Abstract

The focus of the current study is students’ perceptions of assessment and assessment practices. Assessment is understood as practices closely connected to the planning, enactment and evaluation of teaching and learning activities. The data derive from focus group interviews and dialogical meetings with students at a Swedish comprehensive school. Theories of assessment and validity are used as a framework to interpret and contextualise the data. An empirically developed interconnecting data analysis model is used as an analytical tool to connect students’ perceptions, assessment aspects and preconditions in a specific context. Our results indicate that students perceive assessment at different comprehension levels, categorised as performing, understanding and learning. Preconditions affect students’ possibilities of accessing assessment practices and using assessments to improve their performance. In this article we highlight the importance of taking student voice and preconditions into consideration when structuring accessible and meaning-making assessment practices that hold possibilities for enhanced learning.

Introduction

Using assessments to enhance learning has been a research area for a number of years (Black and Wiliam Citation1998, Citation2009; Hattie and Timperley Citation2007). Current research tends to focus on teachers’ assessment practices. Although the importance of student participation in assessment practices is often emphasised, few studies focus directly on students’ perceptions. Lately, however, studies focusing students’ voices have increased. Cowie (Citation2005), for example, found that students experience assessment as a complex activity in which they are participating in different ways. Depending on the way in which they were treated as learners, assessment had a different impact on their self-esteem and on the actions they considered beneficial. According to Harlen (Citation2012b) continued learning is dependent on students viewing themselves as learners and feeling that effort will lead to success. Cavanagh et al. (Citation2005) discovered that student perceptions of assessment build on five elements: alignment between goals and teaching and learning activities; authenticity; student involvement in assessment processes; transparency; and equal opportunity for all students. A Swedish research review indicates that students tend to view assessment as something done for someone else rather than for themselves and as something often stressful and negative for learning (Forsberg and Lindberg Citation2010). An OECD survey (Nusche et al. Citation2011) emphasised the need for further studies on students’ perspectives of assessment within a Swedish context.

This article discusses students’ perceptions of assessment in relation to assessment practices, learning and agency. The goal is to answer the following questions:

What student perceptions of assessment emerged in the study?

In what ways could these perceptions be conceptualised and utilised to enhance valid and accessible assessment practices?

We draw on a study conducted in a Swedish comprehensive school over a period of four years. In this, we use an interconnecting data analysis (IcDA) model that we have developed based on our empirical data. First, we contextualise the study and give a brief description of the theoretical framing and the methods used. Next, we discuss our findings using the IcDA model, and finally our study is considered in a broader research context.

Assessment in the Swedish context

The Swedish national curricula state that schools shall ensure that students develop increasing responsibility for their studies and enhance their ability to use self-assessment in relation to both educational and individual goals (Skolverket Citation2011). Teachers are obligated to use both formative and summative assessment. Formative assessment is communicated through oral and written dialogues (feedback) and in personal development plans aiming to enhance students’ knowledge and social development. Grading is part of teachers’ official mandate. From sixth grade onwards, teachers award individual grades each semester. The grades summarise the extent to which each individual student has reached the knowledge requirements in different subjects, as stated in the curriculum. The grades awarded in ninth grade determine what programme individual students are able to enter in upper secondary school.

Assessment

Assessment can be viewed as an interactive, dynamic and collaborative activity that is integrated into teaching activities and connected to classroom practice. Assessment affects our understanding of learning, the learner and what is supposed to be learnt (Moss, Girard and Haniford Citation2006). We define assessment as practices closely connected to planning, enacting and evaluating (teaching and) learning activities. What distinguishes these practices from learning processes is that assessment is used to explicitly clarify expectations on, and the quality of, performance with regard to specific learning objectives or a subject domain and to give guidance on how to proceed (Moss, Girard and Haniford Citation2006).

According to Harlen (Citation2012a), assessment in the learning process comprises summative and formative dimensions of purpose and use. All assessment starts with summative assessment, which is “a judgment which encapsulates all the evidence up to a given point” (Taras Citation2005, 468). Formative assessment is part of the key processes of learning, connected to the concepts of feed up – where am I going? – feedback – where am I now? – and feed forward – how do I proceed? (Hattie and Timperley Citation2007; Sadler Citation1989; Stobart Citation2012). The student needs to understand the quality of different achievements and what needs be done to close the gap between the current and desired performance (Black and Wiliam Citation1998; Hattie and Timperley Citation2007; Sadler Citation1989). However, assessment becomes formative only provided that the feedback received is used by the learner (Ramaprasad Citation1983; Scriven Citation1967; Wiliam Citation2011). In summary, seeking and interpreting evidence is summative, whereas showing the student the way forward is formative, thus making summative and formative assessment complementary rather than dichotomous (Harlen Citation2012a; Scriven Citation1967).

Assessment can be related to the concepts of purpose (why?), construct (what?), rubric (how?) and agent (who?) (Erickson Citation2013). The latter includes how different actors act and interact and how responsibility for assessment is shared, making it a central factor in assessment practices. The learning process can be supported by a reciprocal attitude concerning assessment (Black and Wiliam Citation2009; Harlen Citation2012b). Teachers need to understand students’ perceptions of assessment in order to create a participatory and high quality learning environment (Biggs and Tang Citation2011; Hayward Citation2012) that promotes excellence and equity. Consequently, teachers need to clarify what students are expected to do with their abilities and to create qualitative learning environments where assignments and methods stimulate these abilities and enhance student participation (Skolverket Citation2011). The pedagogical underpinnings can be described as students constructing meaning out of relevant learning activities. Teaching and learning activities, as well as assessment methods, therefore need to be constructively aligned with educational goals and specific learning outcomes (Biggs and Tang Citation2011).

