Abstract

Just after midnight on the 28th of September 1994, the Estonian-flagged ro-ro passenger ferry MV Estonia was shipwrecked on its route between Tallinn and Stockholm. Out of about 1000 persons on board only 137 survived. This paper describes the work that the Psychiatric Clinic at Ersta Hospital performed with the relatives of the MV Estonia victims after the disaster, in addition, we present data from seven consecutive Swedish nationwide surveys based on a questionnaire, which started as a correspondence between the hospital and the relatives of the Estonia victims. Findings concerning the care relatives received and issues regarding their collaboration with the decisionmaking authorities are presented. The importance of inviting the relatives to participate in discussions concerning the Estonia victims is stressed.

Unos minutos después de la medianoche del 28 de septiembre de 1994 el transbordador de bandera estoniana, el MV Estonia, naufragó en la ruta entre Tallinn y Estocolmo. Del total de casi 1000 personas a bordo sólo 137 sobrevivieron. Este artículo describe el trabajo que la Clinica Psiquiátrica del Hospital de Ersta Ilevó a cabo con los familiares de las víctimas del MV Estonia después de la catástrofe. Además se presentan los datos basados en siete encuestas consecutivas en que se utilizó un cuestionario distribuido en toda la nación. Este cuestionario, que fue concebido inicialmente sólo como una simple correspondencia entre el hospital y los familiares de las víctimas, permitió definir otros aspectos. a) diversos elementos relacionados con la atención que recibieron los familiares y b) diferentes temas vinculados con la participatión de los familiares en las decisiones gubernamentales. Se destaca el hecho que los familiares de las víctimas participen en las discusiones concernientes a la catástrofe del Estonia.

Un peu après minuit, le 28 septembre 1994, le navire roulier de transport de passagers MV Estonia, battant pavillon estonien, fit naufrage entre Tallinn et Stockholm. Seuls 137 des quelques 1 000 passagers ont survécu. Cet article rapporte les résultats du travail qui a été réalisé auprès des membres des familles des victimes du MV Estonia dans le service de psychiatrie de l'hôpital de Ersta à la suite de la catastrophe. Des données fondées sur les résultats d'un questionnaire national, qui leur a été adressé à sept reprises après la catastrophe, sont rapportées. Ce questionnaire, qui n'était conçu au départ que comme une simple correspondance entre l'hôpital et les membres des familles des victimes, a permis de définir plusieurs éléments concernants les soins qui leur ont été prodigués et de poser le problème en ce qui concerne leur participation aux décisions prises par le gouvernement. Cette étude a permis de souligner l'intérêt de la participation des membres des familles aux entretiens concernant les victimes de la catastrophe de l'Estonia.

The Estonia ferry disaster

On September 27, 1994, the Estonian-flagged roro passenger ferry MV Estonia departed from Tallinn, Estonia en route to Stockholm, Sweden. Just after midnight the ship capsized and sank near Utö, an island off the coast of Finland. There were about 1 000 people on board and of these, only 137 survived.Citation1 Many were left afloat in 11 °C water for around 6 to 7 hours before being rescued. Those who survived saw many fellow passengers die during the long, cold night. According to the Accident Investigation Commission, 17 countries were represented on board. Ihe majority of the passengers were Swedish (n=552). Of the 552 Swedish passengers, 51 were rescued, 40 bodies were recovered, and 461 are still missing.Citation1

Sweden had not been involved in a war for almost 200 years and had been spared from major catastrophes. Ihe sinking of the Estonia was the first major disaster in modem-day Sweden. The hospitals in the Stockholm area had received previous training in disaster emergency service that included examples of just such an incident occurring in the Baltic Sea. Now for the first time the extensive psychosocial preparations that had been made in Stockholm would be put to use in helping those affected.

The Prime Minister, who was soon to leave office, made an announcement immediately following the incident promising that no effort would be spared to try to recover the remaining bodies. For his part, two days after the disaster, the Prime Minister-elect added, during a television interview, that efforts would also be made to salvage the ship.

