Abstract

The way in which societies around the globe are governed is changing towards more flexible and networked forms where the government is not the sole and main responsible actor in the organisation, funding, delivery and evaluation of public services. Analysing the new roles of philanthropic organisations, think tanks and business organisations is a key task in order to understand the expansion of neoliberal ideas and solutions in the field of education policy. Taking as a starting point the set of ideological pillars and discursive practices of the Spanish neoliberal think tank Foundation for Social Studies and Analysis (Fundación para el Análisis y los Estudios Sociales, FAES) and its networks of academics and experts, this article aims to offer a deeper understanding of the processes through which new models of public management and market-based solutions are being promoted and enacted in the Spanish educational arena. To do this, we will experiment with tools derived from what is known as ‘network ethnography’, a new methodological approach that combines aspects of Social Network Analysis with more traditional ethnographic methods.

Antonio Olmedo is a British Academy Newton International Fellow based at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Institute of Education, University of London, United Kingdom. His research interests and publications rest within the field of Education Policy Analisys and Sociology of Education, more concretely in the relation between Education Policy and social class: social inequalities and segregation; neoliberal policies and the creation of quasi-markets; and global networks, international organisations, policy advocacy, philanthropy, and ‘edu-businesses’: international education policy and emerging patterns of access, opportunity and achievement in education. Email: [email protected]

Eduardo Santa Cruz Grau is a Chilean sociologist and researcher at the University of Granada, Spain. He is currently finishing his PhD. He is also a researcher at the Interdisciplinary Research Programme in Education (PIIE) and the Research Centre in Education in the University UCIFN, both in Chile. He has published several articles and contributions to books in the field of sociology of education, education policy, education reform, media and citizenship. Email: [email protected]

The field of education policy is changing rapidly in Spain. In the contemporary scenario, new policy spaces are being opened where new and rehashed forms of policy arise. These transformations do not respond to an intrinsic logic within the own nature of the social and political fields, but to the existence of synergies and the intertwined work of individuals and organisations in a context of power struggles. In some cases, these changes are the result of processes of trial and error, forced by a climate of immediacy and the need for specific actors to legitimise certain positions and perspectives in the short term. In this sense, this new environment should not be understood as the simple product of a deliberated plan but, on the contrary, as the result of a convulsed mix of interests and strategies of multiple sectors with different aims and views of the world, which leads to the creation of apparently “incoherent” alliances (Apple Citation2001b) but also uncertain and untested solutions to social problems (Ball Citation2009).

This article addresses some of the issues involved in the ongoing changes in the forms of governance in the case of Spain. More specifically, we are interested here in the embedded mechanisms and networked actors and settings through which ideas and policies travel (Ozga & Jones Citation2006). Using the case of FAES, one of the most active neoliberal foundations in Spain, the paper aims to illustrate the role of Spanish think tanks in the construction of circuits of influence and policy advocacy in the field of education. To do this, we will experiment with tools derived from what is known as ‘network ethnography’ (see Howard Citation2002), a new methodological approach that combines tools from Social Network Analysis (SNA) with more traditional ethnographic methods. As Howard suggests, “whereas social network analysis renders an overarching sketch of interaction, it will fail to capture detail on incommensurate yet meaningful relationships” (Howard Citation2002, 550). Complementing SNA tools with the use of qualitative approaches could help overcome that limitation, as the latter “add an awareness of context which aids the interpretation of network maps and measures; they add an appreciation of the perception of the network from the inside; and an appreciation of the content of ties in terms of quality, meaning, and changes over time” (Edwards Citation2010, 24). The challenge is therefore to design new conceptual categories and methods that would help us develop a broader understanding of such relationships and address the ‘social’ dimension of policy networks.

Network ethnography aspires to embrace those issues. This approach should be situated within “a broad set of epistemological and ontological shifts across political science, sociology and social geography which involve a lessening of interest in social structures, and an increasing emphasis on flows and mobilities” (Ball 2012, 5). Alongside, it highlights the new configuration of social life, which has become increasingly “networked” (Urry Citation2003). According to this emerging paradigm, the network “become(s) the foundational unit of analysis for our understanding of the global economy” (Dicken et al. Citation2001, 89). Methodologically in this paper the term ‘network’ will be used in a dual sense (Ball 2012). On the one hand, it is purely a ‘method’, that is “an analytic technique for looking at the structure of policy communities and their social relationships”. On the other hand, networks are also ‘conceptual devices’; they are “used to represent a set of ‘real changes’ in the forms of governance of education, both nationally and globally” (Ball 2012, 6).

Within this framework, as Dicken et al. (Citation2001, 89) point out, “such a methodology requires us to identify actors in networks, their ongoing relations and the structural outcomes of these relations”. The research work presented in this paper was designed to embrace those tasks in three stages. First, a series of extensive Internet searches were conducted with the aim to identify the main players involved in the Spanish education policy arena. The main sources of information in this first stage were mainly institutional and organisations’ websites, events, newspaper articles, personal and collective blogs, YouTube videos, Twitter and Facebook. The information obtained through those searches was used to build and analyse different policy networksFootnote1 and to identify significant cases within them. The second stage of the research concentrated on the selection of a particular case study within the network. At this point, a new iteration of Internet searches and semi-structured interviews with key players involved were conducted with the aim of generating a better understanding of the networking and governance processes around the selected case. The choice of FAES as the focus of analysis in this paper was made due to its character as a ‘generative node’ (see below), its centrality within the network and the broad range of relationships and activities in which this think tank is involved. The connections, contacts and the configuration of the agendas of those organisations and individuals are discussed in the first two sections of the paper. All the data generated at this stage of the research were stored in a second databaseFootnote2, which provided the basis for further discourse analysis. The final two sections of the paper focus on the discourses and ideological pillars of FAES and its networks of academics and experts. There, we analyse the diverse range of publications, events’ programmes, pamphlets and other informative documents disseminated by the foundation. At this point, the materials were divided into two main axes: the third section examines those texts that promote the idea of crisis both in terms of the structure and the contents and values within the education system; finally, the fourth and final section analyses the new models of public management and market-based solutions that are actively promoted by the foundation.

An era of changes: The new Spanish political context welcomes neoliberal logics

Over the past three decades, Spain has experienced a rapid set of changes in social, economic and political terms. The end of Franco's dictatorship in the mid-1970s opened up new opportunities for a number of actors – left wing political parties, trade unions, civil rights activists, civil groups etc. – that had remained in a prolonged state of waiting and operated in the dark. The death of the dictator in 1975 meant the beginning of a long transitional process to democracy which started with the establishment of a parliamentary monarchy and the first constitutional referendum in 1978. The main challenge that the successive democratic governments had to face was the lack of correspondence between the social structures inherited from francoism and the absence of institutional means for state intervention. The nascent democratic state felt the urge to find answers to a growing, incoherent and structurally contradictory set of social and economic demands. Bonal (Citation1995) suggests that during the first two decades of democratic transition Spain shared the main two characteristics of what Santos (1985; 1992) classified as “semi peripheral societies”. First, there is an apparent institutional and structural disjunction between social production and social reproduction, which are translated into gaps between modes of social consumption and the production system. Second, the newborn state is faced with a high degree of internal autonomy at the local, regional and national levels, which does not translate in terms of its strength as a legitimate force.