Students’ engagement in the learning process and their participation in assessment practices are essential for their development of abilities, skills and knowledge (Biggs and Tang Citation2011; Black and Wiliam Citation1998, Citation2009; Schuell Citation1986; Stobart Citation2012). Leitch et al. (Citation2007) concluded that children are capable contributors in discussions on learning, teaching and assessment, provided they are given opportunities to participate in practice. Taylor, Fraser and Fisher (Citation1997) promoted so-called open discourses, where students are given opportunities to negotiate with teachers on learning activities, participate in the determination of assessment criteria, use self- and peer assessment, engage in collaborative and open studies with classmates and participate in developing practices.

Feedback

Feedback can be described as the function in assessment whereby the quality of performance and advice on improving performance is communicated (Harlen Citation2012a, Citation2012b; Taras Citation2005). Feedback is “generated within a particular system, for a particular purpose [and thus] has to be domain-specific” (Wiliam Citation2011, 4; cp. Moss, Girard and Haniford Citation2006). Whereas assessment is mostly related to purpose, construct and rubric – providing the broad basis for evaluating and documenting students’ performance – feedback focuses on agents, construct and use and is given in the course of the process – with the aim of enhancing learning (cp. Erickson Citation2013).

Feedback plays an important role for students’ understanding of performance and their abilities to enhance learning (Sadler Citation1989). Teachers use feedback to help students recognise quality and to lead learning forward. Thus, feedback should provide information about the gap between the current and desired performance and what can be done to “alter the gap in some way” (Ramaprasad Citation1983, 4). According to Stobart (Citation2012), feedback can be given at different levels. Feedback can be corrective (task level), aim to improve strategies (process level) or draw on students’ willingness to seek and use feedback, thus aiding self-assessment (regulatory level). Feedback at the self-level does not provide information leading learning forward.

For feedback to become effective it needs to be given at the right time, be linked to clarified goals, help students understand quality and give information and strategies on how to proceed (Hattie and Timperley Citation2007; Stobart Citation2012). To improve learning, feedback must be used within the instructional system where it was given (Wiliam Citation2011). Furthermore, students need to consider it worthwhile and be motivated to use feedback (Stobart Citation2012; Throndsen Citation2010). According to Harlen (Citation2012b), the best way to promote learning is to make sure that students are actively involved in the feedback process.

Construct validity in formative assessment

Validity theories give guidance on whether interpretations, decisions and actions in assessment practices are valid (Moss, Girard and Haniford Citation2006). We draw on the overall concept of construct validity that is used to validate empirical data against a particular hypothetical construct. Construct validity was outlined by Cronbach and Meehl (Citation1955) and later specified by Cronbach (Citation1971), who stated that “[whenever] one classifies situations, person, or responses, he uses constructs” (Cronbach Citation1971, 462). Messick (Citation1989) added an ethical dimension to construct validity, arguing that validity and values – both imperatives – cannot be separated. Valid assessment thus needs to be based on empirical evidence and theoretical logics that support suitable and sufficient inferences and actions (Stobart Citation2012) and include impact and value implications (Erickson Citation2013; Messick Citation1989).

Hence validity is about seeing what supports learning and what does not (Stobart Citation2012). Valid formative assessment is achieved when the intention to improve learning leads to real improvement. Validity also concerns how effective assessment is in making judgments of the subject domain in general (Moss, Girard and Haniford Citation2006). For assessment to be valid, both students and teachers need to understand the target domain and what it means to manage that domain at different quality levels. If teachers fail to clarify the goals and explain quality, validity is undermined. If students lack understanding of the learning objectives, feedback has less chance to lead to improvement.

Kane (Citation2006) relates validation to the intent to improve learning, whereas validity is dependent on how well intentions are achieved. Within this study, validation is used to view the intention to enhance learning through an assessment practice accessible for students (Kane Citation2006). The validity framework highlights opportunities and constraints that affect students’ possibilities to access assessment practices. The strength of constructive alignment is defined by how well teaching and learning activities and assessment methods are linked to the learning objectives. Validation of assessment practices involves the degree to which students are given possibilities to reach the learning objectives within those practices, as well as the intended and non-intended impact of assessment on students (Crooks, Kane and Cohen Citation1996; Erickson Citation2013; Kane Citation2006, Citation2013; Messick Citation1989).

Methodological approach

The current study aimed to explore and contribute to an enhanced understanding of students’ perspectives of assessment and how this understanding could be used as a basis for designing practices. Both students and teachers participated in the overall study; however, students are the primary agents in this article. We used action research as our overarching methodological frame. Throughout the study, we strived for collaboration in data production and preliminary analyses based on democratic principles – such as the importance of the individual voice, mutual respect and the richness in diversity of experiences and knowledge (Wennergren Citation2012).

