Abstract

Background: North-South Partnership (NSP) is the mandated blueprint for much global health action. Northern partners contribute funding and expertise and Southern partners contribute capacity for local action. Potential Northern partners are attracted to Southern organizations that have a track record of participating in well-performing NSPs. This often leads to the rapid ‘scaling up’ of the Southern organization's activities, and more predictable and stable access to resources. Yet, scaling up may also present challenges and threats, as the literature on rapid organization growth shows. However, studies of the impact of scaling up within NSPs in particular are absent from the literature, and the positive and negative impact of scaling up on Southern partners’ functioning is a matter of speculation.

Objective: The purpose of this study is to examine how scaling up affects a Southern partner's organizational functioning, in a Southern grassroots NGO with 20 years of scaling up experience.

Design: A case study design was used to explore the process and impact of scaling up in KIWAKKUKI, a women's grassroots organization working on issues of HIV and AIDS in the Kilimanjaro region of Tanzania. Data included documents, observation notes and in-depth interviews with six participants. The data were analyzed by applying an established systems framework of partnership functioning, in addition to a scaling up typology.

Results: KIWAKKUKI has experienced significant scale-up of activities over the past 20 years. Over time, successful partnerships and programs have created synergy and led to further growth. As KIWAKUKKI expanded so did both its partnerships and grassroots base. The need for capacity building for volunteers exceeded the financial resources provided by Northern partners. Some partners did not have such capacity building as part of their own central mission. This gap in training has produced negative cycles within the organization and its NSPs.

Conclusions: Northern partners were drawn to KIWAKKUKI because of its strong and rapidly growing grassroots base, however, a lack of funding led to inadequate training for the burgeoning grassroots. Opportunity exists to improve this negative result: Northern organizations that value community engagement can purposefully align their missions and funding within NSP to better support grassroots efforts, especially through periods of expansion.

The purpose of this paper is to report the findings of a case study examining the experience of a successful Southern grassroots organization and its partnerships with Northern organizations through a period of growth spanning 20 years.

There is a natural tendency for successful grassroots non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to grow, or ‘scale up’ Citation1. One potential downside to scaling up is loss of contact with the grassroots may threaten the viability of an NGO in the long run Citation2. If NGOs fear such loss of contact with their grassroots, they may avoid growth opportunities, perhaps unwisely if their fears are groundless. Alternatively, it may indeed be the case that growth is a risk factor for loss of the grassroots base, and that growth should therefore be pursued with caution. Empiricism focused on these phenomena is needed to build a knowledge base for better-informed NGO strategic development.

This issue is of special relevance to NGOs in which the grassroots is a vital foundation of existence. Many community-based health promotion and development NGOs in the Global South spring from grassroots concerns, and may therefore need to be especially watchful for any signs of faltering in their grassroots base. In sub-Saharan Africa, many of today's most active and effective NGOs were founded by local people concerned about local health challenges. Among those challenges, the HIV epidemic is especially salient.

While all areas of the globe report HIV infection, sub-Saharan Africa is disproportionately affected. Within Southern Africa, the most marginalized populations are affected the worst. Because of an array of structural and social inequities, women and girls are particularly vulnerable to HIV infection and have a more dismal experience once infected Citation3. In the Kilimanjaro region of Tanzania, a community-based organization run by women, named KIWAKKUKI, has been working for two decades to fight this epidemic, in partnership with many Northern organizations.

The model of Northern organizations partnering with Southern grassroots organizations (GROs) has many staunch advocates Citation4–Citation6. From the perspective of Northern organizations, these organizations are perceived to be better at mobilizing local resources than their Northern counterparts and thus able to operate programmes more cost-effectively Citation7. They are also seen as being more dynamic in the local community, capable of inspiring the trust of local inhabitants, having the ability to work with the most marginalized people in communities in remote areas, and having sensitivity to (possibly volatile) political contexts Citation8 Citation9. GROs are perceived to be able to adapt international programs, exported from other contexts, to conform to local needs and conditions Citation10. Northern organizations have also been motivated to partner with these local organizations in the health and development arena as a strategy to strengthen civil society in the South.

Hoksbergen Citation11 describes the evolution of the discourse on partnership:

One key reason for the new focus on civil society is the gradual transition from seeing development primarily as physical welfare (e.g. levels of income, health education, and lifespan) to an ever-increasing appreciation of development as a process fed by local ownership and committed participation.

On the other hand, Southern GROs seek out partnerships with Northern organizations for different but similarly compelling reasons. First, Northern partners may provide access to enormous funding resources. Northern organizations may offer training and capacity building for Southern partners. Northern partners may also provide support and solidarity for international advocacy on local issues. Northern organizations can often help Southern organizations by linking them to other local and international organizations enabling them to develop their own networks Citation11. In other words, partnerships with Northern organizations can enable small GROs to ‘scale up’ their activities in a number of ways.

One recurrent criticism of the North-South partnerships (NSPs) is that they are ‘rarely subjected to detailed scrutiny’ Citation12. Fowler Citation5 even suggests that adopting partnership as a dominant model may be counterproductive and may erode system credibility and performance. While NSPs, like most individual NGOs, regularly engage in monitoring of their ongoing activities for particular projects (usually in the form of reports produced by the Southern partner) they rarely take time to evaluate the partnerships, that is to assess their performance in terms of results, benefits and costs, and to identify strengths and weaknesses which may affect their effectiveness overall Citation12, Citation13. Clearly case studies are needed which systematically examine North-South partnerships to begin to identify potential strengths and weaknesses in the process of delivering health services through such partnerships.

