. A study by Agashivala et al.Citation19 of five DMTs for MS, including fingolimod, found high MPRs and that 71–90% of patients achieved the adherence threshold, depending on treatment-naive status and DMT. That study also found that 44–64% of treatment-naive users and 26–57% of treatment-experienced users were non-persistent (had a supply gap of 60 days or more) during the first year.

Our study presented crude bivariate comparisons of several patient factors, some of which have been shown to have an impact on persistence and adherence. For example, we found that groups of patients who were adherent and persistent both had slightly higher proportions of men and older patients than did the non-adherent and non-persistent groups. Other studies have found older age to be associated with slightly improved persistenceCitation9,Citation19–21. Men with MS have been found to have slightly better persistence and adherence than women with MS, but the results were not always statistically significantCitation19–21. One study found that men had significantly better adherence and persistence than did womenCitation20, and another study found that sex was not a significant determinant of persistenceCitation19. A study of second-line therapy found that men had better adherence, but gender was not statistically significant in models of persistenceCitation21. In our study, the groups of adherent and persistent patients had slightly higher proportions of patients with patient cost shares <$25 for a 30-day supply than did the groups of non-adherent and non-persistent patients. Increased patient cost-sharing, particularly when insurance plans use co-insurance (i.e., patients are responsible to pay for a percentage of drug price rather than fixed co-payments), has been associated with reduced adherence to DMTs in MSCitation22. In our study, significantly fewer DMT treatment-naive patients were persistent or adherent compared with those who had another DMT in the previous 6 months. The aforementioned study by Agashivala et al.Citation19 separated their analyses into naive and experienced groups, and their results indicate that the effect of treatment-naive status depends on the index drug. A survey study by Treadaway et al.Citation9 found that treatment-naive patients were more likely to be adherent than were those who had previously taken other DMTs, and they suggested that non-adherence could be a pretext for trying new drugs. Our bivariate analysis found that a higher proportion of adherent and persistent patients had ≥1 claim for corticosteroids during the pre-period. Another study also reported that patients who had used corticosteroids during the pre-index period were more likely to be adherent to their DMT, but the effect on persistence was not significantCitation21. One co-morbid condition that has been found to adversely affect adherence is depressionCitation9,Citation23,Citation24. Our bivariate results confirm this finding, as we found a higher proportion of patients with depression in the non-persistent and non-adherent groups.

We found that patients who were persistent with one DMT during 1 year were half as likely to have an inpatient admission and a third less likely to have an ER visit compared with those who were non-persistent. Patients who were adherent to therapy were also less likely to have an inpatient admission or an ER visit. Four other studies found that adherence to DMT is associated with better clinical outcomes, leading to fewer inpatient admissions, fewer ER visits, and lower relapse ratesCitation10–13. These studies used a fixed MPR measure—days supplied divided by total follow-up days—which usually results in lower average MPR values than does the variable MPR method, which was used in our studyCitation17. Adherence computed using the fixed MPR method is affected by both persistence and by adherence to prescribed dosing.

In a 2-year study of employed adults aged ≤62 years receiving DMT for MS (interferons, glatiramer acetate, or natalizumab), Ivanova et al.Citation10 found that significantly fewer DMT-adherent than non-adherent patients had inpatient visits (7.6% vs 12.5%), ER visits (8.9% vs 15.0%), and severe relapses—defined as an inpatient admission or an ER visit with an MS diagnosis (12.5% vs 19.5%). After risk adjustment, the severe relapse rates were 12.4% for adherent patients, compared with 19.9% for non-adherent patientsCitation10. Similarly, in a study of patients with MS aged ≤64 years who were DMT-naive for 6 months and initiated an interferon or glatiramer acetate, Tan et al.Citation11 found that MS-related inpatient admissions (adjusted odds ratio [OR] = 0.63; 95% CI = 0.47–0.83), MS-related ER visits (adjusted OR = 0.80; 95% CI = 0.60–1.07), and MS relapses (adjusted OR = 0.71; 95% CI = 0.59–0.85) were less likely among patients who were adherent to any DMT therapy during 1 year of follow-up. In a 2-year study of different adherence thresholds for glatiramer acetate, Oleen-Burkey et al.Citation13 found that patients who had a fixed MPR of ≥0.7 had a significantly lower probability of relapse than did patients with a fixed MPR <0.7. Additionally, adherence levels >0.7 in 2 years lowered the risk of relapse even moreCitation13. Patients who met lower MPR thresholds, such as 0.5, did not have any improvement in the risk of relapseCitation13. Finally, a multi-year study of interferon β therapy conducted by Steinberg et al.Citation12 found that high adherence was associated with a lower risk of relapses, inpatient admissions and ER visits, although most relationships were not statistically significant. These four analyses did not focus on the potential effect of persistence and did not include oral medications.