However, on December 15, 1994, the Swedish government decided not to salvage the MV Estonia. The decision was based on the standpoints and conclusions of the National Maritime Administration and of the Ethics Committee appointed by the government. The Ethics Committee came to the conclusion that the vessel should bc scaled and covered with concrete. On March 2, 1995, the government entrusted the National Maritime Administration to purchase the concrete and have the MV Estonia covered. The process of covering the ship was already under way when the government, on February 11, 1999, decided that the project should be discontinued.

The government decided on September 18, 1997 to appoint an Analysis Group whose responsibility would be to review the public actions that had been taken in connection with the Estonia disaster. The Analysis Group submitted a report to the government on November 12, 1998, in which they recommended that efforts should bc made to recover and identify the deceased.Citation2 On February 11, 1999 the government decided not to follow these recommendations.Citation3

The Ersta Psychiatric Clinic

The Ersta Psychiatric Clinic is specifically devoted to treating hospital personnel, its first responsibility being to hospital personnel from Stockholm County Council area. The Psychiatric Clinic is part of Ersta Hospital, which is owned by the Ersta Deaconess Society, a nonprofit association in close connection with the Church of Sweden. It has 40 employees, which makes it the smallest psychiatric clinic in Stockholm. Because Ersta does not belong to Stockholm County Council, Ersta Hospital was the only emergency hospital that had not received disaster emergency training.

What can we at Ersta do to help the victims? This question was to be often raised on the day of the catastrophe and the following days. As Ersta Hospital was not part of the emergency plan, the answer was obvious. Ersta should continue with its habitual health care activities and let the other hospitals concentrate on helping the victims. During the first days, the Psychiatric Clinic at Ersta Hospital kept on with the daily psychiatric workload as planned. However, just two days after the catastrophe, relatives of the Estonia passengers started to call. A company, many employees of which had been on board the Estonia, also called the clinic asking if we could do something to help since the crisis groups in Stockholm were being shut down. Ersta learned that 7 of the 9 hospitals in Stockholm had shut down their Estonia crisis groups because so few people had contacted them. Only the two university hospitals, Huddinge Hospital and Karolinska Hospital in Stockholm, intended to keep their crisis groups going, at least for the following two days.

The following day, Sweden's largest morning newspaper carried an article about the distraught relative of a victim who had been turned away after showing up at a crisis center in Stockholm. Ersta got in touch with the crisis centers at Huddinge and Karolinska, asking them if they were going to start groups for the relatives. We could picture what would happen when all of the crisis groups had shut down and the relatives' reactions began to multiply. After several enquiries, we learned that Huddinge and Karolinska had no intention of starting groups for relatives, leaving it up to Ersta to take the initiative.

The weeks after the Estonia disaster

The Sunday after the Estonia catastrophe, the decision was made to notify the relatives of the new crisis groups that were being set up at Ersta Hospital. An official memorial service was to be broadcast on the media throughout Sweden, and the Dean of the Church was asked to read a message to the relatives. However, instead, the message was distributed by hand to the persons attending the memorial service. The message wasn't typed very well and part of it was in longhand. We had not intended for the relatives to receive the message in that manner, especially under such tragic circumstances. But in this way, a small paragraph was published in the morning papers informing those interested that they could either call Ersta or, 1 week after the disaster, go to the clinic, where information about the crisis groups for relatives would be available. During the first couple of days, the clinic didn't receive any phone calls. However, the third day, the phones began to ring. Many callers said they would like to come and take part in the crisis groups for relatives, but expressed concern about the presence of television and newspaper reporters, asking us to guarantee that the press would not be there. Accordingly, we asked the newspapers and television networks to show understanding, and posted a note to that effect at the entrance to the clinic. Over 120 relatives attended the meeting that evening. Besides giving information on crisis groups for relatives and asking them to write down their requests, some practical post-disaster information was given by a lawyer, an insurance company representative, and the police. The entire room was like an open wound of grief, despair, and rage. A petition from some relatives to demand the salvaging of Estonia was passed around, which many signed.