Throughout this period and up to the present day, education has continuously found itself at the centre of social and economic reforms, but also as the target of all criticisms and one of the most recurrent explanations of the failure of the inability of the Spanish economy to finally flourish. In this convulsed climate, Bonal (Citation1995, 210) advises that the processes of educational reform should be understood “more [as] a political reaction than a political action” and imply a number of internal contradictions that education policy should face. The first of those contradictions relates to the economic sphere. The need for modernisation on all fronts collides with a general picture defined by a deep financial crisis, which is particularly clear during the oil crisis at the beginning of the 1970s that affected the majority of industrialised countries and later on during the European economic crises at the beginning of the 1990s, which served as the final spark in order to reignite the criticisms of the welfare state system throughout most countries on the Old Continent. Second, there is conflict in the social dimension between the social demand for expanding the outreach of public services and the lack of democratisation in the mechanisms of participation and access to those services. The third contradiction regards the cultural necessity to build and reinforce a shared national identity while, at the same time, addressing the existence of the existing social diversity between different social groups and geographic regions. Finally, there is a contradiction in terms of the rationality of governance given the urge to move from a highly bureaucratised and top-down controlled system of input allocation to more productive rationalities based on the introduction of market-based mechanisms.

The changes implied here are part of a broader reconfiguration of the model of state, its functions and the way in which its relationships with other spheres are established (Jessop Citation2002). As a result of all the above, new players are arising and hybrid spaces are being created that blur the responsibilities and boundaries of what is being traditionally understood as ‘the public sphere’. This entails a new conception of the way the contemporary ‘problematic of government’ (Foucault, Citation1979) is understood, requiring new conceptual and methodological tools. On one hand, the new paradigm implies a first move from the opposition between anarchy and bureaucracy, the traditional market vs. state division, into new hybrid and reflexive forms of governance: heterarchies. According to Jessop, the concept of heterarchy, as a new mode of governance, implies “the reflexive self-organization of independent actors involved in complex relations of reciprocal interdependence, with such self-organization being based on continuing dialogue and resource-sharing to develop mutually beneficial joint projects and to manage the contradictions and dilemmas inevitably involved in such situations” (Jessop Citation2002, 217).

On the other hand, the appearance of new players in the national and global political arena involves a redefinition of the roles assigned to traditional actors and the renegotiation of the boundaries between their spheres of action. This does not mean that the old actors, and particularly the state, are less important or even less influential. On the contrary, these changes might have even reinforced their capacity to govern individuals and their practices “at a distance” (Miller & Rose Citation2008). As Jessop suggests, “the new state form (considered as a form-determined, strategically selective condensation of the changing balance of political forces) is playing a major role in the material and discursive constitution of globalizing, networked, knowledge-based economy that its activities is seeking to govern” (Jessop Citation2002, 95–96). This second move is known as the shift from government to new modes of metagovernance, which entails an “increased salience of the state in organizing the conditions of self-organization so that it can compensate for planning and market failures alike in an increasingly networked society” (Jessop Citation2002, 96). The new form of the state implies a new conception of its role as a ‘market-maker and facilitator’, acting “more and more as a collective commodifying agent […] and even as a market actor itself” (Cerni Citation1997, 267), where the market should be understood as a policy technology that modulates dynamics of power flows (Ball Citation2007).

Neoliberal policy travels: The role of think tanks and networks

Those paradigmatic changes and processes of constant reorganisation reinforce the idea that policy ideas do not move in a vacuum. They are social and political creations that are told and re-told in specific spaces and locations and, then, move through and are adapted by networks of social relations or assemblages (Ball & Junemann Citation2012). In the case of Spain, the inconsistent context of contradicting expectations and demands described in the previous section serves as a fertile ground for the gradual introduction of neoliberal policy technologies. Indeed, during the 1990s and the first decade of the 21st century, public policy in Spain was moving towards a model based on competition, efficiency, choice and performativity (Ball Citation2007), configuring what Calero (Citation1998) designated as the Spanish “incomplete quasimarket”. The measures implemented under this new model of management of public services have also affected education (Bernal Citation2005; Calero & Bonal Citation1999; Olmedo Citation2008). Simultaneously, these changes in the mode of governance facilitate the appearance of new players in the educational arena. As Sorensen and Torfing (Citation2007, 3) point out, “policy, defined as the attempt to achieve a desired outcome, is a result of governing processes that are no longer fully controlled by the government, but subject to negotiations between a wide range of public, semi-public and private actors”. From this perspective, policy narratives and policy advocacy are therefore defined in an interconnected and networked form and should be understood as part of vibrant global socio-political and financial relations that are maintained and extended both locally and virtually.

Alongside governments and other social initiatives, for-profit businesses and their philanthropic foundations are gaining ground in the delivery and enactment of particular education policies in Spain (Olmedo 2012). They configure policy networks that are the joining up of ideology, policies and politics, advocacy, philanthropy and businesses (Ball Citation2007). This new form, the network, represents a new way of thinking about the process of policy creation and policy borrowing. Thinking in networked terms helps us comprehend the complexity of the dynamics involved in contemporary policy making. Understanding policy movements in this sense implies looking at policy and policy transfer not as “the voluntaristic acts of unconstrained, rational transfer agents freely ‘scanning’ the world for objectively ‘best’ practices and not by focusing on and fetishizing policies as naturally mobile objects”, but as “paradoxically structured by embedded institutional legacies and imperatives” (McCann Citation2011, 109). Through them, ideas and solutions, policy technologies and decisions flow, giving shape to new ways of understanding society and its institutions. The need for a new justification for the expansion of capitalism on a global scale is the main driver of the configuration and activities of such networks. In this sense, we see networks as a set of interconnected places, spaces, organisations and individuals, or groups of individuals, which conform to “new techno-economic paradigms” (Jessop Citation2002, 95) and new forms of governance.

In the case of Spain, the work of think tanks and other interest groups (civil and professional associations, philanthropic foundations etc.) is key to understanding the emergence and shape of policy and advocacy networks. These organisations operate at a “meso-level” (Bonal Citation2000), connecting the interactions between the activities and decisions of policy makers and the level of the everyday practices of individuals and social groups. As Bonal (Citation2000, 202) suggests, “ethnographic accounts of interest groups’ actions and the strategies they employ to penetrate the State agenda have contributed to a better understanding of educational change”. The discourses of such organisations take shape a set of speeches, activities, texts, agendas, connections etc., which in many cases constitute the ‘missing link’ that explains the apparently incoherent principles of certain political reforms and the continuities and discontinuities of such policy processes. Their activities cover the whole spectrum described by Keck and Sikkink (Citation1998) in relation to role of advocacy in policy networks: information politics (the capacity to create relevant information for policy makers); symbolic politics (the capacity to create stories and recall symbols and actions that are meaningful for particular groups or sectors of society); accountability politics (the capacity to hold policy actors accountable for their promises and commitments); and, finally, leverage politics (the capacity to exert an influence over and direct policy making processes towards a certain direction).

