Abstract

Contrary to popular belief, sex hormones act throughout the entire brain of both males and females via both genomic and nongenomic receptors. Many neural and behavioral functions are affected by estrogens, including mood, cognitive function, blood pressure regulation, motor coordination, pain, and opioid sensitivity. Subtle sex differences exist for many of these functions that are developmentally programmed by hormones and by not yet precisely defined genetic factors, including the mitochondrial genome. These sex differences, and responses to sex hormones in brain regions and upon functions not previously regarded as subject to such differences, indicate that we are entering a new era in our ability to understand and appreciate the diversity of gender-related behaviors and brain functions.

A diferencia de la creencia popular, las hormonas sexuales actúan sobre todo el cerebro tanto de machos como de hembras mediante los receptores genómicos y no genómicos. Muchas funciones neurales y conductuales están influenciadas por los estrógenos, incluyendo el ánimo, la función cognitiva, la regulación de la presión sanguínea, la coordinación motora, el dolor y la sensibilidad a los opioides. Existen sutiles diferencias por sexo para muchas de estas funciones que están programadas a través del desarrollo por hormonas y por factores genéticos no todavía bien definidos, incluyendo el genoma mitocondrial. Estas diferencias de sexo, y las respuestas a las hormonas sexuales en regiones cerebrales y sobre funciones que antes no se consideraban sujetas a tales diferencias, indican que estamos entrando en una nueva era en nuestra capacidad para comprender y apreciar la diversidad de las conductas relacionadas con el género y las funciones cerebrales.

Contrairement à la croyance populaire, les hormones sexuelles agissent sur tout le cerveau, masculin et féminin, à travers des récepteurs génomiques et non génomiques. Les estrogènes agissent sur de nombreuses fonctions neuronales et comportementales dont l'humeur, les fonctions cognitives, la régulation de la pression artérielle, la coordination motrice, la douleur et la sensibilité aux opioïdes. Il existe des différences subtiles selon le sexe pour un grand nombre de ces fonctions dont le développement est sous dépendance hormonale et sous l'influence de facteurs génétiques non encore précisément définis, comme le génome mitochondrial. Ces différences selon le sexe et les réponses aux hormones sexuelles dans des régions cérébrales et sur des fonctions considérées auparavant comme non concernées par de telles différences, montrent qu'une nouvelle ère de compréhension et d'appréciation de la variété des comportements et des fonctions cérébrales selon le sexe s'ouvre devant nous.

Introduction

Realization that the brain is a target of sex hormones began with studies of reproductive hormone actions on the hypothalamus, regulating not only gonadotropin secretion and ovulation in females but also sex behavior.Citation1 The work of Geoffrey Harris and subsequent pioneers established the connections between the brain and the endocrine system via the hypothalamus and the portal blood vessels that carry releasing factors from the hypothalamus to the pituitary gland.Citation2,Citation3 After the portal blood supply was shown to carry blood from the hypothalamus to the anterior pituitary,Citation2 heroic efforts using hypothalamus tissue from slaughterhouse animals led to the isolation and structural identification of peptidereleasing factors.Citation4,Citation5 The feedback regulation of hypothalamic and pituitary hormones implied the existence of receptor mechanisms for gonadal, adrenal, and thyroid hormones. Then, the identification of cell nuclear hormone receptors in peripheral tissuesCitation6,Citation7 by use of tritiated (3H) steroid and iodinated thyroid hormones led to the demonstration by Don Pfaff, as well as Walter Stumpf, of similar receptor mechanisms in the hypothalamus and pituitary gland.Citation8,Citation9

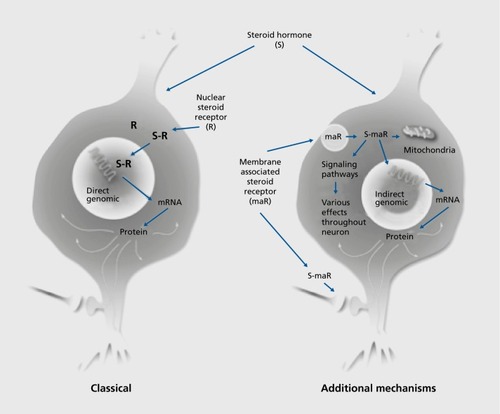

Although the focus at the time was on sexual behavior,Citation1,Citation10 there were other behaviors and neurological states that were known to be influenced by estrogens involving brain regions besides the hypothalamus, including fine motor control, pain mechanisms, seizure activity, mood, cognitive function, and neuroprotection.Citation11 The unexpected discovery of cell nuclear receptor sites for glucocorticoids in the hippocampus, not only of rodents but also monkeys with extension to other species,Citation12 pointed to brain regions other than hypothalamus as targets of circulating hormones. A further serendipitous finding of nuclear estrogen receptors (ERs) in the hippocampusCitation13 also represented a turning point in the realization that not all steroid hormone actions occur via cell nuclear receptors, but rather operate via receptors in other parts of the cell through a variety of signaling pathways ( ).Citation14,Citation15 This is now recognized to be the case for all classes of steroid hormones, including vitamin D, aldosterone, and androgen, as well as estrogens and progestins, to be discussed later in this review.Citation14 First, because structural plasticity of the brain is regulated by hormones, we shall briefly introduce the evolving concepts of plasticity in the adult brain.

