Abstract

The study aims to generate new knowledge regarding how subject teachers in children's and young people's education conceive of the didactic relationship between their own subject knowledge and the computer's infinite possibilities concerning information and knowledge.

The theoretic frames of the study lie within modern phenomenology with special inspiration from the concept of the life-world. This applies to both the relationship among subject knowledge, technology and human beings, and the theory of science and methodological instrumentation and analysis.

The empirical turn of the life-world phenomenology makes it possible to collect data through research interviews. The study comprises 41 teachers in five different schools who have worked in One-to-One environments for varying lengths of time, between 24 and 36 months.

The analysis of the interviews shows that the teachers perceive and distinguish 11 different qualities compiled in three main categories where they describe the didactic relationship between their own subject knowledge and the computer's infinite potential concerning information and knowledge.

Introduction

Ever since classical antiquity, teaching competence has been constituted via three main components. The first consists of the area connected to subject knowledge – few people think that skilled teachers can be completely without subject knowledge. It is more the case that deep and broad knowledge of the subject(s) one teaches leads to safety and security in the teaching situation, while parallel to that there are greater opportunities for improvisation and pupil-active methods for learning are possible. A teacher who knows what s/he is doing can indulge in digressions in teaching methodology and innovative experiments. These teachers are generally also more responsive to changes in their profession.

Research shows that the second component of teaching competence is the pedagogical or didactic skill to make somebody else want to learn something. The focus is then placed on methodological skills. Pedagogy and didactics are academic disciplines but are seldom mentioned as such in the research or debate about teaching competence. They instead function as attributes of the actions performed by teachers.

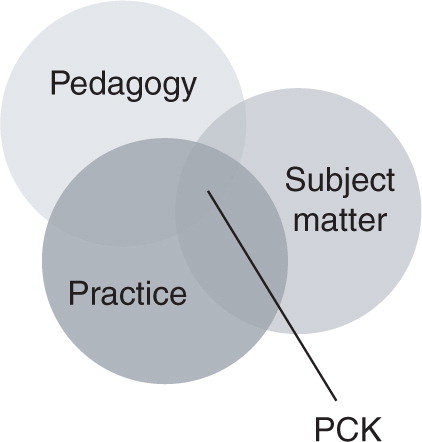

The third component of teaching competence is described by Lee Shulman (Citation1986) among others as insights into the context or practice in which the teacher works. Schools are different and contexts differ as well, which explains why the pupils’ life-world is also decisive for the ability to choose contents and methods in teaching. Shulman's description of the professional composition may be captured in (cf. Shulman, Citation1986). He assumes that the joint sectional area where all circles overlap constitutes the specific content of the unique PCK (Pedagogical Content Knowledge). This implies that Shulman argues that the prerequisites of the context or pedagogical practice direct the view of the subject theory and pedagogy, which must then be adapted and subordinated to the practice. Similar theories are also found, for example, in Marton, Runesson and Tsui (2004), Wolfgang Klafki (Citation1993) and Paul Hirst (Citation1971).

Figure 1. The Shulman model of teacher knowledge in which PCK is presented as a unique knowledge domain.

Research that pays attention to the practical (socio-cultural) context is emphasised by e.g. Vygotskij (Citation1978), Wertsch (Citation1998), Rogoff and Wenger (Citation1984), and Lave and Wenger (Citation1990) in their respective theories of situated learning. The consequence of these theories in our present case implies that a One-to-One project in education changes a local practice, which in turn influences the teachers’ conceptions and view of both the subject theory and the pedagogy. What then becomes important to study is what this means from the point of view of content for teachers’ conceptions of teaching competence in digital times. Angeli and Valanides develop Shulman's PCK by adding technology to subject theory, pedagogy and practice:

[…] concluding that TPCK is a unique body of knowledge that is constructed from the interaction of its individual contributing knowledge bases. Then, ICT–TPCK is introduced as a strand of TPCK, and is described as the ways knowledge about tools and their affordances, pedagogy, content, learners, and context are synthesized into an understanding of how particular topics that are difficult to be understood by learners or difficult to be represented by teachers can be transformed and taught more effectively with technology in ways that signify its added value (Angeli and Valanides 2008, 154).

The subject theoretical emphasis is most often discussed by pure subject representatives, where teaching competence becomes a matter of knowing and understanding how knowledge is structured, the theories, principles and paradigmatic turns of the discipline or subject (cf. Davis and Simmt Citation2006; De Nobile Citation2007; Spear-Swerling, Brucker and Alfano Citation2005). The emphasis on the teachers’ subject theoretical knowledge, as a prerequisite for the profession, is noticeable when it comes to recruiting students with disciplinary skills to the teaching profession and making those teachers with disciplinary skills stay in the profession. In e.g. the article Who Will Teach?, Richard Murnane et al. (Citation1991) say, “College graduates with high test scores are less likely to take [teaching] jobs, employed teachers with high test scores are less likely to stay, and former teachers with high test scores are less likely to return”. A further factor brought forth in the discussion of teachers’ subject competence is the emphasis on the relationship between teachers’ good subject theoretical knowledge and pupils’ results at knowledge tests. It is difficult to find evidence in support of this thesis in the research.

Deepened subject knowledge is relatively emphasised by the governments of different countries, in particular when the quality of education is to be improved. The Swedish Government notes:

The older the pupils are and the farther the pupils have come in their knowledge development, the greater is the need for teachers with deepened subject knowledge. In order to be able to meet these demands, the Government judges that teachers in lower secondary and upper secondary schools should be given a more specialised and deeper subject competence in comparison with the primary school teachers (Prop. Citation2009/10:89, 24).

Large funds are spent based on the thesis that teachers’ subject knowledge is the best guarantee of pupils acquiring advanced knowledge qualities. The connection between good subject knowledge and the proficient teacher is a clear political assumption, as is the idea that the teacher's solely foremost professional identity is linked to the qualities of the subject knowledge of the individual professional practitioner. The subject teachers’ trade organisation also shares this point of view at the same time as it is reported to be common among subject teachers themselves. This has been the case in e.g. Sweden for a long time.