This study was subject to a number of limitations common among analyses of claims databases. First, when using claims data to analyze medications dispensed at pharmacies, it is not known whether the patients injected all of their medication each time or how many injections or pills they had left when they decided to discontinue the medication. Second, it is not possible to determine how long patients have had MS, how severe their symptoms are, and whether they have relapsing-remitting, secondary-progressive, or primary-progressive MS as there is only one ICD-9-CM diagnosis code for MS. Third, the analysis of persistence was conducted over a fixed 1-year period, so it is possible that some inpatient admissions occurred after discontinuation and others led to discontinuation. Therefore, causal inference should be made with caution, as temporality between exposure and outcome was not established. Fourth, patients who switched to another DMT were counted as ‘discontinuers’. Overall adherence to and persistence with MS medications in general were not captured as the objective was to measure these compliance variables with respect to initiated index drug in an intent-to-treat analysis. Therefore, a patient who switched to a different MS medication was considered non-persistent. Another study, conducted over an 18-month period, found that 11% of patients switched DMTs while 33% discontinued DMTsCitation14. Fifth, claims data are generated for billing, not research, and, therefore, miscoding or lack of coding of diagnoses may exist. For this reason, all-cause inpatient admissions and ER visits were evaluated. However, it is possible that some of the inpatient admissions and ER visits were not MS-related. Sixth, treatment-naive individuals initiating their first DMT are likely very different from treatment-experienced individuals initiating a new DMT. Prior treatment was included as a covariate in multivariable models; however, residual confounding may have biased the study findings. Lastly, the two more recent oral medications, teriflunomide and dimethyl fumarate, were not evaluated as potential index medications. Now that additional data on these medications are available, future research could include patients initiating these medications and could potentially compare adherence and persistence by route of administration.

Conclusions

Among a large group of patients who initiated a DMT (natalizumab, interferon β-1a, interferon β-1b, glatiramer acetate, fingolimod) for MS, persistence, and to a lesser degree adherence, to initiated DMT during the first year were associated with reductions in the likelihood of an all-cause inpatient admission and ER visit. As with other MS studies that used a similar definition of adherence, a large portion of patients (86%) were adherent. However, only 65% of patients continued on the drug during the first year. Although this study did not assess causality, it points to the need for further improvement in persistence with DMT therapy in MS, which may translate into fewer inpatient admissions or ER visits.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This analysis was funded by Genentech, Inc.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

NPT, EY, and DH are employees of Genentech, Inc; SC and AMF are employees of Truven Health Analytics. Support for third-party writing assistance for this manuscript was provided by Genentech, Inc. JME peer reviewers were financially compensated for their time.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jerry Kagan of Truven Health Analytics for programming and data analyses, and Greg Lenhart of Truven Health Analytics for statistical analyses. Third-party writing assistance was provided by Health Interactions.