Plasticity of the adult brain

Long regarded as a rather static and unchanging organ, except for electrophysiological responsivity, such as long-term potentiation,Citation16 the brain has gradually been recognized as capable of undergoing rewiring after brain damageCitation17 and also able to grow and change, as seen by dendritic branching, angiogenesis, and glial cell proliferation during cumulated experience.Citation18,Citation19 More specific physiological changes in synaptic connectivity were also recognized in relation to hormone action in the spinal cordCitation20 and in environmentally directed plasticity of the adult songbird brain.Citation21 Seasonally varying neurogenesis in restricted areas of the adult songbird brain is recognized as part of this plasticity.Citation22 Indeed, neurogenesis in the adult mammalian brain was initially describedCitation23,Citation24 and later rediscovered in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus.Citation25 Although the existence of adult neurogenesis in the mammalian central nervous system was doubted by some,Citation26 recent evidence clearly proves that the human hippocampus shows significant neurogenesis in adult life.Citation27

Sex hormone actions beyond the hypothalamus

Hippocampus

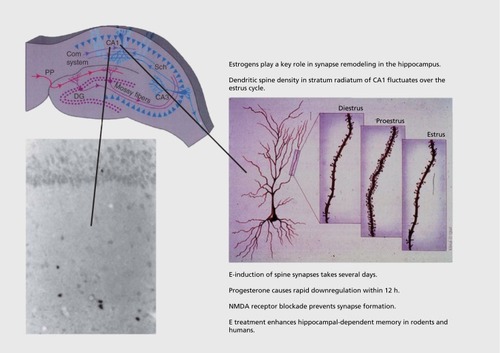

In the original steroid autoradiography studies, a few scattered cells in hippocampus demonstrated strong cell nuclear labeling by 3H estradiol in inhibitory intemeurons.Citation28 Moreover, it was shown that the threshold for eliciting seizure activity in hippocampus was lowest on the day of proestrus when estrogen levels are elevated.Citation29 Moreover, estrogens enhance memory retention of the type involving the hippocampus.Citation30 Using the classical Golgi method, we found cyclic variation in the density of spine synapses on the principal neurons of the CA1 region of the hippocampus, with peak density occurring on the day of proestrus ( ).Citation31 These surprising findings have led to a deeper understanding of mechanisms, as followsCitation32:

(i) Blocking N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors prevents estradiol induction of synapses. Thus, estradiol does not work alone in causing this synapse formation, and the study of underlying mechanisms is revealing some remarkable new aspects not only of hormone action, but also of neuronal plasticity.Citation32

(ii) Estrogen treatment does not induce spine synapses in the adult castrated male hippocampus even though testosterone and dihydrotestosterone do induce spine synapses in the male hippocampus. Paradoxically, male rats treated with aromatase inhibitors at birth, which inhibit defeminization of the brain by endogenous androgen via conversion to estradiol, do respond to estradiol in adulthood with spine synapse induction. Furthermore, androgens are also able to induce spine synapses in the female rat hippocampus (see ref 32 et al).

(iii) The mechanisms implicated in estrogen-induced synapse formation involve interactions among multiple cell types in the hippocampus, as well as multiple signaling pathways. Cholinergic modulation of inhibitory interneurons is involved, and estradiol rapidly and nongenomically stimulates acetylcholine release via ERα on cholinergic terminals in the hippocampus.Citation32 In contrast to the ER story, CA1 pyramidal neurons have ample expression of cell nuclear androgen receptors.Citation33 In the male, these nuclear androgen receptors may play a pivotal role in spine synapse formation, which involves NMDA activity but not cholinergic activity.Citation34 There are also extranuclear androgen receptors with epitopes of the nuclear receptor that are found in the hippocampus in membrane-associated locations in dendrites, spines, and glial cell processes.Citation33 However, the role of nonge nomic forms of androgen receptors in spine synapse formation and other processes is less clear.

(iv) Nongenomic, membrane-associated forms of the classical ER are found in dendrites, synapses, terminals, and glial cell processes (reviewed in ref 32). In the CA1 pyramidal neurons, nongenomic actions of estrogens via phosphatidylinositol 3 (PI3) kinase promote actin polymerization and fllopodia outgrowth to form putative synaptic contacts by dendrites with presynaptic elements. Subsequent PI3 kinase activation via ERs stimulated translation of postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD-95) in dendrites to provide a postsynaptic scaffold for spine synapse maturation. Signaling pathways implicated in these events include LIM kinase (LIMK) and cofilin phosphorylation and PI3 kinase activation, as well as the Rac/Rho signaling system. It is important to note that the cofilin pathway is implicated in spinogenesis in the ventromedial hypothalamus that contributes to activating lordosis behavior.Citation35

(v) Progesterone treatment after estrogen-induced synapse formation causes rapid (12 h) downregulation of spine synapses; moreover, the progesterone receptor antagonist Ru486 blocked the naturally occurring downregulation of estradiol-induced spines in the estrus cycle. Curiously, the classical progestin receptor is not detectable in cell nuclei within the rat hippocampus, but it is expressed in non-nuclear sites in hippocampal neurons, and virtually all of the detectable progestin receptor is estrogen inducible. The mechanism of progesterone action on synapse downregulation is presently unknown.Citation32,Citation36

Estrogen actions throughout the brain

Besides hippocampus, other brain regions demonstrate estrogen-regulated spine synapse formation and turnover,Citation32,Citation37 including the prefrontal cortex (PFC)Citation38 and primary sensory-motor cortex.Citation39 Moreover, there are sex differences that are developmentally programmed as will now be discussed.

Developmental programming of sex differences

Mechanisms

Developmentally programmed sex differences arise not only from secretion of sex hormones during sensitive periods in development but also through contributions of genes on Y and X chromosomes. In females, there is inactivation of one or the other X chromosome,Citation40; moreover, mitochondria derive from the mother, and mitochondrial genes make important contributions to brain and body functions.

