Abstract

Objectives To identify how many RA patients newly-initiated on bDMARD therapy switch to another bDMARD during the first year of treatment; to evaluate the factors and reasons associated with bDMARD switching; and to compare the RA-related healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) and costs between switchers vs non-switchers during the post-index period.

Methods A retrospective cohort study was conducted in RA patients using the Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) database with the study time period of January 1, 2007 to December 31, 2012. The index date was defined as the date of the first bDMARD prescription. Patients had to have continuous membership eligibility with drug benefit and no prior history of bDMARD during the 24 months prior to the index date. bDMARD switching was defined as a different bDMARD claim during post-index. A multivariable logistic regression model was used to evaluate factors associated with switchers vs non-switchers. Chart notes were reviewed to evaluate reasons for switching from index bDMARD. RA-related HCRU use and costs were evaluated using a generalized linear model (GLM) with gamma distribution and log link function.

Results Two hundred and fifty-one patients (12%) switched from their index bDMARD to a different bDMARD during the post-index period. bDMARD switchers were more likely to be female, of Asian/Pacific race, younger than ≤65 years of age, overweight, CCI score ≤2, initiating etanercept or adalimumab, and have a commercial insurance plan compared to non-switchers. Reasons for switching were related mostly to lack or loss of efficacy (∼51%); bDMARD switchers had overall mean adjusted RA related total costs that were 25% higher (p = 0.04) compared to non-switchers.

Conclusion It is important for RA patients to receive appropriate therapy and consider bDMARD with different mechanisms of action to decrease subsequent switching, and decrease overall RA related costs as shown in this study.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a systemic inflammatory disease which manifests to affect multiple joints of the bodyCitation1,Citation2. It is an autoimmune condition that causes pain, swelling, and redness; it can also cause premature mortality, disability, and compromised quality-of-lifeCitation2. The etiology or cause of RA is unknown and many cases are believed to result from an interaction between genetic factors and environmental exposuresCitation1–3. The incidence of RA is typically 2–3-times higher in women than men and the onset of RA, in both women and men, is highest among those in their sixtiesCitation3. The prevalence of RA is believed to range from 0.5–1.0% in the general populationCitation3, and prevalence estimates derived from 2001-2005 US ambulatory healthcare system data estimated that 1.5 million US adults have RACitation4. There is no cure for RA; however, there are many different therapies used to treat RA patients with the goal to prevent deformed joints.

The treatment approach for RA patients has become more aggressive over recent years with prescription of non-biologic DMARDs within 3 months of diagnosis to reduce disease activity and prevent joint deformity. Treatment guidelines have also changed with the increasing array of bDMARD availableCitation5,Citation6, along with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and glucocorticoids. Use of bDMARD has increased over the past 15 yearsCitation7, and current guidelines recommend the early use of biologic agents following an insufficient response to initial non-biologic DMARD therapy. Additionally, the 2013 EULAR guidelines have evolved and recommend monitoring should be frequent in active disease (every 1–3 months); and if there is no improvement by at most 3 months after the start of treatment or the target has not been reached by 6 months, therapy should be adjustedCitation8.

bDMARD switching has become common in practice due to availability of more bDMARD therapies; however, patients are being switched to agents with similar MOA and efficacy, which may not provide the best outcomes for patients, thus making them potentially switch againCitation9–12. Patients who switch between bDMARD therapies have higher healthcare visits and costs associated with switchingCitation9. Prior studies have evaluated rates of switching, factors and reasons associated with switching, RA-related healthcare resource use and costs; however, no study has evaluated all these outcomes using a patient population within an integrated closed managed care healthcare system. In this study, we also created a descriptive table of the switcher cohort to evaluate patient characteristics between the different categories of reasons, which have not been shown in prior studies, thus providing a better overview and understanding for the switcher cohort. The objectives of this study were to identify how many RA patients newly initiated on bDMARD therapy switch to another bDMARD during the first year of therapy; to evaluate the factors and reasons associated with switching; and to compare the RA-related healthcare resource utilization and costs between bDMARD switchers and non-switchers within an integrated healthcare delivery system.

