Abstract

In 1936, two clinical rewiews, one by de Morsier, the other by L'Hermitte and de Ajuriaguerra, formulated an approach to visual hallucinations that continues to this day. Breaking with previous traditions, the papers championed visual hallucinations as worthy of study in their own right, de-emphasizing the clinical significance of their visual contents and distancing them from visual illusions. De Morsier described a set of visual hallucinatory syndromes based on the wider neurological and psychiatric context, many of which remain relevant today; however, one - the Charles Bonnet Syndrome - sparked 70 years of controversy over the role of the eye. Here, the history of visual hallucinatory syndromes and the eye dispute is reviewed, together with advances in perceptual neuroscience that question core assumptions of our current approach. From a neurobiological perspective, three syndromes emerge that relate to specific dysfunctions of afferent cholinergic and serotonergic visual circuitry and promise future therapeutic advances.

En 1336, dos revisiones clínicas (una de De Morsier y la otra de L'Hermitte y Ajuriaguerra) formularon una aproximación a las alucinaciones visuales que se mantiene hasta el día de hoy. Alejándose de las tradiciones previas, este artículo aboga porque las alucinaciones visuales sean dignas de estudio por derecho propio, sin hacer énfasis en el significado clínico de sus contenidos visuales y tomando distancia de las ilusiones visuales. De Morsier describió un conjunto de síndromes alucinatorios visuales basados en un contexte neurológico y psiquiátrico más extenso, muchos de los cuales son hasta hoy día relevantes; sin embargo, uno de ellos - el Síndrome de Charles Bonnet - ha motivado 70 años de controversia acerca del rol del ojo. En este artículo se revisa la historia del conflicto entre los síndromes alucinatorios visuales y el ojo, junto con los avances en las neurociencias de la percepción que cuestionan las principales hipótesis de la aproximación actual. Desde una perspectiva neurobiológica surgen tres síndromes que se relacionan disfunciones específicas de los circuitos visuales aferentes, colinérgicos y serotoninérgicos, y prometen futuros avances terapéuticos.

Deux études cliniques, décrites en 1936 par de Morsier et de L'Hermitte et Ajuriaguerra, ont présenté une approche des hallucinations visuelles qui perdure aujourd'hui. Rompant avec les traditions antérieures, ils défendent dans leurs articles les hallucinations visuelles comme dignes de sujet d'études, minimisant la signification clinique de leur contenu visuel et les différenciant des illusions visuelles, De Morsier a décrit un ensemble de syndromes hallucinatoires visuels rentrant dans un large cadre neurologique et psychiatrique dont la plupart demeurent pertinents actuellement; l'un d'entre eux, le syndrome de Charles Bonnet, a fait néanmoins l'objet de controverses durant 70 ans au sujet du rôle de l'œil. L'anamnèse des syndromes hallucinatoires visuels et la discussion sur l'œil sont ici analysées à la lumière des avancées des neurosciences de la perception qui remettent en question les hypothèses centrales de noire approche actuelle. D'un point de vue neurobiologique, trois syndromes se distinguent en se rattachant à un dysfonctionnement spécifique des circuits visuels sérotoninergiques, cholinergiques et afférents; ils sont prometteurs d'avancées thérapeutiques dans le futur.

Visual hallucinations came of age In 1936 with the publication of two clinical reviews. The first, a modest 2-page essay, appeared in the relative backwater of a parochial Swiss medical journal, authored by George de Morsier, then a recently appointed lecturer in neurology.Citation1 The second appeared in the Annales Médico-Psychologiques, the high-profile voice of French-speaking psychiatry, coauthored by the neurologist Jean L'Hermitte, an established expert in the field following his earlier description of peduncular hallucinations, and the psychiatrist Julian de Ajuriaguerra, then aged 25 and at the beginning of his career.Citation2 Both reviews shared three important breaks with tradition. First, visual hallucinations were deemed worthy of study in their own right, distinct from hallucinations in other modalities and from other forms of psychopathology Second, they were to be considered a unitary symptom. An earlier generation of psychiatrists had hoped that different types of visual hallucination might carry different diagnostic implications; however, from here on, the important clinical detail became whether a given patient experienced visual hallucinations of any kind, not whether they had hallucinated a simple lattice pattern as opposed to a procession of animals or an elaborately costumed figure, for example. The third break with tradition was to distance visual hallucinations from visual illusions, giving them a higher clinical status. Yet, although sharing much in common, the two papers differed in their conception of the brain and its disorders. L'Hermitte and de Ajuriaguerra looked forward to emerging holistic models of psychopathology, viewing visual hallucinations as part of a general hallucinatory state. Although classifying the clinical conditions associated with visual hallucinations by the location of the underlying visual system lesion, their scheme was not intended to imply a range of distinct syndromes. In contrast, de Morsier's approach looked back to the classical era of associationism (see ref 3), viewing visual hallucinations as a localizing neurological symptom that, when considered in its wider clinical context, formed distinct syndromic entities. This syndromic approach captured the clinical imagination and remains an important influence today, in part the result of later disagreement between de Morsier and de Ajuriaguerra over the role of the eye in visual hallucinations. In order to understand the origin of de Morsier's syndromes, we must first turn to the Parisian Central Police station.

de Clérambault and the origins of hallucinatory syndromes

The Special Infirmary of the Parisian Central Police station (the Dépôt) held a particular mix of clinical cases. Differing from other psychiatric centers in Paris, it was responsible for the assessment of police detainees with behavioral disturbances and, in consequence, held a heavy caseload of delirium, dementia, and chronic hallucinatory psychosis. Gaétan de Clérambault (1872-1934) was appointed director in 1921, but had been associated with the Special Infirmary since 1905,Citation4 developing a general theory of psychopathology based on the case mix - the theory of mental automatisms. Influenced by Wernicke's associationist school (see ref 3), de Clérambault viewed psychosis as the sum of core neurological symptoms, each related to dysfunction in a specific brain system (see ref 5 for further details). Aberrant neural activity was propagated from one brain region to another along anatomical pathways, the linked neurological symptoms forming stereotyped neuropsychiatrie syndromes. Georges de Morsier studied under de Clérambault and carried an interest in psychiatric phenomena, particularly hallucinations, to Geneva. In 1930 he published a critique of Bleuler's and Freud's psychological theories of hallucinations, in which he argued that future advances could only be made through the neurophysiological study of hallucinations, although the techniques required were not yet available.Citation6 His interim solution was to use lesion evidence as an indirect guide to dysfunctional neurophysiology and, in the aftermath of de Clérambault's suicide of 1934, he published two homages to his former mentor using this method. The later work of 1938, Les Hallucinations: étude Oto-neuro-ophtalmologique,Citation7 covered hallucinations in all sensory modalities and opened with a dedication to de Clérambault's memory. The earlier work of 1936 focused on visual hallucinations and honored de Clérambault by paraphrasing his mental automatism terminology in the title, Visual Automatisms: Retrochiasmatic Visual Hallucinations).Citation1 The topic seemed appropriate, as visual hallucinations had been relatively unexplored in de Clérambault's later work. However, there was another reason for de Morsier to focus on visual hallucinations alone - he had just developed a novel anatomical theory.