Eleven crisis groups were subsequently organized, including one just for children and teenagers, and one for the relatives of survivors. During the months when the groups met regularly, group leaders met every week for guidance and supervision. More and more relatives continued to contact Ersta. In order to meet the information needs and requests, Ersta began holding open house for the relatives twice a week. Ersta also held several large meetings with invited speakers, mainly to deal with financial and legal matters as well as general issues. The relatives kept asking us to do even more to help. Although our small clinic could not handle more groups or meetings at that time, it was difficult to turn down the requests from the relatives and survivors. That is when the idea of a questionnaire came up.

The Ersta questionnaire

How the questionnaire evolved

One of the guest speakers at earlier training seminars, Dagfinn Winje, a psychologist from Norway, had used questionnaires during a major disaster in 1988.Citation4,Citation5 He explained how this had had definite therapeutic results for the participants. This questionnaire was based on two classic inventories, the Symptom Checklist (SCL-90).Citation6 and the Impact of Event Scale (IES).Citation7 The same inventories were used after a ferry accident that took place in Sweden in 1990. On the basis of these two inventories, a new questionnaire was put together at Ersta.

The questionnaire study was not intended as a research project, but as a part of Ersta's work with the relatives. The main purpose was to be of real help to them. However, when the first completed questionnaires came back, they included much more information than just answers to the structured items. Ihe relatives added personal comments, other information, and sometimes included letters describing their present situation. Many relatives living in rural areas pointed out that this was the first time anyone had asked them about how they had been feeling since the catastrophe. The questionnaire study that had started as a simple correspondence with the relatives took on far greater proportions than had been anticipated. Distribution and processing of the questionnaires started posing considerable financial problems for Ersta, the smallest psychiatric clinic in Stockholm. To date, Ersta has received funds for eight questionnaires.

This paper discusses the care the relatives received and issues regarding their collaboration with the decisionmaking authorities. Most of these items were presented as visual analog scales, with a numbered response format (ranging between 1 and 10) below. For ease of presentation, answers to the questionnaire were divided into three categories (yes, no, don't know). Moreover, only the answers from the relatives (and not from the survivors) are presented. The surveys were approved by the Ethics Committee of Huddinge Hospital.

The participants

The first questionnaire was sent out just before Christmas, 1994, ie, 3 months after the disaster. To insure that the questionnaire would not arrive without warning, Peter Nobel, a lawyer and the government-appointed representative for the Estonia victims, announced the questionnaire's arrival in a letter that was sent to the relatives. Since then, six more surveys have been conducted, 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 months after the ferry disaster.

The first four questionnaires were sent only to the relatives of the deceased and the survivors who had lost a relative in the disaster. However, the survivors who had not lost a relative expressed their frustration at being left out. So, a letter was written to all survivors irrespective of whether or not they had lost a relative, asking if they wished to participate in the survey. The answer being yes, the survivors were included starting with the fifth questionnaire.

