Abstract

The main goal of this review is to consider the main forms of dysfunctional neurocognition seen in individuals with clinically significant psychopathic traits (ie, reduced guilt/empathy and increased impulsive/antisocial behavior). A secondary goal is to examine the extent to which these forms of dysfunction are seen in both adults with psychopathic traits and adolescents with clinically significant antisocial behavior that may also involve callous-unemotional traits (reduced guilt/empathy). The two main forms of neurocognition considered are emotional responding (to distress/pain cues and emotional stimuli more generally) and reward-related processing. Highly related forms of neurocognition, the response to drug cues and moral judgments, are also discussed. It is concluded that dysfunction in emotional responsiveness and moral judgments confers risk for aggression across adolescence and into adulthood. However, reduced reward-related processing, including to drug cues, is only consistently found in adolescents with clinically significant antisocial behavior, not adults with psychopathy.

El objetivo central de este artículo es considerar las principales formas de disfunción neurocognitiva que se observan en sujetos con rasgos psicopáticos clínicamente significativos (por ejemplo, disminución de la empatía / culpa y aumento del comportamiento impulsivo / antisocial). En segundo lugar, se analiza en qué medida aparecen estas formas de disfunción tanto en adultos con rasgos psicopáticos como en adolescentes con un comportamiento antisocial clínicamente significativo que también puede implicar características insensibles / frías (disminución de la empatía / culpa). Las dos formas principales de neurocognición examinadas son la reactividad emocional (a los signos de angustia y dolor, y los estímulos emocionales en general) y el sistema de recompensa. También se discuten formas muy relacionadas de la neurocognición, como son la respuesta a estímulos de drogas y los juicios morales. En conclusión, la aparición de una disfunción en la reactividad emocional y los juicios morales confiere un riesgo de agresión durante la adolescencia y la edad adulta. Sin embargo, en adolescentes con comportamiento antisocial clínicamente significativo se encuentra de manera consistente una reducción del procesamiento relacionado con la recompensa, incluyendo la respuesta a drogas ; lo que no aparece en adultos con psicopatía.

Cet article a pour principal objectif d’envisager les principales formes de dysfonction neurocognitive observées chez des sujets présentant des traits psychopathiques cliniquement significatifs (par exemple, empathie/culpabilité réduite et comportement impulsif/antisocial majoré). Secondairement, il sera analysé dans quelle mesure ces formes de dysfonction sont observées à la fois chez des adultes ayant des traits psychopathiques et chez des adolescents ayant un comportement antisocial cliniquement significatif qui peut aussi impliquer des traits insensibles/froids (empathie/culpabilité réduite). Les deux principales formes de neurocognition examinées sont la réactivité émotionnelle (aux signes de détresse et de douleur et aux stimuli émotionnels plus généralement) et le système de récompense. Des formes de neurocognition très reliées, la réponse aux stimuli des drogues et aux jugements moraux, sont aussi discutées. En conclusion, une dysfonction observée dans la réactivité émotionnelle et les jugements moraux confère un risque pour l’agression au cours de l’adolescence et à l’âge adulte. Néanmoins, une diminution du système de récompense, y compris les stimuli des drogues, est régulièrement observée chez des adolescents au comportement antisocial cliniquement significatif et pas chez les adultes psychopathes.

Introduction

The term psychopathy characterizes an increased risk for antisocial behavior coupled with pronounced emotional deficits reflecting reduced guilt, remorse, and empathy. Citation1 , Citation2 In children this emotional component is typically referred to as callous-unemotional (CU) traits. Citation1 Children and youth with CU traits are at notably increased risk for meeting criteria for psychopathy as adults. Citation3 Psychopathic traits are a source of considerable concern as they are associated with particularly heightened levels of aggression that may be less amenable to treatment than other factors increasing the risk for violence. Citation1 , Citation2 The goal of this review is to consider the main neurocognitive impairments seen in individuals with clinically significant psychopathic traits. Given the necessity for brevity, several sections of the literature will not be considered: First, there will be no consideration of data from healthy participants who vary in levels of psychopathic traits. While it is useful to know the extent to which a form of pathology associated with specific symptoms is seen in healthy individuals, it is probably unwise to assume that data from healthy individuals is informative for understanding individuals with a clinically significant condition. The clearest example of the necessity for caution is provided by the literature relating reward responsiveness to impulsiveness (a core symptom of Attention Deficit-Hyperactivity Disorder [ADHD]). In a critical meta-analytic review of the literature, Citation4 the authors concluded that, while increased striatal responsiveness to reward was associated with increased impulsiveness in healthy individuals, it was associated with decreased impulsiveness in patients with ADHD. Given the evidence presented by this review, it would be unwise to make claims regarding the functional impairment underpinning clinical ADHD, and potentially other conditions like psychopathic traits, on the basis of data obtained from healthy individuals.