The Foundation for Social Studies and Analysis (Fundación para el Análisis y los Estudios Sociales, FAES), as well as the other organisations mentioned below, constitutes a good example of neoliberal policy advocacy in the Spanish landscape. As stated on its website, FAES’ portfolio and agenda are aimed towards the consecution of a neoliberal society:

FAES believes in economic freedom and upholds the concepts of private property, market economies and free trade – concepts that are both inalienable rights of a free society and the key drivers of prosperity and progress. Its liberal persuasions mean that it also upholds the role of the State as guarantor of individual freedomFootnote3.

Individual rights, freedom (with an emphasis on economic freedom), competition and markets are the central targets of its activities, and this all has a direct translation within the field of public policy:

The liberal convictions that inform the organisation mean that FAES has an aim to improve the quality of government policy, rationalise the public sector, enhance freedom of choice and strive to keep the cost of public services as low as possible for the taxpayer. Our analyses always take account of the fact that individual responsibility is inalienably linked to freedomFootnote4.

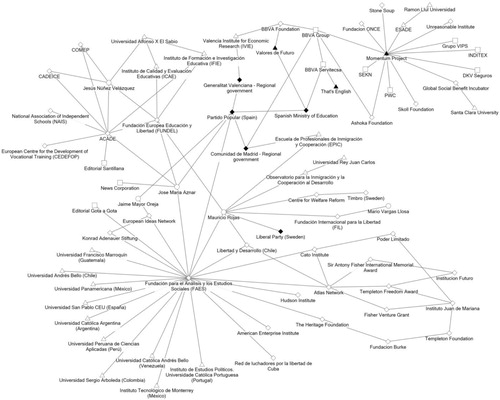

FAES maintains active links with local and global policy actors, individuals and organisations (see ). The analysis of its connections and agenda suggests the intention to be constantly present and exert an influence on day-to-day Spanish political life (see Olmedo 2012; also Viñao Citation2012). Within the field of education, its network of collaborators includes academics, experts, international political leaders, education officials from different regions governed by the conservative party, student representatives and others who either work regularly or collaborate sporadically with the foundation.

Since its creation in 1989, the foundation has been openly linked to the Spanish conservative party (Partido Popular). FAES’ founder and current president, Jose Maria Aznar, served as Spanish Prime Minister from 1996 to 2004; the vice-president, Maria Dolores de Cospedal, is the current General-Secretary of the party; and the foundation's board of trustees is plagued with active and retired politicians (as, for instance, the current Prime Minister, Mariano Rajoy; the Minister of Health, Ana Mato; the former Ministers of Education, Esperanza Aguirre and Pilar del Castillo; and other ex-ministers, such as Pio Cabanillas and Federico Trillo, former Minister of Defence and current Spanish ambassador to the UK.

The increasing number of seminars, meetings, conferences etc. organised by FAES, as well as the growing collection of published documents and periodical publications (see the next section), highlights the impact of FAES on the ongoing education reform during the last three decadesFootnote5. These activities are physical and virtual spaces of/for policy advocacy, designed with the intention of inoculating new ideas and solutions in the discourse of key influential policy actors as well as enriching the foundation's social capital and further potential range of influence. Two examples illustrate this argument. First, since 2003 and with a yearly cadence, FAES has organised a forum of evaluation and analysis of key areas and emerging political challengesFootnote6. The debates at Campus FAES revolve around multiple themes within the fields of the economy, justice, institutional reform, social services provision etc. Education is also a key area of interest and, strengthening ever more the character of the seminars as a key site for policy advocacy, the current conservative Minister of Education, Culture and Sport, José Ignacio Wert, who had been a regular collaborator of FAES in the past, has chosen the last two editions of the Campus to present and discuss the new project for reforming the education systemFootnote7. The second example of the presence of FAES in the political arena relates to the foundation's strategy to embrace and connect with individuals that currently occupy or that are expected to exert in the future leading political positions. This is the case of one of the most influential ideologists of the conservative party in educational matters: Francisco López Rupérez. He is considered to be one of the main promoters of neoliberal policy technologies during Aznar's conservative government (see, for instance, Bolivar Citation1999). López Rupérez has held different political positions at international, national and regional levelsFootnote8, and was appointed by the current government as president of the State Board of Education in 2012. He is also one of FAES’ most influential collaborators and assiduous writers.

These networking and advocacy activities are performed both at institutional and personal levels. In many cases, it is necessary to consider the contribution and movements of individual actors in order to understand the otherwise cold and artificial links between different institutions. These individuals mobilise their personal web of contacts and influence and, by doing so, contribute to increasing the institutional social capital of the organisations they work for. Their work is therefore key to situating those organisations in favourable positions from where they can exert their advocacy activities. In 2011, for instance, the foundation published a book entitled “Reinventing the Welfare State”. The author of the book is Mauricio Rojas, a Chilean/Swedish politician, political economist and market advocate. Since 2002 Rojas has been a member of the Riksdag (the Swedish National Parliament) for the Liberal People's Party and also member of the Constitutional Committee. Previously, he had been the director of the Centre for Welfare Reform at the Stockholm-based think tank of which he became president later on. He has written several books and articles in which he analyses the failure of the welfare state and advocates market-based solutions in the public sector. Jose Maria Aznar, the Spanish ex-president and founder and current president of FAES, wrote the prologue of the book and used it to emphasise his ideological perspectives:

Sweden's reforms have enabled the country to make a transition from an obsolete and outdated Welfare State to a much healthier Welfare Society, capable of offering better standards of life to its citizens through more and better jobs, less taxes and greater freedom when choosing education, health care and social servicesFootnote9.

Both Aznar and Rojas have been awarded the “Education and Freedom” prize granted annually by ACADE (an association of independent private schools) and its philanthropic arm FUNDEL (Education and Freedom European Foundation). Moreover, FAES, ACADE and FUNDEL work closely together in different ways. They promote each other's activities on their websites; disseminate and organise courses, conferences and seminars together; collaborate in the elaboration of publications, book launches, journals etc. ACADE and FUNDEL actively support the implementation of market mechanisms within the field of education. As in the case of FAES, their objectives revolve around the same beliefs and principles: freedom (understood as freedom of school choice; freedom of creation of schools; freedom of teaching) and what they call equal opportunities (operationalised through a system of schools vouchers or tax rebate)Footnote10. The four domains of policy advocacy mentioned above can also be easily found in the activities and agendas of these organisations. Currently, ACADE effectively represents over 3,800 private schools but its aims cover a much broader range of functions within the political arena. As stated on its website, ACADE's commitments with its members, and more broadly with Spanish society, could be summarised asFootnote11:

To represent, manage and defend the professional and economic interests of member schools.

To elaborate recommendations and principles on education policy.

To collaborate with State instances at different levels.

To negotiate memorandums of understanding and collective bargaining agreements.

To promote unity among edu-entrepreneurs and school groups.

To carry out research and studies related to the educational field.

To promote and execute cultural, sports, educational, technical and formative activities; as well as the publication and promotion of texts, and the organisation of conventions, conferences, symposiums and seminars.

