Abstract

Background Population aging brings up a number of health issues, one of which is an increased incidence of herpes zoster (HZ) and its complication, post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN). Zostavax vaccine has recently become available to prevent HZ and PHN. This study evaluates the cost-effectiveness of vaccination against HZ in Spain considering a vaccination of the population aged 50 years and older and comparing this to the current situation where no vaccination is being administered.

Methods An existing, validated, and published economic model was adapted to Spain using relevant local input parameters and costs from 2013.

Results Vaccinating 30% of the Spanish population aged 50 years and older resulted in €16,577/QALY gained, €2025/HZ case avoided, and €5594/PHN case avoided under the third-party payer perspective. From a societal perspective, the ICERs increased by 6%, due to the higher price of the vaccine. The number needed to vaccinate to prevent one case was 20 for HZ, and 63 for PHN3. Sensitivity analyses showed that the model was most sensitive to the HZ and PHN epidemiological data, the health state utilities values, and vaccine price used.

Conclusion Considering an acceptable range of cost-effectiveness of €30,000–€50,000 per QALY gained, vaccination of the 50+ population in Spain against HZ with a new vaccine, Zostavax, is cost-effective and makes good use of the valuable healthcare budget.

Introduction

Herpes Zoster (HZ) is caused by the reactivation of the Varicella Zoster virus which lies dormant in individuals previously infected with the virus usually during childhood, as chickenpox. The main symptoms caused by this reactivation include rash and severe pain, which in most cases takes ∼1–2 monthsCitation1. In 20–50% of the cases it leads to complications and especially Post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN), where the initial neuropathic pain associated with HZ does not subside and continues for months or yearsCitation2–7.

Age is the main risk factor for developing HZ, with two thirds of the cases occurring in people older than 50 yearsCitation8,Citation9. Age is also a risk factor for PHN and, therefore, the number of individuals expected to develop PHN is estimated to increase over time due to the demographic changes in Europe, Canada, and the US. The risk increases sharply after the age of 50–60 years and reaches up to 50% in individuals aged 85 and older who developed HZCitation9,Citation10.

Other risk factors include diabetes, depression, psychological stress, and the use of immunosuppressive drug treatments. With more than 1.7 million people affected each year in Europe, HZ is a quite common diseaseCitation11. The incidence of HZ is two-to-five cases per 1000 per year in Europe, Canada, and the US, and one in four people will develop HZ over their lifetimeCitation9.

As of today, treatments of HZ and PHN are mainly symptomatic. They may include a combination of antivirals, various analgesics, opioids, antidepressants and sometimes anticonvulsants, and require a stepwise, personalized treatment algorithmCitation12. Efficacy is only limited in most of the patientsCitation13.

Vaccinations have been shown as representing very important advances in medicine due to their preventative nature against illnesses such as polio, meningitis, diphtheria, and tetanus. In recent years, due to the changes in demography and lifestyle choices, healthcare budgets have become increasingly under pressure and decision-makers are seeking to understand whether new treatments provide value for money. Seniors have a lower likelihood of complete recovery from infectious diseases, which may lead to a cascade of events that gradually reduces the quality-of-life, or lead to dependency on family or the healthcare system. A public health and social priority is, therefore, to keep people as healthy as possible, and preventive measures constitute a pillar in strategies toward this end. This is particularly important in Spain, where the population is ageing. In 2014, 18.2% of the Spanish population was aged over 65 years old, and this percentage will rise up to 24.9% in 2029 according to a forecast from the National Institute of Statistic (Instituto Nacional de Estadistica)Citation14. A vaccine was approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in 2006, Zostavax, that is indicated for the prevention of HZ and PHN in individuals aged 50 and olderCitation15. By increasing the specific cellular immunity against Varicella Zoster, Zostavax reduces the re-activation of the latent virus, thus reducing HZ and its complication in the form of PHN. It has been shown to significantly reduce both the incidence and severity of HZ and PHN, both in clinical studies and real-life setting, as vaccinated patients who contracted HZ experienced a milder form of the disease, and the number of HZ cases with severe and long lasting pain was significantly reducedCitation16–20.

Currently, there is no recommendation for HZ vaccination in Spain, but only a regional pilot program recently started in Castilla-Leon targeting people aged 60–64 years old with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCitation21.

This article presents the economic evidence for Zostavax in the vaccination of individuals aged 50 and older in Spain.