Two dialogical data collection methods were used – one more structured and question-driven (focus group interviews) and one more dynamic and process-driven (dialogical meetings). In the dialogical meetings, students exchanged experiences of assessment practices while describing their understanding of assessment. This gave them and the researcher (the first author) opportunities to build a common understanding that contributed to ideas on how to design practices. During the study, ‘communicative spaces’ (Habermas Citation1996, cp. Taylor, Fraser and Fisher Citation1997), such as debriefing and analysis meetings, were designed to enhance students’ agency and their access to the research process. The communicative spaces gave students opportunities to participate in the preliminary analysis and give input to the continuing study, thereby making the research process more transparent and collaborative.

The methodological frame facilitated understanding of students’ perceptions of assessment practices and of the context in which practices were included. It also enhanced students’ abilities to actively participate in dialogues on assessment practices and in attempts to develop assessment practices (cp. Carr and Kemmis Citation1986; Rönnerman and Wennergren Citation2012). Through collaboration, a relationship between thinking about practice and an opportunity to act more consciously in practice was established (cp. Rönnerman Citation2012).

Sample and data collection

The study was conducted at a comprehensive school, with students aged 11–16, in a medium-sized Swedish town over a period of four years. The empirical data derive from seven focus group interviews with 29 students (2010) and 18 dialogical meetings, divided into three rounds, with 25 students participating in each round (2012–2013). Students from two classes were asked to participate in the study, and focus group interviews and dialogical meetings were carried out with all students who wished to participate. Participation was evenly distributed between boys and girls. The students’ performance varied in quality, as did their motivation for studying, which generated a wide range of experiences and understandings.

Focus group interviews were used initially to identify students’ experiences and perceptions of assessment. Seven interviews were conducted with students in grades five and seven. The interviews were semi-structured and aided by initial, comprehensive and in-depth questions, originating from a predesigned interview guide. During the interviews, the researcher acted as the moderator of the ongoing dialogue and introduced new aspects when necessary. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed.

Subsequent studies used dialogical meetings to capture thoughts, possibilities and difficulties with regard to assessment practices. One round of dialogical meetings was conducted with students in grades seven and eight (2012) and two rounds with the same students the following school year (2012–2013). The meetings focused on various aspects of assessment and collaboration in assessment practices (). Themes were selected from an ongoing, parallel observational study, which also provided complementary empirical data. Narratives and photos from observations as well as pedagogical plans were used to initiate the dialogues. Follow-up questions or additional narratives and photos were introduced when necessary as further inspiration and to add depth to the conversations. Mind mapping served as a supportive method to summarise and visualise ongoing dialogues (Gannerud and Rönnerman Citation2005). Each session was audio recorded and later transcribed.

Table 1. Data collection and analysis specifications

Processing and analysing data

Data from the focus group study were analysed, in 2010, using content analysis (Graneheim and Lundman Citation2004). An analysis table was constructed and meaningful units were chosen. Each unit was condensed to encircle the core of the text and was then abstracted into sub-themes and themes. A complementary mind map aided verification of the consistency between meaning units and themes. Three hierarchically distinct qualitative categories of students’ perceptions of assessment emerged – henceforth referred to as performing, understanding and learning. Preliminary findings were discussed with students and teachers and thereafter used in a teacher–student project on developing assessment practices in which the researcher (first author) acted as facilitator.

In 2013, data from interviews together with additional data from dialogical meetings were analysed using Stobart's validity framework for formative assessment (personal communication, November 16, 2012). The validity framework consisted of such aspects as clarity of goals, diagnosis and feedback (). It highlighted opportunities and potential threats to validity and aligned these threats with both verbal and physical actions within these practices. By connecting assessment aspects with students’ statements on assessment practices, various preconditions that influence the shaping of a practice appeared.

Table 2. Analyses based on Stobart's validity framework showing assessment aspect (Personal communication, November 16, 2012)

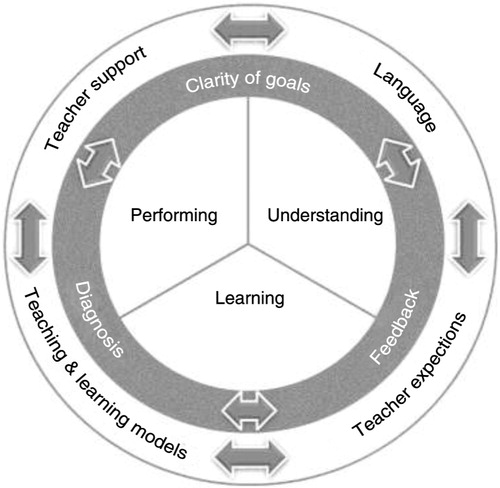

To enhance the understanding of how the categories that emerged during the content analysis were related to preconditions in practice and to assessment aspects, an empirically derived model was designed and used as an operative model in the overall analysis. The IcDA model () draws on a construct consisting of validity theories (Crooks, Kane and Cohen Citation1996; Kane Citation2006, Citation2013; Stobart Citation2012) and assessment research that forwards ideas of mutual understanding of goals, dialogical classrooms, domain-specific feedback and the importance of teacher–student collaboration when designing assessment practices that support learning (Black and Wiliam Citation2009; Harlen Citation2012b; Schuell Citation1986).