Second, neither data from structural imaging nor resting-state studies will be considered. Reviews of this literature are available elsewhere. The data are clearly informative regarding the pathophysiology of the disorder. However, the focus on this paper is on neurocognition. Any functional interpretation of structural imaging or resting state data is inevitably reverse inferencing – not based on an experimental manipulation of a functional process.

This review will consider the data from studies with both children and adults. Indeed, this review will address the extent to which the literature is consistent across adolescent and adult populations. However, it is necessary to note some concern here. The functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) literature with adolescent samples has typically considered youth with DSM diagnoses of Conduct Disorder (CD) or Oppositional Defiant Disorders, relative to comparison youth, Citation5 , Citation6 and then sometimes examined the modulation of blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) responses by psychopathic or callous/unemotional traits. Citation7 , Citation8 In contrast, the literature with adults has typically ignored psychiatric diagnostic status (including that of the adult homologue of CD, antisocial personality disorder) in favor of examining forensic populations either differing by group according to their Psychopathy Checklist Revised (PCL-R) score Citation9 , Citation10 or via examination of severity of functional impairments as a function of level of psychopathic traits as indexed by the Hare Psychopathy Checklist, Revised (PCL-R). Citation11 , Citation12 As such, this review might be better conceptualized as addressing the extent to which specific impairments in neurocognition are associated with clinically significant levels of antisocial behavior/psychopathic traits. Of course, this type of focus is more compatible with the more recent push to generally consider psychiatry in terms of forms of pathology giving rise to symptom groups rather than considering the pathology found in individuals showing specific clusters of behavioral symptoms. Citation13

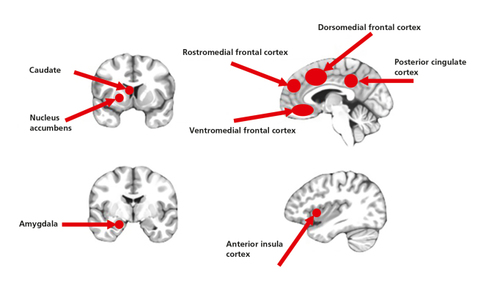

The review will concentrate on two related main foci of the fMRI literature on clinically significant psychiatric traits, emotional and reward processing, and implications of these functions for responding to drug cues and moral judgements. Emotional/reward processing implicates a series of highly interconnected regions including the amygdala, striatum, anterior insula, anterior cingulate/dorsomedial, rostromedial, ventromedial frontal and posterior cingulate cortices (Figure 1) . These regions in turn have a web of connections with other brain areas. The amygdala and striatum are particularly important for forms of reinforcement-based learning. Anterior insula and dorsomedial frontal cortices are particularly important for selecting responses/avoiding/inhibiting responses as a function of expected value information and other cues. Rostromedial, ventromedial frontal, and posterior cingulate cortices are particularly important for representing the value (and possibly with respect to rostromedial frontal cortex, in particular, maintaining the value) of response choices.

Attention-based views, dominant in the 1980s and 1990s, and still very prominent today, Citation14 will receive less attention but will be briefly considered.

Emotional processing

Emotional facial expressions

Emotional expressions have a communicative function: they both modulate ongoing behavior and allow the rapid transmission of valence information regarding objects and actions. Citation15 This is seen, for example, in social referencing where the observer learns the value of a stimulus based on another individual’s emotional reaction to it (eg, the negative value of a novel threat because the caregiver shows fear towards it). There has been a considerable amount of work that has investigated the processing of emotional facial expressions in adolescent and adult populations with psychopathic traits. This is related to suggestions that psychopathic traits might particularly relate to a reduced response to the distress of others. Citation15 According to this view, such a reduced response should be associated with reduced learning to avoid actions that harm other individuals (the individual finds the “punishment” of the other individual’s distress less aversive) and thus reduced avoidance of the commission of actions that might harm other individuals. Citation15

Face stimuli are processed by a series of neural regions including those related to emotional processing listed above as well as temporal cortical regions (eg, fusiform and superior temporal cortex) that are particularly involved in processing faces relative to inanimate objects. Citation16 Many of these regions (eg, the amygdala, anterior insula, and fusiform cortex) show stronger responses to emotional relative to neutral faces. Citation16 Moreover, there are indications of regional specification regarding particular emotional expressions; the amygdala appears particularly responsive to fearful, sad, and happy expressions but not angry and disgusted expressions, while anterior insula cortex is particularly responsive to disgust and anger expressions. Citation16

Youth and adults with conduct problems, particularly those with psychopathic or CU traits, have been reported to show deficits in expression recognition, perhaps particularly for fearful, sad, and happy expressions, though this is debated. Citation17 , Citation18 The impaired recognition of fearfulness and sadness is pervasive, applying also to vocal tones and body postures.