Our point of departure in this study is exactly the superordinate position of subject theory as the basis of teaching competence, where we want to study what happens from the teachers’ own perspective to precisely this part of the competence when it is challenged in the classroom by a highly competent knowledge artefact – namely, the computer (personal computer, iPad, smartphone etc.) in the One-to-One project.

Aim

The study aims to generate new knowledge of how subject teachers in children's and young people's education conceive of the didactic relationship between their own subject knowledge and the computer's infinite possibilities concerning information and knowledge.

The questions we analysed are:

1. What is subject knowledge for schoolteachers from a subject teacher perspective?

2. What is digital knowledge in education from a subject teacher perspective?

3. What is the relationship between subject knowledge and digital knowledge from a subject teacher perspective?

Previous research – a knowledge overview

Terminologically, we distinguish teachers’ subject knowledge from what we now call digital knowledge. The distinction means that subject knowledge is something possessed by the individual teacher, it is an effect of teacher education or in-service training courses. Teachers’ subject knowledge is personal and professional in the sense that the knowledge may be possessed by an individual teacher in the context of a profession that defines collective demands on what is important knowledge. On the other hand, digital knowledge is characterised by the opposite. It is global and infinite in that it is supported and controlled by the incredible diversity that externally characterises the Internet. Such knowledge can be communicated in real-time by a very large number of people and is not limited to the teacher who is in that particular classroom.

In other contexts, terms like Digital Technologies, ICT skills, technology skills, information technology skills, 21st century skills, information literacy, digital literacy and digital skills are used to describe the complex relationships between information, knowledge and technology (Laksala 2011). We have chosen the term digital knowledge as a clear counterpart to the long-standing use of the term subject knowledge of teachers.

We have been unable to find any study on the relationship between teachers’ analogue subject knowledge and digital subject knowledge within the framework of One-to-One projects in schools. However, there are research results that pay attention to variants of our research focus. Papert (Citation1997), Fucs and Woessmann (Citation2004), and Wong and Li (Citation2006) showed that the computer can be an effective tool for teachers to use when it comes to attaining different educational goals in education and that teachers are in need of a higher degree of ICT-related knowledge. Becker and Anderson (1998) discuss the question of whether it can be at all possible for computers in schools to change the teachers’ teaching and the pupils’ learning processes. Cuban (Citation2000; Citation2001) shows in several studies that the teachers’ role changes when new technology is established in education but that it can never replace the teacher's subject competence. The reason stated is that the classes in schools are generally too big, for which reason the teacher does not have time for everybody, and that the teachers have many subjects to teach, making it difficult to handle the computer in every subject. He further argues that computers are difficult to handle and often break down. Becker and Raviz oppose this view:

Yet, although Cuban's argument may have applied in the mid-1980's, is it correct today? The capabilities and functionality of what we call personal computers have changed by orders of magnitude since Cuban first wrote about desktop microcomputer technology. What passed for classroom computers fifteen years ago seem like primitive toys today (Becker and Raviz Citation2001, 2).

In addition, they conclude, “[…] the most professionally active teachers, in a position to provide leadership with their teacher peers, are the most active computer users of all” (Becker and Raviz Citation2001, 14). Hayat Al-Khatib (Citation2012) argues that the computer in the classroom enforces a new pedagogy where the pupil must be allowed to be more active:

The full potential of ICT support should be explored in learner-centred strategies to shift pedagogic orientation to cater more for the role of the learner in the learning process, taking advantage of the resources and tools made available in the digital age (Al-Khatib Citation2012).

Similar conclusions are drawn by Pečiuliauskiene and Barkauskaite (Citation2007) when they state that, if teachers are to develop their pedagogical skills in connection with the use of computers in education, they must acquire knowledge of how the computer functions as a pedagogical tool: “it has been found out that successful ICT application in educational practice is determined by basic ICT competencies” (Pečiuliauskiene and Barkauskaite 2008, 407). Hennesey, Ruthven and Brindely (Citation2005) argue: “teachers were developing and trialling new strategies specifically for mediating ICT-supported learning. In particular, these overcame the potentially obstructive role of some forms of ICT by focusing pupils’ attention onto underlying learning objectives”. Kleiger, Ben-Hur and Bar-Yossef (Citation2010) show that teachers see subject-matter training as the most relevant component for developing ICT competencies and, in addition, they prefer face-to-face meetings in their schools. In a study reported in 2007, Dunleavy, Dextert and Heinecket concluded:

In order to create effective learning environments, teachers need opportunities to learn what instruction and assessment practices, curricular resources and classroom management skills work best in a 1:1 student to networked laptop classroom setting (Dunleavy, Dextert and Heinecket Citation2007, 440).

Säljö adds an important conclusion when he notes that:

Mindwares do not think for themselves, even a complex mind werewolf is still a mind were. But when such resources are integrated into most of what we do, and when they reach a level of complexity in which they process and analyse information relevant to social action, then our mastery of such tools is a critical element of what we know (Säljö Citation2010, 53–64).

In an extensive study, Condie and Munro (Citation2007) point out that teachers in pre- and in-service programmes need more targeted education when it comes to subject knowledge in the context of One-to-One in the school. They claim:

Recent research suggests that student teachers’ understanding of the pedagogy of teaching with ICT develops in stages which correlate closely to their developing understanding of the pedagogy of their subject, and that this level of sophisticated thinking generally matures late in their training (Condie and Munro Citation2007, 18).

… Teachers were looking for staff development beyond managing the technology and, increasingly, for guidance and advice in embedding ICT in everyday practice, particularly in relation to specific subject areas (Condie and Munro Citation2007, 19).

Taken together, the research describes a complex and differentiated picture of how teachers’ subject competence relates to the information and knowledge that digital artefacts can offer in education. In principle, the research results have changed from being relatively doubtful and negative regarding digital technology in the 1990s and early 21st century in comparison to what a teacher proficient in their subject can achieve – to adopting a more complex and composite description in the last few years. The computer can be an aid for teachers provided that they are given training in digital handling and develop deeper subject knowledge, they change their pedagogical strategies and take the child's/pupil's preconditions into account to a greater extent.