The IcDA model is constructed as three encircling fields. The inner field consists of the three identified categories – performing, understanding and learning – whereas the middle field describes fundamental assessment aspects – diagnosis, clarity of goals and feedback. The outer field shows the preconditions highlighted by students as relevant for practice – teaching and learning models, teacher support, teacher expectations and language. Both outer fields are movable to illustrate how different factors can affect each other. The model is influenced by the visual form and interconnectedness of Ax and Ponte's model for unity of action and unity of research (Citation2010, 38).

In summary, the IcDA model combined the categories and preconditions emerging from the analyses of the interview data with the assessment aspects from Stobart's validity framework. In the overall analysis, it was used to understand the connections between students’ perceptions, preconditions in practice and assessment aspects (as presented in current research) and to validate the assessment practices described. The latter served as a basis to zoom in on aspects that may be pivotal when designing accessible and reciprocal assessment practices.

Findings

In the following section, students’ experiences and understanding of assessment are presented under headings that are equivalent to the categories in the IcDA model. Assessment aspects from Stobart's validity framework and preconditions – which form and affect assessment practices – contribute to clarifying students’ statements.

When translating statements into English, we have strived to make the translated statements as similar as possible to the original statements, but they should nonetheless be regarded as narratives rather than quotes. The narratives are based on everyday language and have been transcribed with written language conventions.

Performing

Statements categorised as performing were closely related to the summative function of assessment and mostly concerned evaluation of the outcomes of assignments and exams. Most students related assessment on assignments to facts on specific topics and to personal goals on how to raise performance by eliminating errors.

Some students made a direct link between assessment, tests and grades, explaining that some teachers assessed performance based on the last test that semester, not on the students’ performance throughout the semester, which they thought affected the way some of their classmates related to their learning process.

Some students in our class say, “This is not the last exam, so why should I study for it?” They might have gotten that idea from the teacher. If they have the notion that the teacher only assesses the final exam, then they think they don't have to do all the exams. (Student, seventh grade)

Some students described assessment as consisting mostly of praise – “Well done!” – or exhortations – “You can do better!” Students often perceived this kind of feedback, for example “Excellent,” as meaningless, because it did not give advice on how to proceed. “It should have read: ‘Excellent! I can see that you have made progress. To reach further you need to do this and this,’” one student explained. Self-level feedback also made it difficult for students to understand whether it was their behaviour/actions or performance that was being assessed.

There are some teachers who say they assess lessons, though it doesn't seem so. If a teacher says that it is important to be active in class and I am active but perform less well on an exam, I will still get a lower grade. But why? He said I was active in class. (Student, eighth grade)

When asked questions about educational goals, the students discussed how clarified goals could have been helpful when preparing for a test and how that would affect their possibilities to reach different qualitative levels of achievement. They believed that clarified goals would have helped them recognise what they were supposed to work with, as well as the quality level of their current performance. These statements often connected rubrics to specific facts within a subject, not to learning objectives.

The students also emphasised that teachers’ expectations were important. They perceived that teachers had different expectations regarding what results different students could reach, demanding more from high performing students and assessing their assignments more strictly. However, both high and low performing students considered the ‘other group’ as privileged, getting all the help and attention from the teachers. Most students considered both teacher support and teacher expectations as essential preconditions for raising performance.

Understanding

Statements categorised as understanding were closely connected to clarity of goals and perception of feedback, thereby relating more directly to the formative functions of assessment. Statements ranged from ‘grasping’ (e.g. the connection between educational goals and teaching and learning activities) to ‘realising’ (e.g. what to do to improve an assignment). However, understanding did not automatically generate an active use of assessment and feedback.

In general, students expressed problems comprehending what the classroom activities were aimed at. They described how teachers clarified goals by highlighting direct wordings from the curriculum. Many students had trouble interpreting these wordings, relating them to classroom activities and understanding how to improve their performance.

When we started the new semester, the teachers talked a lot about the new curriculum [Lgr11]. But in fact I didn't understand anything. They said that these are the goals you shall be working with and we answered “OK,” but it was not clear enough. We didn't understand what we were supposed to improve. (Student, seventh grade)

When we start a new area [TLU], teachers should be going through the criteria and explaining what we must do to reach the goals. When we suggest this to the teachers, they say that we don't have the entire school year to discuss goals. In my opinion we should reduce our workload, assignments and tests and such […] to make sure we understand the goals [otherwise the knowledge] won't last. (Student, seventh grade)

Feedback was an aspect frequently mentioned as important for understanding and learning. Teacher feedback was seen as an asset for raising performance. However, students voiced different opinions on the feedback given. Some students perceived that they were given feedback on all assignments and exams, whereas others expressed that not all teachers gave feedback.

Teachers should give us back our tests and say: “You could have done this better. To achieve a higher grade, you should do this and this and this.” That would certainly have gotten many to improve their performance. Because then you know where you are. Some students don't know what to do. (Student, eighth grade)

To be able to improve and learn from mistakes, students said they needed time to develop their work after receiving feedback. According to the students, time dedicated to working with feedback, for example on writing assignments, was not common. Although some of them regarded processing texts as boring, they agreed that working with an assignment based on teacher feedback might be a good way to improve performance.

It sounds boring [but] you can always improve your text if it wasn't very good. “You can improve your text,” my teacher said. And I thought: “Why not!” And I did it and there was nothing wrong with that. (Student, eighth grade)

Some statements described diagnosis as a way of understanding what they already understood and what they needed to keep practising. They made a connection between current knowledge and future needs. Those students regarded exams as places for rehearsing knowledge they considered would be developed later on.

