Background

: Emergency physicians see many people who present to the emergency department stating that they are immunized against tetanus, when in fact, they are not. The patient history is not dependable for determining true tetanus status and simple patient surveys do not provide actual prevalence. The objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of tetanus status by antibody titer seropositivity and quantify such status among patients reporting tetanus protection.

Methods

: This study is a single center prospective convenience sample of patients presenting to the emergency department 12 years of age or older. Patients deemed study candidates and willing to be in the study filled out an eight-question questionnaire that included the question ‘is your tetanus shot up to date’. A blood sample was then drawn for tetanus antibody titer and quantified according to a pre-determined cutoff for protection.

Results

: A total of 163 patients were enrolled. Of patients responding yes to the query ‘is your tetanus shot up to date’ 12.8% (N=5) of them were not seropositive. Of the 26 people who were seronegative in the study all had been to a doctor in the past year and 88.5% (N=23) had been to their family physician.

Conclusion

: The study suggests that it may be difficult to trust the tetanus immunization history given by patients presenting to the emergency room. The study also observed that a large percentage of patients who were serenegative were seen by a primary care physician and not had a necessary tetanus immunization.

Tetanus is a disease in which the spores of Clostridium tetani are introduced into the human body most often through a wound. The spores then germinate under anaerobic conditions and produce the two toxins tetanosposmin and tetanolysin. Tetanospasmin travels from the inoculation site via retrograde axonal transmission and binds irreversibly at the spinal cord and brain. The toxin blocks neuronal release of neurotransmitters. The neurons that release inhibitory neurotransmitters are particularly susceptible to tetanospasmin. The result is painful and a potentially lethal generalized muscle spasm Citation1.

As physicians, tetanus is a disease that is thought about often, vaccinated for, and in the United States encountered very rarely today. It is reported less than 50 times a year in the US (average annual incidence of 0.16 cases/million population) Citation2. Worldwide, the annual incidence of tetanus is 0.5–1 million cases per year Citation2. Incidence and mortality has decreased steadily and the difference has been attributed to universal vaccination with the tetanus toxoid that began in the 1940's (diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and whole-cell pertussis vaccine-pediatric [DTP] vaccine) Citation2.

In US emergency rooms access to patient vaccination records is a rare luxury. Other means of obtaining vaccination status have been reported. A study in Iran evaluated the usefulness of a tetanus quick stick, essentially a rapid finger prick test used in the emergency department for determining immunization status Citation3. Results are promising, however, the test is not widely available and the interview of the patient still remains the primary means of determining if a patient is up to date with their tetanus vaccination. According to the CDC, the case-fatality ratio for tetanus was 18% among those with a known outcome Citation2. However, no deaths have occurred among those who were up-to-date with tetanus toxoid vaccination. In addition, 73% of those with known injury information reported an acute injury yet only 37% sought medical care. Patient education is important and knowing that the tetanus vaccine does not result in lifetime immunity makes the date of the immunization extremely important.

The primary focus of the current study was to examine prevalence of tetanus antibody seropositivity among emergency patients perceiving tetanus protection. A significant number of people who present to the emergency department state that they are up to date on their tetanus vaccination Citation4. Actual immunity against tetanus is likely much lower. A study from Australia found that at least half of those over the age of 50 have a concentration of tetanus antitoxin (< 0.15 IU/mL) that are thought to be too low to be protected Citation5. We suspect that a significant number of them have visited their primary physician within the previous year.

Methods

Study design

This cross-sectional study design utilized a single center prospective convenience sample of patients (12 years of age and older) presenting to the emergency department. The study received approval by the hospital IRB. Data collection occurred from April 2006 to November 2007.

This is a community teaching hospital with 410 beds and 85,000 visits per year including more than 25,000 trauma cases per year. Power analysis determined that a sample of 200, allowing for a 15% drop out rate, would be needed to estimate prevalence and conduct subgroup analysis for our descriptive intent. Patients visiting the emergency department at the start of the study were categorized by age groups (0–17: 27%, 18–35: 33%, 36–64: 30%, >64: 10%) to track age distribution during study implementation.

Subjects

The inclusion criteria were patients 12 years of age and older who present to the emergency department on a shift covered by the study investigators. We included the 12–17 year ages in order to expand the target population of wound injuries presenting to the emergency department. A convenience sample of patients selected consecutively on shifts covered by a study physician was conducted for survey enrollment. Patients were excluded if they had dementia or an altered mental status that prohibited a reliable history. Patients were also excluded if they had been involved in a medical or traumatic resuscitation due to potential issues with the ability to understand consent.