Theory and method

The basic assumptions of the study lie within phenomenology and find special inspiration from Heidegger (Citation1927) and Merleau-Ponty (Citation1962) along with Don Ihde's post-phenomenological standpoint (Ihde Citation2009; Citation2010; Citation2010b). This applies to both the relationship among subject knowledge, technology and human beings, and to the theory of science and methodological instrumentation and analysis.

The digitalisation of education means that information and knowledge have become available in a different way than before. The education that is now developing in a large part of the world is not like that which most of us have an experience of. Everything is now much faster, the availability is almost total as regards information and knowledge, and people are also constantly accessible. To all appearances, the computer is technically one of humanity's foremost innovations. But new technology does not in itself create new preconditions since it is in the interaction between technology and human beings that changes take place. Ontologically, this assumption implies that the essence of digital technology is not technological but existential (cf. Ihde Citation2010).

Thus therefore means that technology does not change human beings’ conditions one-sidedly, no more than human beings change technology one-sidedly – it is a mutual process in which human beings change at the same time as technology changes and vice versa. Merleau-Ponty (Citation1962) argues, “there is no inner man, man is in the world, and only in the world does he know himself”. Correspondingly, computers in education do not change the teachers’ subject competence one-sidedly. Nor does the teachers’ competence affect the computers’ potential. It is an existential situation where both parties influence each other simultaneously.

In the past, human beings assumed a submissive attitude to nature where it dictated human beings’ possibilities. Later on, this position changed and human beings made themselves the master of nature. On the contrary, digital technology sees human beings and technology as dependent on each other. Heidegger speaks in terms of technology having made the world a standing-reserve (Bestand) (1977, 296) and man an orderer who opens, transforms, distributes, stores etc. what we take out of the world.

Precisely because man is challenged more originally than are the energies of nature, i.e., into the process of ordering, he never is transformed into mere standing-reserve. Science man drives technology toward, he takes part in ordering as a way of revealing (Heidegger Citation1977, 299–300).

According to this, man is placed (Gestell) in a world of possibilities as an orderer, where technology shows itself as something that gives us answers to questions we ask. The technology in itself does not formulate any questions, however. Ihde (Citation2010) interprets Heidegger in this way:

[…] if the world is viewed as standing-reserve, the basic way in which the world is experienced, there must also be a correlated human response. That, too, takes particular shape in a technological epoch (Ihde Citation2010, 34).

Heidegger's own formulation is: “The earth now reveals itself as a coal mining district, the soil as a mineral deposit” (Heidegger Citation1977, 296). Taken together, the consequence is that the computer in education is existential in the first place in the sense that it only functions in relation to the teacher and the pupil – and that it opens up for possibilities that are innovative, creative and new.

The subject teacher's relation to the information and knowledge that are accessible via digital resources is understood here to mean that the teacher can see herself/himself as an important and creative part of the technology that the computer brings into education. Technology incarnated in the form of One-to-One in education does not lead its own life; it is instead a standing reserve that is existentially linked to the teacher as a professional and as a human being and always placed in the possibility.

By this we want to emphasise that our theoretical point of departure as regards the subject teacher's relation to the digital technology is framed more by professional possibilities than by the idea that the technology in itself should dictate the conditions for teachers’ work in the practice of schools.

The overarching aim of the study is to investigate how teachers in children's and young people's education conceive of their own subject competence in relation to the possibilities the computer offers pupils in One-to-One schools. Since it is an experience and conception study – where data are dealt with qualitatively – we chose phenomenology as the basis of the theory and method. Edmund Husserl has discussed all of these parts, but we take our most distinct point of departure in Merleau-Ponty's and Heidegger's development of these concepts.

We all live in the same world but in different realities and it is in our conceptions that the world presents itself to us precisely as distinguishing qualities. This implies that when we experience something it always appears holistically, but we distinguish only one aspect of this whole at a time. This distinction is individual and is described as a quality or as a phenomenon (that which shows itself).

Phenomenologically, perception is not passive but active; holistically, it is bodily interactive with an environment […] it is the phenomenologically derived variation that provides the rigorous demonstration (Ihde Citation2009, 15).

The goal of the analysis is to find variations in how an object may be experienced as a phenomenon where the descriptive level of the result is presented in qualitatively different categories. In this study, phenomenology is used in order to find, describe and understand how subject teachers in qualitatively different ways experience and conceive of the didactic relationship between their own subject knowledge and the computer's infinite potential for information and knowledge.

The assumption of the embodiment comprises not only the physical body, that we are more than merely our cognitive perceptions, but it also includes the material world as well as its cultural and social dimensions. It is in our embodiment that we make ourselves exposed and present for other people and for ourselves. Likewise, it is our embodiment that makes us unique. The rigorous use of the phenomenology, as we understand it here, includes the assumption that we use all of the computer's possibilities via a bodily presence via the computer's keyboard or screen. We press the keys, move our fingers on the screen and we see and hear in a way that makes us part of the computer itself, which becomes part of ourselves.

What counts for the orientation of the spectacle is not my body as it in fact is, as a thing in objective space, but a system of possible actions, a virtual body with its phenomenal ‘place’ defined by its task and situation. My body is wherever there is something to be done (Merleau-Ponty Citation1962, 250).

The computer is incorporated in ourselves when we use it. The keyboard and the screen become an extension of our bodies in an intentional act. This description shows Heidegger's exposition of how different tools or artefacts become a part of ourselves. The computer in education is merely an object for the teachers when they do not use it in the classroom. At the moment the computer is put to use, it is included in a context that is not limited by the physical computer or the room it is in. The embodied intentional act can take the teacher and the pupil far outside and beyond what is visible or audible; it is the computer's communicability in cyberspace that becomes the teacher's embodied experience. It is mediated via a unique technology out into a seemingly infinite world. The analysis of data we undertook takes into consideration not only cognitive aspects of the teachers’ opinions of how subject teachers in children's and young people's education conceive of the didactic relationship between their own subject knowledge and the computer's infinite potential for information and knowledge, but also a more composite and complex point of departure.