The president of both organisations, Jesús Núñez Velázquez, is at the same time president of CADEICE (Private Schools Associations Confederation of the European Union) and the European Vice-president of COMEP (World Confederation of Private Education). Like ACADE and FUNDEL, the advocacy work of these two organisations also focuses on strengthening the participation and presence of private initiatives within education. Both institutions exert political leverage at an international level (European Commission, UNESCO, World Bank etc.). CADEICE, for instance, openly states its intention to consolidate as “a lobby of influence in the European Union, so that private education is taken into account by the policy and the European legislation”Footnote12. Similarly, COMEP states its aim to “support and preserve the creation and existence of private educational entities, by performing those actions which may best lead to the defence of the rights of such entities, and by fostering the establishment of national legislation aimed to ensuring the Integration of institutions of private education in every country”Footnote13.

Finally, FAES is also part of the ATLAS Network, a global network of more than 400 pro free market organisations in over 80 countriesFootnote14, and works closely with a number of other neoliberal think tanks, universities, political parties and individuals that share the same principles and purposes. The relationships between the organisations are established and extended through the common exchange of ideas, publications and experts, and the co-organisation of seminars and summits. The participation within wider networks, both in the present time and in the past, allows the foundation to accumulate symbolic and social capital, which varies in terms of the ‘quality’ of the partners that populate them. FAES’ representatives attend the meetings of influential American neoliberal institutions such as the CATO Institute, the American Enterprise Institute, the Heritage Foundation and the Hudson InstituteFootnote15. In Europe, the foundation was one of the founders of, and still plays a leading role within, the European Ideas Network. Also, they keep alliances with other European neoliberal foundations such as the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung and the Friedrich Von Hayek Stiftung in Germany, the Centre for Policy Studies and the Institute for Economic Affairs in the UK, and the Copenhagen Institute and Timbro in the Nordic countriesFootnote16.

FAES is also a good example of a “generative node” (Ball and Olmedo Citation2012). These are special nodes within networks that operate as network catalysts and connectors conceived to establish new “networks within networks” (Ball 2012), facilitating new relationships, creating spaces, both physical and virtual, and serving as an effective channel to communicate and disseminate potential profitable areas. The analysis of such generative nodes opens interesting possibilities to understand the ways in which policy ideas are transmitted and actors are bound within wider networks. Through the establishment of links and partnerships with other institutions, the foundation aims to strengthen its outreach and presence in new spaces and new territories. FAES is particularly active in Latin America where it has developed its own network of institutions. Among those, there are other neoliberal think tanks and foundations such as Libertad y Desarrollo in Chile, and liberal political parties associations like the Organización Demócrata Cristiana de Lationamérica. The foundation has even founded its own Latin American Network of Former FAES Scholarship Recipients:

The Foundation undertakes a considerable amount of work in close cooperation with these institutions, helping further disseminate the ideas and aims of liberal thinking that are core to FAES’ ideology. The Foundation is also extending its network of collaborators by adding ex interns and FAES Campus students, grouping them together in different networks. The aims of FAES networks include promoting the basic ideas of liberal democracy in Latin America, where FAES runs several different networks for joint work and collaborationFootnote17.

The agendas and activities of the organisations analysed in this section stress the importance of making the right choices at the right moment when choosing who and where to work with. This relates to Sheppard's concept of “positionality” (Sheppard Citation2002) that highlight the importance of taking into account the relational connection between place, scale and networks in the global economy. The dynamics involved here highlight the need to overcome traditional dialectics that might not be of use anymore, or at least not as confronted and exclusive concepts as they were in the past. Spaces and places, movement and fixity, virtual and embodied, immediacy and history, fragile and stable, form the new coordinates of a multidimensional plane that configures the new landscape for analysing policy.

Making sense through alarm and fear: FAES and the eternal Spanish educational crisis

As suggested above, networks can also be seen as “architectures of policy positions” (Gale Citation2001, 389), hosting discourses that generate “domains of validity, normativity and actuality” (Foucault Citation1972, 68). These discourses are part of processes of the “construction of sense, creation and circulation of meanings, of practices of redefinition, in which national and transnational actors are involved” (Mato Citation2007, 38). According to Fairclough and Wodak (Citation1997), discourses can be described as social practices that imply a certain relation between a discursive event, a particular linguistic style, and the situation, institutions and social structures within which they are embedded. Such a linguistic style is simultaneously constituted by social identities, social relations and systems of knowledge and believes (Fairclough Citation2003). That being said, discursive events are socially configured and, therefore, the different institutions, domains, societies and groups within them generate discursive practices that coexist, contrast and quite often compete with each other (Fairclough Citation2008). Therefore, discourses “are configured as both as possibility and limitation, inclusion and exclusion. In its midst, the meaning of terms and signifiers are modified; combining them in peculiar ways, alternative thought processes are fixed and others are discarded. This framework of exclusions and inclusions, which constitute the discourse, create antagonistic ties with other discourses” (Rodríguez Citation2003, 119). In practice, a number of social discourses are generated, disputing their capacity to represent the world, produce subjectivities and define relationships within societies (Thomas Citation2002). In a mediated social environment (Verón Citation2001), such us the current one, the function of discourse both within the social system and in the common everyday life becomes central (Fairclough et al. Citation2004).

Institutions such as FAES participate in the public sphere precisely through the production and distribution of discursive practices covering diverse areas of the social sphere and helping to influence and consolidate a notion of common sense within the Spanish society. Their wish to build hegemonic processes around a specific social project is expressed through the setting up of institutional practices that emphasise the consolidation of social networks (see above) and the elaboration of plausible narratives around images, representations and ideas that pertain to neoliberal political doctrines. To fulfil this objective, the foundation uses a multifarious range of texts, social spaces and institutional resources. These are enacted through the organisation of meetings, debates, seminars, conferences, training courses and a wide collection of publications, some of which are periodicals such as ‘Cuadernos de Pensamiento Politico’ and ‘Papeles FAES’, while others do not follow a fixed periodicity such as the foundation's own books and from the publisher “Gota a Gota” (translated into English as “Drop by Drop”), which is also a good metaphor to describe FAES’ modus operandi and theory of change.

The foundation's interest areas cover a broad range of topics in the field of public policy, which vary with the dynamics of the political course and other related social problems. In the case of education, its main preoccupations have been centred in areas such as the critique of comprehensive education and school failure, school vouchers and freedom of school choice for families, the scope of political responsibilities of regional governments, and citizenship education. In total, over the last eight years, the foundation has published 17 articles and 4 book reviews in its periodical journal and 12 short monographs around different educational themes. A total of 23 authors from different institutions and areas of expertise have been involved in those publications.

The analysis of the discursive practices of FAES in the field of education is relevant due to the significant influence the foundation has within the network of neoliberal and neoconservative institutions and other political, social and economic agents presented in the previous section. An analysis of its pamphlets, books, articles and periodical publications shows the existence of two main axes that structure their discourse around the most contingent and specific aspects of education policy. In other words, those axes conform to a set of ideas, images and representation and offer a coherent account about the situation of education in Spain. They are articulated and mixed in order to underline the need to introduce market mechanisms and incentives within the Spanish educational system and, simultaneously, to recover an alleged tradition and cultural unity of values and pedagogies within the curriculum. However, it is important to acknowledge the fragmented, non-linear and, at times, even incoherent nature of FAES’ discursive traces.