References

- Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet 2008;372:1502-17

- Weiner HL. Multiple sclerosis is an inflammatory T-cell-mediated autoimmune disease. Arch Neurol 2004;61:1613-15

- Margolis JM, Fowler R, Johnson BH, et al. Disease-modifying drug initiation patterns in commercially insured multiple sclerosis patients: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Neurol 2011;11:122

- Alonso A, Hernan MA. Temporal trends in the incidence of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Neurology 2008;71:129-35

- Confavreux C, Vukusic S, Moreau T, et al. Relapses and progression of disability in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2000;343:1430-8

- Kister I, Bacon TE, Chamot E, et al. Natural history of multiple sclerosis symptoms. Int J MS Care 2013;15:146-58

- National Multiple Sclerosis Society. The MS disease-modifying medications. http://www.nationalmssociety.org/NationalMSSociety/media/MSNationalFiles/Brochures/Brochure-The-MS-Disease-Modifying-Medications.pdf. Accessed May 20, 2015

- Owens GM, Olvey EL, Skrepnek GH, et al. Perspectives for managed care organizations on the burden of multiple sclerosis and the cost-benefits of disease-modifying therapies. J Manag Care Pharm 2013;19:S41-53

- Treadaway K, Cutter G, Salter A, et al. Factors that influence adherence with disease-modifying therapy in MS. J Neurol 2009;256:568-76

- Ivanova JI, Bergman RE, Birnbaum HG, et al. Impact of medication adherence to disease-modifying drugs on severe relapse, and direct and indirect costs among employees with multiple sclerosis in the US. J Med Econ 2012;15:601-9

- Tan H, Cai Q, Agarwal S, et al. Impact of adherence to disease-modifying therapies on clinical and economic outcomes among patients with multiple sclerosis. Adv Ther 2011;28:51-61

- Steinberg SC, Faris RJ, Chang CF, et al. Impact of adherence to interferons in the treatment of multiple sclerosis: a non-experimental, retrospective, cohort study. Clin Drug Investig 2010;30:89-100

- Oleen-Burkey MA, Dor A, Castelli-Haley J, et al. The relationship between alternative medication possession ratio thresholds and outcomes: evidence from the use of glatiramer acetate. J Med Econ 2011;14:739-47

- Reynolds MW, Stephen R, Seaman C, et al. Healthcare resource utilization following switch or discontinuation in multiple sclerosis patients on disease modifying drugs. J Med Econ 2010;13:90-8

- Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:613-19

- Gibson TB, Jing Y, Kim E, et al. Cost-sharing effects on adherence and persistence for second-generation antipsychotics in commercially insured patients. Manag Care 2010;19:40-7

- Kozma CM, Dickson M, Phillips AL, et al. Medication possession ratio: implications of using fixed and variable observation periods in assessing adherence with disease-modifying drugs in patients with multiple sclerosis. Patient Prefer Adherence 2013;7:509-16

- Rolnick SJ, Pawloski PA, Hedblom BD, et al. Patient characteristics associated with medication adherence. Clin Med Res 2013;11:54-65

- Agashivala N, Wu N, Abouzaid S, et al. Compliance to fingolimod and other disease modifying treatments in multiple sclerosis patients, a retrospective cohort study. BMC Neurol 2013;13:138

- Halpern R, Agarwal S, Borton L, et al. Adherence and persistence among multiple sclerosis patients after one immunomodulatory therapy failure: retrospective claims analysis. Adv Ther 2011;28:761-75

- Halpern R, Agarwal S, Dembek C, et al. Comparison of adherence and persistence among multiple sclerosis patients treated with disease-modifying therapies: a retrospective administrative claims analysis. Patient Prefer Adherence 2011;5:73-84

- Dor A, Lage MJ, Tarrants ML, et al. Cost sharing, benefit design, and adherence: the case of multiple sclerosis. Adv Health Econ Health Serv Res 2010;22:175-93

- Tarrants M, Oleen-Burkey M, Castelli-Haley J, et al. The impact of comorbid depression on adherence to therapy for multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Int 2011;2011:271321

- Mohr DC, Goodkin DE, Likosky W, et al. Treatment of depression improves adherence to interferon β-1b therapy for multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol 1997;54:531-3