Abstract

Traumatization of self-processes as a consequence of acts of war is not only determined by the content and number of traumatic experiences, but also, to a large extent by factors related to posttraumatic socioeconomic, environmental, and psychosocial interactions, À model is presented to describe posttraumatic adaptation of war-traumatized selves according to the characteristics of the individuals' social interactions and the cognitive representations of those processes. Findings in children (n=816) and adults (n=801) from postwar Bosnia are analyzed. One of the most traumatic experiences was having a missing relative, particularly a father: not knowing the fate of a close relative is an ongoing stressor that alters cognitive-emotional processes and reduces self esteem and interactional competence, whether in children or in adults. Use of a multiphasic integrative therapy for traumatized subjects (MITT) showed promising results in victims of the Bosnian war.

Los problemas de la imagen de sí mismo secundarios a traumas de guerra no están determinados sólo por las caracterícas y el número de las experiencias traumáticas, sino también - y en gran medida - por la interación de diversos factores postraumáticos de tipo socio-económicos, ambientales y psicosociales. Los autores presentan un modelo que describe la adaptación, que ocurre con posterioridad al trauma, de la imagen de sí mismo de sujetos que han sufrido traumas de guerra. En este modelo se integran las características de las inter-acciones sociales de los individuos y las representaciones cognitivas de estos procesos. Se analizan los resultados provenientes de 816 niños y 801 adultos que fueron víctimas de la guerra de Bosnia. Una de las experiencius más traumáticas fue la pérdida de algunos de los padres, particularmente la del padre. El hecho de desconocer el destino de algún familiar cercano constituye un factor de estrés permanente que altera los procesos cognitivo-emocionales, y reduce la autoestima y la capacidad de reaccionar de manera adecuada, lo que se observó tanto en niños como en adultos. La utilización de una terapia multifásica intergradora en el tratamiento de pacientes que han presentado traumas ha demostrado resultados promisorios en víctimas de la guerra de Bosnia.

Les troubles de l'image de soi secondaires à des traumatismes de guerre sont déterminés non seulement par la nature et le nombre des événements traumatisants, mais également, et pour une large part, par l'interaction d'un certain nombre de facteurs post-traumatiques socioéconomiques, environnementaux et psychosociaux. Les auteurs présentent un modèle permettant de décrire les processus d'adaptation post-traumatique chez les sujets ayant développé des troubles de l'image de soi lors de traumatismes de guerre en fonction des interactions de l'individu avec son environnement social et de sa représentation cognitive de ces événements. Les résultats ont été recueillis et analysés chez 816 enfants et 801 adultes victimes de la guerre en Bosnie. L'un des événements les plus traumatisants est représenté par la perte d'un parent, en particulier lorsqu'il s'agit du père. Le fait d'être dans l'ignorance du sort subi par un parent proche constitue un facteur de stress permanent à l'origine de troubles cognitifs et émotionnels avec, en particulier, une diminution de la confiance en soi et de la capacité de réagir de façon adéquate, aussi bien chez l'adulte que chez l'enfant. Une thérapie multiphasique d'intégration a été proposée pour les traitement des victimes de la guerre de Bosnie et les résultas obtenus semblent prometteurs.

Theoretical aspects

The traumatized self

Although true of most conflicts, that which took place in Bosnia between 1993 and 1995 was characterized by the fact that a great number of acts of extreme cruelty were waged specifically against civilians. This implies that war-related traumatization is not solely attribut able to physical injury, life-threatening events, or the social consequences of displacement or deportation, but that loss of interpersonal trust plays a paramount role as well. Thus, among the many areas that must be addressed when designing therapeutic methods to deal with traumatized individuals, particular emphasis should be placed on self-processes as a representation of social interactions and the violation/distortion of these self-processes by the experience of a. traumatic incident.

This concept is in strong support of a more dialectical approach to the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Equating self-processes with representations of social interactions implies that distorted interactions, which have been shown to develop in the wake of most traumatic incidents, exert a dramatic influence on these self-processes. If such is the case, then therapy must deal in priority with interactional experiences.

