Abstract

Introduction : Action is urgently needed to curb the rising rates of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and reduce the resulting social and economic burdens. There is global evidence about the most cost-effective interventions for addressing the main NCD risk factors such as tobacco use, unhealthy diets, physical inactivity, and alcohol misuse. However, it is unknown how much research is focused on informing the local adoption and implementation of these interventions.

Objective : To assess the degree of research activity on NCD priority interventions in LMICs by using bibliometric analysis to quantify the number of relevant peer-reviewed scientific publications.

Methods : A multidisciplinary, multi-lingual journal database was searched for articles on NCD priority interventions. The interventions examined emphasise population-wide, policy, regulation, and legislation approaches. The publication timeframe searched was the year 2000–2011. Of the 11,211 articles yielded, 525 met the inclusion criteria.

Results : Over the 12-year period, the number of articles published increased overall but differed substantially between regions: Latin America & Caribbean had the highest (127) and Middle East & North Africa had the lowest (11). Of the risk factor groups, ‘tobacco control’ led in publications, with ‘healthy diets and physical activity’ and ‘reducing harmful alcohol use’ in second and third place. Though half the publications had a first author from a high-income country institutional affiliation, developing country authorship had increased in recent years.

Conclusions : While rising global attention to NCDs has likely produced an increase in peer-reviewed publications on NCDs in LMICs, publication rates directly related to cost-effective interventions are still very low, suggesting either limited local research activity or limited opportunities for LMIC researchers to publish on these issues. More research is needed on high-priority interventions and research funders should re-examine if intervention research is enough of a funding priority.

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are a major cause of morbidity and mortality globally. In 2004, NCDs were responsible for 60% of all deaths and almost half of the burden of disease as measured in Disability-Adjusted Life-Years (DALYs) Citation1. The impact of NCDs extends beyond the world's wealthy, older populations. Eighty percentage of NCD deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) of which almost 30% are people under 60 years of age. Projections for 2020 indicate that Africa and other LMICs will have the largest increase in NCD mortality Citation1. The rise in NCDs is accompanied by a heavy economic impact. The estimated cumulative lost economic output for 2011–2025 caused by the four major NCDs in LMICs is more than US$7 trillion Citation2. This global NCD crisis threatens the achievement of both health and non-health development goals.

As evidenced by the United Nations (UN) High Level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of NCDs held in September 2011 Citation3 and the signing of the UN Political Declaration on the Prevention and Control of NCDs Citation4, policymakers in LMICs recognise the urgent need for action on NCDs. In low-resource settings, international experts are advocating for a focus on the evidence-based NCD strategies that have the greatest impact on health outcomes while still being very cost-effective and feasible Citation5 Citation6. Analysis on the cost of scaling up these priority interventions further supports their economic feasibility Citation7. Many of these identified priority interventions focus on primary prevention and recommend population-wide interventions that target the major NCD modifiable risk factors, that is, tobacco use, unhealthy diets, physical inactivity, and harmful use of alcohol.

Research is crucial to inform the development and implementation of these priority interventions in LMICs. Significant research has been done on the application of these interventions in high-income countries but contextual differences Citation8–Citation11 create limitations to how much this research can help inform work in LMICs Citation12–Citation14. While an assessment of research from these countries shows much NCD research activity despite the dominance of the infectious diseases research agenda Citation15, it is unknown how much NCD research in LMICs is focused on the strategies that stand to make the biggest impact on the NCD burden.

The purpose of this study was to assess the degree of research activity on NCD priority interventions in LMICs by using bibliometric analysis to quantify the number of relevant peer-reviewed scientific publications over a 12-year time period. This study provides evidence about the extent to which research efforts in LMICs are aligned with the need to support the adoption and implementation of NCD priority interventions in the world's poor countries.

Methods

Identifying priority interventions

For this study a ‘priority intervention’ is one that has been shown, based on the best scientific data available, to deliver large population health benefits at a relatively low cost. Population-wide interventions, many of which are based on the implementation of healthy public policies, legislation and regulation that reduce the main shared modifiable risk factors for NCDs Citation16, are a highly cost-effective approach to targeting NCDs Citation5 Citation7. While some individual-based treatment interventions have been identified as being high-impact and relatively cost-effective Citation5, this study focused on population-wide measures. This also excludes interventions that rely primarily on personal behaviour change through social marketing or individual counselling at the community or health care facility levels and publications focused on epidemiological evidence, surveillance, and biomedical science.