Methods

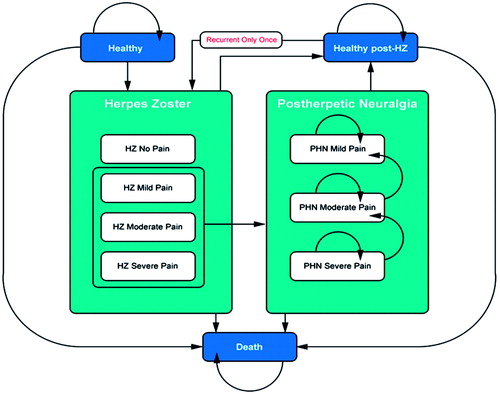

An existing economic model, described in detail in previous publications, was adapted to the Spanish settingCitation22–24. The model was developed in Microsoft Office Excel 2013. Using a Markov process shown in , the incidence of HZ and PHN was modeled in the Spanish population aged 50 and older. The model population was stratified into 5-year age bands (e.g., 50–54, 55–59, etc.), and analyzed sequentially. The model uses a 1-month cycle length, after which patients can transit to one of the 10 health states of the model: healthy, HZ (with no, mild, moderate, or severe pain), healthy post-HZ, PHN (with mild, moderate, or severe pain), and death. Recurrent HZ and the subsequent neuropathic pain are also allowed states, but are constrained to a one-time only recurrent episode. These transitions were ruled by a matrix of probability values. The model starts with all patients in the healthy state (i.e., without HZ and/or PHN) and ends when all patients have died. Two Markov traces are computed, one for the vaccinated population and one for the non-vaccinated population.

The model provides results for two possible perspectives: that of the Spanish national healthcare system, where the focus is on direct medical costs (primary and secondary care, hospitalization, medication, and vaccination costs), and a societal perspective which also includes productivity losses and patients’ co-payment. The model provides a range of outcomes, including number of cases of HZ and PHN avoided, quality-adjusted life years saved (QALYs) and number needed to vaccinate (NNV) to avoid one case of HZ/PHN. Different definitions exist, but usually PHN is defined as pain persisting after 1 month or 3 months of rash onset; this analysis only presents the results for the PHN 1-month definitionCitation3,Citation25,Citation26.

The model analyses are performed over a lifetime. Costs and benefits are discounted at 3%, which is recommended by the French College of Health Economists (CES) and the proposed guidelines for economic evaluations in Spain by López Bastida et al.Citation27,Citation28, due to the absence of official Spanish guidelines on this matter. As the choice of discount rate is especially important for preventative health programs such as vaccinations, other discount rates were tested in sensitivity analyses.

Internal validation of the model was performed in comparing the incidence of HZ and PHN observed in the model to those observed in the 3-year clinical trialCitation17 in both the vaccine and placebo arm, which matched perfectly: 315 HZ cases in the vaccine arm vs 642 in the placebo arm, and 27 PHN cases in the vaccine arm vs 80 among the placebo arm. The model’s structure was validated by an expert health economist and a European panel of experts. The assumptions specific to the Spanish model were reviewed and validated by Spanish experts.

To obtain valid estimates for HZ incidence in Spain, we identified several sources documenting the incidence for HZ in the various regions of Spain: data from the Sentinel Physician Network of Madrid (Red de Médicos Centinela de la Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid), obtained between 2007–2010, and data from a retrospective study carried out in the community of Valencia (collecting data from ambulatory care of the Valencia Health Agency of Abucasis (SIA-GAIA)) from the same period. Data from these two sources were averaged by age group to yield the data shown in Citation29,Citation30. The obtained results are in line with those reported in the systematic literature review on HZ incidence across Europe conducted by Pinchinat et al.Citation11 in 2013. A recurrence rate for HZ of 0% was used in this model, based on Spanish data, although international data have shown that recurrence is rare but possibleCitation2,Citation31. We assumed a HZ-associated mortality at 0% for the base case, but tested this parameter in sensitivity analyses with two alternative values reported in the literatureCitation32,Citation33. A European systematic literature review published in 2015 on HZ-associated mortality showed that HZ-associated mortality was low, but increased with ageCitation34.

Local clinical evidence on estimates for the percentage of patients developing PHN after having developed HZ was scarce until recently. One study from 2011 prospectively analyzed the burden of HZ and PHN and their associated costs in patients from 25 general practices in the Autonomous Community of ValenciaCitation2. This study provided the proportion of patients having persisting pain subsequent to HZ after 1 month and after 3 months for different age groups: <50, 50–59, 60–69, and > 70 years old. However, the proportion of PHN at 1 month was higher than the figures reported in previous retrospective studies in Europe. In the base case analysis, we decided to use the retrospective study EPIZOD (Etude Epidémiologique du zona et des douleurs postzosteriennes) conducted in France from the medical files of patients with HZ, based on a random sample of GPs, dermatologists, neurologists, and physicians in pain clinicsCitation35. Among the 777 cases of diagnosed HZ, 343 were considered as PHN 1 month after the initial diagnosis.

