Abstract

In educational contexts there are few topics that receive as much attention from adults as children's behaviour that is seen as challenging. Challenging behaviour has been a topic in many disciplines, such as education, child psychiatry, psychology and special education. Along with the definition of challenging behaviour, we can read about social and emotional difficulties or disruptive behaviour. In this article we examine the definitions of challenging behaviour in Finnish day care. Altogether 291 professionals answered an open-ended question. The results show a wide range of individually defined meanings where the focus is mostly on children in a problem-oriented way.

Introduction

In this study, we are interested in how early childhood education teachers and practical nurses describe challenging behaviour in day care. Lyons and O'Connor (Citation2006) argue that there are few topics within education that receive as much attention or cause as much concern for adults as children's behaviour that is seen as problematic. Children with challenging behaviour challenge teachers every day in many educational contexts (Lyons and O'Connor Citation2006). In the international literature and in education, according to Thomas (Citation2005), the term EBD (emotional and behavioural difficulties) is quite a widespread and often used term. Along with EBD, the term challenging behaviour is used. Identifying and describing challenging behaviour as it seen in early childhood education is important since we do not know enough about what the challenges or difficulties are in fact in the minds of day-care professionals today. It has been found that teachers feel that they do not have sufficient skills or tools to address behavioural problems and they feel worried knowing that such problems have significant negative outcomes (Fox and Smith 2007; Hammarberg Citation2003). In order to give support and plan effective interventions for day-care personnel and other caregivers we need to know more about this phenomenon from the actors themselves.

The context of the study is Finnish day care. In Finland, public day care is the mainstream service as 92% of all children in day care are in the public sector. An estimated 63% of 1- to 6-year-old children take part in day care. Further, 74% of all 3- to 5-year-old children and 41% of all 1- to 2-year-old children are in day care. About 80% of all the children had an all-day-care service, and spent about 8 hours a day in day care (see THL Citation2011, Citation2014). Thus, the majority of children aged 3–6 spend most of their waking hours in child groups in day-care centres. In Finland, the personnel in day care have either kindergarten-teacher-level education (about 33% with a Bachelor degree) or practical-nurse-level education (vocational education, secondary level). The adult-child ratio by law in whole-day care is 1:4 children under 3 years of age, and 1:7 when children are between 3 and 6 years of age. By adult, we mean either kindergarten teachers or practical nurses.

In this study, we analyse the written descriptions made by day-care personnel. In these written descriptions the language, the words, that are in use are seen as meaningful. Language is essential in many ways. Language shapes meanings, fosters the forming of different types of meanings, and clarifies or conceals connections between meanings and actions (Charmaz Citation2014). Language is an inseparable part of being human and is strongly involved in the developmental processes of the individual child (Jokinen, Juhila and Suoninen Citation1993; Lehtonen 2000).

Conflicting approaches to challenging behaviour

Lyon and O'Connor (Citation2006) note that, despite the fact that challenging behaviour attracts a lot of attention, its precise nature is open to discussion and debate. We can also talk about problem behaviour referring to behaviour that is challenging (Fox, Dunlap and Cushing Citation2002). In the literature, depending on the discipline or the setting, a variety of terms is used to describe challenging behaviour, social and/or emotional difficulties and disorders. Every branch of science or every branch of service has its own way to see, describe and define these problems.

According to Papatheodorou (Citation2005), challenging behaviour can be defined as a continuum of a repeated pattern of behaviour that interferes with learning or engagement in social interactions. Again, this is not always placed within one or another dimension such as aggressive behaviour or withdrawn behaviour, but is seen as a mixture of behaviours identified in a negative way. It is often considered that children are the problem in educational contexts (Thomas and Loxley Citation2002) which is the traditional way to look at this issue. According to this orientation, when children are seen as a problem, there is a need to plan the child's education individually. In these educational plans, teachers can specify the aims and the methods that could be used to make the identified children as ‘normal’ as possible. The goals are set for the individual child, while the pedagogical context has been very often ignored or forgotten (Pihlaja Citation2003).

Disruptive behaviour and oppositional defiant disorder, or wider descriptions such as externalising or internalising behaviour problems, refer to challenging behaviour. Externalising behaviour problems are characterised by aggressive, noncompliant and oppositional acts. Internalising problems refer to a lack of social skills manifesting as states such as withdrawal, anxiety etc. Descriptions in the literature of challenging behaviour more often mean externalised than internalised problems (Hammarberg Citation2003, 13; Powell et al. Citation2007, 81; Snell et al. Citation2012, 98). Further, according to Hammarberg (Citation2003, 41), when studying teachers’ low perceived control to manage challenging behaviour, it was most strongly related to externalising behaviour.

Identifying and describing challenging behaviour is important when considering the idea that the term challenging behaviour is to some extent socially constructed and varies across the settings in which the children are (Oliver et al. Citation2003). These kinds of labels or definitions of children are not transient, even the definitions of these problems seem to lie in a grey area. Further, the permanence of these kinds of problems is solid, the occurrence or prevalence is substantial, and these difficulties, problems or disorders concern many children, their parents and day-care personnel. Moreover, the growing acknowledgement that early signs of challenging behaviours can have severe long-term consequences has led to more concrete efforts to describe such behaviours across professionals, disciplines and service systems (Wright Citation2009).

