Abstract

The paper explores the ways in which university-based Teacher Education Departments in Greece have operated to promote changes to their undergraduate curricula. Our research approach views these changes as responses to the policies of the European Union and the Bologna Process for the ‘modernisation’ of higher education systems across Europe. Data are drawn from qualitative analyses of 18 curricula in two periods of their development, the middle of the 1990s and the late 2000s. The analysis of the study is based on Bernstein's theoretical concepts of classification, framing and meaning orientations, and describes basic types of university curricula regarding content organisation, pedagogical practices of teaching and learning, and knowledge evaluation. The findings reveal that, along with the disciplinary and professional criteria for knowledge recontextualisation, which have traditionally been legitimate in the field of Teacher Education, forms of weakly classified knowledge systematically oriented to problem-solving professional practices and school effectiveness are gradually crystallising and tending to become dominant. We argue that the marked shifts in the pedagogical means of teacher education may run the risk of thinning out teachers’ knowledge base and de-professionalising their practices and identities.

Introduction

This paper presents and discusses the main reforms in Greek Teacher Education (TE) in the period from the 1990s up to the present, and analyses the gradually emerging forms of knowledge and pedagogical practices that are crystallising within the study programmes for the initial education and training of the future professionals of pre-school and primary education. A review of relevant Greek literature resources helped identify the upgrading of teacher education from its further education ‘College’ status (‘Pedagogical Academies’) to its university status in the 1980s as the crucial influence on the evolution of the field (Bouzakis et al. Citation1998). The other key factor affecting developments within this field has been the prolonged period it took the Departments of Education to establish themselves and win ‘proper’ recognition within the university sector (Stamelos Citation1999; Flouris Citation2010). The traces of these influences are still visible today in the structure and organisation of TE curricula, affecting the ways in which reforms are introduced (Flouris Citation2010; Sarakinioti Citation2012).

Moreover, in the post-Lisbon period, EU policies on Education and Training, the Bologna Process, and the related initiatives for national higher education and teacher training systems started being disseminated to member states (Eurydice Citation2002; European Union Citation2010; Piesanen and Välijärvi Citation2010). This is mainly through the Open Method of Coordination and funding programmes for regional development (Dale Citation2004; Alexiadou Citation2007; Zgaga Citation2013), such as implementation of the Operational Programme for Education and Initial Vocational Training II, 2000–2006 (OPEIVT II) in Greece (Flouris Citation2010; Gouvias Citation2007; Citation2011; Sarakinioti Citation2012).

Our analysis seeks to reveal and discuss the ways these three kinds of influence, namely the national upgrading, the institutional pace of change, and the European developments over time, are significant mediating factors in current responses of university education departments to global, European and national demands to ‘modernise’ their curricular and pedagogical practices. This is in order to satisfy international standards of quality and ensure that future teachers and other educational professionals are competent, productive and efficient in a globalised and competitive world.

Bernstein's theory on pedagogical discourse and the role of the three message systems of knowledge content, pedagogy and assessment (Bernstein Citation1971; Citation2000) inform our analysis of the main components of curriculum provision in TE, namely, the courses offered, the programme of students’ ‘practicum’ and the programme of dissertation writing, which in their interrelations realise the four-year undergraduate teacher education curricula. This particular theoretical approach allows us to describe the direction of curricular changes, understand the transformations in knowledge relations and reflect on the pedagogical context of initial education and training, where teachers first develop their identity as future professionals.

Teacher Education in Greece: ‘A brief history’

Greece belongs to those European countries which, in order to improve their educational results and the professional status of teachers, reformed teacher education in the decade 1975–1985 (Cowen Citation2002; Zgaga Citation2013). This kind of reform, wherever it occurred, had two main purposes: a) the institutional upgrading of teacher education; and b) the better quality of its content through the broadening of its academic base (Neave Citation1992).

Teacher Education in Greece entered the university sector in the early 1980s (Law 1268/1982; Gazette 320/1983). Education Departments (EDs) were institutionalised gradually in central and regional universities of the country and functioned alongside the ‘old’ Pedagogic Academies and Nursery Teachers’ Schools until 1991 (Presidential Decree 24/1991). Since then, TE has been operating within the legal framework of Greek Higher Education, influenced by the reforms undergone in this sector during the 1990s and 2000s (Law 2083/1992; Law 2188/1994; Law 3549/2007; Law 4009/2011). This official, legally bound regulation has offered a common, although general, description of the context, structures, basic principles and aims of all EDs in the country.

Flouris (Citation2010, 238) made a “critical periodisation” of developments in the relations of power and knowledge within the EDs from the 1980s to the present. This is a useful analysis for understanding the conditions “that influenced the formation of ‘discourse’ and ‘practices’ in the 25 years of their operation” as well as the current status of EDs. He identifies three periods of evolution. The first (1983–1989) is characterised as a period of “search and transition”, when the historical memory and the corporatist pressures exercised by the pre-existing institutional context of Pedagogic Academies were very strong. The second (1990–1995) is the period of “adaptation and stability”, when the departments were starting to find their pace and form their character as higher education institutions. The third period (1996–present) is referred to as a period of “modernisation and regulation”. According to his analysis, the departments are developing ‘new’ structural and technocratic features which, as we will discuss later in detail, start from, and are inextricably linked to, the implementation of OPEIVT I and II. The departments during this last period have been developing various educational and research activities (in-service teacher training programmes, Master's and doctoral studies etc.) (Flouris Citation2010).

In Greece today, teachers become qualified to teach by undertaking a four-year study at Departments of Pre-school Education (DPSE) and Departments of Primary Education (DPE), based in nine Greek universities.Footnote1 The majority of students enter the initial TE programmes at the age of 18 after taking the national higher education entrance exam. Master's and doctoral programmes are also offered by the EDs, aiming at the further specialisation of teachers and other professionals in various areas of educational research and practice.

Education Departments, like with the whole Greek university sector, enjoy autonomy in the design of their study programmes. These are developed by the departments’ academic staff, mainly according to their scientific and research profiles, but also according to special conditions related to differences in local and institutional contexts. Curricula are reviewed yearly by a committee of academic staff and proposed changes are approved by the General Assembly of the Departments and the Dean of the School (Law 4009/2011).

While sketching a picture of the current knowledge profiles of the Greek EDs, it is worth mentioning that they appear so immersed in their history that even now, 30 years after their upgrading into university departments, this history is reflected in related debates, especially with reference to discussions about ‘what and how’ should be taught in undergraduate courses for the education of future teachers. This conflict was acutely expressed at the beginning of the 1980s when the post-secondary teacher training colleges (pedagogic academies) started to be replaced by the new university departments. The literature paints a picture of this phase which reveals a deep division between the (new) teaching academic staff, formed around specialist subjects, and the (older) teaching staff formed on the basis of a generalist subject of ‘pedagogy’ (Stamelos Citation1999; Flouris Citation2010). The debate was about whether students should be taught specialised scientific knowledge or educated in how to discipline pupils and transmit knowledge in the classroom (Stamelos Citation1999). This conflict over the orientation and emphasis of the new curricula was apparent in the core questions on the purpose, content and relations that still accompany the development of the Teacher Education field (Biesta Citation2012).