Another study from 2012 presented different results, but this time from a retrospective analysis of patient records from six medical centers and one hospital in Barcelona, providing the cumulative incidence of PHNCitation36. The heterogeneity among the published evidence led to the conduction of several sensitivity analyses to account for the uncertainty around this parameter.

For the calculation of utilities, data from the Health Survey for England (1996–1997) were used for the baseline age and gender-specific utilities as no data were available for Spain, and the UK was assumed to have similar population characteristicsCitation37. Since the data from this study is provided in 10-year age cohorts, data from the Canadian National Population Health Survey (1996–1997) were used to obtain data for the 5-year age cohorts used in the economic model. To reflect the utility specific to HZ and PHN, decrements were applied to the age and gender-specific utilities, as shown in using values from the Oster et al.Citation38 study where disease-specific utilities were estimated using EQ-5D in a large PHN population (n = 385) in real life conditions. As PHN and HZ pain are both neuropathic in nature, it was assumed that the utility associated with the different levels of pain severity will not vary between the two health statesCitation38.

Table 1. Input parameters and values for the base case analysis of the Spanish VZV model.

Clinical data on the vaccine Zostavax were obtained from the two pivotal studies. The first is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, the Shingles Prevention Study (SPS) involving 38 546 immuno-competent adults aged ≥60 years followed-up for a median time of 3.1 years, where Zostavax significantly reduced the incidence of HZ (overall by 51%; individuals aged 60–69: 64%; individuals aged 70–79: 41%; ≥80: 18%) and PHN (overall: 39%; individuals aged 60–69: 5%; 70–79: 55% ≥80: 26%), while also reducing the severity of HZCitation17. Furthermore, the number of HZ cases with severe and long lasting pain was significantly reducedCitation17. The second is the Zostavax Efficacy and Safety Trial (ZEST), which included 22,439 subjects aged 50–59 years and had a median follow-up of 1.3 years, and showed a significant reduction in the incidence of HZ by 69.8%Citation19. In addition, follow-up studies of the SPS trial (STPS and LTPS) demonstrated that vaccine efficacy persists up to 10 years, although protection decreases gradually over time and with increasing patient age. The Short-Term Persistence Study (STPS) provided additional efficacy data up to 7 years and the Long-Term Persistence study (LTPS) that was conducted on a sub-group of subjects of the pivotal efficacy study SPS provided data up to 11 years after vaccinationCitation39,Citation40.

The model includes the effect of the vaccination as relative risk reduction of HZ in healthy individuals and PHN in HZ patientsCitation17. The number of PHN cases is also indirectly impacted with the reduction of the number of HZ cases, as this is a prerequisite for developing PHN. Furthermore, the model reflects vaccination impact on the duration of PHNCitation17.

The model reflected the age-specific efficacy and its persistence, but waning over time, based on efficacy persistence dataCitation17,Citation19. This has been taken into account in the model, using a combination of two Poisson regression models using data from the ZEST, SPS, and STPS trials previously published and used in another adaptation of this cost-effectiveness model. In the absence of persistence data for vaccine efficacy against PHN, vaccine protection against PHN was assumed to last 10 years. Sensitivity analyses were carried out using fixed waning rates and other vaccine duration assumptionCitation7,Citation9,Citation33,Citation41.

Cost inputs were retrieved from Cebrián-Cuenca et al.Citation2 and inflated to €2013. It was considered that the vaccine was administered by a nurse after a prescription from a physician. Therefore, vaccine administration cost was estimated by the time dedication of the medical staff (6 min for the physician and 7 min for the nurse assessed by a panel of experts) and their hourly wage (obtained from a national database of healthcare costs, eSalud)Citation42. Vaccine price corresponds to the pharmaceutical company sale price. Vaccination coverage rate was assumed at 30% for the base case and was also tested in sensitivity analysis as the value of the parameter was uncertain. Hospitalization costs were obtained from Registro de altas of the Spanish health Ministry (CIE9 MC – CMBD 2010)Citation43.

All other input parameters are included in .

Sensitivity analyses

A number of sensitivity analyses were performed to investigate the effect of parameters uncertainties on the results. We carried out both deterministic sensitivity analyses where one parameter is changed at a time while all others are held constantly, and probabilistic sensitivity analyses, where parameter values of most parameters are randomly drawn from distributions obtained for each of the parameters considered. The following deterministic sensitivity analyses were considered (see ).

Table 2. Values used for sensitivity analyses.