The permanence and prevalence of problems assigned to social, emotional or behavioural difficulties have for a long time been one argument that makes this theme socially important. Many studies have stated that the prevalence or occurrence have for years been between 10% and 20% (Brauner and Stephens Citation2006; Campbell Citation1995; Pihlaja Citation2003, Citation2009; Pihlaja et al. Citation2010; Powell et al. Citation2007), and many studies have affirmed that there is strong evidence of the permanence of socio-emotional difficulties (Bayer, Sanson and Hepmhill Citation2006; Briggs-Gowan et al. Citation2006; Goodman and Goodman Citation2009; Mesman and Koot Citation2001; Morgan, Fargas and Qiong Citation2009). Brauner and Stephens (Citation2006) say that behavioural problems should be seen or identified early and allow children to be treated before they are ‘labelled’ as emotionally disturbed.

Many population-based birth cohort studies have shown that childhood psychiatric problems are developmental precursors for a wide range of negative outcomes (Achenbach et al. Citation1995; Goodman and Goodman Citation2009; Kim-Cohen et al. Citation2003; Sourander et al. Citation2005; Sourander et al. Citation2009). Powell et al. (Citation2007) talk about “unchecking this problem”. By this, they mean that even though these problems are noticeable we do not react to them early enough (Powell et al. Citation2007). To examine this ‘problem’, we need research focusing on children's authentic environments and also on the people who are responsible for the children and raise them. There are strong grounds for studying these problems and especially how professionals see them. Various studies and reports show that these problems entail huge costs for society, for the young and for all those with whom the child interacts (e.g., family, peers, educators). The costs that are associated with education include early and persistent peer rejection (Coie and Dodge Citation1998), mostly punitive contacts with teachers (Hammarberg Citation2003; Pihlaja Citation2003; Strain et al. Citation1983) and school failure (Tremblay Citation2000). It seems that this negative trajectory described in the literature and in many studies is the child's fate. The view taken towards these problems is extremely problem-oriented and dark. The reason we study day care is because the early years are arguably the most significant period of children's education, and their first encounters with the education system are therefore of fundamental importance (Blenkin, Rose and Yue Citation1996).

Defining and focusing the problems into a child is linked to the individual model of disability that has its roots in medicalisation. The individual model of disability has seen the problem, deficits or disorders placed in an individual. This tends to be a mainstream way to see children with disabilities or special needs not only in psychology and child psychiatry but also in education (Pihlaja Citation2003; Vehkakoski Citation2006; Vehmas Citation2005). In education, the traditional way to solve this ‘problem’ has been to segregate, to treat and teach these pupils in special classes, in special schools with special teachers (see Jahnukainen Citation2003; Kivirauma, Klemelä and Rinne Citation2006; SVT Citation2012). There has been growing criticism of both special education practices and research. According to Mallory and New (Citation1994), there is a gap between theoretical bases and practices in education because the theoretical bases of research are often neglected in practice.

In addition to the individual model, there is growing emphasis on the social model that shifts our view to the process during which we socially construct disability (Oliver Citation1996; Reindal Citation1995). According to this model, different communities and settings socially construct what is regarded as disability or as special. The social constructionist view of challenging behaviour, which is close to the social model, suggests that the identification of challenging behaviour varies across settings. For example, considering the day-care setting, the perception and descriptions about challenging behaviour can vary a lot among employees with different backgrounds. Consequently, challenging behaviour can be considered an undesirable activation or trait, related not only to personal character but also to context (Lyons and O'Connor Citation2006). For example, according to a Finnish study by Pihlaja (Citation2003) also internalised problems are considered challenging by early educators in the day-care context, which is not necessarily the case in basic education (see Kuula Citation2000). Finnish kindergarten teachers’ descriptions of social emotional problems can be divided into three different types also depending on the setting. These areas in typical day-care child groups and also in special day-care child groups are anxiety problems and peer relationship problems with disruptive or aggressive behaviour. In special groups disruptive or aggressive behaviour combined with specific learning difficulties was also identified (Pihlaja Citation2003). Similar types of these three areas were found in a survey conducted by Snell et al. Citation2012.

Wright (Citation2009) talks about three meta-discourses which classify children as ‘bad’, ‘mad’ or ‘sad’ referring to the challenging behaviour. Pupils with emotional and behavioural difficulties and challenging behaviour are often considered the most challenging group to manage within mainstream education (Scanlon and Barnes-Holmes Citation2013), also even in special education (Kuula Citation2000; Seppovaara Citation1998). The challenges perceived by teachers may be due partly to negative attitudes to these children (Pihlaja Citation2009, Citation2012; Scanlon and Barnes-Holmes Citation2013; Thomas Citation2005; Viitala Citation2000).

In the many different studies mentioned above we can find conflicting forces. By this we mean that even the definition seems to be in a grey area, there are still ‘facts’ about the prevalence, the permanence or the consequences. This makes the examination of what is seen as challenging behaviour in day care at least interesting. Our aim is to examine how employees in day-care describe children with challenging behaviour and what kind of meaning structure can be drawn. Can we draw one all-inclusive picture of it, or is it fragmented?

We start by describing the aims of the study and then go on to the methodology and results.

Research frame

Aims

The purpose of this study is to increase our knowledge and understanding about the day-care staff descriptions of challenging behaviour assigned to children. What are seen as challenges in a day-care context? The aim is to form a meaning structure of the challenges according to day-care personnel answers. Respondents wrote a description in response to an open-ended question: “Describe briefly what in your opinion is a child who has behavioural challenges or difficulties in day care”. This article forms part of a larger study about challenging behaviour in day carried out together with the Department of Education and the Research Centre for Child Psychiatry at the University of Turku. In the survey of this larger study we have also contributed other themes concerning this topic, mostly quantitative data that are not part of this article.