The first axis amalgamates a series of ideas and images about an educational system that is in a constant profound crisis, burdened by the inefficacy in the consecution of its proposed aims and the moral and cultural decay of society as a whole. This description is shared by the authors promoted by FAES and seems stable throughout the analysed period. Proof of this is found in the titles of some of their works: The great rupture of education in Europe (Nasarre Citation2010); In the name of equity, ignorance cannot be extended (Delibes Citation2005); Education for citizenship or attack to democracy? (González Citation2008); The ruin of Spanish education (Orrico Citation2005); The 2009 PISA report. Spain worsens its results (Sainz et al. Citation2011); Four years of backwards movement in Spanish education (Delibes Citation2008); and Back to ignorance (Vermoet Citation2007). As the following extract shows, the quality of the education system is described as decadent allegedly due to the implementation of social democratic policies and not a more general historical backwardness provoked by decades of conservative policies under Franco's dictatorship:

(…) to appeal to our inferior level of cultural and socioeconomic development, in short, to our historical backwardness as the essential factor, is an ugly excuse in order to avoid recognising that the only educational model that has been applied nonstop since 1990 is not producing the results that were expected by those who conceived it (López Rupérez Citation2008, 5).

This notion of backwardness and decline is built by collecting a set of different phenomena which do not share a same cause, and organising them around an account that gives them apparent coherence and unity. The final objective is to achieve a discursive hegemony by describing and connecting both the present and the past of education in Spain.

(…) since the promulgation of the LOGSE by the socialist government of Felipe Gonzalez in 1990, we have seen how the Spanish educational system has sunk gradually in the incompetence, the destruction of knowledge, the demoralisation of professionals, the demotivation of students, the exponential increase of indiscipline, the bad ways, the unpunished violence, and, in sum, the general corrosion of an education system that until that moment has functioned reasonably well (Orrico Citation2005, 27).

This discourse articulates a set of dramatically negative cultural stereotypes. The trigger of all those problems is the manifested overcrowding of schools and classrooms due to the increase in the compulsory schooling age of the pupils put in place by the Socialist Party. Those stereotypes are based on the decontextualised generalisation of the conduct of discrete and individual cases. These affirmations are not questioned or put into a broader social perspective within the same discourse. Instead, they are presented as axioms from which the arguments are built. This is the case of claims about the existence of indiscipline and violence in classrooms and the demoralisation of educational professionals. In short, these are argumentative strategies, the topoi of the stories according to Wodak (Citation2003) that reject the present from an idealised evaluation of the past. The idea of a generalised decay within the educational sphere is reinforced by the discursive association with processes that take place in parallel spheres of society also assessed as negative, such as the homosexual marriage, gender equity policies, the growth of immigration, or issues related to multiculturalism.

A basic characteristic of FAES’ discourse across all fields is its tendency towards polarisation and, in most occasions, the reiterative use of the we/they dichotomy. This discursive strategy is based on the establishment of racial differences between those who are considered part of their group and whose positive characteristics are extoled, and those who are refused as estrangers, the ‘others’. The latter are represented systematically in terms of negative values, characteristics and actions (Van Dijk 2006). This dynamic of binary constructs is typical of political and ideological discourses and, in our case, it also affects the field of education.

As stated above, the first binary opposition corresponds to the juxtaposition between tradition and change. As Apple (Citation2001b, 21) points out in relation to the United States, “against the fears of moral decay and social and cultural disintegration, there is a sense of a need for a ‘return’”. In a number of FAES publications, the authors insist on the fact that the crisis in education is a consequence of the rupture of a prior social and educational order that was already working well in relation to the needs of Spanish society. However, this process is claimed to be simultaneously taking place in other countries within Occidental Europe, where there is “a cultural battle of colossal dimensions (…) around ideas, values and beliefs, where education is one of the key stages” (Nasarre Citation2010, 147). For that same reason, multiculturalism is rejected given the divisive effects it has in a supposedly united society that shares common cultural roots. There is a similar position on local and regional identities which, from this perspective, threaten the unity of such “imagined communities” (see Anderson Citation1993), be they Occidental, European or Spanish.

This cultural dispute reflects the lack or loss of consensus over basic values that structure society and highlights a problem of legitimacy in the social order. From their perspective, education is “under attack” (Pericay Citation2005) by those who support the demands of social egalitarianism, pedagogic modernisation and the recognition of cultural diversity. Seen that way, the crisis in education stems from the inability of the system to teach the set of values needed to govern society. As one of the texts points out, “youngsters have been denied by us the cultural tradition that helped us live, mistaking the democratisation of culture with a fake substitute” (Orrico Citation2005, 53). The long shadow of this social and cultural crisis also reaches and modifies the sphere of education, creating a severe problem of efficiency and lack of sense in educational activity.

Therefore, authority and tradition. Here are the two classic pillars of education that modern pedagogy has renounced to. (…) 1968, since then, and with different rhythms in different countries, in the classrooms of half the continent, authority has been substituted step by step by false egalitarianism, and tradition by the mirage of modernity (Pericay Citation2005, 58).

In other words, the hegemony of political and pedagogical discourses that reinforce the ideas of equity and participation in the construction of knowledge is seen as responsible for the social and educational decline. A number of authors within FAES share and systematically support these types of discourse. They point out that comprehensive education is responsible for the systematic crisis in education in which Spain has been subsumed throughout the last two decades (Penalva Buitrago Citation2011). Using a common feature of the conservative way of thinking as is the demand for knowledge based on common sense, on experience versus theory and national versus foreign values (Vergara Citation2001), these groups object to the educational reforms implemented since the mid-1980s.

The obsession to achieve that all pupils learned the same forced the pedagogues behind the LOGSE to minimise the importance of contents in the curriculum and teacher training programmes, as well as to despise the indispensable values of learning such as merit, thoroughness and effort. (…) Left wing pedagogy, then, continues to be committed to lower expectations in terms of knowledge so everybody, with no effort, without thoroughness and discipline, is able to happily and comfortably achieve the minimum required. And, to do so, there is no need of teachers willing to learn more and teach more, but instead teachers up to their ears with pedagogic methodologies that have excessively proved to be ineffective in order to teach pupils (Delibes Citation2008, 2).

FAES’ documents criticise the intention of comprehensive education to offer a similar base of common learning regardless of existing social differences. These are faced with the need to offer a differentiated education according to the expectations and abilities of pupils. These authors suggest the possibility of segregating those students in the early stages of education who are incapable of keeping up with the rhythm of the classroom or are not interested in pursuing an academic path. Some texts suggest a reduction of the number of years assigned to compulsory education, situating its limit at the age of 12, and maintain that Spain should move towards “a more selective and differentiated system that fulfils the potentials of the children and the real needs of society” (Martínez López-Muñiz Citation2001, 333).

When defining the disposition of those students who are less interested or have less abilities with regard to schooling, the texts analysed here do not refer to any thoughts and ideas about the influence exerted by the pupils’ habitus or by spaces of socialisation, which have been previously demonstrated by other researchers (Martínez García Citation2007). On the contrary, the naturalisation of the social destinies of the students allows them to arrive at conclusions about the type of offer the education system should provide to certain groups:

Why should everybody get the same? Why are all of them necessarily together, the South American children that want to study and improve their lives with the ‘Latin King’ that are only interested in imposing their rabble? Is this what they call social cohesion? (Orrico Citation2005, 47)

Several texts reject explanations of the educational crisis that insist on the historical backwardness of Spanish education. Equally, the influence of social and economic variables is minimised. Therefore, the responsibility of the already mentioned educational decay is transferred to certain political actors, more concretely to the teachers and pupils. No reference is made to the uneven distribution of capitals throughout society, which is the basis of further dynamics of social reproduction.