In brain, there are few sexual dimorphisms, ie, complete differences between males and females. The sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area (SDN-POA) in the rodent brain comes close,Citation41 and Witelson has described an apparent sex dimorphism in the human brain.Citation42 However, the vast majority of sex differences are far more subtle and involve patterns of connectivity and brain regional differences that are controversial.Citation43

Developmental windows and delayed, lasting effects

The contribution of sex hormones to the male and female phenotype occurs primarily during critical windows of early, perinatal development in which there is a considerable delay between testosterone or estradiol exposure and the emergence of sexually dimorphic traits, suggesting an imprinted “memory” of the hormonal exposure.Citation44 For example, sex differences in the stress-induced remodeling of dendrites and synapses in the hippocampus and PFC emerge during peripubertal sexual maturation.Citation45 The search for molecular pathways that sustain sex differences in the brain revealed several sex-biased genes with markedly different expression levels in males and females at diverse stages of development.Citation46

Epigenetic regulation of gene expression

Parsch and EllegrenCitation46 suggested that sex-specific effects on reproduction drive the rapid evolution of sex-biased genes. Males and females adopt different strategies to cope with environmental challenges. Indeed, the response to stress induces sex-specific effects on brain plasticityCitation36,Citation47,Citation48 and activation of neuronal circuitry,Citation49,Citation50 as well as distinct behavioral phenotypes in males and females.Citation51

Transcriptional regulation helps explain the sex-dependent sensitivity to stressful stimuli and the associated risk of neuropsychiatric disorders in males versus females.Citation51 For example, stress-induced transcriptional response of the immediate early gene Fos is higher in females than in males after acute stress.Citation52 Moreover, handling and acute stress induce markedly different immediate early gene expression activation in male versus female mice, with females showing a stronger hippocampal gene activation than males.Citation53 Furthermore, Nugent et al demonstrated that brain feminization is maintained by the active suppression of masculinization through DNA methylation,Citation54 pointing to epigenetic modifications that promote and maintain sex dimorphic features.

Epigenetics, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, and mental illness

The incidence of mood disorders is 1.5-to-2-fold higher in women than in men.Citation55 Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) has been one of the most studied genes because of its role in neuronal survival and plasticity,Citation56-Citation58 and altered BDNF levels have been associated with altered mental states both in women and in men.Citation59 Estradiol induces BDNF expression, and BDNF mediates some estradiol effects in the hippocampus.Citation32 The discovery of a common single nucleotide polymorphism of the BDNF gene, BDNF Val66Met, led to recognition of subpopulations with differential vulnerability to mood and other disorders and metabolic dysregulation.Citation60 In experimental models with the BDNFMet allele, the estrus cycle critically interacts with the BDNF Val66Met variant to control hippocampal function and the associated behaviors.Citation32

Patterns of gene regulation

A whole-brain transcriptome analysis showed that the gene expression difference between males and females changes over the lifetime and that the greatest expression divergence occurs during the perinatal and peripubertal periods.Citation61 Duclot and KabbajCitation62 used RNA sequencing for a genome-wide characterization of sex differences and estrus cycle influence in the rat medial PFC. They found that the transcriptomal difference between females with high and low ovarian hormone levels was greater than the difference between both female conditions and males. Thus, endogenous fluctuation of gonadal hormones may induce alternative gene networks within the same sex. In nucleus accumbens, male and female mice exposed to the same stressors display different transcriptional regulation, and the transcriptional phenotype of the nucleus accumbens predicts the increased behavioral susceptibility to stress in females versus males.Citation63

Using the bacterial artificial chromosome transgenic mouse (BAC-TRAP) system,Citation64 the messenger RNA from hippocampal CA3 neurons was extracted and subjected to RNA sequencing. The stress-vulnerable CA3 neurons respond differentially to chronic stress in males and females.Citation36 Acute stress produced markedly different transcriptomic profiles in the CA3 neurons, with females showing a larger number of genes up- or downregulated than with males ( ). Moreover, we found that one episode of acute stress dramatically decreased the gene expression changes observed in unstressed female mice during endogenous fluctuation of estradiol levels (see Figure 3). Thus, targeting discrete brain regions paves the way for novel insights into the molecular underpinnings of hormonal actions and sex differences.

![Figure 3. Gene-expression profile generated by RNA sequencing of CA3 pyramidal neurons. (A) Venn diagram depicting the number of genes affected by acute stress in CA3 pyramidal neurons of male and female BAG-TRAP mice. Acute stress induces more genes in females (pink) than in males (blue). The overlap (purple) represents the number of genes commonly changed in males and females. (B) Venn diagram illustrating the number of genes altered during endogenous fluctuation of estradiol levels (high estradiol [proestrus] vs low estradiol [diestrus]) in CA3 pyramidal neurons of female BAG-TRAP mice. Acute stress (green) dramatically decreases the estradiol-biased genes observed in unstressed mice (orange). The overlap (brown) represents the number of genes commonly changed in unstressed and acutely stressed females. BAC-TRAP, bacterial artificial chromosome transgenic mouse; down arrow, downregulated genes; up arrow, upregulated genes.](/cms/asset/fa9538f1-6135-4e57-8735-5a849916575f/tdcn_a_12131069_f0003_oc.jpg)

Sex differences throughout the brain

Sex differences emerge in many brain regions throughout the life course via both genetic and epigenetic mechanisms because of the widespread distribution of nongenomic, as well as genomic, forms of sex hormone receptors. Below, we present some examples, by no means exhaustive, to illustrate both the widespread nature of sex hormone influences but also the unexpectedly widespread nature of subtle sex differences.