The selected interventions are grouped into three categories: tobacco control, healthy diets and physical activity, and reducing harmful alcohol use (). The priorities for tobacco control in LMICs are four key measures specified in the World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) that can prevent millions of deaths each year at a cost of less than US$1 per person per year: tobacco price increases, legislation of health warnings, smoking bans in both the work place and public places, and bans on tobacco advertising and promotion Citation17 Citation18. The category ‘healthy diets and physical activity’ encompasses approaches that promote healthy living by improving the dietary environment, for example, by undertaking salt reduction efforts Citation18–Citation22 and by modifying the built environment to facilitate active commuting through walking and cycling Citation23. Due to the anticipated low number of articles on physical activity priority interventions these articles were grouped with healthy diets to facilitate easier analysis and comparison across intervention types. The priority interventions to reduce harmful alcohol use are alcohol price increases through taxation, restricting the availability of retail alcohol, and implementing legislation to ban alcohol marketing and sponsorship Citation24.

Table 1. Non-communicable disease interventions identified as ‘priority interventions’ and examined in bibliometric analysis

Article search

The research articles included in this study were located through a systematic journal database search using 33 unique search strings that were developed for comprehensiveness and tested for relevance and scope. The names of the 144 LMICs on the World Bank's country classification list Citation25 were incorporated into the search string, along with generic terms used to refer to this group of countries or their regions (e.g. ‘developing country’, ‘low- and middle-income country’, ‘Sub-Saharan Africa’). The search strings were applied to the fields of Article Title, Abstract and Keywords for the document categories of Articles, Articles in Press, Reviews and Conference Papers in Scopus, a large multidisciplinary, multi-lingual research database with numerous open access publications Citation26. Though the search terms were English-language, all non-English records in Scopus have an English title and abstract Citation27 and thus were covered in the search. The searched time period encompassed the 12 years from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2011, and was conducted on February 13, 2012. The bibliographic records found were exported and combined in a single Microsoft Excel spreadsheet where duplicates were eliminated for a total of 11,211 unique articles. Excel was used for all data coding, data management, and analysis.

Coding

Using the title and abstract, each publication was assessed based on three inclusion criteria: one, a focus on the development, implementation or evaluation of one or more of the priority interventions; two, the research was set in one or more low- or middle-income country (LMIC); and three, the publication was a research article and not a news report, letter or editorial, etc. Publications could be based on primary or secondary research. A total of 525 articles met all three inclusion criteria and made up the data set. Using the bibliographic information (i.e. title, abstract, and authors’ institutional affiliations) and, if necessary, the full length article, each included article was reviewed and coded according to several dimensions (). Following a calibration exercise on a subset of articles, the coding criteria were refined and applied to the entire data set. Once completed, the coded data set was reviewed and checked for consistency. Of the 525 included publications, 72.9% [383] were articles, 22.6% [119] reviews, and 4.5% [24] conference papers. Approximately 86.3% [453] were published in English, 8.2% [43] Spanish, 2.5% [13] Portuguese, and 4.4% [23] were published in other languages (summed values are greater than 100% since some publications were available in multiple languages).

Table 2. Coding categories for included articles

Data analysis

Using Excel, the findings were tallied by year of publication, region of focus, type of the intervention by risk factor, first author's country, and first author type (LMIC author or HIC author). Sub-tallies were calculated for each year, region group, country, intervention category, first author's country, and author type. Frequencies, percentages, and cross tabulations were calculated. Graphical representations of the data were created in Excel.

Results

Article production by year

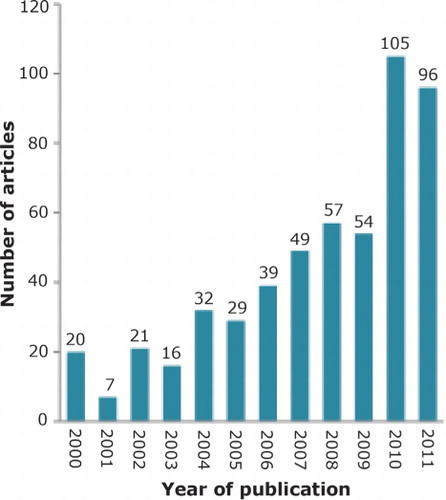

Among the 525 included articles there was a clear increase in the number of articles published each year on the topic of NCD priority interventions in LMICs (), increasing from 20 articles in 2000 to 96 articles in 2011 (a 480% growth). (It is expected that the number of 2011 articles will increase as more articles published in that year become available through electronic journal databases.) The growth was moderate for the first 10 years (a 270% increase from 2000 to 2009), with some fluctuation in yearly numbers. The year 2010 marked a substantial jump in publications (105 articles) with almost double the 2009 quantity, an increase that continued in 2011 with 96 publications. Of all identified articles on NCD priority interventions in LMICs, 38.3% were published in the last 2 years and nearly half (48.6%) in the past 3 years.

