Abstract

We trace the recent development of the Oxford Education Deanery as an expansion of an initial teacher education partnership to include wider school-university collaboration in professional development, and in research. The current policy pressures in England are described on both school-university partnerships for initial teacher education, and on schools and universities generally. Then, using cultural historical theory, we show the recent development of a complex alliance through shared understandings of motives, which created common knowledge expressed within a common narrative. We argue that such re-imagined school-university partnerships offer an optimistic future for teacher education.

Introduction

In many countries a close relationship between schools and universities in initial teacher education (ITE) is valued highly, leading to a plethora of research to describe, interpret and improve what are often called ‘school–university partnerships’. These partnerships come in many forms so some commentators have produced models or typologies of the different purposes and arrangements (e.g. Brisard et al. Citation2005; Callahan and Martin Citation2007; Furlong et al. Citation2000; Moran et al. Citation2009), while others have analysed the differences, and potential mismatches, between schools’ and universities’ understandings of their respective roles (Bartholomew and Sandholtz Citation2009; Ellis Citation2010; Smagorinsky et al. Citation2004). Some suggest that negotiating different contexts could be enriching (Tsui and Law Citation2007, Waitoller and Kozleski Citation2013), although others have argued for a clear shared agenda (Allexsaht-Snider et al. Citation1995): often at issue are different visions of what teaching involves both between different partnerships and within them.

All of this research is now given an added edge as the value of school-university partnerships is questioned, as some countries and jurisdictions look to alternative models of teacher education that require little, if any, university involvement, notably the USA (Chubb Citation2012) and England (Allen et al. Citation2014). This move has led those who value partnership to argue for deeper or new relationships (e.g. Cuenca et al. Citation2011; Waitoller and Kozleski Citation2013; Zeichner Citation2014). In this paper, we set out a case study of the first steps in such a reconceptualisation, in the Oxford Education Deanery (henceforth the Deanery) between 2010 and the present. Essentially, the Deanery is an expansion of an existing strong ITE partnership to include other school-university collaborations in continuing professional development (CPD), school development, and research in schools; it encourages more university involvement in local schools, and its particular contribution to new ways of aiding the development of student teachers has been described elsewhere (Childs et al. Citation2013; Edwards Citation2014). Here we first tell its story both in the history of ITE at Oxford and in the changing policy landscape, before showing the nature and significance of narrative in its emergence.

Teacher education began at the University of Oxford in 1892 with the University Day Training College. In 1919 the University Department for the Training of Teachers was established, later becoming the current Oxford University Department of Education (OUDE). OUDE's more recent history has embraced both the Oxford Internship Scheme, an ITE programme for secondary school teachers based on a deep partnership with local schools (Benton, Citation1990; Hagger and McIntyre Citation2006; McIntyre Citation2009; also see Ellis Citation2010), and a strong international research profile in areas including teacher education, subject knowledge for teaching, and pedagogy. The Oxford Internship Scheme was introduced in 1987 and was a precursor to the current partnership models of ITE in England and Wales.

Currently, the Department has also demonstrated high standards in educational research by being ranked first in the United Kingdom's 2014 Research Excellence Framework, further consolidating its position from the previous national review in 2010. The 2014 grades were based on a submission of 85% of staff, showing that there is not the research divide that is found in some English universities between teacher education and other staff. The developments to be discussed therefore build on a long history of university involvement in ITE, almost 30 years of close collaboration with schools in the preparation of beginning teachers, the emergence of OUDE as a major contributor to educational research internationally, and the strong involvement in research of staff working in teacher education.

In early 2010, the landscape of ITE provision in England was already complex, with an array of routes towards qualification as a teacher, but the policy context was not the original driver of the innovation. Instead, the Deanery built on much earlier proposals that stronger institutional links within ITE partnerships would benefit student teachers by offering them greater consistency of support when they moved between university and school (Edwards et al. Citation1996). These ideas were augmented by more recent understandings of how different specialist expertise is distributed in and across systems, and how that expertise can be brought to bear on complex tasks (Edwards Citation2010, Citation2011, Citation2012).

In February 2010, the Deanery was first discussed with headteachers as a multi-layered system of distributed expertise in which the three layers were ITE, CPD and research: these headteachers immediately recognised its potential. Three months later, the Westminster government changed to the Conservative-led Coalition, and the subsequent policy shifts had implications for the embryonic Deanery; for example, there was an immediate emphasis on schools’ role in ITE, and research-oriented universities were pressured to demonstrate greater efforts to attract pupils from lower socio-economic backgrounds. After almost four years of discussion between headteachers and other school leaders, OUDE staff, and other university staff, the Deanery was officially launched in November 2013. It is a partnership between the University and seven members of an existing alliance – Oxford City Learning (OCL) – comprising all state secondary schools in Oxford. Membership was not fixed, with the intention of strategically extending it over time. The term ‘Deanery’ has an ecclesiastical root, as a group of parishes working together, but here echoed its previous use in a medical context – the Oxford Medical Deanery – to describe regional university-linked postgraduate education networks for staff working in health services.

Here we draw on research undertaken between 2012 and 2014 which elicited the motives of different participants in the Education Deanery. Data analysis was premised on the explanation of the Deanery as a site of intersecting, but different, practices, each reflecting the specialist expertise it offers to local education. The analytic focuses were: (i) following cultural historical understandings of motivated action, the different motives shaping participants’ engagement with the emerging Deanery; and (ii) drawing on narrative theory, how these motives have been brought together to create the common narrative that gives direction to the Deanery as it continues to develop.