Hippocampus response to stressors

Dendrite remodeling

Twenty-one days of chronic restraint stress (CRS) causes apical dendrites of CA3 neurons to retract; these changes do not occur after CRS in female rats.Citation65

Spatial memory

Female and male rats show opposite effects of chronic stress on hippocampal-dependent memory, with males showing impairment and females showing enhancement or no effect.Citation66

Classical conditioning

Exposure of male and female rats to restraint plus intermittent tail shock yields opposite effects on classical eyeblink conditioning, inhibiting it in females and enhancing it in males; in females, this effect is abolished by ovariectomy and is therefore estrogen dependent.Citation67,Citation68 A morphological correlate of this in the hippocampus: acute stress inhibits estrogen-dependent spine formation in CA1 neurons of the hippocampus, whereas the same acute stressors enhance spine density in male CA1 neurons, possibly by increasing testosterone secretion upon which spine formation in the male CA1 is dependent.Citation68

Neonatal masculinization

Neonatal masculinization of females makes them respond positively, like genetic males, to shock stressor.Citation68 Moreover, in females, depending on reproductive status and previous experience, the negative stress effect is altered, eg, it is absent in mothers and virgin females with experience with infants.Citation69

Opioids

Females have a heightened sensitivity to stressCitation70,Citation71 and can show enhanced cognitive performance after stress,Citation72 which may contribute to their accelerated course of addiction. Ten days of chronic immobilization stress in males essentially “shuts off” the opioid system, whereas chronic stress “primes” the opioid system in all females in a manner that would promote excitation and learning processes after subsequent exposure either to stress or an opiate ligand.Citation70,Citation71

Maturational/developmental component

Sex differences in chronic stress effects on dendrite length and branching appear after puberty. Stress in the pubertal transition causes qualitatively similar responses in males and females in hippocampus, PFC, and amygdala; however, after puberty, distinct sex differences in response to chronic stress become evident.Citation45

Sex differences in prefrontal cortex

CRS for 21 days causes neurons in the medial PFC of the male rat to show dendritic debranching and shrinkage.Citation73 These neurons, which project to cortical areas and not to the amygdala, do not show dendritic changes in females. However, neurons that project to the amygdala from the medial PFC undergo dendritic expansion in females but not in males; this expansion in the female is estrogen-dependent, evidenced by ovariectomized females not showing such changes.Citation50 Estrogens and stress also interact in a regionally specific manner in the PFC in that cortically projecting PFC neurons, which show no dendritic changes after CRS in either intact or ovariectomized animals, display a CRS-induced increase in spine density in ovariectomized animals but not in intact females with circulating estradiol; yet amygdala-projecting PFC neurons show CRS-induced spine density that is enhanced in intact females, accompanying the dendrite expansion.Citation50 Regarding function, as shown by lesion studies, contralateral prefrontal to amygdala projection is key to the ability of acute foot shock stress to impair eyeblink conditioning in female rats.Citation69

Dopaminergic systems

Estradiol stimulates dopamine release independently of nuclear ERs.Citation74 Moreover, there is a sex difference in the ability of estrogen to promote dopamine release where membrane-associated, nongenomic ERs have been demonstrated in dopamine-terminal areas—including the caudate, PFC, and nucleus accumbens—with effects promoting a place memory as opposed to a response memory bias.Citation75 High-dose estrogen treatment used in the initial contraceptive preparations exacerbated symptoms of Parkinson disease in women.Citation76 However, now, with lower doses of estradiol, there is evidence for neuroprotection in Parkinson disease and the involvement of multiple signaling pathways,Citation77 including the G-protein coupled ER (GPER1).Citation75

Sex differences in cerebellum

The cerebellum is responsive to estrogens, generates both estradiol and progesterone during its development, and in humans is implicated in disorders that show sex differences.Citation78,Citation79 Estrogens direct the growth of dendrites in the developing cerebellum and regulate both excitatory and inhibitory balance, affecting not only motor coordination but also memory and mood regulation.Citation79 The cerebellum is involved in associative learning processes of conditioned anticipatory safety from pain and mediates sex differences in the underlying neural processes.Citation80

Sex differences in pain sensitivity and circuitry

Morphine is less potent in alleviating pain in women than in men.Citation80 Gonadal steroids, primarily through ERα and androgen receptors in the periaqueductal gray, are known to exert a sexually dimorphic regulation of spinal antinociception.Citation81,Citation82 For migraine, a pain condition that is more frequent in women than in men, women have been shown to have increased pain sensitivity.Citation83 Moreover, women with migraine have thicker posterior insula and precuneus cortices than male migraineurs, as well as healthy controls of both sexes.Citation83

Empathy

Assessments of empathy in male and female volunteers, in which both sexes perform equally well on three separate tests, reveal different brain regional patterns of activation as seen by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).Citation84 Thus, in their daily lives, men and women use different “strategies” in their relationships and approaches to solving problems and yet, on average and with considerable overlap, do most tasks equally well.Citation84,Citation85

Neuroprotection

Estradiol protects neurons from excitotoxic damage due to seizures and stroke, as well as in Alzheimer disease.Citation37,Citation86 The exact role in this process of cell nuclear ERs found on inhibitory interneurons is unclear, but one clue is the ability of estrogens to enhance neuropeptide Y (NPY) expression and release, as NPY has antiexcitatory actions.Citation87,Citation88 Additionally, estradiol translocation via ERβ into mitochondria regulates mitochondrial calcium sequestration, including B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) translocation.Citation89

