Abstract

This article is a review of the PhD thesis undertaken by Joanna Vearey that explores local government responses to the urban health challenges of migration, informal settlements, and HIV in Johannesburg, South Africa. Urbanisation in South Africa is a result of natural urban growth and (to a lesser extent) in-migration from within the country and across borders. This has led to the development of informal settlements within and on the periphery of urban areas. The highest HIV prevalence nationally is found within urban informal settlements. South African local government has a ‘developmental mandate’ that calls for government to work with citizens to develop sustainable interventions to address their social, economic, and material needs. Through a mixed-methods approach, four studies were undertaken within inner-city Johannesburg and a peripheral urban informal settlement. Two cross-sectional surveys – one at a household level and one with migrant antiretroviral clients – were supplemented with semi-structured interviews with multiple stakeholders involved with urban health and HIV in Johannesburg, and participatory photography and film projects undertaken with urban migrant communities. The findings show that local government requires support in developing and implementing appropriate intersectoral responses to address urban health. Existing urban health frameworks do not deal adequately with the complex health and development challenges identified; it is essential that urban public health practitioners and other development professionals in South Africa engage with the complexities of the urban environment. A revised, participatory approach to urban health – ‘concept mapping’ – is suggested which requires a recommitment to intersectoral action, ‘healthy urban governance’ and public health advocacy.

This article has been commented on by Françoise Barten. Please follow this link http://www.globalhealthaction.net/index.php/gha/article/view/7290 – to read her Commentary.

Urban health

“Urban health concerns itself with the determinants of health and diseases in urban areas and with the urban context itself as the exposure of interest. As such, defining the evidence and research direction for urban health requires that researchers and public health professionals pay attention to theories and mechanisms that may explain how the urban context may affect health and to methods that can better illustrate the relation between the urban context and health.” (1, p. 342)

Understanding how to ensure and sustain the health and health equity of urban populations is of increasing importance as over half of the world population is now urban Citation13. Urbanisation is taking place rapidly across Africa, with 50% of the continent expected to be residing in urban areas by 2030 Citation13. South Africa has experienced a faster rate of urbanisation compared to neighbouring countries, with almost 60% of the population estimated to be urban Citation14. This process of urban growth is accompanied by in-migration from within the country (internal migration) and across borders (cross-border migration). Urban growth places pressure on limited, well-located and appropriate housing, resulting in the development of informal settlements within and on the periphery of urban areas. In addition to the multiple exposures to a variety of health hazards in informal settlements, HIV presents a contextual challenge, particularly in South Africa where the highest HIV prevalence is found within urban informal settlements Citation15. South African local government has a ‘developmental mandate’ that calls for government to work with citizens to develop sustainable interventions to address their social, economic, and material needs Citation16. This requires local government to address the challenges of urban growth, migration, informal settlements, and HIV as outlined above Citation17–Citation19. The current (2007–2011) South African National Strategic Plan for HIV signalled a welcome shift in HIV policy, with recognition of the role of government in ensuring that Citation1 internal and cross-border migrant groups and Citation2 residents of informal settlements are able to access the continuum of HIV-related services, which includes prevention, testing, support, treatment, and access to basic services. However, guidelines are lacking to assist local government in addressing HIV-related concerns with migrant groups and in informal settlements at the local level. As a result, migrant groups and residents of informal settlements struggle to access HIV-related services, including health care, antiretroviral treatment (ART), adequate housing, and basic services such as water, sanitation, and refuse removal. Given the developmental mandate of local government in South Africa Citation16, this raises the question that I explore in my PhD: how should local government respond to the urban challenges of migration and informal settlements in the context of high HIV prevalence?

This article presents the findings from my PhD research, which explores the urban health complexities of the (in)famous city of Johannesburg, South Africa Citation20–Citation23. The PhD focuses on exploring four themes, Citation1 rights to the social determinants of health, Citation2 urban livelihoods, Citation3 policy and governance, and Citation4 urban methodologies. A series of five papers contribute to the PhD study, a summary of these papers and the research themes is displayed in .

