Abstract

Following the second Sahelian famine in 1984–1985, major investments were made to establish Early Warning Systems. These systems help to ensure that timely warnings and vulnerability information are available to decision makers to anticipate and avert food crises. In the recent crisis in the Horn of Africa, alarming levels of acute malnutrition were documented from March 2010, and by August 2010, an impending food crisis was forecast. Despite these measures, the situation remained unrecognised, and further deteriorated causing malnutrition levels to grow in severity and scope. By the time the United Nations officially declared famine on 20 July 2011, and the humanitarian community sluggishly went into response mode, levels of malnutrition and mortality exceeded catastrophic levels. At this time, an estimated 11 million people were in desperate and immediate need for food. With warnings of food crises in the Sahel, South Sudan, and forecast of the drought returning to the Horn, there is an immediate need to institutionalize change in the health response during humanitarian emergencies. Early warning systems are only effective if they trigger an early response.

On July 21st, 2011, the New York Times headlined ‘Food crisis in Somalia is a famine, U.N. says’. It was the first famine declared since 1991–1992 and first significant food crisis in three years. By the time the major global press began to document the food crisis in the Horn of Africa (HOA), however, it was already much too late. Malnutrition and hunger were already widespread in the region affecting over 10 million people and communities had started migrating in search of food.

In 1984–1985, severe famines in Sudan and Ethiopia prompted the international community to put in place Early Warning Systems (EWS) to anticipate and avert future food crises. The Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), for example, has been in place since the mid-eighties to ensure that timely and rigorous early warning and vulnerability information are available. USAID budgeted $23 million in 2011 for FEWS NET so that policy makers could readily identify potential threats to food security. Large investments have also been made in other EWS such as the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)'s Global Information and Early Warning System and World Food Programme's Vulnerability Analysis and Mapping Unit, to name just a few.

The ultimate goal of these EWS is to provide decision makers with up-to-date information necessary to avert or mitigate the impact of a food security hazard. FEWS NET utilizes the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) as a standardized scale to assess the food security, nutrition and livelihood information to classify the severity of acute food insecurity outcomes. Acute malnutrition is categorized by the prevalence of global acute malnutrition (GAM) and severe acute malnutrition. Under IPC, GAM prevalence between 15–30% is considered a Phase 4 of an ‘emergency’ while prevalence exceeding 30% is a Phase 5 of a ‘catastrophe’ or a ‘famine’ Citation1. At Phase 4 levels, the international humanitarian system is triggered into full response mode.

Overall, several of the functioning EWS performed their task effectively during the recent HOA crisis. As far back as March 2010, surveys began documenting critical rates of acute malnutrition and assessing the overall nutrition status as being critical or very critical across all urban centers scattered throughout the country Citation2. By August 2010, there was concern about severe food insecurity developing in east Africa and an impending crisis was forecast. In March 2011, additional warnings were issued on the alarming situation which was expected to deteriorate further. By mid-2011 when famine was finally declared, surveys conducted in the crisis-affected regions of southern Somalia showed that 13 of 18 locations had GAM levels exceeding 30% and all 18 locations had Crude Mortality Rates that exceeded the emergency threshold of 1/10,000 a day. These figures not only surpassed the IPC Phase 4 levels, they also exceeded the IPC Phase 5 or catastrophe or famine level. By this time, FAO estimated that 11 million people were in desperate and immediate need for food Citation3.

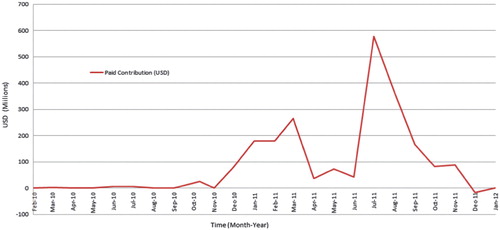

Despite the wide availability of up-to-date information on the deteriorating conditions in late 2010, humanitarian aid was both sporadic and inadequate. The small increase in aid in early 2011 did little to avert the crisis that unfolded shortly after (). There was a surge in aid only when the UN declared famine and media increased their level of coverage of the HOA crisis.

The fact that the response to the east African famine was delayed and inadequate did not go unnoticed Citation4 Citation5.

In light of the suffering afflicted by the drought and delay in response, organizations around the world drafted the Charter to End Extreme Hunger, to seek government commitment to take the steps to prevent suffering of this scale from reoccurring Citation6. The Ministers of International Development of Norway, United Kingdom, and the European Commission all declared their support for the Charter. The non-governmental sector also decried the delayed response and called for change Citation7.

Unfortunately, the HOA is not the only region today where early warnings did not trigger an early response. In South Sudan, 4.7 million people are expected to be food insecure during 2012 and conditions are deteriorating daily Citation8. An estimated 10 million people are also facing food insecurity and over 1 million children are at risk of severe acute malnutrition in the Sahel countries. Facing a serious food and nutrition crisis, Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger have declared a crisis and called for international assistance. Exacerbated by the conflict-induced displacement in Mali, conditions in the region are worsening and immediate emergency assistance is required to prevent further increases in the rates of malnutrition Citation9 Citation10.