Investigation of the ability of estrogens to protect against stroke damage, as well as Alzheimer and Parkinson disease, has demonstrated that the brain is capable of locally generating estrogens either from androgens or possibly directly from cholesterol.Citation90 Aromatization of androgen precursors produces estrogenic steroids and knock-out of the aromatase enzyme increases ischemic damage even beyond that found after ovariectomy of wild-type mice.Citation86 Moreover, like estrogens, androgens have neuroprotective effects.Citation91 The brain also appears to have the capacity to locally generate the androgen dihydrotestosterone from as yet unknown precursors, independently of the gonads, in an animal model in which mild exercise increases neurogenesis in a manner facilitated by those androgens.Citation92

Estrogen and the aging hippocampus and prefrontal cortex

Estrogen actions have also illuminated the aging process insofar as they have revealed the progressive loss of plasticity and hormone responsiveness, which is not necessarily irreversible.

Hippocampus

In contrast to estrogen modulation of synaptic plasticity in young female rats, estrogen treatment failed to increase synapse density in CA1 of aged ovariectomized rats.Citation37 At the subsynaptic level, whereas estradiol was able to maintain select network properties in the aged hippocampus,Citation37 the loss of structural plasticity in the aged hippocampus was accompanied by half as many synapses containing ERα as in young animals irrespective of estrogen treatment. In addition, though subtle, an estrogen-induced decrease in synaptic ERα levels was observed in both axon terminals and dendritic spines selectively in the young cohort, once again pointing to a loss of responsivity by the neurons in the aged CA1 subfield.Citation93 Moreover, phosphorylated LIMK (pLIMK) located within the CA1 synapses activated by estrogen—which is critically important in regulation of actin dynamics linked to spine formation—showed selective responsivity to estrogen in the young cohort, whereas the aged animals had decreased synaptic pLIMK levels in CA1 that was not reversed by estrogen treatment.Citation94 Age-related losses of responsivity to estrogen with respect to structural plasticity, molecular rearrangement, and biochemical function correlate with an age-related loss of estrogen-induced memory enhancement. In young, but not aged, ovariectomized rats, estrogen rescues the learning deficits associated with experimentally induced cholinergic impairment.Citation37

Prefrontal cortex

The nonhuman primate model has provided the best insights into the aging effects on the PFC, which is important for working memory and self-regulation.Citation37 After ovariectomy, the decrease in spine density in the young monkeys compared with those receiving estradiol-replacement treatment occurred against a background of an adaptive increase in dendritic length in the young vehicle-treated animals, implying that in spite of the higher spine density in the estradiol-treated group, overall there is no difference in the number of spines per neuron in the young cohort. In contrast, there was an estrogen-induced spinogenesis in the aged cohort, which occurred against the background of an age-related reduction in spine density of the aged vehicle- treated group. Thus, the vulnerability to cognitive decline in the aged vehicle-treated group is explained by both an age-induced loss of spines on top of an estrogen deficiency-induced loss of spines.

Because spine size is highly correlated with both synapse size as well as glutamate receptor number,Citation37 it was noteworthy that estrogen shifts the distribution of spine-head diameter toward smaller size in both the young and aged animals, but aging dramatically reduced the representation of spines with small heads and long necks. This age-related selective loss of small spines (and the partial recovery with estrogen) fits in nicely with a developing framework in neurobiology of the essential role that small spines play in learning and memory, with thin spines involved in “learning” and big, mushroom-type spines representing “memory” traces.Citation37 What is therefore most detrimental for the aging animal's cognitive performance is that small, plastic spines are missing in the dorsolateral PFC. When estrogen replacement is provided to the aged animals, their cognitive performance matches the performance of young animals in spite of having an overall smaller spine density than the young estrogen-treated animals. This could indicate that a modest increase in small spines goes a long way in providing neurobiological resilience.

Another finding from the infrahuman primate model is that surgical menopause impairs cognitive function in a manner that is ameliorated by estrogen treatment.Citation95 The presence of abnormal donut-shaped mitochondria that generate excess free radicals was a factor.Citation95,Citation96 Although presynaptic bouton density or size was not significantly different across groups distinguished by age or menses status, cognitive performance accuracy correlated positively with the number of total and straight mitochondria in presynaptic endings of the dorsolateral PFC. In contrast, accuracy correlated inversely with the frequency of boutons containing donut-shaped mitochondria, and those terminals exhibited smaller active zone areas and fewer docked synaptic vesicles than those with straight or curved mitochondria. Estrogen administration ameliorated cognitive performance deficits and reduced the numbers of donut-shaped mitochondria, suggesting that hormone therapy may benefit cognitive aging, in part by promoting mitochondrial and synaptic health in the PFC and possibly in other parts of the brain.Citation95

Conclusion

The origins of sex differences in the brain and behavior depend not only on developmentally programmed secretion of hormones during sensitive periods of early life but also on genes and sex chromosomes, as well as mitochondria from the mother. Moreover, there is continuous interaction between genes and experiences, now referred to as “epigenetics,” which changes the expression of genes over the life course. Knowing that the entire brain is affected by sex hormones with subtle sex differences, we are entering a new era in our ability to understand and appreciate the diversity of genderrelated behaviors and brain functions. This will enhance “personalized medicine” that recognizes sex differences in disorders and their treatment and will improve understanding of how men and women differ, not by ability, but by the “strategies” they use in their daily lives.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- YoungWC.GoyRW.PhoenixCH.Hormones and sexual behavior.Science.1964143360321221814077548