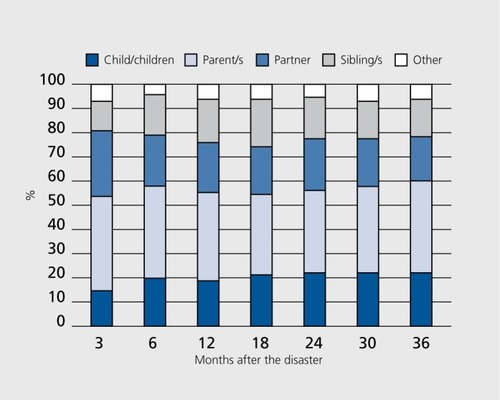

To date, 879 relatives have completed the questionnaires, representing 89% of the MV Estonia's Swedish victims. The typical MV Estonia passenger was a male between 34 and 44 years old, which implied that bereaved relatives could include a spouse/partner, parents, children, and siblings. Thus, different kinds of bereaved relatives may exist for each victim, as indicated in (see next page). The relationships shown are those that the deceased had with the persons who replied to the questionnaire. Thus, child or children denotes that the respondent had lost one or more children and parent or parents indicates the loss of one or two parents. The relationships stated by the relatives who responded to the questionnaires tally with those in the official police report listing 577 relatives. The largest group, both in the official police report and in our survey, was that of persons who had lost their parents. The second largest group were those who had lost a spouse/partner. The third largest group were those who had lost a child or children, followed by those who had lost siblings. The remaining groups included grandparents, in-laws, and cousins. Respondents who suffered multiple losses (for example, who had lost both a husband and children) are included in the 6% to 8% denoted as other in Figure 1.

Results

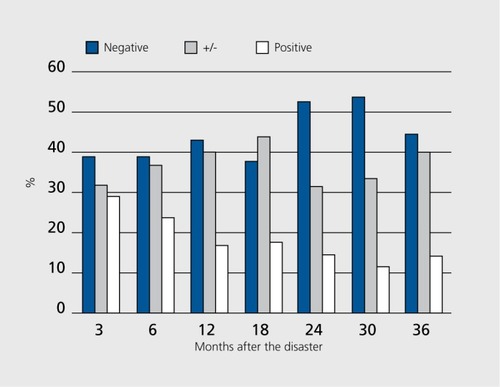

shows how the relatives rated the care they received. The ratings were classed into 3 categories (negative, positive, and in-between). In each survey, there were more people who judged the care they received as negative than those who regarded it as positive. Remarkably, the group that rated the care as positive decreased after the first year. Up until the firstyear anniversary of the sinking of the Estonia they had a more positive outlook in regard to the help they received. Thereafter, care tended to be increasingly rated as negative. In addition, many participants complained that the help they received ended too soon.

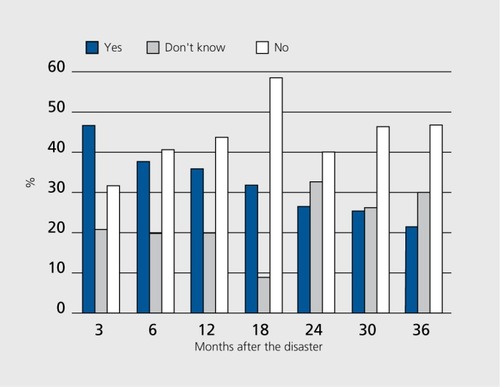

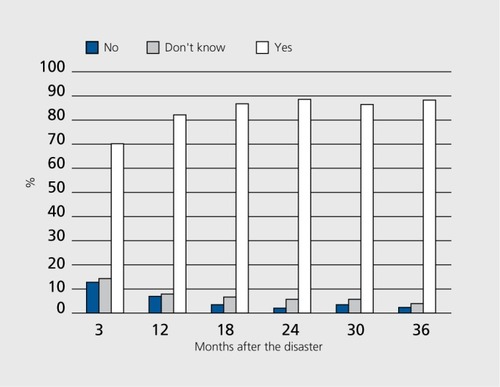

Another item in the questionnaire asked if subjects would still like to receive help (). Yes replies eventually decreased in number, but 3 years after the catastrophe, still slightly more than 20% of the relatives wanted to continue receiving help. 'Ihosc who were unsure (don't know) showed a tendency to increase and numbered 30% after the third year.

Opinions were split, among the relatives, about how to deal with the bodies of the victims and to dispose of the ship. The relatives have sometimes felt themselves to be overlooked by the decisionmakers and claim that no one listened to them. For us, at Ersta, it was very important that all opinions and all feelings in this matter should be allowed to be voiced. We did not agree that the relatives should not be asked to express their opinions and wishes. We thought it important for them to feel involved, to be seen and heard, even though everybody's wishes could not be fulfilled.