Table 1. The key themes covered in the PhD thesis and associated papers

Data and methods

In order to engage with the complexity of Johannesburg and to explore the diverse experiences of poor urban migrant groups, my research spans from the central city through to the periphery. This includes exploring the urban experiences of the (mostly cross-border) migrant population living in the dense, overcrowded, central-city suburbs of Hillbrow and Berea. I also explore the experiences of non-migrants and (predominantly internal) migrants who enter the city and settle within the currently shifting suburbs of Jeppestown and Benrose to the south-east of the central-city; an area constructed through a range of linked ‘hidden spaces’ that include dilapidated single-sex hostels, shack farms (shacks inside abandoned factory buildings), informal settlements, and sub-divided houses and flats. A third urban experience is found through the residents of the peripheral informal settlement of Sol Plaatjies, located to the south-west of the city centre. I also explore the experiences of migrants living with HIV as they attempt to access ART in the inner-city. In addition, I evaluate the attempt of local government to respond to HIV within urban informal settlements. Four studies were undertaken that focus on: migrants (internal and cross-border); residents of the central-city; residents of a peripheral informal settlement; health care providers involved in the provision of ART; and stakeholders involved in designing and implementing local responses to migration and informality in the context of HIV. Further details relating to the respective methodologies can be found in the associated papers.

Assessing non-citizen access to ART in Johannesburg inner-city (paper I)

Exploring the tactics of urban migrants (paper II)

Migration, housing, HIV, and access to health care: comparing urban formal and informal (paper III)

Evaluating a local level developmental approach to HIV in informal settlements (paper V)

Findings

Urban health and development challenges

Through synthesising the findings of the four studies, I identified six central urban health and development challenges (see and paper III) Citation21. I propose that exploring these six challenges assists in understanding the components of urban vulnerability; the characteristics of urban vulnerable groups, their urban setting (location), and how urban inequalities lead to poor health outcomes. I argue that any attempt to improve – and sustain – the health of urban populations requires that local level policy makers and practitioners understand, engage with, and address these six challenges Citation21.

Table 2. Developing country urban contexts present six central urban health and development challenges Citation21

Paper I Citation22 explores several of these central challenges. Through exploring how different migrant groups struggle to access antiretroviral (ART) services in public sector clinics in the inner-city of Johannesburg, an example of how migration has implications for urban health is presented Citation22. The research presented in paper I outlines how the urban health needs of migrant residents can remain unmet, through challenges with access to documentation and the inconsistent application of national legislation at a facility level. Paper I highlights the challenges of urban inequalities, migration, ‘weak rights to the city’ (Citation24, p. 13), and – for many migrants attempting to access ART – the negative impact of struggling to access services on their health and their livelihoods.

Navigating the city: lived experiences of urban migrants and implications for urban health

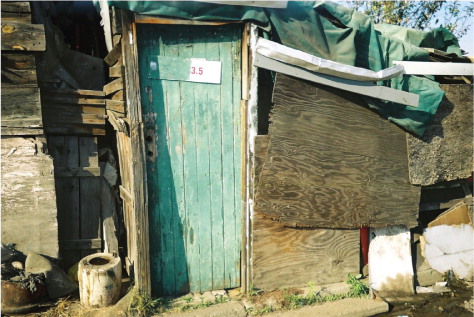

Paper II explores the ways in which internal South African migrants find ways to navigate the central city through residing in what I term ‘hidden spaces’ Citation20 ().

Figure 1. This hidden space in inner-city Johannesburg could be mistaken for a rural area. Residents mostly originate from rural South Africa. © Nathi Makhanya.

The ‘hidden spaces’ described in paper II result in bureaucratic invisibility and illustrate the challenges faced by local government practitioners: the mandate to provide services to those urban populations who wish to remain hidden as well as to those urban populations who are hidden yet wish to ‘be seen.’ It is important for urban practitioners to understand and consider the social production of space, and the flow of urban spaces Citation20. The city is a fluid concept, where spaces can be converted and recycled to suit the needs of different urban residents. The city can be understood through people's experiences, made up of underlying structural social and economic factors, individual perceptions, and spatial practices. In this respect, considering de Certeau's concept of ‘spatial stories’ is useful Citation26. This concept considers how different social actors make space for themselves in urban spaces. These ‘spatial stories’ create maps that are known only to the urban resident, evading the officialdom of the maps of town planners and city authorities. Such ‘artful manoeuvres’ of individuals – everyday users – enable social actors to slip ‘between the lines, vanishing out of sight’ (Citation27, p. 114). Such ‘ways to insert oneself into the local society’ enable residents to ‘enter into a certain kind of relationship with a physical and human environment that are based on the negotiation of ways of insertion and cohabitation’ (Citation28, p. 27). Such practices enable residents to ‘invent the city as they slip into its mould, subjected to it but constantly reproducing/changing it’ (Citation28, p. 28). In this way, city residents represent ‘much more than the city’ (Agier 1999 as cited in Ref. Citation28, p. 27). Paper II attempts to emphasise the interdisciplinary nature of urban health Citation20. Urban health researchers, policy makers, and practitioners must be aware of the complexities presented within the urban context and the tactics employed by urban populations. This requires the involvement of and engagement with a range of disciplines including anthropology, urban studies, social science, geography, and political science. It is essential that urban practitioners engage with the multiple complexities present within cities in order to develop the most appropriate responses.

