Abstract

The paper discusses the identity-building power and motivational force of patriotism. The basic idea underlying the discussion is that far from being a mere irrational and destructive force, patriotism is an expression of ‘existing human social identity.’ Thus, it argues that rather than dismissing patriotism altogether as an undesirable and/or irrational phenomenon, we need to understand how to discriminate between alternative forms of patriotism while investigating what constitutional reforms might be required to support those forms of patriotic identification that are morally desirable. I argue that to flourish, desirable forms of patriotism (what I call Ethical Patriotism) require a political milieu where forms of subsidiarity, functional representation and local participation combine to produce a more democratic and decentralized system of governance. Applied to a post-national polity like the EU, this conclusion invites to rethink the European constitutional project so as to make it less elitist and more open to influence and participation from below.

Introduction

The paper discusses the identity-building power and motivational force of patriotism vis-à-vis cosmopolitan value-systems. First, I summarize various theoretical perspectives that advocate patriotism as a set of beliefs supporting feelings of loyalty and alliance. All these perspectives share the idea that patriotic identification represents a positive social force which exercises a deep influence on individual action. This stress on identity, rather than interests, has inspired the communitarian critique of liberal theories and helped develop a civic patriotic perspective which harks back to a republican political tradition. Here, I question the epistemology of the self upon which some of these perspectives often rest and highlight their failure to distinguish and discriminate between alternative modes of patriotic identification. Second, I advance a taxonomy of patriotisms that cuts across the traditional civic/ethnic divide and identifies four distinct ideal-types of patriotism: Ethical, Protective, Hegemonic, and Jingoistic. Each of these ideal-types rests upon a distinctive conception of identity and upholds diverse value-systems. I maintain that any defense of patriotism vis-à-vis cosmopolitan visions entails assessing the relative desirability of these ideal-types. I contend that while the Protective ideal-type is merely reactive, Hegemonic and Jingoistic modes of patriotism tend to promote selves and institutions that are incompatible with the ideals of self-determination they claim to advocate. Finally, I discuss the institutional milieu more conducive to an Ethical form of patriotic identification. I argue that to flourish, the Ethical ideal-type requires a political milieu where forms of subsidiarity, functional representation, and local participation combine to produce a more democratic and decentralized system of governance. A democratic polity of this type would, in my opinion, endorse social change without generating troublesome Protective patriotic movements and would, therefore, be able to resist the maneuvering of political elites with ethnic agenda and hegemonic aspirations. Applied to a multicultural polity like the EU, this conclusion suggests the need to rethink the European constitutional project so as to make it less elitist and more open to influence and participation from below.

2 Patriotism, identity, and compliance

As a set of beliefs and feelings of loyalty and allegiance, patriotism is related to people's identity and exercises a deep influence on individual action. It is through patriotic attachment that membership can be defined, social choice can acquire consistency and voluntary compliance be relied upon. Patriotism is, in other words, a social force that can keep separate individual together by turning an array of self-concerned agents into a community and a collection of distant groups into a nation. The first systematic attempt to analyze patriotism as a source of identity and motivational force comes from political theory and Rousseau's work in particular. For Rousseau, patriotism is the linchpin between the voluntaristic account of the state supplied by contract theory and the idea of virtue inherited from republican political thought.Footnote1 Following Hobbes, he claims that men come to constitute a civil state and establish a legitimate political body only through a social contract. Against Hobbes, Rousseau maintains that the ties that bind the citizens together cannot rest on prudence alone, but on deeper changes in their personality structure that turn them into moral and social agents. This ‘remarkable change’ entails that ‘the right which each individual has to his own estate is always subordinate to the right which the community has over all: without this, there would be neither stability in the social tie, nor real force in the exercise of Sovereignty’.Footnote2 To avoid clashes between general and particular wills which could be pernicious for the body politic, citizens need to be virtuous—know the requirements of the General Will and be able to conform to it. Patriotism is, for Rousseau, the only means to teach citizens how to be virtuous and thus, exact their compliance with the General Will. Since the love of humanity has a very weak motivational force, and since ‘we voluntary will what is willed by those we love,’Footnote3 Rousseau contends that we need to confine our compassion to those around us with whom we have stable and permanent intercourse: our fellow citizens. From this perspective, a truly cosmopolitan society would not be at all viable, ‘such a society, with all its perfection, would be neither the strongest nor the most lasting: the very fact that it was perfect would rob it of its bond of union; the flaw that would destroy it would lie in its very perfection.’Footnote4 In short, Rousseau views patriotism as a device for fostering collective identities and through this solving the problem of compliance affecting Hobbesian readings of the social contract.Footnote5

An alternative account of patriotism as source of identity and compliance derives from conservative thought. The more traditionalist version comes from the Catholic opponents of the French Revolution: Maistre, Bonald and Chateaubriand. For these authors patriotism entails full identification with locality, monarchy, and religious faith. Its motivational force rests on fear of God and submission to the church's moral teaching.Footnote6 A more philosophically compelling version is proposed by liberal conservatives from Burke to Oakeshott. Their account of loyalty and allegiance to the social and political institutions of the country rests on the evolutionary moral psychology of individuals interacting in small, close-knit groups. As Burke famously put it: ‘To be attached to the subdivision, to love the little platoon we belong to in society, is the first principle (the germ as it were) of public affections. It is the first link in a series by which we proceed toward a love to our country and to mankind.’Footnote7 Here, social conventions arisen as solutions to coordination problems ‘not only reconciles us to any thing we have long enjoy'd, but even gives us an affection for it, and makes us prefer it to other objects.’Footnote8 People's ability to empathize with those who suffer an injustice is then used to explain both group loyalty and political allegiance without the need for a Hobbesian sword. Contra Rousseau's, this alternative account of patriotism rejects the very notion of social contract as a basis for collective identity and reduces questions of legitimacy and compliance to conformity to pre-political values, principles and institutions whose origins are either revealed or immemorial.

These two philosophical perspectives have had a lasting influence on more sociological reflections on patriotism. Classic and modern social theory has highlighted patriotism's power to establish and maintain solidarity within and between the groups composing modern nation-states. Emile Durkheim, for instance, viewed patriotism as a crucial element in the development of ‘organic solidarity.’ For him, patriotic identification would allow people to preserve the internal cohesion and identity of social groups across time, thus, overcoming the anomie brought about by the collapse of traditional social order for which the nation-state bear clear responsibilities.Footnote9 Similarly, Max Weber attributed to patriotic sentiments the ability to integrate the masses within the framework of the nation-state and be ‘a vehicle for, and embodiment of, […] Kultur.’Footnote10 These two lines of thinking are brought together by Ernest Gellner in his attempt to clarify the connections between nationalism and social change by noting that,

nationalism is a phenomenon connected not so much with industrialization or modernization as such, but with its uneven diffusion. The uneven impact of this wave generates a sharp social stratification which, unlike the stratifications of past society, is (a) unhallowed by custom […], (b) is not well protected by various social mechanisms [thus] providing maximum opportunities and incentives for revolution, and which (c) is remediable, and is seen to be remediable, by “national” secession.Footnote11

Communitarians have combined themes developed by these two traditions of thought and put forward an epistemology of the self aimed at questioning liberalism as a coherent and feasible political theory while advancing a sociologically informed re-evaluation of patriotism.Footnote12 Alasdair McIntyre, for examples, notes that ‘from the standpoint of individualism I am what I myself choose to be,’ and points out that such a conception is ‘an illusion and an illusion with painful consequences.’Footnote13 For him, individualism fails to acknowledge that ‘the story of my life is always embedded in the story of those communities from which I derive my identity’ and is thus, responsible for the anomie and moral hollowness of modern life, which has now ‘be assigned the status of an achievement by and a reward for the self.’Footnote14 Similarly, Michael Sandel objects to Rawls’ deontological approach that ‘Only if my identity is never tied to the aims and interests I may have at any moment can I think of myself as a free and independent agent, capable of choice.’Footnote15 However, Sandel believes such a notion of agency is implausible on both epistemic and normative grounds:

To imagine a person incapable of constitutive attachments such as these is not to conceive an ideally free and rational agent, but […] a person wholly without character […] for to have character is to know that I move in a history I neither summon nor command.Footnote16

There are grave problems with this [procedural/cosmopolitan] model of liberalism, which can be properly articulated only when we open up ontological issues of identity and community. There are questions about the viability of a society that would meet these specifications, and issues about the applicability of this formula in societies other than the United States.’Footnote17

Although the Communitarian critique of liberalism can support a variety of contradictory political positions, the authors just mentioned employ it to advance a republican public philosophy promoting people's patriotic identification with the values embodied in actual nation-states.Footnote18 As such, they end supplying philosophical arguments to a flourishing historiography engaged in defending the nation and nationalism from the attacks of modernists, constructivists and globalist.Footnote19

The question I want to raise here is whether this communitarian conception of the self could support the progressive policies and institutions advocated. I shall try to show that their appeal to republican virtues notwithstanding, communitarians in reality end up supporting a conception of the self that comes close to what Viroli calls an ‘ethnic’ (as opposed to a ‘civic’) model of patriotism, which is incapable of engendering them.Footnote20 For Viroli, ‘civic’ models of patriotism stress the role of politics and subjective elements like beliefs and choice, whereas ‘ethnic’ models highlight the role of objective factors like ancestry and mores. This ‘ethnic’ reading of patriotism comes to the fore when the communitarians’ account of identity is fleshed out.

2.1 Embedded selves and plural identities

Communitarians often give the impression to conceive the self as an essentialist and backward-looking entity. This impression is in part due to the fact that their accounts are always proposed as part of a critique of the disembedded liberal self, which leave the substantive side underdeveloped. However, the scattered textual evidence reinforces this impression. Individual identities are described as embedded in national communities and constrained by social practices. Moreover, the features that define and distinguish those communities and practices from others are themselves said to be not a matter of person belief and certainly beyond choice.Footnote21 Lore, national myths and languages seem, therefore, to assume the status of ‘primordial social facts’ that transcend and set constraints on the ability of individuals and groups to determine themselves. Tellingly, communitarians suggest picturing identity as a system of concentric circles that enclose and constrain the individual as agency. As MacIntyre puts it,

I am brother, cousin and grandson, member of this household, that village, this tribe. These are not characteristics that belong to human beings accidentally, to be stripped away in order to discover ‘the real me’. They are part of my substance, defining partially at least and sometimes wholly my obligations and my duty. Individuals inherit a particular space within an interlocking set of social relationships; lacking that space they are nobody, or at best a stranger or an outcast.Footnote22

We cannot regard ourselves as independent in this way without great cost to those loyalties and convictions whose moral force consists partly in the fact that living by them is inseparable from understanding ourselves as the particular persons we are-as members of this family or community or nation or people, as bearers of this history, as sons and daughters of that revolution, as citizens of this republic.Footnote23

By contrast, civic conceptions emphasize the pluralistic and artificial nature of the modes of identification that bind people together into communities and nations. While sharing with the communitarians the idea that identity is a dialogical, inter-subjective, and historical phenomenon, civic conceptions also focus on identity's intra-subjective dimension and the complex web of relations created by the inter and intra-subjective dialectic.Footnote26 From this perspective, lore, mores, languages and histories do not express any essential feature, nor do they amount to primordial social facts that set limits on the community's ability to determine itself, or to ‘attachments they discover.’Footnote27 Rather, they are the repositories within which identities are re-constructed from one generation to the other in an ongoing collective struggle to tackle new challenges. Thus, civic conceptions view identity-building as a dynamic and forward-looking process which leaves to individuals and groups significant powers of self-determination.Footnote28 Following Georg Simmel's metaphor of social circles,Footnote29 this civic conception of identity can be aptly described as a system of intersecting circles which define the individual as the locus of multiple belonging and sources of identification. Two important implications follow from this Simmelian conception of identity. First, it attributes to the individual room for singularity and agency without, at the same time, disembedding it. Second, it perceives the coordination of social circles the individual belongs to, and of the groups that compose the social, as the domain of politics, conceived as both a genuine normative activity and a set of administrative institutions. In short, civic conceptions emphasize the dynamics of identification, rather than the social determinants of identity.Footnote30 For them, patriotism is a political virtue founded on feelings of allegiance to one's own political community, while the latter is seen as a self-determining pluralistic entity which, in a Rousseauian spirit, acknowledges its members as autonomous agents.Footnote31

Communitarians seem to view this ideal of patriotism, and the conception of political community it embodies, as too close to cosmopolitan liberalism to generate the kind of identification needed to counterbalance modern anomic tendencies. Thus, they would likely extend to it the charges moved against liberal theories, of being ‘not morally self-sufficient but parasitic on a notion of community it officially rejects […] that it must draw on a sense of community it cannot supply and may even undermine.’Footnote32 In my opinion, this criticism rests on a mystical, all-encompassing notion of community and, thus, on a questionable epistemology of the self.Footnote33 First, at the empirical level, the concentric model of identity underpinning it fails to appreciate the deeply pluralist nature of modern life and the role this pluralism plays in creating complex social identities. Community is always, or primarily, presented as a singular entity rather than in plural terms. Likewise the nation is often conceived as a community writ large.Footnote34 This glosses over the existence of an internal pluralism and leaves unexplored the complex relationships between the inter and intra-subjective dimensions of identity. As a result, it not only plays down the possibility of mixed and plural identities, but also views multiple and overlapping loyalties suspiciously. It also fails to account for the way in which identity can change over time or undergo deep revisions. Phenomenologically it is, however, the very existence of plural attachments to multiple communities that explains people's ability to redefine their identities (and the sudden and rapid way in which this can occur) in situations of social breakdown and civil war.Footnote35

Communitarians often give the impression of being fully aware of these shortcomings. However, they contend that since only an ‘ethnic’ type of patriotism is compatible with an ontologically valid model of identity, any alternative would actually end promoting atomization and higher levels of anomie. As Taylor puts it:

Of course patriotism is also responsible for a lot of evil, today as at any time. […] But whatever menace the malign effects have spawned, the benign effects have been essential to the maintenance of liberal democracy. […] Not only has patriotism been an important bulwark of freedom in the past, but it will remain unsubstitutably so for the future.Footnote36

the political survival of any polity in which liberal morality had secured large-scale allegiance would depend upon there being enough young men and women who rejected that liberal morality. And in this sense liberal morality tends toward the dissolution of social bonds.Footnote37

3 Mapping patriotism

As well known, the word patriotism derives from the Latin word pater, meaning father and indicating sentiments of love and loyalty toward the family. From this root evolved the term patriots, to refer to fellow countrymen, and the word patria, to indicate the native country. This etymology highlights some interesting antinomies. One of this is referred to by A.D. Smith in his discussion of David's Oath of the Horatii, a dramatic icon of patriotism. In the painting, the Horatii brothers swore on their father's sword to represent their patria (Rome) and fight the Curiatii brothers, representing the enemy city of Albi; even though one of the sisters of the Curiatii, Sabina, is married to one of the Horatii and one of the sisters of the Horatii, Camilla, is betrothed to one of the Curiatii.Footnote38 As Smith notes, ‘the most fundamental sentiments evoked by nationalism were, paradoxically, those of family paradoxically because real families can constitute an obstacle to the ideal of a homogeneous nation.’Footnote39 Modern nationalism brought to the fore a further antinomy, that between locality and the nation-state. The individual's identification with his pays is to a large extent incompatible with his duties toward the patrie, to the point that accomplishing the latter often requires the destruction of the former as a locus of identification and self-government. The ruthlessness with which nationalism affirmed the priority of the nation above other values and attachments has encouraged the perception of patriotism as a blind force supporting ethnocentric, racist and fascist ideologies. Attempting to rescue patriotism from this negative characterization, a number of binary distinctions have been elaborated. Besides the civic/ethnic divide mention above, there has been a parallel attempt to distinguish between nationalism and patriotism.Footnote40 Thus, Doob maintains that, ‘there is no reason to suppose that the personality traits associated with love of country are the same as those connected with hostility toward foreign countries or foreigners.’Footnote41 Kosterman and Feshbach further clarify that