Participants

To obtain answers from right across Finland we selected participating municipalities by convenience sampling from the north, east and south of the country. In Finland, there are 320 municipalities and we chose 18 of them. The data were gathered via the Internet by the Webropol survey software. In Finland there are Internet connections in every kindergarten and especially principals have to use the Internet and IT in their daily work.

We sent the survey via the Internet to the heads of the early childhood education service at the municipal level and asked permission to do this research in the municipality. We obtained permission from all 18 municipalities to do the study. Data were collected from day-care staff in Turku, Oulu and Kuopio and smaller municipalities around these cities. Thus, 18 municipalities took part in this study (11 towns and 7 other municipalities), with 279 child groups and altogether 291 respondents by the deadline of our survey. In Finland, 78% of all inhabitants live in towns and 22% in other municipalities (Kuntaliitto Citation2014) so the ratio between towns and other municipalities in our study is analogous to the ratio in Finland. After receiving permission to do this study, we sent the survey to the managers of day-care centres who forwarded the questionnaire to the child group staff. We received answers from all 18 municipalities.

In the survey we gathered background information from the respondents (gender, education, working years, age), about the child group (number of children, form of the day care etc.), and the municipality (size, its location). The mean of the respondents’ age was 43.7 years and most respondents were females (98%), which is the case in Finnish day care. Their job titles were kindergarten teacher (56%), practical nurse (35%), special kindergarten teacher (3%), principal (3%), or some other (3%). The educational background varied: 37% had a kindergarten teacher degree, 22% a social pedagogue background, 3% a special kindergarten teacher degree, 30% a practical nurse's diploma, and 8% some other kind of secondary educational background. The respondents had a lot of working experience; 51% had worked in day care for over 15 years, 33% had 5–15 years’ experience, while 16 percent of the respondents had less than 5 years’ working experience. The share of kindergarten teachers in Finland is about 33% of the pedagogical-responsible employees, and the nurses’ share is about 66% (Pihlaja, Rantanen and Sonne Citation2010; THL Citation2011). In early childhood education, kindergarten teachers have greater responsibility than nurses and have a leading role in the work team so, from this point of view, these answers describe the ideology of the group well.

The survey was sent to child groups in which the children were 3–6 years old, and the mean age was 4.8 years. Most children were in ordinary child groups (80%). Some (15%) were in so-called special groups (5% missing information).Footnote1 In special groups where there is usually a special teacher the number of children is fewer than in ordinary groups. Special groups are, in Finland, mainly integrated groups, where most children are typically developed and only some have special educational needs (Pihlaja Citation1998; Citation2003; 2010).

Description of the methodology and analysis

The main idea of this study was to construct a meaning structure of the descriptions expressed by day-care personnel related to challenging behaviour of children in day care. Open-ended answers formed qualitative material for the qualitative analysis process in which we used the ideas of Grounded Theory (GT); it especially provides “tools for analysing processes” (see Charmaz Citation2008, 202). When examining words or language the information the respondents gives us is something about the individual body of knowledge based on action, context and culture where is it used (Berger and Luckman Citation1994; Burr Citation1995). According to this social constructivist view, every individual expresses something that is created socially in the day-care context and in day-care culture. The original Grounded Theory has been developed further and Charmaz (Citation2000; Citation2008) writes about a constructive way to use GT. This means that researchers take a reflexive stand on modes of knowing and representing life that have been studied. CitationThornberg (2012) criticises rigid inductive inquiry with delaying literature review. We share this constructive view. No researcher carries out his or her inquiry in a social vacuum. As Charmaz (Citation2008, 207) states, “the entire research process is interactive, we bring past interactions and current interests into our research and we interact with our empirical materials and emerging ideas as well”. We gathered the material and analysed it by our lenses in the light of earlier theoretical and practical knowledge. The ideas we use here are connected with the analysing process by emphasising the original data. We did not make any categories or classes from any earlier used theory, but still the coding system leans on our earlier knowledge. The coding system we have here is used widely in GT. This system is: initial and focused coding, axial coding and theoretical summary of the results (see Charmaz Citation2008; Hildenbrand Citation2004; Ryan Citation2014; Strauss and Corbin Citation1996).

First, we formed one document from all these open-ended answers and loaded it into N*Vivo for Windows (see CitationQSR International), which is a software for qualitative research. N*Vivo helped us to organise the material and made it easier to analyse it. After reading the material, we coded (=initial coding) keywords with meaningful context. “A challenging child is in my opinion aggressive” or “the challenges can be seen daily as restlessness”. We coded keywords with meaningful context, and the coverage of references was in the whole data 85%. In the first step, the material was analysed in a research team. In this first process (=initial and focused coding), two writers of this article and four special education master degree students took part. During this process, as a team, we developed the subclasses (N=28) for this material (see Hildenbrand Citation2004, 20–21), and the peer reliability was good, over 90%. After this phase, the writers are responsible for the rest of the analysis process. By examining the material, we were seeking similarities and differences that could lead to a reduction in the number of classes (see Appendix 1).

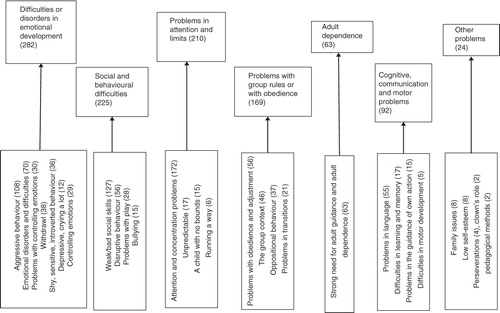

After focused coding with altogether 28 subclasses, we read the material critically and compared the subclasses. This axial coding process helped us to form seven (7) major classes from these 28 subclasses. In this phase, we integrated classes that had similarities either theoretically or in functionally meaningful activities in day care. Theoretically words or sentences that belong together, e.g. to emotional development and its problems formed one major class. In the process of this axial coding, we actually formed umbrella terms or major classes (see ).