Probabilistic sensitivity analyses were performed using Monte Carlo simulations on key model parameters; HZ incidence and PHN proportions were assumed to follow a beta distribution, HZ/PHN outpatient care costs were tested using a Gamma distribution, and HZ/PHN utilities were also varied using a Beta distribution. The model was run 1000 times, with different sets of inputs drawn randomly from those pre-specified distributions, and the results of the iterations were computed on a cost-effectiveness plane.

Results

Base case analysis

As shown in , the model predicts that vaccinating 30% of people aged 50 years or older in Spain would results in 244 046 fewer cases of HZ, 88 359 fewer of PHN, and in a gain of 29,819 QALYs. As shown in , the corresponding incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was €16 577€/QALY gained compared to a no vaccination policy from the TPP perspective. From a societal perspective the ICER increased to €24 189 €/QALY gained. The cost per HZ case avoided was €2025 from the TPP perspective and €2955 from the societal perspective. The cost per PHN cases avoided reached €5594 from the TPP perspective and €8163from the societal perspective. From both perspectives, 20 people need to be vaccinated to avoid one case of HZ, while 56 people need to be vaccinated to avoid one case of PHN3.

Table 3. Base case (lifetime horizon).

Table 4. ICER from TPP and societal perspective (lifetime horizon).

Sub-group analyses

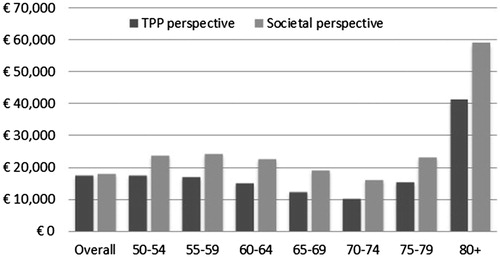

Sub-group analyses were conducted for each 5-years age-group from 50 years old. As shown in , ICER remained below the €30,000/QALY gained for the age groups from 50–54 to 75–79 years old. The group 70–74 was the most effective group to vaccinate, with an ICER at €10,382/QALYs gained from the TPP perspective and €16,296/QALYs gained from the societal perspective. The vaccination was least effective for the 80+ age group, with ICERs exceeding €40,000, due to the decreased vaccine protection and increased mortality.

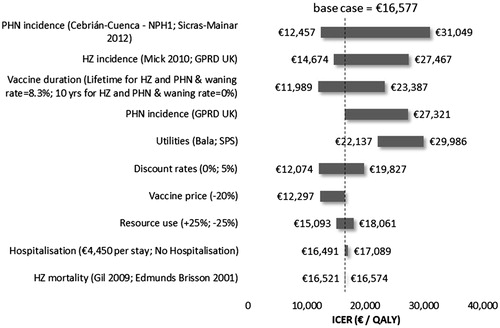

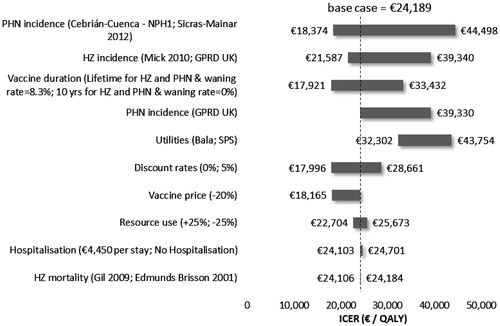

Sensitivity analyses

The tornado diagrams in from the TPP perspective and in from the societal perspective illustrate ICERS difference from the base case for a series of sensitivity analyses performed for the Spanish population aged 50 or older. Variables with the most significant impact on the ICER were the HZ incidence and PHN proportion, the duration of vaccine protection, the vaccine price, and the utilities. Applying a lower proportion of people affected by PHN, estimated by Sicras-Mainar et al.Citation36, resulted in an increase in the ICERs to €31,049/QALYs from a TPP perspective and to €44,498 from a societal perspective.

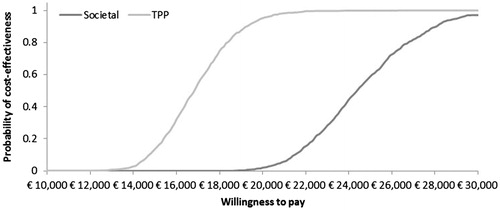

Probabilistic sensitivity analysis showed that the cost-effectiveness of the vaccination program in the 50+ age group was maintained across the simulations. The cost-effectiveness acceptability curves derived from these analyses show probabilities of 100% and 97.1% for the ICERs to remain below the €30,000 threshold for the TPP and societal perspectives, respectively ().