This struggle, which has been interpreted as an expression of corporatist interests (Stamelos Citation1999; Flouris Citation2010), hindered the creation from the start of a clear framework and principles of subject integration in the curriculum. As Stamelos (Citation1999) states, these curricula exhibit a constant tendency to expand through the addition of new subjects. This character of the EDs’ curricula has been reflected in extreme shifts in the orientation of courses, initially towards the pole of ‘pedagogy’ (‘the how’) and later towards ‘subject specialisms’ (‘the what’). More recently, the conflict around curricula has been expressed as a ‘need’, posed gradually but insistently, for interdisciplinarity in the organisation of the curriculum. Still, the question remained as to why there were such a large number of subjects in the curriculum, especially as many of those subjects had little or no relation to the general aims of the curricula and the demands of school education (Stamelos Citation1999). In this respect, it is significant to note that in the evaluation of the Departments by invited peer-review committees of international experts in the period 2012–2014 conducted by the Hellenic Quality Assurance and Accreditation Agency for Higher Education (HQA), the large number of subjects studied within the curricula was pinpointed as a major weakness of most EDs (HQA 2014).

This old conflict among the academic staff due to their divergence in academic culture as well as corporatist interests, and the need of the new departments to acquire recognition and status within the university sector, have been among the most significant factors that have led to the co-existence in the study programmes of the two distinct traditions prevalent in Europe and worldwide: Education Sciences, as a broad knowledge and research area, and Teacher Education and Training (Hofstetter and Schneuwly Citation2002; CHEPS Citation2007; Tuning Project Citation2009). Hofstetter and Schneuwly (Citation2002) analysed and documented from the perspective of the History of Education the interrelations and overlaps between these two traditions. They discuss a striking difference among the two, namely that on one hand Education Sciences study programmes are recognised as educating experts and researchers in Education viewed as an academic discipline, while teacher education and training curricula are oriented to the preparation of future teachers and professionals for work in schools. It is interesting for the future development of the field that at the level of EU education policy the Tuning Project (Citation2003; Citation2009) preserved this distinction and implemented it in the description of subject-specific competencies for Education Sciences and Teacher Education, respectively.

In the Greek context, the co-existence of the two traditions in the EDs’ curricula and the possibility of a distinct identity of such institutions, comprising both a set of subjects that supposedly represent ‘the Sciences of Education’ and another one representing ‘Teacher Training’, perpetuates the old conflicts and rationales, reproducing ideologies and traditional divisions between theory and practice, knowledge and experience, knowing and doing etc. Moreover, the fact that the overwhelming majority of graduates of these departments inevitably seek jobs as teachers in pre-primary and primary schools, in the public and private sectors, largely defines the scientific and professional knowledge orientation of their curricula. This seems to agree with the idea that a ‘good teacher’ or ‘educational professional’, as an abstract and out-of-context aim of these departments, has no meaning at all, and that, in contrast, there is always the idea of a teacher who can respond competently to the purposes and objectives as defined by the particular needs of the state, society and socio-political and cultural contexts (Biesta Citation2012).

After numerous transformations appealing to national and social needs of Greek society, projected in the education and professional formation of teachers, what seems to be dominating the debates of expert groups and stakeholders, as well as the promoted education reforms, is the discourse articulated at the European level for a new generation of teachers. This portrays teachers in Europe as highly qualified professionals, able to work with new technologies, handle knowledge, and manage information effectively. Moreover, teachers should participate actively in society oriented to Lifelong Learning and be capable of contributing to social integration in local, national and global communities characterised by high diversity and mobility (European Commission Citation2005).

This complex ‘new mission’ seems to be one of the basic drivers of educational change in the Greek context of primary and secondary education in recent years. It is inscribed in both the rhetoric of contemporary political discourse on education, and the recently attempted reform initiatives of the “New School – Student First” (Ministry of Education Citation2009) and the “Social School” (Ministry of Education Citation2014), with the former introduced by a government of the socialist party, and the latter by a coalition government between the conservative and the socialist parties (2012–2014). Moreover, the legislation (Law 3848/2010) introduced by the former has been crucial in policy developments because it specified key competencies for teachers and leaders in education, and introduced evaluation and quality assurance for primary and secondary teachers and schools.

This brief account of the development of Teacher Education and training institutions, and the recent policy initiatives and legislation, suggest that these Departments are under the influences of diverse social and political forces. Therefore, any attempts to introduce reforms will be affected by the pressures and possibilities carried by the initiatives and practices of the EU and other supranational entities (UNESCO, the OECD's PISA, TALIS etc.) of global governance, initiatives which are spreading rapidly across national spaces (Seddon and Levin Citation2013). As we discuss subsequently, although we recognise that the historical, institutional and scientific dimensions discussed in this section are significant factors shaping the current profile of EDs and their curricula, the ‘opening’ of education systems towards ‘the supranational’ agendas about Education, and its contribution to the economy and society, is a crucial condition in order to understand current education developments in national settings (Zgaga Citation2013; Maguire, Citation2014).

European Education Policies and Changes in Greek Teacher Education Curricula

Education policy has been understood as the primary responsibility of European nation-states. However, national developments in higher education curricula of teacher education – the focus of the present paper – have been increasingly affected by global and European pressures to introduce changes and contribute to the realisation of the idea of Europe's ‘knowledge economy’ (Keeling Citation2006; Robertson Citation2009; Sarakinioti et al. Citation2011). In this line, Robertson (Citation2009, 65) shows how “Europe's approach to internationalising higher education is a multifaceted set of political strategies that, over time, has become more complex as an array of both national and European-level actors, and most importantly the European Commission, respond to pressures in the regional and global economies”.

In the decade of the 2000s, teacher education curricula reforms in Europe were induced by two significant kinds of political and policy influence. The first relates to the intergovernmental initiative of the Bologna Process for the development of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA). The other comprises the EU's actions for the ‘modernisation’ of higher education systems and their role in Europe (European Commission Citation2003). During that period, politics and action networks at the European level promoted a multitude of connections between the two policy agendas on higher education. In this respect, indications are, on one hand, the documents describing the contribution of the EU to the Bologna Process (European Commission Citation2009) and, on the other hand, the exploitation of EU-funded projects, such as ‘Tuning’ (Tuning Project Citation2003), by the Bologna Process in order to support research-based policymaking on implementation of the methodology of learning outcomes in higher education. The multidimensional and long-term political interrelation between the EU and the Bologna Process has led to the gradual development, support and stabilisation of a higher education policy framework in Europe, which has been expected to ensure more comparable, compatible, and coherent national systems, and to demonstrate high standards of institutional autonomy, curricula based on students’ learning outcomes, a close relationship between teaching and research, the employability of graduates, and the attractiveness of European higher education systems (ENQA Citation2009).

Within the framework of the establishment and operation of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA), what has systematically been promoted is a shift away from study programmes organised on the basis of subject disciplines to programmes organised around courses, developed on the basis of expected learning outcomes (London Communiqué Citation2007). Learning outcomes refer to descriptions of specific knowledge, skills and abilities that learners are able to demonstrate at the end of any educational process, long- or short-term, in which they participate (Tuning Project Citation2003). This kind of methodology for curriculum development moves the focus of the entire educational process from the “content” and “purposes” to the “processes” of learning and assessment, a shift which, as we will discuss later, leads to what Biesta (Citation2012, 10) describes as the “learnification” of education.