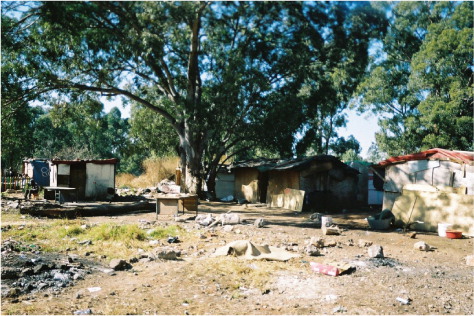

Place matters

Paper III explores urban inequalities in Johannesburg Citation21. Key differences were found between the social determinants of health in a peripheral informal settlement and the central-city. Migration status is shown to be a key determinant of urban health as internal South African migrants are significantly more likely to enter the city and locate in peripheral urban informal settlements. Paper III highlights that internal migrants residing in the peripheral informal settlement are worse off than cross-border migrants residing in the central-city; internal migrants experience a range of challenges associated with residing on the periphery of the city. In particular, access to basic services – such as water, sanitation, and refuse collection – are inadequate ().

Figure 2. Inadequate sanitation is a reality where these spaces remain hidden from state service provision. © Nathi Makhanya.

Households in the informal settlement are more likely to have children, are larger in size than those of cross-border migrants residing in the inner-city, and are cramped into small informal houses. Residents are more likely to be without an income, rely on informal, survivalist livelihood strategies, and experience food insecurity. Given that urban informal settlements are associated with the highest HIV prevalence nationally, it is essential that local and provincial government ensure that the full spectrum of HIV related health care and social services are available and accessible for those residing in the urban periphery. This includes access to the spectrum of HIV services, including access to ART ().

The role of local government in developing appropriate urban health responses

Local governments experience the impact and effects of migration, informal settlements and a high HIV prevalence; ‘it is local governments and service providers who must channel resources to those in need, and translate broad objectives into contextualised and socially embedded initiatives’ (18, p. 177). It is essential that local government is able to respond to these challenges in an integrated way. South African local government has a ‘developmental mandate’ – a ‘local government committed to working with citizens and groups within the community to find sustainable ways to meet their social, economic and material needs and improve the quality of their lives’ (16, p. 23). The developmental mandate requires local government to inter alia address the challenges of urban growth, migration, informal settlements, and HIV Citation17–Citation19 Citation29 Citation30. Importantly, a ‘developmental mandate’ highlights the need to establish partnerships across local government departments; achieving this

“… means thinking beyond the narrow confines of a set of delinked service sectors. The White Paper explicitly recognises that South African municipalities, like counterparts in other parts of the world, are responsible for managing space occupied by people: the challenge was no longer only how to provide a set of services, but how to transform and manage settlements that are amongst the most distorted, diverse, and dynamic in the world.” (18, p. 169)

Urban health models: engaging with complexity

Various models of urban health have been developed that aim to assist in understanding the impact of city living on urban health, several of which draw on the concept of social determinants of health Citation2–Citation5 Citation8 Citation34–Citation38. I focus on three models within my PhD that build on the social determinants of health framework. The three frameworks are Citation1 the ‘urban living conditions model’ Citation4, Citation2 The WHO CSDH conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health Citation8, and Citation3 the conceptual framework of the associated WHO Knowledge Network on Urban Settings Citation5. None of these frameworks are utilised by South African government at either the national or local levels.

I applied the findings from the four studies to critique these existing urban health models; I argue that these frameworks are unable to engage adequately with the complexities of specific developing country urban contexts Citation21. In particular, I argue that current frameworks do not deal adequately with what I consider to be the key – and interlinked – challenges of migration and informal settlements in a context of high HIV prevalence. A central limitation of the existing frameworks is that – by definition – frameworks provide ‘an oversimplification of a complex reality and should be treated merely as a guide or lens through which to view the world’ (39, p. 8). As a result, the existing frameworks lack adequate suggestions for where and how to intervene in order to improve the health of a specific urban population and cannot provide guidance about who should intervene.