This paper will present the findings of a case study conducted with KIWAKKUKI, examining their almost 20-year history of collaborating within NSPs. The study particularly focuses on their experience through a scaling-up process enabled by their partnerships with Northern organizations. To improve the utility of this study for purposes of understanding and comparison, a systems framework of collaboration was employed to guide the examination of NSP functioning. We will begin the paper by laying a foundation briefly reviewing the limited literature on NSP, and examining and defining the concept of ‘scaling-up.’ We will describe the analytical framework, the Bergen Model of Collaborative Functioning, used to analyze the data and give some background information about the case, KIWAKKUKI. We will present the findings of the study and then discuss those findings in relation to the literature on NSP, scaling up and the analytical frame.

North-South partnership

Some research on NSP relevant for health promotion has been undertaken, but to find it, one must consult the development literature as very little on this subject is published in the health promotion literature Citation14. However, the development literature has several significant limitations, arising partly because of ambiguity in the use and meaning of the term ‘partnership.’ Authors have been writing about this ambiguity since the term partnership began to appear in the literature in the 1970s. However, there has been no movement toward consensus. Indeed, Harrison Citation16 asserts that part of term's attractiveness ‘lies in its slipperiness.’

Partnership is frequently defined in idealistic terms, for example: ‘The term “partnership” reflects a set of values, typically encompassing equality, transparency, shared responsibility, joint decision making, trust and mutual understanding Citation9.’ Brinkerhoff Citation4 criticizes such idealized definitions because they may not be completely operational, and also may not be applicable in all situations. As Brehm Citation15 pointed out in her review of the NSP literature, such definitions can result in overly pessimistic judgments about the quality of NSPs, given that no actual partnership could stand up to the ideal at all times. Another issue is that much of the literature on NSP is anecdotal, drawn mostly from professional experience, and without an empirical foundation Citation4.

Some of the few case studies of NSPs in the literature report severe power imbalances between Northern and Southern partners. Various authors have found this to have negative implications in terms of agenda setting, accountability, transparency and reporting (Citation6, Citation16–Citation18).

Regarding agenda setting, Harris Citation16 found in her case studies of Cambodian and Filipino NGOs that local organizations were pressured to provide services because funders insisted upon them rather than because those programs were helping the community. She describes three problems: first, the local NGOs face such great needs in their communities they are willing to accept difficult working relationships with their Northern donors to receive funding; second, projects must fall under the funder's priorities and often overlook local needs; and third, funders often write proposals with no consultation or participation of local people. Indeed, Harris found that while funders often espoused values of community participation, they rarely allowed the time required to engage in cultivating such participation.

Harrison (6) who conducted an ethnographic examination of partnership and participation in Ethiopia describes accountability and transparency demands as a ‘one-way street’ from North to South. Similarly, a study of partnership between the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and three Southern non-governmental organizations (SNGOs) in Northern Uganda found that the Southern partners were provided little insight about UNCHR's decision-making processes and outcomes, leaving the Southern partners ‘fraught with uncertainty’ Citation9. In the same study, the SNGOs were accountable to UNHCR to file timely reports and other paperwork, but they had no way to hold UNHCR accountable, as for example when promised funding was delayed (9).

Regarding problems related to proposal writing and reporting, Harris (16) found that local NGOs in Cambodia and the Philippines felt ‘humiliated’ by the proposal writing process. Corbin et al. (19) found that a Northern partner engaged in ‘capacity building’ in Tanzania by requiring their Southern partner to write numerous drafts of a single proposal. The Northern partner later explained that the intention was to improve the organization's ability to write proposals, but the staff of the SNGO reported being made to feel like ‘babies.’

Among the major obstacles to authentic NSP are the internal policies, procedures and cultures of the Northern partners, specifically those related to financial and management controls Citation20. This follows from tension within Northern organizations, between the paradigms of ‘partnership’ with Southern partners and ‘accountability’ within their own organizations. Mawdsley et al. Citation18 details how the ‘new public management’ is being directly exported to the South via NSP relationships in Ghana, India and Mexico. Sanders et al. (14) starkly state that health promotion in Africa ‘is closely linked to its colonial past, dominated by European values and practices.’

While problems of power imbalance and power struggles dominate the discourse on NSP, there are also a few cases reported of NSPs in which power is not so unevenly distributed Citation19 Citation21. Ebrahim examines partnership relationships of two Indian NGOs and found the relationships to be ‘interdependent.’ He describes a more balanced exchange of funds transferred from North to South and reputation/legitimacy transferred from South to North. Previous research on KIWAKKUKI found that having a large grassroots base of volunteers afforded the organization a bit of a counter-balance to the Northern resource contribution Citation19. Additionally, these findings suggest that KIWAKKUKI staff did not see ‘equality’ as a static concept but one that was dynamic with power transferring from their Northern partners at times and from themselves at times. For instance, they had no issue with Northern partners requiring reports to track funding, even if the demands were onerous at times. At other times, they felt they had the power in their partnerships when it came to accepting projects according to their strategic plan, since SNGOs, in most cases, have the power to say ‘yes’ or ‘no’ in the first place (19). It may be important to note that both Ebrahim and Corbin et al. conducted case studies of NGOs engaged in ‘successful’ NSPs.