The English policy environment

The steady trajectory from the 1970s of neo-liberalism across all sectors of English education is now very apparent, with the increasing ‘marketisation’ of schooling and higher education, alongside growing emphasis on ‘performativity’ for schools and teachers (Gleeson and Husbands, Citation2001). Education policy in England under the Coalition Government between 2010 and 2015 overtly weakened the role of local government in guiding local schools and instead strongly encouraged state-funded schools to operate outside local education authority structures, and be directly responsible to central government. Local educational authorities were considered overly bureaucratic and inherently Leftist, and this encouragement has enabled chains of autonomous schools to emerge and expand, both superseding local structures and eroding traditional divisions between private and public education in another neo-liberal development. A major change in Higher Education since the 1970s, alongside an expansion of the sector, is the charging of fees, with the result that student debt is now a concern for many potential applicants. Policy discourses, however, now embrace the needs of disadvantaged learners and are played out through the language of ‘Closing the [attainment] Gap’ in schools, and of ‘widening participation’ in higher education.

In relatively high status universities like Oxford these developments have a particular purchase. For example, when OUDE and schools were working towards establishing the Deanery during 2010, the University of Oxford was being encouraged by the government to set up its own school, perhaps a University Training School as part of a national effort to ‘close the gap’. The University instead chose to support the Deanery initiative to enhance the relationship between the wider university and local schools more generally, and strategically strengthening the University's local links across all areas of academic activity. The historical ties between OUDE and 30 or so local secondary schools through the PGCE partnership were recognised as a valuable element in this broadening portfolio, while the Deanery was a way of demonstrating commitment to this endeavour. Recent public statements by Oxford's Vice-Chancellor reflect how the Deanery links with university strategy on connecting with local schooling:

We believe that our education expertise should be available to children across our city, regardless of ability or background. For all its success, this is not something the academy model can readily deliver. For that reason, there is no Oxford University Academy but rather a broader, more inclusive initiative, the Oxford Education Deanery (Hamilton Citation2014, 63).

He then particularly highlighted how “it promotes collaboration among schools, rather than competition between them” (ibid.). Consequently, while the Deanery is not a substitute for a local education authority, it can help mediate the local implementation of national policies, giving schools research-informed room for manoeuvre.

At the same time, the University was responding to the national Office for Fair Access’ [OFFA] expectations for widening access, i.e. that universities should actively encourage a more diverse socio-economic and ethnic range of school pupils to both aspire to university and to apply. The University has developed a two-stranded strategy. First, ‘Increasing Access’ is intended to ensure that pupils from diverse backgrounds across the United Kingdom apply to Oxford, and is aimed at 16- to 18-year-old pupils. The Increasing Access initiative has begun to bear fruit. For instance, between 2008 and 2014 the percentage of pupils from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds rose from 5.6% to 9.3% (University of Oxford Citation2015); however, this is still far below the current national figure of 20.7% (OFFA Citation2014, 32). Second, ‘Widening Participation’ is aimed at encouraging pupils aged 9–16 in local schools to consider the value of higher education generally, not just Oxford. Members of the university Widening Participation team at Oxford have been major contributors to the Deanery's development as the Deanery's aims connect with the University's ambitions (Alexander et al. Citation2014). The Vice-Chancellor illustrated this role:

Most vitally, [the Deanery] aims to raise the aspirations of a community of local secondary school students. It's so much easier to dream when you know other kids across your region share those dreams (Hamilton Citation2014, 63).

Over the same period, ITE has been subject to ever increasing government control in England. Childs and Menter (Citation2013) traced how, since 1984, Westminster's control of the structure and content of English ITE has increased, with a simultaneous diversification of routes into teaching. The post-2010 Government sought explicitly to create a school-led system of ITE in which universities play a much reduced role. Most significantly, the array of school-led routes was augmented in 2012 by the introduction of School Direct, which includes an employment-based route known as “School Direct (Salaried)”; these routes are led by schools which are allocated student numbers that are taken from the allocation previously given directly to universities. Some Vice-Chancellors in England are therefore questioning the viability of teacher education provision. For research-intensive universities, these uncertainties have increased because of the challenges in generating excellent research alongside time-consuming professional education work. Some universities have withdrawn from ITE and others are considering their position; for example, one has placed ITE in a separate business unit with no significant research expectations of staff. Paradoxically, these threats to university involvement in ITE in England run counter to trends elsewhere, both within the UK more broadly (Beauchamp et al. Citation2013) and internationally (Tatto, Citation2013). The upshot for ITE in English universities is that a rationale for involvement needs to be articulated with even greater clarity.

Schools have also been experiencing policy-led shifts in relation to CPD and research. Under the Labour government which ended in 2010, schools were encouraged to collaborate, and all City of Oxford state-funded secondary schools had by then linked themselves to form OCL which, as already indicated, became a key partner in the Deanery. The City of Oxford includes areas with high levels of deprivation where raising disadvantaged pupils’ attainment and aspiration has been a struggle for many of these schools, with examination results consistently below the national average. Consequently, the schools began to work together, sharing resources and building pedagogical expertise specifically focused on these needs. Further, under the Coalition government, individual schools or groups of schools could bid to be designated as a “Teaching School” in order to lead alliances of local schools to work on six “Big Ideas”, including Initial Teacher Training and Research and Development. Three Oxfordshire schools, including one city school, were designated as “Teaching Schools” in 2013, establishing a countywide alliance – the Oxfordshire Teaching School Alliance (OTSA) – which has also become significant in the Deanery's development. Research, including the government's preferred methodology of randomised controlled trials (Goldacre, Citation2013), is now part of schools’ agenda and the Deanery offers support for research engagement, including mediating research findings, undertaking action research projects and contributing to major joint research projects (e.g. Childs et al. Citation2013).