Our treatment approach was originally developed for patients having experienced a single traumatic event occurring in a civilian setting, such as an accident or exposure to violence or sexual assault. It was later applied to war traumatization in Bosnia, during the war and in the postwar period. Joint projects were carried out with workers at the University of Sarajevo to study the diagnosis of PTSD, empirical treatment, and therapeutic processes (for further details, see references 1-7).

The social interaction model

Throughout our lives, we develop models based on our experience of the world in which we live and of the other human beings with whom we come into contact. Our expectations about future experiences and behaviors are largely influenced by these models, which are constantly being revised, as new experiences add to previous ones to gradually evolve and stabilize into a set of models of reality out of which we somehow “create” our own representations of our selves and of the world. The complexity of these models depends on many factors, including the sophistication of a given individual's cognitiveprocessing system, as reflected in its selection, memory, and retrieval functions, and probably several other factors as well. Similar to our representations of the “physical” world, the configuration of our self-processes is determined by the experience of interactions between ourselves (the acting person) and our world.

Phases of posttraumatic adaptation

Under normal conditions, new experiences do not differ drastically from our expectations, so that we are able to adapt our models of the world, our self, and the resulting interactions in a more or less smooth and gradual way.

In contrast, traumatic experiences are, by definition, far removed from what an individual expects in so-called normal-life situations, and as a result, cognitive and emotional functions must adapt in order to restore congruency between the individual's model of the world, self, and the traumatic experiences that are being integrated. Cognitive and emotional attempts to integrate traumatic experiences appear to run through different phases and levels, in which the coping processes vary in complexity and goals. Strategies that are helpful in the aftermath of a traumatic incident might be counterproductive or even harmful at a later stage, and vice versa. During the acute phase of trauma, the coping process aims to achieve a general reduction in stress through the use of “inner” and “outer” (cognitive and behavioral) strategies such as escape or avoidance. During the later phases of posttraumatic adaptation, particularly in the event of failure to deal successfully with the traumatic experience in its entirety, coping strategics focus on denial of either the experience as a whole or some of its aspects, as subjects try to hold on to the remnants of competence and coherence of the pretraumatic self.Citation8 In contrast, individuals who feel relatively secure and strong, who are again able to engage in well-integrated relationships and have reccwered their competence in dealing with everyday issues, attempt to confront the memories of the traumatic events emotionally and cog nitively, even though the stresses experienced at the time risk being reawakened in the process. This takes place through a step by step approach of the sealed memories of the experiences that were unbearable in their full extent when the traumatic incident took place.

Unanswered questions

The above considerations give rise to a certain number of questions. One problem is that the models of posttraumatic adaptation on which therapeutic concepts are based are purely theoretical,Citation8 without there being, to date, any confirmation by empirical evidence: what, therefore, is the validity of current therapeutic practice? Another important question relates to the extent of posttraumatic adaptation: traumatized subjects appear to be able to integrate their experiences in such a way that their old models of the world are not completely shattered, but are replaced by new ones influenced by the implications of the traumatic experience, ie, they do not attempt to rigidly restore the old models by ignoring or denying the impact of the traumatic incident. How is this possible, and which processes are involved? It is with these questions in mind that we carried out our studies on Bosnia war victims' adaptive skills in overcoming trauma, in the hope of finding some answers.

Studies on war traumatization in Bosnia

Stress in children whose father is missing, separated from them, or dead

Children from war areas who are displaced or obliged to seek asylum in foreign countries have to cope with multiple traumatic experiences, one of the most serious being the loss of a father, who has either been killed or is missing.

We carried out a study in the canton of Sarajevo on 816 children and early adolescents (age 10-15 years). The main goal of the study was to look at the psychological effects of traumatic experiences caused by the loss of a father as a consequence of the war.Citation9

This study evaluated the number of traumatic experiences during the war and in the postwar period, and measured depressive symptoms using Birleson's Depression Self-Rating Scale for children (DSRS).Citation10

Four groups of children were defined as follows:

Missing fathers: Children who lost contact with their father during the war and had still not received any information about his fate at the time of the study (n=201; 106 boys, 95 girls) .

Separation: Children who were separated from their father during the war, but could be reunited with him after the war (n=204; 104 boys, 100 girls).

Kitted fathers: Children whose fathers were killed during the war; the children had full knowledge of the fact and circumstances (n=208; 105 boys, 103 girls).