Discussion

Considering an acceptable range of cost-effectiveness of €30,000–€50,000 per QALY gained,1 the investigated vaccination strategy against HZ of all individuals aged 50 and older in Spain would be considered as a cost-effective option compared to the situation of no vaccination. Assuming a 30% coverage rate, this would involve an upfront investment of €16,577 per additional QALY gained, while 244,046 episodes of HZ and 88,359 cases of PHN (3-month definition) would be avoided, alleviating the burden of zoster in Spain. An episode of herpes zoster can lead to the decompensation of one or several organic functions in fragile person when associated with pain and poly-medicationCitation44. Consequences of specific locations such as zoster ophtalmicus, long lasting pain complication, or underlying disease complication can have a dramatic impact on patient and caregivers daily life and accelerate loss of autonomyCitation44–47. Preventing HZ events and its complications can, therefore, contribute to improve healthy aging of people in Spain.

Zostavax is a live-attenuated vaccine; therefore, only immunocompetent individuals can receive it. Besides the fact that Zostavax is licensed in Europe for immunization of adults over 50 years old, vaccination recommendation varies across countries on the age of vaccination. Austria was the first country to develop a specific recommendation for HZ vaccination for persons aged over 50Citation50. In France, the vaccination is recommended for people aged from 65–74 years, with a catch-up program for the 75–79 year-olds, whereas in the UK it is recommended for adults aged 70 years, with a catch up program for those aged 70–79Citation44,Citation51. A regional pilot program has recently started in Castilla-Leon targeting people aged 60–64 years old with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and may be extended gradually to other age and population groupsCitation21. Local clinical and economic evidence support the implementation of zoster vaccination in Spain. Besides, the analysis by age group showed that vaccination was the most cost-effective for the age cohort 65–74 years, which is in line with the age group recommended for the vaccination in other European countries (e.g., UK and France). Offering Zostavax in the vaccination program for elderly, along with the seasonal flu vaccination, could enable a correct implementation. Another option could be to first target the population at risk of HZ, as with the pilot program in Castilla-Leon, e.g. people aged 70 or older or people aged 60 or older with underlying conditions that increase the risk of shingles and who may face more complicated zoster and HZ management.

The result of this analysis is in line with the results of most other economic evaluations which showed the cost-effectiveness of universal HZ vaccination in adults aged 50 years or 60 years and olderCitation52–54. A systematic literature review from 2014 compared cost-effectiveness results across studies by projecting the health and economic impacts of vaccinating one million adults over a lifetime and converting costs into 2012 US dollarsCitation55. Results for studies conducted in Europe ranged from 11,000 US$(€7000) per QALY gained to 49,000 US$(€36,000) per QALY gained; the ICERs estimated in this Spanish analysis fall within this range, with corresponding values of ∼21,700 and 23,000 2012 US$per QALY gained for the societal and TPP perspectives, respectively. Six of the reviewed European studies found that vaccination was likely to be cost-effectiveCitation22,Citation23,Citation52,Citation56–58. The others were either slightly over the threshold or did not clearly state or had difficulty to conclude whether HZ vaccination was cost-effective or notCitation59–61.

Even if efficacy and safety have been confirmed in real-life, uncertainties remain on the duration of protection after 7 years, as highlighted by the WHO in its report Herpes zoster vaccinesCitation62. However, this is the case for all vaccines at the time of their appraisal. Indeed, the consideration of waning of efficacy since the time of vaccination along with the age at vaccination is crucial in estimating the cost-effectiveness of HZ vaccination. A specific interest of the present analysis is that a statistical model developed by using data from efficacy persistence studies has been used in our model to take into consideration real life waning in efficacy. Thus, compared to the majority of previous models, the waning in vaccine efficacy for HZ cases depends on the age at vaccination and time since vaccination. Another strength of the present study is the use of recent local data sources that allow producing reliable results.

However, for utility, data from other countries were used due to the lack of Spanish data. The uncertainty around the utility values represents a limit to this study. Nevertheless, this uncertainty was cautiously tested in the sensitivity analysis in which alternative values from four different published sources were evaluated. The use of other sources for utility values such as Bala and SPS Pelissier showed a great impact on ICER: at €25,729 per QALY gained from the TPP perspective with values from Bala et al.Citation63 and at €34,851 per QALY gained with values from PellissierCitation64. For both of these alternative utility values, their associated decrements were lower, resulting in a decrease of the total number of QALYs gained over the lifetime.