The policy churn indicated in this brief overview has meant that all three groups, OUDE, schools and university strategists have developed motives for engagement which reflect both their distinct historical expertise and also their need to address new demands. Next, we explain how we have conceptualised these motives before moving to trace the interweaving of motives in the emergent common narrative within the Deanery.

Building common knowledge at a site of intersecting practices

While we are familiar with the notion of inter-professional working between, for example, teachers and educational psychologists (Leadbetter Citation2008) or teachers and welfare professionals (Edwards et al. Citation2009; Edwards et al. Citation2010; Glenny and Roaf Citation2008), relationships between the university-based and school-based elements in ITE have only just begun to be thought of in this way (e.g. Waitoller and Kozleski Citation2013). Instead, we in ITE have previously spoken of partnership as an important principle, but in ways which have tended to obfuscate the different strengths that each practice brings to the formation of professionals.

Central to our analysis is the idea of a practice as being “[h]istorically accumulated, knowledge-laden, emotionally freighted and given direction by what is valued by those who inhabit [it]” (Edwards Citation2010, 7). This definition draws on cultural-historical analyses of institutional practices, which pay attention to the motives that shape them, and particularly to the continuous dialectic between personal and institutional motives as practices are taken forward. A key cultural-historical concept is “object motive”, which comes from Leont'ev – a close colleague of Vygotsky in late 1920s’ Moscow. Leont'ev's idea of “object motive” (Leont'ev Citation1978) is a very different view of motive from that in most psychology texts. Examining activities and how individuals interpret what is important in them, he talked of the “object of activity” as the focus of collaborative activity: in ITE an object of activity might be a beginning teacher's learning trajectory. Obviously, in supporting that trajectory the different partners may see it differently: a headteacher might interpret an averagely performing physics student teacher as a good potential employee, while the student's university PGCE tutor might see her as needing additional challenges. Each interprets the trajectory, employing concepts that matter to them and engages with the object of activity in ways that reflect his or her interpretation. Leont'ev described this phenomenon as the “object motive”: our motives are reflected in the interpretations we make of the object of activity and our engagement with it.

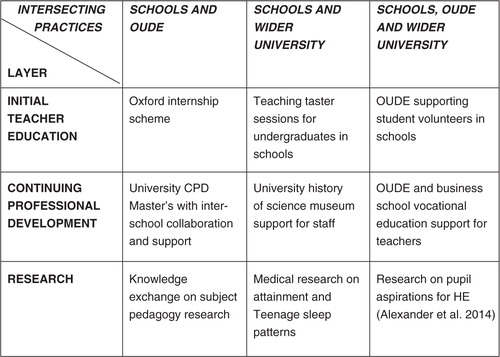

The idea of object motive was used by a Deanery co-ordinating group to conceptualise the Deanery itself as an object of activity which has been jointly constructed and where all needed to recognise the different object-motives or ‘what matters’ for each participant. Over four years, the Deanery was therefore interpreted and engaged with by inhabitants of different practices, who have brought their own object motives to bear in the activities that are forming it. Examples of potential collaborative activities are shown in , as participants have collaborated in three broad combinations: schools and OUDE; schools and the wider university; and schools, OUDE and the wider university.

simply indicates activities in separate layers (ITE, CPD and research) and does not capture the combining of layers, for instance how placing several student teachers in one department to carry out classroom research during teaching practice also provided opportunities for CPD and research (Childs et al. Citation2013).

The Deanery's emphasis on the object motive for each practice originates in Edwards’ work on the building of common knowledge as a resource for collaboration (Edwards Citation2010, Citation2011, Citation2012). Common knowledge is described there as consisting of a shared understanding of the motives, the ‘what matters’, for each participating practice. This common knowledge is built up over time to become a lasting resource that can be deployed to help collaboration on complex tasks, such as supporting the learning trajectory of student teachers. Seeing ITE collaboration in this way, for example, shifts attention from seeing the student teacher as a boundary-crosser negotiating her learning trajectory between the different practices of university and school (see Tsui and Law Citation2007; Waitoller and Koslezki Citation2013); instead, the focus is her trajectory and how it might be supported by all participants. Similarly, the problem of supporting young vulnerable learners in schools becomes a topic worked on jointly by both schools and university-based researchers (Stamou et al. Citation2014). The Deanery has therefore developed to enable the expertise distributed across the University and local schools to be brought together to work on complex educational objects of activity. It is a site where participants have developed and deployed ‘common knowledge’.

This conceptualisation of common knowledge was previously used to examine how successful Directors of Children's Services (DCSs) aligned the different motives of the various professions that they led (Daniels and Edwards Citation2012), and was discussed in terms of how DCSs create and deploy organisational narratives (Edwards and Thompson Citation2013). That study revealed how expertly DCSs built narratives which recognised and aligned different professions’ object motives and then used those narratives, consisting of common knowledge, to take their strategic aims forward. Within the Deanery, common knowledge has been built up over time in meetings, discussions and activities and then captured in a set of principles, which remained open to scrutiny and change: it has become a resource that is used to mediate negotiations about the future of the Deanery.

The Deanery therefore was explicitly developed using cultural historical theory. In the study reported here, we focus on how different object motives were made evident in discussions, and then brought together in a co-authored narrative to be used as a mediating resource or ‘tool’ (Wertsch Citation2002) and what Holland et al., from a more practice-oriented perspective, described as “a quieter means of social reconstitution” (Holland et al. Citation1998, 253). Therefore, echoing Bruner (Citation1990, 52) who argued that narrative meaning is based on “human action and human intentionality”, we consider how the development and use of a narrative, which brought together participants’ different motives, supported the Deanery's strategic development and how the demands made by policy shifts contextualised the creation and deployment of the narrative.