Materials and methods

Study setting and data

Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) is an integrated healthcare delivery system with ∼4 million members located in Southern California. Data were derived from the KPSC administrative database which included patient demographics, diagnoses, prescriptions, laboratory results, medical, and hospital encounters. KPSC has an electronic health medical record system which allows for more detailed information to be accessed, such as chart notes for patients. The KPSC membership currently represents 15% of the population in the Southern California region, and this membership closely mirrors the Southern California population; it is racially diverse and includes the entire socioeconomic spectrumCitation13,Citation14. The institutional review board for KPSC approved this study and all data was de-identified.

Design and study population

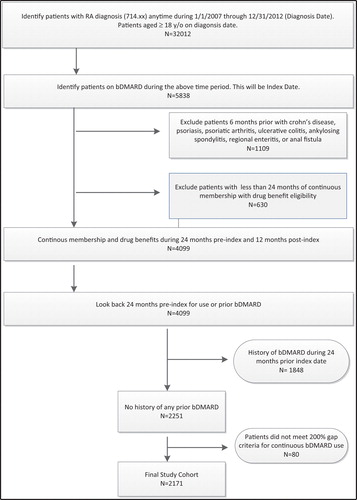

A retrospective database cohort study was conducted with the study time period of January 1, 2005 to December 31, 2013. Patients had to be ≥18 years of age with a diagnosis of RA (ICD-9 714.xx) anytime during the identification time period of January 1, 2007 to December 31, 2012 (). The index date was defined as the date of the first bDMARD prescription claim identified during the study time period. Patients had continuous membership eligibility with drug benefit 24 months prior to index date, which was labeled as the pre-index period. Patients had to have no prior history of bDMARD during the 24 months prior index date. Baseline characteristics were identified during 6 months prior to the index date and patients had 12 months of follow-up, which was labeled as the post-index period. Baseline characteristics included age, gender, body mass index, race, insurance type, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score, selected co-morbid conditions, concomitant medications, and prior healthcare visits. The CCI was measured using the Quan-Charlson comorbidity indexCitation15. The CCI score has been used in prior RA studies to evaluate severity of health for the study cohortsCitation7,Citation9. The CCI score was also used since we did not have access to any RA-specific scores such Disease Activity Score (DAS), Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) or the Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data (RAPID) score.

Newly-initiated bDMARD patients were defined as patients with no prior history of any bDMARD use during the 24 months pre-index period. Since bDMARDs have multiple indications, we focused on patients with RA, thus we excluded patients for any of the following diagnoses during the pre-index period: Crohn’s disease, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ulcerative colitis, ankylosing spondylitis, regional enteritis, or anal fistula. Patients were also excluded if they had <7 days’ supply of adalimumab or etanercept because patients should not be on <7 days therapy to experience any effect of the drugCitation9. A 200% gap criteria using days’ supply for each dispensed prescription was applied to evaluate if patients were either continuously on their current bDMARD or if a different bDMARD was initiated (indicating a switch) or if the current bDMARD was discontinued. For example, a patient who initiated first-line etanercept and had a subsequent claim for adalimumab within 60 days (i.e. within 200% gap in days’ supply) of their last etanercept claim would be considered a switcher. If this patient did not have any claim for a subsequent bDMARD within 60 days, then this was considered a discontinuation. If the patient re-started their previous bMDARD beyond the 60 days, then this was beyond the time gap of 60 days. The 200% gap criteria was followed from a prior study conducted by Meissner et al.Citation9. If patients did not meet the 200% gap criteria, they were excluded from the analysis; for example, patients who discontinued, switched, or re-started their previous bDMARD beyond the 200% gap were excluded. This bDMARD switch definition ensures the cohort was consistently on a bDMARD without a large gap in therapy ().