Youth with conduct problems, particularly when marked with psychopathic or CU traits, consistently show reduced responses to facial expression stimuli (particularly fearful and sad expressions) in emotion/face processing regions, including the amygdala. Citation5 , Citation7 , Citation19 - Citation22 In a particularly interesting study, and consistent with theory, Citation15 Lozier and colleagues revealed that the positive relationship between CU traits and aggression was mediated by the reduced responsiveness of the amygdala to the distress of other individuals. Citation20 Work with adults with psychopathy also reports similarly reduced BOLD responses in affect/face processing regions to facial expressions relative to comparison adults. Citation9 , Citation11 , Citation23 However, only one of these studies specifically reported reduced amygdala responses. Citation23

In summary, the existing literature relatively reliably indicates reduced responsiveness to facial expressions, particularly distress cues, in children and adults with conduct problems that may be particularly marked in those with psychopathic traits. The regions implicated across studies are not always consistent–and the reduced amygdala responsiveness is seen much more in the work with adolescents than that with adults–but the basic finding of reduced neural responsiveness appears robust.

Pain stimuli

The facial expressions of another individual in pain can also be considered a distress cue. However, many studies examining responsiveness to the pain of another individual in individuals with psychopathic/CU traits have often used visual stimuli depicting painful events (a hand caught in a slamming door) rather than facial expressions of pain. These are depictions of events associated with another individual’s pain, and require either interpretation or some association with the aversiveness of such events in the viewer’s past.

A series of studies have identified a “pain matrix”; a network of brain regions that respond to the sight of another individual in pain. These regions include the neural regions related to emotional processing listed above as well as supplementary motor area (for a meta-analytic review of this literature, see ref 24). The activation of the supplementary motor area is interesting as it probably reflects activity relating to the association of the visual image with comparable events in the observer’s past.

It has been known for some time that individuals with psychopathy show reduced emotional (autonomic) responses to the sight of other individuals in apparent pain. Citation25 Recent fMRI studies have examined the neural basis of this dysfunction in youth with conduct problems. Citation26 - Citation28 These studies have reported that observing others in pain was associated with reduced activity within rostral medial/anterior cingulate cortex, the amygdala and insula cortex in this population. Citation26 - Citation29 Work with adults with psychopathy has revealed that all of these regions are also associated with reduced responsiveness in this population as a function of level of psychopathy. Citation10 , Citation12 , Citation30 For two of the studies (one child, one adult), asking the participants to imagine the events were happening to another were particularly associated with reduced activity as a function of psychopathic traits. Citation12 , Citation26 However, it should be noted that a third study found psychopathy effects only when participants were not asked to “feel with the receiving (50%) or the approaching (50%) hand” (they were present under passive viewing conditions). Citation10

In summary, the existing literature relatively reliably indicates reduced responsiveness to pain stimuli in children and adults with conduct problems, particularly as a function of psychopathic traits. Studies have relatively reliably identified reduced responding within dorsomedial and anterior insula cortices and, though less often, the amygdala.

Emotional stimuli generally and the role of attention

In addition to the above evidence of reduced responding to emotional expressions and pain stimuli, there is some work indicating that responding during aversive conditioning and to emotional stimuli may be generally compromised in youth with callous and unemotional traits and adults with psychopathy. With respect to aversive conditioning, behavioral work has indicated that this is reduced in adults with psychopathy relative to comparison adults (ie, reduced differentiation in autonomic responding between the stimulus associated with the punishment and the one not associated with the punishment) Citation31 though findings in adolescents have been rather more mixed. Citation32 , Citation33 fMRI work has indicated that CU traits in youth and psychopathy in adults are associated with reduced amygdala and anterior cingulate responding. Citation33 , Citation34 With respect to emotional responding, work has indicated that both youth with CU traits Citation35 and adults with psychopathic traits Citation36 , Citation37 show reduced responses to negative pictures within the amygdala, ventromedial frontal cortex, and other emotion-associated regions relative to comparison individuals.