In the spaces created by the policies of lifelong learning and Europeanisation, the shift to learning outcomes operates in ways which impel education and training institutions to “modernise” (Cedefop Citation2009, 14), as outcomes have been inextricably linked to the objectives of Quality Assurance and Accreditation of higher education institutions (ENQA Citation2010) and the development of the European Qualification Framework (European Union Citation2011). More specifically, implementation of policies and practices across Europe related to learning outcomes aims to contribute to the opening up of access to learning for all, the recognition and validation of learning in non-formal and informal environments, and the facilitation of mobility in and across education and the labour market for individuals at national and international levels (Cedefop Citation2009).

On the other hand, the European Union has for many years been making serious efforts regarding the identification and description of certain principles and competencies for teachers recruited by the European national education systems (European Commission Citation2005; Citation2007). In the strategic programme “Education and Training 2010”, teachers’ education and training emerged as a significant action line for promoting the objectives of the Lisbon Strategy. The EU has ‘intervened’ in what has traditionally been a nationally oriented field of policy and practice by identifying and disseminating best practices for teacher education, in-service training and professional development. The European Commission's (Citation2005) “Common European Principles for Teacher Competences and Qualifications” is a foundational document in its attempts to provide a specific orientation to the reform of teacher education and profession in EU member states. Although short, this document describes in detail the competencies and skills teachers must demonstrate in order to be successful in achieving the contemporary objectives of school education during their everyday professional practice.

According to this document, the common principles to guide the development of policies, aiming to ensure the quality and efficiency of education systems, are the following: a high percentage of teachers with higher education qualifications; a profession perfectly integrated in the lifelong learning context, a condition which ensures continuity between the initial, induction and continuous education; and a profession demonstrating mobility based on partnerships with other stakeholders. Regarding lifelong learning, the document recommends that national and regional policymakers develop permanent and adequate funding strategies for formal and non-formal activities of teachers’ continuous professional development. Teachers’ courses should include training in specialised subject disciplines and pedagogy, and these should be offered throughout the duration of a teacher's career. Further, regarding the content of curricula for the initial and professional development of teachers, the document outlines the importance of interdisciplinary and collaborative approaches to learning.

Most importantly, this European Commission document describes three key competencies for school teachers. First, they should be able “to work with others”, supporting the independent development of each learner in ways that enhance their collective accomplishments. While demonstrating self-confidence, they should become involved in teamwork with their colleagues in order to enrich teaching and learning processes. Second, teachers need “to work with knowledge, technology and information”. More specifically, they have to work with diverse forms of knowledge and reflect on it in ways that allow them to build and manage open learning environments. Further, teachers should feel confident to make effective use of ICT and integrate technological means into teaching and learning processes, whenever appropriate. Third, teachers must be able to manage information effectively and to direct learners to the networks where they can find and use information. Moreover, teachers in their everyday practice need to bring together a good understanding of theoretical knowledge, insights from their participation in lifelong learning processes and experiences from their professional work so as to develop a range of teaching and learning strategies compatible with their students’ needs.

Finally, teachers should be able “to work with and in society”. Society here carries the complex meaning of a global community where citizenship, multiculturalism, mobility, cultural diversity of students and the recognition of common values are in line with the demand that teachers should make a positive contribution to quality assurance systems. In contemporary societies, teachers are required to encourage learners to act as globally oriented EU citizens who show respect for common social values. All these require teachers to be able to cooperate effectively with the local community, with partners and with stakeholders in the education sector, e.g. parents, teacher education institutions and other representative groups.

In Greece, curricular knowledge, educational qualifications and skills were not central issues in the public debate on the university in the decade of the 2000s. The issues of learning outcomes and competencies have begun to appear on the official political agenda very recently due to EU pressure to develop a National Qualifications Framework (NQF). The changes promoted to the university study programmes in the 2000s were mainly linked to the implementation of the Operational Programme for Education and Initial Vocational Training II (OPEIVT II), co-financed by the European Social Fund (ESF) and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), together with national resources (Gouvias Citation2011; Sarakinioti Citation2012).

This funding programme was developed around five priority action lines specialised in specific measures and sub-actions of intervention. Here, we focus on the second priority action line, referring to the promotion and enhancement of education and vocational training within the framework of an integrated system of lifelong learning. The objectives of Measure 2.2 on “Reforming of Study Programmes – Expansion of Higher Education” have on one hand been the modernisation of curricula at all levels of education, aiming at the better preparation of young people to enter the labour market and, on the other hand, the expansion of undergraduate and graduate curricula with subjects adapted to new labour market needs (Ministry of Education Citation2006). Measure 2.2 has been further specified into three sub-actions of intervention. The modernisation of undergraduate higher education study programmes is a category within Action 2.2.2. (Ministry of Education Citation2006). More specifically, for expanding and upgrading higher education curricula OPEIVT II provided funding to support changes of the following kinds: The fast adoption of new technologies in teaching practices and evaluation, together with the use of multiple information and literature resources in the learning process; the development and adjustment of printed and electronic educational materials; the supervised self-teaching or teaching in small groups as an additional option; the distributed learning environments and the development of virtual laboratories and specialised portals (Ministry of Education Citation2007).

In the same line, the document repeatedly stresses the need to develop “methods and practices for every specialisation, in order to make bridges between the institutions of higher education and the labor market” (Ministry of Education Citation2007, 102). Regarding the organisational and knowledge core of the studies, the main changes promoted by the Operational Programme are: The introduction and implementation of new, improving activities such as the organisation of studies in modules; the institutionalisation of processes for continuous self-improvement for the teaching staff; the gradual implementation of interim assessment processes for the students in most courses; individualised counselling to reduce stagnant attendance; development of generic skills; promotion of self-motivation, freedom of thought, creativity and capacity for self-learning; the development of flexibility in the study programmes; the identification of emerging interdisciplinary areas at the intersection of [university] department[s]; and the initiation into research practices (Ministry of Education Citation2007).

Since the early 2000s, the EDs have displayed a strong orientation to the European and international contexts of policy and practice. This tendency can be traced in the increase of courses in the curricula with an orientation to education policy and internationalisation issues, as well as courses promoting the so-called European Dimension in education. What is of most significance, in their response to the demand to modernise their curricula, is that a large majority of them (14 of the existing 18 Education Departments), in the period 2000–2006 chose to introduce changes and reform their undergraduate study programmes, exploiting the EU funding opportunities of the OPEIVT II. Crucial to the influence these reforms have exerted on the formation of the modern profile of Greek EDs are the kind of choices the latter have made and the changes they have promoted in order to improve their curricula. Such changes include the introduction of new courses on gender and environmental issues, the enhancement of the practicum programme, technological advancements, improvement of the departments’ premises and equipment, and the development of repositories documenting good teaching practices.

To sum up, in this section we provided an account of current developments in Greek TE resulting from history, present circumstances at the national and local level, and the objectives of global and European policies on education as a complex and dynamic field.

‘Modernising’ Teacher Education

The changes in the forms of knowledge and types of practice in the curricular organisation of EDs in the course of their development have to be contextualised and interpreted as aspects of the broader “modernisation project” aimed at education, teachers’ training and the teaching profession (Beck Citation2008, 122). Modernising projects and processes refer to the political programmes developed by governments in nation-states, in the conditions of globalisation and post-welfare regimes (Seddon and Levin Citation2013; Sifakakis et al. Citation2015). The usefulness of the term is that it stands as a reminder that national policies today are more and more national manifestations of globalised education policy discourses and practices.