Outcomes of interest

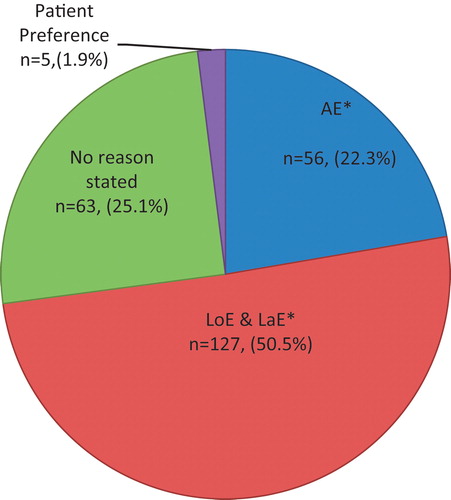

The primary outcome was to identify the percentage of patients who switch to another bDMARD during 12 months post-index. Patients were further categorized into a switch group (patients who switched to another bDMARD) and a non-switch group (patients who continued on their index bDMARD). Secondary outcomes evaluated factors and reasons associated with patients switching. We identified reasons for switching by reviewing chart notes 30 days prior and 30 days post-bDMARD switch. Using prior literature and clinical expert opinion, we categorized reasons into adverse events (AE), loss of efficacy/lack of efficacy (LoE/LaE), no reason stated, or patient preference. Lastly, we evaluated the RA-related HCRU and costs which were calculated for 12 months post-index for both groups. Visits related to RA were identified using primary and secondary discharge position with diagnosis codes of 714.xx. Costs were computed as the total of plan paid plus patient paid amount, presented at constant 2013 US dollars from a payer perspectiveCitation16,Citation17. In this study we evaluated costs related to outpatient visits, ER visits, and hospitalizations for RA-related visits. We computed costs for each RA visit, and calculated the total costs for outpatient, ER, and hospital visits. The KPSC 2013 sample charge amounts were used for hospital staysCitation16. KPSC 2013 sample fee schedules were used for various outpatient and ER visitsCitation17.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to assess baseline differences between the patient groups by using a two-sided t-test for continuous variables, and tests of proportions were used to compare distributions for categorical variables. The Wilcoxin rank-sum test was used to compare the number of hospitalizations, hospital days, ER visits, and outpatient office visits between the bDMARD switchers and non-switchers. A forward stepwise selection multivariable logistic regression model was used to evaluate factors associated with bDMARD switchers vs non-switchers. Factors including age, sex, race, selected co-morbid conditions, CCI score, concomitant medications, prior healthcare resource visits, index bDMARD therapy, and other conventional DMARD medications were controlled for in the model. Healthcare cost data are typically non-normally distributed with a skew towards the right. Therefore, we used a generalized linear model (GLM) with gamma distribution and log link function controlling for age, gender, insurance, comorbidity score, concomitant medications, and prior visits. Percentages were calculated for the various identified reasons. Lastly, we created a descriptive table of the switcher cohort to evaluate patient characteristics between the different categories of reasons. All data was analyzed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). P-values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