Patriotism taps the affective component of one's feelings toward one's country, […]. It assesses the degree of love for and pride in one's nation—in essence, the degree of attachment to the nation. The Nationalism vector, in comparison, reflects a perception of national superiority and an orientation toward national dominance.’Footnote42

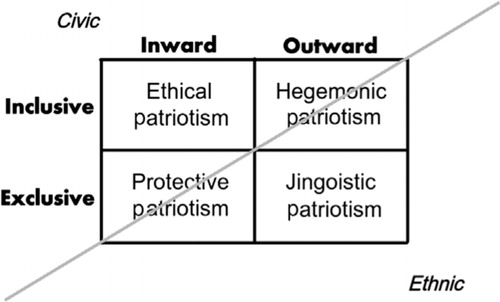

The 2×2 matrix given in presents a taxonomy of patriotic forms of identification generated by criss-crossing two distinct aspects of the process of identification. The first concerns the perspective from which identity can be viewed. Identity can be represented as a dynamic and interactive process resting on an ongoing, self-reflexive examination of the values and beliefs shared by a group. On this reading, social cohesion depends on the power of public institutions to create and sustain networks of solidarity between the groups and subgroups composing the body politic. Alternatively, Identity can be seen from a relational perspective which focuses on comparison with the out-group occupying adjacent social spaces or alternative polities. In this case, social cohesion is the outcome of competitive pressures operating between groups, for it is the relative position occupied by a given group that define the way in which its members see and perceive themselves. For the self-reflexive perspective, collective identity rests on the ‘inward-looking’ attitude of its members and their regimes, whereas from the relational perspective it rests instead on its ‘outward-looking’ mind-set. The second aspect pertains to the overall objectives collective identification is called to achieve. Collective identity can aim at (1) establishing ties between people and groups previously un- (or only partially) related, or (2) transforming hierarchical relations of domination into more horizontal relations of cooperation. Nation-building and democratization processes that took place in Western Europe in the 20th century represent an example of this type of collective identification.Footnote48 Alternatively, collective identity could represent a dynamic process the goal of which is to (1) reinforce social boundaries, or (2) establish a ranking order between groups and classes. The 19th century creation of absolute sovereign states with centralized administrations and free-market economies epitomizes this alternative route.Footnote49 In the first case, to establish a collective identity entails a struggle for inclusion, while in the second case it is a means for exclusion. Criss-crossing these variables yields the four ideal-types reported below. The diagonal gray line highlights the fact that two of this ideal-types cut across the civic/ethnic divide.

Exclusionary types of patriotism come in two forms.Footnote50 The first, which I label ‘Protective Patriotism,’ is a form of patriotism committed to preserving the ethnic cohesion or cultural authenticity of the patria from external influences. Protective patriotism arises because of a concern about the lowering of the boundaries that separate ‘us’ from ‘them,’ where ‘them’ stands for either those living in neighboring areas or the migrants who settle within the social space occupied by the in-group. These sentiments of rejection of the other are fed by worries about the loss of identity due to ethnic and cultural creolization. Recent political phenomena like Italy's Northern League, Austria's Freedom Party, France's National Front and the British National Party, to mention only a few European cases, epitomize this type of patriotism and related concerns.Footnote51 More than a coherent racist ideology, what motivates Protective Patriotic movements are two worries: (1) a deep egotistical fear of losing the social and economic benefits in-group members enjoy and (2) heightened feelings of powerlessness in the face of unwanted social changes, as clearly expressed in their anti-establishment language and politics. A plain and coherent racist outlook characterizes instead the second type of exclusionary patriotism, ‘Jingoistic Patriotism.’Footnote52 Two features distinguish this type of patriotism from the previous one. First, a belief in the superior or exceptional nature of ‘our’ patria compared to all others. Accordingly, ethnic, religious, cultural, or even political cleavages are seized upon to distinguish ‘us’ from ‘them’ and establish some ranking order where ‘we’ seat at the top. Second, the idea that only by engaging in struggles for domination can the special identity of the group be affirmed. Ideas like ‘mission’ and ‘destiny’ pervade its patriotic language and help mobilize both the symbolic and material resources needed for projecting the power of the group outside.Footnote53 Unlike its inward-looking counterpart, Jingoistic Patriotism exalts martial virtues, promotes social change and supports pro-establishment policies. It is also consumed by concerns about internal enemies (agitators, Jews, terrorists, etc.) to a degree unmatched by the Protective type. Their historical importance notwithstanding, we can rightly turn against them the criticisms Gellner improperly moves against all forms of nationalism: first, that ‘their precise doctrines are hardly worth analysing,’ and second, that both suffer ‘from pervasive false consciousness.’Footnote54

Inclusive models of patriotism are similarly of two types. The first, ‘Hegemonic Patriotism,’ combines a concern for internal inclusion with a hostile attitude toward outsiders. While patriotic identification rests on the Schmittian friend–enemy distinction, in-group inclusion is seen as the necessary pre-condition for competing successfully against the out-group. Although Hegemonic Patriotism grounds identity on a distinction between ‘us’ and ‘them’ similar to that employed by exclusionary types, the content upon which this distinction rests sets it apart from them. In fact, very often such distinction has no clear or substantive content at all. This is the case for Carl Schmitt's, for whom, ‘Every religious, economic, ethical, or other antithesis transforms into a political one if it is sufficiently strong to group human beings effectively according to friend and enemy.’Footnote55 More substantive definitions of ‘us’ elect cultural rather than ethnic traits as the defining element of identity. In the words of its most articulate exponent, Max Weber, ‘The significance of the “nation” is usually anchored in the superiority, or at least in the irreplaceability, of the cultural values that are to be preserved and developed only through the cultivation of the peculiarity of the group.’Footnote56 However, the ‘cultural values that are to be preserved and developed’ are conceived neither as primitive historical facts, nor as widely shared. That is why Weber and those who endorse Hegemonic Patriotism insist on policies of cultural assimilation and political inclusion as the precondition for group fitness in a highly competitive international setting. Epistemically, Hegemonic Patriotism is more concerned with the definition of ‘them’ than is with ‘us’ as the main determinant for identification and compliance. Politically, it perceives democracy instrumentally as a means to empower national elites while shielding them from the masses.

The second inclusive type of patriotism, ‘Ethical Patriotism,’ shifts the focus back from ‘them’ to ‘us.’ The development of a shared identity capable of generating allegiance and compliance is here demanded of political arrangements which can assure both the moral integration and the political inclusion of all members. Ethical Patriotism views ‘us’ as a complex and variegated entity, the outcome of political and historical accidents. The dynamics of the self upon which it rests is the one invoked by Emile Durkheim, for whom, ‘as long as there are States, so there will be national pride, and nothing can be more warranted. But societies can have their pride, not in being the greatest of the wealthiest, but in being the most just, the best organized and in possessing the best moral constitution.’Footnote57 For it, the nobility or authenticity of a nation is never a matter of birthright, nor can it be established out of Darwinian struggles for survival and hegemony. Rather, it is a moral achievement: the outcome of an inward-looking ethical activity the aim of which is to supply collective representations that can help renew the source of social solidarity. Accordingly, it advocates the adoption of values and practices that can pursue unity without imposing uniformity, guarantee justice while preserving plurality and yield the benefits of competition without undermining the possibility of cooperation with minorities, neighbors and strangers. In marked contrast to the elitism of its Hegemonic counterpart, Ethical Patriotism attributes an overriding value to the ability of social rites to foster collective identities. Hence, the advocacy of participatory forms of democratic engagement, the (re-)establishment of intermediary bodies that could fill the gap between the individual and the state and the integration of territorial criteria of representation with new functional forms.Footnote58