Results

The most frequently mentioned of all the subclasses addressed attention problems (172), weak or bad social skills (127), aggressive behaviour (108), emotional disorders or difficulties (70), and problems with obedience and adjustment to the group (65) (see Appendix 1). Picture 1 shows the result of analysing these 28 subclasses and the reduction to seven (7) major classes.

Emotional problems formed the largest major class in this study. The development is seen as a source of challenging behaviour when the child is aggressive or violent, has emotional disorders or difficulties, is shy, depressive, sensitive, or introverted, or has problems with controlling his/her own emotions. These examples are close to the traditional classification of emotional disorders: externalised and internalised emotional difficulties. Altogether, the aggressive behaviour was the largest problem group, while depressive or introverted problems were less often cited compared to aggressiveness in our study. The line between typical and atypical development is sometimes hard to draw in early childhood, and this is also seen in our material. According to Margaret Briggs-Gowan and Alice Carter (Citation2006), social-emotional difficulties and problems belong to typical development, but they become problematic when they are particularly strong or weak, or repeated particularly often.

Social and behavioural difficulties included weak or bad social skills, disruptive behaviour, problems with play or bullying. In this class, the relationship with other people, especially with other children, is described as problematic. This gives a picture of a child who is having social problems with peers, and needs support and help in this area. In this we can actually interpret and see another child or adult as being problematic to a child who is seen as challenging. Even the challenges are mentioned as disruptive in this class, there are no references to violent actions.

Problems in attention and concentration were often mentioned and the descriptions were e.g. a child cannot sit still or is restless. In this class we also included boundless children, and children who ran away or were unpredictable. What the respondents meant by unpredictable we do not know, for they just wrote one word, unpredictable. According to these descriptions we can easily see children moving and buzzing around without focus or limits like ‘bees’.

The group context was clearly seen as problematic for some children. Too many children in a group or joining the group were seen as a challenge. Transitions during the day are normal and repeated actions in day care were also interpreted as being challenging. In child groups, some routines and rules must be adjusted to or obeyed, which is not easy for some of the children according to respondents. Elements belonging to group life are, for example, order, climate and authority of the group. Are these children lost in a group? Is it hard to follow group rules and adults’ instructions in a context like this? Do these children have the same kinds of problems at home? Or do the personnel expect too mature behaviour from the children?

The strong need for adult supervision and guidance was also mentioned as challenging by respondents. Children missing their mothers or hanging on the teacher's sleeves were challenges to early childhood education professionals. Did these children feel insecure in day care, or did some of the respondents expect children (again) to be more independent and mature than they actually were? The independence and to manage by one's own are highly valued in Finnish day care both by parents and by personnel (Ojala Citation1997).

Difficulties that are linked to other developmental areas were also mentioned as challenging. According to respondents, challenging behaviour was also mentioned if the child had problems in language, speech or the use of the voice, or in learning and memory, which are all part of the cognitive development. Difficulties in problem solving or in understanding or with sensor regulation were mentioned. The guidance and control over the child's own activities and also difficulties in motor development, like clumsiness, were also expressed. In the studies dealing with social and behavioural difficulties or emotional, behavioural and social difficulties (EBD) in day care, we could not find this kind of class from the answers (Pihlaja Citation2003, 2010; Viitala Citation2014).

The “other problem class” was formed by answers like self-image, self-esteem or family issues. Some respondents mentioned perseverations or child's need for “different pedagogical methods” as a source of challenging behaviour.

In determining the meaning structure of challenging behaviour according to descriptions by professionals in a day-care setting, we found that the descriptions varied a lot. All professionals have their own words for telling this. These individually made descriptions are focused on the child, on the context or on the adult-child relationship. Descriptions had something in common, by this we mean that the children were seen as the origin of the challenges, they had difficulties, disorders, delays, or a lack of something. This interpretation has similarities with the individualistic interpretation repertoire of disability or special needs. Besides this, there are also elements concerning the context (child group) or adult-child relationship which come close to the social model. Problems with group context include the large child group, the transition practices and the group rules that are hard to follow. In educational settings, the routines and the curriculum are partly hidden and partly shared and known (see Broady Citation1986; Karjalainen and Siljander Citation1993), which makes it difficult for workers to reflect on their own part in the routines or the implementation of the curriculum.

In the challenging adult-child relationship, the roles of the adult and the child are meaningful. In the class “Need for adult guidance” a child is seen as demanding something from an adult, who defines this demand as challenging. Do the adults expect too much from the child, should the child be an independent person?