Scaling-up

Uvin Citation10 offers a typology of four possibilities for scaling up. First is quantitative scaling-up, where the SNGO seeks to increase its membership base, thus growing the organization in size and/or geographic reach. The second type, functional scaling up, is when a SNGO expands its activities to include new and different projects or programs. When this is done with Northern funding, SNGOs may gradually find themselves taking on projects for which funding is available instead of concentrating on community needs. The third type is political scaling up and involves a transition of the SNGO from primarily service delivery to advocacy, to affect the underlying causes of the issues addressed by the organization. Uvin cautions that SNGOs that scale up to become more involved in national and international policy, may begin to focus so much on advocacy that they lose their connections to the grassroots. The fourth type is organizational scaling up, which involves building capacity within the SNGO to become more financially diversified, more efficient and effective, improve management, and enhance self-sustainability. Scaling-up in many ways can be seen as inevitable. As Uvin and his colleagues (1) describe ‘In many ways scaling up is a natural, almost organic, process for NGOs. If things are done well, people whether beneficiaries or interested outsiders will ask for more. Leadership, convinced of the importance of its work, typically opts for wider rather than narrower impact.’ Problems reported in the literature on scaling up are similar to those described with NSP generally. Three main concerns are reported. First, SNGOs who scale up to become more involved with international partners may begin to focus more on advocacy and professionalization resulting in a loss of connection to their grassroots Citation22 Citation23. Uvin (10) warns scaling up can sometimes lead an SNGO to ‘soften’ their mission from community empowerment to appease their Northern partners. He also suggests reliance on Northern funding may lead SNGOs to work on projects for which funding is available instead of prioritizing community-identified needs.

Responding to the need for empiricism focused on the phenomenon of SNGO scaling up and possible effects on grassroots, the study reported here examined KIWAKKUKI's experience, using as its analytic framework an established systems model of partnership functioning, the Bergen Model of Collaborative Functioning, abbreviated BMCF Citation24.

The Bergen model of collaborative functioning

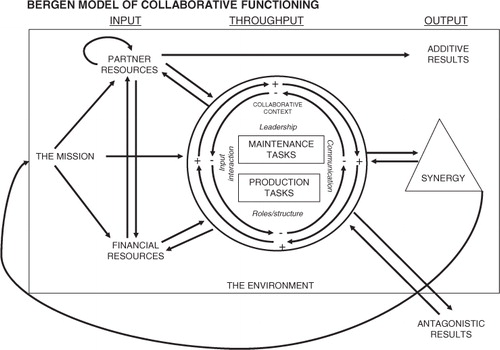

The BMCF is an adaptation of a systems model introduced by Wandersman et al. Citation25. The BMCF was originally drafted using the results from a case study of a global professional collaboration (24). It has since been used to examine a number of different collaborative structures (see Citation26–Citation29). The BMCF () depicts the introduction of inputs (Mission, Partner and Financial Resources) in to the Collaborative Context where Maintenance Tasks which keep the collaboration functioning are pursued alongside Production Tasks which directly serve the collaborative Mission. Four crucial elements of functioning (Leadership, Communication, Roles and Procedures, and Input Interaction) work together to affect collaborative functioning positively, negatively or both. Three possible outputs are offered by the model: additive results, synergy and antagony. Additive results by-pass the collaborative context all together – the partners accomplish what they would have done without the partnership and no more (2 + 2 = 4). Synergy is the intended outcome of collaborative work – the interaction of inputs and throughputs lead to a result greater than what would have been accomplished otherwise (2 + 2 = 5). Antagony is a negative result where the process of working in collaboration actually drains resources (2 + 2 = 3).

The Model denotes interaction at every stage of the collaborative process. The inputs interact with one another, negative and positive functioning affects future functioning by creating cycles of interaction, output from the partnership feedback into the collaboration impacting functioning either positively or negatively thus, in turn, impacts the collaboration's ability to recruit additional inputs.

The case

KIWAKKUKI, an abbreviation of the Swahili name translated as ‘Women against HIV/AIDS in Kilimanjaro,’ is a grassroots organization with over 6,000 members. It is one of a faction of NGOs comprised of community members who band together to provide ‘self-help from below’ service provision to fill the gap in social services left in many African countries in the wake of structural adjustment programs Citation12 Citation30. Structural adjustment policies were introduced in Africa in the 1980s and 1990s by the World Bank and International Monetary Fund to redirect the State money from other areas of the national budget toward international debt repayment Citation31. In the absence of state provided social services, NGOs have stepped in to provide services for everything from health education to hospital care Citation32.