Following Beck's analysis, we can describe two moves towards ‘modernisation’ in the Greek education system which have directly or indirectly affected the teaching profession, teachers’ lives and identities. The first occurred under the operational frameworks of European funding at the national level as they were implemented in a series of four programme periods, starting in 1994 and looking ahead to 2020. As already alluded to, teacher education curricula reforms have taken specific directions under the influence of OPEIVT I (1994–1999) and OPEIVT II (2000–2006) objectives. The subsequent National Strategic Reference Framework (NSRF) 2007–2013 and 2014–2020 supports major policy reforms in school education – e.g. “New School – Student First” (Ministry of Education Citation2009) and “Social School” (Ministry of Education Citation2014) – aiming at an open, more inclusive, innovative and efficient school, as well as exerting pressures to make teachers more competent, productive and effective.

The second move relates to the multiple and intensive pressures for policies and practices of quality assurance and evaluation across the public sector, and in education in particular. The development of systems for quality assurance at all levels of education has been at the forefront of the successive governments’ policy agendas from 2009 onwards. The objective of “being accountable to others” (Beck Citation2008, 123), e.g. central government, creditors, society, parents etc., has been spreading as a dominant element in the reformative discourses about both TE institutions and teacher schoolwork. It is important to recall that the EDs were recently subjected to an internal and external evaluation conducted by the HQA. The external evaluation reports depict and transfer the international experiences and good practices of the participating experts, contributing to the national debate about the purposes of teacher education, how such purposes relate to the content of the curricula, as well as the pedagogy and the methods for evaluating students. Such policies and practices of accountability were deemed to be an imposition of ‘external’ criteria of evaluation on the pedagogical field of Greek higher education institutions, attempting to regulate the pedagogical context of knowledge organisation (Sarakinioti Citation2014). Therefore, in 2013 (Law 4142/2013) teachers found themselves at a crossroads of deep reforms regarding the assessment of their qualifications and competencies, as well as their effectiveness and adequacy to respond successfully to the modern demands and new standards of education quality.

During the last five years, controversies and resistance have evolved, emanating from within the academic community and various social, political and professional groups, arguing for the deceleration of the aforementioned reforms, which have been perceived as being permeated by neo-liberal values and orientations. So, presently, one of the first measures that the left-wing government elected in January 2015 has announced is the abolition of Law 4142/2013 on teachers’ assessment. Thus, at this moment, teacher education curricula operate in conditions of increased uncertainty caused by the absence of both a governmental framework for teachers’ education and training and clear directions for schools. These conditions may have effects on what is perceived to be legitimate principles of education knowledge and legitimate or acceptable kinds of teacher professional conduct and forms of identity.

Teacher Education in global societies: Foregrounding knowledge and identities

The literature on TE is extensive and comes from different theoretical and research traditions of the education sciences and pedagogy (‘didactics’ of different subject areas, educational psychology, sociology and history of education, education policy and administration etc.) (Townsend and Bates Citation2007; Cochran-Smith and Zeichner Citation2010; Menter et al. Citation2010b). A systematic review of teacher education research in the UK from 2000 to 2008 identifies eight popular topics of inquiry (Menter et al. Citation2010a). On the basis of 446 relevant articles that were reviewed, the authors conclude that “professional learning is most frequently used in relation to school teachers-beginning teachers (pre-service, induction or early career teachers) or mentors/supporters in school settings (experienced/veteran teachers supporting novice teachers in the practicum/field experience). 256 papers focus on the regulatory frameworks and policies that govern teacher education in the UK … 148 (33.2% of the total) focus on curriculum and assessment, and 110 (24.7% of the total) focus on partnership relations between schools and providers of teacher education” (Menter et al. Citation2010a, 133). On the other hand, issues of “equity”, “ethics” and “teacher educators’ professional development” appear to be at the periphery of research interests (ibid., 133).

Another important review of relevant literature referring to 15 different national systems, based on Europe, Australia, Asia and America, shows that in the history of teacher education the field “has consistently been a significant site of social and political debate in many countries” (Menter et al. Citation2010b, 17). Among the inter-related themes of this contestation are the “struggles for ‘positioning’ and ‘ownership’ of teacher education”; the “attempts to define teaching as a profession – and to establish whether teaching has a distinctive intellectual knowledge base”; the “debate over teachers’ terms and conditions, as well as pay, and the role of teachers’ unions”; “the emergence of professional bodies to uphold professional standards and to control entry into the profession”; and “the economics of teacher supply and demand” (Menter et al. Citation2010b, 17). The review discusses in detail the close and multi-dimensional relations between teacher education and professionalism, revealing that the processes through which teacher education has been formulated, developed and operated as a specialised field of knowledge, practice and research worldwide are in many respects inseparable from the “differing conceptions of teachers’ professionalism, underlying policy and research literature” (Menter et al. Citation2010b, 21).

Four types of teacher professionalism are identified by the relevant literature as influential for teachers’ training and identities (ibid.; Menter Citation2010; cf., Cunningham Citation2008). The first one describes the “effective teacher” of high standards and competencies, who manages to respond to the needs of measurement, accountability and performativity. The second model, having its roots in Dewey's and Schön's works, describes the “reflective teacher” (Menter et al. Citation2010b, 22). In this case, professionals approach teaching and learning in classrooms as processes of active decision-making. The third type refers to the “enquiring teacher”, who systematically undertakes research in his/her everyday work (Menter et al. Citation2010b, 23). Finally, the literature describes the “transformative teacher” who incorporates elements and practices of reflection and research and mainly acts as an activist (Menter et al. Citation2010b, 24). Teachers of this kind exercise teaching practices that aim to prepare pupils in ways which can contribute to societal transformation.

These types of teacher professionalism, which reflect political and educational ideologies, are important resources for understanding and interpreting teacher education in contemporary societies, as “[e]ach of these leads to different emphases within teacher education across the full continuum” (Menter et al. Citation2010b, 21; Menter, Citation2010). Relevant research production largely concerns school-based studies, or studies focusing on the exploration of school- teacher education partnerships, teachers’ induction into the profession, issues of mentoring, and the analysis of the relationship between teacher training and the reforms in the content of school curricula (Menter et al. Citation2010b). Another important body of literature poses critical questions on policy, politics, the governance of teachers’ work and their relations to the state (Menter Citation2010). This literature articulates a critical approach to the impact of the globally spread technologies of performativity and new managerialism (Ball Citation2003), as well as the policy processes for data gathering, inspection and self-evaluation, which acquire a new regulative role over teachers’ work and identity in the new governmental space of Europeanisation (Ozga Citation2009; Citation2012).

Within this perspective, Robertson's critical analysis of teachers’ work in contemporary times raises the issue of the “denationalisation” (Robertson Citation2013, 77) of their teaching and learning practices and the transformations of their roles as agents in the field which Bernstein (Citation1990; Citation2001b) has called the field of “symbolic control”. In her article entitled “Placing teachers in global governance agendas”, Robertson (Citation2012) explores the ways in which the OECD and the World Bank have intervened through policy initiatives such as the TALIS survey and the “Teachers Matter” report in “promoting a reframing of teacher policy and practice inside national territorial borders” (ibid., 85). Utilising Bernstein's theoretical concepts of classification and framing, Robertson describes the refashioning of “what was meant by ‘the good teacher’ – to be a competent teacher” (ibid.). Her main contribution relates to the linking of the reordering of the field of symbolic control to the imposition of new apparatuses of certification and regulation of teachers in global governance spaces. As she amply illustrates, what is important for understanding the globally based processes of the denationalisation of teachers’ work is the analysis of “the way ‘the good teacher’ is reclassified (as the competent teacher) and strongly framed (that is, that the elements that make up the competent teacher are highly specified) by the OECD” (Robertson Citation2012, 85).