The initial population included 32 012 patients with a diagnosis of RA and ≥ 18 years of age. After applying additional selection criteria, the final study cohort consisted of 2171 RA patients newly initiated on a bDMARD (). The majority of the patients were initiated on etanercept (∼76%) or adalimumab (23%), and the mean number of days to switch to a different bMARD was 110 days ± 95.5 days (Supplementary Appendix Table A). There were 251 patients (12%) who switched from their index bDMARD to different bDMARD during follow-up (): 52 patients switched to adalimumab, three patients switched to anakinra, 194 patients switched to etanercept, and two patients switched to golimumab (Supplementary Appendix Table A). Since etanercept and adalimumab are anti-TNF agents, we saw that patients were being switched from anti-TNF agent to another anti-TNF agent (data not shown). For example, 179 patients (92%) who were initiated on etanercept switched to adalimumab, and 46 patients (88%) who initiated adalimumab were switched to etanercept. Out of the three patients who switched from anakinra, two patients switched to etanercept and one patient switched to adalimumab; and of the two patients who switched from golimumab, one switched to etanercept and one patient switched to adalimumab. The differences between the baseline characteristics included non-switchers having a higher CCI score (2.19 ± 2.4 vs 1.80 ± 2.2, p-value = 0.0065) vs switchers (). Even though prescriptions of NSAIDS were dispensed 100% for both groups during the baseline period, there was more use of corticosteroids and narcotics for the switcher group vs non-switcher group (). During the 6 month pre-index period, a higher percentage of switchers utilized the emergency room and had more outpatient visits compared to non-switchers (p-value <0.05). A higher percentage of non-switchers utilized the hospital more compared to switchers during the 6-month pre-index period (p-value <0.05). Statistically significant factors more likely associated with bDMARD switchers included female gender (OR = 1.48, CI = 1.02–1.86); obese weight (OR = 1.51, CI = 1.04–2.19); prior corticosteroid use (OR = 1.64, CI = 1.21–2.24); use of etanercept as an initial bDMARD (OR = 1.71, CI = 1.07–1.98); and others such as: other conventional DMARDs, prior emergency and any medical outpatient visits (). Reasons for switching included LaE/LoE (∼51%); no reason stated (∼25%); AE (∼22%), and patient preference (∼2%) (, Supplementary Appendix Table C). The baseline characteristics of patients whose switch was associated with LaE/LoE had higher rates of being overweight, with more comorbidities, along with higher use of narcotics, diabetic, lipid, and hypertension medications (Supplementary Appendix Table D). The total mean HCRY and unadjusted RA related costs for 12 months post index are shown in Table B (Supplementary Appendix Table B). presents the results of the GLM regression of mean total RA costs during the 12 month post-index period while controlling for baseline characteristics. Patients who switched to a different bDMARD had mean total RA related costs that were 25% higher compared to patients who did not switch (p-value = 0.0458). The adjusted mean RA-related costs were highly influenced by other baseline covariates such as female gender, prior use of corticosteroids, or prior use of narcotics ().

Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics for newly-initiated bDMARD users (non-experienced population).

Table 2. Factors associated with bDMARD switchers vs non-switchers.

Table 3. Gamma regression model of mean total RA-related 12 month costs.

Discussion

This is the first study to evaluate all of the following within a RA population newly initiated on a bDMARD within an integrated managed care healthcare system: (1) the proportion of RA patients switching from initial bDMARD therapy to a different bDMARD; (2) factors associated with patient switching; (3) reasons for patient switching through review of chart notes; and (4) the RA related healthcare resource utilization and costs. In this study, the patients who switched had lower CCI score vs the non-switcher group; however, had higher baseline healthcare encounters (ER visits and number of outpatient visits); utilized more corticosteroids and narcotics. In contrast, patients who did not switch had higher CCI score, more patients had hospital visits and longer mean length of stay during their prior hospitalizations. The bDMARD switchers had a healthier status compared to the non-switchers, which is similar to previous findings; however, was found to be not statistically significantCitation7,Citation9. The bDMARD switch rate of 12% in this study was higher than the Meissner et al.Citation9 finding of 7.8%; this could be due to the population differences, since Meissner et al. used a commercial database. Bonafede et al.Citation18 examined treatment patterns in the first year after initiating anti-TNF agents in a commercial database, and found that 13%, 12%, and 13% of etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximab patients, respectively, switched to another bDMARD within 1 yearCitation18; however, the rate of switch in the Bonafede et al. study includes patients with RA, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or ankylosing spondylitis, thus their overall rate of switch maybe inflatedCitation18. Another retrospective study conducted by Ogale et al.Citation7 found 12% of patients on etanercept switching to another therapy and 15.4% of patients on adalimumab switching to another therapy during their 1-year follow-up, regardless of gaps in days’ supply during follow-up. Overall, when switch rates are combined, their switch rate is higher, possibly due to our switch definitions being different. A recent study conducted by Harnett et al.Citation19 identified 15.4% as switchers, and the switchers also had the highest 12-month unadjusted mean all-cause costs vs continuers. Our study had similar findings for the switcher group.