Grassroots volunteers carry out most of KIWAKKUKI's activities in local communities throughout the region. Each grassroots group is comprised of at least 20 women who volunteer to help those in their community who are infected or affected by HIV or AIDS. Some examples of the field activity of KIWAKKUKI can be found in the most recent Annual Report of KIWAKKUKI from 2009 Citation33. KIWAKKUKI worked to debunk myths about HIV transmission and prevention and to encourage testing, creating awareness among youth through both in-school and after school education initiatives. KIWAKKUKI provided voluntary testing and counseling for over 5,000 people both institution-based and mobile testing centers. Children were supported through KIWAKKUKI to attend primary, secondary and vocational training. Young people were also supported through psychosocial counseling, legal support (birth registration, inheritance and succession planning) and memory book projects. In total 400 children were served in 2009. KIWAKKUKI supported more than 3,500 male and female AIDS patients through home-based care initiatives, providing monitoring, medication and referral services. The year 2009 also saw the establishment of Village Community Banks among youth, caregivers and people living with HIV to help address overall household poverty.

These activities are all supported to a greater or lesser extent through partnerships with Northern organizations Citation19. Since their inception as an NGO in 1995, KIWAKKUKI has collaborated with organizations such as: universities, private philanthropic foundations, national development agencies, international non-governmental organizations, non-governmental organizations, and services clubs. Many of these relationships have lasted over a decade. In 2009 when the last data was collected, Northern donors provided about 90% of KIWAKKUKI's funding, with membership fees and income-generating activities providing the remaining 10%. Corbin et al. Citation19 notes, however, that in-kind contributions of money and materials from grassroots volunteer members and KIWAKKUKI staff may not be adequately reflected in the ‘10 percent’ figure – it may have a much greater impact than the numbers indicate. The significant majority of these funds are connected to specific projects (19).

Study aim

The overall purpose of this study was to examine KIWAKKUKI's experience as the Southern partner in many successful NSPs. We sought to understand their success in terms of why they have been sought after by Northern organizations to participate in NSP and what the consequences of that success have been. The specific aim was to explore the interactive processes of growth over time within NSP. We asked the question: what does applying the Bergen Model of Collaborative Functioning to the analysis of NSP reveal about the elements and processes at work through the experience of scaling up?

Methods

A qualitative case study was undertaken to examine the interactive processes at work within NSP through the in-depth analysis of KIWAKKUKI and their NSPs over their 20 years history. According to Yin Citation34, a case study design allows a researcher to examine complex social phenomena within its natural context, enabling rich analysis which retains holistic and meaningful characteristics of real-life processes. Qualitative research can aid in the understanding of the nuances of partnership functioning that quantitative research has no way to measure Citation35.

The data presented here were collected from a combination of participant observation, face-to-face or group interviews and primary and secondary document analysis. The data were obtained during two field visits to Moshi in 2008 and 2009.

Documents examined included annual reports, project proposals, communications with Northern partners, internal reporting, financial documents and promotional materials and secondary documents produced by external evaluators. Observational data included in the analysis consisted of the first author's field log of direct observations of interactions within the local environment, daily activities of work, meetings, interacting with beneficiaries and hosting Northern visitors.

A total of 18 individuals were interviewed. Nine participants were interviewed on the first field visits. These were purposively selected for their experience working with Northern partners (eight were current staff and one was a long-term voluntary member). A narrative interview approach was used and participants were asked open-ended questions to elicit stories of their experience with NSP and the historical development of KIWAKKUKI Citation36. Each interview began with a description of the study's purpose.Footnote1 The content, direction and subject matter discussed varied considerably from interview to interview depending upon the person's role in the organization.

The majority of these interviews were one-on-one with the first author (or the first and third authors). One was a group interview with four staff members and the first and third authors. All the interviews were conducted by the first author in English. The second round of interviews, conducted in 2009, included three new interviews with respondents previously interviewed in 2008 and interviews with nine new participants. The purpose of the second round of interviews was to get a general history of the development of the organization and its partnerships. The second group of participants included all the available ‘founding mothers’, current and former staff members, as well as long-time volunteers, community recipients, and board members. The interviews lasted from 10 ms to several hours, with the majority of interviews lasting 1 hour. One interview with a community recipient was conducted in Swahili with a KIWAKKUKI staff member translating; all other interviews were conducted in English by the first author.

The data presented in this paper came from both sets of data. The analysis of the data was an ongoing and iterative process beginning at data collection and continuing through reporting Citation37. The analytical process consisted of several phases, including managing the data, reading and note-taking, describing, classifying and interpreting and representing it Citation38. The data were examined for emerging themes and categorized accordingly. The data were also examined against the BMCF framework to identify inputs, collaborative processes and outputs; and according to Uvin's typology of scaling up. The results are presented to answer the main research question: What does applying the Bergen Model of Collaborative Functioning to the analysis of NSPs reveal about the elements and processes at work through the experience of scaling up?Footnote2

This study is one in a series of studies of KIWAKKUKI undertaken by the authors. From study to study, the interview data were used selectively depending on the research question in focus. The present study depended on data from the sub-set of respondents (n=6) who had knowledge of the entire process of scaling-up over the 20-year history; the ‘founding mothers’, long-time volunteers/staff and recipients. Data from respondents whose time with KIWAKKUKI was relatively short are not used in this study, even if they have been used in other studies in the series.

Results

We first present evidence from document data that describes KIWAKKUKI's scaling-up activities. We then present data according to the categories of the BMCF that emerged during the narrative interviews. To reflect the retrospective nature of the stories we were told by respondents, we start with a discussion of the early synergy that was experienced, and then trace the subsequent impacts of synergy on collaborative functioning, including KIWAKKUKI's experience of negative cycles of interaction and antagony that followed from their growth.