The latter two studies Citation36 , Citation37 together with other work Citation10 , Citation12 , Citation26 are interesting because they indicate that attentional manipulations can, under certain circumstances, influence the extent to which individuals with psychopathic traits show reduced neural responses to emotional stimuli. Most of the studies reviewed above, indicating reduced responsiveness, have used passive viewing conditions, or conditions where the participant is engaged in a low attentional load task such as gender identification. However, two studies revealed that any reduced responding to emotional images in adults with psychopathy was effectively “normalized” when the participants were explicitly asked to attend to the emotional content of the picture and classify the picture as emotional or nonemotional Citation37 or enhance their emotional responding. Citation36 A third study reported that this also occurred if participants were encouraged to “empathize” with the actors in a video. Citation10 However, it should be noted that two further studies reported, in contrast, that the association with psychopathy and reduced responding to pain stimuli was most marked during the empathy for others condition. Citation12 , Citation26

These findings are of interest given views that psychopathy might reflect a problem in attention rather than emotion. Citation14 The attention-based views effectively suggest that individuals with psychopathy attend to other features of the stimulus array than the emotional ones and thus show weaker responses to the emotional stimuli. Clearly, such a view is compatible with several of the above findings Citation10 , Citation36 , Citation37 though inconsistent with others. Citation12 , Citation26 Of course, an alternative speculation is that individuals with psychopathy do show reduced responding to emotional stimuli. However, if the intensity of this stimulus is sufficiently heightened, via an attentional manipulation that increases the emotional stimulus’ representational strength, group differences are reduced (because the individuals with lower psychopathic traits reach an asymptote level in responding). This latter view is also compatible with the absence of findings, indicating that individuals with higher psychopathic traits show heightened recruitment of regions implicated in top-down attention during passive viewing and other task manipulations.

Reward responsiveness

The second main focus of the fMRI literature on clinically significant psychiatric traits considered here is on reward responsiveness. There is a considerable animal and human literature on regions involved in responding to reward. An adequate review of this literature is beyond the scope of the current paper (see instead ref 38). However, the regions typically implicated are those previously considered with respect to emotional processing; eg, the amygdala, striatum, anterior insula, anterior cingulate/dorsomedial, rostromedial, ventromedial frontal, and posterior cingulate cortices (Figure 1) .

Two possibilities might be considered with respect to the impact of reward on antisocial behavior: First, excessive reward responses to objects in the immediate environment might increase impulsive behavior towards these objects, including aggression; or Second, reduced reward sensitivity/responsiveness, particularly within regions critical for the representation of long-term goals, should result in an individual who makes poorer decisions (response choices will be less well guided by goal-modifiable reward expectations). Such an individual is also more likely to be impulsive and more likely to become frustrated and aggressive as a function of their frustration. Citation39

Very little work supports the suggestion of increased reward responsiveness in adolescents with conduct problems/CU traits. One study reported increased striatal responsiveness to reward in a small sample of youth with externalizing difficulties relative to comparison youth Citation40 while a second found that within a group of adolescents with conduct problems, increasing CU traits were associated with increased striatal responses to watching another win reward–though CU traits did not relate to reward responding when the participant won a reward (ie, there were no indications of heightened responsiveness for reward for the self Citation41 ). In contrast, a series of studies have reported that youth with conduct problems, some of whom also had elevated psychopathic traits, show reduced neural responsiveness to reward/reward omissions within striatum and ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Citation42 - Citation46 However, most of this literature has not indicated a relationship between reward responsiveness and CU/psychopathic traits in particular. The only exception to this is a report of an inverse relationship between rostro- and ventromedial responses during reward anticipation and level of CU traits in a large adolescent sample. Citation47

The literature with adults is less clearcut. Three studies have reported that psychopathy, or antisocial personality disorder, Citation48 were associated with increased reward responsiveness. Citation48 - Citation50 These studies reported that: (i) psychopathy was associated with stronger subjective value-related activity within the nucleus accumbens during inter-temporal choice Citation49 ; (ii) individuals with antisocial personality disorder show increased responses in right orbitofrontal and subgenual cingulate cortices to the receipt of reward Citation48 ; and (iii) individuals with psychopathy show increased nucleus accumbens responses during reward anticipation. Citation50 However, it is notable that this last result held only if the individuals with psychopathy were compared against healthy participants who scored below the healthy participant sample median for impulsivity on a personality measure. There were no group differences between those with psychopathy and healthy participants who scored above the healthy participant median for impulsiveness. Two further studies reported no group differences in reward responsiveness. Citation51 , Citation52 Pujara and colleagues found no significant relationship between psychopathy and nucleus accumbens response to reward relative to neutral reinforcement. Citation51 However, they showed a significant inverse relationship between psychopathy and loss relative to neutral reinforcement. Gregory and colleagues, Citation52 similar to an earlier study with youth with psychopathic tendencies using the same reversal learning task, Citation53 observed a failure in adults with psychopathy to suppress responding within posterior cingulate and insula cortex to unexpected punishment. Finally, an additional study reported diminished responding within rostral anterior cingulate cortex during high, relative to low uncertainty, choice conditions in a decision-making task. Citation54

In summary, the literature relatively clearly indicates that adolescents with conduct problems show reduced reward responsiveness, though whether this relates to severity of CU traits is less certain. Currently, the literature with respect to adults with psychopathy is currently equivocal.