Methodology and methods

As researchers working on teacher education and professional development, we have recorded the development of the Deanery as a unique case study since 2010. In the analysis reported here we focus on the period between 2012 and 2014 in which we gathered interview data from key participants in the formation of the Deanery. When reflecting on these data it became clear that the Deanery narrative which emerged was being used as a resource for creative collaborations, such as a programme for newly qualified teachers (NQT) which drew on the strengths of both OCL and OUDE. In attempting to reveal the process of narrative construction and its use over time, we returned to the interview data and other documentation to interrogate them using the following three research questions, which are informed by the cultural historical precepts just outlined:

What were the object motives of the different participants during the Deanery's emergence? This question recognises the importance of identifying individuals’ accounts of what is important in their practices, an approach with a long history in research on student teachers (e.g. Clandinin Citation2007; Doecke et al. Citation2000; O'Neill et al. Citation2009).

How did the common narrative emerge? This question focuses on the co-construction of narratives and their dialogicality (Bakhtin Citation1981; Wertsch Citation2002), shifting from narratives of motives within discrete practices to the construction of a common narrative, encompassing and shaping the ‘what matters’ in each contributing practice (Holland et al. Citation1998). This approach echoes narrative enquiry in organisations (e.g. Czarniawska Citation2007). Here we focus on how the Deanery came into being through the production and deployment of narrative, rather than on narratives within existing organisations.

How might that narrative support strategic development? We lastly consider the narrative's role as a tool to develop the Deanery, focusing particularly on its internal dialogicality as a process of collective co-authoring by participants across practices and on how the common narrative was shared and collectively authored around new opportunities.

Two data sources were used. First, semi-structured interviews shaped by cultural historical theory were employed to capture participants’ motives, allowing participants to contribute personal narratives of their engagement with the idea of the Deanery. Sixteen interviews took place: three were with pairs and the remainder with individuals. One respondent was interviewed twice, in a pair and individually; there were 18 participants in total. These data addressed the first and second research questions. The three authors carried out the interviews with respondents who were purposively selected from specific categories of stakeholders.

The interviews were in two phases. Early in 2012, we interviewed: one headteacher individually; two pairs of a headteacher and a senior leader; one pair of two senior leaders; five OUDE staff individually; two staff from the university administration; one representative of a student volunteer group which worked with schools, the Student Hub. Subsequently, in early 2014, two senior school leaders and the OCL co-ordinator were selected because of their roles within the Deanery to explore their interpretations of the developing narrative; one of them had taken part in a joint interview in 2012.

All interviews were recorded and all but two were fully transcribed (there were sound problems with these two exceptions, although detailed notes had been taken by a research student during these meetings). The second dataset comprised all the Deanery documents, notably meeting minutes, and the series of drafts leading to the formal Memorandum of Agreement (MoA) that now underpins involvement in the Deanery; this dataset provided a means of establishing how the common narrative was more formally scripted and for triangulating this analysis with the interviews (Denzin Citation1997). As authentic documents, they also revealed narrative shifts over time.

All research was conducted within BERA's ethical guidelines (BERA Citation2011) and approved under the University's research ethics procedure. However, the case is specific and the participants were therefore potentially identifiable; they were aware of this. They also knew that we were both researchers and involved in the Deanery's development. Data were analysed both deductively, with a focus on motives in practices and the development and use of the narrative as a resource, and inductively, being responsive to emerging themes. The first author carried out the analysis after discussion with the other authors, and emergent interpretations were triangulated against independent analyses of the data samples (Denzin Citation1997).

Findings

Participants’ Motives

To answer the first research question, we reveal the dominant object motives of practitioners within practices in schools, OUDE and the wider university in relation to the emergent Deanery, recognising that the participants were not formal representatives of practices, but talked about the activities the Deanery might offer in terms of what mattered to them.

School leaders’ motives related to: professional development; evidence of effectiveness of school approaches; using and sharing research in schools; and teacher retention. For example,

We weren't able to recruit the quality of people perhaps that we wanted, and we had difficulty in attracting people to apply (Headteacher 2012).

They were particularly concerned about pupil attainment, and aspiration:

We can do the grades. We can now get A's in every subject in this school, which wasn't the case before. It was … very different. But I don't think you can build up [the] confidence [to apply to leading universities] in the 6 th form – that has got to be earlier (School leader 2012).

They also recognised the different object motives within their school:

We've been working at school on thinking really that sometimes teachers think that a magic solution like going to an INSET … is really going to solve it for them, and it isn't really, it's the work that they do … It's like practising piano, isn't it? It's not the lessons; it's the practice in between (Headteacher 2012).

OUDE teacher educators outlined different object-motives. ITE policy concerned them, but their motives were frequently related to their pedagogical roles:

… turning personal subject knowledge into subject-specific pedagogic knowledge, and helping others to do the same (OUDE staff 2012).

They also were keen to develop the role of schools in research:

I've always wanted the relationship to be two-way so that [schools] should always be involved in any research bid … by [OUDE] (OUDE staff 2012).

However, they recognised that there were different ways of working with schools:

I've always believed strongly that we should be thinking of multi-level partnerships not single level partnerships, and the opportunity to bring that together … would be valuable. (OUDE staff 2012).

I'd like to see some of the young people coming in here more – I've seen it done well by MFL [Modern Foreign Languages] on the [ITE programme], where they invite 6th formers into [OUDE] (OUDE staff 2012).

Other University respondents had different motives. The Widening Participation team wanted to reach local schools more effectively. As already indicated, the University had been encouraged by the Government to sponsor a local academy or establish a training school, which had raised concerns:

I talk to my colleagues at other universities. They're all facing this ‘academy problem’ … but [I] sure would like to be promoting a different, more imaginative and in my view much more impactful model (University administrator 2012).