The early 20th century visual system

Although the division of the visual system into visuosensory and visuopsychic components was first formulated in the 19th century, it was the Australian neurologist, psychiatrist, and pathologist, Alfred Walter Campbell (1868-1937) who in 1905 provided anatomical evidence in support of the functional dichotomy.Citation8 Campbell had described two cyto- and myeloarchitectonically distinct regions in the occipital lobe of the human brain. The striate cortex received connections from the lateral geniculate nucleus (the geniculo-striate pathway) and sent fibers to the surrounding cortex, which in turn sent projections to the pulvinar, temporal, and frontal lobes. Campbell argued that the striate cortex received crude sensory impressions, implying a visuosensory function for the region. In contrast, the surrounding cortex received more complex inputs, implying a visuopsychic function, further elaborated through temporal and frontal projections. A link between the geniculo-striate pathway and visual hallucinations had first been recognized in 1886 by Seguin,Citation9 who described the occurrence of visual hallucinations within a visual field defect. De Morsier had presented a case at an international congress in London in 1935 with hemifield visual hallucinations without a visual field defect, and had concluded that visual hallucinations could also be associated with lesions of the paravisual sphere, a term he attributed to Hoff and Pötzl describing connections between the pulvinar and visual cortices (see ref 10 for a recent anatomical description).

Visual hallucinatory syndromes past: de Morsier's syndromes

De Morsier's 1936 and 1938 papers viewed visual hallucinations as a stereotyped automatism of the broadly defined visual system including the paravisual sphere and temporal lobes. Damage to the system at different locations would associate visual hallucinations with varying combinations of motor, vestibular, and auditory symptoms and, with a lifelong interest in the history of the field,Citation11 de Morsier attached names to the resulting syndromic entities, outlined in Table I. The main part of his 1936 work was a syndrome he named after Hermann Zingerle (1870-1935), an Austrian neurologist from Graz with an interest in motor automatisms. This consisted of visual hallucinations in the context of oculogyric crisis, persistent movement disorder, and central vestibular symptoms attributed to lesions of the parietal lobe. The modern equivalent would perhaps be the positive visual phenomena (typically intensification of visual patterns and letters) associated with neuroleptic-induced oculogyric crises.Citation12,Citation13 De Morsier also honoured de Clérambault with a syndrome - not erotomania but the chronic hallucinatory psychosis which had helped derive the theory of mental automatisms. L'Hermitte was honoured with the peduncular syndrome, although de Morsier argued that the important lesion was in the pulvinar, not the cerebral peduncles. Other visual hallucinatory syndromes he described were not named. One concerned the visual hallucinations found in delirium tremens that had been studied by his friend and colleague in Geneva, Ferdinand Morel. These hallucinations had the unusual property of being precipitated when one eye was covered, typically the eye with better acuity, and were located in the central 10 to 15 degrees of the visual field. Neurodegenerative, vascular, neoplastic, toxic, traumatic, inflammatory, and epileptic etiologies were also included. Although incomplete, much of de Morsier's classification remains relevant today, some of his notable omissions conditions that had yet to be described. Current classifications would Include dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and narcolepsy (visual hallucinations forming part of the diagnostic criteria In these disorders), Parkinson's disease (PD), migraine, bereavement, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA-ecstasy), visual sensory deprivation, and stroboscopic stimulation (Table II; see refs 14, 15 for recent reviews). However, de Morsier's classification Is perhaps most remembered for one syndrome, mentioned In passing, that sparked a 70-year controversy.

Table I. de Morsier's classification of visual hallucinatory syndromes.

Table II. Visual hallucinatory syndromes not included by de Morsier. LSD, lysergic acid diethylamide; MDMA, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder

The Charles Bonnet syndrome

De Morsier included a brief mention of a syndrome Inferred from reports In the literature. Charles Bonnet's description of the visual hallucinations experienced by his 89-year-old grandfather Charles Lullin (see ref 14 for detailed account) had been largely overlooked in the early 20th century visual hallucination literature. However, the account was well known to de Morsier through accidents of birth and geography. His mother was related to Theodore Flournoy and Edouard Calparède, cousins themselves and founding editors of the Archives of Psychology, Flournoy had inaugurated the first issue with a commentary and transcript of Lullin's original observations that survived in the collections of a surgeon,Citation16 and in 1909 an autobiographical report of the 92-year-old philosopher Ernest Naville's visual hallucinations were published in the same journal.Citation17 Bonnet, Lullin, Naville, Flournoy, and the Archives of Psychology were all linked to Geneva - then, and for the remainder of his life, de Morsier's home. Basing his syndrome on these published accounts, he argued that visual hallucinations could occur in the absence of cognitive Impairment In the elderly, a syndrome he referred to as the Charles Bonnet syndrome (CBS). For de Morsier, CBS Implied a localized neurodegeneration and contrasted the association of visual hallucinations and dementia in Alzheimer's disease (AD) and Pick's disease. Although he did not specify the site of the theoretical neurodegenerative lesion, he later revealed his suspicion that it involved the paravisual sphere,Citation18 the pulvino-cortical connections he had linked to visual hallucinations in 1935.

The ocular theory

Although de Morsier was unable to confirm his neurodegenerative hypothesis, he was certain of one thing: CBS had nothing to do with eye disease. For him the fact that Charles Lullin had impaired vision was no more than a coincidence of the fact that eye problems were common in the elderly. His position was to influence developments in the field for the next 70 years, and had its roots in a debate that had taken place the previous decade in the ophthalmological literature. A French ophthalmologist, Victor Morax (1866-1935) had provided what seemed to be compelling clinical evidence of a link between eye disease and visual hallucinations in 1922.Citation19 He had presented a case with an exact temporal correspondence of visual loss and the onset of figure and landscape hallucinations. Morax's derived a theory of their cause based on positive scotoma, dark areas of the visual field related to retinal lesions. He argued that positive scotoma occurred when aberrant retinal impulses were conducted to the brain, and were absent when such conduction could not take place, for example through retinal fiber loss. Visual hallucinations in eye disease were simply a more elaborate form of positive scotoma in which the aberrant retinal signals were conducted beyond the visual cortex to its associative centers. Other ophthalmologists joined Morax with further reports of temporal associations (eg, TrucCitation20) and two psychiatrists, Brunerie and Cloche, presented a case in which visual hallucinations resolved after a cataract operation.Citation21 Arthur Ormond, an ophthalmologist at Guy's hospital in London, published his own cases in 1925Citation22 and, influenced by Galton's work on visual imagery, concluded that visual hallucinations were related to a hypersensitivity of specialized visual cortical areas, triggered in some cases by eye disease.

Yet not all ophthalmologists agreed with the ocular theory. In France, Terson summarized in a single phrase the seemingly incontrovertible evidence against the eye as a primary cause of visual hallucinations: “[...]consider the vast number of cases of eye disease without hallucinations and hallucinations without eye disease.”Citation23

In his view, additional toxic or inflammatory brain factors were invariable in such patients. Eye disease itself could not be an important factor as visual hallucinations could occur without it, in its presence or after it had resolved. L'Hermitte and de Ajuriaguerra's 1936 paper added further weight to Terson's counterargument with post-mortem evidence of a patient with visual hallucinations in which thalamic lesions were found in addition to eye disease.Citation2 They also argued that aberrant retinal signals could at best only engender simple hallucinatory forms and should cease with eye closure, a maneuver that only seemed to influence hallucinations in a few patients. They did not dismiss the possible role of the eye but believed it, at best, a secondary factor. De Morsier incorporated this view into his 1936 and 1938 papers, citing L'Hermitte as having disproved the ocular theory For de Morsier, eye disease was not the cause of CBS, or indeed visual hallucinations under any circumstances, and was specifically excluded from his classification. However, it is clear that in 1938 at least, de Morsier's opposition to the eye was specific to the aberrant retinal impulse theory In response to the commentary on his 1938 paper, he agreed with Velter that a reduction in acuity through eye disease might provoke visual hallucinations,Citation24 a view that differs little from modern deafferentation theory (see below). Yet circumstances were later to push de Morsier even further from this concession to the eye.