In my review of existing urban health frameworks, I have struggled with what I consider to be a central limitation of all the urban health frameworks reviewed: that they fail to engage with the specific complexities of a given urban context (such as Johannesburg, for example). Importantly, the existing urban health frameworks do not adequately engage with the importance of effective governance at a local level, including the critical role of local government in planning for – and implementing – interventions to address urban public health (as emphasised by 9, 10–12, 40). In particular, this relates to the role of good governance (including local government activities) in improving health equity in urban contexts. A central limitation here is the role of local government in implementing effective urban development policy that engages with: urban governance, community participation, and decentralisation (see 40).

Whilst the existing frameworks are themselves complex and engage with the multiple levels and determinants that ultimately impact health outcomes, frameworks are – by definition – generalised and therefore unable to engage with the specific complexities present within a particular urban context. Rakodi usefully summarises my frustrations by explaining that

“Inevitably, any diagram, or indeed any framework, is an oversimplification of a complex reality and should be treated merely as a guide or lens through which to view the world. Its value lies in its ability to capture key components and their interrelationships as a starting point for identifying critical analytical questions and potential leverage points where intervention might be appropriate – not in whether it portrays the whole of reality, everywhere and at all times, but whether it provides insightful analysis and appropriate action.” (39, p. 8)

A revised approach to urban health?

Accepting that frameworks can be the starting point for identifying leverage points Citation39, responding to urban health challenges requires going further than a framework approach. At the start of my PhD, I had anticipated generating a revised urban health framework that would capture the complexity of the urban context and provide suggestions for effective intervention to improve the health of urban populations. However, I have realised that a revised framework will not allow me to achieve this aim, and would lead to another ‘static’ representation of a complex urban context. In order to achieve the overall aim of my research, I require a conceptual tool that will facilitate a process for change at the local level, and will enable local government to respond appropriately to improve the health of urban populations. As a result, I am suggesting a move away from a framework for urban health, to a more fluid ‘concept map’ Citation41 Citation42.

“Concept maps are graphical tools for organizing and representing knowledge. They include concepts, usually enclosed in circles or boxes of some type, and relationships between concepts indicated by a connecting line linking two concepts. Words on the line, referred to as linking words or linking phrases, specify the relationship between the two concepts.” (41, p. 1)

The concept mapping method is designed around a participatory process to strengthen the developmental mandate of local government; this requires for the IDP process to be effectively implemented Citation32. It is suggested that the concept mapping process will support and inform the IDP process, ensuring that local government achieves its developmental mandate, and that urban health is approached in a developmental, interdisciplinary, and participatory way. I think that a strategic person would need to be appointed by local governments to drive this process. This individual would require research skills, both in conducting and commissioning research and in engaging with and interpreting research findings. The concept mapping process does rely on local government assessing its urban context; without such knowledge, the concept mapping would be based on assumed knowledge relating to the needs and locations of urban poor groups. Linked to this, it is anticipated that the concept mapping process will enable local government to reflect on its own interventions and learn from good practice. Therefore, as local government assesses its urban context, it must also evaluate and learn from current local government interventions. This individual would work with the IDP Manager and HIV coordinator to drive the concept mapping process, which would then feed into the IDP process itself.

Conclusion

Urban populations are heterogeneous and city-residents live diverse urban experiences within different places in the city Citation21 Citation22. It is therefore essential that local urban governments are able to engage with this diversity in order to inform spatially targeted, multi-level, and multi-sectoral urban health responses. Existing urban health frameworks do not deal adequately with the specific complexities of developing country urban environments. In particular, the frameworks have failed to adequately account for guiding local government in responding to the interlinked challenges identified; internal and cross-border migration, informal settlements, and high HIV prevalence. An alternative approach of ‘concept mapping’ to assist local government and other stakeholders in responding to urban health challenges is urgently required. It is suggested that such an approach would enable local government, and other actors – including residents themselves – to engage with the complexities of the urban context in a participatory way and guide the creation of city-specific ‘urban health plans’ that work towards identifying and addressing the specific urban health needs associated with different areas within a city. Intersectoral action, ‘healthy urban governance’ and a return to public health advocacy are considered critical to the effectiveness of such an approach.

It is suggested that the resultant ‘urban health plan’ will assist local government in responding in a developmental way to the interlinked challenges of migration and informal settlements in a context of high HIV prevalence.