We also want to understand the computer in education in a meaningful context. It is there as a tool that precisely refers to schoolwork, where the acquisition of information and knowledge is included. It also refers to certain attributes of a knowledge concept as well as to forms of learning: education acts, curricula, goal fulfilments, judgement, marking but also in a more general sense to words and letters, reading ability, digital competence etc. Teachers’ subject knowledge just as the computer in a One-to-One project cannot be placed outside its context in a study such as this one.

The life-world, as we understand it here, is placed within the phenomenology Heidegger (Citation1927) represents but which has also been developed, among others, by Merleau-Ponty (Citation1962), van Manen (Citation1990; Citation1991), Bengtsson (Citation2000) and Ihde (Citation2010b). The life-world is concrete and lived, which implies that the practical everyday school context or teachers’ subject knowledge can only be understood and described as qualitative, composite, contradictory, muddled, historical and complex. The life-world is carried collectively but experienced individually – subjectively handled and experienced. This implies that we see the world as experienced and that these perceptions can only be taken seriously if they are given composite and complex preconditions in data collection and the analysis. Various researchers (e.g. van Manen Citation1990) have chosen descriptive levels other than those employed by us (narration among other things) when presenting results based on the life-world. We choose here the descriptive category as the level of the research account.

Method and implementation

The empirical turn of life-world phenomenology enables us to collect data through research interviews (Kvale Citation1983, Citation1994). This is made possible by means of Husserl's concept of intentionality (in Ideas; Cartesian Meditations), where consciousness is described in terms of always being directed at something; when we experience or perceive something it is always something we experience or perceive. These perceptions are mediated as language in a research interview. For this reason, we conducted research interviews with subject teachers where we interpret, describe and categorise what they say they perceive of the didactic relationship between their own subject knowledge and the computer's infinite potential for information and knowledge.

The study comprises 41 teachers in five different schools who have worked in One-to-One environments for varying lengths of time, between 24 and 36 months. The selection of interviewed teachers was made by the headmaster of the respective school, where the only demand for participation was that they are subject teachers and that they have experience of having worked for at least one year in One-to-One environments in the schools. The interviews are thematically organised with consistently entirely open questions. The interviews were recorded on MP3 players and transcribed verbatim without any omissions. The interviews lasted between 25 and 45 minutes and the transcribed material consists of a total of 657 pages of text. The analysis is based on qualitative differences within the same content. These qualitative differences are then defined in terms of categories. The criterion for a category is that each of these should contently exclude other content. The categories are not hierarchically ordered but logically connected.

The analysis of the transcriptions was performed as close to the statement level as possible, which means interpretation close to the text that is “on the line” (cf. Kroksmark Citation1987; Citation2007). The interpretation includes the precondition that we cannot study statements one-sidedly or by themselves; they are always included in an existential meeting with the person who interprets and analyses. Here we used the parenthesis-setting method (epoché, cf. Barbosa da Silva Citation1996, 36–40) in such a way that as much as possible we tried to disregard our own prejudices or pre-understandings of the content. The analysis was made by means of a classical hermeneutic pendulation between the whole and the parts – the parts and the whole out of which the qualitative differences in content are extracted, ordered and classified. The transcriptions were read time and again where the interpretation and result went through two different steps. The first is individual where each of us made her/his own interpretation, after which this was tested against the research group's combined analysis and result (inter-judge reliability). The concrete analysis was performed so that the overall pendulation within the different parts of the transcriptions led to a large number of statements identified that contained relevant avowals. Out of the avowals or statements, meaning condensation was generated, which means that a new level of content qualities was condensed. This condensation and focusing is designed to make data clearer and cleaner. From this process, we developed a number of sub-categories that qualify and define the qualities of the data. In the final analysis, we abstracted the final category system that is an abstraction and minimisation of the number of subcategories. The analysis and the result are thus individual and collective work implemented by all participants to the same degree.

Result

The analysis of the interviews shows that the teachers perceive and distinguish 11 different qualities compiled in three main categories where they describe the didactic relationship between their own subject knowledge and the computer's infinite potential regarding information and knowledge:

1. The computer provides support in the teaching

- Concretisation and swiftness

- Individualisation

- Factual knowledge

- Presentations and syntheses

- Communication

2. The computer in education makes no difference

- Learning through teaching

- The teacher as the chief resource

- The computer as a substitute for weak subject knowledge

- Knowledge ambivalence in the subject teaching

3. The computer in education is changing the subject knowledge

- Internet knowledge before subject knowledge

- The computer requires broader and deeper subject knowledge

Category 1

The computer provides support in the teaching

The category is broadly constituted and contains five different dimensions, where the teachers state that they perceive that the computer supports the teaching and learning themselves. The subcategories within the main category are concretisation and swiftness, individualisation, factual knowledge, presentation and syntheses and communication.

Concretisation and swiftness

This subcategory identifies the computer as a supportive resource for both the teacher and the pupils in the teaching and learning situation itself. The possibility to concretise in combination with the computer's swiftness complements the teacher's own subject knowledge, and often when unexpected questions are asked by the pupils this does not lead to an organisational problem in the classroom since the computer via the Internet can quickly find the information.

By this I mean, if you talk of for example evolution, it is of course Charles Darwin. So it's only one push away and they'll get all the information. I don't have to stand rattling off facts but can instead focus on other content. I can help them with analyses and reflections instead … (Teacher no. 5).

Individualisation

Individual work has been given ever larger scope in education. A clear trend in Swedish schools is that the pupils are given opportunities to take greater responsibility for their learning – this applies to both planning and the implementation itself. The learning is then regarded as an individual project.

In the subcategory, the teachers describe that the individualisation work is easier with the aid of the computer. No distinction is made here between positive and negative individualisation. In the former type of individualisation, the content is adapted to the pupil's knowledge and abstraction level. The pupil automatically chooses the level that s/he understands best of all.