You have to look at the exam and see what you did wrong. Then you learn more. In the eighth and ninth grade I think we will go back and work more on this, and then it's a good idea to keep your old exams so you can see what you have learned and not learned. (Student, seventh grade)

What distinguished these statements from those categorised as ‘performing’ was that students discussed aspects of understanding or learning. The exams were used as resources for understanding the subjects or what they needed to do to improve.

Understanding was also described as underpinned by teaching and learning models used in the classroom. Teachers who invited students into assessment practices by discussing goals and TLUs, and teachers who used the students’ questions as a starting point for clarification dialogues, were highly appreciated by the students. Their lessons were regarded as those where expectations on students were high and where the students gained a high degree of teacher support.

Learning

Although statements categorised as understanding involved a cognitive dimension, they also expressed an instrumental view of understanding and the requirements of contextualisation. Statements classified as learning were less contextualised, indicated a more effortless understanding of assessment and carried elements of metacognition. Some statements pointed to an internalisation of the assessment, which generated knowledge about improvements.

Some of the students made clear connections between the importance of clarified goals and learning potential, talking about how understanding criteria was the basis for knowing how to develop assignments and how to judge quality on performance. Some students claimed that if they did not understand criteria, chances were that they would just learn facts by heart, which they did not consider as learning. Clarifying goals was considered to promote understanding and learning. Learning something without receiving an explanation made it hard to grasp, students said. The major constraint was the language used to describe learning objectives.

The words are very difficult, so I don't understand the meaning of the text. I just kind of read through it, but I don't understand what it says. […] If it had just been simpler words, then I would have understood it, I would have bothered. But ‘understanding the relationship,’ that is really hard to comprehend. (Student, fifth grade)

Students considered the language too advanced and expressed frustration that what was supposed to aid their learning was more difficult to understand than the learning objective itself. They agreed that the most important aspect to help them improve their learning was feedback that guided them in their future process.

I need to improve my performance from where I am right now. To know what to improve, teacher feedback and constructive criticism are the most important things. (Student, eighth grade)

Consequently, feedback should consist of both feedback and feed forward in relation to reaching higher qualitative performance, students said (although not using those precise words). Depending on what type of language was used, and on when it was written, students used or did not use feedback.

[We are given] too little feedback. Sometimes just half a sentence. Teachers write things like “Do a little bit more” and nothing else […] That's no fun because you have nothing else to strive for. (Student, seventh grade) If they'd written more, I may have improved my learning. (Student, seventh grade)

Feedback that came too late or was poor in content was not regarded as supporting learning or being applicable when improving tasks or raising results. Students explained that they learnt things when they were given time to use feedback when processing assignments. By working in different ways with texts and assignments, you develop “knowledge that stays,” they explained. To discuss criteria and goals with peers was considered a way of increasing students’ responsibility for their own learning and activating them as resources for each other. “Teachers should have greater demands on us,” one student concluded.

Statements regarding learning were scarce compared to statements of performing and understanding. Most students had difficulties verbalising the relationship between assessment and learning. When discussing what can be characterised as formative aspects of assessment, most statements were related to suggestions on what could be done in practice rather than descriptions of what was actually done.

Discussion

In the following section, we discuss our findings in relation to a construct of valid assessment practices. This construct builds on prior research that brings forth the importance of clarified goals, feedback at the process or regulatory level and comprehensive suggestions on how to proceed. Valid assessment practices are dependent on student participation (Kane Citation2006) and student understanding of assessment (Moss, Girard and Haniford Citation2006; Stobart Citation2012). Access and agency in assessment practices will therefore be discussed with reference to preconditions. Preconditions that affect assessment practices have been highlighted before, for example by Hayward, Priestley and Young (Citation2004) and Carless (Citation2005). However, these studies discuss preconditions from a teacher perspective. This study aims to add to the field by bringing in students’ perspectives on preconditions.

Our initial analysis indicates that students’ perception of assessment can be categorised as performing, understanding and learning. Although these categories overlap to some extent, we will separate them to clarify some key findings.

Our findings show that students’ understanding of and access to assessment practices are dependent on relevant teaching, learning and assessment activities, student-friendly language related to goals and feedback and relationship with teachers (cp. Cavanagh et al. Citation2005). This correlates with Cowie's (Citation2005) findings describing that the student–teacher relationship (which teachers students ‘get along with’) is somewhat connected to the language teachers use in feedback. In our study the student–teacher relationship is connected to personal, social and democratic conditions.