Regional comparisons

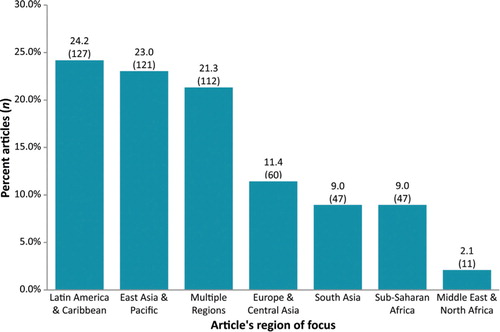

There is a substantial difference in the number of articles addressing each geographical region (). Three regional groups received the greatest focus: Latin America & Caribbean (127 articles, representing 24.2% of the total articles included), East Asia & Pacific (121 articles, 23.0%), and Multiple Regions (112 articles, 21.3%). Three regions had less than half as many articles: Europe & Central Asia (60 articles, 11.4%), South Asia (47 articles, 9.0%), and Sub-Saharan Africa (47 articles, 9.0%). LMICs in the Middle East & North Africa were the least frequently addressed in the target research articles (11 articles, 2.1%). When examining the distribution of articles according to each region's total population size, Latin America & Caribbean has the highest number of articles per capita, while Sub-Saharan Africa, Middle East & North Africa, and South Asia have the lowest number of articles per capita. Each region's peak yearly output has occurred in either 2010 (Latin America & Caribbean with 35 articles; East Asia & Pacific, 31; Multiple Regions, 21; Sub-Saharan Africa, 8; Europe & Central Asia, 14), or 2011 (South Asia, 12; Middle East & North Africa, 4), creating the escalation in articles for the years 2010 and 2011.

Fig. 2. Percent of articles set in a low- or middle-income country within a particular geographical region. Of the total number of included research articles, the percentage of them (and number) focusing on one or more low- or middle-income country within a particular geographical region. Articles focusing on more than one region are classified as ‘Multiple Regions.’

In every regional group except Middle East & North Africa, one or two countries dominate the focus of the publications. For East Asia & Pacific, almost half of the region's articles focus on China (60 of 121 articles), a recent increase that established East Asia & Pacific as the region with the highest number of articles for the year 2011. Thirty-four articles out of the 47 South Asia publications (72.3%) focus on India and for Europe & Central Asia, the Russian Federation leads (15 of 60 publications, 25%). Some countries’ regional dominance was consistent with their proportion of the region's population. For example, Mexico and Brazil were the topic of nearly half of the Latin America & Caribbean articles (63 of 127) and contain approximately half of the region's LMIC population. In other countries and regions, there is an imbalance. China has a smaller proportion of articles in comparison with their percentage of the region's population. South Africa is an opposite extreme; the country has less than 6% of Sub-Saharan Africa's population but almost 50% of the region's articles focus on South Africa (23 of 47). In each of these five regions, articles focusing on more than one country within the region (classified as ‘Multiple Countries’) ranked third or higher as the ‘country’ of focus for the region.

Comparisons of interventions by risk factor

Of the 525 articles, 365 (69.5%) addressed tobacco control interventions, 130 (24.9%) addressed healthy diets and physical activity (of which 16 covered physical activity) and 94 (18.0%) addressed reducing harmful alcohol use. (Values are non-cumulative since categories are not mutually exclusive.) Most of the articles focused on one intervention category (475 and 90.5%); 6.8% of articles (36 articles) focused on two risk factors; 2.7% (14 articles) focused on all three groups of risk factors. Approximately 86.8% (317 articles) of all tobacco control publications focused on only that topic, 72.3% [94] of healthy diets and physical activity addressed only that topic and 68.1% [64] of reducing harmful alcohol use. Among the tobacco control publications, the most common priority interventions were smoke-free spaces and tobacco taxes.

In the early stages of the examined time period, there was relatively little difference in the number of publications for each risk factor (), the growth of tobacco control publications quickly outpaced the other risk factors, undergoing a 1,014% increase from the year 2000 to 2011. Publications addressing priority healthy diet and physical activity interventions have grown steadily, with a 650% increase from 2000 to 2011. The yearly numbers of publications on alcohol priority interventions have risen and fallen. The top producing years for research publications on alcohol interventions were 2010 (17 articles), 2007 (13 articles), and 2000 (12 articles). In the year 2000, alcohol intervention was the highest number of articles out of the three intervention groups.