It's easier for me to individualise since everybody sits with her/his work on the computer. There is not this nagging in the classroom about help. Instead, I can stay for a longer time with a pupil who has got stuck (Teacher no. 39).

The computer functions so that everybody searches for her/his facts about that which we are working with. Everybody always finds something. My task is to make them proceed and sort facts (Teacher no. 17).

The other type of individualisation is often called negative or inductive. By this it is meant that the teaching patterns have gone from teacher-directed activities to the pupil taking greater responsibility for her/his own learning, which affects the quality of the learning in a negative way. The main criticism is aimed at the pupil getting too great responsibility for the choice of content and for the process itself of structuring her/his own learning.

Well, it's to be able to find any facts or to show the pupils anything (Teacher no. 21).

The result also shows that computer use is leading to a new trend in classroom work. The reason seems to be the mutual uncertainty of teachers and pupils about how free the working method in a One-to-One environment can be. The teachers now talk about learning together, a kind of explorative learning in which both parties cooperate.

… we can search together in a different way. That it is more, that we do it together rather than me thinking of it (Teacher no. 7).

Factual knowledge

The question of what facts are, where such knowledge exists, and to what degree it constitutes the very basis of the teachers’ professional identity is much discussed in an analogue context. In the curricula of Swedish schools, a distinction is made among four types of knowledge qualities the teacher must take into consideration in the teaching: proficiency, facts, understanding and familiarity knowledge. The differentiation of the knowledge concept dates back to Aristotle's (Citation2009) reasoning about the different qualities and applications of knowledge. In the present analysis, the focus is placed precisely on factual knowledge, which seems to be tantamount to certain and true knowledge (or conviction). Factual knowledge is also something that is fundamental for all other kinds of knowledge. That factual knowledge has to do with the subject teacher's identity is evident, but in One-to-One projects the result indicates that this dimension of the profession is changing.

It's probably to some extent that they have all the facts. They have got all the facts, so you don't have to communicate so many facts. But then you need certain things to be able to go further, so you have to take these in any case (Teacher no. 30).

The pupils already have all the facts, according to the above quote, as a consequence of which the communication pedagogy is considerably toned down. The computer is also seen as a complement to the paper book, where the computer is considerably more competent and is also seen as a prerequisite for high marks:

With the textbook you can take a pupil to a Pass or a Pass with Distinction. Achieving a Pass with Special Distinction requires a computer connected to the Net (Teacher no. 1)

, the widened text concept is easier to reach when they have got a computer. They also become much better at image analysis, I think (Teacher no. 9).

Presentations and syntheses

Presentations and syntheses are easier to make through searches on the Internet. The teachers describe in particular that complicated connections, knowledge at abstract levels, are easier to present and compile in a more easily accessible and informative way for the pupil.

I really praise YouTube to the skies […] it's terribly good to be able to be able to show, if a pupil asks me for example what does halal meat mean or something like that. So I tried to explain to them […] and it was a bit confusing. So I just looked it up on YouTube and there was a terribly good cut from a quite ordinary human being who had filmed it himself, about halal meat. Then I just pressed Play and after that they understood (Teacher no. 13)

Communication

The teachers state that work with computers makes the communication increase between pupils and teachers and between the school and the pupils, and that it facilitates the work. The pupils’ works are visible as they can see each other's works via the Net. The control on the part of the teachers also increases through openness and communication.

The communication is becoming much easier. Both to pupils and to parents (Interview 3, Lina).

Yes, an enormous advantage is of course that we can easily gain access to each other's works. Google apps for example are terrific. Also that we can place things in Schoolsoft, that we have been able to communicate in a simple way. That we can supervise them, I […] can send information and I can help them even if I'm not here physically, so that possibility has increased. They are not dependent, if they place everything on Schoolsoft, they never have to worry about not having handed in, and it's easy for me to check that they have handed in (Teacher no. 4).

Category 2

The computer in education makes no difference

This category is extremely rich and multifaceted. It concerns a highly essential part of the mission of education and teachers – the very issue of knowledge. The category consists of four subcategories: learning through teaching, the teacher as the foremost resource, the computer as a substitute for weak subject knowledge, and knowledge ambivalence in the subject teaching.

Learning through teaching

The common opinion in this category is that the computer in a One-to-One project does not make any difference at all from the previous situation as regards the learning itself. Learning is a consequence of the teacher's teaching and nothing else. The computer does not play any role when it comes to the pupil's possibilities to conquer new and necessary knowledge since the computer ‘does not know anything about the subject itself’. The computer is instead seen as a disturbing factor because it takes a lot of attention away from what is important in education.

[…] I have my knowledge of the subject and it works excellently, I think. A computer doesn't know what the goals are … it cannot itself say things like ‘check up on this, it's this you must learn – not that’. I think that … it's sometimes a problem (Teacher no. 7).

Computers are terribly expensive and I cannot see any difference from what it was like before. There's mostly a lot of larking about … a lack of concentration, if I don't go in and tell them to stop (Teacher no. 41).

The teacher as the foremost resource

This category contains the concept that nobody knows the subject content of education better than the teacher. Well-educated teachers in command of the depth and breadth of their subject(s) at every point superior to a computer by virtue of the teacher knowing how the subject is structured, what the most important and decisive knowledge of the subject is, how it is to be learned and evaluated in relation to objectives and national tests. The teacher also has an advantage as regards thinking in terms of partial knowledge goals and goals governed by curricula and syllabuses.

Of course we must have digital resources at school, but I'm still the best when it comes to teaching them (the pupils) what they must learn. I also know exactly what one must know to be able to go on to and understand the next step, so to speak. The computer cannot do that – not yet anyway (Teacher no. 38).

I'm glad that I'll retire soon. The computer is enormously overestimated and I have … well, become reduced to some kind of coach, or what is it called? I know what I can do. I know what the pupils should know. That is good enough (Teacher no. 2).