Regarding performing, teacher expectations were found to be the main precondition and diagnosis the most common aspect. Our analyses indicate that the purpose of diagnosis and the link between diagnosis, goals and learning were unclear to the students. Students expressed a general wish to improve the quality of their performance but seldom related quality to specific goals, learning objectives or skills to be developed. They often characterised facts as the learning objectives. Students’ statements concerning the need for clarity of goals might be understood as a lack of explicit connection between performing and teaching and learning models. When it came to assessment as understanding, all aspects were represented. In these statements students often displayed a rather instrumental view on how understanding goals, criteria and feedback could create opportunities for learning. At the same time, they showed understanding of a development potential regarding performance. This understanding was found in statements concerning teacher feedback and processing assignments. It also occurred when students talked about diagnosis. Some students made distinctions between knowledge that was confirmed (‘where you are’), knowledge that could be improved (‘what you must continue to work with’) and knowledge that needed to be developed and added (‘building knowledge that you at this point do not have’). By making these distinctions, assessments that did not contain formative functions could still be useful for students when developing their performance. How these aspects were perceived was dependent on the preconditions: language, teaching and learning models, and teacher support (cp. Cowie Citation2005; Harlen Citation2012b). Our findings indicate that the strength of the preconditions and the relationship between them determined whether the student gained a more superficial understanding or whether understanding led to learning. As preconditions, teaching and learning models and language were decisive for learning, according to our analyses. These preconditions connect the categories learning and understanding. As a metacognitive function, learning tends to be more abstract, thus making it harder for students to link performance and teacher assessment to the learning process. According to our findings teaching and learning models did not always support an active learning process. The students in our study expressed difficulties understanding how performance on a single assignment was related to the learning process, in specific subjects, or to learning in general. This might indicate practices with weak constructive alignment (Biggs and Tang Citation2011) and low validity (Kane Citation2006). Clarifying expectations for a specific assignment in relation to the learning objective and the subject domain may be pivotal for student understanding and engagement in assessment practices (Moss, Girard and Haniford Citation2006).

Prior research presents clarity of goals and feedback as two key aspects affecting learning (Moss, Girard and Haniford Citation2006; Wiliam Citation2011). In our study, preconditions as teaching and learning models, and teacher support, appeared significant for the way students understood and used feedback. This became noticeable when students talked about lessons where they were given the opportunity to discuss feedback with peers and teachers and to process texts based on feedback. Feedback at the task level was categorised as either performing or understanding, depending on how feedback was formulated and to what extent the students were able to use feedback to improve assignments. Feedback given at the process level was appreciated by the students and seen as an opportunity for enhanced understanding as well as learning. This type of feedback was categorised as either understanding or learning, depending on whether it led to improvement of an assignment or helped students move their learning forward. Our analysis indicates that differences between the categories understanding and learning seem to lie in the degree of student autonomy and abilities for metacognition. Statements categorised as learning to a higher degree concern the quality of performance and how performance can be developed. This may have implications for how teaching and learning activities are arranged and how work with enhancing metacognitive abilities can be developed, for example by using self-assessment. Hayward's (Citation2012) findings show that students view peer assessment as a fruitful way to enhance understanding and learning. Expanding the spaces for peer assessment may therefore be a viable way to enable students to become active learners.

The most considerable threats to validity can be found in processes that undermine constructive alignment, since they affect students’ abilities to understand goals, learning objectives, the quality of their own work and feedback. As shown by Moss, Girard and Haniford (Citation2006) and Wiliam (Citation2011), assessment that enhances learning must clarify learning intentions and provide domain-specific feedback that moves learning forward (cp. Sadler Citation1989). Separating contextual understanding from learning may therefore lead to more adequate choices of assessment methods, emanating from students’ needs. Summative and formative functions are found in all categories, which in itself clarifies the complexity that needs to be addressed when designing valid assessment practices.

Learning is a proactive process where learners act as agents that are capable of using effective learning strategies to reach their goals (Määttä, Järvenoja and Järvelä Citation2012). Thus, threats to validity can be related to activities, language and relationships. For teaching and learning models to support an active learning process, students need to be engaged in how interpretations, decisions and actions relate to one another (Moss, Girard and Haniford Citation2006). Agency and ‘life-long learning’ are stressed in the Swedish Education Act (SFS Citation2010:800) and the curriculum (Skolverket Citation2011), where it is related to democratisation processes and a global citizenship. Hence, in a global world, local school practices become important as arenas for practising skills and abilities needed later on in life (cp. Salo and Rönnerman Citation2014). Creating valid assessment practices, where activities give meaning and relevance to students, goals and feedback are expressed in student-friendly language, and relations build on reciprocity, may be crucial for enhancing student learning (cp. Cavanagh et al. Citation2005; Gao Citation2012). Moss, Girard and Haniford (Citation2006) discussed how valid interpretations, decisions and actions take place in practice, where access to communicative spaces is decisive for what is learnt. The results from a Finnish study on student efficacy (Määttä, Järvenoja and Järvelä Citation2012) indicate that reciprocal meaning-making supports students’ way of thinking and learning. Similar indications are given by Christensen (Citation2008), who reported on successive, formative dialogues between teacher and students in a Danish school. Our study shows that even though students discuss several assessment practices – related to different subjects and teachers – and projects within these practices – for example using feedback to improve assignments – language is a recurring constraint when accessing these practices. Our findings indicate that difficulties engaging in communicative spaces make it hard for students to gain access to assessment practices, which constitutes a constraint on their learning process. Leitch et al. (Citation2007) showed that students can provide fruitful contribution if they are given access to and agency in practice. Providing communicative spaces, for example in open discourses, as suggested by Taylor, Fraser and Fisher (Citation1997), may therefore prove to be decisive for students’ accessibility to assessment practices.

A valid assessment practice includes an ethical dimension, taking into consideration that validity and values cannot be separated (Messick Citation1989). Our analysis highlights the fact that not taking students’ perceptions as a basis for structuring accessible and meaning-making assessment practices may lead to unintended negative impact on student learning. We understand and define valid assessment practices as underpinned by pedagogical and didactical ideas based on ethical and democratic values (Moss, Girard and Haniford Citation2006). Democracy per se depends on richness of voices and agency. A stronger focus on student voice may be a way of bringing these ethical and reciprocal aspects into research on assessment practices.