The Student Hub representative wanted advice on supporting student volunteers in schools:

And one thing that it would be really useful for us to be able to think through with other partners in the Deanery is: what is the most effective way to use students? (Hub coordinator 2012).

When individuals and organisations came to understand each other's motives, they built up common knowledge. This process was often through recognising complementary commonalities in each other's object motives, for instance a school leader recognising a wider shared sense of responsibility with the University for pupils’ education:

I think it ties in with both organisations’ objectives in terms of a sort of collective responsibility for the people within the city and looking at how we can harness that (OCL co-ordinator 2014).

Respondents could imagine how commonalities between different participants could be productive, for instance ITE generating departmental CPD:

It's … definitely true that if you are a teacher working with a student teacher you look at what you are doing in a different way … If you put six student teachers in a department with six teachers, you work on ideas together and reflect on what you are doing as a department. It's fantastic CPD (OUDE staff 2012).

However, respondents could also recognise commonalities between other potential stakeholders within the Deanery:

I suspect that what's at the core from [OUDE's] point of view in the first stages is actually professional learning, i.e. the learning of teachers, but it's trying to connect with other relationships between the University and the schools (University administrator 2012).

Participants also identified the benefits accruing to other participants through engagement with the Deanery. For instance, one OUDE staff member pointed to how the Deanery helped the University tackle its elitist reputation:

The University as a whole has been criticised for its elitism … but then being involved [in the Deanery] is one way of addressing that (OUDE staff 2012).

Interview questions also revealed sensitivity to conflicting object-motives within institutions, such as between the practices of school leadership and classroom teaching. The Student Hub respondent wanted to place Oxford students alongside pupils but, as she explained:

The headteacher will say, ‘It's a great idea, get in touch with all the heads of department and place your volunteers’. And then you go down to the teacher level and they're like, ‘Oh, I'm a bit too busy for this’. And so on a very practical level, on a workload level even, like, what are the main kind of drawbacks to having volunteers? (Hub coordinator 2012).

These examples, based on discussions of practices and the motives that shaped them, begin to indicate the vast array of reasons for engaging with the Deanery. Common knowledge therefore needed to be framed in a way that reflected the intentions and motives of all potential participants.

How the Deanery Narrative Has Been Built

It is unusual to have the opportunity to examine how a common narrative emerges, and particularly striking was how it was constantly open to being refined and augmented to reflect changing motives and new practices, akin to the process of “making alternative worlds” (Holland et al. Citation1998, 253). This development can be seen to draw on some classic narratological elements. Narratives typically contain significant referential features, notably settings, characters and events (Wertsch Citation2002, 57), and the MoA between the university and individual schools exemplifies them. It presents a set of collective principles in which each institution can identify both their own priorities and those of others, and was the outcome of collective re-drafting, for example:

As partners in the Education Deanery we are committed to: investment in the future of the teaching profession; doing high quality research that is relevant has relevance and significance for the future of the profession … achieving a positive, measurable impact on the learning outcomes of pupils in local schools, including impact on widening participation in Higher Education; creating strong learning environments; adopting a constructive and critical approach to curriculum development and assessment (Draft December 2013, showing changes).

This new wording reflects both schools’ concerns about research that will affect pupils’ attainment, as well as the University's concerns about widening participation.

Identifying characters with motives is fundamental to both fictional and factual narratives (Burke Citation1945; Jannidis Citation2012). Part of our argument is that the development of the Deanery created a discursive space in which other people's motives could surface, and when participants started talking about motives, ‘characters’ emerged. The Student Hub worker's comments at the end of the previous section are an example of this characterisation process. She devised a script, through a “living hermeneutics” (Bakhtin Citation1981, 338), for the headteacher and the classroom teacher, and a dramatic narrative vignette is enacted, in which she showed how her own object-motives are thwarted. The quotation marks was added in the transcription, but could nevertheless be metaphorically heard in the interview, in the shift in pronouns. Further, by surfacing others’ motives, individuals can start to develop episodes and events which express them:

The other issue I think is anything that the University can do in order to join up its messages and its opportunities would be amazing. I know having sat in various other meetings … teachers have said, ‘Well, we don't know who to go to sometimes for this, because it's this person for this, this person for that’ and I think it can be overwhelming for them (University Widening Participation Officer 2012).

In this case, the Deanery becomes a potential solution to a narrative about how others are thwarted by the University's internal complexity.

Its second narrative feature is “tellability”, i.e. that it is worth telling (Baroni Citation2012; Ochs and Capps Citation2001). As Bruner (Citation1990, 47) argued, “narrative … specialises in the forging of links between the exceptional and the ordinary”. Narratives can weave existing, taken-for-granted practices and motives into new ways of working – into new plots. Thus the MoA included the history of ITE in OUDE which, although known and therefore taken for granted, was not necessarily explicit:

The origins of the Deanery lie in … the exceptionally strong 25 year partnership that exists between [OUDE] and local schools … (MoA all drafts, 2012-14).

The story of earlier Deanery meetings followed, building the exceptional onto the ordinary:

Discussions between OUDE and colleagues in Oxfordshire Schools, about intensifying connections to build a system in which expertise could be shared and developed, started in February 2010 … (MoA final version 2014).

Finally, it becomes a common narrative because it allows participants to configure different characters and practices into an interpretable unity, as a story that organises, not the story of an organisation (Czarniawska and Gagliardi Citation2003).

It's about things hanging together – that you've got a place to put a number of individual elements and make them connect (Headteacher 2012).

But it also represents and sustains the emergence of a sense of trust and affiliation necessary for new work (Edwards and Kinti Citation2009), so both the MoA and several respondents employed a collective ‘we’:

I guess the Deanery I saw as an umbrella term … so it's kind of an umbrella grouping for us to work together (OCL Co-ordinator 2014) (emphasis added).