Controls: Children not having lost or been separated from their father; ail other factors were the same as in the other groups (n=203; 99 boys, 104 girls).

Table I shows the average number of traumatic experiences other than the loss of a father. The fact the number of such experiences was significantly higher in the group with fathers missing is worthy of note.

table I War-related traumatic experience (WRTE) and postwar-related stress (PWRS) in children.

A potential confounding factor with respect to depressive symptoms was the possibility that a child's lack of information about a close relative could be a consequence of the chaotic circumstances brought about by “ethnic cleansing,” the latter being in itself associated with higher trauma scores. An analysis of covariance was therefore performed in order to correct for the confounding effect of this ccwariate on the variable “depression.” The main depression scores, adjusted for covariates, are shown in Table II. The differences among the groups were highly significant, and, again, the highest depression scores were found in the children with a missing father, with almost as high scores in children whose father had been killed. These results highlight the cognitive processes that are triggered in children who lose a parent through acts of violence or who are left with no information concerning the fate of their father, and that uncertainty with respect to family members was the strongest factor in childhood depression.

Table II Depression and losses in children. WRTE, war-related traumatic experience; PWRS, postwar-related stress.

Traumatic and stressful events experienced by adults with different flight paths

Profile of traumatic events and exposure to stress

In a second study, we looked at the types of stressful and traumatic events and situations experienced during and after the war by adults with different flight paths (returnees, displaced people, and “stayers”).Citation11

The study was carried out in a total sample of 501 subjects consisting of 5 subgroups of returnees, displaced people, or stayers, from Sarajevo (capital of BosniaHerzegovina) and Banya Luka and Prijedor (northwest of Sarajevo, now in the Serb Republic). We used a checklist taken from the first section of the Modified Posttraumatic Stress Symptom scale (PSS) made up of 130 different traumatic and stressful events. For convenience of evaluation, these 130 items were divided into 10 different event clusters (groups), such as total events in war zone, expulsion and flight, time spent in concentration camps or temporary shelters, etc, and statistical evaluation was carried out separately for each event group (Table III).

Table III War events and displacements.

One of the most important findings was that the Sarajevo returnees had about as much exposure to the war and war events as the two displaced groups from the Serb Republic. The returnees and displaced people had spent a great deal of time in temporary shelters and collective centers (Table IV). Not surprisingly, all subjects had experienced appalling losses. Subjects housed in collective centers are those experiencing a particularly high level of current stress (see next section). Each group had a distinctive profile of traumatic events and other stressors. 'Ihc Banja Luka stayers seemed to have been somewhat better off, while the two Sarajevo groups experienced the highest number of traumatic events and other stressors. It should be noted that exsoldiers were not excluded from the study population.

Table IV Vicarious traumatization and losses.

Correlation with current symptoms

Most of the events and event groups described are correlated with current psychological distress: the greater the subjects' exposure to such events, the worse their current symptoms of distress. We used the SCL-90-R Symptom Checklist to measure these symptoms.Citation12 This checklist records psychologically relevant symptoms, such as headaches, anxiety, or hearing voices that are not there.Citation12

It should be stressed that the mere presence of a correlation between the occurrence of a given group of events and the presence of current symptoms does not necessarily imply that a causal relationship exists. For instance, it is possible that some groups of events are highly correlated with symptoms just because they occurred together with other events which themselves have a genuine causal relationship with symptoms. À regression analysis was therefore carried out to try to determine the specific effect of each of these event groups on symptoms, independently of the influence of the other groups. The event groups characterized by the strongest specific influence on psychological status in this analysis are italicized in Tables III and IV. Regression analysis showed that the most psychologically debilitating event groups were traumatic events sustained during the war and difficult present-day personal and social circumstances. However, this is only a preliminary analysis; much more work needs to be done, for instance, to isolate as many of the factors that predict particular psychological problems as possible.

Psychological profile ofnon-PTSD sufferers

Psychological adjustment is important not just because it is an indication of the pain, optimism, etc, experienced by the citizens of Bosnia-Herzegovina, but also because it has a major influence on the reconstruction of the country. To take but one example, depression is a major obstacle because even the most talented or resourceful people achieve very little for themselves or others if they are depressed or hopeless.