Summing up, on this axis the decline of education is explained by the supposed abandonment of the contents, values and teaching methods that had historically proved their efficiency. On one hand, these authors denounce that “the transmission of knowledge, the instruction of citizens, and teaching in its more classic sense, continue to be treated as secondary matters in schools” (Delibes Citation2008, 3). On the other, they insist that “effort, perseverance, self-thoroughness and merit have gradually disappeared from the Spanish educational scene and have been replaced by coexistence, tolerance and solidarity. These have replaced the former set of values instead of being integrated within them in what has been called ‘education in moral standards’” (López Rupérez Citation2008). The proposal offered by all of FAES’ documents consists of a turnover in the normative ground and in terms of values or, in their own words, “a return to old standards” (Pericay Citation2005).

Advocating neoliberalism: The market as a fruitful source of solutions

The second axis in the discourse of FAES revolves around the opposition between public and private education, that is, between bureaucratic regulation and market mechanisms. The foundation advocates a stronger presence of private actors in the public arena and, simultaneously, the taking over of existing public schools by those same agents. The first of these processes corresponds to what Ball and Youdell (Citation2007, 9) call “exogenous privatisation”, referring to “forms or privatisation [that] involve the opening up of public education services to private sector participation on a for-profit basis and using the private sector to design, manage or deliver aspects of public education”. In line with this, FAES defends the potential growth of the presence of private interests as a curb on the pernicious consequences of comprehensive education and the abandonment of old educational traditions. As one of the texts suggests:

The private ownership of state-subsidised private schools and the competition among them to recruit students are measures that, little by little, have been implemented, which have mitigated the negative effects of the LOGSE. (…) In comparison with the public schools, their private counterparts, maybe given that the latter have been to recover the traditional values that left-wing thinkers deny, are cheaper to the public contributors and more attractive to a majority of people within society (Delibes Citation2005, 6–7).

Without offering references to any empirical evidence, it is theoretically argued that, given its own internal non-bureaucratic nature, the private sector is more flexible and adaptable to the development of processes of school improvement. Along these lines, López Rupérez suggests there is a need to introduce changes in the management of the public sector, abandoning traditional bureaucratic modes of government and replacing them with a mechanism to facilitate more autonomy and diversification from the side of education providers, higher levels of accountability and freedom of school choice for families:

[There is a need] to modernise the system of public funding of education based on the real cost per pupil, the attention to the demand, and the introduction of money follows the student models. (…) To promote the diversification of the offer, stimulating plurality, emulation and success across the system. This gives sense to the choices of the families and reduces processes of hierarchisation among the schools and the saturation of those that have a bigger demand (López Rupérez Citation2009, 17).

On one hand, FAES considers that the participation of families in the system should follow the logics of the law of supply and demand, where families should be understood as consumers and schools as providers of educational services. Education is seen as a private good based on the principle of competition (Lubienski Citation2001) and, therefore, parents should be given the right to make the individual choices they consider to better suit their children's needs (Chubb & Moe Citation1988). The responsibilities of the state in this new scenario are limited to a mere guarantor of the provision and funding of compulsory levels of elementary education. Given the benefits that higher degrees of education provide to individuals, the costs of such education should be transferred to them or, in our case, to their families:

Within non-compulsory levels, the current total or partial gratuity of public schools should be eventually erased and substituted by public aid to students (or their families in those cases where the children are still minor), which in most cases could take the form of credit loans with certain conditions (Martínez López-Muñiz 2001, 338).

On the other hand, from this perspective competition is the principle that should underpin the system. Several authors within the FAES network point out that even public schools would benefit from highly competitive environments given that in such contexts the whole set of actors is compelled to transform their educational processes in the right direction. As Enkvist (Citation2012) highlights, “there is evidence that the implementation of state-subsidised private schools forces the public sector to improve the quality of its offer in order not to lose all its students”. Moreover, schools should be able to select their students based on their academic performance even at basic and compulsory levels:

If students results were taken into account as the most important criteria in the scales that regulate the school choice scheme, wouldn't that promote effort and merit?, wouldn't that establish competition among schools and the pupils in order to improve?, isn't this an elementary principle in the entrepreneurial and exciting society that we aim to build? Measures such as the school voucher would fit in easily here (Ballester Citation2011, 158).

In addition to the above, it is suggested that public education adopts new forms of the management and provision of educational services. It is what Ball and Youdell identify as endogenous privatisation, which involves the “importing of ideas, techniques and practices from the private sector in order to make the public sector more businesses-like” (2007, 8–9). In this sense, FAES promotes diverse mechanisms of the externalisation of educational services and incentives to teachers and schools (for an analysis of these aspects see, for instance, Colectivo Lorenzo Luzuriaga Citation2008; author1 & author2 2010; Viñao Citation2012). They insist on the need to abandon traditional bureaucratic forms of governance, which should be replaced by new models of public management:

Models of bureaucratic management of public schools feature, inexorably, the deterioration of public schooling. For that reason, advances in this matter should be necessarily accompanied by a wider devolution of responsibilities to public schools and their management teams, and mechanisms of control and intervention based on accountability (López Rupérez Citation2009, 18).

There is evidence of the influence exerted by FAES and their ideas on the privatisation of the education system with varying degrees of implementation across different regions in Spain (author1 & author2 2010). Comparatively, at an international level Spain has one of the highest rates of private provision of education in Europe (author1 2012). According to Eurydice (Citation2009), Spain is the fourth country in the EU only behind the Netherlands, Belgium and Malta. Despite those figures, FAES continues to criticise the weakness of those processes and insists on the lack of adequate economic incentives and competition among suppliers. It also questions the size and role of the state, pointing out the need to reduce its presence in the education system.

In general terms, the discourse put forward by FAES is distributed through different formats and media and institutional spaces and refers to a normative crisis throughout the whole education system. According to its perspective, this crisis has its roots in the apparent loss of consensus and cultural unity within Occidental societies more generally, and in particular in Spain. As observed by other academics in different contexts (Apple Citation2001a; Ball Citation2003; Gleeson et al. Citation2001), the explanations of such a crisis and the consequent political alternatives are formed by elements that come from the foundation's two ideological sources: neoconservatism and neoliberalism. On one hand, FAES stresses the loss of a normative consensus on the aims and means of education among its own actors; on the other hand, it criticises the continuous pre-eminence and centrality of the role of the state in the organisation and operation of the education system to the detriment of market mechanisms.