3.1 Which patriotism? Whose identity?

The taxonomy I have just proposed is meant to challenge the communitarians’ belief in essentialist notions of identity while highlighting their failure to distinguish between alternative types of patriotic identification. Its scope is twofold. First, it is meant to help rationalize (in a Weberian style) the process which brought about modern collective identities, nation-states, and nationalist ideologies. This process generated (and was in turn generated by) a number of patriotic movements whose actions, conceptions of the self, and political objectives are embodied by the four ideal-types presented above. In other words, these ideal-types describe alternative historical ways in which national communities were imagined, criteria of membership redefined, solidarity expanded and the institutions of the nation-state established. Even more interesting, from my perspective, is the fact that this plurality of patriotic forms does not coincide with single national experiences as claimed by Khon,Footnote59 and cannot be thought of as related to distinct national characters. Indeed, the history of all European nation-states is characterized by the struggle and succession between inclusive and exclusive, inward and outward-looking types of patriotism.Footnote60 Second, the proposed taxonomy is meant to map the analytical space available for the normative analysis of diverse types of patriotism and the worldviews they support. Acknowledging patriotism as a crucial source of identity and a force for compliance means (1) recognizing its inherent pluralistic nature, (2) engaging in the evaluation of the relative desirability of each ideal-type, and (3) defining the institutional milieu that could help engender the most desirable type. It is to this normative task I shall turn now.

To begin with, I maintain that all the ideal-types listed above have the ability to promote identification and foster some form of compliance. In other words, they can all pass the feasibility test required by Taylor.Footnote61 This is also the case for Ethical Patriotism, which is the type I wish to endorse. Unlike cosmopolitan approaches, Ethical Patriotism recognizes both the individual's need for group identification and the emotive basis of compliance. For it, individual identities are the outcome of dialogical processes taking place at local level and involving the groups the individual is embedded in. Identity is thus, the result of a process of identification with fellow-members based on shared (1) sets of values, (2) collective representations, and (3) civic rituals. Moreover, it views individual compliance not as the result of a mere rational evaluation, but as dependent on shared norms and practices which are constitutive of the self. Even when it adopts an individualist stance or the language of rights, Ethical Patriotism does so not because it believes in historical and universal categories, but because it views the individual and the language of rights as part of the values shared by the group. As Durkheim eloquently puts it,

the individualist who defends the rights of the individual defends at the same time the vital interests of society, for he prevents the criminal impoverishment of that last reserve of collective ideas and feelings which is the very souls of the nation.Footnote62

However, the conceptions of identity, compliance and community entailed by Ethical Patriotism differ from those advanced by communitarians as well. Ethical Patriotism views internal pluralism as both a fact and a value. This outlook is especially compelling when facing patriotic ideal types, like the Hegemonic and Jingoistic, that view the nation-state as some sort of community writ large. Ethical Patriotism acknowledges the arbitrary and contingent nature of actual national boundaries and advances a principled rejection of both the politics of homogenization pursued by the nation-state and the logic of domination endorsed by empire. First, it maintains that since modern nation-states are never homogeneous entities, the cultural unity sought by Hegemonic and Jingoistic patriots would require policies of internal colonization that could engineer it. The outcome would therefore, be a stark trade-off between the nation's claim to unity and the claim for self-determination of minorities and local communities, and the likely eradication of the very institutions the communitarians themselves acknowledge as bulwark against atomism and anomie: local particularities, cultural traditions, and ways of life. Second and consequently, Ethical Patriotism perceives Hegemonic and Jingoistic patriotic project that aims at in-group homogeneity and out-group domination as structurally unable to promote inter-group identification or preserve the allegiance of those whose identity rests on multiple affiliations. This is chiefly evident in relation to minorities that do not fit in with the criteria devised to distinguish ‘us’ from ‘them.’ Where these minorities form territorial enclaves, attempts to create homogenous national identities would inevitably generate secessionist and irredentist movements that could eventually challenge the unity of the body politic. Not less problematic is the dynamic of exclusion Hegemonic and Jingoistic modes of patriotism sanction against other more diffuse minorities whose identity rests on mixed affiliations and ties, namely migrant and Diaspora groups. Hegemonic and Jingoistic types of patriotism view these minorities as always suspect and in need of being restrained by discriminatory measures that deny, suspend or revoke their membership, thus, turning them into metics or even enemies.

A third class negatively affected by Hegemonic and Jingoistic ideal-types is that composed of people whose identity (or parts of it) is denied by the very values the latter exalt. Martial virtues, Darwinian notions of fitness and ideals of ethnic and cultural purity cannot be the basis upon which disabled, women, homosexuals, and those with mixed identities can base their self-understanding. Any call of duty based on able-bodied rhetoric, masculine iconography, etc. is likely to cause defective or unsustainable processes of identification on the part of these groups. Similar considerations can finally be developed concerning the ability of Hegemonic and Jingoistic patriotisms to assure the compliance of those individuals belonging to the in-group, but whose interests are systematically sacrificed for ‘love of country.’ Interests and rational calculation enter the frame reinforcing doubts about the desirability of these ideal-types. Walby notes for instance that,

Even the most cohesive ethnic national group almost always entails a system of social inequality, and one where the dominant group(s) typically exercise(s) hegemonic control over the ‘culture’ and political project of the ‘collectivity’. […] Ethnic/national conflicts, then may be expected to benefit the interests of the members of that grouping differentially. Different genders (and classes) may, therefore, be differentially enthusiastic about ‘the’ ostensible ethnic/national project, depending upon the extent to which they agree with the priorities of ‘their’ political leaders.Footnote66

The conclusion I draw from this discussion is that while Protective Patriotism is a purely reactive form, Hegemonic and Jingoistic ideal-types are incapable of retaining the allegiance of those constituencies they discriminate against and are therefore, prone to periodic crisis of legitimacy and internal conflict. This means that, as ideal-types, Hegemonic and Jingoistic modes of patriotism tend to promote institutions and selves that are incompatible with the ideals of self-determination they profess. It is this inner contradiction that hinders their ability to promote wide-spread forms of identification, retain people's allegiance and assure compliance. By contrast, Ethical Patriotism views multiple affiliations as intimately connected to people's identity and, therefore, in need of safeguard. Moreover, it regards those embodying multiple and mixed identities as potential nodes upon which to build transcultural political networks and identities. Thus, it perceives migrant and Diaspora communities neither as a danger to national identity requiring separation, nor as a social problem calling for assimilation.

4 Farewell to TINA: patriotism, value, and milieu

Historically, Ethical Patriotism and the collective movements endorsing it are part of a somewhat neglected European political tradition—mutualism. The contribution of this political tradition to nation-building in the 19th century, by expanding local forms of solidarity and mutual recognition to national levels, and to post-war reconstruction e democratization in the 12th century has been crucial, although it has not always been properly recognized. Sadly, even in these instances mutualist forces failed to resist the power of political elites welded to more aggressive patriotic visions seeking internal homogeneity and external domination. Hence, the tendency to view Ethical Patriotism as an unfeasible ideal. From my perspective, this failure is due more to the type of power dynamics promoted by the nation-state than to some allegedly epistemic weaknesses affecting it. The explication of this dynamic gives me the opportunity to clarify what institutional milieu is required to strengthen it vis-à-vis its less desirable alternatives. This endeavor is particularly, important when set against current attempts to build a European-wide common identity capable of supporting the political institutions of the Union as a bulwark against the threats posed by globalization and a resurgent protective opposition to it. In this section I focus on two features of this milieu: the political conception that should drive the EU as a post-national polity and the model of citizenship it ought to adopt and engender.