Charles Bonnet Syndrome defined by eye disease

De Morsier's Charles Bonnet eponym was immediately popular, other clinicians using the term by the time his response to the commentary on his 1938 paper was published.Citation24 Yet, although CBS survived the second world war, his insistence that it was unrelated to eye disease did not. In 1956, Hécaen and Garcia Badaracco acknowledged de Morsier for introducing CBS but did not agree with his antiophthalmological stance, shifting the definition to the very ground de Morsier had tried to dismiss - visual hallucinations in eye disease.Citation25 For Hécaen and Garcia Badaracco, as for L'Hermitte and de Ajuriaguerra 20 years before, it was the combination of eye and cerebral pathology that resulted in visual hallucinations, a dual pathology encapsulated in Bonnet's description of the elderly, visually impaired Lullin. The redefinition constituted a blow to de Morsier's intended syndrome, but it was the return of de Ajuriaguerra that finally sealed its fate.

De Ajuriaguerra was appointed Director of Psychiatry at the University of Geneva in 1959, overlapping the last 5 years of de Morsier's tenure as Director of Neurology In the year of de Morsier's retirement, he organized an international conference on the psychopathology of deafferentation, referring to CBS in his own presentation with Garrone as “visual hallucinations in eye disease.” de Morsier was mentioned in passing amongst authors who had written on the topic, but de Ajuriaguerra cited his own work with L'Hermitte and that of Hécaen and Garcia Badaracco as the two major previous reviews.Citation26 The following year, with coauthors Burgermeister and Tissot, he presented afresh the clinical details of the six cases he had first described with L'Hermitte, relabeling them as CBS.Citation27 His position had shifted slightly in the intervening 29 years, the eye and brain now carrying equal weight as causal factors, as opposed to the eye as secondary to the brain. Visual hallucinations occurred transiently in patients with pre-existing eye disease when infection, intoxication, or physical debilitation compromised brain function; equally, visual hallucinations occurred in patients with pre-existing brain disease as their vision deteriorated. De Ajuriaguerra viewed the cause of visual hallucinations as a continuum of brain and eye contributions rather than a series of discrete syndromic entities. In delirium tremens the brain was primarily responsible with little contribution from the eye; in CBS the eye and brain carried equal weight as factors; in post-surgical eye patching, the eye was more important than the brain. In retaliation, de Morsier published his major work on CBS 3 years after retirement.Citation28 This was a scholarly review of the classical literature, including a facsimile of the two key pages in Bonnet's 18th-century work. However, de Morsier was more concerned with defending his original definition than appraising the emerging eyebrain model, and the damage had been done. For the next two decades, CBS led a parallel existence in the literature, joined in the 1980s by a third definition.

Classical phenomenological syndromes

Perhaps obscured by later controversy surrounding the role of the eye, little attention was paid to key shifts in the approach to visual hallucinations instituted in 1936 by de Morsier, L'Hermitte, and de Ajuriaguerra. For an earlier generation of clinicians, differences in the clinical significance of visual illusions and visual hallucinations had been less absolute. Furthermore, visual hallucinations had not been a single pathological symptom - there had been several distinct types of visual hallucination based on phenomenological characteristics such as their content, form, and emotional associations. The hope of early 20th-century clinicians was that a specific hallucination phenomenology might indicate a specific clinical condition. For example, de Clérambault compared the neuropsychiatrie manifestations of chloral hydrate, alcohol, and cocaine, and found in the visual domain, specific to chloral hydrate, 20- to 30-cm hallucinations of writing, miniature landscapes, or figures projected onto a surrounding wall.Citation29 Some of these early phenomenological syndromes are described below, together with their modern vestiges.

The syndrome of Lilliputian hallucinations

Shortly after his election to the Société MédicoPsychologique by de Clérambault in 1909,Citation30 Raoul Leroy presented a paper concerning multiple small, colored figures associated with a pleasant affect.Citation31 de Clérambault pointed out that his chloral hydrate patients had been indifferent rather than amused by the phenomena, and that giant hallucinations were also found. Apart from the published proceedings of a meeting the following year,Citation32 Leroy deferred to de Clérambault and wrote no further on the topic for a decade. In the 1920s, he published a series of accounts in both the French and English literature, building on his original observations.Citation33-Citation36 His syndrome of Lilliputian hallucinations consisted of:

[...] small people, men or women of minute or slightly variable height; either above or accompanied by small animals or small objects all relatively proportionate in size, with the result that the individual must see a world such as created by Swift in Gulliver. These hallucinations are mobile, coloured, generally multiple. It is a veritable Lilliputian vision. Sometimes it is a theatre of small marionettes, scenes in miniature which appear to the eyes of the surprised patient. All this little world, clothed generally in bright colours, walks, runs, plays and works in relief and perspective; these microscopic visions give an impression of real life.Citation35

In a concession to de Clérambault, Leroy now noted the hallucinations were only pleasurable in typical cases, contrasting with delirious hallucinations which were unpleasant, one state often following the other in the same patient.Citation36 He also added that Lilliputian hallucinations were silent, although were occasionally associated with Lilliputian voices.Citation35 The syndrome was initially described as specific to alcohol or drug-related toxicity, but later examples were given of infective and neurodegenerative causes. Although the syndrome is not referred to today, elements were incorporated into Damas-Mora et al's redefinition of CBS (see below).

Zoopsia

When Leroy contrasted his syndrome with the unpleasant visual hallucinations of delirium, he was indirectly referring to the long-recognized association of fear with visual hallucinations in the context of delirum tremens. These hallucinations could be swarms of small animals (eg, ants, beetles or mice, etc) or isolated groups of larger animals (eg, tigers, elephants, birds, and dogs) and, in the early 20th century, were referred to as zoopsia. Morel produced an account of how the species of animal hallucinated depended on the distance of the surface on which it was projected - mice if 1 metre, pigeons if 2 metres, cats and rabbits if 3 metres, and so forth.Citation37 de Morsier argued against the use of the term as it implied an alcoholrelated etiology, whereas, in fact, animal hallucinations were found in a range of conditions.Citation24 Today, 51 % of patients with visual hallucinations in delirium tremens describe animal hallucinations; however, they are surpassed by figure (82 %) and object (61 %) forms.Citation38 Similar relative frequencies are found in PD.Citation39

Simple versus complex

As outlined above, the early 20th-century view of the visual system was of a broad division into crude visuosensory and elaborated visuopsychic functions. This fitted well with the simple/complex hallucination dichotomy found in clinical and physiological stimulation studies (see ref 40 for a review). By the 1930s, the major neurological textbooks considered simple hallucinations as localizing signs for lesions in the visuosensory cortex, and complex hallucinations as localizing signs for lesions in the visuopsychic cortex and its connections to the temporal lobe. The idea fell out of favor as it became clear that both simple and complex hallucinations were associated with lesions in either location or outside the brain itself in the anterior visual pathways and eye.Citation40 Furthermore, it was unclear on what grounds hallucinations traditionally considered simple (eg, colored stars, leaping flames, or floating bubbles) differed from hallucinations considered complex (eg, faces or figures) as both experiences were fully formed percepts.Citation40 Vestiges of the simple/complex dichotomy survive to the modern era, complexity being a feature of the redefined CBS and simple phenomena, variously named photopsias or phosphenes,Citation41 studied as a separate class of pathological visual perceptual experience (see for example ref 42).