Policy recommendations

A new urban development policy that engages with urban governance, community participation and decentralisation is required Citation40. This would involve reviewing all policies that relate to health and housing, in order to determine whether they address the needs of all urban residents and are equity promoting. Importantly, their effective implementation must be monitored and action taken by local government to address challenges. Central here is addressing the challenges that poor urban migrant groups experience in their ability to claim their rights to health care (including ART) and housing Citation21. It is essential that action is taken to improve the environmental conditions of urban informal settlements that negatively affect the health outcomes of those residing there. Local government is required to engage with actions that are beyond the mandate of local government; through an intersectoral approach that encompasses healthy urban governance and public health advocacy, local government should mobilise actors within other spheres of government and civil society to take action as appropriate. Importantly, this identifies the need to implement a ‘social determinants of urban health’ approach within all policy and programming initiatives.

Future research should implement a pilot project to evaluate the effectiveness of the application of ‘concept mapping’ to assisting local level urban health policy makers and planners in developing an ‘urban health plan’ to respond to the interlinked challenges of migration and informal settlements in a context of high HIV prevalence.

Conflict of interest and funding

The author has not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank all participants who generously gave their time to share their urban experiences with me. My PhD supervisors (and co-authors), Dr. Liz Thomas (MRC/Wits) and Dr. Ingrid Palmary (ACMS, Wits) are warmly thanked for their continued support, insight, and friendship. My additional co-authors, Dr. Lorena Nunez and Dr. Scott Drimie are thanked for their energy and engagement throughout the PhD process. The University of the Witwatersrand and Carnegie Corporation of New York are thanked for the AIDS Research Initiative (ARI) PhD bursary that I was awarded.

References

- Galea S, Vlahov D. Urban health: evidence, challenges, and directions. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005; 26: 341–65. 10.3402/gha.v4i0.5898.

- Vlahov D, Galea S, Gibble E, Freudenberg N. Perspectives on urban conditions and population health. Cad Saude Publica. 2005; 21: 949–57. 10.3402/gha.v4i0.5898.

- Freudenberg N, Galea S, Vlahov D. Beyond urban penalty and urban sprawl: back to living conditions as the focus of urban health. J Community Health. 2005; 30: 1–11. 10.3402/gha.v4i0.5898.

- Galea S, Freudenberg N, Vlahov D. Cities and population health. Soc Sci Med. 2005; 60: 1017–33. 10.3402/gha.v4i0.5898.

- WHO. Our cities, our health, our future. Acting on social determinants for health equity in urban settings. Geneva: Commission on the Social Determinants of Health. 2008.

- Vlahov D, Freudenberg N, Proietti F, Ompad DC, Quinn A, Nandi V, Galea S. Urban as a determinant of health. J Urban Health. 2007; 84: i16–i26. 10.3402/gha.v4i0.5898.

- Vlahov D, Galea S. Urbanization, urbanicity, and health. J Urban Health. 2002; 79(4 Suppl 1):S1–S12.

- WHO. Closing the gap in a generation. Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Geneva: Commission on Social Determinants of Health. 2008.

- Szreter S. Mortality and public health, 1815–1914. Refresh. 1992; 14: 1–4.

- Szreter S. Economic growth, disruption, deprivation, disease, and death: on the importance of the politics of public health for development. Popul Dev Rev. 1997; 23: 693–728. 10.3402/gha.v4i0.5898.

- Szreter S. Industrialization and health. Br Med Bull. 2004; 69: 75–86. 10.3402/gha.v4i0.5898.

- Szreter S, Woolcock M. Health by association? Social capital, social theory, and the political economy of public health. Int J Epidemiol. 2004; 33: 650–67. 10.3402/gha.v4i0.5898.

- UNFPA. State of the world population 2007. Unleashing the potential of urban growth. New York: United Nations Population Fund. 2007.

- Kok P, Collinson M. Migration and urbanization in South Africa. Statistics South Africa. Pretoria, 2006

- Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi L, Parker W, Zuma K, Bhana A, Connolly C, Jooste S, Pillay V. South African national HIV prevalence, HIV incidence, behaviour and communication survey, 2005. Human Sciences Research Council. Cape Town, 2005

- The Republic of South Africa. The white paper on local government. Pretoria: The Department of Constitutional Development. 1998.

- Landau LB. Discrimination and development? Immigration, urbanisation and sustainable livelihoods in Johannesburg. Dev South Afr. 2007; 24: 61–76. 10.3402/gha.v4i0.5898.

- Landau L, Singh G. Decentralisation, migration and development in South Africa's primary cities. Migration in post-apartheid South Africa: challenges and questions to policy makers. Notes and documents 38. Wa Kabwe-Segatti A, Landau LAgence Francaise de Developpment. Paris, 2008; 163–211.