Scaling-up

KIWAKKUKI (Kikundi cha Wanawake Kilimanjaro Kupambana na UKIMWI) or Women Against AIDS in Kilimanjaro, was formed in 1990 in response to World AIDS Day which had the focus that year of ‘Women and AIDS’ Citation39. Achieving NGO status in 1995, they began their work by providing information and education to prevent the spread of HIV and reduce stigma. KIWAKKUKI wanted to ‘reach out to more women and let them be warriors… against AIDS (39).’ As their organization developed, they began working in collaboration with many Northern partners, to provide services across the continuum of HIV and AIDS experience: prevention and education for those not infected; voluntary counseling and testing for those wishing to know their sero-status; support groups for people living with HIV and AIDS (PLHA); home-based care for the sick; and material and psycho-social support for children orphaned by HIV/AIDS Citation40. KIWAKKUKI formed its first official partnership with a Northern organization in 1998 and had grown to 15 active partnerships with Northern organizations at the time of data collection.

Through its partnerships with Northern organizations, and also on its own initiative, KIWAKKUKI has engaged in many forms of organizational development. Northern partners routinely provide capacity building training and workshops for staff on report and proposal writing. They have also contracted with an independent organization to conduct an Organizational Development Intervention that led to KIWAKKUKI drafting and implementing their first Strategic Plan.

Output: synergy

Several years ago KIWAKKUKI reached such a level of success in their work that they stopped having to go out blindly looking for funding partnerships with Northern organizations – potential partners now come to them to ask them to write proposals. When asked in the group interview why these organizations were so keen to partner with KIWAKKUKI, participants gave several answers, citing various Maintenance activities, such as:Proposal writing:

To me, I think one of the big reasons is the way we write our proposal – we say “We want to train 10 home based care providers who are at the grassroots.”

Rigorous book-keeping practices:

We do (work) according to the activities that we planned. And we do not misuse the fund by doing other business or by lying to a donor that we have already trained while we didn't do that.

Reporting:

And I think also reporting. The way we report. And when they come for evaluation, they meet what we reported. Like maybe we reported that (a recipient) is receiving income generating activities so when they come they found (the recipient) is having some livestock, and she meets all the criteria which are needed – so that I think that gives the donors hope of continuing to supporting us.

While someone else added:

And also we meet the deadline of reporting.

Other participants described KIWAKKUKI's attention to Production activities:

I think to me that is the big achievement of KIWAKKUKI because we are focusing directly to the implementation which we had planned and we focus to the beneficiaries we planned to the activities.

Another spoke of how having successful projects, which produce Synergy, lead to more respect and therefore greater success:

It is also because the work we are doing is recognised by everybody in the community. And they give testimonials to support our work.

Partner resources were also identified as being crucial to the creation of Synergy. One of the founding mothers immediately identified their voluntary grassroots base as being attractive to Northern partners.

Through this voluntarism, most of the international donors – were more interested to work with us. Because they knew most of the things would be done voluntarily – if you give a little bit of money to enable. I don't know any other organization which has been voluntary and such a success like KIWAKKUKI.

The strong voluntary grassroots base was not only attractive to Northern partners; it also drove further growth within the grassroots. As KIWAKKUKI began to develop programs and projects, community groups from villages all over the region wanted to become a part of the work. The voluntary membership base expanded very rapidly.

People are joining, are really coming automatically. Not asking for anything. They just say ‘yeah, I want to be a member.

Output affects throughput

Leadership

In 2003, as a result of an organizational development intervention (a form of capacity building, sponsored by one of KIWAKKUKI's Northern partners), KIWAKKUKI decided to decentralize their activities to the district level. This decentralization led to a rapid expansion of grassroots groups.

Decentralization… was a step forward, but also new challenges emerged because we were encouraging the district coordinators to open more grassroots groups. Because in the past we had about 10 grassroots groups and then the number went up to 30. But when we decentralized the number went up drastically to more than 100.

Maintenance and production tasks

This fast growth caused a major shift in the way KIWAKKUKI operated. In the early stages of KIWAKKUKI's development, grassroots groups were given extensive training to learn about the organization, its programs as well as to learn skills for service delivery.

We got money from donors to train the women. And we trained them how to run their own group on their own in the locality where they are… We would train them for ten days about AIDS, about small projects – income projects, about orphans, and also about their own health. But mostly, the first thing would be about KIWAKKUKI. To understand KIWAKKUKI. So – after these ten days training – then we would call it ‘a KIWAKKUKI-trained group’. So they run their own activities. They do the membership enrolment. They'll increase the membership… They all knew: what is KIWAKKUKI, and why they are there, and what they are supposed to do, and especially about voluntarism.

Input interaction: funding, partner resources and mission

Eventually the rate of expansion exceeded the resources available for training, KIWAKKUKI encountered challenges to provide basic capacity building for grassroots volunteers.

The trouble came when the [membership] numbers mushroomed and the money [for training] coming from [Northern donor] was, like, negligible.