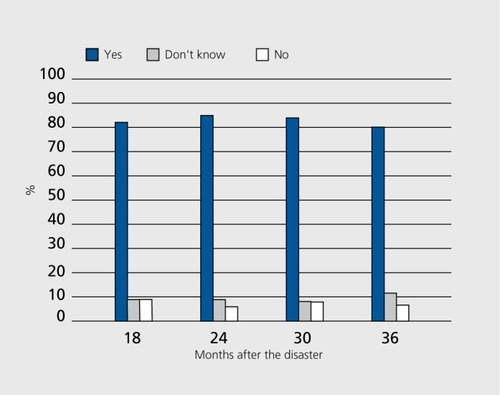

shows the responses to the question: Do you think that the authorities, before coming to a decision on December 15, 1994, should have consulted the victims' relatives regarding the salvaging of the Estonia? This question was not included in the first questionnaire, which only contained questions relating to health and disaster emergency relief. The majority of the relatives clearly wished the government had asked them for their opinion, and, as can bee seen in Figure 4, there was a noticeable increase of yes-answers with time.

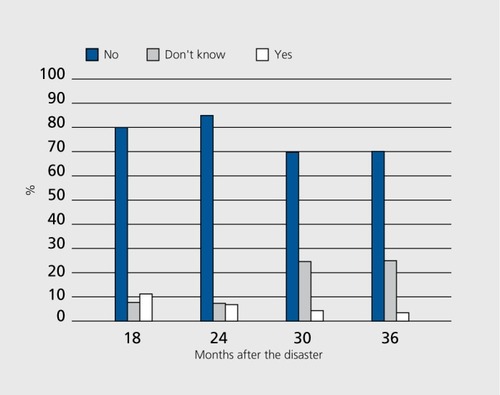

relates to the question of whether the Estonia should be covered with concrete or not. According to public authorities, this was the wish of the overwhelming majority of the relatives. However, replies concerning this point in the questionnaire 18 months after the disaster show a clear majority of no-answers. This question has evoked the most frequent written comments in the questionnaires.

The relatives who claimed to have been overlooked by the government make up ewer 80% of the total group (). This figure may have changed since the appointment by the government, 36 months after the disaster, of an Analysis Group to investigate the management of disaster emergency relief. This group gave rise to high expectations among the relatives. In November 1998, a report from that investigation group concluded that the bodies should be retrieved and buried in Swedish soil.Citation2 However, the government rejected the proposition.Citation3

Comments

This is the first paper assessing the results of our questionnaire study. Future papers will discuss the psychiatric symptoms developed by the relatives and how the tragedy affected quality of life self-ratings. Preliminary results indicate that psychiatric symptoms were correlated with the type of familial relationship, ie, that they depended on whether the bereaved relative was a parent, partner, sibling, or child.Citation8 Other publications available in English about the MV Estonia disaster include the report from the Joint Accident Investigation Commission,Citation1 a research report describing the psychiatric status among the Swedish survivors 3 months after the disaster,Citation9 as well as a chapter in a book by a Finnish psychologist describing the work of the Finnish Disaster Victims Identification Team.Citation10

Certain limitations of the present study should be noted. No thorough investigation was performed in order to draw a comprehensive list of each victim's close relatives. When a catastrophe occurs, there is always a question of who, among the victims' relatives feels close or not. We have allowed the relatives to decide for themselves on this point, ic, whether they wished to participate in the survey or not. Contact with the families was established partly through the intervention programs held at Ersta Hospital, but mainly through a letter sent to all relatives who had been listed by the Swedish government. Further analyses will be done to identify and evaluate possible selection biases.