The common narrative is therefore built out of the common knowledge of each other's motives through the layering of motives with characters, embedded in an account of recent history and possible futures, which becomes a shared “figured world” of mutually understood practices (Holland et al. Citation1998, 49).

How the Narrative Supports Strategic Development

The narrative is not simply aetiological; it also serves as a “cultural tool” (Wertsch Citation2002, 55) to develop the Deanery; while Wertsch focused on narrative as a means for remembering the past, we focus here on its role in shaping the future, as a “living story” (Boje Citation2001):

You see at one level that's a very simple model which we can start tomorrow and grow from there (Headteacher 2012; emphasis added).

However, the interplay between the collective ‘we’ and common knowledge of others’ motives allowed new collaborations to be imagined, in what Bruner (Citation1996) called “possible worlds”. For example, a recent development was to work together to support a bid for knowledge exchange funding within the University

… focusing in particular on task design in secondary school subjects. This has been led by [OUDE staff]. [It has] been supported and endorsed by … OCL (Steering group report 2014).

Another possibility was with OTSA, the local teaching schools’ alliance. A Deanery report stated:

It has been proposed by [OTSA] that OUDE might take a lead in running an induction support scheme for secondary NQTs … Although this would not be limited to current membership of the Deanery, nevertheless it would be of benefit to these schools (Advisory meeting report 2014).

The benefit to the schools is clearly noted here, and in the meeting minutes the benefit to OUDE was also noted.

Another example was of individuals identifying particular groups in other organisations with whom they hoped to work. Here is an OUDE teacher educator:

I've always been interested in the way [school] departments work … and the ways that you can make a difference at a departmental level where you can't make it at a school level (OUDE staff 2012).

Yet, significantly, it was seen by most respondents as a resource through which policy initiatives might be filtered by an understanding of what matters for the intersecting practices in the Deanery:

It's about a kind of clarity of thinking where you can … identify a set of values and ideas, … that these are our very clear values and principles about learning … They operate almost independently of things like national policy and the political shifts and changes … If the politicians say we've got to do this, [we say] our values are this (Headteacher 2012).

The narrative was certainly not hierarchical in terms of the knowledge that mattered. School respondents had a strong sense of shared ownership, for example, seeing the narrative as vital for attracting new teachers to join:

For individual teachers to connect with what I hope is the big vision about the profession, research, pedagogy, practice, being excited by it, continually being reinvented and reinvigorated, actually giving them a narrative is something that they can realise, and then you can give it some examples (OCL co-ordinator 2014).

Moreover, the narrative would subsequently be shaped by these new participants, who would contribute to both their own professional development (Doecke et al. Citation2000) and the common narrative:

These professionals will be involved in that story, changing it, so they can help shape it (OCL co-ordinator 2014).

The participants, however, were not naive. They foresaw potential dangers: the lack of resourcing, time and staffing; the danger of initial teacher education “getting lost in lots of tentacles, in lots of pies” (OUDE staff 2012); the demands of increased involvement from university departments and colleges; and other and changing pressures on schools. They also accepted that not all proposed projects would materialise:

I'm not going to say it has to work instantly, and I'm prepared to … have a go and embrace failure (Senior school leader 2014).

The common narrative has therefore been significant in shaping the Deanery and has been shaped by the participants in it. Analysis of the two datasets has revealed quite powerfully the extent to which their motives were woven into a common narrative which operated as a discursive resource for the Deanery's development. We have therefore come to recognise deep-seated connections between basic narratological features, such as characterisation, and participants’ motives in the configuration of the narrative. The resulting narrative, while common in one sense, is also uncommon in another, in that its tellability allows previously unconnected practices to be linked, such as ITE and widening participation. The narrative has therefore operated as a tool allowing participants from different practices to develop new ideas together, responding to threats and opportunities. At the same time, they have augmented it through imagining and articulating developments to the narrative – new chapters, as it were. There is collaborative self-authoring, as through dialogue the participants worked on new opportunities and problems together, their collaboration mediated by the common knowledge embedded in the narrative. Less radical than the ‘alternative worlds’ of feminist protest in Nepal which Holland et al. (Citation1998) describe, it nevertheless shows how alternative ways of working can be configured.

Discussion: reimagining partnership

As we have already indicated, in jurisdictions where the involvement of universities in ITE is under threat, some argue that new conceptions of partnership are needed to address this growing scepticism (Moran et al. Citation2009; Waitoller and Kozleski Citation2013; Zeichner Citation2014). Indeed, countries with strong support for university involvement in ITE also seek to develop and improve these relations (Tatto Citation2013). We have set out a case study of a new conceptualisation of how school-university relationships came to be configured differently. In the Deanery, the position of ITE is strengthened because it is merely one layer within a wider set of intersecting practices. We have argued that, as part of that repositioning, an educationally-oriented narrative which reflects the expertise and motives of contributing practices can be a tool for collaboration across practice boundaries. Consequently, creating a common, yet mutable, narrative was seen as a worthwhile endeavour helping to anchor participants in what mattered for them in the midst of the extensive policy churn we have outlined. Ironically, for ITE, at a time when national policy aims to reduce university involvement in teacher education, the Deanery has expanded the ways that schools and universities collaborate.