Heinrich Klüver and hallucinatory constants

In studying the visual experiences associated with mescaline, Heinrich Klüver (1897-1979) identified three stereotyped phenomenological patterns which helped inform clinical studies.Citation43 The first related to geometrical patterns (form-constants) which he divided into four classes: (i) grating, lattice, checkerboard; (ii) cobweb; (iii) tunnel, funnel; (iv) spiral. The second related to the perceptual reduplication of objects (polyopia) and changes in perceived size or shape, a syndrome he tentatively linked to visual-vestibular interactions. The third related to changes in the composition of objects with displacements or rearrangements of object features. He argued that the three symptom patterns were found in a range of clinical disorders and reflected undefined neurobiological mechanisms. Although it never developed into a clinical classificatory scheme, the importance of the work is Klüver's Gestalt psychological perspective, viewing visual hallucinations as one of several variants of visual perceptual experience, a position entirely consistent with emerging neuroscientific evidence (see below).

Visual hallucinatory syndrome: present

Today's clinical approach to visual hallucinations is very much as it was in 1936, visual hallucinations being conceived as a unitary pathological symptom distinct from illusions. De Morsier's convention of defining visual hallucinatory syndromes by the neurological and psychiatric context in which the hallucinations are found is still followed for many conditions (eg, PD, DLB, or peduncular lesions). However, with no consensus as to the cause of CBS hallucinations, in the 1980s a novel approach was formulated that looked back to the classical phenomenological tradition.

Phenomenological Charles Bonnet syndrome

Until the 1980s, the CBS eponym and its surrounding debate remained entirely within the French neurological and psychiatric literature. However, in 1982, two groups of British psychiatrists, by introducing the syndrome to a wider international audience, initiated the modern era of visual hallucinatory syndromes.Citation44,Citation45 One group, Berrios and Brook, presented a history of CBS in preparation for a survey of visual perceptual problems in the elderly published 2 years later.Citation46 The other, Damas-Mora et al, wanted to raise awareness of the syndrome to “obviate mistaken psychiatric diagnosis.” Through translated extracts from the classical French literature, Damas-Mora et al abstracted core phenomenological features including hallucination content (simple and complex forms), their onset and temporal evolution, duration, relation to insight and, echoing Leroy's Lilliputian syndrome, their association with a pleasant emotional tone. However, DamasMora et al's most important contribution was the implicit recognition that there might be more than one type of visual hallucination and that pure clinical forms might be revealed by excluding certain disorders. For them, cognitive impairment suggestive of dementia, secondary delusions suggestive of psychosis and unpleasant distorted experiences suggestive of delirium were inconsistent with CBS hallucinations. This focus on phenomenology distanced CBS from the etiological debate, a move completed in 1989 by two American psychiatrists, Gold and Rabins,Citation47 who argued that the syndrome should describe a particular phenomenology until such time as the underlying pathophysiology became clear. Like the Capgras syndrome related to brain lesions, schizophrenia, and affective disorders, CBS could relate to a range of disorders of the eye, brain, or metabolism. Refining DamasMora et al's core phenomenological features and exclusions, Gold and Rabins presented a set of novel diagnostic criteria focussing on complex hallucinations and removing the requirement of a pleasant emotional tone. They also added that hallucinations in other modalities should not be present, a feature that had been noted before (eg, in the Lilliputian syndrome and the L'Hermitte and de Ajuriaguerra 1936 case series), but had never been suggested as a diagnostic criterion. It is the Gold and Rabins CBS that is used in the current psychiatric literature.

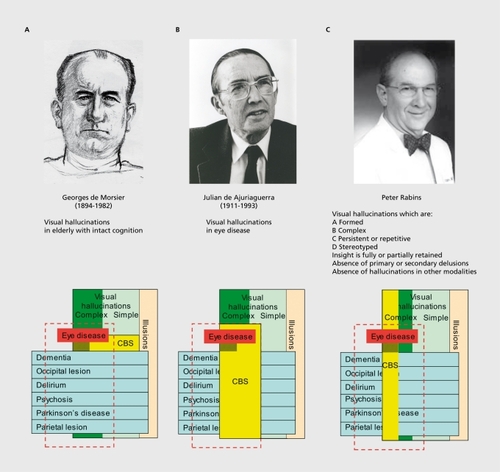

The Charles Bonnet syndromes

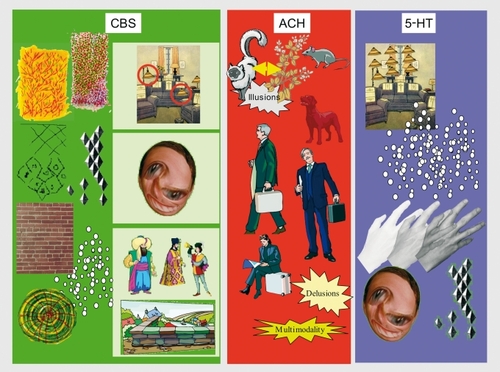

Gold and Rabins' definition leaves clinicians with a choice of three CBSs, illustrated in For de Morsier (Figure 1a), CBS referred to a specific neurodegenerative condition and bore no relation to eye disease. For de Ajuriaguerra (Figure 1b), CBS was the intersection of visual hallucinations and eye disease. For Gold and Rabins (Figure 1c), CBS was a specific class of complex visual hallucination divorced from clinical context. More recent definitions are hybrids (eg, Menon et al use lb and lc In combinationCitation48). Although some patients are classified as CBS by all three schemes (the darkened CBS subregion), the majority that meet diagnostic criteria for one scheme will not do so for another. Thus studies using eye disease to define CBS (1b) may Include patients with auditory hallucinations and delusions that would be excluded from de Morsier's CBS (1a) or the phenomenological CBS (1c). In contrast, studies using phenomenological CBS (1c) may include patients without eye disease, a logical impossibility in terms of CBS (lb) which is defined by eye disease. Clearly, further advance is hindered rather than helped by these concurrent traditions; but without an understanding of the underlying cause of visual hallucinations it is unclear which of the schemes to choose. All have clinical utility, but none have resulted in an understanding of how to investigate, treat, or manage visual hallucinations across the range of clinical contexts. Indeed, one might argue that patients with visual hallucinations today fare little better than those of 70 years ago.

Portrait of de Morsier reproduced with permission of the Centre d'iconographie Genevoise, coll. BPU University of Geneva. Photo of de Ajuriaguerra reproduced with permission of the University Hospital of Geneva. Photo of Peter Rabins reproduced with permission of Dr Rabins.