When the first questionnaire was sent out three or four days before Christmas 1994, Ersta expected to receive many angry phone calls. Some doubt was expressed about sending the questionnaire to relatives with whom no prior contact had been made. It was difficult to imagine what it would be like to receive such a questionnaire on a tragedy of such proportions so close to Christmas from a hitherto unknown institution.

Only 1 out of the 758 recipients called to protest about the procedure, and asked to be sent no further questionnaires. However, a year later, this person relented and has since been participating in the study, as well as this person's family. Many others called to point out that the questionnaire did not include the question that was most important to them, ie, the question of salvaging the ship. It was explained to the relatives that this question should not be asked by Ersta, as we are a hospital concerned with their health and well-being, and that the government had already made the decision on December 15, 1994, not to salvage the Estonia. We contacted the Department of Communications, and tried to explain how important it was to the relatives that they be asked their opinion, in spite of the fact that the decision had already been made. However, it was clear that the government was not about to consult the relatives regarding the salvaging issue. In the end, it was decided to let the relatives themselves formulate the questions that they thought were important. So when the second questionnaire was completed, the matter of salvaging was included. In the third questionnaire, the matter of ccwering the Estonia with concrete appeared for the first time. To date, seven questionnaires have been distributed and at least two more are planned.

Conclusion

We would like to conclude this paper with a poem that a relative, a young man, sent in connection with the questionnaire. We want to show that the questionnaire study is not just important in terms of figures and charts, but that it also provided an opportunity for relatives and survivors to give vent to deep-felt emotions.

I miss my mother.

I wish she were alive again,

If only for a, day.

One hour, a few minutes,

If only for a day.

To say good-bye.

To thank her for everything she has given me.

She gave me life.

Now she has given me her last gifts,

Death and great sorrow.

Now I have received life in its entirety

This study was supported by grants from Stockholm County Council, Folksams, AMF, other companies, private individuals, and from the Swedish government. We thank Sara Gôransson and Sam Sundquist for their skillful assistance.

REFERENCES

- The Joint Accident Investigation Commission of Estonia Finland and SwedenFinal Report on the Capsizing on 28 September 1994 in the Baltic Sea of the Ro-Ro Passenger Vessel MV Estonia. Helsinki, Finland: Edita;1997228

- ÖrnP.BjörklundL.JutterströmC.NordinC.StrömholmS.En Granskning av Estoniakatastrofen och Dess Följder [An Examination of the Estonia Disaster and its Consequences]. Stockholm, Sweden: Swedish Government Publications;1998284

- ÖrnP.BjörklundL.JutterströmC.NordinC.StrömholmS.Lära av Estonia[Lessons Learned from the Estonia Disaster]. Stockholm, Sweden: Swedish Government Publications;1999228

- WinjeD.Long-term outcome of trauma in adults: the psychological consequences of a bus accidentJ Consult Clin Psychol.199664103710438916633

- WinjeD.UlvikA.Long-term outcome of trauma in children: the psychological consequences of a bus accidentJ Child Psychol Psychiatr.199839635642

- DerogatisLR.The SCL-90 1 . Scoring, administration and procedures for the SCL-90Baltimore, Md: Johns Hopkins School of Medicine;1977

- HorowitzMJ.WilnerN.AlvarezW.Impact of event scale: a measure of subjective stress.Psychosom Med.197941209218472086

- GustavssonJP.BrandängeK.After the MV Estonia disaster: a longitudinal psychiatric study on bereaved relatives. Paper presented at the 5th AEP Symposium, November 1999, Strasbourg, France

- ErikssonNG.LundinT.Early traumatic stress reactions among Swedish survivors of the m/s Estonia disaster.Br J Psychiatry.19961697137168968628

- NurmiL.The Estonia disaster: national interventions, outcomes, and personal impacts. In: Zinner ES, Williams MB, eds. When a Community Weeps: Case Studies in Group Survivorship. Philadelphia, Pa: Brunner/Mazel;19994972