4.1 The patria in a globalizing world

The modern state's endless quest for administrative efficiency and military effectiveness has caused the functional differentiation of activities and roles, and the political centralization of decision-making and law enforcement. This is the process Polanyi refers to as the ‘great transformation.’Footnote68 First, it undermined the social and political relevance of local communities and intermediary bodies. Second, it trigged the fragmentation and dislocation of local communities. The combined effect was mass migration and the rise of widespread Protective patriotic movements noted by Hobsbawm.Footnote69 Given the unresponsive nature of 19th century liberal states, those movements proved unable to affect decision-making and challenge the agenda of the regimes supporting those changes. Alas, social discontent was exploited by elites supporting colonial adventures, or nationalist projects having ethnic agenda and hegemonic aspirations. Hence, the increasing antagonistic power politics that eventually led to World War I and II. It is this internal dynamic that accounts for the relative marginal role played by Ethical Patriotism vis-à-vis competing patriotic ideal-types and the troublesome history of modern nationalism. However, Ethical Patriotic ideals and movements made it possible to build the more inclusive welfare states needed for post-war reconstruction. A similar dynamic is currently at work under the aegis of globalization. While state sponsored free-market policies have promoted large-scale enclosures that undermine the viability of local and national communities, centrally imposed structural reforms have ‘pushed marketization and privatization forward […] narrowing the frontiers of the public domain in the process.’Footnote70 As for the Speenhamland system discussed by Polanyi, these changes are responsible for the mass migration toward the rich parishes of the West and the rise of a new wave of protective patriotic movements easily exploitable by undemocratic nationalistic elites.

Cosmopolitans like Habermas believe the challenges posed by globalization can be countered by supranational bodies that can replicate the process of vertical integration followed by the nation-state within its borders. Supranational entities like the EU are thus, seen as bulwarks against both the hegemonic aspirations of markets and the imperial pretensions of the sole remaining superpower. The analysis developed above casts serious doubts on this solution. First, the cosmopolitan project overrates the success of the nation-state in fostering stable collective identities and democratic control. Second, it rests on a Panglossian faith in the ability of supranational agencies and universal values to promote patriotic identification and democratic governance. The nation-state has been not only a very poor substitute for the loss of community brought about by modernization, but clearly the main instigator for the atomization of social relations.Footnote71 Likewise, universalistic principles and liberal-democratic practices have, pace Habermas, repeatedly shown themselves to be not only a very weak base upon which to ground collective identities, but also a possible source of anomie. Thus, far from redressing the weaknesses affecting national and global governance, the creation of supranational political entities which endeavor to supersede the nation-state by adopting its forms and practices could have serious deleterious side-effects. For one thing, they will increase the distance between citizens and representative institutions further, weakening patriotic identification, individual compliance and democratic accountability in the process. The 2005 defeat of the European constitutional project is an indication of the problems cosmopolitan solutions face. Rather than creating a framework for a Union of self-governing regions and communities held together by shared universal values, the constitutional project has come to be seen as another step toward ‘modernanglization’—i.e. a sleight of hand with which unaccountable elites try to legitimate themselves while pushing forward a neoliberal agenda by using TINA as their own rallying cry.Footnote72

In my view, globalization calls neither for a defense of the nation-state per se, nor for the extension of its template to regional and global levels. Rather, it demands a re-evaluation of the type of polity that has pushed globalization forward and used it as a means for reducing democratic spaces and accountability. To flourish, Ethical Patriotism requires an institutional milieu capable of resisting the logic of TINA, and where forms of subsidiarity, functional representation and local participation combine to produce a more democratic and decentralized system of governance. Engendering more democratic political institutions based on the principles of devolution and subsidiarity would, in my opinion, have three positive effects. First, it would encourage local identities, civic virtues and networks of trust, thus, strengthening social solidarity. Second, it would reduce the problems related to the information flow between the center and the periphery, thus, decreasing the risks of coordination failure and the costs of law enforcement. Finally, it would highlight the links between policy commitment and expenditure, thus, improving the responsiveness and accountability of those involved in the political process. A democratic system of this type would not generate the large-scale Protective patriotic movements discussed above and would, therefore, be able to resist the maneuvering of political elites with ethnic agenda and hegemonic aspirations. Indeed, a great deal of the current disenchantment with the European constitutional project can be accounted for by the growing chasm between the Union's rhetorical acceptance of subsidiarity and multilevel governance as constitutive principles and the pursuit of policies that in reality mortify them. Far from fostering the autonomy of regions and communities, the Union aims to enable them to compete in global markets through the commodification of their natural and human resources.

4.2 From rights to rites: the citizen as a patriot

Similar considerations can be expressed concerning the model of citizenship to adopt and engender. Historically, the notion of citizenship has evolved from a purely political concept stressing belonging and active engagement to a semi-juridical category outlining the rights and freedoms the citizen is entitled to.Footnote73 Citizenship as sets of rights is meant to advance a more modern understanding of the relationship between the value of individual autonomy and the principle of self-determination. As Constant wrote, ‘individual independence is the first need of the moderns: consequently one must never require from them any sacrifices to establish political liberty.’Footnote74 Liberal thought regards political rights as a by-product of civil rights. Since individual autonomy represents the sphere where the individual is free to do what he wants, it is identified with pre-political rights that set strict limits to what a legitimate polity can do. This means that the definition of individual entitlements is independent from politics and that the task of political institutions is to maximize the sphere of autonomy to which each individual is entitled to. Hence, liberals view constitutions as external to the political process and resting on philosophical tenets rather than actual consent.Footnote75 The implication for the principle of self-determination is unambiguous. A community of autonomous individuals requires universal formal procedures that can combine individual entitlements to maximize the total sum of liberties enjoyed by all. Democratic politics becomes, therefore, a means for ‘aggregating’ pre-political entitlements, while universal rights turns out to be its paramount source of legitimacy. To this end, what is needed is legitimate and responsible leadership, rather than the active participation of the demos to policy-making. This distinctly liberal ideal of citizenship is at the root of current cosmopolitan attempts to close the gap between citizenship rights and human rights and build post-national identities whose allegiance goes to a constitution embodying legitimate universal values.Footnote76 Politically, it is responsible for the various institutional reforms that in the last thirty years have undermined the authority of national parliaments to favor the insulated administrative bodies composing the regulatory state.Footnote77

In the second post-war period, progressive liberals attempted to merge this notion of citizenship as rights with the principles underpinning the welfare state, thus, advancing an ‘expansive’ model of citizenship connecting civil liberties with political and social rights.Footnote78 This attempt incited strong objections, coming chiefly from inside the liberal camp itself. Neoliberals viewed this model of citizenship as resting on an ideal of social justice that was theoretically unsound and politically unfeasible: (1) it found inspiration in an incoherent notion of positive liberty as self-mastery that justified pervasive state interference; (2) it advocated a patterned conception of distributive justice that promoted the exploitation of the well-off members of the polity and depleted its entrepreneurial spirit.Footnote79 In the 1980s, the disintegration of the coalition supporting the welfare consensus brought about the demise of this model of citizenship and ushered in a neoliberal conception that played down economic and social rights while stressing individual duties. According to this new conception of citizenship, a liberal polity must be committed to principles enabling its citizens to compete in a global market economy while guaranteeing a safety-net for those who fail to do so successfully.Footnote80 The disputes that accompanied the inception of the ‘workfare’ state highlighted two things. First that ‘the debate between libertarian and social democrats are not within a political framework of rights, they are about that framework.’Footnote81 Second, that ‘the protective conception of citizenship is a very unlikely candidate for creating the overlapping consensus of reasonable doctrines required by Rawls for the stability of a modern, pluralist polity.’Footnote82 Indeed, this neoliberal conception of citizenship has augmented internal conflicts and undermined the legitimacy of the liberal regimes adopting it further. Across Europe, its imposition has been the catalyst for mobilizing the populist movements mentioned above, whose aim is that of re-fashioning the liberal polity along ethnic lines to compensate for the loss of national status and the creolization of indigenous societies.