Drug cues

One further way to examine the relationship between reward responsiveness and psychopathy is by examining the relationship between psychopathy and neural responsiveness to drug cues. Substance abuse is associated with a heightened response to drug reward cues and a diminished response to non-drug rewards within regions including dorsomedial frontal, anterior cingulate and anterior insula cortices, the amygdala and striatum (for a review of this literature, see ref 55). This is thought to reflect a learning-based adaptation to the very high levels of dopamine released when the substance is abused such that cues anticipating this release become highly rewarding. Other rewards are associated with relatively weaker dopamine responses and thus become less rewarding. Citation55

If psychopathy is associated with heightened reward responsiveness, one might predict that this learning would occur more rapidly and underlie the emergence of the substance abuse disorders which are often comorbid in this population. Citation56 Individuals with psychopathy should show heightened responsiveness to drug cues. Alternatively, if psychopathy is associated with reduced reward responsiveness, one might predict that individuals with psychopathy should show reduced responsiveness to drug cues. The high comorbidity of psychopathic traits with substance abuse disorders would reflect dysfunction in systems representing anticipated rewards and punishments associated with their decision-making impairments. Citation39

Currently, only three studies have examined this issue. Two, one in an adult Citation57 and the other in an adolescent Citation58 sample, are clearly consistent with the second position. Both studies reported a negative correlation between psychopathic traits and neural response to drug versus neutral images within anterior cingulate cortex, amygdala, and striatum. Citation57 , Citation58 The results of the third study were somewhat more complex. Citation56 In contrast to the previous two studies, this study reported that psychopathic traits were positively correlated with responsiveness to drug relative to food cues within the right anterior insula cortex and the left amygdala. However, only individuals with lower psychopathic traits showed an increasing differentiation in their response to drug vs food cues as a function of duration of drug use. This was seen within left dorsomedial prefrontal and right anterior insula cortex and striatum. Instead, individuals with higher psychopathic traits showed a decreasing differentiation in their drug vs food cues response within these regions. In short, this third study indicated a heightened differentiation in individuals with psychopathy in response to drug versus food cues within the right anterior insula cortex and the left amygdala but that this differentiation was decreased as a function of length of substance abuse within left dorsomedial prefrontal and right anterior insula cortex and striatum as a function of psychopathy level.

In summary, the literature on responsiveness to drug cues has not clarified the situation with respect to reward responsiveness and psychopathy in adults. The Vincent et al study Citation58 is consistent with the previous work with adolescent samples indicating reduced reward responsiveness as a function of conduct disorder/psychopathic traits. Citation42 - Citation46 The results with adults are again relatively inconsistent. Citation56 , Citation57

Moral judgments

Moral judgments involve both emotional responses to the emotional content of the moral/immoral action and decision-making on the basis of this content. Youth with conduct problems and CU traits and adults with psychopathy are compromised in at least some forms of moral judgments (for a more detailed review of the behavioral literature, see ref 59). While they typically show no difficulty in recognizing which acts are transgressions, Citation60 , Citation61 they: (i) distinguish less in their permissibility judgments between acts that harm others relative to those that simply cause social disorder in the absence of rules Citation60 ; (ii) endorse less such harm-based norms though their endorsement of social-disorder based rules remains intact Citation62 ; and (iii) are more likely to allow actions that indirectly harm another. Citation63

Moral judgments involve the recruitment of the regions depicted in Figure 1 (for a meta-analytic review of the moral judgment/fMRI literature, see ref 64). Consistent with the behavioral findings, the fMRI literature has relatively consistently documented in studies using a variety of paradigms that youth and adults with CU/ psychopathic traits show reduced responding within these regions during moral judgment tasks relative to comparison individuals. Citation8 , Citation65 - Citation67

Conclusions

The two main goals of this review were to examine the main neurocognitive impairments seen in individuals with clinically significant psychopathic traits and the extent to which they were seen in adolescent and adult samples. Of course, the immediate concern, particularly with this second aim, is the potential differences in the populations identified in the research on adolescents relative to the research on adults. As noted above, the adolescent literature typically starts with the DSM diagnosis of conduct disorder and then may examine the influence of CU traits. The adult literature typically starts with the psychopathy checklist and may, on the basis of this, examine relationships with particular psychopathic factors (ie, the emotional factor 1 and the more antisocial/impulsive behavior factor 2). Importantly, though, despite these concerns it should by now be clear that the adolescent and adult literature, at least with respect to emotional responding, are consistent with one another. A population, seen in adolescents and adults, marked by high levels of aggression and disrupted empathy/guilt are associated with weaker responding to facial distress cues, indications of pain (perhaps particularly when these are represented as occurring to another individual) and emotional stimuli in the regions depicted in Figure 1 . Moreover, a putative functional process thought to be reliant on this emotional processing, particularly appropriate responding to the distress others, moral judgment is disrupted in this population. This form of reasoning impairment likely increases the risk that these individuals will engage in antisocial behavior that harms other individuals.