Table 3. Yearly articles for each intervention group as a percentage of total number of included articles

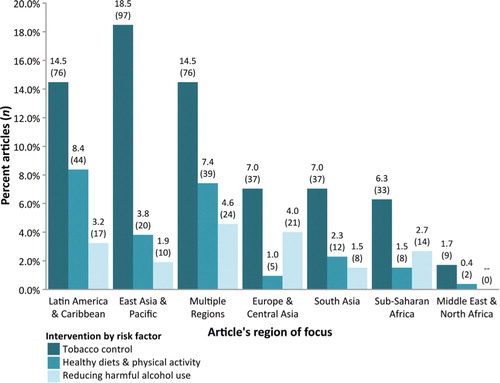

Tobacco control was the leading topic in all geographic regions (), with East Asia & Pacific as the region having the highest number of tobacco control articles (80.2% of the region's articles). Latin America & Caribbean tied with Multiple Regions for the second highest number of tobacco control intervention articles, but had the lowest percent of articles on tobacco control (59.8%). Healthy diets and physical activity articles ranked second place in five of seven regional groups (Latin America & Caribbean, East Asia & Pacific, Multiple Regions, South Asia, and Middle East & North Africa). Latin America & Caribbean had the highest number of articles addressing this topic and tied with Multiple Regions for highest percent of articles on this topic). Articles on reducing the harmful use of alcohol ranked second among the two regional groups (Europe & Central Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa). Thirty-five percentage of articles on Europe & Central Asia and 29.8% of articles on Sub-Saharan Africa addressed alcohol interventions. The regional group of Middle East & North Africa had no articles on priority interventions for reducing harmful alcohol use.

Fig. 3. Percent of articles on each intervention by risk factor for geographical regions. Of the total number of included research articles, the percentage of them (and number) addressing a non-communicable disease priority intervention. Interventions are grouped in three categories: tobacco control, healthy diets and physical activity, and reducing harmful alcohol use. Articles are organised by geographical region of focus. An article may be classified in more than one intervention type. Articles focusing on countries from more than one region are classified as ‘Multiple Regions.’

Authorship patterns

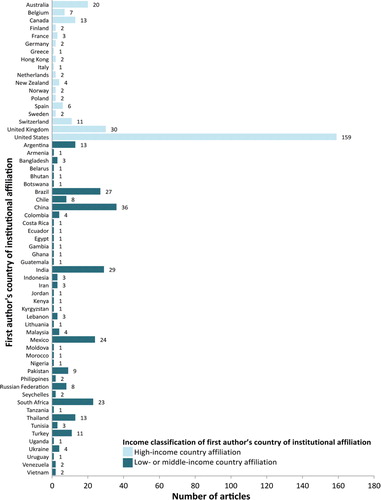

Of the 525 included articles, a large proportion had a first author whose institutional affiliation was with a high-income country (HIC) (51.2%, 269 articles); 48.8% of first authors (256 articles) provided an institutional affiliation in a LMIC (). The yearly output values indicate a trend in the past 3 years toward a higher proportion of ‘LMIC authors.’ This increase in LMIC authorship coincided with recent increased first authorship from researchers with institutions in China, Mexico, and India. In 2010 and 2011 authors from these three countries were first authors on 25.4% of all publications for those years.

Table 4. Yearly articles by country income classification for each article's first author country of institutional affiliation

The United States was overwhelmingly the most common country of institutional affiliation (). The five most frequently listed high-income countries for first author institutional affiliation were United States (30.3% of all articles), United Kingdom (5.7%), Australia (3.8%), Canada (2.5%), and Switzerland (2.1%). The 11 most frequently listed LMICs for first author institutional affiliation were China (6.9%), India (5.5%), Brazil (5.1%), Mexico (4.6%), South Africa (4.4%), Argentina (2.5%), Thailand (2.5%), Turkey (2.1%), Pakistan (1.7%), Chile (1.5%), and the Russian Federation (1.5%).