We therefore sought to identify the specific needs in terms of psychosocial intervention for each of the study's subgroups.

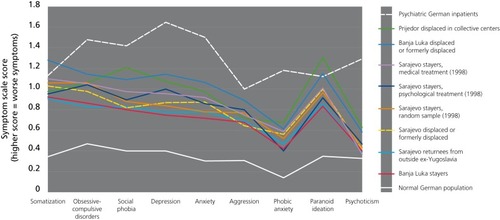

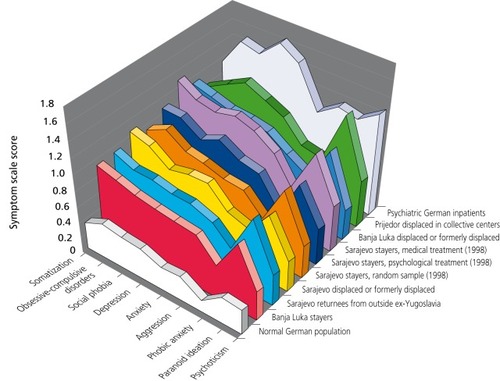

German subjects with no noteworthy psychological history and German psychiatric inpatients were used as reference groups, and three additional semirandom comparison groups of stayers identified by our Research Institute in Sarajevo in 1998 were included: a medical treatment group, a psychological treatment group, and a random group of Sarajevo residents, with n=100 for each group. and 2 (next page) show the scores for items as defined by the SCL-90-R checklist. It is not, at present, completely clear to which extent the differences in symptom scores found in comparison with the reference groups is attributable solely to war and postwar stress, or could reflect, at least in part, cultural differences between Bosnian and German subjects.

Symptom scores in all groups of Bosnian subjects were significantly higher than in the reference samples, but not, however, as high as would be expected in psychiatric inpatient populations. .Predictably, the Banja Luka stayers had the fewest symptoms. The subjects with the highest symptom scores were the Prijedor and Banja Luka groups of persons displaced in camps. In Sarajevo, the returnees had slightly fewer symptoms than the displaced groups, who were about as well adjusted as the stayers were in 1998. shows the same findings in a different way, which makes it easier to compare the study group profiles with respect to the reference groups. 'Ihe profiles of the postwar Bosnia-Herzegovina groups are very distinctive, showing a peak for the item “paranoid ideation,” (encompassing suspiciousness and the feeling of being isolated), and a lesser elevation of passive symptoms such as anxiety and depression , in comparison with aggression, paranoid ideation, and somatization.

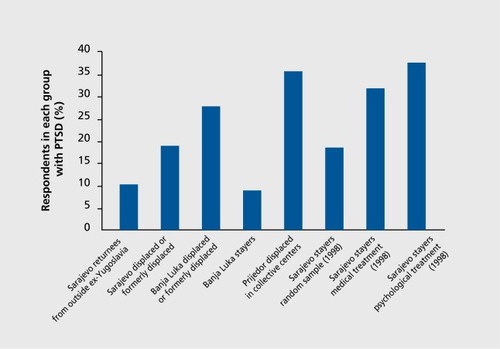

Psychological profile of PTSD sufferers

Alongside the high incidence of general psychological symptoms in our population of subjects exposed to the war in Bosnia, there was also a high incidence of PTSD. This is a serious disorder that has extremely unpleasant consequences for those affected and significantly alters their daily functioning at work and in the family. shows that these subjects had a distinctive psychological profile, characterized by hyperarousal (sleeplessness, restlessness), reexperiencing of the events (nightmares, flashbacks), and avoidance (trying not to think or talk about the events, emotional numbing). It should be noted that, as in Figures 1 and 2, three semirandom samples of Sarajevo stayers from 1998 were included in Figure 3 for the purpose of comparison.

Between 10% and 35% of subjects in the nontreatment group were diagnosed as having PTSD. The differences observed in terms of incidence of PTSD among the study groups were much greater than those relating to general psychological symptoms (see preceding section). Unsurprisingly, the subjects exposed to the highest level of war stresses showed the highest incidence of PTSD. However, the displaced subjects placed in collective centers had the highest incidence of PTSD among the 1999 groups, which could indicate that particularly difficult social circumstances can significantly contribute to the maintenance of PTSD. The incidence of PTSD was higher in older people and women. This broadly agrees with results in the international literature on PTSD, although further research is needed to investigate differential exposure to traumatic events. 'Ihe results for general psychological symptoms as measured by the SCL-90-R checklist are very similar.