When analysing the answers that deal with “Difficulties in attention and limits” our interpretation can be that this category is dealing partly with the child, partly with the adult, and partly with the day-care context. There might be some discrepancy between the adult expectations toward children's behaviour and the competence of the children, or the day-care context is really too challenging for children to handle. One can also wonder whether children might have difficulties orienting themselves in space and time. In these, both social and contextual elements are included. The “Other problems” category is really on the border of this entity: still we can find the focus on the child, or the context, or the adult-child relationship.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to increase our knowledge and understanding about how the day-care personnel describe challenging behaviour. In this study, we used a questionnaire and respondents wrote their answers, and of by using an interview we might have a deeper understanding. However, in this study we could construct a wide picture of challenging behaviour from the material. To assess the truthfulness or credibility of this study the reader can take part and for this we have described the material rather broadly. The openness in qualitative inquiry is important and one reason for this is that “the social conditions in a society can form a silent frame on inquiry within it” (Charmaz Citation2014, 1076). Researchers are always part of this silent frame. Still some reflections can, and should, be made by researchers. In our study, the classes cover a wide range of empirical material, and we have made systematic comparisons between the categories, which refer also to credibility (see Charmaz Citation2008). Inter-subjective transparency of qualitative research is an essential criterion of the quality of qualitative research that we brought about by describing the original material, and also by presenting the analysing process (Knoblauch Citation2004, 356–357). Transferability can also be seen as one criterion of qualitative inquiry (e.g. Denzin and Lincoln Citation2008), which was strengthened in our study by the samples we got from different day-care units and from different parts of Finland.

Even if the question we asked respondents emphasised the child and problems, the answers were not only focused on the problematic individual. To this question we obtained a really wide range of answers that made our picture at least wider if we compare it to earlier research in day care about social and emotional difficulties (see Pihlaja Citation2003, Citation2009; Viitala Citation2014). We found answers from different areas and from different levels. The definition has a wide range of subjective meanings. In the results we can find interpretations that emphasise individual and social models of disability. The individual model of disability emphasises disorders, deficiencies, deviations, lack of something, or limitations that are individual characteristics (see Oliver Citation1996; Reindal Citation1995; Vehmas Citation2005; Vehkakoski Citation2006). This individual model is still the mainstream interpretation of disabilities or special needs also with children who are assessed as having social and/or emotional difficulties (Pihlaja Citation2008; Pihlaja Citation2012; Vehkakoski Citation2006; Vehmas Citation2005). According to this interpretation, it seems that challenging behaviour is seen as something which is within the child and therefore beyond, e.g. teachers’ or nurses’ influence, which is not the case in the social interpretation. If the pedagogy is not working, the fault is seen within the child or in the home, not in the methods or institutional activities or structures in education (Mietola and Lappalainen Citation2005; Pihlaja Citation2003, Citation2008).

According to this study, the context of day care was seen also to some extent as challenging, despite our study question to respondents. This led us to understand that there are also some elements connected with the social model of disability where the origin of the problems or disability is in organizational practices or in structures (see Oliver Citation1996; Reindal Citation1995; Vehkakoski Citation2006; Vehmas Citation2005). These obstacles in our study can be connected to physical and structural elements of day care in particular, as Hirst and Cooper (Citation2008) say, to the choreography of the classroom. Practices relating to the physical design of the environment including schedules, routines, and transitions are also one factor according to Corso (Citation2007) when reducing challenging behaviour in class rooms. Even in the case of the routines and transitions in day care that are planned and carried out by personnel, the respondents did not write about their own part in these. Respondents did not say anything about their role in these, which could also be associated with the social model of disability. Does the absence of the personnel's own role in this involve the reflectivity of the teachers and practical nurses (see Marcos, Miguel and Tillema Citation2009; Pihlaja and Holst Citation2013)?

The challenges linked to children's development in this study are connected to different levels and to different areas of development (e.g. learning, behaviour). The levels shift from typical to atypical behaviour, and the line between them is hard to draw. The extent of the descriptions was wide, moving from shyness to aggression, or from learning disorders to family issues. In spite of this, we found that a lot of context-bound similarities, for example, aggressiveness, difficulties with other children, and concentration problems are easily noted in day care. In this study, it is obvious that the descriptions of challenging behaviour are also bound to the person defining it. It is a risk when in education these kinds of definitions or labels of children are based on personal opinions or views: these labels might follow the child from a child group to another, for there is strong evidence of the permanence of these kinds of problems. The child can also internalise the negative expectations and attitudes that the persons around him/her express. Can we see in our results “half-understood ideas about disturbance” (see Thomas Citation2005, 68) disturbances that are in a grey area.

The results of this study also make one wonder whether the expectations concerning the social emotional competence and also the learning of the children in day care are too high. How competent and mature should a 4-year-old girl or boy be? Do day-care personnel have a picture of an ideal child in their minds, a picture of a competent child? The ideal child who has good social skills, obeys and respects adults, does not demand too much from an adult, is empathic and has a good readiness for learning and guiding his or her own activities. According to CitationSjöberg (2014), a large group of students in teacher education states that every child is, or should be, competent, also in preschool. She noted that a competent child activates self-motivated, independently and responsibly in their learning (Sjöberg Citation2014). Societies today value efficiency, excellence and competence. Have these expectations and values reached early childhood and early childhood education without reflections on the nature of childhood and what is good education in childhood? We can also ask whether the child groups per se are currently too challenging; many employees having a lower level of education and too many qualifications, with a continuously changing group structure, and with too many children in a group (Pihlaja, Rantanen and Sonne Citation2010). We think that personal views of challenging behaviour linked to too high expectations forms an uncertain basis for education.