- HarrisGW.Electrical stimulation of the hypothalamus and the mechanism of neural control of the adenohypophysis.J Physiol.1948107441842916991822

- MeitesJ.Short history of neuroendocrinology and the International Society of Neuroendocrinology.Neuroendocrinology.19925611101641067

- SchallyAV.ArimuraA.KastinAJ.Hypothalamic regulatory hormones.Science.1973179713413504345570

- GuilleminR.Peptides in the brain: the new endocrinology of the neuron.Science.19782024366390402212832

- JensenE.GreeneGL.ClossLE.DeSombreER.NadjiM.Receptors reconsidered a 20-year perspective.Recent Prog Harm Res.198238140

- ToftD.GorskiJ.A receptor molecule for estrogens: isolation from the rat uterus and preliminary characterization.Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.1966556157415815227676

- PfaffDW.KeinerM.Atlas of estradiol-concentrating cells in the central nervous system of the female rat.J Comp Neurol.197315121211584744471

- StumpfWE.SarM.Steroid hormone target sites in the brain: the differential distribution of estrogen, progestin, androgen and glucocorticosteroid.J Steroid Biochem.1976711-12116311701025363

- YoungW.The Hormones and Mating Behavior. In: Young W, ed.Sex and Internal Secretions. 7th ed. Baltimore.MD: Williams and Wilkins 196111731239

- McEwenBS.AlvesSH.Estrogen actions in the central nervous system.Endocr Rev.199920327930710368772

- McEwenBS.DeKloetER.RosteneW.Adrenal steroid receptors and actions in the nervous system.Physiol Rev.1986664112111883532143

- LoyR.GerlachJ.McEwenBS.Autoradiographic localization of estradiol-binding neurons in rat hippocampal formation and entorhinal cortex.Brain Res.198846722452513378173

- McEwenBS.MilnerTA.Hippocampal formation: shedding light on the influence of sex and stress on the brain.Brain Res Rev.200755234335517395265

- KellyMJ.LevinER.Rapid actions of plasma membrane estrogen receptors.Trends Endocrinol Metab.200112415215611295570

- BlissTV.LomoT.Long-lasting potentiation of synaptic transmission in the dentate area of the anaesthetized rabbit following stimulation of the perforant path.J Physiology.19732322331356

- ParnavelasJ.LynchG.BrechaN.CotmanC.GlobusA.Spine loss and regrowth in hippocampus following deafferentation.Nature.1974248544371734818565

- BennettE.DiamondM.KrechD.RosenzweigM.Chemical and anatomical plasticity of brain.Science.1964146364461061914191699

- GreenoughWT.VolkmarFR.Pattern of dendritic branching in occipital cortex of rats reared in complex environments.Exp Neurol.19734024915044730268

- ArnoldA.BreedloveS.Organizational and activational effects of sex steroids on brain and behavior: a reanalysis.Horm Behav19851944694983910535

- DeVoogdT.NottebohmF.Gonadal hormones induce dendritic growth in the adult avian brain.Science.198121445172022047280692

- NottebohmF.Why are some neurons replaced in adult brain?J Neurosci.200222362462811826090

- AltmanJ.DasGD.Autoradiographic and histological evidence of postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis in rats.J Comp Neurol.196512433193365861717

- KaplanMS.BellDH.Neuronal proliferation in the 9-month-old rodent-radioautographic study of granule cells in the hippocampus.Exp Brain Res.1983521156628589

- CameronHA.GouldE.Adult neurogenesis is regulated by adrenal steroids in the dentate gyrus.Neuroscience.19946122032097969902

- KaplanMS.Environment complexity stimulates visual cortex neurogenesis: death of a dogma and a research career.Trends Neurosci.2001241061762011576677

- SpaldingKL.BergmannO.AlkassK.et alDynamics of hippocampal neurogenesis in adult humans.Cell.201315361219122723746839

- NakamuraNH.AkamaKT.YuenGS.McEwenBS.Thinking outside the pyramidal cell: unexplored contributions of interneurons and neuropeptide Y to estrogen-induced synapse formation in the hippocampus.Rev Neurosci.200718111317405448

- TerasawaE.TimirasP.Electrical activity during the estrous cycle of the rat: cyclic changes in limbic structures.Endocrinology.19688322072164874282

- SherwinBB.Estrogen and/or androgen replacement therapy and cognitive functioning in surgically menopausal women.Psychoneuroendocrinology19881343453573067252

- WoolleyC.GouldE.FrankfurtM.McEwenBS.Naturally occurring fluctuation in dendritic spine density on adult hippocampal pyramidal neurons.J Neurosci.19901012403540392269895

- McEwenBS.AkamaKT.Spencer-SegalJL.MilnerTA.WatersEM.Estrogen effects on the brain: actions beyond the hypothalamus via novel mechanisms.Behav Neurosci.2012126141622289042

- TaboriNE.StewartLS.ZnamenskyV.et alUltrastructural evidence that androgen receptors are located at extranuclear sites in the rat hippocampal formation.Neuroscience.2005130115116315561432

- RomeoRD.StaubD.JasnowAM.KaratsoreosIN.ThorntonJE.McEwenBS.Dihydrotestosterone increases hippocampal N-methyl-D-aspartate binding but does not affect choline acetyltransferase cell number in the forebrain or choline transporter levels in the CA1 region of adult male rats.Endocrinology.200514642091209715661864

- ChristensenA.DewingP.MicevychP.Membrane-initiated estradiol signaling induces spinogenesis required for female sexual receptivity.J Neurosci.20113148175831758922131419