Current therapeutic options

No large-scale treatment studies of visual hallucinations have yet been reported, evidence for the various drug classes advocated being largely based on case report literature. The general consensus is that response to a given medication class varies from patient to patient, an observation that may relate to the differing clinical contexts that give rise to visual hallucinations. Table III outlines treatment approaches that have been reported as successful in some patients. In those with eye disease, reassurance may be the only treatment required, with surgical ophthalmic interventions improving hallucinations in some cases (see ref 48 for review). In AD, the improvement of acuity through provision of appropriate glasses may be enough to reduce hallucinations.Citation49 Antiepileptic medication can be effective for hallucinations related to visual pathway infarctsCitation50 or eye disease.Citation51 Both typical and atypical antipsychotics have been tried in patients with eye disease with varying success (see ref 48 for review). Cholinesterase inhibitors may improve hallucinations, particularly in patients with cognitive impairment.Citation52 Serotonin (5-HT)3 antagonists have been effective in treating visual hallucinations in both PDCitation53 and eye disease,Citation54 although cisapride has been withdrawn in many countries. Acetazolamide increases cerebral blood flow, has antiepileptic properties, reduces intraocular pressure, and improves visual hallucinations in the context of migraine aura status.Citation55 Finally, de Ajuriaguerra reported that visual hallucinations in a subset of patients with dementia responded to the arousing effects of methylphenidate hydrochloride (Ritalin).Citation27

Table III. Treatment approaches. 5-HT, serotonin; CNS, central nervous system

Neurophenomenological syndromes: the future

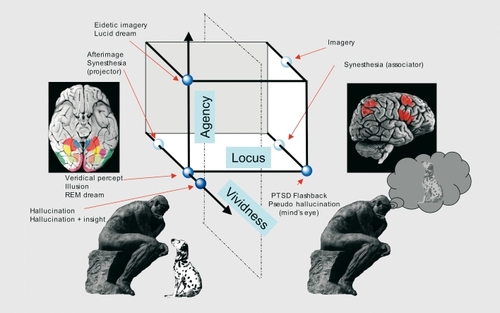

Our current approach to visual hallucinatory syndromes remains heavily influenced by the 1936 formulation of visual hallucinations as a unitary pathological symptom, distinct from illusions, with content of little significance. However, recent advances in perceptual neuroscience question these core assumptions. Imaging studies of the visual system have identified activations in occipital, temporal, limbic, and parietal cortices, each with a relative specialization for a range of visual attributes (see ref 14 for review of areas relevant to visual hallucinations). The conscious experience of seeing a visual attribute present in the world around us (referred to here as a veridical percept) is linked to activity within such specialized visual areas - activity within an area greater when its specialized attribute is perceived compared with when It Is not.Citation56-Citation58 For example, the veridical percept of a moving stimulus Is associated with a larger response In motion specialized cortex than is evoked by the same stimulus when it is not perceived.Citation56 Whether this increment in response marks activity that Is, In itself, sufficient for the conscious experience of motion is disputed (see ref 59 for overview of the debate). Visual hallucinations (referring here to externalized percepts of visual attributes that are not present in the world around us), are associated with spontaneous activations of the same specialized visual areas, the content of a hallucination being defined by the location of the spontaneous activity.Citation60 Thus, the hallucination of an object is associated with spontaneous activity In object-specialized cortex, the hallucination of a face with spontaneous activity in face-specialized cortex, and so forth. Activity Is found In specialized visual areas both when insight is present (pseudohallucinations in one sense of the term) and when it is not.Citation61 The visual illusion disorders encountered clinically (eg, metamorphopsia and palinopsia - see ref 62 for a review) have not been studied extensively with neuroimaging; however, it is likely that these experiences also relate to activity within specialized visual cortex, as nonclinical visual illusions (eg, Kanizsa figures) activate the same areas.Citation63,Citation64 A recent case study of facial metamorphopsia is consistent with this view.Citation65 Afterimages,Citation66 synesthetic experiences,Citation67 and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep,Citation68 are all associated with activity increases in specialized visual areas. In contrast, visual imagery (visual perceptual experiences in the “mind's eye”) seems to have a different neurobiological substrate (see, for example, ref 69 in relation to color). Although specialized visual areas may be Involved In Imagery, the predominant activations are found In the frontal and parietal lobes,Citation70 with feedback from these regions to the visual cortex.Citation71

displays visual perceptual experiences on three phenomenological axes, one related to their perceptual locus (external or in the mind's eye), a second to the sense of agency or volitional control the subject has over them, and a third to their vividness. Veridical percepts, visual hallucinations (with and without insight), visual illusions, and visual afterimages are all located externally, and are devoid of a sense of agency but vary in terms of their vividness. For example, visual hallucinations of colour are often described as hyperintense (hyperchromatopsiaCitation62), while afterimages are typically vague. In contrast, visual imagery appears in the mind's eye and is entirely under volitional control. Other visual perceptual phenomena have mixed properties. Eidetic imagery and lucid dreams are external and vivid but under volitional control, pseudohallucinations (in the sense of experiences occurring in the mind's eye) lack a sense of agency, as do post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) flashback phenomena. Synesthetes also lack a sense of agency over their synesthetic experiences, but fall into two groups, one experiencing the phenomena externally (projectors), the other in the mind's eye (associators).Citation72 Although imaging evidence is lacking for many of these visual perceptual phenomena, a clear and striking pattern emerges for those that have been studied, the combined phenomenological and neurobiological approaches resulting in what I have termed a neurophenomenological classification.Citation14 From a neurobiological perspective, the phenomenal space is divided into two broad regions (left and right of the dotted vertical plane in Figure 2). The predominant brain activation associated with experiences to the left of the figure (perceived externally) lies within specialized visual areas. In contrast, the predominant brain activation associated with experiences to the right of the figure (in the mind's eye) lies within frontal and parietal regions. Thus, a veridical percept of motion,Citation56 an illusion of motion,Citation63 and an afterimage of motionCitation66 are all linked to activity within motion-specialized cortex. In contrast, imagery of motion involves predominantly frontal activations.Citation73 Synesthetic visual experience has also been linked to activity within specialized visual cortex,Citation67 although it is not clear whether this is the case for both projectors and associators.

Emerging visual perceptual syndromes

The various visual phenomena illustrated in Figure 2 are classified within our current psychiatric and philosophical taxonomies as distinct entities, differences between them based on their relation to external objects and to insight, with little attention paid to their content. Thus, a face hallucination is considered a distinct class of experience from a face illusion in a cloud formation, but not from the hallucination of a landscape. Yet, viewed from a neurophenomenological perspective, the same perceptual experiences are classified in an entirely different way. Here, the face illusion and hallucination are considered to be closely related, both involving the same cortical area, but are distinct from the landscape hallucination which involves a different area. In the neurophenomenological classification, the content of perceptual experience becomes of central importance while traditional distinctions between illusions and hallucinations are de-emphasized. This is not to say that veridical percepts, illusions, and hallucinations of a given visual attribute are identical in terms of the underlying neural circuitry within a specialized area. However, it is clear is that these traditionally distinct experiences are more closely related than previously suspected.