Admittedly, it is difficult to justify and mobilize the humanitarian resources when a situation has not reached critical levels. Yet, if alarms are only sounded when children and other vulnerable populations are already suffering from acute malnutrition and mortality is increasing, the response – however rapid – will be too late.

With the deteriorating food crises in the whole Sahel region and South Sudan, there is an urgent need to institutionalize change now.

First, the mechanisms that guide the release of humanitarian funds must be reviewed and modified. Currently, appeals are based on what is programmatically achievable given constraints of access and partners, rather than what is required to avert disasters. The delay in response was further compounded by the UN humanitarian appeal timeline which did not align with the seasons in the HOA. In September 2010 assessments were carried out before October, when rainy season usually begins. In turn, the assessment failed to take into account the failure of rains and also ignored the predictions of future weather patterns. A further weakness in early assessments is the potential and bias in responders conducting their own evaluations. Given the delay mobilizing funds and getting functional operation on the ground, the Central Emergency Revolving Fund (CERF) is a useful tool to jump start response in acute emergencies. Greater reliance on independent and rigorous needs assessment could significantly strengthen the appropriate use of funds from CERF. It also needs to be better linked to early warning system.

Second, there is a need to operationalize trigger mechanisms. Certainly, the establishment of standardized triggers and corresponding thresholds may not always work; it is, however, an important step that must be taken to press for early response. Given its mandate to coordinate humanitarian actors in emergency responses and recent support of the Charter, the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) is well-placed to take leadership in these two initiatives. Member states should put in place the required conditions to allow such coordination. The capacity of OCHA to coordinate has been often questioned but not the pertinent need for a multi-lateral coordinating body. In-depth reform of OCHA to strength its credibility, independence and performance is clearly needed and this key humanitarian function should be given priority.

In conclusion, timely and effective prevention have been shown to save lives and money Citation11. By waiting for a situation to develop into a crisis, like the one in the HOA, children develop severe malnutrition that permanently affect their lives and the stage is set for disease outbreaks, hikes in mortality rates, social tensions, migration and conflicts. Beyond these concerns, there is, most importantly, a moral and ethical imperative for the humanitarian community to act. We must not wait for a situation to become a catastrophe; early warnings must trigger early response.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study.

References

- U.S. Agency for International Development and FEWS NET. IPC Acute Food Insecurity Reference Table for Household Groups [Internet]. Available from: http://www.fews.net/ml/en/info/pages/scale.aspx [cited 23 Mar 2012].

- Food Security and Nutrition Analysis Unit of Somalia. Nutrition Update: March-April 2010 [Internet]. [Updated 10 May 2010]. Available from: http://www.fsnau.org/downloads/Nutrition%20Update%20-%20March-April%202010.pdf [cited 23 Mar 2012].

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Rome emergency meeting rallies to aid Horn of Africa [Internet]. [Updated 25 July 2011]. Available from: http://www.fao.org/news/story/en/item/82543/icode/ [cited 25 Mar 2012].

- Guha-Sapir D, Heudtlass PL. Send food to Somalia – answer questions later [Internet]. Financial Times. 26 July 2011. Available from: http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/dce0bb0c-b709-11e0-974c-00144feabdc0.html#axzz1qsTkZnmG [cited 24 Mar 2012]..

- Lowenberg S. Global food crisis takes heavy toll on east Africa. Lancet. 2011; 378: 17–8. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.18481.

- Charter to End Extreme Hunger [Internet]. Available from: http://hungercharter.org/ [cited 10 Mar 2012].

- Hillier D, Dempsey B. A dangerous delay: the cost of late response to early warnings in the 2011 drought in the Horn of Africa. OxfordUK: Oxfam and Save the Children. 2012. p. 34.

- Ahmed S, Samkange S. Special Report: FAO/WFP Crop and Food Security Assessment Mission to South Sudan [Internet]. RomeItaly: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and World Food Programme. 2012. p. 58. Available from: http://www.fao.org/docrep/015/al984e/al984e00.pdf [cited 14 Mar 2011]..

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Emergency response appeal for Mali situation 2012 [Internet]. [Updated February 2012]. Available from: http://www.unhcr.org/4f463e659.pdf [cited 28 Mar 2012].

- FEWS NET. West Africa Food Security Alert: Sahelian food security Crisis to peak between July and September [Internet]. [updated 27 March 2012]. Available from: http://www.fews.net/docs/Publications/Alert_West_2012_03_en.pdf [cited 28 Mar 2012].

- The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Natural hazards, UnNatural disasters: the economics of effective prevention. WashingtonDC: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. 2010, p. 50.

- Financial Tracking Services [Internet]. Available from: http://fts.unocha.org/pageloader.aspx?page = search-reporting_display&showDetails = &CQ = cq090312150914gaMlaOfsXX [cited 9 Mar 2012]..