Therapeutic implications

Multiphasic integrative therapy for traumatized people (MITT)

After presenting the theoretical aspects of self-processes and posttraumatic adaptation and discussing the findings from our two studies carried out on Bosnian war victims, we now look at the contribution of what we have termed a social interaction therapeutic approach to rebuilding self-processes shattered by traumatic experiences. This approach is based on enabling patients to achieve a successful integration of pretraumatic, traumatic, and posttraumatic experiences in a mature way. The social interaction model outlined is, in fact, more a heuristic guideline than a therapeutic technique as such. Its role is to help select appropriate therapeutic methods and techniques during the different phases of posttraumatic adaptation, and adjust them according to the speed of the individual's recovery and the level at which he or she operates. These include techniques to reduce characteristic posttraumatic symptoms like intrusion, hyperarousal, avoidance, depression, feelings of insecurity, cognitive deficits, flashbacks, sleep disturbances, bad dreams, dissociation processes, social isolation, achievement difficulties, concentration problems, etc. However, as the theoretical model predicts, and our empirical data show, social, economic, and educational support is important too, and has a synergistic effect on the outcome of psychological intervention.

In general, patients, particularly in the posttraumatic phase, show great motivation for therapy provided the therapist is ready to work with them on their symptoms. However, the patient's motivation often undergoes fluctuations due to the interference of intrusions, avoidance patterns, or plain socioeconomic problems, which affect the dialectical (social interactional) aspect and the selfprocesses. 'Ihe social interaction model of the traumatized self allows symptom-oriented or psychosocial therapy to be more effectively focused, thus helping patients whose self-processes are shattered by traumatic experiences to restore self-assertiveness and self-stability.

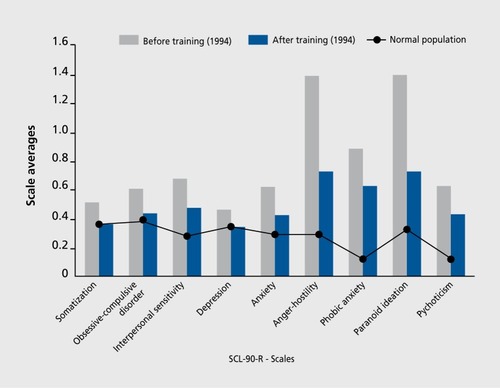

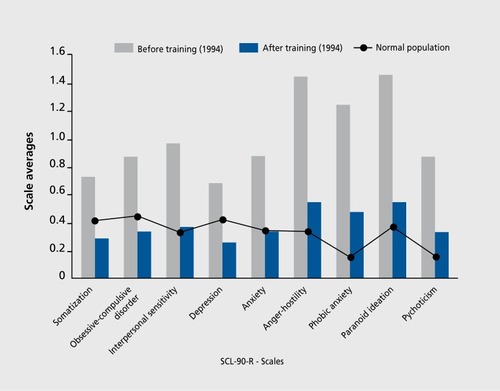

This therapeutic approach was used in a series of training programs throughout Bosnia. Actual training started during the war in 1993 and was continued after the war, with the support of UNICEF (the United Nations Children's Fund) and Volkswagen-Stiftung. During the war, the training program was offered to local professionals and paraprofessionals, who worked in camps, for nongovernmental organizations, and in hospitals. The training was offered in various towns in Bosnia to groups of up to 30 participants. 'Ihe principal goals of this training were to provide role models for therapy and technical skills, but we also helped to combat burnout and treat trauma disorders of participants whose war-shattered self-processes badly needed support. During this period, research was not in the forefront of our work. As a feedback for us, as trainers, and for the participants, we used the SCL-90-RCitation12 checklist to assess the stresses the participants were exposed to and their reactions to these stresses. Figures 4 and 5 show some of the results using group averages (before and after training sessions). It can be seen that, at the beginning of the two different workshops (in 1994 and 1995), most of the participants were in a severe state, with a large number of symptoms and scores on the scale clearly above the clinical norms, and that these scores had already dramatically changed during the first week of training (). The second training session took place in 1995 in the same group. shows evidence of the stresses of another year of war, with scores even higher than at the beginning of the 1994 workshop. Again, after training, the participants recovered their liveliness and optimism, and the extreme values of their scores were dramatically reduced again.