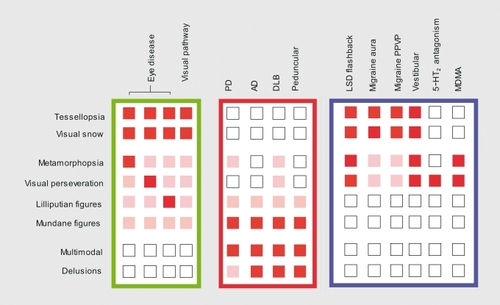

The neurophenomenological perspective undermines key shifts in emphasis in the approach to visual hallucinations and their syndromes instituted in 1936. In neurobiological terms, visual hallucinations are not unitary phenomena, different contents pointing to different cortical loci, and are not distinct from illusions. Neurophenomenological building blocks construct syndromes that have been obscured in our traditional classificatory systems that are perhaps now more appropriately termed visual perceptual syndromes than visual hallucinatory syndromes. shows a range of visual perceptual symptoms cross-tabulated with their associated conditions and color-coded to reflect the relative frequency of each symptom within those patients that have visual perceptual pathology. Three syndromes emerge that appear to be distinct both in their pattern of content and the fact that they remain largely independent - patients with one syndrome rarely developing the same mixture of visual symptoms as found in another. One syndrome (prototypical disorder macular disease-see ref 74) consists of a range of simple phenomena including tessellopsia (brickwork and lattice patterns)Citation62 and multiple dots (visual snow). Although the simplest of these phenomena may have their origins in aberrant retinal firing (eg, flashes or sparks), they can also be elicited by direct stimulation of the visual pathways and cortexCitation41 and, given this ambiguity, it seems reasonable to keep them within the classificatory scheme at present. The simple phenomena as a whole are associated to varying degree with more complex symptoms forming subsyndromes.Citation74 One subsyndrome consists of visual perseveration (an object or object feature remaining fixed in retinal co-ordinates as the eye moves), delayed palinopsia (an object or object feature returning to the field of view after a delay) and the appearance of hallucinations in the peripheral visual field. Another subsyndrome consists of faces, typically grotesque with prominent features and a cartoon or sketch-like quality. The third subsyndrome is reminiscent of Leroy's Lilliputian hallucinations. Each of these subsyndromes seems to relate to pathological activity in a different cortical locus, the first to the parietal lobe, the second to the superior temporal sulcus, and the third to the anterior ventral temporal lobe.Citation74 When other causes of visual hallucinations have been excluded, these symptoms occur without hallucinations in other modalities and without delusions. This syndrome is the Gold and Rabins CBS, broadened to include simple hallucinations and illusions (caricatured in CBS) and is found in both eye diseaseCitation75 and pathology of the visual pathways.Citation50,Citation76-Citation78 In 1973, the American neur ophthalmologist David Cogan hypothesized that such phenomena result from the release of visual cortical activity following the loss of visual inputs.Citation79 Although today release is perhaps better termed deafferentation (see ref 80 for updated neurophysiology), there is much indirect evidence to support the view (eg, an increase in the risk of CBS with greater visual lossCitation81-Citation83). However, Terson's 1920s critique of the ocular theory remains as relevant today as it was when first mooted. Deafferentation alone fails to account for why only a small proportion of ophthalmic patients experience visual hallucinations.

The second syndrome (prototypical disorder PD - see refs 39,84,85) differs from the first in the conspicuous absence of simple hallucinations. Patients experience illusions and fully formed hallucinations, typically of mundane figures or animals (caricatured in Figure 4 Ach). The visual symptoms are often associated with extra-campine and multimodality hallucinations and delusional elaboration. AD,Citation86,Citation87 DLB,Citation88 and peduncular lesionsCitation89 are associated with a similar syndrome which seems to relate to ascending brainstem neurotransmitter dysfunction, particularly in the cholinergic systemCitation14 (see ref 90 for review of cholinergic hypothesis). The third syndrome (prototypical disorder LSD flashbackCitation91 - now hallucinogen persisting perception disorder [HPPD]Citation92) consists of tessellopsia, visual snow, palinopsia, polyopia (multiple copies of an object) and metamorphopsia (caricatured in Figure 4, 5-HT). Patients rarely experience complex visual hallucinations, delusions, or hallucinations in other modalities. The same spectrum of disorders is described in the classical peripheral and central vestibular lesion literature,Citation93 migraine aura, and migraine aura status (persistent positive visual phenomena),Citation94,Citation95 MDMA,Citation96 and 5-HT2 antagonism.Citation97 Although the underlying mechanism of this syndrome is unclear, many of the conditions in which it occurs are linked to the serotonergic system.

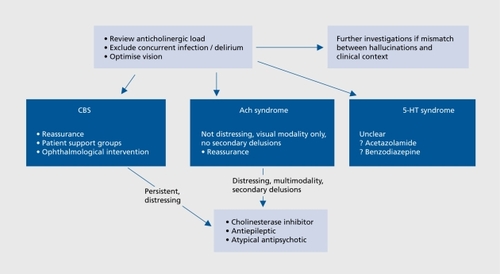

outlines a treatment algorithm for the three visual perceptual syndromes. For each, it is important to: i) review medication to minimize anticholinergic load; ii) consider whether the syndrome may have been precipitated by concurrent infection (often a urinary tract infection in the elderly); and iii) if necessary, optimize vision. The question of whether to investigate depends largely on the match between the syndrome and clinical context. Hallucinations of a familiar dog in a patient with Parkinson's disease would not warrant further investigation, but hallucinations of grid patterns confined to one hemifield might prompt neuroimaging of the visual pathways and cortex. Similarly, prolonged hallucinations of whispering figures in a patient with macular disease might prompt a psychiatric review, whereas a brief hallucination of an Edwardian tea party would not. CBS may be treated with the reassurance of a likely resolution with time, although patients may be warned that symptoms can re-occur following further visual deterioration. For anticholinergic syndrome phenomena that are not distressing, restricted to the visual modality, and not associated with persistent secondary delusions, patients may be managed with reassurance, although the experiences are likely to persist and progress. For CBS phenomena that persist and are distressing or Ach syndrome phenomena that are distressing, multimodal, or have persistent delusions, medication can be considered, the class is chosen depending on clinical context. Cholinesterase inhibitors would be a logical first choice for patients with cognitive impairment, while antipsychotics may be appropriate for those with pronounced delusions. Management of the 5-HT syndrome is unclear; however, acetazolamide or benzodiazepines may have a role in the specific contexts of migraine aura statusCitation55 and HPPD.Citation91

Conclusions

The legacy of past visual hallucinatory syndromes has been confusion and obfuscation, questioning the wisdom of another classificatory scheme. Why add further complication to an already complex field? The answer lies in the possibility that the neurophenomenological approach, and syndromes derived from it, reveal features hidden in our traditional taxonomies by bringing us closer to the underlying pathophysiology. The emerging neurobiological insights may ultimately fulfil the early 20th-century aspiration that specific hallucination phenomenology points to a specific etiology. The evidence presented above tentatively links each syndrome to dysfunction within afferent, cholinergic, or serotonergic visual circuitry; however, this will be an oversimplification. Furthermore, even if correct, visual perceptual pathology related to pure deafferentation, pure cholinergic, or pure serotonergic dysfunction is likely to be the exception rather than the rule in routine clinical practice. Yet despite this undoubted weakness, the identification of distinctive patterns of visual perceptual pathology may prove to be the key to understanding the investigation and treatment of the experiences. How the relative contributions of the differing mechanisms can be assessed are questions for the future. For now we must be content with the possibility that insights from perceptual neuroscience will take us past the 70 years of controversy and revitalise visual hallucinatory syndromes for future generations of clinicians.

Selected abbreviations and acronyms

| CBS | = | Charles Bonnet syndrome |

| PD | = | Parkinson's disease |

| AD | = | Alzheimer's disease |

| HPPD | = | hallucinogen persisting perception disorder |

| PPVP | = | persistent positive visual phenomena |

Supported by a Wellcome Trust Clinician Scientist Fellowship.