Concluding remarks

The current study aims to enhance our knowledge of what affects students’ understanding of assessment and their agency in assessment practices. No general conclusions can be drawn from a small-scale research study. The use of interviews and dialogues as methods of gathering data also calls for a consideration of the compliance effect. In the current, longitudinal study, the students and the researcher (the first author) developed communicative spaces, where assessment was discussed using mutual language. Key concepts of assessment, brought into this communicative space by the researcher, may have influenced the students’ ways of expressing their thoughts during the 4-year study. Nonetheless, the study identifies the complexity of assessment practices by bringing in student voices. In addressing how different factors affect what kind of “interpretations, decisions and actions” (Moss, Girard and Haniford Citation2006), students are able to make and take based on the assessment given, the study may help readers appreciate that assessment methods need to be chosen based on a solid understanding of students’ comprehensions and needs and of preconditions in specific practices.

In our analysis, the IcDA model was a beneficial operative model enhancing the relationship between conceptualised perceptions, assessment aspects and preconditions. However, the usefulness of the model needs to be validated in other research studies where it can be developed further.

More research on student perspectives in assessment is called for. Further research may develop a more complete understanding of students’ perceptions of assessment by sampling a larger body of students or using different methods; zooming in on different school levels or on assessment within specific subjects; and by addressing preconditions from both students’ and teachers’ perspectives.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lisbeth Gyllander Torkildsen

Lisbeth Gyllander Torkildsen is a PhD student at the Department of Education and Special Education at the University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden. Her main research interest is students’ and teachers’ mutual assessment practices. With a methodological focus on action research, another main research interest is school development based on needs within specific contexts. Email: [email protected]

Gudrun Erickson

Gudrun Erickson is a professor of education at the Department of Education and Special Education, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden. Her main research focus is assessment within language, in particular students’ contributions to the development of good assessment practices. Email: [email protected]

References

- Ax Jan, Ponte Petra. Moral issues in educational praxis: a perspective from pedagogiek and didactiek as human sciences in continental Europe. Pedagogy, Culture & Society. 2010; 18(1): 29–42. [PubMedAbstract] [PubMedCentralFullText].

- Biggs John B., Tang Catherine. Teaching for quality learning at university. 2011; Maidenhead, UK: Open University Press. 4th ed.

- Black Paul J., Wiliam Dylan. Assessment and classroom learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice. 1998; 5(1): 7–73.

- Black Paul, Wiliam Dylan. Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability. 2009; 1(21): 5–31.

- Carless David. Prospects for the implementation of assessment for learning. Assessment in Education. 2005; 12(1): 39–54.

- Carr Wilfred, Kemmis Stephen. Becoming critical. Education, knowledge and action research. 1986; London: Routledge Falmer.

- Cavanagh Robert, Romanoski Joseph, Fisher Darrell, Waldrip Bruce, Dorman Jeffery. Measuring student perceptions of classroom assessment. 2005. in Jeffery, R. and Shilton, W. and Jeffery, P. (ed), AARE 2005 International Education Research Conference - Creative Dissent: Constructive Solutions, (2-12). NSW: AARE Inc. Permanent Link: http://espace.library.curtin.edu.au/R?func=dbin-jump-full&local_base=gen01-era02&object_id=156244 (Accessed 2005-11-27)..

- Christensen Torben S. Et evalueringsexperiment: Fagligt evaluerende lærer-elevsamtale [An evaluation experiment: content evaluating teacher-student talks]. Evalueringens spændingsfelter [The tensions of evaluation] . 2008; Århus: Forlaget KLIM. 137–175. Karin Borgnakke (ed.).

- Cowie Bronwen. Pupil commentary on assessment for learning. The Curriculum Journal. 2005; 16(2): 137–151.

- Cronbach Lee J. Test Validation. Educational Measurement. 1971; Washington, DC: American Council on Education. 443–507. 2nd ed. Robert L. Thorndike (ed.).

- Cronbach Lee J., Meehl Paul E. Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin. 1955; 52(4): 281–302. [PubMed Abstract].

- Crooks Terry J., Kane Michael T., Cohen Allan S. Threats to the valid use of assessments. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice. 1996; 3(3): 265–285. [PubMedAbstract] [PubMedCentralFullText].

- Erickson Gudrun. Even tests…!. Language, Football and All That Jazz. A Festschrift for Sölve Ohlander. 2013; Göteborg: University of Gothenburg. Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis; Gothenburg Studies in English 100. 83–97. Gunnar Bergh, Rhonwen Bowen and Mats Mobärg (eds.).

- Forsberg Eva, Lindberg Viveca. Svensk forskning om bedömning – en kartläggning [Swedish research on assessment – a survey]. 2010; Stockholm: Vetenskapsrådet.

- Gannerud Eva, Rönnerman Karin. Studying teachers’ work through mind-maps. New Zealand Journal of Teachers′ Work. 2005; 2(2): 76–82.

- Gao Minghui. Classroom assessment in mathematics: high school students’ perceptions. International Journal of Business and Social Science. 2012; 3(2): 63–68.

- Graneheim Ulla H., Lundman Berit. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today. 2004; 24(2): 105–112. [PubMed Abstract].