Patients deemed candidates for the study (or their parents) were approached by study investigator physicians about taking part in the study. Informed consent was obtained and they were given an eight item questionnaire to fill out without the help of medical staff or people accompanying them (Appendix 1). The questionnaire had not been previously validated. The nursing staff then collected a one-milliliter blood sample by peripheral venipuncture for a tetanus antibody titer. The questionnaire was collected during the same shift. The blood sample was sent to ARUP laboratories to be analyzed. ARUP Laboratories is a national clinical and pathology reference laboratory (University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT). ARUP labs use Muiti-analyte Fluorescent Detection for the tetanus antibody titer.

Procedures

The Laboratory uses Multi-analyte Fluorescent Detection for the tetanus antibody titer. A concentration of greater than 0.01 IU/ml is considered a protective concentration of tetanus antibody. The sensitivity of Multi-analyte Fluorescent Detection in the ARUP lab is 93.2% and the specificity is 95%. The lab and its performance with Multi-analyte Fluorescent Detection of the tetanus antibody were validated against the standard set by the World Health Organization Citation7. The serology department at the study hospital collected the results from ARUP labs. These results were then paired with the patient questionnaires for final analysis.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the prevalence of seropositivity among patients presenting to the emergency department who perceive being protected against tetanus. Secondary outcomes were the prevalence of people who are seronegative who have visited their primary physician within 10 years and mean duration of time since visiting a primary care physician in patients who are seronegative. Frequency distributions were calculated for each question and comparisons of subgroups were analyzed by the Chi-square statistic (p-value 0.05).

Results

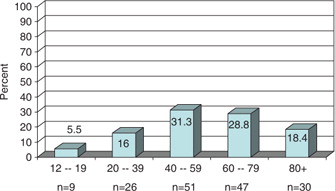

The total number of people in the final survey was 163. Middle age was the predominant age category (). The majority of respondents were female (n=98 or 60%). Distribution of subjects by age categories is in Table 1. The largest category was the 80 years and older with 30 subjects (18.4%) participating.

Table 1. Protection by age and gender distribution

Laboratory tests demonstrated a seronegative (titer 0–0.09 IU) prevalence of 16% (n=26) and seropositive (title >0.1 IU) prevalence of 84% (n=137). The youngest age groups tended to be fully protected while the older age groups tended to have significant proportions unprotected (see Table 1). There was no difference in mean titer levels between genders (males=1.86, females=1.83; p=0.56).

There was no correlation between seropositivity and previous visit with a physician (r=0.11, p=0.16). Of the patients who were seronegative, and therefore requiring a tetanus booster, all (100%, n=26) reported having visited a physician in the past year.

Of the patients who assumed their tetanus protection was current (received within the previous 10 years), 12.8% (n=5) were actually seronegative (Table 2). Of the 31 who believed they were not protected, 64.5% (20) had titers showing they were protected. The sensitivity of self-reported protection was 87% and specificity was 35%. A majority overall (78.4%, n=122) reported that tetanus shots should be updated every 5–10 years (Table 2) and a majority of those seropositive reported a preference for tetanus updates every 5–10 years (84.6%, n=33). The likelihood of reporting that tetanus updates should be every 5–10 years did not differ by gender (males 12.3%, females 8.2%; OR=1.6, p=0.34). There were no differences in belief about keeping ones tetanus protection current based on titer status. Those who reported being protected were no more likely to assert that tetanus status should be kept current than those who reported being unprotected (OR =, p=0.). Overall recall of last tetanus shot was split among the time categories (Table 3) with 13.5% reporting that they did not recall when they had it. A slight majority (50.9%) reported that it was at the family doctor's office where they received it (Table 3). Among those who were seropositive (n=127), 15.7% (n=20) erroneously thought that they lacked protection. A large majority of the positive group were uncertain of their protection status (n=83, 65.4%) Those who were confident of their lack of protection were indeed more likely to be seronegative (35.5%) compared to those who were unsure of their protection (10.8%) [Relative Risk Difference=69.5%, p=0.0018].

Table 2. Perceived protection

Table 3. Tetanus vaccine history

A majority (93.3%) overall reported that they had seen their doctor within the last year yet the majority also reported that their physician did not inquire about tetanus status (Table 4). There was no correlation between the timing of vaccination reported and when patients reported their last visit with a physician was (r=0.097, p=0.25). Among patients who were seronegative (n=26) all reported visiting their physician within the past year and a majority (88.5%, n=23) identified the doctor as a primary care physician.

Table 4. Perceptions about physician encounters

Discussion

Since the 1940's annual reports of tetanus have been reduced by 96% in the United States due to use of the tetanus vaccine and the tetanus toxoid Citation2. More recently, Gergen et al. showed in a serologic survey that 69.7% of Americans six years of age and older are seropositive Citation5. However, depending on actual age, this percentage can vary greatly. For instance, among those greater than 70 years of age only 27.8% of Americans have seroprotective tetanus antibody levels Citation2. Talan et al. demonstrated that even in emergency departments, in which there is an awareness of current standards established by the CDC for tetanus vaccination in patients with wounds, they fall short of proper tetanus prophylaxis Citation6. This was particularly the case when involving patients who qualify for tetanus immunoglobulin.