Issues of the regulation of nationally based teachers’ work and identities in the context of globalisation and the knowledge economy were also raised by Bonal and Rambla (Citation2003) in their paper entitled “Captured by the Totally Pedagogised Society [(TPS)]: Teachers and teaching in the knowledge economy”. Referring to Bernstein's concept of TPS – developed in his late work (Bernstein Citation2001a) – and its basic premise that “[t]he weak state of the global economy requires a strong state in the pedagogic field” (Bonal and Rambla Citation2003, 175–176), they described systematically and interpreted the changes that occurred in the Spanish educational context. More specifically, they analysed the Spanish state practices of designing, planning and implementing curriculum reform in the early 1990s, discussing the consequences these changes had on teachers’ work and their professional identities. Bonal and Rambla showed how the weakening of the classification between forms of knowledge and fields of practice – Official Recontextualising Field (ORF) and Pedagogic Recontexualising Field (PRF) – combined with the spread of “a performance-oriented mode of pedagogy … by the official pedagogic discourse”, in the late 1990s, entailed changes in the conditions of state regulation over teachers and the status of their autonomy (Bonal and Rambla Citation2003, 178). As the authors note, the particular demands for modernised and quality assured national education systems make teachers key actors in the reform processes, assigning them the responsibility and the duty “to prepare students for the new requirements of work and life in the global economy” (ibid., 179). As they put it, teachers

are called to rapidly update their specialised forms of knowledge and have to be capable of teaching them, even before other agencies of recontextualisation produce and distribute new pedagogic discourses. This locates teachers in an uncertain position between knowledge and pedagogy. There are knowledge objectives to be achieved, but it is a matter of teacher responsibility to innovate teaching methods, to maximise knowledge acquisition. Pedagogic autonomy is the vehicle for educational quality and efficiency in a performance-based model. Self-responsibility and flexibility are the means for a very specific end: to ensure that the knowledge taught at the school is worthwhile and has economic value. Here we have another paradox: teachers are expected to be pedagogically autonomous, but this pedagogic autonomy does not have value in itself. It is a type of pedagogic autonomy that has to be knowledge oriented under the official scrutiny, since its validity eventually depends on its alleged utility for developing the necessary knowledge required by the market. Thus, it is an autonomy that nobody wants (Bonal and Rambla Citation2003, 180).

The performative models of pedagogised knowledge, as described by Bonal and Rambla (Citation2003, 169, 180), are inscribed in processes of “endless learning” and “conceptualised as a means for achieving the goal of learning to learn” for both teachers and students. In this regard, it is of particular interest that Biesta (Citation2012) focuses on learning and develops his ideas on the “learnification” of education in a paper about the future of teacher education. His arguments about the meaning of the shift from teaching to learning in the education field are based on his review of a central EU policy text on teachers, which refers to key competencies (European Commission Citation2005). In Biesta's critical analysis (2012, 12), “[t]he problem with the rise of the language of learning in education is … three fold: it is a language that makes it more difficult to ask questions about content; it is a language that makes it more difficult to ask questions of purpose; and it is a language that makes it more difficult to ask questions about the specific role and responsibility of the teacher in the educational relationship”. He argues that restricting the meaning of education to a general, open and flexible approach to learning, which de-contextualises it – e.g., not learning of something for particular purposes or learning from someone – makes educational processes individualistic, instrumental and functional, preventing teachers from being able to make judgments about what is educationally desirable. Using Bernstein's (Citation2000) terms, as utilised for instance by Bonal and Rambla (Citation2003) above, we can argue that the current developments and shifts within the education field restrict the power of teachers to exert control over the knowledge resources, the recontextualisation processes, and the processes of teaching, learning and practices of evaluation.

Literature produced in the tradition of critical realism, utilising Bernstein's theory, elaborates arguments concerning changes in power and control relations. Beck and Young (Citation2005; also see Beck Citation2008; Citation2009) explore changes in teacher professionalism, analysing the processes of restructuring of their knowledge base and their identities in England. Their work contributes greatly to the development of a critical way to think about the teaching profession with reference to their position as agents in the PRF and as subjects in modern state governing (Bernstein Citation2001a; Beck Citation2008). Young and Beck (Citation2005) applied the theoretical framework of Bernstein (Citation2000, 52) to “singulars”, “regions” and “generic” forms of curricula to describe the changes occurring in professional knowledge, and to explain the “assault” of the professions by state impositions. According to their analysis, in the case of teachers and medical professionals, pressures come from ever greater state regulation, while in other cases, such as law, from the encroachment of the market.

In this approach, legitimate knowledge and identities are constructed through three main transformations in power and control relations. First, through the weakening of boundaries between (classification) previously strongly insulated disciplinary subjects (singulars); second, through transformations in the mode of control shaping pedagogical relations and communication (framing); and, third, through transformations in the meaning orientation of the expected identities, from dedication to values and practices of the academic field, as crucial agents in the PRF (introjection), to values projected from agents of the ORF or the market towards practical fields of application (projection). Changes at these three levels are associated with shifts in the knowledge base of the professions, from singulars (physics, chemistry, economics, psychology etc.) to recontextualisions of singulars into larger units of knowledge – regions (engineering, cognitive sciences, management etc.) and, further, to the development of generic and subject-specific skills (generics) (Bernstein Citation2000).

In a similar way, our approach to research on TE combines Bernstein's concepts of classification (strong/weak), framing (strong/weak), and meaning orientation (introjection/projection) to develop a theory-informed model for the analysis of the principles of pedagogical discourse in higher education study programmes. Our model operates as an analytical tool to describe shifts between eight basic types of curricular knowledge, four of which were identified in our data as dominant. These are: Singular academic, New professional-Generic, Old professional, and Interdisciplinary academic (Sarakinioti et al. Citation2011; Sarakinioti Citation2012). Briefly, the main shifts that these types describe are a move from strongly insulated forms of knowledge, with an inward looking orientation (Singular Academic), to those projected outwards to various professional fields (Old Professional), or to forms with an exchange value in the market (New Professional-Generic). The latter focuses “upon the exploration of vocational applications rather than upon exploration of knowledge” (Bernstein Citation2000, 69). The model also describes a type characterised by “an integrated modality of knowing and a participating, co-operative modality of social relation” (ibid., 68) (Interdisciplinary). The key distinction between Interdisciplinary and New Professional-Generic knowledge construction is whether content selection is driven by criteria that emerge from disciplinary knowledge bases or those determined by job market demands. These theory-informed analytical tools allow us to explore, on one hand, study programmes that set out to be the basis for ‘specialised identities’ for teachers and other educational professionals and, on the other hand, those that aim at ‘flexible identities’. The former enables students to project themselves meaningfully and to recover a coherent past, while the latter enables students to respond to “flexible performances” and to “intermittent pedagogics”, adjusting themselves to external contingencies (Bernstein Citation2000, 55, 59). Moreover, each of these types of study programme has consequences for the legitimation of certain disciplines and forms of knowledge and research.