- Habermas Jürgen. Between facts and norms: contributions to discourse theory of law and democracy. 1996; Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Harlen Wynne. On the Relationship between Assessment for Formative and Summative Purposes. Assessment and Learning. 2012a; London: Sage. 87–102. 2nd ed. John Gardner (ed.).

- Harlen Wynne. The role of assessment in developing motivation for learning. Assessment and Learning. 2012b; London: Sage. 171–183. 2nd ed. John Gardner (ed.).

- Hattie John, Timperley Helen. The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research. 2007; 77(1): 81–112.

- Hayward Louise. Assessment and learning: the learner's perspective. Assessment and Learning. 2012; London: Sage. 125–139. 2nd ed. John Gardner (ed.).

- Hayward Louise, Priestley Mark, Young Myra. Ruffling the calm of the ocean floor: merging practice, policy and research in assessment in Scotland. Oxford Review of Education. 2004; 30(3): 397–415.

- Kane Michael. T. Validation. Educational measurement. 2006; Westport, CT: American Council on Education/Praeger Publishers. 17–64. 4th ed. Robert L. Brennan (ed.).

- Kane Michael. T. Validating the interpretations and uses of test scores. Journal of Educational Measurement. 2013; 50(1): 1–73.

- Leitch Ruth, Gardner John, Mitchell Stephanie, Lundy Laura, Odena Oscar, Galanouli Despina, Clough Peter. Consulting pupils in assessment for learning classrooms: the twists and turns of working with students as co-researchers. Educational Action Research. 2007; 15(3): 459–478.

- Messick Samuel A. Validity. Educational Measurement. 1989; New York: American Council on Education/Macmillan. 13–103. 3rd ed. Robert L. Linn (ed.).

- Moss Pamela, Girard Bryan J., Haniford Laura C. Validity in educational assessment. Review of Research in Education. 2006; 30(1): 109–162.

- Määttä Elina, Järvenoja Hanna, Järvelä Sanna. Triggers of students’ efficacious interaction in collaborative learning situations. Small Group Research. 2012; 43(4): 497–522.

- Nusche Deborah, Halász Gábor, Looney Janet, Santiago Paulo, Shewbridge Claire. OECD reviews of evaluation and assessment in education – Sweden. 2011; Paris: OECD.

- Ramaprasad Arkalgud. On the definition of feedback. Behavioral Science. 1983; 28(1): 4–13.

- Rönnerman Karin. Vad är aktionsforskning? [What is Action Research?. Aktionsforskning i praktiken – förskola och skola på vetenskaplig grund. [Action Research in Praxis – pre-school and school on scientific ground] . 2012; Lund: Studentlitteratur. 21–40. Karin Rönnerman (ed.).

- Rönnerman Karin, Wennergren Ann-Christine. Vetenskaplig grund och beprövad erfarenhet [Scientific ground and proven experience]. Aktionsforskning i praktiken – förskola och skola på vetenskaplig grund [Action Research in Praxis – pre-school and school on scientific ground] . 2012; Lund: Studentlitteratur. 221–228. Karin Rönnerman (ed.).

- Sadler Royce. Formative assessment and the design of instructional systems. Instructional Science. 1989; 18(2): 119–144.

- Salo Petri, Rönnerman Karin. The Nordic Tradition of Educational Action Research – In the Light of Practice Architectures. Lost in practice: Transforming Nordic Educational Action Research. 2014; Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. 53–71. Karin Rönnerman and Petri Salo (eds.).

- Schuell Thomas J. Cognitive conceptions of learning. Review of Educational Research. 1986; 56(4): 411–436.

- Scriven Michael. The methodology of evaluation. American Educational Research Association Monograph Series on Curriculum Evaluation, Vol. 1: Perspectives of Curriculum Evaluation. 1967; Chicago: Rand McNally. 39–83. Ralph W. Tyler, Robert M. Gagne & Michael Scriven (ed.).

- SFS. Skollag [Education Act]. 2010:800; Stockholm: Utbildningsdepartementet.

- Skolverket. Läroplan för grundskolan, förskoleklass och fritidshem 2011 [Curriculum for the comprehensive school, preschool class and the recreation centre] . 2011; Stockholm: Skolverket.

- Stobart Gordon. Validity in formative assessment. Assessment and learning. 2012; London: Sage. 233–242. 2nd ed. John Gardner (ed.).

- Taras Maddalena. Assessment – Summative and formative – Some theoretical reflections. British Journal of Educational Studies. 2005; 53(4): 466–478.

- Taylor Peter C., Fraser Barry J., Fisher Darrell L. Monitoring constructivist classroom learning environments. International Journal of Educational Research. 1997; 27: 293–301.

- Throndsen Inger. Lærerens tilbakemeldinger og elevenes motivasjon [The teacher's feedback and the student's motivation]. Nordic Studies in Education. 2010; 31: 165–179.

- Wennergren Ann-Christine. På spaning efter en kritisk vän [In search of a critical friend]. Aktionsforskning i praktiken – förskola och skola på vetenskaplig grund [Action Research in Praxis – pre-school and school on scientific ground] . 2012; Lund: Studentlitteratur. 71–88. Karin Rönnerman (ed.).

- Wiliam Dylan. What is assessment for learning?. Studies in Educational Evaluation. 2011; 37(1): 3–14.