There are many different bDMARD therapies available for clinicians to use for RA patients, and switching between the bDMARD therapies is common in real world practiceCitation9–11. Similar to a prior studyCitation12, we found that the majority of patients who switched went to another anti-TNF agent, also referred to as TNF cycling. The most common switches were between etanercept and adalimumabCitation12, which was seen in this study as well. Previous studies indicate that changes in therapy (discontinuation, switching) are often attributable to inefficacy or adverse eventsCitation7,Citation20–22. The majority of patients in this study who switched therapies were due to lack or loss of efficacy (50.5%). This was followed by adverse events (22.3%). Some of the reasons found due to lack of efficacy included active joint pain, non-response to treatment, lack of benefit, continued pain, and worsening symptoms. The results in this study are consistent with prior studies and found Lae/LoE and adverse events to be primary reasons for switching; however, there was no reason stated for 25% of patients who switched bDMARD. There is evidence to suggest that patients who have a lack or loss of efficacy to an anti-TNF agent are less likely to respond to a second anti-TNF agentCitation9,Citation20,Citation23. This indicates that the mechanism of action (MOA) may play an important role in response and, consequently, adherence to the bDMARD that a patient is switched to. There are also some studies which support the theory that switching between anti-TNF agents may be effective; however, the effectiveness of the switch bDMARD may depend on the reason for failure of the previous anti-TNF agentCitation9,Citation17,Citation23–25. Additionally this study assessed descriptive characteristics of the switcher cohort by reason. It observed that, in the majority of switchers who cited either lack/loss of efficacy or adverse event as a reason for switch, that more of those patients have comorbidities such as diabetes and hypertension along with BMI > 30. Understanding what effect these type of overlapping comorbidities has on this patient population requires additional research.

In this study, bDMARD switchers compared to non-switchers were associated with a 25% increase in post-index mean total RA related cost. Our percentage is lower than the 51% found by other studiesCitation9, which was potentially due to the inclusion of bDMARD costs. Drug costs were not included in this study. Higher RA-related outpatient visits and hospitalizations may be possible due to increased physician visits needed when switching to a new medication or adverse events. Treatment should be aimed at reaching a target of remission or low disease activity in every patient. Professional RA organizations such as the 2013 EULAR guidelinesCitation8 recommend frequent monitoring in active disease (1–3 months); if there is no improvement by at most 3 months after the start of treatment or the target has not been reached by 6 months, therapy should be adjusted. In this study, the mean time for a RA patient to switch to another bDMARD was a mean of 110 days ±99.5 days, which is in alignment with the 2013 EULAR guidelines. Prior real-world studiesCitation9,Citation12 have shown time to switch bDMARD is associated with longer time intervals ∼171 days or ∼183 days.

Limitations

As with other retrospective database studies, there are some limitations to this study. Recognizing the diagnostic uncertainty with reliance on administrative data, we attempted to limit misclassification bias by requiring a RA diagnosis, incident bDMARD dispensing, and exclusion of other potential reasons for bDMARD use. RA severity could not be addressed in our analysis, limiting understanding of differential case mix among patients. The majority of the RA patients were initiated on etanercept, thus there is not a well distribution of various initial bDMARD utilization; this could be due to formulary availability during the study time period. The RA-related costs could be under-estimated due to using fee schedules related to visit cost, and not adding other considerations such as x-rays, labs, and other tests which incur more costs. We also used the primary and secondary discharge positions to identify if the visit was RA-related; however, physicians may have labeled RA-related visits with other codes associated to adverse events from therapy. We followed patients to their first switch, and did not continue to see if patients had additional switches to help understand trending utilization patterns. Lastly, this study represents a RA cohort from an integrated healthcare delivery system, thus the relative importance of different factors represented in our models may not universally apply to other healthcare systems.

Conclusion

The findings from this study help to identify patients who are more likely to switch to another bDMARD during their 1 year of follow-up. The reasons of LoE/LaE and adverse events are identified using electronic chart notes in this study. The economic burden related to switching within the RA population is significant, and the average time to switch of ∼110 days is shorter than reported in prior studies. The majority of patients switched from an anti-TNF agent and were started on another anti-TNF. Given that there are a number of bDMARD agents, clinicians have many different agents to select from with different mechanisms of action to help manage their patients.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was supported by a research grant provided by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

GA Jr, CP, and AN were employees of Bristol-Myers Squibb when the study was conducted. NR, KJL, and VG do not have any other financial interests or potential conflict of interest with regard to the work. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Chengyi Zheng, KPSC Research & Evaluation Department, for his initial pull of chart notes for the RA study population.