The computer as a substitute for weak subject knowledge

Subject theoretical knowledge carries great weight in parts of the data collected and analysed here. A general opinion is that subject competence constitutes the teacher's clearest competence basis. If one does not know one's subject, one cannot manage their professional mission in a correct and proper way. The statements also contain a criticism that is generation-related. In the group of younger teachers a criticism is noticeable of the older teachers for being weakly competent in how the computer can be used in teaching, at the same time as older teachers express the opinion that younger teachers have weak subject knowledge, which makes them hide behind the computer. The older teachers more often see that a lack of subject theoretical knowledge among newly educated teachers contributes to the professional identity itself being eroded in favour of trite, superficial and ignorant computerisation of the teaching. The consequence is that the pupils are learning less and less at school.

I've got so damned furious now that I think that things have gone too far. The new teachers do not know anything compared to us who are older. Only surface. No depth at all. Then it's easy to praise the computer to the skies … it's supposed to solve everything. It will go to the dogs. Believe me! (Teacher no. 8).

Some teachers, most often those who have worked for some time, they say many times that they don't understand how they should be able to use the computer in the teaching. I think that's right … (Teacher no. 22).

Knowledge ambivalence in the subject teaching

In recent years, the concept of knowledge has become increasingly complex. This opinion emerges in the data in combination with the paradoxical fact that pure subject knowledge in education has become increasingly clear and austere through management by objectives and the national and international tests having homogenised the knowledge concept. The teachers’ conception is that ‘everything is on the Net’ and that it is an important resource but also something that disturbs in the everyday work with the subject knowledge. The pupils want to search themselves and often find usable information and knowledge. Just as often they are swept along and away from the main line, which lies within the framework of what the teacher thinks is the central content and what is specified in the knowledge goals of the syllabuses. The ambivalence is tangible – the balance between free and controlled learning constitutes a problem.

Sometimes we must work freely, a eh searching, or … well, what is it called … they search for facts that are sometimes very good but just as often completely up in the clouds. Of course, they must search themselves, be creative and all that, but for me this means a lot of extra work … the uncertainty about whether it's really the right knowledge that they find (Teacher no. 27).

I mean, how can I evaluate every page they land on. In my subject, there are lots of crazy people who write all sorts of stupid things, but on the other hand they must learn to evaluate these things themselves. I'm worried about my own trustworthiness in the classroom (Teacher no. 3).

Category 3

The computer in education is changing the subject knowledge

Because of the possibilities the computer offers in education, especially the One-to-One projects where all pupils have their own laptop, the teachers’ traditional subject competence is regarded as insufficient. At the same time, this category shows that teachers can handle an ordinary teaching situation, where precisely digitalised information and knowledge are constantly present companions, where it is seen as a complement or even as a prerequisite for a new type of teaching and a different type of learning. Teachers whose opinions fall into this category have developed an alternative way of understanding knowledge, quite often in polemics with a more traditional concept of educational knowledge where management by objectives and national agreements on what important knowledge should be are prevalent.

The opinions in the category may be seen as progressive and elaborated, definitely as digitalised in the sense that the computer's potential and resources are seen as the conductor in conceptions of knowledge and in future learning in schools. The category contains innovative and entrepreneurial features characterised by seeing things beyond what is obvious.

Internet knowledge before subject knowledge

This category contains opinions where the teacher bases all their subject teaching on information and knowledge available on the Internet. The printed teaching materials have been replaced with digital knowledge artefacts, and teaching has been transformed into a creative workshop for learning, where every pupil is seen as a collective resource. Classroom work is compared to the working process in industry and trade, where the group's ability to solve problems and innovative power are superordinate to the individual. This category is sparsely represented in the data.

I don't look very much at the objectives and I know what I can do. In a knowledge society like this it is the creative force that is the most important thing, that they learn to cooperate and that they dare to rely on their own ability. The computer is … a, a fierce tool and I think that is has sort of come from God (Teacher no. 8).

You say subject knowledge. Okay. What you need to know … you find it now in a jiffy. Don't you! What you don't find and what you must learn at school is to combine what everybody knows into something new. […] The objectives of the curricula – have you read them? They are old-fashioned … the way of regarding knowledge as goals is old-fashioned, I think (Teacher no. 21).

The computer requires broader and deeper subject knowledge

In this category, the teachers’ opinion constitutes a relation between the information and knowledge that can be taken from the Internet and the subject knowledge the teachers have acquired and developed as a consequence of subject theoretical and disciplinary studies within the framework of their teacher education and in their own disciplinary competence development. It is evident that this category contains intra-disciplinary knowledge conceptions in the encounter with a mobile, stable, uncertain, rich, transitory, reliable, unreliable etc. Internet. The teachers’ opinion is that the Internet's great potential requires broader and deeper subject knowledge, which also includes clear scientific dimensions that over and above the actual factual knowledge also presuppose competence in critical examination, in how a dialogue is conducted with researchers and in how transformations can take place between traditional subject knowledge and the new achievements in the subject being made and presented on the Internet. This category also contains explicit needs for being able to follow scientific journals within one's own subject as well as didactic knowledge that can show what knowledge the pupil has, how the objectives are formulated and how these two manage in relation to scientific breakthroughs and changes within one's own subject.

It has become more difficult to be a subject teacher – earlier you had your education and the teaching materials authors’ prioritisations in the subject. If you were also one chapter ahead of the pupils … It's completely different now, the demands on me as a subject expert have been considerably raised … mostly for the better. It's kind of more interesting to be forced to surf along on this wave. But considerably more difficult to make things work (Teacher no. 40).

One-to-One has really forced me to sharpen my subject knowledge! (Teacher no. 11).

Discussion and conclusions

The results show that digital resources such as portable computers in One-to-One projects in schools are regarded by active subject teachers as something important and positive, even if there is also doubt about their own competence. The result supports Angeli and Valanides’ (2008) proposal that Shulman's PCK must be widened. Our conclusion is, however, that a D must be added to PCK so that the subject teacher competence is described as Digital Pedagogical Content Knowledge, namely DPCK.