There is inconsistency though with respect to the literature on reward processing. The studies with adolescents indicate that a population marked by high levels of aggression is associated with reduced reward responsiveness and that this is echoed in a relatively reduced responsiveness to drug cues. In contrast, the adult literature is relatively evenly divided between studies reporting hyper- and hypo-reward responsiveness (including to drug cues) in adults with psychopathic traits. The reasons for this inconsistency are unclear. It could represent differences in the type of individual identified in the studies with adolescents relative to those with adults. But that would suggest that there is a population of highly aggressive adolescents who are marked by hyper-reward responsiveness. Yet, none have been found. There could be developmental effects. It is notable that when psychiatric comorbidities are examined, the rates of ADHD in the adolescent samples are typically high (>60% Citation42 ). As noted above, ADHD is marked by reduced reward responsiveness relative to comparison adolescents. Citation4 It is unclear the extent to which the pathophysiology of ADHD is ameliorated by adulthood, and much of the adult literature has not involved full psychiatric assessments of the participant samples. But it remains possible that psychopathy in adulthood is not comorbid with ADHD and perhaps the findings of increased reward responsiveness reflect the relationship between increased reward responsiveness and impulsive reward-seeking behavior seen in healthy participants. Citation4 Indeed, the one adult study examining the relationship of reward responsiveness found that increased reward responsiveness was only seen relative to low (not high) impulsive healthy participants Citation50 ; ie, even though the study reported hyper-reward responsiveness this responsiveness was within the healthy range.

In conclusion, this review highlights two forms of dysfunctional neurocognition that incur risks of psychopathology. The first concerns reduced emotional responsiveness and the implications of this for empathy, moral judgments and immoral behavior. This form of neurocognitive dysfunction confers risk for aggression across adolescents and into adulthood. The second concerns reduced reward responsiveness. This is deficient in adolescents with significant conduct problems and probably exaggerates their behavioral difficulties as a function of poor decision-making. It is likely deficient in at least some adults with conduct problems but how pervasive this is the case and whether there is any relationship with psychopathy is currently unclear.

This research was in part supported by the National Institute of Mental Health under award number K22-MH109558 (JB). The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The author has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- FrickPJCallous-unemotional traits and conduct problems: a two-factor model of psychopathy in children199524 Leicester, UK British Psychological Society 4751

- HareRD2003 Toronto, Canada Multi Health Systems

- LynamDRCaspiAMoffittTEet alLongitudinal evidence that psychopathy scores in early adolescence predict adult psychopathyJ Abnorm Psychol2007116115516517324026

- PlichtaMMScheresAVentral-striatal responsiveness during reward anticipation in ADHD and its relation to trait impulsivity in the healthy population: a meta-analytic review of the fMRI literatureNeurosci Biobehav Rev20143812513423928090

- MarshAAFingerECMitchellDGet alReduced amygdala response to fearful expressions in children and adolescents with callous-unemotional traits and disruptive behavior disordersAm J Psychiatry2008165671272018281412

- RubiaK“Cool” inferior frontostriatal dysfunction in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder versus “hot” ventromedial orbitofrontal-limbic dysfunction in conduct disorder: a reviewBiol Psychiatry20116912e698721094938

- VidingESebastianCLDaddsMRet alAmygdala response to preattentive masked fear in children with conduct problems: the role of callous-unemotional traitsAm J Psychiatry2012169101109111623032389

- HarenskiCLHarenskiKAKiehlKANeural processing of moral violations among incarcerated adolescents with psychopathic traitsDev Cogn Neurosci20141018118925279855

- DeeleyQDalyESurguladzeSet alFacial emotion processing in criminal psychopathy. Preliminary functional magnetic resonance imaging studyBr J Psychiatry200618953353917139038

- MeffertHGazzolaVden BoerJAet alReduced spontaneous but relatively normal deliberate vicarious representations in psychopathyBrain2013136Pt 82550256223884812

- DecetyJSkellyLYoderKJet alNeural processing of dynamic emotional facial expressions in psychopathsSoc Neurosci201491364924359488

- DecetyJChenCHarenskiCet alAn fMRI study of affective perspective taking in individuals with psychopathy: imagining another in pain does not evoke empathyFront Hum Neurosci2013748924093010

- CuthbertBNInselTRToward the future of psychiatric diagnosis: the seven pillars of RDoCBMC Med20131112623672542