References

- http://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/basics/rheumatoid.htm. Accessed September 4, 2015

- Brooks PM. The burden of musculoskeletal disease–a global perspective. Clin Rheumatol 2006;25:778-81

- Silman AJ, Hochberg MC. Epidemiology of the rheumatic diseases, 2nd edn. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001

- Sacks JJ, Luo YH, Helmick CG. Prevalence of specific types of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the ambulatory health care system in the United States, 2001-2005. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62:460-4

- Saag K, Teng GG, Patkar NM, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum (Arthritis Care Res) 2008;59:762-84

- Singh JA, Furst D, Bharat A, et al. 2012 Update of the 2008 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic agents in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2012;64:625-39

- Ogale S, Hitraya E, Henk HJ. Patterns of biologic agent utilization among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2011;12:204

- Smolen JS, Landewe R, Breedveld, FC. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2013 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73(3):492–509

- Meissner B, Trivedi D, You M, et al. Switching of biologic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in a real world setting. J Med Econ 2014;17(4):259–65

- Zhang J, Shan Y, Reed G, et al. Thresholds in disease activity for switching biologics in rheumatoid arthritis patients: experience from a large US cohort. Arth Care Res 2011;63:1672-9

- Van Vollenhoven RF. Switching between anti-tumour necrosis factors: trying to get a handle on a complex issue. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:849-51

- Oei HB, Hooker RS, Cipher DJ, et al. High rates of stopping or switching biological medications in veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2009;27:926-34

- Koebnick C, Langer-Gould AM, Gould MK, et al. Sociodemographic characteristics of members of a large, integrated health care system: comparison with US Census Bureau data. Perm J 2012;16:37-41

- Derose SF, Contreras R, Coleman KJ, et al. Race and ethnicity data quality and imputation using U.S. Census Data in an integrated health system: The Kaiser Permanente Southern California Experience. Med Care Res Rev 2013;70(3):330–45

- Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 2005;43:1130-9

- Kaiser Permanente. 2013 charge master list. 2013. http://xnet.kp.org/hospitalcharges/downloads/2013_CDM.pdf. Accessed February 11, 2014.

- Kaiser Permanente. 2013 sample fee list for Southern California. 2013. https://www.google.com/#q=kaiser+sample+fee+list+southern+california. Accessed February 11, 2014. (available upon reguest)

- Bonafede M, Fox KM, Johnson BH, et al. Factors associated with the initiation of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis: a retrospective claims database study. Clin Therapeut 2012;34:457-67

- Harnett J, Wiederkehr D, Gerber R, et al. Real-world evaluation of TNF-inhibitor utilization in rheumatoid arthritis. J Med Econ 2015;27:1-12

- Hyrich KL, Lunt M, Watson KD, et al; British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Outcomes after switching from one anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha agent to a second anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha agent in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from a large UK national cohort study. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:13-20

- Karlsson JA, Kristensen LE, Kapetanovic MC, et al. Treatment response to a second or third TNF-inhibitor in RA: resultsfrom the South Swedish Arthritis Treatment Group Register. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:507-13

- Finckh A, Simard JF, Gabay C, et al. Evidence for differential acquired drug resistance to anti-tumour necrosis factor agents in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:746-52

- Bombardieri S, Ruiz AA, Fardellone P, et al; Research in Active Rheumatoid Arthritis (ReAct) Study Group. Effectiveness of adalimumab for rheumatoid arthritis in patients with a history of TNF-antagonist therapy in clinical practice. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:1191-9

- Gomez-Reino JJ, Carmona L; BIOBADASER Group. Switching TNF antagonists in patients with chronic arthritis: an observational study of 488 patients over a four-year period. Arthritis Res Ther 2006;8:R29

- Atzeni F, Sarzi-Puttini P, Gorla R, et al. Switching rheumatoid arthritis treatments: an update. Autoimmun Rev 2011;10:397-403