Results were also very sensitive to the PHN proportion. PHN is defined as pain that persists beyond the acute phase of a HZ episode, and is often assessed at 1 and 3 months after diagnosis, varying across studies. In this study we used values from the EPIZOD studyCitation35, conducted in France on almost 800 patients, which focused on the same age cohort as our study. The values used in the model were lower than Cebrián-Cuenca et al.Citation2 for the 1-month estimates, but higher than the studies conducted in the UKCitation7, and the other Spanish studyCitation36. The different study designs could explain the heterogeneity across studies, but also the definition and timing of the diagnosis. The proportions of HZ developing PHN being an uncertain parameter, several sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the impact of this uncertainty on the model outcomes.

Overall, sensitivity analyses showed that the model was robust to changes in key model parameters such as epidemiological data, utility values and vaccine efficacy, with all the simulations from the PSA falling below a reasonable cost-effectiveness threshold of €30,000.

Conclusion

This cost-effectiveness analysis concludes that a vaccination program against HZ covering 30% of the individuals aged 50 years and older in Spain could be considered as cost-effective as it falls below the reasonable cost-effectiveness threshold of €30,000 per QALY gained, with the highest benefits being realized in individuals aged 65–74, and the least in individuals aged 80 years and older.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This manuscript received funding from Sanofi Pasteur MSD.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

JLLB and MU are employees of Sanofi Pasteur MSD, which commercializes Zostavax within Spain. CG and FB have also declared sponsorship from Sanofi Pasteur MSD. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors of the manuscript warmly thank Emmanuelle Préaud, Nathalie Largeron, and Xiaoyan Lu, employees of SPMSD, for their comprehensive review of the manuscript.

Notes

1 In Spain, there is no official cost-effectiveness threshold. The WHO (World Health Organization) reported that an intervention that provided an extra year of healthy life for less than 3-times the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita is still considered reasonable value for money or quite cost-effectiveCitation48. The GDP per capita in Spain was last recorded at US$29 767.4 (€22 432) in 2014Citation49. In this context, the current analysis has assumed that healthcare interventions which range between €30 000–€50 000 per QALY are likely to be considered as cost-effective.

References

- Johnson RW. Consequences and management of pain in herpes zoster. J Infect Dis 2002;186(1 Suppl):S83-S90

- Cebrian-Cuenca AM, Diez-Domingo J, San-Martin-Rodriguez M, et al. Epidemiology and cost of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia among patients treated in primary care centres in the Valencian community of Spain. BMC Infect Dis 2011;11:302

- Helgason S, Petursson G, Gudmundsson S, et al. Prevalence of postherpetic neuralgia after a first episode of herpes zoster: prospective study with long term follow up. BMJ 2000;321:794-6

- Kost RG, Straus SE. Postherpetic neuralgia–pathogenesis, treatment, and prevention. N Engl J Med 1996;335:32-42

- Lang PJ. Herpes zoster vaccine: what are the potential benefits for the ageing and older adults? Eur Geriatr Med 2011;2:134-9

- Pica F, Gatti A, Divizia M, et al. One-year follow-up of patients with long-lasting post-herpetic neuralgia. BMC Infect Dis 2014;14:556

- Scott FT, Johnson RW, Leedham-Green M, et al. The burden of Herpes Zoster: a prospective population based study. Vaccine 2006;24:1308-14

- Johnson RW, Wasner G, Saddier P, et al. Postherpetic neuralgia: epidemiology, pathophysiology and management. Expert Rev Neurother 2007;7:1581-95

- Kimberlin DW, Whitley RJ. Varicella-zoster vaccine for the prevention of herpes zoster. N Engl J Med 2007;356:1338-43.

- Burke BL, Steele RW, Beard OW, et al. Immune responses to varicella-zoster in the aged. Arch Intern Med 1982;142:291-3

- Pinchinat S, Cebrian-Cuenca AM, Bricout H, et al. Similar herpes zoster incidence across Europe: results from a systematic literature review. BMC Infect Dis 2013;13:170

- Johnson RW, McElhaney J. Postherpetic neuralgia in the elderly. Int J Clin Pract 2009;63:1386-91

- Chen N, Li Q, Yang J, et al. Antiviral treatment for preventing postherpetic neuralgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;2:CD006866

- Proyección de la Población de España 2014-2064. Instituto Nacional de Estadística

- EPAR: Summary for the public. European Medicines Agency, 2015

- Langan SM, Smeeth L, Margolis DJ, et al. Herpes zoster vaccine effectiveness against incident herpes zoster and post-herpetic neuralgia in an older US population: a cohort study. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001420

- Oxman MN, Levin MJ, Johnson GR, et al. A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. N Engl J Med 2005;352:2271-84

- Sanford M, Keating GM. Zoster vaccine (Zostavax): a review of its use in preventing herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. Drugs Aging 2010;27:159-76