An important finding is that the subject teacher competence's analogue constitution must be complemented with digital competence since the teachers state that it is precisely the possibilities afforded by the pupils having a computer each that raises new demands for deepened and broadened subject competence in combination with the computer being seen to a high degree as a prerequisite for the teacher's competent work. A comparison with previous research such as (Loughran, Berry and Mullhall Citation2012; Chai, Koh and Tsai Citation2013) shows that the teacher's content knowledge during the last few years has become increasingly more sophisticated and developed. This study shows that content knowledge and knowledge of how a computer can be used for effective learning in school are being integrated. Subject development must be accompanied by knowledge of the computer's communicative potential in its relation to how subject descriptions in terms of content are made on the Internet and how the computer is an integral part of the pupils’ everyday life. Precisely the relations among the teaching profession – everyday knowledge – educational knowledge – and the pupil's digital life-world are seen as fundamental when it comes to being correctly able to work and act as subject teachers in digital times.

A surprising part of the result is that the subject teachers entertain the opinion that it is impossible to achieve the most advanced level of the syllabuses’ goals together with the pupils without the aid of online computers. This might imply that the abstraction levels required in order for pupils to be able to get the highest marks are now so difficult to communicate in an analogue way that films from YouTube, demonstrations presented online by international research laboratories or similar things are required in order for schools to be able to show this type of knowledge. The consequence of such an opinion is that the gap among the different frontlines of the sciences has been stretched in recent years in relation to the knowledge and resources a local school has at its disposal. If this observation is correct, the computer in education will acquire an increasingly prominent place in teaching. This development is natural since the competition and knowledge society is making greater and clearer demands on every individual to acquire competencies that are attractive in both the education system and professional life and for personal and individual opportunities to follow an increasingly intense development.

The possibilities for individualisation are of critical importance in schools with One-to-One. The teachers here make a fruitful distinction between positive and negative individualisation. With the aid of the computer the subject teachers urge on positive individualisation through the pupils searching for information and knowledge that they are in a phase with. No one studies websites that are too simple and banal. Nor does anyone stick to sites that are difficult to understand or impossible to handle. The pupils go to information and knowledge that are on a level with their own development and that lie within what may be called the proximal zone. Vygotskij (Citation1978) defines this zone in terms of:

[…] the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance, or in collaboration with more capable peers (Vygotskij Citation1978, 86).

The computer is replacing the teacher (the adult) here and can in the interaction with the pupil offer the mentioned development potential.

Another aspect of the result is that the teachers experience that control over the pupil increases within the One-to-One framework. This observation is directly contrary to the notion that the computer gives the pupil complete freedom to travel in cyberspace. This is related to the fact that the pupils have all the material in one place – in the computer, that the teachers can see what an individual pupil has done and when this took place. Further, that all information that is sent to the pupil or her/his parents is acknowledged when the e-mail has been opened. The possibility to control pupils’ activities and performance in other subjects than one's own can also be checked. The total picture of a pupil has never been as good as in schools with One-to-One.

The question should be discussed of whether this is a development that is only positive. The control society is also sweeping across countries and nations that have traditionally been open and free. The individual's integrity is in this way being threatened in many societies and the information that a school or an individual teacher can collect about one single pupil is very extensive. This is probably one part of One-to-One that will have to be studied further – the part that may be called digital-in-the-world existence or, simply, DPCK.

The result indicates that the teachers experience that it has become more difficult to be teachers in One-to-One schools. The subject knowledge the subject teachers have from their university studies has for many of them provided a secure and stable foundation to stand on. By virtue of their superior subject knowledge subject teachers have had preferential right of interpretation in the classroom. The teacher has decided the pace and when new knowledge items should be added to the old ones. The teacher has held the responsibility for progression and for how the pupil's performance is controlled and judged. In One-to-One this tradition is being challenged. Through the Internet the knowledge concept has become postmodern in the sense that local ‘truths’ are placed alongside each other. The fragile relation of knowledge to what is generally experienced as correct is now a painful struggle in every classroom. This results in the teachers developing a pluralistic and locally composed relation to knowledge when working in One-to-One, at the same time as the constructors of curricula and syllabuses deal with a knowledge concept that is static and where every component in the learning is presupposed to be evaluable. The study has thereby been able to identify one of the most important problem areas arising as a consequence of One-to-One: The presence of the knowledge concept in a field of tension divided into four parts. The Internet provides a transitory, preliminary and local knowledge concept; curricula and syllabuses presuppose a static view of knowledge with clear objectives where these are possible to judge in terms of different degrees of attainment (marks), ordered in logical sequences and with the claim to be understood in dichotomies such as right-wrong, good-bad; the subject teacher who is as it were in the crossfire between certain and uncertain knowledge; the pupil, who is expected to understand several sides of this complex in order to be successful at school parallel to being individually successful in everyday life.

All in all, the study shows that subject teachers working in One-to-One have to develop their subject competence in order to be able to safely examine and evaluate information and knowledge, supervise and develop the pupil's knowledge with the aid of digital technology and conquer a pluralistic knowledge concept that can match the areas of tension between what is preliminary and what is changeable. Kroksmark (Citation2011) has called this a stretched digital-in-the-world existence.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tomas Kroksmark

Tomas Kroksmark is a Professor of Educational Work at Jönköping University, Sweden. His research is currently based in preschool, elementary school and high school, and also focusses on teachers.

References

- Al-Khatib H. How has pedagogy changed in a digital age? ICT supported learning: dialogic forums in project work. 2012. http://www.eurodl.org/?article=382 (Accessed 2015-02-19)..

- Angeli C., Valanides N. Epistemological and methodological issues for the conceptualization, development, and assessment of ICT-TPCK: advances in technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPCK). Computers & Education. 2009; 52: 154–168. [PubMedAbstract] [PubMedCentralFullText].

- Aristotle. 350 BCE/(2009). The Nicomachean ethics. Greensboro, NC: WLC Books.