To neutralize the negative politics of populist movements with ethnic agenda and hegemonic aspirations, what is needed, in my opinion, is a new conception of citizenship which can accommodate both universal values and active involvement: rights and rites. This calls first of all for a rebalancing of representative and participative forms of democratic politics, with the former operating mostly at national and transnational levels and the latter taking place at local and regional levels. Past attempts to impose a purely representative model of democracy across all territorial levels have simply revealed themselves to be mere elitist practices devised to hollow out democratic politics and turn citizens into passive subjects. The same can be said concerning the parallel attempts to reduce the relevance of local government by imposing a centralized state-form structured as a hierarchical system of nested authorities. In addition to this rebalancing, there also arises the need to rethink the forms of democratic representation operating at national and transnational levels. Since social and geographical mobility have reduced the relevance of the territorial dimension as the locus of identity, territorial forms of representation need to be integrated by functional modes of representation.Footnote83 Moreover, given that subsidiarity and the devolution of authority at sub and supra-national levels will yield a number of distinct demoi rather than as a single, homogeneous demos, multilevel governance calls for the development of a new, pluralist conception of citizenship structured as a network form of organization. Finally, even at national and transnational level there is the need to combine traditional forms of representation with deliberative instruments which can be activated directly by the citizens as feasible alternatives to referenda.Footnote84 In short, the political milieu most conducive to Ethical Patriotism is a democratic system where deliberative institutions and a multilevel system of governance seek to constitute the subject as a participant in political processes (at a variety of levels) and as an active member of multifarious communities and associations.

5 Conclusion

The 2005 defeat of the European constitutional project is symptomatic of the growing problems facing cosmopolitans who, like Habermas, think it possible to build national and transnational identities within a universalist framework. These attempts systematically underestimate the conditions needed for engendering patriotic identification and the disruptions caused by the social changes necessary to bring them about. I have argued that patriotic movements and ideologies are able to undermine cosmopolitan aspirations because of their ability to appeal to, and build upon, in-group modes of identification capable of fostering loyalty and allegiance. The rising of these patriotic movements and ideologies is often due to the relational void caused by disruptive social changes imposed by central governments pursuing cosmopolitan agenda and people's need to react against those changes to preserve their identities. This explains the relation between nationalism and modernization and its reappearance in post-modern times under the pressure of globalization. In both cases, the rise of wide-spread nationalist patriotic movements is connected to the mass migration flows caused by centrally imposed structural changes designed to expand markets while freeing them up from social control. By pursuing a constitutional settlement that elects abstract rights as its main values while promoting unpopular free-market policies, the European constitutional project is, in effect, following earlier cosmopolitan agenda and facing the very problems they experienced before. I maintain that to avoid a repeat of the devastating defeat cosmopolitans suffered on the eve of the First World War, we need to reconsider the ability of abstract and universal values to foster collective identities and promote feeling of loyalty and allegiance toward one's own political community.

Acknowledgements

This article originates as a conference paper delivered at the GARNET-JERP 5.2.1 final conference ‘The Europeans. The European Union in Search of Political Identity and Legitimacy,’ Florence, 25 and 26 May 2007. I would like to thank the discussant, Klaus Eder and the conference organizer, Furio Cerutti, for their critical observations. I am also grateful to three anonymous reviewers and the journal's editorial team for helping me identify several conceptual obscurities. A special thank goes to Alan Scott for his continuous encouragement and support throughout. Any error rests of course with the author.

Notes

1. Jean Jacques Rousseau's remarks on patriotism are mostly confined to the Discourse on Political Economy (1755), the dedicatory letter of A Discourse on Inequality (1754) and the Considerations on the Government of Poland (1772). French originals now in, The Political Writings of Jean Jacques Rousseau, ed. C.E. Vaughaned (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1915).

2. Jean Jacques Rousseau, ‘The Social Contract or Principles of Political Right’, in The Social Contract and the Discourses, by J.H. Brumfitt and J.C. Hall, ed. and trans. G.D.H. Cole (London: Everyman's Library, 1993), 198.

3. Jean Jacques Rousseau, ‘Discourse on Political Economy’, in The Social Contract, 142.

4. Jean Jacques Rousseau, ‘The Social Contract’, 301.

5. For a restatement of Hobbes’ compliance problem in game theoretical terms, see David Gauthier, Morals by Agreement (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986); Jean Hampton, Hobbes and the Social Contract Tradition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986); and Gregory Kavka, Hobbesian Moral and Political Theory (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1986).

6. As Anthony Smith explains, for the counter-revolutionaries,

The key to society was authority and the root of social authority was religion. Take away religion, and you remove the one sure foundation of social order and individual happiness. Only religion could ensure community between heterogeneous men and women; only full assent to its supernaturally-backed values and norms could give everyone the sense of belonging, of solidarity, which was man's basic need. Anthony Smith, ‘Nationalism and Classical Social Theory’, British Journal of Sociology 34, no. 1 (1983): 28.

7. Edmund Burke, Reflections on the Revolution in France (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), 46–7.

8. David Hume, A Treatise of Human Nature (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1978), 499–500. For the game theoretical reading of Hume's account of conventions, see Allan Gibbard, Wise Choices, Apt Feelings (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990) and David Lewis, Convention (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1969).

9. Emile Durkheim's reflections on patriotism are to be found in his war time writings, Germany above All: German Mentality and the War (Paris: Librairie Armand Colin, 1915) and the posthumous Professional Ethics and Civic Morals (London: Brookfield, 1957).

10. David Beetham, Max Weber and the Theory of Modern Politics (Cambridge: Polity, 1985), 127. For Max Weber's remarks on patriotism, see From Max Weber. Essays in Sociology, ed. H. Gerth and C.W. Mills (London: Routledge, 1948), 77–128, 171–79 and Weber: Political Writings, ed. P. Lassman and R. Speirs (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 1–28, 309–69.

11. Ernest Gellner, ‘Nationalism and Modernization’, in Nationalism, ed. J. Hutchinson and A.W. Smith (Oxford: OUP, 1994), 61, Nations and Nationalism (Oxford: Blackwell, 1983). See also, the complementary work of Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities (London: Verso, 1991).

12. Cf. Alasdair MacIntyre, Whose Justice? Which Rationality? (London: Duckworth, 1988), After Virtue (London: Duckworth, 1985), ‘Is Patriotism a Virtue?’ in Debates in Contemporary Political Philosophy: An Anthology, ed. D. Matravers and J. Pike (London: Routledge, 2003), 286–300; Michael Sandel, Liberalism and the Limits of Justice, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), ‘The Procedural Republic and the Unencumbered Self’, Political Theory 12, no. 1 (1984): 81–96, Democracy's Discontent (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995), ‘America's Search for a New Public Philosophy’, Atlantic Monthly 277, no. 3 (1996): 57–74; Charles Taylor, Sources of the Self (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), Philosophical Arguments (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995—in particular: ‘Cross-Purposes: The Liberal-Communitarian Debate’, 181–203 and ‘The Politics of Recognition’, 225–56), ‘Atomism’, in Philosophy and the Human Sciences (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), 187–210; Reconciling the Solitudes: Essays on Canadian Federalism and Nationalism (Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1993); Michael Walzer, Obligations: Essays on Disobedience, War, and Citizenship (New York: Clarion Book, 1970), Spheres of Justice (Oxford: Blackwell, 1983), ‘Nation and Universe’, The Tanner Lectures on Human Values (Brasenose College, Oxford University, May 1 and 8 1989), ‘Citizenship’, in Political Innovation and Conceptual Change, ed. T. Ball, J. Farr and R.L. Hanson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 211–19, ‘Response to Veit Bader’, Political Theory 23, no. 2 (1995): 247–49.

13. Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue, 220, 221.

14. Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue, 221; Whose Justice, 68.