In the United States, the elderly population, immigrants and intravenous drug abusers are all patient populations that have been found to have negative seropostivity for tetanus Citation2 Citation6 Citation7. With the ever-increasing number of geriatric patients presenting to the emergency department it seems of obvious importance to improve awareness of this disease and be more aggressive with vaccination.

Awareness of tetanus status was an issue among the current study population. The findings suggest that at least 12% of seronegative individuals are under the false impression that they are protected. If injured, this proportion of people would not get immunized by standard practices. This brings forth the point of our study, that without immunization records it is difficult to trust the history a patient provides in regards to tetanus immunization status. The decision for emergency physicians is whether to vaccinate all individuals with wounds regardless of the history provided. The tetanus vaccine is fairly inexpensive (approximately €15 to hospitals) and is easily given. Even so, this does not eliminate the need for a thorough patient history as some individuals will also require the tetanus immunoglobulin.

The study findings also highlight a total seropositive prevalence of 84%. This should be noted because it is slightly higher than previous larger studies such as Gergen Citation5, which demonstrated an overall seropositivity closer to 70%. The difference in prevalence may be due to differences in immigrant populations, differences in primary care practices, or possible differences in laboratory equipment. The current practice guidelines as mentioned in American Academy of Family Physicians recommends a tetanus booster every 10 years, a primary series if not done previously and a ‘do not administer’ if life expectancy is less than two years Citation8. Also of note is that the Gergen study used 0.15 IU/ml as a positive result for seropositivity as compared to the use of 0.1 IU/ml by ARUP laboratories and this study Citation5.

Broad generalization from this study is limited by its use of a convenience sample of patients and having been conducted at a single community hospital center. The type of patients presenting during enrollment periods of study physician coverage could have influenced the outcome. However, its findings reflect this community and are generalizable to the typical Midwestern, middle class community. If replicated, the most important modification would be to conduct a multi center study that includes urban hospitals with random selection of patients across all shifts. This would provide a broader picture of tetanus protection awareness.

Conclusion

Tetanus immunization history in patients presenting to the emergency department is not accurate. Tetanus immunization protocols and hence practices may need to be modified to protect the public from unavoidable error in the current tetanus immunization decision tree.

Conflicts of interest and funding: This study was, in part, supported by Sanofi Pasteur. The data management and analysis was independent of Sanofi and Sanofi had no part in the writing of the manuscript.

Appendix 1

Is your tetanus shot up to date?

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

When was your last tetanus shot?

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

How often do you think it is recommended a tetanus shot should be updated?

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Where did you last get your tetanus shot?

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

When was the last time you went to a doctor?

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Before today's Emergency Room visit, what type of doctor have you last visited for care?

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

When was your last visit to your family doctor?

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

During your last visit to a doctor did they ask you if you were up to date on your tetanus shot?

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Acknowledgements

We would like to give special thanks to Paul Schutt for the organization of the data and also to Sanofi Pasteur for the monetary grant for Dr. Moore's research independent of the pharmaceutical industry.

References

- Wells CL, Wilkins TD. Medical Microbiology. 4th ed. Baron S,. Galveston TX: University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, 1996.

- Pascual FB, McGinley EL, Zanardi LR, Cortese MM, Murphy TV. Tetanus Surveillance—USA, 1998–2000. In: CDC surveillance summaries; 2003 June 20. MMWR. 2003;52(Suppl 3)::1–8.

- Hatamabadi H, Abdalvand A. Tetanus quick stick as an applicable and cost-effective test in assessment of immunity status. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2011;29:717–720.

- Heath TC, Smith W, Capon AG, Hanlon M, Mitchell P. Tetanus immunity in an older Australian population. Med J Australia. 1969; 164: 593–96.

- Gergen P, McQuillan G, Kiely M, Exxati-Rice T. A population-based serologic survey of immunity to tetanus I the United States. NEJM. 1995; 332: 761–66.

- Talan DA, Abrahamian FM, Moran GJ, Mower WR. Tetanus immunity and physician compliance with tetanus prophylaxis practices among emergency department patients presenting with wounds. Ann Emerg Med. Mar. 2004; 43(3): 305–14.

- Bowie C. Tetanus Toxoid for adults—too much of a good thing. Lancet. 1996; 348: 1185–1186.

- Spalding MC, Sebesta SC. Geriatric screening and preventive care. American Academy of Family Physicians. 2008. (July);78(2): 206–215.