- Barbosa da Silva A. Svensson P-G., Starrin B. Kvalitativa analysmetoder. Kvalitativa studier i teori och praktik. 1996); Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Becker H. J., Ravitz J. L. Computer use by teachers: are Cuban's predictions correct? Paper presented at the 2001 Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Seattle. 2001)

- Bengtsson J. Med livsvärlden som grund. 2000; Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Chai C-S., Koh J. H-L., Tsai C-C. A review of technological pedagogical content knowledge. Educational Technology & Society. 2013; 16(2): 31–51. [PubMedAbstract] [PubMedCentralFullText].

- Condie R., Munro B. The impact of ICT in schools – a landscape review. 2007). http://dera.ioe.ac.uk/1627/1/becta_2007_landscapeimpactreview_report.pdf (Accessed 2015-02-19)..

- Cuban L. So much high-tech money invested, so little use and change in practice: how come? Paper prepared for the Council of Chief State School Officers’ Annual Technology Leadership Conference. 2000); D.C: Washington.

- Cuban L. Oversold and underused: reforming schools through technology, 1980–2000. 2001; Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

- Davis B., Simmt E. Mathematics-for-teaching: an ongoing investigation of the mathematics that teachers (need to) know. Educational Studies in Mathematics. 2006; 61(3): 293–319.

- De Nobile J. Primary teacher knowledge of science concepts and professional development: implications for a case study. Teaching Science – the Journal of the Australian Science Teachers Association. 2007; 53(2): 20–23.

- Dunleavy M., Dexter S., Heinecke W. F. What added value does a 1:1 student to laptop ratio bring to technology-supported teaching and learning?. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning. 2007; 23: 440–452.

- Fuchs T., Woessmann L. Computers and student learning: bivariate and multivariate evidence on the availability and use of computers at home and at school. 2004. http://www.res.org.uk/econometrics/504.pdf (Accessed 2015-02-19)..

- Heidegger M. Sein und zeit. 1927; Tübingen: Max Neimeyer verlag.

- Heidegger M. The question concerning technology and other essays. 1977; New York: Harper Torchbooks.

- Hennesey S., Ruthven K., Brindely S. Teacher perspectives on integrating ICT into subject teaching: commitment, constraints, caution, and change. Journal of Curriculum Studies. 2005; 37(2): 155–192.

- Hirst P. What is teaching?. Journal of Curriculum Studies. 1971; 3(1): 5–18.

- Ihde D. Postphenomenology and technoscience. 2009; New York: Suny Press.

- Ihde D. Embodied technics. 2010; Atomic Press/VIP.

- Ihde D. Heidegger's technologies. Postphenomenological perspectives. 2010b; New York: Fordham University Press.

- Ilomäki L., Kantosalo A., Lakkala M. What is digital competence?. 2011. http://linked.eun.org/c/document_library/get_file?p_l_id=16319&folderId=22089&name=DLFE-711.pdf (Accessed 2015-02-19)..

- Klafki W. Klafki W. Zur Unterrichtsplannung im Sinne kritisch-konstructiver Didaktik. Neue Studien zur Bildungstheorie und Didaktik: Zeitgemäße Allgemeinbildung und kritisch-konstruktiver Didaktik. 1993; Weinheim: Beltz Verlag.

- Kleiger A., Ben-Hur Y., Bar-Yossef N. Integrating laptop computers into classroom: attitudes, needs, and professional development of science teachers – a case study. Journal of Science Education Technology. 2010; 19: 187–198.

- Kroksmark T. Fenomenografisk didaktik – en möjlighet. Didaktisk Tidskrift. 2007; 12(17): 2007.

- Kroksmark T. Fenomenografisk didaktik. ACTA Universitatis Gothoburgensis. Göteborgs Studies in Educational Research. 1987; 63

- Kroksmark T. The stretchiness of learning. Educational and Information Technologies. 2011. Article 9308. In Print.

- Kvale S. The qualitative research interview: a phenomenological and hermeneutical mode of understanding. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology. 1983; 14(2): 171–196.

- Kvale S. Ten standard objections to qualitative research interviews. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology. 1994; 25(2): 147–173.

- Lave J., Wenger E. Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. 1990; Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Loughran J., Berry A., Mullhall P. Understanding and developing science teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge. 2012; Rotterdam: Sense Publ. 2nd ed.

- Merleau-Ponty M. The phenomenology of perception. 1962; London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Murnane R. et al . Who will teach?. 1991; Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Papert S. Why school reform is impossible. The Journal of the Learning Sciences. 1997; 6(4): 417–427.

- Pečiuliauskiene P., Barkauskaite M. Would-be teachers’ competence in applying ICT: exposition and preconditions for development. Informatics in Education. 2007; 6(2): 397–410.

- Prop. 2009/10:89 Regeringens proposition (2009/10:89). Bäst i klassen – en ny lärarutbildning Stockholm: Regeringskansliet.

- Rogoff B., Lave J. Everyday cognition: its development in social context. 1984; Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press.

- Säljö R. Digital tools and challenges to institutional traditions of learning: technologies, social memory and the performative nature of learning. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning. Special Issue: ‘CAL’– Past, Present and Beyond. 2010; 26(1): 53–64.

- Shulman L. S. Those who understand: knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher. 1986; 15(2): 1–22.

- Spear-Swerling L., Brucker P. O., Alfano M. P. Teachers’ literacy-related knowledge and self-perceptions in relation to preparation and experience. Annals of Dyslexia. 2005; 55(2): 266–296. [PubMed Abstract].

- van Manen M. Researching lived experience. 1990; Toronto: The Althouse Press.

- van Manen M. The tact of teaching. 1991; New York: State University Press.

- Vygotsky L. S. Mind in society: the development of higher psychological processes. 1978; Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wertsch J. V. Mind as action. 1998; Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wong E. M. I., Sandy C. L. I. Is ICT a lever for educational change? A study of the impact of ICT implementation on teaching and learning in Hong Kong. Informatics in Education. 2006; 5(2): 317–336.