- McEwenBS.GrayJD.Nasca C 60 years of neuroendocrinology: redefining neuroendocrinology: stress, sex and cognitive and emotional regulation.J Endocrinol.20152262T67T8325934706

- HaraY.WatersEM.McEwenBS.MorrisonJH.Estrogen Effects on cognitive and synaptic health over the lifecourse.Physiol Rev.201595378580726109339

- HaoJ.RappPR.JanssenWG.et alInteractive effects of age and estrogen on cognition and pyramidal neurons in monkey prefrontal cortex.Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.2007104271146511470 17592140

- ChenJR.YanYT.WangTJ.ChenLJ.WangYJ.TsengGF.Gonadal hormones modulate the dendritic spine densities of primary cortical pyramidal neurons in adult female rat.Cerebral Cortex.200919112719272719293395

- McCarthyMM.ArnoldAP.Reframing sexual differentiation of the brain.Nat Neurosci.201114667768321613996

- GorskiRA.GordonJH.ShryneJE.SouthamAM.Evidence for a morphological sex difference within the medial preoptic area of the rat brain.Brain Res.19781482333346656937

- WitelsonSF.GlezerII.KigarDL.Women have greater density of neurons in posterior temporal cortex.J Neurosci.199515 pt 134183428

- McEwenB.MilnerTA.Understanding the broad influence of sex hormones and sex differences in the brainJ Neurosci Res.2017951-22439.doi:10.1002/jnr.23809.27870427

- ForgerNG.Epigenetic mechanisms in sexual differentiation of the brain and behaviour.Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci.201637116882015011426833835

- EilandL.RamroopJ.HillMN.ManleyJ.McEwenBS.Chronic juvenile stress produces corticolimbic dendritic architectural remodeling and modulates emotional behavior in male and female rats.Psychoneuroendocrinology.2012371394721658845

- ParschJ.EllegrenH.The evolutionary causes and consequences of sex-biased gene expression.Nat Rev Genet.2013142838723329110

- LeunerB.Mendolia-loffredoS.ShorsTJ.Males and females respond differently to controllability and antidepressant treatment.Biol Psychiatry.2004561296497015601607

- GaleaLA.WainwrightSR.RoesMM.Duarte-GutermanP.ChowC.HamsonDK.Sex, hormones and neurogenesis in the hippocampus: hormonal modulation of neurogenesis and potential functional implications.J Neuroendocrinol.201325111039106123822747

- BangasserDA.CurtisA.ReyesBA.et alSex differences in corticotropin-releasing factor receptor signaling and trafficking: potential role in female vulnerability to stress-related psychopathology.Mol Psychiatry.2010159877:89690420548297

- ShanskyRM.HamoC.HofPR.LouW.McEwenBS.MorrisonJH.Estrogen promotes stress sensitivity in a prefrontal cortex-amygdala pathway.Cereb Cortex.201020112560256720139149

- McCarthyMM.Multifaceted origins of sex differences in the brain.Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci.201637116882015010626833829

- BabbJA.MasiniCV.DayHE.CampeauS.Stressor-specific effects of sex on HPA axis hormones and activation of stress-related neurocircuitry.Stress.201316666467723992519

- BohacekJ.ManuellaF.RoszkowskiM.MansuyIM.Hippocampal gene expression induced by cold swim stress depends on sex and handling.Psychoneuroendocrinology20155211225459888

- NugentBM.WrightCL.ShettyAC.et alBrain feminization requires active repression of masculinization via DNA methylation.Nat Neurosci.201518569069725821913

- McCarthyMM.ArnoldAP.BallGF.BlausteinJD.De VriesGJ.Sex differences in the brain: the not so inconvenient truth.J Neurosci.20123272241224722396398

- DumanRS.MonteggiaLM.A neurotrophic model for stress-related mood disorders.Biol Psychiatry.200659121116112716631126

- MagarinosAM.LiCJ.Gal TothJ.et alEffect of brain-derived neurotrophic factor haploinsufficiency on stress-induced remodeling of hippocampal neurons.Hippocampus.201121325326420095008

- BathKG.SchilitA.LeeFS.Stress effects on BDNF expression: effects of age, sex, and form of stress.Neuroscience.201323914915623402850

- SenS.DumanR.SanacoraG.Serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor, depression, and antidepressant medications: meta-analyses and implications.Biol Psychiatry.200864652753218571629

- NotarasM.HillR.van den BuuseM.The BDNF gene Val66Met polymorphism as a modifier of psychiatric disorder susceptibility: progress and controversy.Mol Psychiatry.201520891693025824305

- ShiL.ZhangZ.SuB.Sex biased gene expression profiling of human brains at major developmental stages.Sci Rep.201662118126880485

- DuclotF.KabbajM.The estrous cycle surpasses sex differences in regulating the transcriptome in the rat medial prefrontal cortex and reveals an underlying role of early growth response 1.Genome Biol.20151625626628058

- HodesGE.PfauML.PurushothamanI.et alSex differences in nucleus accumbens transcriptome profiles associated with susceptibility versus resilience to subchronic variable stress.J Neurosci.20153550163621637626674863

- HeimanM.SchaeferA.GongS.et alA translational profiling approach for the molecular characterization of CNS cell types.Cell.2008135473874819013281

- GaleaLA.McEwenBS.TanapatP.DeakT.SpencerRL.DhabharFS.Sex differences in dendritic atrophy of CA3 pyramidal neurons in response to chronic restraint stress.Neuroscience.19978136896979316021