Methodology

Our methodological approach is a genre of discourse analysis utilising the theoretical model described in the preceding section, and asking questions about changes in the strength of boundaries (classification and framing relations), and shifts in meaning orientations (introjection/projection). The aim was to rigorously describe and explain TE curricular changes over time, concentrating on two periods, the middle of the 1990s and the late 2000s. At the empirical level, the object of our analysis was the core official documents relevant to the programmes of study of the 18 EDs operating in Greece. Crucial among such documents are the students’ handbooks, which constitute a temporal and integral dimension of the institutional and educational order of the departments, functioning as public displays of valid study programmes. More specifically, two characteristics make them reliable data sources on the topic. First, they are official documents, which are generated through collective processes, embodying the “collective memory” of work/knowledge organisation and change within each of the institutions (Silverman Citation2004, 57). Second, they are texts “produced for external users, or even for public, consumption” (ibid., 57). They are “among the techniques and resources that are employed to create versions of reality and self-presentations” (ibid., 57). In addition, these texts are updated annually. We can thus reasonably assume that they would depict changes introduced to study programmes. Indeed, handbooks, displayed at the time of the research in 14 out of the 18 departments participating in the OPEIVT II programme had incorporated the changes made to their study programmes. In fact, this was one of the deliverables of the EU project (Sarakinioti, Citation2012).

In the course of this research, the documents selected were students’ handbooks, corresponding to the study programmes of the 2008–2009 academic year and the early 1990s – 36 handbooks in total. What was subjected to analysis, through the core concepts of classification, framing and meaning orientation, and their combinations in our analytical model, was the message system of content, pedagogy and evaluation in each study programme, the latter being the unit of our analysis. The various data sets produced correspond to the main pedagogical activities described in each programme of study, namely the courses, the practicum and the writing of dissertations. The principles of knowledge selection, and practices of teaching, learning and evaluation were operationalised in ways that allowed the identification of criteria concerning the level of specialisation of knowledge resources, the forms of pedagogical communication, and the orientation to the meaning of knowledge organisation. These criteria were applied to all pedagogical activities and to the programme as a whole.

Several data sets were produced through the reading and re-reading of the information contained in the handbooks. These kinds of analysis allowed us to reveal the complexities and contradictory messages of the curricula and, at the same time, to capture the dominant messages, especially through characterisation of the courses studied, vis-à-vis the eight types of the model. It is important to say that, although the approach was basically qualitative, at an advanced level of analysis certain quantifications were produced in order to construct economical representations of curricular changes. In the section that follows, we make use of these qualities of our analysis.

Dominant knowledge and forms of practice in Teacher Education

A brief description of the university study programmes

The analysis of the students’ handbooks for the periods studied shows that the need invoked for changes was the key driving force for developing the current undergraduate curricula of teacher education, aiming at their upgrading and modernisation. The discourses legitimising the promoted changes were mainly articulated with reference to the labour market problems of teachers, especially pre-school teachers whose unemployment rate for many years has been much higher than for school teachers of primary education (Sianou-Kirgiou Citation2010).

It is important to note that during the last five years EDs have faced new challenges and serious constraints in the course of reforming their curricula. Teachers’ unemployment rates have increased dramatically since 2008, the year when new permanent teaching staff were last recruited to cover the needs of public schools. This means that teachers as a professional group in Greece are ageing while, on the other hand, the knowledge and competencies of new graduates are being wasted. In addition, the decrease in academic and administrative staff numbers at the level of university departments is hampering their efforts to fulfil their current mission and plan for sustainability.

Data show that the 18 EDs share some important common features but also differ in various respects in the ways they manage power relations in their effort to select and organise the core learning activities of their undergraduate study programmes (Sarakinioti Citation2012). In general, they are structured in terms of courses recontextualising knowledge resources from various educational disciplines and research areas. Among the most widely offered subject courses are ‘didactics’ of various subject areas, pedagogy, children's literature, history of education, sociology of education, psychology, education policy, arts education, ICT in education etc. The programmes of study offered include compulsory, compulsory specialised courses and free electives. Another common element of Greek EDs’ curricula is the ‘practicum’, whereby students, as trainees, are required to spend several weeks in teaching practice in pre-primary and primary public schools. Finally, writing a research dissertation is the third common axis of curriculum development. Students of EDs should successfully attend an average of 45 courses and gain a maximum of 240 ECTS credits to obtain their degree.

The sections that follow present a synthesis of the qualitative data produced in the context of analysing the knowledge status, direction of changes and crystallisations in Greek TE (Sarakinioti Citation2012). Data illustrate the dominant pedagogical principles of classification, framing and meaning orientations, which regulate course, practicum and research dissertation practices (Bernstein Citation2000).

The articulation of courses

Starting from the analysis of the structural arrangements for the courses offered in the 18 study programmes, data show that they are organised according to three models. In five of them, the courses are grouped in subject areas/divisions, in nine cases they are organised in modules or units and in four cases both subject areas and modules/units are used. During the period of analysis, significant changes occurred in 11 out of the 18 curricula. The direction of these changes in 8 of the 11 curricula – 6 of them from pre-school EDs– was towards strengthening modularisation in knowledge organisation. Data show that the organisation of courses in modules or units has been a traditional characteristic of curricula in Greek EDs, a tendency which has been strengthened by the framework and objectives of implementing OPEIVT II for the expansion and modernisation of HE. By definition, such kinds of knowledge organisation are regulated by weak classifications. However, the analysis showed that in most of these, the cases referred to as modules/units are nothing more than strongly classified sets of courses which under general descriptive titles represent schemes of “pluridisciplinarity” rather than forms of knowledge “regionalisation” (Stavrou Citation2011, 144; Bernstein Citation2000, 53).

Regarding the analysis of the courses per se, the data indicate that, in the period of study, there was an expansion of the knowledge base of the curricula. More specifically, 14 departments increased the number of courses offered while the rest of them (N=4) reduced them. presents the number of courses offered and analysed in total in the programmes of the late 2000s, as well as the change in each department from the early 1990s.

Table 1. Illustration of basic figures regarding the analysed courses in Greek Departments of Education and Training

Qualitative data on the pedagogical practice dominating the TE field show that in both periods of study the majority of courses offered are concentrated in four categories of our analytical model, namely, singular academic, old professional, interdisciplinary academic, and new professional-generic. In the curricula of the 1990s, the study reveals greater diversity in the distribution of courses in these four categories; while in the current study programmes the strongest category of knowledge organisation – in almost all of the EDs is the new professional-generic form. presents, indicatively, the distribution of the 18 curricula into the four knowledge categories of the analytical model, according to the dominant pedagogical ‘voice’ they articulate.

Table 2. Illustration of the distribution of curricula in the analytical model

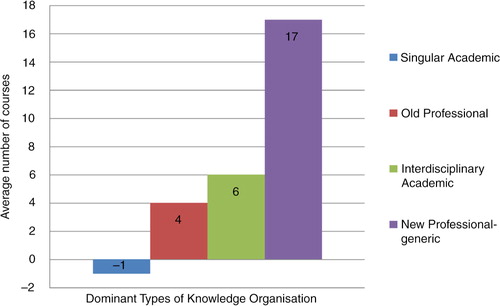

The recorded changes in the forms of knowledge towards recontextualisation principles of weak classification, strong framing and projected meaning orientation, that is, the shift to the new professional-generic form of pedagogical practice, is one of the most important findings of the study. In 15 of the 18 curricula of the late 2000s, the new professional-generic type is the dominant form of knowledge organisation compared to any other knowledge organisation type in our model. Examples of titles of courses identified in our analysis as ‘new professional-generic’ forms of curricular knowledge are: Management of the school classroom, A cross curricular approach to values, Parent counselling, School libraries, Organising visits to museums of technology and science etc. below presents a snapshot of the average number of course changes per type of knowledge organisation in ED curricula.