REFERENCES

- de MorsierG.Les automatismes visuels. (Hallucinations visuelles rétrochiasmatiques).Schweizerische Medizinische Wochenschr.193666700703

- L'HermitteJ.De AjuriaguerraJ.Hallucinations visuelles et lésions de l'appareil visuel.Ann Médico-Psychologiques.193694 i321351

- CataniM.ffytcheDH.The rises and falls of disconnection syndromes.Brain.20051282224223916141282

- HeuyerG. de ClérambaultG.Encéphale.195039413439

- EyH.Une théorie méchaniciste: la doctrine de G. de Clérambault.Études Psychiatriques. Paris: Desclée de Brouwer1948

- de MorsierG.Le Mécanisme des hallucinations.Ann Médico-Psychologiques.193088365389

- de MorsierG.Les Hallucinations: étude Oto-neuro-ophtalmologique.Rev Oto-Neuro-Ophtalmol.193816244352

- ffytcheDH.CataniM.Beyond localisation: from hodology to function.Phil Trans R Soc Lon B.200536076777915937011

- SeguinEC.A clinical study of lateral hemianopsia.J Nerv Ment Dis.188613445454

- ShippS.Corticopulvinar connections of areas V5, V4, and V3 in the macaque monkey: a dual model of retinal and cortical topographies.J Comp Neurol.200143946949011596067

- StarobinskiJ.Georges de Morsier (1894-1982).Gesnerus.198340335338

- UchidaH.SuzukiT.TanakaKF.WatanabeK.YagiG.KashimaH.Recurrent episodes of perceptual alteration in patients treated with antipsychotic agents.J Clin Psychopharmacol.20032349649914520127

- UchidaH.SuzukiT.WatanabeK.YagiG.KashimaH.Antipsychoticinduced paroxysmal perceptual alteration.Am J Psychiatry.20031602243224414638603

- ffytcheDH.Visual hallucinations and the Charles Bonnet Syndrome.Curr Psychiatr Reports.20057168179

- CollertonD.PerryE.McKeithI.Why people see things that are not there: a novel perception and attention deficit model for recurrent complex visual hallucinations.Behav Brain Sci. 200528737757; discussion 757-794.16372931

- FlournoyT.Le cas de Charles Bonnet: hallucinations visuelles chez un vieillard opéré de la cataracte.Arch Psychol. (Geneva).19021123

- NaviIIeE.Hallucinations visuelles a l'état normal.Arch Psychol. (Geneva).190981-8; 200-206

- de MorsierG.Les hallucinations visuelles diencéphaliques. II.Psychiatr Clin (Basel).196922322514897695

- MoraxV.Sur les hallucinations visuelles survenant au cours des altérations rétiniennes.Progres Med.192250652654

- TrucH.Phantopsies ou fantasmagories visuelles d'origine oculaire.Annales & Oculist.1925162649655

- BrunerieA.CocheR.Sur trois cas d'hallucinations visuelles chez des cataractes.Ann Médico-Psychologiques.193694166171

- OrmondAW.Visual hallucinations in sane people.BMJ.19252376379

- TersonA.Hallucinations visuelles chex des ophtalmopathes.Annales d'Oculist.1930168815825

- de MorsierG.Réponses.Rev Oto-Neuro-Ophtalmol.193917218240

- HecaenH.GarciaBadaracco J.Les hallucinations visuelles au cours des ophthalmopathies et des lesions des nerfs et du chiasma optiques.L'Evolution Psychlat.1956157179

- de AjuriaguerraJ.GarroneG.Désafférentation partielle et psychopathologie. In: de Ajuriaguerra J, edi.Désafférentation expérimentale et clinique. Geneva: Georg196591157

- BurgermeisterJJ.TissotR.de AjuriaguerraJ.Les hallucinations visuelles des ophthalmopathes.Neuropsychologic.19653938

- de MorsierG.Le syndrome de Charles Bonnet: hallucinations visuelles des vieillards sans déficience mentale.Annales Médico-Psychologiques.1967125677702

- de ClérambaultG.Du diagnostic différentiel des délires de cause chloralique.Ann Médico-Psychologiques.1909;191067;68220-365;33-192248-389;192-215

- Société-Médico-Psychologique. Séance du 26 Avril 1909.Ann Médico-Psychologiques.1909675859

- LeroyR.Les hallucinations lilliputiennes.Ann Médico-Psychologiques.190967278289

- LeroyR.Un cas d'hallucinations lilliputiennes.Bull Société Clin Médecine Mentale.1910132135

- LeroyR.FursacRd.Les hallucinations lilliputiennes.Encéphale.192015189192

- LeroyR.Le syndrome des hallucinations lilliputiennes.Encéphale.192116504510

- LeroyR.The syndrome of Lilliputian hallucinations.J Nerv Ment Dis.192256325333

- LeroyR.The affective states in Lilliputian hallucinations.J Ment Sci.192672179186

- MorelF.Hallucination et champ visuel.Ann Médico-Psychologiques.193795742757

- PlatzWE.OberlaenderFA.SeidelML.The phenomenology of perceptual hallucinations in alcohol-induced delerium tremens.Psychopathology.1995282472558559948

- FénelonG.MahieuxF.HuonR.ZieglerM.Hallucinations in Parkinson's disease: prevalence phenomenology and risk factors.Brain.200012373374510734005

- WeinbergerLM.GrantFC.Visual hallucinations and their neuro-optical correlates.Arch Ophth Chicago.194023166199

- CelesiaGG.Positive spontaneous visual phenomena. In: Celesia G G, editor.Handbook of Clinical Neurophysiology: Disorders of Visual Processing. Elsevier2005353370

- BrownGC.MurphyRP.Visual symptoms associated with choroidal neovascularization. Photopsias and the Charles Bonnet syndrome.Arch Ophthalmol.19921101251-61381580

- KlüverH.Mescal and Mechanisms of Hallucinations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press1966

- Damas-MoraJ.Skelton-RobinsonM.JennerFA.The Charles Bonnet Syndrome in perspective.Psychol Med.1982122512617100349

- BerriosGE.BrookP.The Charles Bonnet syndrome and the problem of visual perceptual disorders in the elderly.Age Ageing.19821117237041567

- BerriosGE.BrookP.Visual hallucinations and sensory delusions in the elderly.Br J Psych.1984144662664

- GoldK.RabinsPV.lsolated visual hallucinations and the Charles Bonnet syndrome: a review of the literature and presentation of six cases.Comprehensive Psychiatry.19893090982647403

- MenonGJ.RahmanI.MenonSJ.DuttonGN.Complex visual hallucinations in the visually impaired: the Charles Bonnet Syndrome.Surv Ophthalmol.200348587212559327

- ChapmanFM.DickinsonJ.McKeithI.BallardC.Associations among visual hallucinations, visual acuity and specific eye pathologies in Alzheimers disease.Am J Psychiatry.19991561983198510588415

- LanceJW.Simple formed hallucinations confined to the area of a specific visual field defect.Brain.197699719734828866

- PauligM.MentrupH.Charles Bonnets syndrome: complete remission of complex visual hallucinations treated by gabapentin.J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry.20017081381411430294