A pragmatic question is whether a Deanery could be adopted or adapted elsewhere and by Departments which offer different research profiles. Indeed, the interviewees were optimistic: “it is a replicable model for other universities” (University Widening Participation Officer 2012). Clearly, aspects of this narrative are site-specific because of the particular institutional arrangements and motives involved. Nonetheless, there might be some for whom this account of intersecting practices could form an initial “template” (Wertsch Citation2002, 60) to work within their own setting; the contextual details set out above provide a point of comparison. Importantly, the Deanery was supported strategically by a university which felt that it had responsibilities towards local schools; but we have already observed that some other English universities have chosen to withdraw from ITE and engagement with schools. We would also like to emphasise that the Deanery was not a response to the policy churn we have outlined, but grew out of a long-standing ITE partnership and its emergence occurred slowly over four years of discussions which built common knowledge and wove the narrative. Nonetheless, underlying policy tensions still exist, and work continues on sustaining the Deanery as a site of intersecting practices, especially as the contradictory pressures on schools and universities are set to continue with a majority Conservative government now in place.

Should other groups like to use the approach we have outlined to create variations of the Deanery, we would wish to encourage attention to building a shared narrative comprising what matters in each contributing practice and to do so over time. Focusing on some basic narratological elements has aided us in identifying how the narrative allowed participants to get beyond simply sharing aspirations; it enabled them to build up mutual understandings, and indeed understandings of possible misunderstandings. Yet it also allowed them to re-imagine how they could collaborate more effectively by contributing differently, in new ways.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nigel Fancourt

Nigel Fancourt is a lecturer at the University of Oxford's Department of Education. He researches the relationships between schools and universities, and the relationships between religions and schools, and is a member of the Oxford Centre for Sociocultural and Activity Theory Research (OSAT). Email: [email protected]

Anne Edwards

Anne Edwards is Professor Emerita at the Oxford University Department of Education, where she was also recently Director of the Department and co-founder of the Oxford Centre for Sociocultural and Activity Theory Research (OSAT). She has written extensively on teacher education and professional learning. Email: [email protected]

Ian Menter

Ian Menter is Professor of Teacher Education and Director of Professional Programmes in the Department of Education at the University of Oxford. He was President of the British Educational Research Association from 2013–2015 and was previously the President of the Scottish Educational Research Association. Email: [email protected]

References

- Alexander P., Edwards A., Fancourt N., Menter I. Raising and sustaining aspiration in city schools. Research Report . 2014; Oxford: Department of Education, University of Oxford.

- Allen J., Belfield C., Greaves E., Sharp C., Walker M. The costs and benefits of different initial teacher training routes. 2014; London: Institute of Fiscal Studies.

- Allexsaht-Snider M., Deegan J., White C. Educational renewal in an alternative teacher education program: Evolution of a school-university partnership. Teaching and Teacher Education. 1995; 11(5Special Issue: Teacher Education Policies and Developments in Europe): 519–530.

- Bartholomew S., Sandholtz J. Competing views of teaching in a school–university partnership. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2009; 25(1Special Issue: Teacher Education Policies and Developments in Europe): 155–165.

- Bakhtin M. The dialogic imagination. 1981; Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Baroni R. Schönert J., Hühn P., Schmid W., Pier J. Tellability. Handbook of Narratology. 2012; Berlin: De Gruyter. 447–454.

- Beauchamp G., Clarke L., Hulme M., Murray J. Research and teacher education: the BERA-RSA inquiry. Policy and practice within the United Kingdom. 2013; London: BERA.

- Benton P. The Oxford Internship Scheme: integration and partnership in initial teacher education. 1990; London: Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

- BERA. Ethical guidelines for educational research. 2011; BERA: London.

- Boje D. Narrative methods for organizational and communication research. 2001; London: Sage.

- Brisard E., Menter I., Smith I. Models of partnership in programmes of initial teacher education. Systematic Literature Review commissioned by the General Teaching Council for Scotland, Research Publication No 2. 2005; Edinburgh: GTCS.

- Bruner J. Actual minds, possible worlds. 1996; Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bruner J. Acts of meaning. 1990; Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Burke K. A grammar of motives. 1945; New York: Prentice-Hall.

- Callahan J., Martin D. The spectrum of school–university partnerships: a typology of organizational learning systems. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2007; 23(2Special Issue: Teacher Education Policies and Developments in Europe): 136–145.

- Childs A., Edwards A., McNicholl J., McNamara O. et al . Developing a multi-layered system of distributed expertise: what does cultural historical theory bring to understandings of workplace learning in school-university partnerships?. Teacher Learning in the Workplace: Widening Perspectives on Practice and Policy. 2013; Dordecht: Springer. 29–45.

- Childs A., Menter I. Teacher education in the 21st Century in England: a case study in neo-liberal policy. Revista Espanola de Educacion Camparada [Spanish Journal of Comparative Education]. 2013; 22: 93–116.

- Chubb J. The best teachers in the world: why we don’t have them and how we could. 2012; , CA: Hoover Institute Press.

- Cuenca A., Schmeichel M., Butler B. M., Dinkelman T., Nichols J. R. Creating a ‘third space’ in student teaching: implications for the university supervisor's status as outsider. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2011; 27: 1068–1077.

- Czarniawska B. Clandinin J. Narrative inquiry in and about organizations. Handbook of Narrative Inquiry: Mapping a Methodology. 2007; Thousand Oaks: Sage. 383–404.

- Czarniawska B., Gagliardi P. Narratives we organise by. 2003; Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Clandinin J. Handbook of narrative inquiry: mapping a methodology. 2007; Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Daniels H., Edwards A. Leading for learning: how the intelligent leader builds capacity. 2012; Nottingham: National College for School Leadership.

- Denzin N. Keeves J. Triangulation in educational research. Educational Research, Methodology and Measurement: An International Handbook. 1997; Oxford: Elsevier.

- Doecke B., Brown J., Loughran J. Teacher talk: the role of story and anecdote in constructing professional knowledge for beginning teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2000; 16(3Special Issue: Teacher Education Policies and Developments in Europe): 335–348.

- Edwards A. Being an expert professional practitioner: the relational turn in expertise. 2010; Dordrecht: Springer.