Only one Northern donor was a consistent supporter of KIWAKKUKI's grassroots training initiatives. One study participant explains that this donor was particularly motivated to contribute to these efforts because it aligned with that organization's strategic mission.

This is a group, [Northern Partner] who would like to see women taking a lead, and this is what [Northern partner] would like to see – a feminist movement, so that's why they have always supported us, and usually they would say in the proposal ‘tell us what you want to do’ and we have always put grassroots capacity building in the proposal.

The majority of KIWAKKUKI's other Northern partners have not been interested in providing funding for the training of grassroots groups. They are willing to provide funding for programs and projects but capacity building for volunteers from the grassroots is not their priority.

So you see these are the policies. [Northern partner] is [funding] research. They haven't got money unless they edit proposal, which is based on research. So it is not their interest [to fund training]. So it's all [partner mentioned above] putting funding into this. But then there is also a limitation in the amount of money they can give us.

Cycles of negative functioning and antagony

This lack of training of grassroots volunteers is perceived to be a weakness.

The problem now is that most of the groups are not trained. So they are formed but not trained and this is now what we are trying to ask the people to – before a group is being registered – they have to be trained. They have to understand what is KIWAKKUKI. Where and why KIWAKKUKI was formed. Once people would understand that, then the work will be easy. Because KIWAKKUKI is not there for giving work or for looking for a job or something. KIWAKKUKI is there for the community.

One ‘Founding Mother’ remarked that this lack of training, coupled with the influx of funding and, therefore, job opportunities – have led to an erosion of understanding of the goals and objectives of KIWAKKUKI and has led to a loss of the spirit of voluntarism among the grassroots.

We lost the track of voluntarism. (First), we forgot – not forgot – we came in to KIWAKKUKI for a job to earn money and the voluntarism started to thin out. Second, the groups who were formed in a – when we were forming KIWAKKUKI we were trying to see that you don't form too many groups at one time. You form one, you train. Then you go to the next. And then you go to the next and you train. You go to the next. These are now – the groups were just forming. And there are too many. So now the work now is to go back and train.

These negative processes demonstrate that a paradox exists in that Northern partners are drawn to KIWAKKUKI for their vast network of grassroots volunteers but that those same partners have failed to fund the development needed to maintain that network's vitality.

They give us money because we are community based, but the contradiction is that we do not get [money to maintain our community base].

Discussion

The results presented here give an historical account of the scaling-up process KIWAKKUKI experienced within their NSP relationships. Examining this account using the BMCF (19), two unique findings can be gleaned from this analysis. The first is practical and has to do with connecting the missions of Northern and Southern organizations. The second has to do with the process of scaling up and the unintended consequences of growth through NSPs.

Disconnected missions

Some of the findings here echo findings of other researchers. For instance, Harris’ (16) finding that while Northern partners express an interest in developing community participation, they rarely allow time for it, is closely linked to the case's experience of being selected by Northern partners for having a large grassroots base but then not providing the appropriate resources to maintain that community volunteer base. KIWAKKUKI's need for grassroots training could also be considered a Southern need being overlooked in favor of Northern agendas (16). The unique contribution of this study is that employing the BMCF allows observations to be made that go deeper than discounting such practices as strict ‘Northern domination.’ By examining the elements of partnership through the BMCF frame, nuances emerge which enable the problems of individual collaborations to be highlighted and worked-on which may be more productive than generalizing such problems to the wholesale concept of NSP.

In NSPs, there is at least one Northern organization and one Southern organization. The missions of the individual organizations determine not only the mission of the particular partnership and its projects but also how work is actually done. As described above, the only Northern organization that gave substantial resources for developing the grassroots was also the only organization that had grassroots capacity building as one of its own mandates. While the participants from our case perceived Northern partners to value grassroots participation, they observed that Northern organizations that did not explicitly have grassroots training as central to their own mission did not support them in maintaining them.

One consideration raised by the examination of data using the BMCF is that communication may be part of the problem. As described in the case section, KIWAKKUKI has numerous Northern partners from many countries. Coordination between diverse partners can complicate and increase burdens in NSP maintenance processes (19). Harrison (6) and Mommers et al. (9) described accountability and communication as a one-way street. Perhaps, KIWAKKUKI's need for training is being overlooked by their Northern partners because they lack the communication channels to describe their need.

Growth: too much of a good thing?

Using Uvin's (10) typology, one can see how KIWAKKUKI has scaled up along each of his four categories. In the period from 1992–2007, KIWAKKUKI experienced a quantitative scaling in its membership base from 42 members to over 6,000 – drastically increasing the organization's size and geographic reach within the Kilimanjaro region. Having begun with education as the primary focus, KIWAKKUKI has undergone a functional scaling up, including voluntary counseling and testing (VCT), support for adults and children living with HIV and AIDS into core activities. KIWAKKUKI also engaged in political scaling up by reaching beyond service delivery programs to work on advocacy and policy initiatives. Finally, KIWAKKUKI has undertaken organizational scaling up by availing itself of training and engaging other resources to build capacity at the organizational level, as described above.

Some of the challenges described in the literature such as losing connection to the grassroots and community-needs, and over-emphasis on professionalization (10, 22, 23) are hinted at in the findings here. However, this study from the perspective of a Southern organization is valuable as it clearly demonstrates KIWAKKUKI's challenges are not a loss of focus on the part of the Southern partner but a failure in the partnership to adequately address capacity building.