15. Michael Sandel, ‘The Procedural Republic’, 86.

16. Michael Sandel, The Procedural Republic, 90.

17. Charles Taylor, Philosophical Arguments, 187.

18. Michael Sandel clearly acknowledges the diverse political implications derivable from the communitarian critique of liberalism:

On some issues the two theories [liberalism and communitarianism] may produce different argument for similar policies. […] On other issues, the two ethics might lead to different policies. Communitarians would be more likely to ban pornographic bookstores, on the grounds that pornography offends its way of life and the values that sustain it. But a politics of civic virtue does not always part company with liberalism in favor of conservative policies. Michael Sandel, ‘Morality and the Liberal Ideal’, The New Republic May 7(1984): 17.

The indeterminacy of Michael Sandel's republicanism is discussed by Pettit, ‘Reworking Sandel's Republicanism’, Journal of Philosophy 95 (1998): 73–96. I argue that to avoid supporting conservative values and policies, communitarians like Michael Sandel needs to spell out what type of patriotic identification is compatible with the progressive public philosophy he advocates. The taxonomy I propose here represents a contribution to this clarification.As for the communitarians’ support for the nation-state, quoting approvingly Nisbet, Friedman stresses ‘the communitarians’ surprising indifference to ‘the groups, associations, and localities in which we actually spend our lives’. Generally speaking, the communities with which communitarians are concerned are not families, friendships, neighborhoods, or even other arenas of close human association, but nation-states, Friedman, ‘The Politics of Communitarianism’, Critical Review 8, no. 2 (1994): 298. Admittedly, on this point the textual evidence is more ambiguous. In the conclusion to Democracy's and ‘America's Search’, where he explicitly refers to the nation-state, Sandel recognizes the drawbacks the nationalization of American politics occurred in the early decades of the 20th century had on self-government. However, he seems to view positively the fact that ‘the primary form of political community had to be recast on a national scale’, for ‘Only a strong sense of national community could morally and politically underwrite the extended involvements of a modern industrial order’ Democracy's, 340. See also note 33.

19. One of the main exponents of this historiography is A.D. Smith, whose conception of national identity is strikingly communitarian: ‘Nationalism signifies the awakening of the nation and its members to its collective “self,” so that it, and they, obey only the “inner voice” of the purified community. Authentic experience and authentic community are therefore, preconditions of full autonomy, just as only autonomy can allow the nation and its members to realize themselves in an authentic manner’, National Identity (London: Penguin, 1991), 77.

20. Viroli, For Love of Country (Oxford: Clarendon, 1995), Repubblicanesimo (Roma: Laterza, 1999 exp. Ch. VI), ‘Nazionalismo e patriottismo’, Il Mulino 3, maggio-giugno (1993). The distinction has a longer and problematic history behind. Since its reintroduction in literature by Hans Khon (it was originally proposed by Ernst Troeltsch), it has often been used to distinguish between Western and Eastern forms of nationalism. Hans Khon, The Idea of Nationalism (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1944). Viroli employs it to distinguish between patriotism and nationalism and stress the role of political ties and values against ethno-cultural ties and values. However, I find even Viroli's redefinition both analytically unclear and heuristically unhelpful. First, his account lacks consistency and is often contradictory. Second, he's unable to spell out the dynamics of identification that characterizes and distinguishes patriotism from nationalism. The taxonomy I propose below shows that some ideal-types of patriotism cut across the alleged divide. My account also differs from Viroli in that I do not attempt to connect my defense of Ethical Patriotism to a republican conception of liberty as non-domination. The value I attribute to participation rests on its educational and identity-building force. This point cannot unfortunately be dealt properly here.

21. As Alasdair MacIntyre puts it, ‘What I am […] is in key part what I inherit, a specific past that is present to some degree in my present. I find myself part of a history and that is generally to say, whether I like it or not, whether I recognize it or not one of the bearers of a tradition,’ After Virtue, 221. Similar claims are stated by Michael Sandel, ‘As a self-interpreting being, I am able to reflect on my history and in this sense to distance myself from it, but the distance is always precarious and provisional, the point of reflection never finally secured outside the history itself’ ‘The Procedural Republic’, 91.

22. Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue, 33–4.

23. Michael Sandel, Liberalism, 179.

24. Michael Sandel, America's Search, 74.

25. Charles Taylor in discussing the politics of equal recognition for different culture seems to arrive to just such an attribution of rights, and noticing the paradox refuses to move further stating, ‘I am not sure about the validity of demanding this presumption as a right. But we can leave this issue aside, because the demand made seems to be much stronger’, ‘The Politics of Recognition’, 68.

26. The only reference I was able to find on this point is two brief passages in Michael Sandel, Liberalism, 63.

27. Michael Sandel, Liberalism, 150. To ‘discover’ the constitutive attachments of the self is, according to A.D. Smith, a process akin to founding out who we really are, and is epitomized by Oedipus’ tragic discovery of his identity: ‘Oedipus has a series of such role-identities—father, husband, king, even hero. His individual identity is, in large part, made up of these social roles and cultural categories—or so it would appear until the moment of truth. Then his world is turned upside down, and his former identities are shown to be hollow,’ National Identity, 3.

28. This seems to be the view subscribed by Ernest Renan for whom, ‘More valuable by far than common customs posts and frontiers conforming to strategic ideas is the fact of sharing, in the past, a glorious heritage and regrets, and of having, in the future, [a shared] program to put into effect.’ ‘What Is a Nation?,’ in Becoming National, ed. G. Eley and R.G. Suny (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), 52. The civic approach rests on what Bhirkhu Parekh calls a constructivist view of identity—‘a view which opposes both volitionalist and substantialist conceptions.’ ‘Discourses on National Identity’, Political Studies 42, no. 3 (1994): 504. Such a constructivism is epitomized by G.H. Mead. Mind, Self, and Society (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1934), and more recently by Alberto Melucci, ‘The Process of Collective Identity’, in Social Movements and Culture, ed. H. Johnston and B. Klandermans (London: UCL Press, 1995), 41–63.

29. See Georg Simmel, ‘The Intersection of Social Spheres’, in Georg Simmel: Sociologist and European, ed. P.A. Lawrence (Sunbury-on-Thames: Nelson, 1976), 95–110.

30. Nenad Miščević claims that the communitarians’ epistemology of the self supports a move from identification to identity. ‘Is National Identity Essential for Personal Identity?’, in Nationalism and Ethnic Conflict, ed. Nenad Miščević (Chicago, IL: Open Court), 239–57. In my opinion civic patriotism suggest the need to operate a shift in reverse from identity to identification.

31. Here I follow the non-essentialist reading of Rousseau suggested by Viroli, For Love of Country.

32. Michael Sandel, ‘The Procedural Republic’, 91.

33. As Friedman notes, Michael Sandel's and Charles Taylor's positions are more ambiguous. On the one hand, they base their critique of liberal deontology on a strong notion of community as constitutive of the self. When developing the positive aspects of their public philosophy, this conception of community is, on the other hand, revised to support multicultural political arrangements. ‘The Politics of Communitarianism’. Although, there is no room here to argue it properly, the same basic charge could apply to Michael Walzer as well. Cf. Veit Bader, ‘Citizenship and Exclusion: Radical Democracy, Community, and Justice. Or, What is Wrong with Communitarianism?’, Political Theory 23, no. 2 (1995): 211–46. On the similarity and differences between communitarians and liberal nationalists, see also Vincent, ‘Liberal Nationalism and Communitarianism: An Ambiguous Association’, Australian Journal of Politics and History 43, no. 1 (1997): 14–27.

34. Alasdair MacIntyre implicitly assumes that the moral psychology employed to explain group loyalty and allegiance at group-level can also be employed to explain the national patriotism. Such an assumption is deeply problematic, though. As Stephen Nathanson explains,

if his communitarian conception of morality were correct […] the group to which our primary loyalty would be owed would […] be one's family, one's town, one's religion. The nation need not be the source of morality or the primary beneficial of our loyalty. […] the forging of nations has involved a huge effort to overcome the pull of diverse local attachments. Patriotism has had to compete with familial, tribal, racial, religious, and regional identity. Stephen Nathanson, ‘In Defense of “Moderate Patriotism”’, Ethics 99 (1989): 549.