- HiattKDNewmanJPPatrickCJUnderstanding psychopathy: The cognitive side2006 New York, NY Guilford Press 334352

- BlairRJRFacial expressions, their communicatory functions and neuro-cognitive substratesPhilos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci2003358143156157212689381

- Fusar-PoliPPlacentinoACarlettiFet alFunctional atlas of emotional faces processing: a voxel-based meta-analysis of 105 functional magnetic resonance imaging studiesJ Psychiatry Neurosci200934641843219949718

- MarshAABlairRJDeficits in facial affect recognition among antisocial populations: A meta-analysisNeurosci Biobehav Rev200832345446517915324

- DawelAO'KearneyRMcKoneEet alNot just fear and sadness: meta-analytic evidence of pervasive emotion recognition deficits for facial and vocal expressions in psychopathyNeurosci Biobehav Rev201236102288230422944264

- JonesAPLaurensKRHerbaCMet alAmygdala hypoactivity to fearful faces in boys with conduct problems and callous-unemotional traitsAm J Psychiatry20091669510218923070

- LozierLMCardinaleEMVanMeterJWet alMediation of the relationship between callous-unemotional traits and proactive aggression by amygdala response to fear among children with conduct problemsJAMA Psychiatry201471662763624671141

- WhiteSFMarshAAFowlerKAet alReduced amygdala response in youths with disruptive behavior disorders and psychopathic traits: decreased emotional response versus increased top-down attention to nonemotional featuresAm J Psychiatry2012169775075822456823

- PassamontiLFairchildGGoodyerIMet alNeural abnormalities in early-onset and adolescence-onset conduct disorderArch Gen Psychiatry201067772973820603454

- MierDHaddadLDiersKet alReduced embodied simulation in psychopathyWorld J Biol Psychiatry201415647948724802075

- LammCDecetyJSingerTMeta-analytic evidence for common and distinct neural networks associated with directly experienced pain and empathy for painNeuroimage20115432492250220946964

- HouseTHMilliganWLAutonomic responses to modeled distress in prison psychopathsJ Pers Soc Psychol197634556560993975

- MarshAAFingerECFowlerKAet alEmpathic responsiveness in amygdala and anterior cingulate cortex in youths with psychopathic traitsJ Child Psychol Psychiatry201354890091023488588

- LockwoodPLSebastianCLMcCroryEJet alAssociation of callous traits with reduced neural response to others' pain in children with conduct problemsCurr Biol2013231090190523643836

- MichalskaKJZeffiroTADecetyJBrain response to viewing others being harmed in children with conduct disorder symptomsJ Child Psychol Psychiatry201657451051926472591

- ArbuckleNLShaneMSUp-regulation of neural indicators of empathic concern in an offender populationSoc Neurosci201712438639027362389

- DecetyJSkellyLRKiehlKABrain response to empathy-eliciting scenarios involving pain in incarcerated individuals with psychopathyJAMA Psychiatry201370663864523615636

- RothemundYZieglerSHermannCet alFear conditioning in psychopaths: event-related potentials and peripheral measuresBiol Psychol2012901505922387928

- FairchildGStobbeYvan GoozenSHet alFacial expression recognition, fear conditioning, and startle modulation in female subjects with conduct disorderBiol Psychiatry201068327227920447616

- CohnMDPopmaAvan den BrinkWet alFear conditioning, persistence of disruptive behavior and psychopathic traits: an fMRI studyTransl Psychiatry20133e31924169638

- BirbaumerNVeitRLotzeMet alDeficient fear conditioning in psychopathy: a functional magnetic resonance imaging studyArch Gen Psychiatry200562779980515997022

- HwangSNolanZTWhiteSFet alDual neurocircuitry dysfunctions in disruptive behavior disorders: emotional responding and response inhibitionPsychol Med20164671485149626875722

- ShaneMSGroatLLCapacity for upregulation of emotional processing in psychopathy: all you have to do is askSoc Cogn Affect Neurosci201813111163117630257006

- AndersonNESteeleVRMaurerJMet alDifferentiating emotional processing and attention in psychopathy with functional neuroimagingCogn Affect Behav Neurosci201717349151528092055

- O’DohertyJPCockburnJPauliWMLearning, reward, and decision makingAnnu Rev Psychol2017687310027687119

- BlairRJRTraits of empathy and anger: implications for psychopathy and other disorders associated with aggressionPhilos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci20183731744

- BjorkJMChenGSmithARet alIncentive-elicited mesolimbic activation and externalizing symptomatology in adolescentsJ Child Psychol Psychiatry20105182783720025620

- SchwenckCCiaramidaroASelivanovaMet alNeural correlates of affective empathy and reinforcement learning in boys with conduct problems: fMRI evidence from a gambling taskBehav Brain Res2017320758427888020