Final remarks … or conclusions ‘in progress’

Education policy is changing rapidly and, in order to be able to grasp the depth and implications of such transformation, new concepts, theoretical perspectives and research methods are needed. As Sorensen and Torfing (Citation2007, 3) suggest, “it is clear that policy making and public governance is no longer congruent with the formal political institutions in terms of parliament and public administration”. Our research is concerned with the new ways in which neoliberal solutions are introduced within spaces that, not long ago, were the domain of social-democratic formulas and the welfare state. In doing so, we share the claim of Jessop and his colleagues for “a more systematic recognition of polymorphy – the organization of sociospatial relations in multiple forms and dimensions – in sociospatial theory” (Jessop et al. 2007, 390).

This paper is still a ‘work in progress’ and therefore robust and final conclusions cannot be drawn at this stage. However, in this article we have shown how a set of new actors and institutional relations, synthesised in what we have called here the network, are organised within new structures and have operationalised discourses through which neoliberal ideas and policies are canalised and transformed into ‘common sense’. Analysing the discursive strategies, connections, activities, agendas, texts etc. of these intermediary actors is a key task in order to unravel the processes of what could be called ‘doing’ neoliberalism. This implies focussing on “how ‘local’ institutional forms of neoliberalism relate to its more general (ideological) character” (Peck & Tickell Citation2002, 381). The cases analysed in this paper are relevant as they help us understand how neoliberalism ‘gets done’. These think tanks, foundations and other neoliberal organisations are located at a meso-level, taking advantage of and operating through what Jessop (Citation2002, 229) describes as the “fuzziness of institutional boundaries”.

It is within this opaque and nebulous configuration of new and old actors, ambiguous responsibilities and blurry margins of action that contemporary educational policy research struggles to offer creative and alternative explanations. This task is significantly complex, some would even consider it as unapproachable, yet for us it represents a challenging opportunity to dive in and uncover the new shapes and configurations whereby the old dynamics of social exclusion and segregation are translated into our present time.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their incisive comments and valuable suggestions to improve this paper.

Notes

Antonio Olmedo is a British Academy Newton International Fellow based at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Institute of Education, University of London, United Kingdom. His research interests and publications rest within the field of Education Policy Analisys and Sociology of Education, more concretely in the relation between Education Policy and social class: social inequalities and segregation; neoliberal policies and the creation of quasi-markets; and global networks, international organisations, policy advocacy, philanthropy, and ‘edu-businesses’: international education policy and emerging patterns of access, opportunity and achievement in education. Email: [email protected]

Eduardo Santa Cruz Grau is a Chilean sociologist and researcher at the University of Granada, Spain. He is currently finishing his PhD. He is also a researcher at the Interdisciplinary Research Programme in Education (PIIE) and the Research Centre in Education in the University UCIFN, both in Chile. He has published several articles and contributions to books in the field of sociology of education, education policy, education reform, media and citizenship. Email: [email protected]

1 1. Microsoft Access and NodeXL (an open source template for Microsoft Excel) were used to create the databases where all the information was stored and the network diagrams were generated.

2 2. In this case the documents, transcriptions and materials were analysed using the qualitative data analysis software QSR NVivo 10.

5 5. Due to space limitations, this paper focuses on the network of connections, advocacy strategies and political discourse of FAES. Already ongoing research and further publications will focus on the influence and impact of the foundation's activities on the implementation and enactment of political legislation.

6 6. Campus FAES is also annually replicated in a number of Latin American countries (Argentina, Chile, Colombia and Peru) as well as in Central America & the Caribbean.

7 7. The full presentation can be found at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v =fS2O7OLnsYk&feature=youtube

8 8. Francisco López Rupérez has held, among others, the positions of Director General of Education and Culture (1996–1998) and Secretary General of Education and Training (1998–1999) the Ministry of Education; Deputy Minister of Education of the Community of Madrid (2000); and Minister of Education in the Permanent Delegations of Spain to the OECD, UNESCO and the Council of Europe (2000–2004). See http://www.mecd.gob.es/ministerio-mecd/organizacion/organismos/presidente-consejo-escolar-estado.html

14 14. http://atlasnetwork.org

15 15. For a complete list of the FAES network in the USA, see: http://www.fundacionfaes.org/en/red_de_think_tanks_en_estados_unidos

16 16. For a complete list of the FAES network in Europe, see: http://www.fundacionfaes.org/en/european_ideas_network_y_red_europea_de_fundaciones

Bibliography

- Anderson B. Comunidades imaginadas. 1993; México D. F.: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

- Apple M.W. Comparing Neo-liberal Projects and Inequality in Education. Comparative Education. 2001a; 37(4): 409–423.

- Apple M.W. Educating the ‘right’ way: Markets, standards, God, and inequality. 2001b; New York: RoutledgeFalmer.

- Ball S.J. The teacher's soul and the terrors of performativity. Journal of Education Policy. 2003; 18(2): 215–228.

- Ball S.J. Education Plc: Understanding private sector participation in public sector education. 2007; London: Routledge.

- Ball S.J. Privatising Education, Privatising Education Policy, Privatising Educational Research: Network Governance and the ‘Competition State’. Journal of Education Policy. 2009; 24(1): 83–99.

- Ball S.J, Junemann C. Networks, new governance and education. 2012; Bristol: Policy Press.

- Ball S.J, Olmedo A. Global Social Capitalism: Using Enterprise to Solve the Problems of the World. Citizenship, Social and Economics Education. 2012; 10(2&3): 83–90.

- Ball S.J, Youdell D. Hidden privatisation in public education. 2007. http://www.ei-ie.org/annualreport2007/upload/content_trsl_images/613/Hidden_privatisation-EN.pdf (Accessed 2013-03-14).

- Ballester M. Bases ideológicas del sistema educativo español. Cuadernos de Pensamiento Político. 2011; 31

- Bernal J.L. Parental Choice, Social Class and Market Forces: The Consequences of Privatization of Public Services in Education. Journal of Education Policy. 2005; 20(6): 799–792.

- Bolívar A. La educación no es un mercado. Crítica de la “Gestión de Calidad Total”. Aula de Innovación eEducativa. 1999; 83–84: 77–82.

- Bonal X. Curriculum Change as a Form of Educational Policy Legitimation: The Case of Spain. International Studies in Sociology of Education. 1995; 5(2): 203–220.

- Bonal X. Interest groups and the State in contemporary Spanish education policy. Journal of Education Policy. 2000; 15(2): 201–216.

- Calero J. Una Evaluación de los Cuasimercados como Instrumento de Mejora para la Reforma del Sector Público. 1998; Bilbao: Fundación BBV.

- Calero J, Bonal X. Política Educativa y Gasto Público en Educación. 1999; Barcelona: Ediciones Pomares-Corredor.

- Cerni P. Paradoxes of the Competition State: The Dynamics of Political Globalization. Government and Opposition. 1997; 32(2): 251–274.

- Chubb J.E, Moe T.M. Politics, Markets, and the Organization of Schools. The American Political Science Review. 1988; 82(4): 1065–1087.

- Colectivo Lorenzo Luzuriaga. Análisis de la educación en la comunidad de Madrid. 2008. http://www.colectivolorenzoluzuriaga.com/PDF/Por_la_Esc_Pub_y_analisis_Com_Madrid_19_may_08.pdf (Accessed 2013-03-14).

- Delibes A. En Nombre de la equidad no se puede extender la ignorancia. Papeles FAES. 2005 21 http://www.fundacionfaes.org/es/documentos/show/00031-00 (Accessed 2013-03-14).