Data produced from the analysis of the courses provide strong evidence of the emergence and wide diffusion in the field of TE of knowledge modalities and forms of practice that are based on weak insulation between the various fields and contents of knowledge (Beck and Young Citation2005). What legitimises the selection and recontextualisation of knowledge resources in this case is their functional meanings related to local and concrete environments of application and use. These kinds of content respond to current and often ephemeral needs and problems of school education or even other providers of broadly educational services (e.g. museums, hospitals, play centres etc.), equipping future teachers with practical tools to handle professional reality, which by the time they have joined the profession will probably have changed. Theoretical assumptions are kept implicit and invisible from students. In terms of pedagogical communication, academics retain the control (strong framing) over the selection of knowledge resources and the pedagogical methods used. In seminars, they guide students to actively engage in planned learning activities such as projects, workshops, writing short essays or making presentations. What is marginalised in such contexts, and to a large extent replaced by the instrumentality of the new professional models, is “the forms of knowledge that permit alternative possibilities to be thought – thereby reproducing imaginary concepts of work and life that abstract real experiences from the power relations of their lived conditions and negate the possibilities of understanding and criticism” (Beck and Young Citation2005, 193; Bernstein Citation2000).

The status of the Practicum

The practicum has been a pivotal axis of ED curricula in all periods of their development, aiming at the induction and practical training of student teachers in school education. It is a compulsory activity for students in all TE departments. The way the practicum programme is placed and executed in the curricula differs in terms of time, duration, the prerequisites for course attendance, and the credit units offered. However, the general framework for realisation of the practicum has some common characteristics that are important for understanding how EDs handle the crucial issue of their partnership with schools and teachers’ professional practice (Menter et al. Citation2010b). In general, practicum activities take place on both the premises of the collaborative schools and in the departments through teaching simulations, especially in subject specialists’ courses. In most curricula, the practicum lasts several weeks, scheduled throughout the last two years of study. Under the guidance of class teachers, and with the support of teachers seconded to the departments, students gradually get involved with systematic classroom observation activities, first as assistants and later independently.

Data show that no radical changes occurred in the organisational framework and knowledge relations regulating the practicum programmes in the two periods of study. Their pedagogical context aims to introduce professionally oriented practices, processes, values and elements of identity into the undergraduate curricula of TE. The knowledge and pedagogical processes – selection, pacing, sequencing, and evaluative criteria (Bernstein Citation1977) – of students’ presence in the schools and their apprenticeship are regulated to a great extent by the departments. The systematic analysis of the practicum programmes – as depicted in students’ handbooks – in terms of classification and framing shows that almost all departments have enhanced their control over the framework of their practicum, mainly by enriching their content with specialised knowledge resources in pedagogy, ‘didactics’ and their teaching applications, as well as by describing more systematically the conditions of their students’ presence in schools. This is a strong indication that the departments, in their partnership with the schools, maintain strong boundaries and keep control over the whole process. The dominant principles of practicum programmes represent in the curricula a constant component of what our analytical model describes as old professionalism.

The compulsory character of the practicum programmes is an indication that school-based training for future teachers is valued as an important element of undergraduate curricula of teacher education and therefore might exert a great influence on how student teachers construct their professional identities.

The status of writing a research dissertation

The research dissertation is the third core component of ED curricula in the two periods studied, aiming at knowledge development in research and academic writing. It is an optional activity in 15 of the 18 curricula and is offered to students in the last two or three semesters of their studies. The pedagogical context for producing a research dissertation recontexualises academically oriented practices, processes, values and identities. Dissertation writing has different weight in the various curricula, although on average it corresponds to the successful completion of three subject courses and gives 12 ECTS credits. In the course of writing a research dissertation, under the supervision of academic staff students are asked to conduct small-scale research, undertake a literature review, use theoretical resources, and analyse and present data. It can be described as an individualised pedagogical process based on the choice and active engagement of the students and their close collaboration with their tutors who act as mentors to initiate them into research processes and practices.

The optional character of writing a dissertation is an indication that practising educational research holds a secondary position in initial teacher education and therefore might not exert a strong influence on teachers’ identities. However, the fact that various other research-oriented activities – some of them compulsory – are included in the study programmes (e.g. research and methodology seminars, research-based activities in the course of the practicum, essays as a means of assessment in various courses etc.) challenges this first impression about the role of research in the training of Greek teachers. It appears that departments in the last terms of a curriculum programme are obliged to balance between their interest in research, displayed in an increase in their research activities (e.g. master's and doctoral programmes, research projects, publications etc.), and the challenges posed to the institutions and academics by the massification of higher education, especially at the undergraduate level of studies. Therefore, keeping the research dissertation optional appears to be mostly a curricular choice which is forced by a shortage of the staff needed to support the heavy workload of mentoring, rather than negatively assessing the importance of research in teacher education and their professional practice.

From our theoretical perspective, the way the research dissertation appears in the majority of teacher education curricula represents a form of invisible pedagogy (Bernstein Citation1977). The optional character of the particular educational activity in the curricula – that is, the weak framing controlling the participation of students – makes it ultimately an ambiguous activity, regarding the messages transmitted to students on its importance and contribution to their cognitive formation as specialised professionals. Research is a marginalised ‘voice’ in the curricula compared to the content of the courses and the practicum, so students’ choice to participate in the pedagogical processes of completing a research dissertation turns out to be a determining factor for the impact that research can have on students and their pedagogical and professional identities.

In Bernstein's (Citation1990, 129) terms, this is connected with the “recognition” and “realisation” rules students possess for decoding the pedagogical messages of various forms of knowledge and understanding the consequences they can have for their future professional development. These issues are related to their criteria on what is a successful learning trajectory in the course of their undergraduate studies, e.g. to graduate on time and get a job, to acquire new learning experiences, to prepare themselves for advanced studies and research etc. Cultural and social capital, their family background, the already consolidated pedagogical identities and the ways they relate to various forms of knowledge, as well as their plans for their future professional and academic careers are crucial factors in students’ choices and trajectories, exerting influences on their agency and their “ability to imagine a future possible self” (Clegg Citation2011, 96). This allows us to argue that the curricula studied, which tend to attract students from less privileged socio-economic backgrounds (Sianou-Kyrgiou and Tsiplakides Citation2010), by presenting the dissertation as an optional pedagogical activity, maintain the conditions for the reproduction of established assumptions and practices concerning research and who can legitimately do it. This is not in favour of those students who do not have the resources during their studies to recognise the importance of research for their knowledge formation and professional development. Therefore, they might inadvertently exclude themselves from future possibilities by the very act of not choosing the research dissertation as part of their individual learning programme. This is an issue worthy of further investigation.