One could question the usefulness of this type of training if its results were short-lived. Considering the decay of clinical scores during an ongoing war situation, critics might be right. However, our data show that the effect on our Bosnian colleagues' depression, despair, and fear was very positive, at least in the short- and mid-term. They certainly recovered enough of their former capabilities, which they in turn were able to apply to their patients and family, to carry them - at least for a fewweeks or months - through shelling, hunger, life -threatening events, and expulsion experiences, and - the experience reported as the worst - the daily discovery that friends have given up and left the country as refugees to take themselves and their families to safer places. However, our results also show that the training sessions should have been offered much more frequently. Traumatic stress, such as that experienced in the wake of the recent war in Bosnia, seems to exert an imprinting effect, with devastating consequences on self-processes. One positive aspect, however, is that persons who share such experiences tend to develop long-lasting bonds and solid friendships. This was verified in both the trainers and the trainees in Bosnia.

Selected abbreviations and acronyms

| DSRS | = | Depression Self-Rating Scale |

| WRTE | = | war-related traumatic experience |

| PWRS | = | postwar-related stress |

| MITT | = | multiphasic integrative therapy for traumatized people |

| PSS | = | Posttraumatic Stress Symptom scale |

| PTSD | = | posttraumatic stress disorder |

| SCL-90-R | = | Symptom Checklist %-R |

We are grateful to Volkswagen-Stiftung, Hannover, which supported the studies described in this paper.

REFERENCES

- ButolloW.Psychotherapy integration for war traumatization - a training project in central Bosnia.Eur Psychologist19961140146

- ButolloW.“Denn traumatisiert sind wir hier aile”: Psychologische Notizen aus Sarajewo.Report Psychologie.199710766772

- ButolloW.Traumapsychologie und Traumapsychotherapie - Eine Herausforderung für Psychotherapeutische Praxis und Forschung.Psychother Psychiatr Psychother Med Klin Psychol.199712334

- ButolloW.Traumatherapie - Die Bewältigung schwerer posttraumatischer Störungen. Munich, Germany: CIP - Mediendienst; 1997

- ButolloW.KrüsmannM.HaglM.Leben nach dem Trauma: Über den ther apeutischen.Urngang mit dem Entsetzen. Munich, Germany: Pfeiffer Verlag;1998

- ButolloW.HaglM.KrüsmannM.Kreativität und Destruktion posttraumatischer Bewältigung. Forschungsergebnisse und Thesen zum Leben nach dem Trauma. Munich, Germany: Pfeiffer Verlag;1999

- ButolloW.GavranidouM.Intervention bei traumatischen Ereignissen. In: Oerter R, Hagen CV, Röper G, Noam G, eds.Klinísche Entwicklungspsychologie. Weinheim, Germany: Psychologische Verlagsunion;1999chap19

- HorowitzMD.Stress-response syndromes. A review of posttraumatic stress and adjustment disorders. In: Wilson JP, Raphael B, eds.International Handbook of Traumatíc Stress. New York, NY: Plenum Press;19934960

- ButolloW.ZvicdizS.War-related losses and depression in children. Paper presented at the German Congress of Psychology (DGfPS), Jena, Germany; 2000

- BirlesonP.HudsonI.BuchananDG.WolffS.Clinical evaluation of a self-rating scale for depressive disorder in childhood (depression self-rating scale).J Child Psychol Psychiatry.19872843603558538

- PowellS.RosnerR.ButolloW.Flight Paths. Report to the Office of the Federal Government Commissioner for the Return of Refugees, Reintegration and Related Reconstruction in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Hans Koschnik; 2000

- DerogatisLR.Symptom-Check-Liste (SCL-90-R). In: Collegium Internationale Psychiatriae Scalarum.internationale Skalen für Psychiatrie. Weinheim, Germany: Beltz;1986