KIWAKKUKI's experience with growth furthers the academic understanding of partnership functioning by illustrating a scenario where synergy (success resulting in this case from growth) has a negative impact. Heretofore, synergy has been characterized as a strictly positive concept within the BMCF (24, 26–29). Synergy is described as the result of high quality and sufficient inputs combining under adept leadership, defined roles/procedures and effective communication. These positive results were then observed to feed back into the collaboration in positive ways (e.g. improving motivation and recruiting more resources). The lesson of KIWAKKUKI's experience with its rapid expansion of its grassroots groups is that the production of synergy also has the potential to impact that partnership negatively. KIWAKKUKI was having much success in their programs. However, this success came too quickly. There was not enough time and capacity for all levels of the organization, especially the grassroots base, to grow at the same rate as the rest of the organization. So the synergy that KIWAKKUKI experienced had clear unintended negative consequences.

Lewis (12) also notes this possibility of unintended consequences of rapid growth in individual NGOs. It is possible that this is exacerbated by the disconnectedness of scaling-up processes in the context of NSP. For instance, many different Northern partners were contributing to the growth of KIWAKKUKI. Perhaps it would be easier to coordinate and plan for the growth if it was all part of a single project or program. Because it was across several programs all at once it may have been more difficult to track.

The paradox: where are the people in ‘civil society’?

North-South partnerships have replaced older models of aid and development by giving hope that such a partnership would link Northern money and expertise with Southern know-how and community participation to create relevant health and development initiatives that local communities can take part in and benefit from.

We sought to understand a successful case of a Southern partner within NSPs both in terms of why they have been sought after by Northern organizations to participate in NSP and what the consequences of that success have been. Our data show that among other things Northern donors have been drawn to the case organization because of the strength of its grassroots structure. However, we also found that over the course of maturation and scaling-up, the maintenance and training of their community volunteers has been slowly eroded by a lack of alignment between the mission of the Southern partner and those of their Northern partners on the practice of grassroots capacity building. If the intention of North-South partnership and the ethic of community empowerment are to be realized, Northern organizations need to examine the paradox that exist between the rhetoric of grassroots community engagement and actual budget allocation. In short, ‘people’ must be prioritized in civil society engagement.

Further research might look into the impact of these processes on the actual delivery of services in the region and the impact such practices have on health outcomes. Future studies may also expand on this work by examining the Northern perspective simultaneously with the Southern perspective, or by engaging in participatory research with organizations involved in ongoing NSPs. At the outset of this study, we wished to engage KIWAKKUKI as partners in the project but they declined the invitation saying they were interested in hearing the findings but did not have an interest in formulating research questions, devising the inquiry strategy or in co-authorship.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the staff, volunteers and recipients of KIWAKKUKI who willingly gave their time, knowledge and energy to this project. We also would like to thank the anonymous reviewers whose insightful feedback greatly improved the final version of this paper. The research was funded by the University of Bergen.

Notes

1An example of such an introduction is: ‘In terms of the partnership project, what I am interested in is your individual experience with when partners from the North are involved in projects, provide expertise or whatever the partnership arrangement is. When it works well – how does it function? And what's the communication like? What roles do people play? Who are the leaders of the partnership? And how does the work get done? Can you tell me about your experience working with Northern partners?’

2The overall aim of the research was to use the Bergen Model of Collaborative Functioning to examine KIWAKKUKI as a case of mostly successful NSP. After the interviews were conducted, transcription and initial analysis revealed many themes emerging about growth processes related to success. Using the iterative qualitative process described by Creswell (Creswell, 2007), we formulated this specific question to guide a more defined analysis of the data.

References

- Uvin P, Jain PS, Brown LD. Think large and act small: toward a new paradigm for NGO scaling up. World Dev. 2000; 28: 1409–19. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.18369.

- Edwards M. NGO performance – what breeds success? New evidence from south Asia. World Dev. 1999; 27: 361–74. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.18369.

- Corbin JH, Tomm Bonde L. Intersections of context and HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: what can we learn from feminist theory?. Perspect Pub Health. 2012; 132: 8–9. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.18369.

- Brinkerhoff JM. Partnership for international development: rhetoric or results? Illustrated. ed. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers. 2002, 205.p.

- Fowler A. Introduction beyond partnership: getting real about NGO relationships in the aid system. IDS Bull. 2000; 31: 1–13. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.18369.

- Harrison E. The problem with the locals: partnership and participation in Ethiopia. Dev Change. 2002; 33: 587–610. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.18369.

- Bhatnagar B, Williams AC. Participatory development and the World Bank: potential directions for change. Report No. 183. World Bank Publications. Washington DC, 1992; 195.

- Clark J. Democratizing development: the role of voluntary organizations. Kumarian Press. West Hartford CT, 1991; 226.

- Mommers C, van Wessel M. Structures, values, and interaction in field-level partnerships: the case of UNHCR and NGOs. Dev Pract. 2009; 19: 160–72. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.18369.

- Uvin P. Scaling up the grass roots and scaling down the summit: the relations between Third World nongovernmental organisations and the United Nations. Third World Q. 1995; 16: 495–512. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.18369.