- Schmader KE, Levin MJ, Gnann JW Jr, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of herpes zoster vaccine in persons aged 50-59 years. Clin Infect Dis 2012;54:922-8

- Tseng HF, Smith N, Harpaz R, et al. Herpes zoster vaccine in older adults and the risk of subsequent herpes zoster disease. JAMA 2011;305:160-6

- Sanitaria. Unos 9.500 enfermos de EPOC iniciarán el piloto de vacunación frente al herpes zóster 2015. Redaccion Medica, Spain, 2015. http://www.redaccionmedica.com/autonomias/castilla-leon/unos-9-500-enfermos-de-epoc-iniciaran-el-piloto-de-vacunacion-frente-al-herpes-zoster-77732 Accessed May 28, 2015

- Annemans L, Bresse X, Gobbo C, et al. Health economic evaluation of a vaccine for the prevention of herpes zoster (shingles) and post-herpetic neuralgia in adults in Belgium. J Med Econ 2010;13:537-51

- Moore L, Remy V, Martin M, et al. A health economic model for evaluating a vaccine for the prevention of herpes zoster and post-herpetic neuralgia in the UK. CERA 2010;8:7

- Szucs TD, Largeron N, Dedes KJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of adding a quadrivalent HPV vaccine to the cervical cancer screening programme in Switzerland. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:1473-83

- Dworkin RH, Portenoy RK. Pain and its persistence in herpes zoster. Pain 1996;67:241-51

- Watson P. Postherpetic neuralgia. Am Fam Physician 2011;84:690-2

- Clément O, Barnay T, Le Pen C. Actualisation partielle du Guide méthodologique pour l'évaluation économique des stratégies de santé. Collège des Économistes de la Santé, France, 2011

- Lopez BJ, Oliva J, Antonanzas F, et al. [A proposed guideline for economic evaluation of health technologies]. Gac Sanit 2010;24:154-70

- Red de Médicos Centinela de la Comunidad de Madrid, años 2007 a 2010. Servicio Madrileño de Salud; Dirección General de Atencion primera; Servicio de Epidemiología, 2010

- Morant-Talamante N, Diez-Domingo J, Martínez-Úbeda S, Puig-Barberá J, Alemán-Sánchez S, Pérez-Breva L. Herpes zoster surveillance using electronic databases in the Valencian Community (Spain). BMC Infectious Diseases. 2013;13:463. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-13-463.

- Volpi A, Gatti A, Pica F. Frequency of herpes zoster recurrence. Mayo Clin Proc 2011;86:586; author reply 586-7

- Edmunds WJ, Brisson M, Rose JD. The epidemiology of herpes zoster and potential cost-effectiveness of vaccination in England and Wales. Vaccine 2001;19:3076-90

- Gil A, Gil R, Alvaro A, et al. Burden of herpes zoster requiring hospitalization in Spain during a seven-year period (1998-2004). BMC Infect Dis 2009;9:55

- Bricout H, Haugh M, Olatunde O, et al. Herpes zoster-associated mortality in Europe: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2015;15:466

- Mick G, Gallais JL, Simon F, et al. [Burden of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia: incidence, proportion, and associated costs in the French population aged 50 or over]. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique 2010;58:393-401

- Sicras-Mainar A, Navarro-Artieda R, Ibanez-Nolla J, et al. [Incidence, resource use and costs associated with postherpetic neuralgia: a population-based retrospective study]. Rev Neurol 2012;55:449-61

- Health Survery for England 1996. Crown Copyright, London, 1998. http://www.archive.official-documents.co.uk/document/doh/survey96/ehch1.htm. Accessed 2006

- Oster G, Harding G, Dukes E, et al. Pain, medication use, and health-related quality of life in older persons with postherpetic neuralgia: results from a population-based survey. J Pain 2005;6:356-63

- Morrison VA, Johnson GR, Schmader KE, et al. Long-term persistence of zoster vaccine efficacy. Clin Infect Dis 2015;60:900-9

- Schmader KE, Oxman MN, Levin MJ, et al. Persistence of the efficacy of zoster vaccine in the shingles prevention study and the short-term persistence substudy. Clin Infect Dis 2012;55:1320-8

- Chidiac C, Bruxelle J, Daures JP, et al. Characteristics of patients with herpes zoster on presentation to practitioners in France. Clin Infect Dis 2001;33:62-9

- Oblikue. Base de conocimiento de costes y precios del sector sanitario 2015. National database, Spain, 2015. http://www.oblikue.com/bddcostes/. Accessed 2015

- Registro de altas. Ministerio de Salud, 2010

- Vaccination des adultes contre le zona - Place du vaccine Zostavax®. Haut Conseil de Santé Publique