- Edwards A. Building common knowledge at boundaries between professional practices. International Journal of Educational Research. 2011; 50(1Special Issue: Teacher Education Policies and Developments in Europe): 33–39.

- Edwards A. The role of common knowledge in achieving collaboration across practices. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction. 2012; 1(1Special Issue: Teacher Education Policies and Developments in Europe): 22–32.

- Edwards A. Ellis V., Orchard J. Learning from experience in teaching; a cultural historical critique. Learning Teaching from Experience: Multiple Perspectives, International Contexts. 2014; London: Bloomsbury. 47–61.

- Edwards A., Collison J. Mentoring and developing practice in primary schools. 1996; Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Edwards A., Daniels H., Gallagher T., Leadbetter J., Warmington P. Improving inter-professional collaborations: multi-agency working for children's wellbeing. 2009; London: Routledge.

- Edwards A., Kinti I. Daniels H., Edwards A., Engeström Y., Ludvigsen S. Working relationally at organisational boundaries: negotiating expertise and identity. Activity Theory in Practice: Promoting Learning across Boundaries and Agencies. 2009; London: Routledge. 126–139.

- Edwards A., Lunt I., Stamou E. Inter-professional work and expertise: new roles at the boundaries of schools. British Educational Research Journal. 2010; 36(1Special Issue: Teacher Education Policies and Developments in Europe): 27–45.

- Edwards A., Thompson M. Sannino A., Ellis V. Resourceful leadership: revealing the creativity of organizational leaders. Learning and Collective Creativity: Activity-theoretical and Sociocultural Studies. 2013; London: Routledge. 49–64.

- Ellis V. Impoverishing experience: the problem of teacher education in England. Journal of Education for Teaching. 2010; 36(1Special Issue: Teacher Education Policies and Developments in Europe): 105–120.

- Furlong J., Barton L., Miles S., Whiting C., Whitty G. Teacher education in transition: re-forming professionalism?. 2000; Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Gleeson D., Husbands C. The performing school. 2001; London: Routledge/Falmer.

- Glenny G., Roaf C. Multiprofessional communication: making systems work for children. 2008; Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Goldacre B. Building evidence into education. 2013. Available at http://media.education.gov.uk/assets/files/pdf/b/ben goldacre paper.pdf ((Accessed 2014-05-30)..

- Hagger H., McIntyre A. Learning teaching from teachers. 2006; Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Hamilton A. University of Oxford. 2014. Gazette Supplement (1) to 5072. Vol 145. http://www.ox.ac.uk/media/global/wwwoxacuk/localsites/gazette/documents/supplements2014-15/Oration_by_the_Vice-Chancellor_-_(1)_to_No_5072.pdf (Accessed 2015-01-05).

- Holland D., Lachicotte W., Skinner D., Cain C. Identity and agency in cultural worlds. 1998; Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Jannidis F. Schönert P., Hühn W., Schmid W., Pier J. Character. Handbook of Narratology. 2012; Berlin: De Gruyter. 14–29.

- Leadbetter J. Learning in and for interagency working: making links between practice development and structured reflection. Learning in Health and Social Care. 2008; 7(4Special Issue: Teacher Education Policies and Developments in Europe): 198–208.

- Leont'ev A. Activity, consciousness and personality. 1978; Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

- McIntyre A. The difficulties of inclusive pedagogy for initial teacher education and some thoughts on the way forward. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2009; 25(5Special Issue: Teacher Education Policies and Developments in Europe): 602–608.

- Moran A., Abbott L., Clarke L. Re-conceptualizing partnerships across the teacher education continuum. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2009; 25(7Special Issue: Teacher Education Policies and Developments in Europe): 951–958.

- Ochs E., Capps L. Living narrative: creating lives in everyday storytelling. 2001; Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Office for Fair Access. Annual report and accounts 2013–14. 2014; Bristol: OFFA. http://www.offa.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/HC-435-OFFA-annual-report-and-accounts-1314-rev.pdf (Accessed 2015-05-20).

- O'Neill J., Bourke R., Kearney A. Discourses of inclusion in initial teacher education: unravelling a New Zealand ‘number eight wire’ knot. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2009; 25(4Special Issue: Teacher Education Policies and Developments in Europe): 588–593.

- Research Excellence Framework. Results and submissions. 2014. http://www.ref.ac.uk/ (Accessed 2015-05-20).

- Smagorinsky P., Cook L., Moore C., Jackson A., Fry P. Tensions in learning to teach: accommodation and the development of a teaching identity. Journal of Teacher Education. 2004; 55(1Special Issue: Teacher Education Policies and Developments in Europe): 8–24.

- Stamou E., Edwards A., Daniels H., Ferguson L. Young people at risk of drop-out from education: recognising and responding to their needs. 2014; Oxford: Department of Education, University of Oxford.

- Tatto M. Research and teacher education: the BERA-RSA inquiry. The role of research in international policy and practice in teacher education. 2013; London: BERA.

- Tsui A., Law D. Learning as boundary-crossing in school–university partnership. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2007; 23(8Special Issue: Teacher Education Policies and Developments in Europe): 1289–1301.

- University of Oxford. Agreement with the Office for Fair Access 2015–16. 2015. http://www.offa.org.uk/agreements/University of Oxford.pdf (Accessed 2015-05-30).

- Waitoller F., Kozleski E. Working in boundary practices: identity development and learning in partnerships for inclusive education. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2013; 31(3Special Issue: Teacher Education Policies and Developments in Europe): 35–45.

- Wertsch J. Voices of collective remembering. 2002; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Zeichner K. The struggle for the soul of teaching and teacher education in the USA. Journal of Education for Teaching. 2014; 40(5Special Issue: Teacher Education Policies and Developments in Europe): 551–568.