The results of this study raise new questions and themes to be examined and developed in day care. How can the personnel be helped with the challenges they experience in early childhood education? How does their educational background affect the ways personnel see and interpret these difficulties? In our interpretation, the challenges for the most part dealt with the individual child and this interpretation needs a wider meaning structure that helps to turn the gaze toward the pedagogical setting and the processes in it as a whole. In this process, the social model of disability may turn teachers’ and nurses’ attention toward analysing the setting, attitudes, instructions and routines that form the psychological, social and physical context in which children develop and learn. The educational context that supports and gives positive guidance to social behaviour can work with all the children in the child group according to CitationOliver, Wehby and Reschly (2011) and in this way the grey area might become smaller.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Child Psychiatric Research Unit and The Strongest Family research group with Professor Andre Sourander for co-operation.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Päivi Pihlaja

Adjunct professor Päivi Pihlaja is working as a university lecturer in special education. She completed her PhD in 2004 and her dissertation dealt with early childhood special education in day care. Her research interests are in special education and early childhood education focused on social and emotional difficulties.

Tanja Sarlin

Master of Science Tanja Sarlin has over 12 years’ experience in the field of early education. She has worked as both a kindergarten teacher and a kindergarten manager. She worked 5 years at the University of Turku as a research coordinator in the Research Centre for Child Psychiatry in the Faculty of Medicine. Currently she is working as a development manager in Sateenkaari Koto which is an organization providing early education and family services in Turku region. She is working on her PhD studies in Department of Education, University of Turku.

Terja Ristkari

RN, MNSc Terja Ristkari has been working in the psychiatric field since the early 1980s. She has rich experience in psychiatric nursing and psychotherapy. In research work she has been working for over 15 years and is currently working at the University of Turku Research Centre for Child Psychiatry as a project manager.

Notes

1 The number of children in child groups varies. In Finland, the number of children depends on the number of teachers/nurses. In one child group (3–6 years old), when children need all-day education and care, the ratio is 7 children to 1 adult e.g. one kindergarten teacher (or 2) and 2 nurses (or 1). In part-day care there are 25 children, and 2 adults, or 14 children and one kindergarten teacher. In this study, the most typical group size was 22 (Mo), the mean was 19 and the median 20. In child groups there were 20–24 children (38%), 15–19 children (28%), 10–14 (17%), 24–36 (11%) or under 10 (6%) children.

References

- Achenbach T. M., Howel C. T., McGonayhy S. H., Stanger C. Six years predictors of problems in a national sample: III Transitions to young adult syndromes. Journal of American Academic Child Adolescence Psychology. 1995; 34(5): 336–347.

- Bayer J. K., Sanson A. V., Hemphill S. A. Parent influences on early childhood internalising difficulties. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2006; 27(2): 542–559.

- Berger P., Luckman T. Todellisuuden sosiaalinen rakentuminen: tiedonsosiologinen tutkielma [The Social Construction of Reality. 1994; Helsinki: Gaudeamus. first printed 1966. In Finnish Vesa Raiskila].

- Blenkin G., Rose J., Yue N. Government policies and early education. European Early Childhood Research Journal. 1996; 4(2): 5–17.

- Brauner C. B., Stephens C. B. Estimating the prevalence of early childhood serious emotional/behavioral disorders: challenges and recommendations. Public Health Rep. 2006; 121(3): 303–310.

- Briggs-Gowan M., Carter A. BITSEA. Brief infant–toddler social and emotional assessment. 2006; San Antonio: PsychCorp.

- Briggs-Gowan M. J., Carter A. S., Bosson-Heenan J., Guyer A. E., Horwitz S. M. Are infant-toddler social-emotional and behavioural problems transient?. Journal of American Academic Child Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006; 45(7): 849–858.

- Broady D. Piilo-opetussuunnitelma [The hidden curriculum] . 1986; Tampere: Vastapaino. (Translated from Swedish Den dolda läröplanen, in Finnish by Kämäräinen, P., Neste, M. and Rostila, I).

- Burr V. An introduction to social constructionism. 1995; London: Routledge.

- Campbell S. B. Behaviour problems in preschool children: A review of recent research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1995; 36: 113–149.

- Charmaz K. Denzin N. K., Lincoln Y. S. Grounded theory. Objectivist and constructivist methods. Handbook of Qualitative Research. 2000; Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. 509–535.

- Charmaz K. Denzin N. K., Lincoln Y. S. Grounded theory in the 21st century: Applications for advancing social justice studies. Strategies of Qualitative Inquiry. 2008; Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. 203–242.

- Charmaz K. Grounded theory in global perspective: reviews by international researchers. Qualitative Inquiry. 2014; 20(9): 1074–1084. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1077800414545235.

- Coie J. D., Dodge K. A. Aggression and antisocial behaviour. Handbook of Child Psychology. 1998; 5th ed, New York: Wiley & Sons. Social, emotional, and personality development. W. Damon (editor in chief) and N. Eisenberg (vol. ed.).

- Corso R. M. Practices for enhancing children's social-emotional development and preventing challenging behavior. Gifted Child Today. 2007; 30(3): 50–56.

- Denzin N. K., Lincoln Y. S. Denzin N. K., Lincoln Y. S. Introduction: the discipline and practice of qualitative research. Strategies of Qualitative Inquiry. 2008; Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. 1–44.

- Fox L., Smith B. J. Issue Brief: Promoting Social, Emotional and Behavioural Outcomes of Young Children Served Under IDEA. 2007. Center on the Social and Emotional Foundations of Early Learning and Center for Evidence-based Practice: Young Children with challenging behaviour. http://challengingbehavior.fmhi.usf.edu/do/resources/documents/brief_promoting.pdf (Accessed 2013-12-12).

- Fox L., Dunlap G., Cushing L. Early intervention, positive behaviour, support and transition to school. Journal of Emotional and Behavioural Disorders. 2002; 10(3): 149–157.