- Delibes A. Cuatro años de retroceso en la educación española. Papeles FAES. 2008 66 http://www.fundacionfaes.org/es/documentos/show/000554 (Accessed 2013-03-14).

- Dicken P, Kelly P.F, Olds K, Wai-Chung Yeung H. Chains and Networks, Territories and Scales: Towards a Relational Framework for Analysing the Global Economy. Global Networks. 2001; 1(2): 89–112.

- Edwards G. Mixed-method approaches to social network analysis. 2010. Discussion Paper. National Centre for Research Methods. ESRC. http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/842/ (Accessed 2013-03-14).

- Enkvist I. Suecia deja atrás los experimentos pedagógicos progresistas. Cuadernos de Pensamiento Político. 2012; 35 http://www.fundacionfaes.org/record_file/filename/3462/063-074_0Inger_Enkvist.pdf (Accessed 2013-03-14).

- Eurydice. Key data on education in Europe 2009. 2009; Brussels: Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency.

- Fairclough N. Analysing discourse. 2003; London: Routledge.

- Fairclough N. El análisis crítico del discurso y la mercantilización del discurso público: Las universidades. Discurso & Sociedad. 2008; 2(1): 170–185. [PubMedAbstract] [PubMedCentralFullText].

- Fairclough N, Graham P, Lemke J, Wodak R. Introduction. Critical Discourse Studies. 2004; 1(1): 1–7.

- Fairclough N, Wodak R, Van Dijk T. A. Critical discourse analysis. Discourse Studies. A Multidisciplinary Introduction. Vol. 2. Discourse as Interaction. 1997; London: Sage. 258–284.

- Foucault M. The archaeology of knowledge. 1972; London: Tavistock Publications.

- Foucault M. Governmentality. Ideology and Consciousness. 1979; 6: 5–21.

- Gale T. Critical Policy Sociology: Historiography, Archaeology and Genealogy as Methods of Policy Analysis. Journal of Education Policy. 2001; 16(5): 379–393.

- Gleeson D, Husbands C, Whitty G, Ball S.J. The performing school: Managing, teaching and learning in a performance culture. 2001; London: RoutledgeFalmer.

- González J.L. ¿Educación para la Ciudadanía o atentado a la democracia?. Cuadernos de Pensamiento Político. 2008. http://www.fundacionfaes.org/record_file/filename/2217/265-284_JL_GONZALEZ.pdf (Accessed 2013-03-14).

- Howard P.N. Network Ethnography and the Hypermedia Organization: New Media, New Organizations, New Methods. New Media Society. 2002; 4(4): 550–574.

- Jessop B. The future of the capitalist state. 2002; Cambridge: Polity.

- Keck M, Sikkink K. Activists beyond borders: Advocacy networks in international politics. 1998; Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- López Rupérez F. Una educación para ganar el futuro. Papeles FAES. 2008; 64 http://www.fundacionfaes.org/record_file/filename/1611/papeles64.pdf (Accessed 2013-03-14).

- López Rupérez F. La reforma de la educación escolar. Ideas para salir a la crisis. 2009; 2 http://www.fundacionfaes.org/record_file/filename/2587/CRISIS_02C.pdf (Accessed 2013-03-14).

- Lubienski C. Institutionalist and Instrumentalist Perspectives on “Public” Education: Strategies and Implications of the School Choice Movement in Michigan. Occasional Paper No. 39. 2001; National Center for the Study of Privatization in Education, Teachers College, Columbia University.

- Martínez García J. Fracaso escolar, clase social y política educativa. Viejo Topo. 2007; 238: 44–49.

- Martínez López-Muñiz J.L. Ejes para una reforma El sistema educativo en la España de los 2000. 2001; Madrid: Fundación para el Análisis y los Estudios Sociales.

- Mato D, Grimson A. Think tanks, fundaciones y profesionales en la promoción de ideas (neo)liberales en América Latina. Cultura y neoliberalismo. 1997; Buenos Aires: CLACSO. 19–42.

- McCann E. Urban Policy Mobilities and Global Circuits of Knowledge: Toward a Research Agenda. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 2011; 101(1): 107–130.

- Miller P, Rose N.S. Governing the present. 2008; Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Nasarre E. La gran ruptura de la educación en Europa. Cuadernos de Pensamiento Político. 2010; 27: 145–163.

- Olmedo A. De la participación democrática a la elección de centro: las bases del cuasimercado español en la legislación educativa española, Education Policy Analysis Archives. Archivos Analíticos de Políticas Educativas. 2008; 16(21): 1–35.

- Olmedo A. Policy Makers, Market Advocates and Edu-Businesses: New and Renewed Players in the Spanish Education Policy Arena. Journal of Education Policy. 2013; 28(1): 55–76.

- Orrico J. La ruina de la enseñanza española. Cuadernos de Pensamiento Político. 2005; 8: 27–55.

- Ozga J, Jones R. Travelling and Embedded Policy: The Case of Knowledge Transfer. Journal of Education Policy. 2006; 21(1): 1–17.

- Peck J, Tickell A. Neoliberalizing Space. Antipode. 2002; 34(3): 380–404.

- Penalva Buitrago J. El paradigma LOGSE: Un error intelectual. Cuadernos de Pensamiento Político. 2011; 30: 117–150.

- Pericay X. ‘Buenismo’ y sistema educativo. Cuadernos de Pensamiento Político. 2005; 8: 57–68.

- Rodríguez M.d.M. La Metamorfosis del Cambio Educativo. 2003; Madrid: Ediciones Akal.

- Sainz J, Sanz I, Sanz J. El informe PISA 2009. España empeora sus resultados. Papeles FAES. 2011; 153 http://www.fundacionfaes.org/record_file/filename/3001/papel_153.pdf (Accessed 2013-03-14).

- Sheppard E. The Spaces and Times of Globalization: Place, Scale, Networks, and Positionality. Economic Geography. 2002; 78(3): 307–330.

- Sørensen E, Torfing J, Sørensen E, Torfing J. Governance network research: Towards a second generation. Theories of Democratic Network Governance. 2007; Basingstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan. 1–21.

- Thomas S. Contesting Education Policy in the Public Sphere: Media Debates over Policies for the Queensland School Curriculum. Journal Education Policy. 2002; 17(2): 187–198.

- Urry J. Social Networks, Travel and Talk. The British Journal of Sociology. 2003; 54(2): 155–175.

- Vergara J. Teorías conservadoras y teorías críticas de las instituciones sociales. Revista de Ciencias Sociales. 2001; 11: 138–157.

- Vermoet Á Regreso a la ignorancia. Papeles FAES. 2007; 43 http://www.fundacionfaes.org/record_file/filename/503/00075-00_-_regreso_a_la_ignorancia.pdf (Accessed 2013-03-14).

- Verón E. El cuerpo de las imágenes. 2001; Colombia: Editorial Norma.

- Viñao A. El desmantelamiento del derecho a la educación: Discursos y estrategias neoconservadoras. AREAS, Revista Internacional de Ciencias Sociales. 2012; 31: 97–107.

- Wodak R, Wodak R, Meyer M. The discourse-historical approach. Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis. 2003; London: SAGE. 64–94.