Conclusions: Knowledge and identities in Teacher Education

The starting point of this paper was that TE is a privileged point of entry into the question of how European and global policies on HE influence the governance models, the redistribution of pedagogical means and the forms of educational knowledge offered by the institutions of the various national HE systems. Our theoretical argument is that the new conditions of global governance make TE more open to change and transformation, increasing the demand for research on how global policies on HE programmes of study travel and are enacted in various national settings of policy production, and through education practices of selection, organisation, pedagogical communication and evaluation of academic knowledge (Sarakinioti Citation2012; Sarakinioti et al. Citation2011). Our approach to research utilises a theoretical model based on concepts drawn from Bernstein's theory (Citation1990; Citation2000). This model helps to direct teacher education research in describing, analysing and explaining educational knowledge change, and to assess its consequences for both the departments’ profiles and prospective teachers’ and indeed academics’ identities.

The European educational policy initiatives played an important role in the process of Greek teacher education curricula reforms and their implementation in the 2000s. Our research revealed a number of incremental changes that occurred in the course of time, which seem to reproduce the diversity in the organisational principles and the subject content that has historically characterised TE in Greece. Qualitative data produced from the analysis of students’ handbooks revealed an increase in weakly classified modalities of knowledge organisation oriented to school professional contexts, such as inclusive learning, openness to community, innovative pedagogical practices, problem-solving and inquiry-based learning for future teachers (cf. Ball Citation2003). Moreover, courses on gender and environmental issues as well as ICT in education have been widely introduced in the contemporary Teacher Education curricula especially through OPEIVT II. At the same time, what is preserved as a strong pedagogical ‘voice’ in TE curricula is the content organisation of the practicum programmes which are kept strongly classified and framed, referring to forms of old professionalism (Sarakinioti Citation2012).

A crucial analytical question raised with reference to these findings is whether the knowledge base of TE in Greece has been thinning out and, if so, in what ways. Discussing our findings in relation to the critical literature on education knowledge (e.g. Beck and Young Citation2005; Beck Citation2008; Citation2009; Robertson Citation2013), we argue that the emerging forms of social regulation may put teachers’ practices and identities at risk because of the weakening of their disciplinary knowledge base and downgrading of the cognitive means they obtain in their initial training to act as highly specialised and autonomous professionals in the field. Moreover, the interventions of the “modernising project”, that is to say, the adjustments made in the effort to fulfil requirements for European funding, as well as the pressures for policies and practices of quality assurance and evaluation across the public sector and in education in particular, are leading to tighter control over teachers and institutions of teacher education. This means that issues previously left to professional judgment (teachers, academics) are now regulated through the introduction of codification and monitoring of processes and practices (cf., Dale Citation1989).

Given the complexity and fluidity in the objectives and the pressures exerted upon universities and TE departments in Greece concerning their study programmes, factors which to a certain degree may refer to trends of wider significance, what appears as a priority and necessity for the sociology of educational knowledge is not just to be concerned “with a social critique of knowledge but with identifying the conditions for knowledge”, in its production and acquisition (Young Citation2006, 21). Issues of identity reconfiguration appear to be urgent in research in order to understand the transformations occurring in the teaching profession. The various approaches prevalent in the study of teachers’ professional activity (e.g., the teacher as a researcher or activist), as discussed in the literature review section of this paper, may put limits on the debate as they are mostly based on political stances and ideological positions for describing the conditions, possibilities and needs of the school workforce. This paper contributes to such debates and concerns about TE through theoretically informed empirical research, focused on the analysis of boundary changes and transformations in knowledge-power relations, as a way of generating rigorous and systematic descriptions of the problems as well as possibilities carried by policies and practices aiming to enhance teachers’ competence and professionalism.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Antigone Sarakinioti

Antigone Sarakinioti holds a Ph.D. in Sociology of Education and Education Policy, awarded by the University of the Peloponnese, Greece. Her doctoral research was supported by the Greek ‘State Scholarships Foundation’ (IKY). Presently, she works in projects as independent researcher. Her main research interests and publications revolve around curricula and quality assurance in higher education, teacher education, European and global education policy, and discourse analysis.

Anna Tsatsaroni

Anna Tsatsaroni is Professor of Sociology of Education in the Department of Social and Educational Policy of the University of the Peloponnese, Greece. Her intellectual interests lie within social theory, the sociology of educational knowledge and practices, and sociological approaches to education policy. Her research and publications focus on the recontextualisation of knowledge in diverse contexts and sites of formal and informal education. Her published work appears in a range of international journals, contributing critical approaches to education policy and research.

Notes

1 Secondary school teachers are trained and qualified for the teaching profession in the undergraduate programmes of study offered by the university departments of science, humanities and social sciences, with subject specialisms in mathematics, physics, languages, foreign languages, etc. Their pedagogical training is a long standing issue in Greece. Recent legislation concerning their pedagogical competence is at an early stage of its implementation by the relevant departments. At present there is no research on the rate of expansion of such courses.

References

- Alexiadou N. The Europeanisation of education policy – researching changing governance and ‘new’ modes of co-ordination. Research in Comparative and International Education. 2007; 2(4): 102–116.

- Ball S. J. The teacher's soul and the terror of performativity. Journal of Educational Policy. 2003; 18(2): 215–228.

- Beck J. Governmental professionalism: reprofessionalising or re-professionalising teachers in England?. British Journal of Educational Studies. 2008; 56(2): 119–143..

- Beck J. Appropriating professionalism: restructuring the official knowledge base of England's ‘modernised’ teaching profession. British Journal Sociology of Education. 2009; 30(1): 3–14.

- Beck J., Young M. The assault on the professions and the restructuring of academic and professional identities: a Bernsteinian analysis. British Journal of Sociology of Education. 2005; 26(2): 183–197.

- Bernstein B. Young M. F. D. On the classification and framing of educational knowledge. Knowledge and control. New directions for the sociology of education. 1971; London: Collier-Macmillan Publishers. 47–69.

- Bernstein B. Class, codes and control. Volume 3. Towards a theory of educational transmissions. 1977; 2nd ed., London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Bernstein B. Class, codes and control, Volume IV. The structuring of pedagogic discourse. 1990; London: Routledge.

- Bernstein B. Pedagogy, symbolic control and identity. Theory, research, critique. Revised edition. 2000; New York: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers.

- Bernstein B. Morais A., Neves I., Davies B., Daniels H. From pedagogies to knowledges. Towards a Sociology of Pedagogy. The contribution of Basil Bernstein to Research. 2001a; New York: Peter Lang. 363–368.

- Bernstein B. Symbolic control: issues of empirical description of agencies and agents. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2001b; 4(1): 21–33.

- Biesta G. The future of teacher education: evidence, competence or wisdom?. RoSE - Research on Steiner Education. 2012; 3(1): 8–21.

- Bonal X., Rambla X. Captured by the totally pedagogised society: teachers and teaching in the knowledge economy. Globalisation, Societies and Education. 2003; 1(2): 169–184. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14767720303916.

- Bouzakis S., Tzikas Ch., Athanasopoulos K. Training of teachers for primary and preschool education in Greece. Volume B. The time of Pedagogic Academies 1933–1990. 1998; Athens: Gutenberg (in Greek).

- Cedefop. The shifting to learning outcomes. Policies and practices in Europe. Luxembourg. : Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. 2009. http://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/publications-and-resources/publications/3054 (Accessed 15-12-2014).

- CHEPS. The extent and impact of higher education curricular reform across Europe. Final Report, Parts 1 to 4. European Commission, Directorate-General Education and Culture. 2007. http://ec.Europa.eu/education/doc/reports/index_en.html (Accessed 24-4-2008).