- Mortensen GL. Perceptions of herpes zoster and attitudes towards zoster vaccination among 50-65-year-old Danes. Dan Med Bull 2011;58:A4345

- Schmader K. Herpes zoster in the elderly: issues related to geriatrics. Clin Infect Dis 1999;28:736-9

- Weinke T, Glogger A, Bertrand I, et al. The societal impact of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia on patients, life partners, and children of patients in Germany. Scientific World Journal 2014;2014:749698

- Chapter 4: Reducing risks and preventing disease: population-wide interventions. World Health Organization, 2011

- GDP per capita (current US$) The world bank. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD. Accessed January 15, 2015

- Stefanoff P, Polkowska A. Varicella and Herpes Zoster surveillance and vaccination recommendations 2010–2011. 2010

- Herpes zoster (shingles) immunisation programme 2013/2014: Report for England. Public Health England, London, 2014.

- Bresse X, Annemans L, Preaud E, et al. Vaccination against herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in France: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2013;13:393-406

- Preaud E, Uhart M, Bohm K, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a vaccination program for the prevention of herpes zoster and post-herpetic neuralgia in adults aged 50 and over in Germany. Hum.Vaccin.Immunother 2015;11:884-96

- Szucs TD, Pfeil AM. A systematic review of the cost effectiveness of herpes zoster vaccination. Pharmacoeconomics 2013;31:125-36

- Kawai K, Preaud E, Baron-Papillon F, et al. Cost-effectiveness of vaccination against herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia: a critical review. Vaccine 2014;32:1645-53

- de Boer PT, Pouwels KB, Cox JM, et al. Cost-effectiveness of vaccination of the elderly against herpes zoster in The Netherlands. Vaccine 2013;31:1276-83

- Szucs TD, Kressig RW, Papageorgiou M, et al. Economic evaluation of a vaccine for the prevention of herpes zoster and post-herpetic neuralgia in older adults in Switzerland. Hum Vaccin 2011;7:749-56

- Van Hoek AJ, Gay N, Melegaro A, et al. Estimating the cost-effectiveness of vaccination against herpes zoster in England and Wales. Vaccine 2009;27(9):1454-67

- Bilcke J, Marais C, Ogunjimi B, et al. Cost-effectiveness of vaccination against herpes zoster in adults aged over 60 years in Belgium. Vaccine 2012;30:675-84

- Ultsch B, Weidemann F, Reinhold T, et al. Health economic evaluation of vaccination strategies for the prevention of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in Germany. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:359

- Van Lier A, Van Hoek AJ, Opstelten W, et al. Assessing the potential effects and cost-effectiveness of programmatic herpes zoster vaccination of elderly in the Netherlands. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:237

- Herpes zoster vaccines. SAGE Working Group on Varicella and Herpes Zoster Vaccines.

- Bala MV, Wood LL, Zarkin GA, et al. Valuing outcomes in health care: a comparison of willingness to pay and quality-adjusted life-years. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:667-76

- Pellissier JM. Evaluation of the cost-effectiveness in the United States of a vaccine to prevent Herpes Zoster and Postherpetic Neuralgia in older adults. Vaccine 2007;25:8326-37

- Gauthier A, Breuer J, Carrington D, et al. Epidemiology and cost of herpes zoster and post-herpetic neuralgia in the United Kingdom. Epidemiol Infect 2008:1-10

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. http://www.ine.es. Accessed 2014

- National Population Health Survey (NPHS) 1996-1997. Statistics Canada,

- Heintz E, Gerber-Grote A, Ghabri S, et al. Is There a European view on health economic evaluations? Results from a synopsis of methodological guidelines used in the EUnetHTA Partner Countries. Pharmacoeconomics 2016;34:59-76

- Garcia CM, Castilla J, Montes Y, et al. [Varicella and herpes zoster incidence prior to the introduction of systematic child vaccination in Navarre, 2005-2006]. An Sist Sanit Navar 2008;31:71-80

- Gater A, Abetz-Webb L, Carroll S, et al. Burden of herpes zoster in the UK: findings from the zoster quality of life (ZQOL) study. BMC Infect Dis 2014;14:402

- Serpell M, Gater A, Carroll S, et al. Burden of post-herpetic neuralgia in a sample of UK residents aged 50 years or older: findings from the Zoster Quality of Life (ZQOL) study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2014;12:92

- Guenther L. Herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia. Exp Rev Dermatol 2015;1:607-18

- Li X, Zhang JH, Betts RF, et al. Modeling the durability of ZOS- TAVAX(®) vaccine efficacy in people 60 years of age. Vaccine 2015;33:1499-505.