- Goodman A., Goodman R. Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire as a dimensional measure of child mental health. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009; 48: 400–403.

- Hammarberg A. Pre-school teachers’ perceived control and behaviour problems in children. 2003; Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala dissertations from the Faculty of Social Sciences 123.

- Hildenbrand B. Flick U., von Kardorff E., Steinke I. Anselm Strauss. A. Companion to Qualitative Research. 2004; London: Sage Publications. 17–23.

- Hirst E., Cooper M. Keeping them in line: choreographic classroom spaces. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice. 2008; 14(5–6): 431–445.

- Jahnukainen M. Laman lapset? Peruskoulussa erityisopetusta saaneiden oppilaiden osuuksien tarkastelua vuodesta 1987 vuoteen 2001 [Children of economic depression]. Yhteiskuntapolitiikka. 2003; 68(5): 501–507.

- Jokinen A., Juhila K., Suoninen E. Diskurssianalyysin aakkoset. 1993; Vastapaino, Tampere.

- Karjalainen A., Siljander P. Miten tulkita sosiaalista interaktiota? [How to interpret social interaction]. Kasvatus. 1993; 24(4): 234–246.

- Kim-Cohen J., Caspi A., Moffitt T. E., Harrington H., Milne B. J., Poulton R. Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: developmental follow-back of a prospective-longitudinal cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003; 60(7): 709–17.

- Kivirauma J., Klemelä K., Rinne R. Segregation, integration, inclusion – the ideology and reality in Finland. European Journal of Special Needs Education. 2006; 21(2): 117–133.

- Knoblauch H. Flick U., von Kardorff E., Steinke I. The future prospects of qualitative research. A Companion to Qualitative Research. 2004; London: Sage Publications. 354–358.

- Kuntaliitto. Tilastot [Statistics]. 2014. http://www.kunnat.net/fi/tietopankit/tilastot/vaestotietoja/Sivut/default.aspx.

- Kuula R. Syrjäytymisvaarassa oleva nuori koulun paineessa: Koulu ja nuorten syrjäytyminen [Risk of social exclusion of the young in the pressure of the school] . 2000; Joensuu: Joensuun yliopisto.

- Lehtonen M. Merkitysten maailma [The world of meanings] . 2000; Tampere: Vastapaino.

- Lyons C. V., O'Connor F. Constructing an integrated model of the nature of challenging behaviour: a starting point for intervention. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties. 2006; 11(3): 217–232.

- Mallory B., New R. Social constructivist theory and principles of inclusion. challenges for early childhood special education. Journal of Special Education. 1994; 28(3): 322–338.

- Marcos J. J., Miguel E. S., Tillema H. Teacher reflection on action: what is said (in research) and what is done (in teaching). Reflective Practice. 2009; 10(2): 191–204.

- Mesman J., Koot H. M. Early preschool predictors of preadolescent internalizing and externalizing DSM-IV diagnoses. JAMA. 2001; 40: 1029–1036.

- Mietola R., Lappalainen S. Kiilakoski T., Tomperi T., Vuorikoski M. ‘Hullunkurisia perheitä’. Perheen saamat merkitykset kasvatuksen kentällä [‘Funny families’. Meanings of family in educational field]. Kenen kasvatus? Kriittinen kasvatus ja toisin kasvatuksen mahdollisuus [Whose education? Critical education and the chance to educate differently] . 2005; Jyväskylä: Vastapaino. 112–135.

- Morgan P., Farkas G., Qiong W. Kindergarten predictors of recurring externalizing and internalizing psychopatholoy in the third and fifth grades. Journal of Emotional & Behavioural Disorders. 2009; 17(2): 67–79.

- Ojala M. IEA Preprimary Study in Finland 3. How parents and teachers express their educational expectations for developing and teaching young children. 1997; University of Joensuu. Faculty of Education.

- Oliver C., McClintock K., Hall S., Smith M., Dagnan D., Stenfert-Kroese B. Assessing the severity of challenging behaviour: psychometric properties of the challenging behaviour interview. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2003; 16(1): 53–61.

- Oliver M. Understanding disability: from theory to practice. 1996; Basingstoke: Macmillan.

- Oliver R. M., Wehby J. H., Reschly D. J. Teacher classroom management practices: effects on disruptive or aggressive student behavior. Society for Research on Educational Effectiveness. 2011. http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED519160 (Accessed 2014-10-10).

- Papatheodorou T. Behaviour problems in the early years: a guide for understanding and support. 2005; London: Routledge Falmer.

- Pihlaja P. Päivähoidon syrjällä – erityispäivähoito Suomessa 1997 [On the edge of day care – special day care] . 1998; Helsinki: The Ministry of Social and Health Services.

- Pihlaja P. Varhaiserityiskasvatus suomalaisessa päivähoidossa [Early childhood special education in Finland] . 2003; University of Turku. PhD diss.

- Pihlaja P. Behave yourself! – examining meanings of children with socio-emotional difficulties. Disability & Society. 2008; 23(1): 5–15.

- Pihlaja P. Erityisen tuen käytännöt varhaiskasvatuksessa – näkökulmana inkluusio [Early childhood special education practices: the view of inclusion]. Kasvatus. 2009; 49(2): 42–53.

- Pihlaja P. Silvennoinen H., Pihlaja P. Susta ei tuu koskaan mitään. Sosiaalisemotionaalisten vaikeuksien näyttämöllä [You will never be something: the scene of social-emotional difficulties in basic education]. Rajankäyntejä. Tutkimuksia normaaliuden, erilaisuuden ja poikkeavuuden tulkinnoista ja määrittelyistä [Between the lines. Studies about interpretations and definitions of normality, difference and deviance] . 2012; Turku: Turun yliopiston kasvatustieteiden tiedekunnan julkaisuja A. 319–343. 214.