- BowmanRE.BeckKD.LuineVN.Chronic stress effects on memory: sex differences in performance and monoaminergic activity.Horm Behav.2003431485912614634

- WoodGE.ShorsTJ.Stress facilitates classical conditioning in males, but impairs classical conditioning in females through activational effects of ovarian hormones.Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.1998957406640719520494

- ShorsTJ.ChuaC.FaldutoJ.Sex differences and opposite effects of stress on dendritic spine density in the male versus female hippocampus.J Neurosci.200121166292629711487652

- ShorsTJ.A trip down memory lane about sex differences in the brain.Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci.201637116882015012426833842

- BeckerJB.MonteggiaLM.Perrot-SinalTS.et alStress and disease: is being female a predisposing factor?J Neurosci.20072744118511185517978023

- MilnerTA.BursteinSR.MarroneGF.et alStress differentially alters mu opioid receptor density and trafficking in parvalbumin-containing interneurons in the female and male rat hippocampus.Synapse.2013671175777223720407

- LuineVN.BeckKD.BowmanRE.FrankfurtM.MacLuskyNJ.Chronic stress and neural function: accounting for sex and age.J Neuroendocrinol.2007191074375117850456

- McEwenBS.MorrisonJH.The brain on stress: vulnerability and plasticity of the prefrontal cortex over the life course.Neuron.2013791162923849196

- MermelsteinPG.BeckerJB.SurmeierDJ.Estradiol reduces calcium currents in rat neostriatal neurons via a membrane receptor.J Neurosci.19961625956048551343

- AlmeyA.MilnerTA.BrakeWG.Estrogen receptors in the central nervous system and their implication for dopamine-dependent cognition in females.Horm Behav.20157412513826122294

- BedardPJ.LangelierP.VilleneuveA.Oestrogens and the extrapyramidal system.Lancet.197728052-805313671368

- BourqueM.DluzenDE.Di PaoloT.Signaling pathways mediating the neuroprotective effects of sex steroids and SERMs in Parkinson's disease.Front Neuroendocrinol.201233216917822387674

- DeanSL.McCarthyMM.Steroids, sex and the cerebellar cortex: implications for human disease.Cerebellum.200871384718418672

- HedgesVL.EbnerTJ.MeiselRL.MermelsteinPG.The cerebellum as a target for estrogen action.Front Neuroendocrinol.201233440341122975197

- LabrenzF.IcenhourA.ThurlingM.et alSex differences in cerebellar mechanisms involved in pain-related safety learning.Neurobiol Learn Mem.2015123929926004678

- LoydDR.MurphyAZ.The neuroanatomy of sexual dimorphism in opioid analgesia.Exp Neurol.2014259576324731947

- MogilJS.Sex differences in pain and pain inhibition: multiple explanations of a controversial phenomenon.Nat Rev Neurosci.2012131285986623165262

- MalekiN.LinnmanC.BrawnJ.BursteinR.BecerraL.BorsookD.Her versus his migraine: multiple sex differences in brain function and structure.Brain.2012135 pt 82546255922843414

- DerntlB.FinkelmeyerA.EickhoffS.et alMultidimensional assessment of empathic abilities: neural correlates and gender differences.Psychoneuroendocrinology.2010351678219914001

- McEwenBS.LasleyEN.The End Of Sex As We Know It. Cerebrum: The Dana Forum on Brain Science; vol 7. Washington, DC: Dana Press.2005

- McCulloughLD.BlizzardK.SimpsonER.OzOK.HumPD.Aromatase cytochrome P450 and extragonadal estrogen play a role in ischemic neuroprotection.J Neurosci.200323258701870514507969

- NakamuraNH.ResellDR.AkamaKT.McEwenBS.Estrogen and ovariectomy regulate mRNA and protein of glutamic acid decarboxylases and cation-chloride cotransporters in the adult rat hippocampus.Neuroendocrinology.200480530832315677881

- LedouxVA.SmejkalovaT.MayRM.CookeBM.WoolleyCS.Estradiol facilitates the release of neuropeptide Y to suppress hippocampus-dependent seizures.J Neurosci.20092951457146819193892

- NilsenJ.BrintonRD.Mitochondria as therapeutic targets of estrogen action in the central nervous system.Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord.20043429731315379606

- HojoY.HattoriTA.EnamiT.et alAdult male rat hippocampus synthesizes estradiol from pregnenolone by cytochromes P45017α and P450 aromatase localized in neurons.Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.2004101386587014694190

- PikeCJ.NguyenTV.RamsdenM.YaoM.MurphyMP.RosarioER.Androgen cell signaling pathways involved in neuroprotective actions.Horm Behav.200853569370518222446

- OkamotoM.HojoY.InoueK.et alMild exercise increases dihydrotestosterone in hippocampus providing evidence for androgenic mediation of neurogenesis.Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.201210932131001310522807478

- AdamsMM.FinkSE.ShahRA.et alEstrogen and aging affect the subcellular distribution of estrogen receptor-α in the hippocampus of female rats.J Neurosci.20022293608361411978836

- YildirimM.JanssenWG.TaboriNE.et alEstrogen and aging affect synaptic distribution of phosphorylated LIM kinase (pLIMK) in CA1 region of female rat hippocampus.Neuroscience.2008152236037018294775

- HaraY.YukF.PuriR.JanssenWG.RappPR.MorrisonJH.Presynaptic mitochondrial morphology in monkey prefrontal cortex correlates with working memory and is improved with estrogen treatment.Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.2014111148649124297907

- PicardM.McEwenBS.Mitochondria impact brain function and cognitionProc Natl Acad Sci U S A.201411117824367081