- BurkeWJ.RoccaforteWH.WengelSP.Treating visual hallucinations with donepezil.Am J Psychiatry.19991561117111810401470

- ZoldanJ.FriedbergG.LivnehM.MelamedE.Psychosis in advanced Parkinsons disease: treatment with ondansetron, a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist.Neurology.199545130513087617188

- RanenNG.PasternakRE.RovnerBW.Cisapride in the treatment of visual hallucinations caused by vision loss: the Charles Bonnet syndrome.Am J Geriatr Psychiatry.1999726426610438699

- HaanJ.SluisP.SluisLH.FerrariMD.Acetazolamide treatment for migraine aura status.Neurology.2000551588158911094126

- ZekiS.ffytcheDH.The Riddoch syndrome: insights into the neurobiology of conscious vision.Brain.199812125459549486

- MoutoussisK.ZekiS.The relationship between cortical activation and perception investigated with invisible stimuli.Proc Nati Acad Sci USA.20029995279532

- PinsD.ffytcheDH.The neural correlates of conscious vision.Cereb Cortex.20031346147412679293

- BlockN.Two neural correlates of consciousness.Trends Cogn Sci.20059465215668096

- ffytcheDH.HowardRJ.BrammerMJ.DavidA.WoodruffP.S.WilliamsThe anatomy of conscious vision: an fMRI study of visual hallucinations.Nature Neurosci.1998173874210196592

- AdachiN.WatanabeT.MatsudaH.OnumaT.Hyperperfusion in the lateral temporal cortex, the striatum and the thalamus during complex visual hallucinations: single photon emission computed tomography findings in patients with Charles Bonnet syndrome.Psychiatry Clin Neurosci.200054157-6210803809

- ffytcheDH.HowardRJ.The perceptual consequences of visual loss: positive pathologies of vision.Brain.19991221247126010388791

- ZekiS.WatsonJDG.FrackowiakRSJ.Going beyond the information given: the relation of illusory visual motion to brain activity.Proc R Soc Lon B.1993252215222

- ffytcheDH.ZekiS.Brain activity related to the perception of illusory contours.Neuroimage.199631041089345481

- HeoK.ChoYJ.LeeSK.ParkSA.KimKS.LeeBI.Single-photon emission computed tomography in a patient with ictal metamorphopsia.Seizure.20041325025315121135

- TootellRBH.ReppasJB.DaleAM.et al.Visual motion aftereffect in human cortical area MT revealed by functional magnetic resonance imaging.Nature.19953751391417753168

- NunnJA.GregoryLJ.BrammerM et al.Functional magnetic resonance imaging of synesthesia: activation of V4/V8 by spoken words.Nat Neurosci.2002537137511914723

- BraunAR.BalkinTJ.WesentenNJ et al.Regional cerebral blood flow throughout the sleep-wake cycle. An H2(15)0 PET study.Brain.1997120(Pt 7)117311979236630

- HowardRJ.ffytcheDH.BarnesJ.et al.The functional anatomy of imagining and perceiving colour.Neuroreport.19989101910239601660

- GanisG.ThompsonWL.KosslynSM.Brain areas underlying visual mental imagery and visual perception: an fMRI study.Brain Res Cogn Brain Res.20042022624115183394

- MechelliA.PriceCJ.FristonKJ.IshaiA.Where bottom-up meets topdown: neuronal interactions during perception and imagery.Cereb Cortex.2004141256126515192010

- DixonMJ.SmilekD.MeriklePM.Not all synaesthetes are created equal: projector versus associator synaesthetes.Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci.2004433534315535169

- BinkofskiF.AmuntsK.StephanKM et al.Broca's region subserves imagery of motion: a combined cytoarchitectonic and fMRI study.Hum Brain Mapp.20001127328511144756

- SanthouseAM.HowardRJ.ffytcheDH.Visual hallucinatory syndromes and the anatomy of the visual brain.Brain.20001232055206411004123

- TeunisseRJ.CruysbergJR.HoefnagelsWH.VerbeekAI.ZitmanFG.Visual hallucinations in psychologically normal people: Charles Bonnet's syndrome.Lancet.19963477947978622335

- KölmelHW.Coloured patterns in hemianopic fields.Brain.19841071551676697153

- KölmelHW.Complex visual hallucinations in the hemianopic field.J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry.19854829383973619

- VaphiadesMS.CelesiaGG.BrigellMG.Positive spontaneous visual phenomena limited to the hemianopic field in lesions of central visual pathways.Neurology.1996474084178757013

- CoganDG.Visual hallucinations as release phenomena.Graefe's Archiv Clin Exp Opthalmol.1973188139-50

- BurkeW.The neural basis of Charles Bonnet hallucinations: a hypothesis.J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry.20027353554112397147

- HolroydS.RabinsPV.FinkelsteinD.NicholsonMC.ChaseGA.WisniewskiSC.Visual hallucinations in patients with macular degeneration.Am J Psych.199214917011706

- TeunisseRJ.CruysbergJR.VerbeekAL.ZitmanFG.The Charles Bonnet syndrome: a large prospective study in the Netherlands.Br J Psychiatry.19951662542577728372

- ScottIU.ScheinOD.FeuerWJ.FolsteinMF.Visual hallucinations in patients with retinal disease.Am J Ophthalmol.200113159059811336933

- BarnesJ.DavidAS.Visual hallucinations in Parkinson's disease: a review and phenomenological survey.J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry.200170727-3311385004

- GrahamJM.GrünewaldRA.SagarHJ.Hallucinosis in idiopathic Parkinson's disease.J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry.1997634344409343119

- HolroydS.Sheldon-KellerA.A study of visual hallucinations in Alzheimer's disease.Am J Geriatric Psychiatry.19953198205

- BallardC.McKeithI.HarrisonR et al.A detailed phenomenological comparison of complex visual hallucinations in dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer's disease.Int Psychogeriatr.199793813889549588

- MosimannUP.RowanEN.PartingtonCE.et al.Characteristics of visual hallucinations in Parkinson disease dementia and dementia with lewy bodies.Am J Geriatr Psychiatry.20061415316016473980

- BenkeT.Peduncular hallucinosis: A syndrome of impaired reality monitoring.J Neurol.20062531561157117006630

- PerryEK.PerryRH.Acetylcholine and hallucinations: disease-related compared to drug-induced alterations in human consciousness.Brain Cognition.199528240258

- AbrahamHD.Visual phenomenology of the LSD flashback.Arch Gen Psychiatry.1983408848896135405

- HalpernJH.PopeHG.JrHallucinogen persisting perception disorder: what do we know after 50 years?Drug Alcohol Depend.20036910911912609692

- SchilderP.The vestibular apparatus in neurosis and psychosis.J Nerv Ment Dis.193378123 SchilderP.The vestibular apparatus in neurosis and psychosis.J Nerv Ment Dis. 137164

- LiuGT.SchatzNJ.GalettaSL.VolpeNJ.SkobierandaF.KosmorskyGS.Persistent positive visual phenomena in migraine.Neurology.1995456646687723952

- KleeA.WillangerR.Disturbances of visual perception in migraine.Acta Neurologica Scandinavica.1966424004145331608

- McGuirePK.CopeH.FahyT.Diversity of psychopathology associated with use of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine ('Ecstasy').Br J Psych.1994165391395

- Ihde-SchollT.JeffersonJW.Mirtazapine-associated palinopsia.J Clin Psychiatry.20016237311411821