- Pihlaja P., Rantanen M.-L., Sonne V. Varhaiserityiskasvatus Varsinais-Suomessa. vastauksia monitahoarvioinnilla [Early childhood special education in South-Western Finland] . 2010; Turku: Varsinais-Suomen sosiaalialan osaamiskeskus.

- Pihlaja P., Holst T. How reflective are teachers? A study of kindergarten teachers’ and special teachers’ levels of reflection in day care. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research. 2013; 57(2): 182–198.

- Powell D., Fixsen D., Dunlap G., Smith B., Fox L. A synthesis of knowledge relevant to pathways of service delivery for young children with or at risk of challenging behavior. Journal of Early Intervention. 2007; 29(81): 81–106.

- QSR International. 2014. http://www.qsrinternational.com/products_nvivo.aspx (Accessed 2013).

- Reindal S. M. Discussing disability. An investigation into theories of disability. European Journal of Special Needs Education. 1995; 10(1): 58–69.

- Ryan J. Uncovering the hidden voice: can Grounded Theory capture the views of a minority group?. Qualitative Research. 2014; 14(5): 549–566.

- Scanlon G., Barnes-Holmes Y. Changing attitudes: supporting teachers in effectively including students with emotional and behavioural difficulties in mainstream education. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties. 2013; 18(4): 374–395.

- Seppovaara R. Kerran tarkkislainen – aina tarkkilaislainen [Once maladjusted - always maladjusted?] . 1998; University of Helsinki. PhD diss.

- Sjöberg L. The constructing of the ideal pupil – teacher training as a discursive and governing practice. Education Inquiry. 2014; 5(4): 517–533.

- Snell M. E., Berlin R. A., Voorhees M. D., Stanton-Chapman T. L., Hadden S. Survey of preschool staff concerning problem behaviour and its prevention in head start classroom. Journal of Positive Behaviour Interventions. 2012; 14(2): 98–107.

- Sourander A., Haavisto A., Ronning J. A., Multimäki P., Parkkola K., Santalahti P., Nikolakaros G., Helenius H., Moilanen I., Tamminen T., Piha J., Kumpulainen K., Almqvist F. Recognition of psychiatric disorders, and self-perceived problems. A follow-up study from age 8 to age 18. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005; 46(10): 1124–1134.

- Sourander A., Klomek A. B., Niemelä S., Haavisto A., Gyllenberg D., Helenius H., Sillanmäki L., Ristkari T., Kumpulainen K., Tamminen T., Moilanen I., Piha J., Almqvist F., Gould M. Childhood predictors of completed and severe suicide attempts: findings from the Finnish 1981 birth cohort study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009; 66(4): 398–406.

- Strauss A., Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research. Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 1996; Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Strain P. S., Lambert D., Kerr M. M., Stragg V., Lenker D. Naturalistic assessment of children's compliance to teacher's requests and consequences for compliance. Journal of Applied Behaviour Analysis. 1983; 16: 243–249.

- SVT. Suomen virallinen tilasto. Erityisopetus [The official statistics of Finland. Special education] . 2012. http://www.stat.fi/til/erop/index.html (Accessed 2013-12-13).

- THL. Lasten päivähoito 2011 [Children's day care in 2011]. 2011; National Institute for Health and Welfare. http://www.julkari.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/102985/Tr30_12.pdf?sequence=4 (Accessed 2014-05-05)..

- THL. Lasten päivähoito 2013 [Children's day care in 2013]. 2014; National Institute for Health and Welfare. https://www.julkari.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/125389/Tr33_14.pdf?sequence=2 (Accessed 2014-12-10)..

- Thomas G. Clough P., Garder P., Pardeck J. T., Yuen F. What do we mean by ‘EBD’? In Handbook of Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties. 2005; SAGE Publications Ltd. 59–82.

- Thomas G., Loxley A. Deconstructing special education and constructing inclusion. 2002; Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Thornberg R. Informed Grounded Theory. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research. 2012; 56(3): 243–259.

- Tremblay R. E. The development of aggressive behavior during childhood: what have we learned in the past century?. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2000; 24: 129–141.

- Vehmas S. Vammaisuus: Johdatus historiaan, teoriaan ja etiikkaan [Disability: Introduction to history, theory and ethics]. 2005; Jyväskylä: Gaudeamus.

- Vehkakoski T. Leimattu lapsuus? Vammaisuuden rakentuminen ammatti-ihmisten puheessa ja teksteissä [Stigmatized childhood? Constructing disability in professional talk and texts]. 2006; University of Jyväskylä. PhD diss.

- Viitala R. Integraatio ja sen toimivuus lastentarhanopettajien arvioimana [Integration and its functionality assessed by kindergarten teachers]. 2000; Jyväskylä: Jyväskylän yliopisto. Research reports. Department of Special Education, University of Jyväskylä, no. 72.

- Viitala R. “Jotenki häiriöks”. Etnografinen tutkimus sosioemotionaalista erityistukea saavista lapsista päiväkotiryhmässä [Somehow difficult. 2014; University of Jyväksylä. An ethnographic study of children with special socio-emotional needs in a day care group]. PhD diss.

- Wright A-M. Every child matters: discourse of challenging behaviour. Pastoral Care in Education: An International Journal of Personal Social and Emotional Development. 2009; 27(4): 279–290.