- Hoksbergen R. Building civil society through partnership: lessons from a case study of the christian reformed world relief committee. Dev Pract. 2005; 15: 16.10.3402/gha.v5i0.18369.

- Lewis D. The management of non-governmental development organizations2nd edn. Routledge. London, 2007; 305.

- Riddell R, Robinson M. The impact of NGO poverty alleviation projects: results of the case study evaluations. Report No. 68. Overseas Development Institute. London, 1992; 36.

- Sanders D, Stern R, Struthers P, Ngulube TJ, Onya H. What is needed for health promotion in Africa: band-aid, live aid or real change?. Crit Pub Health. 2008; 18: 509–19. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.18369.

- Brehm VM. Autonomy or dependence? Case studies of north-south NGO partnerships. INTRAC. Oxford, 2004; 207.

- Harris V. Mediators or partners? Practitioner perspectives on partnership. Dev Pract. 2008; 18: 701–12. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.18369.

- Lister S. Power in partnership? An analysis of an NGO's relationships with its partners. J Int Dev. 2000; 12: 227–39. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.18369.

- Mawdsley E, Townsend JG, Porter G. Trust, accountability, and face-to-face interaction in North–South NGO-relations. Dev in Pract. 2005; 15: 77–82. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.18369.

- Corbin JH, Mittelmark MB, Lie GT. Mapping synergy and antagony in North-South partnerships for health: a case study of the Tanzanian women's NGO KIWAKKUKI. Health Promot Int. ; 2011. Available from: http://heapro.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2011/12/15/heapro.dar092.abstract [cited 23 January 2012]..

- Ashman D. Strengthening north-south partnerships for sustainable development. Nonprofit Voluntary Sect Q. 2001; 30: 74–98. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.18369.

- Ebrahim A. NGOs and organizational change: discourse, reporting, and learning1st edn. Cambridge University Press; , 192 p. Cambridge, 2005

- Constantino-David K. The Philippine experience in scaling-up. Making a difference: NGOs and development in a changing world. Edwards M, Hulme DEarthscan Publications. London, 1992; 137–8.

- Fowler A. Building partnerships between northern and southern development NGOs: issues for the 1990s. Dev Pract. 1991; 1: 5–18. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.18369.

- Corbin JH, Mittelmark MB. Partnership lessons from the global programme of health promotion effectiveness: a case study. Health Promot Int. 2008; 23: 365–71. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.18369.

- Wandersman A, Goodman RM, Butterfoss FD. Understanding coalitions and how they operate as organizations. Community organizing and community building for health2nd ed. Minkler MRutgers University Press. New Brunswick NJ, 1997; 261–77.

- Endresen EM. A case study of NGO collaboration in the Norwegian alcohol policy arena. ; 2007. Available from: https://bora.uib.no/handle/1956/4466 [cited 25 February 2011].

- Corwin L, Corbin JH, Mittelmark MB. Producing synergy in collaborations: A successful hospital innovation. The Innovation Journal: The Public Sector Innovation Journal. 2012; 17(1): article 5. Available from: http://www.innovation.cc/scholarly-style/lise_corwin_v17i1a5.pdf [cited 13 June 2012].

- Dosbayeva K. Donor-NGO collaboration functioning: case study of Kazakhstani NGO. ; 2010. Available from: https://bora.uib.no/handle/1956/4450[cited25February2011]..

- Kamau AN. Documentation of the implementation strategy. A case study for the Kibwezi community-based health management information system project, Kenya. ; 2010. Available from: https://bora.uib.no/handle/1956/4276 [cited 25 February 2011]..

- Robinson M, White G. The role of civic organizations in the provision of social services. Report No. 37.. Helsinki: United Nations University/World Institute for Development and Economics Research. 1997, 64. p.

- Corbin JH. Health for All by the year 2000: a retrospective look at the ambitious public health initiative. Promot Educ. 2005; 12: 77–81.

- Edwards M, Hulme D. NGO performance and accountability: introduction and overview. NGOs performance and accountability: beyond the magic bullet. Edwards M, Hulme DEarthscan Publications. London, 1995; 3–16.

- Itemba D. KIWAKKUKI 2009 Annual Report. Moshi. , Tanzania: KIWAKKUKI. 2009. 20. p. Available from: http://kiwakkuki.org/?file_id = 1 [cited 2 May 2012]..

- Yin RK. Case study research: design and methods3rd ed. Sage Publications; , 200 p. Thousand Oaks CA, 2009

- El Ansari W, Weiss ES. Quality of research on community partnerships: developing the evidence base. Health Educ Res. 2006; 21: 175–80. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.18369.

- Kvale S, Brinkmann S. Interviews: learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing2nd edn. Sage Publications; , 367 p. Thousand Oaks CA, 2008

- Silverman PD. Doing qualitative research2nd ed. Sage Publications. Thousand Oaks CA, 2004; 416.

- Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. Sage Publications; , 424 p. Thousand Oaks CA, 2007

- Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. Sage Publications. Thousand Oaks CA, 2007; 424.

- Lie GT, Lothe EA. KIWAKKUKI: women against AIDS in Kilimanjaro Region, Tanzania: a qualitative evaluation. Oslo: Kvinnefronten/Women's Front of Norway. 2002; 67.