- FingerECMarshAABlairKSet alDisrupted reinforcement signaling in the orbital frontal cortex and caudate in youths with conduct disorder or oppositional defiant disorder and a high level of psychopathic traitsAm J Psychiatry20111682834841

- WhiteSFPopeKSinclairSet alDisrupted expected value and prediction error signaling in youths with disruptive behavior disorders during a passive avoidance taskAm J Psychiatry2013170331532323450288

- CrowleyTJDalwaniMSMikulich-GilbertsonSKet alRisky decisions and their consequences: neural processing by boys with Antisocial Substance DisorderPLoS One201059e1283520877644

- RubiaKSmithABHalariRet alDisorder-specific dissociation of orbitofrontal dysfunction in boys with pure conduct disorder during reward and ventrolateral prefrontal dysfunction in boys with pure ADHD during sustained attentionAm J Psychiatry2009166839418829871

- CohnMDVeltmanDJPapeLEet alIncentive processing in persistent disruptive behavior and psychopathic traits: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study in adolescentsBiol Psychiatry201578961562425497690

- VeroudeKvon RheinDChauvinRJet alThe link between callous-unemotional traits and neural mechanisms of reward processing: An fMRI studyPsychiatry Res Neuroimaging2016255758027564545

- VollmBRichardsonPMcKieSet alNeuronal correlates and serotonergic modulation of behavioural inhibition and reward in healthy and antisocial individualsJ Psychiatr Res201044312313119683258

- HoskingJGKastmanEKDorfmanHMet alDisrupted prefrontal regulation of striatal subjective value signals in psychopathyNeuron201795122123128683266

- GeurtsDEvon BorriesKVolmanIet alNeural connectivity during reward expectation dissociates psychopathic criminals from non-criminal individuals with high impulsive/antisocial psychopathic traitsSoc Cogn Affect Neurosci20161181326133427217111

- PujaraMMotzkinJCNewmanJPet alNeural correlates of reward and loss sensitivity in psychopathySoc Cogn Affect Neurosci20149679480123552079

- GregorySBlairRJFfytcheDet alPunishment and psychopathy: a case-control functional MRI investigation of reinforcement learning in violent antisocial personality disordered menLancet Psychiatry20152215316026359751

- FingerECMarshAAMitchellDGVet alAbnormal ventromedial prefrontal cortex function in children with psychopathic traits during reversal learningArch Gen Psychiatry200865558659418458210

- PrehnKSchlagenhaufFSchulzeLet alNeural correlates of risk taking in violent criminal offenders characterized by emotional hypo- and hyper-reactivitySoc Neurosci20138213614722747189

- KoobGFVolkowNDNeurobiology of addiction: a neurocircuitry analysisLancet Psychiatry20163876077327475769

- DenommeWJSimardIShaneMSNeuroimaging metrics of drug and food processing in cocaine-dependence, as a function of psychopathic traits and substance use severityFront Hum Neurosci20181235030233344

- CopeLMVincentGMJobeliusJLet alPsychopathic traits modulate brain responses to drug cues in incarcerated offendersFront Hum Neurosci201488724605095

- VincentGMCopeLMKingJet alCallous-unemotional traits modulate brain drug craving response in high-risk young offendersJ Abnorm Child Psychol2018465993100929130147

- BlairRJREmotion-based learning systems and the development of moralityCognition2017167384528395907

- BlairRJRA cognitive developmental approach to morality: Investigating the psychopathCognition1995571297587017

- AharoniESinnott-ArmstrongWKiehlKWhat's wrong? Moral understanding in psychopathic offendersJ Res Pers20145317518126379315

- AharoniEAntonenkoOKiehlKADisparities in the moral intuitions of criminal offenders: The role of psychopathyJ Res Pers201145332232721647247

- KoenigsMKruepkeMZeierJet alUtilitarian moral judgment in psychopathySoc Cogn Affect Neurosci20127670871421768207

- BocciaMDacquinoCPiccardiLet alNeural foundation of human moral reasoning: an ALE meta-analysis about the role of personal perspectiveBrain Imaging Behav201711127829226809288

- FedeSJBorgJSNyalakantiPKet alDistinct neuronal patterns of positive and negative moral processing in psychopathyCogn Affect Behav Neurosci20161661074108527549758

- MarshAAFingerECFowlerKAet alReduced amygdala-orbitofrontal connectivity during moral judgments in youths with disruptive behavior disorders and psychopathic traitsPsychiatry Research2011194327928622047730

- HarenskiCLHarenskiKAShaneMSet alAberrant neural processing of moral violations in criminal psychopathsJ Abnorm Psychol2010119486387421090881