Similar problems affect ethno-symbolists like A.D. Smith, who believe that modern national identities rest on pre-modern ‘ethnic cores.’ The collective identity of people who interact anonymously across community boundaries and that of those who interact non-anonymously in face-to-face contests must necessarily rest on diverse epistemologies of the self. Alasdair MacIntyre has acknowledged the validity of this criticism. Thus, he now maintains that,

the shared public goods of the modern nation-state are not the common goods of a genuine nation-wide community and, when the nation-state masquerades as the guardian of such a common good, the outcome is bound to be either ludicrous or disastrous or both. For the counterpart to the nation-state thus misconceived as itself as community is a misconception of its citizens as constituting a Volk, a type of collectivity whose bonds are simultaneously to extend to the entire body of citizenship and yet to be binding as the ties of kinship and locality. In a modern, large scale nation-state no such collectivity is possible and the pretence that it is always an ideological disguise for sinister realities. Alasdair MacIntyre, Dependent Rational Animals (London: Duckworth, 1999), 132.

This acknowledgment raises, however, two further questions: first, how can we account for modern nationalism? and second, how can we promote patriotic identification within modern nation-states?

35. This change is well presented by Amin Maalouf in his discussion of the hypothetical case of an inhabitant of Sarajevo,

In 1980 or thereabout he might have said proudly and without hesitation, ‘I'm a Yugoslavian!’ Questioned more closely, he could have said that he was a citizen of the Federal Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina, and, incidentally, that he came from a traditionally Muslim family. […] twelve years later […] he might have answered automatically and emphatically, ‘I'm a Muslim!’ He might have grown the statutory beard. He would quickly have added that he was Bosnian, and would not have been pleased to be reminded of how proudly he once called himself a Yugoslavian. If he was stopped and questioned now, he would say first of all that he was a Bosnian, then that he was a Muslim. He'd tell you he was just on his way to the mosque, but he'd also want you to know that his country is part of Europe and that he hopes it will one day be a member of the Union. Amin Maalouf, On Identity (London: Harvill Press, 2000), 11.

36. Charles Taylor, ‘Cross-Purposes’, 196–7.

37. Alasdair MacIntyre, ‘Is Patriotism a Virtue?’, 299.

38. See http://www.bc.edu/bc_org/avp/cas/his/CoreArt/art/neocl_dav_oath.html

39. Anthony Smith, National Identity, 78. Smith also, notes that the contrast between family ties and patriotic sentiments also entails a conflict between gender-based worldviews, that between an ethics of duty and an ethics of care.

40. Sometimes, these two distinctions support opposite claims. For instance, according to Viroli: ‘Patriotism as the “love of political institutions,” the “common liberty of a people,” or “the republic” is exclusively civic or political and completely opposed to nationalism, which was forged in late 18th century Europe, assuming the existence of or striving for linguistic, cultural, religious, ethnic, or even racial unity, homogeneity, and purity,’ Veit Bader, ‘For Love of Country’, Political Theory 27, no. 3 (1999): 380. Reversing Viroli's reading, Bar-Tal contends that, ‘Nationalism relates to a specific content, focusing entirely on the fundamental goal to have a separate, distinct and independent nation-state […] in contrast, patriotism does not dictate the nature of political organization to a group. It is a more general and basic sentiment,’ Bar-Tal ‘Patriotism as Fundamental Beliefs of Group Members’, Politics and the Individual 3, no. 2 (1993): 51.

41. Leonard Doob, Patriotism and Nationalism (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1964), 128. As with Kohn's even this psychological distinction has a longer history behind. Similar claims were in fact put forward by J.S. Mill in his A System of Logic (London: Routledge, 1843), VI, §5, 561.

42. R. Kosterman and S. Feshbach, ‘Toward a Measure of Patriotic and Nationalistic Attitudes’, Political Psychology 10, no. 2 (1989): 271.

43. To limit myself to Viroli's, he first claims that ‘The theorists of republican patriotism attribute to the republic, viewed as a set of political institutions and ways of life based on these institutions, the highest political value’; two paragraphs later he points out that ‘this does not mean, however, that the republic is purely or essentially political, as distinct from the nation as a cultural entity’; and then clarifies that ‘This does not also mean that the idea of nation or the principle of nationality are opposed to republican patriotism,’ Viroli, Repubblicanesimo, 77, 78 (translation by the author, emphasis in original).

44. As Bader puts it discussing Viroli, ‘cultural diversity is good, unity is bad; patriots are the good guys and nationalists the bad ones,’ ‘Love of country,’ 383. Similar criticisms can be moved against attempts to distinguish between ‘genuine’ and ‘pseudo’ patriotism—T.W. Adorno, E. Frenkel-Brunswik, D.J. Levinson, and R.N. Sanford, The Authoritarian Personality (New York: Harper and Row, 1950)—or blind and enlightened patriotism—R.T. Schatz, E. Staub and H. Lavine, ‘On the Varieties of National Attachment: Blind versus Constructive Patriotism’, Political Psychology 20, no. 1 (1999): 151–74. The taxonomy proposed not only aims at defending a preferred ideal-type of patriotism, Ethical patriotism, but also at separating and re-evaluating Protective and Hegemonic forms from their association with Jingoistic modes of identification.

45. Especially so when we use, as we currently do, the word ‘nation’ to refer to a nation-state. On the evolution of the term nation from its Latin origins indicating a non-political ‘native community of foreigners’—something larger than a family but smaller than a clan (stirps) or a people (gens)—to its actual meaning referring to extended territorial states ruling over allegedly homogeneous ethnic groups, see Zernatto, ‘Nation: the History of a Word’, Review of Politics 6, no. 3 (1944): 351–66.

46. Polities like Athens and Sparta, civitas like Rome and Alba and the Italian Renaissance republics are notable historical examples. As Viroli himself notes, Florentine 15th century patriotism was also a celebration of the city's military and civic superiority. The Florentine expression ‘better a dead corpse inside than a Pisan outside your door’ still in use today is a graphic indication of inter-communal hatred between Italian principalities and republics. Alasdair MacIntyre also notes that:

A variety of such peoples—Scottish Gaels, Iroquois Indians, Bedouin—have regarded raiding the territory of their traditional enemies […] as an essential constituent of the good life; whereas the settled urban or agricultural communities which provide a target for their depredation have regarded the subjugation of such peoples and their reduction to peaceful pursuits as one of their central responsibilities. Alasdair MacIntyre, ‘Is Patriotism a Virtue?,’ 289.

The essays collected in Ethnicity. Theory and Experience, ed. N. Glazer and D. Moynihan (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1975), supply plentiful other examples—see in particular Horowitz's contribution to the volume.

47. This is eminently the case of Chantal Mouffe, who superimposes the Schmittian account to a polycentric model of identity very much like the one I advocate here. Cf. Chantal Mouffe, The Return of the Political (London: Verso, 1993).

48. For non-Western examples, see in particular the Makario Sakay's Republic of Katagalugan, Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities, 154.

49. As Benedict Anderson notes, ‘official nationalism was typically a response on the part of threatened dynastic and aristocratic groups—upper classes—to popular vernacular nationalism. Colonial racism was a major element in that conception of “Empire” which attempted to weld dynastic legitimacy and national community,’ Imagined Communities, 150. On nationalism as a strategy of internal and external colonization, see T.K. Oomen, Citizenship, Nationality and Ethnicity (Cambridge: Polity, 1997) and Bhikhu Parekh, ‘Reconstituting the Modern State’, in Transnational Democracy: Political Spaces and Border Crossings, ed. J. Anderson (London: Routledge, 2002), 39–55. The social Darwinian attempts to establish cultural hierarchies among peoples, races and social classes in the second half of the 19th century are the ironic target of Matthew Kneale's novel English Passengers.

50. Cf. A.W. Marx, Faith in Nation. Exclusionary Origins of Nationalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003).