- Bocquier P. Urbanisation in developing countries: is the ‘cities without slums’ target attainable?. Int Dev Plann Rev. 2008; 30.

- Vearey J. Hidden spaces and urban health: exploring the tactics of rural migrants navigating the city of gold. Urban Forum. 2010; 21: 37–53. 10.3402/gha.v4i0.5898.

- Vearey J, Palmary I, Thomas L, Nunez L, Drimie S. Urban health in Johannesburg: the importance of place in understanding intra-urban inequalities in a context of migration and HIV. Health & Place. 2010; 16: 694–702. 10.3402/gha.v4i0.5898.

- Vearey J. Migration, access to ART and survivalist livelihood strategies in Johannesburg. Afr J AIDS Res. 2008; 7: 361–74. 10.3402/gha.v4i0.5898.

- Vearey J. Learning from HIV: exploring migration and health in South Africa. Global Pub Health 2011. 10.3402/gha.v4i0.5898.

- Balbo M, Marconi G. Governing international migration in the city of the south. Global Commission on International Migration. Geneva, 2005

- The Republic of South Africa. The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa – No. 108 of 1996. Pretoria: The Department of Constitutional Development. 1996.

- de Certeau M. The practice of everyday life. Translated by Steven Rendall. University of California Press. Berkeley, 1984

- Tonkiss F. Spatial stories: subjectivity in the city. Space, the city, and social theory. Tonkiss F.Polity. Malden MA, 2005; 113–130.

- Bouillon A. Citizenship and the city: the Durban centre-city in 2000. Transformation. 2002; 48: 1–37.

- MRC., INCA., dplg. Handbook for facilitating development and governance responses to HIV/AIDS. South Africa: Medical Research Council. 2007.

- Department of Provincial and Local Government (dplg). Framework for an integrated local government response to HIV and AIDS. Pretoria: dplg.: 2007.

- Nel E, John L. The evolution of local economic development in South Africa, in democracy and delivery. Urban policy in South Africa. Pillay U, Tomlinson R, Du Toit JHSRC Press. Cape Town, 2006; 208–229.

- Harrison P. Integrated development plans and third way politics, in democracy and delivery. Urban policy in South Africa. Pillay U, Tomlinson R, Du Toit JHSRC Press. Cape Town, 2006; 186–207.

- Tomlinson R, Beauregard R, Bremner L, Mangcu X. The post-apartheid struggle for an integrated Johannesburg. Emerging Johannesburg: perspectives on the postaparthied city. Tomlinson R, Beauregard R, Bremner L, Mangcu X.Routledge. London, 2003; 123–147.

- Starfield B. Pathways of influence on equity in health. Soc Sci Med. 2007; 64: 1355–62. 10.3402/gha.v4i0.5898.

- Braveman PA. We also need bold experiments: a response to Starfield's ‘Commentary: pathways of influence on equity in health’. Soc Sci Med. 2007; 64: 1363–86.; discussion 1371–72. 10.3402/gha.v4i0.5898.

- Solar O, Irwin A. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Discussion paper for the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. World Health Organization. Geneva, 2007

- Commission on the Social Determinants of Health. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health: discussion paper for the Commission on Social Determinants of Health DRAFT. Geneva: Commission on the Social Determinants of Health. 2007.

- Diderichsen F, Evans T, Whitehead M. The social basis of disparities in health, in challenging inequities in health. Evans T, Whitehead M, Diderichsen F, Bhuiya A, Wirth M.Oxford University Press. New York, 2001; 13–23.

- Rakodi C. A livelihoods approach – conceptual issues and definitions. Urban livelihoods: a people-centred approach to reducing poverty. Rakodi C, Lloyd-Jones TEarthscan. London, 2002; 3–22.

- van Naerssen T, Barten F. Healthy cities as a politicial process. Healthy cities in developing countries: lessons to be learned. van Naerssen T, Barten FNICCOS. Saarbrucken, 2002; 1–24.

- Novak J, Cañas A. The theory underlying concept maps and how to construct and use them. Technical Report IHMC CmapTools 2006-01 Rev 01-2008. Florida Institute for Human and Machine Cognition. Available from: http://cmap.ihmc.us/Publications/ResearchPapers/TheoryUnderlyingConceptMaps.pdf.

- Huynen M, Martens P, Hilderink H. The health impacts of globalisation: a conceptual framework. Globalization Health. 2005; 1.