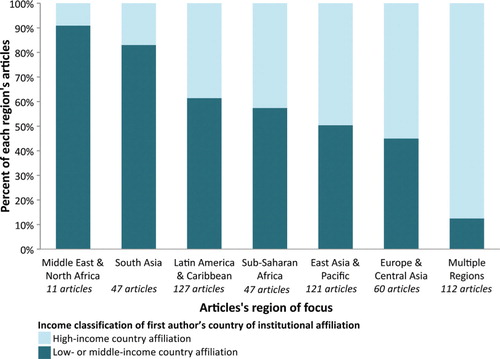

Authorship was examined for each regional group by comparing the proportion of LMIC authors to HIC authors in a region's publications (). Middle East & North Africa is the regional group with the highest percent of LMIC first authors (90.0%, nine of 11 articles). However, given the small number of articles from this region, it is possible that this difference could diminish with a larger sample. Articles addressing Multiple Regions had by far the lowest rate of LMIC authorship (12.5%; 14 of 112 articles). Articles focused on the regions of South Asia and Latin America & Caribbean had high LMIC authorship rates (83 and 61.4%) and contributed a large volume of LMIC authored papers. There was no difference in LMIC versus HIC authorship when articles were compared across intervention groups.

Fig. 4. Comparison of country income classification for first authors’ countries of institutional affiliation. For each geographical region of focus, a comparison of the percent of first authors who have an institutional affiliation in a low- or middle-income country versus the percent of first authors with a high-income country institutional affiliation. The number of articles associated with each region is listed.

Annexe 1. The number of included articles by first author's country of institutional affiliation. Articles are grouped by which country the first author's institutional affiliation lists. Countries are organised by income classification (high-income country affiliation or low- or middle-income country affiliation) and then alphabetically.

Discussion

This study found that there is still relatively little published research on NCD priority interventions in LMICs, with only 525 articles published in the last 12 years, a contribution that could be insufficient for influencing the local adoption and implementation of the interventions most promising for tackling the NCD epidemic. Other research has shown that a low publication level is a result of little activity on target interventions since publication outputs have been shown to follow the development and practice of interventions Citation28. In view of this, the scarcity of publications found in this study indicates that research activity on NCD priority interventions in LMICs is at a minimal level, especially in regards to NCD risk factors other than tobacco use. The current research focus on tobacco control priority interventions relative to healthy diets, physical activity, and alcohol reduction priority interventions may largely reflect the fact that the case for action is currently different for each specific risk factor. The FCTC laid out clear global tobacco control priorities and 175 countries have now signed and ratified the treaty Citation29. While the evidence base for priority interventions related to healthy diets, physical activity, and alcohol reduction is now rapidly expanding on a global scale, the level of political commitment and resources devoted to implementing them remain relatively low, especially in LMICs. Experts are exploring what lessons can be learned from tobacco control efforts that can be applied to address other NCD risk factors Citation30. There are calls, for example, to use an approach similar to tobacco with alcohol through a Framework Convention on Alcohol Control Citation31.

The possible underlying causes of the overall low level of research activity are multiple. Historically NCDs have been viewed as a problem limited to developed countries. This is a misconception which persists and continues to influence research agendas, government agendas, and funding opportunities as infectious diseases remain the focus of development efforts. Other health-related bibliometric analyses focusing on LMICs show greater levels of research intensity on HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis, global health challenges that are already firmly on the development agenda. For example, from 1998 to 2009 Indian scientists alone had published 2,786 articles on malaria research Citation32.

When NCD research is conducted, a high proportion of studies focus on epidemiology and surveillance and not on intervention research Citation33 Citation34. It may also be that NCD intervention research focuses on ‘non-priority’ interventions or interventions that target communities or special populations. For example, during our review of the over 11,000 articles yielded in our literature search, we observed a high number of publications addressing smoking cessation counselling or health education interventions for school-based populations. Though these types of approaches have a role in an integrated effort to reduce NCDs, current evidence indicates that in resource-constrained settings their implementation should not come at the expense of population-wide interventions Citation5. Though global efforts have been made to create a prioritised research agenda, the resulting outcomes have a seemingly inclusive approach to them, creating the chance that the true priorities may be lost Citation35 Citation36.

Within some countries and regions, capacity for developing and implementing an NCD intervention research agenda remains relatively limited and challenges in publishing peer-reviewed research persist. This study highlights that researchers from HIC institutions have a strong presence in NCD research conducted on LMICs. With the exception of tropical medicine Citation37, other branches of health research, including medicine Citation38, palliative care Citation39, and nutrition Citation40, have found similar results. In addition to the relative ‘newness’ of NCD prevention research, locally led research in LMICs is hindered by low numbers (per capita) of qualified public health researchers Citation41, poor access to research funding and challenges with the publication of research results Citation42, which includes limited capacity for writing articles for peer-reviewed journals Citation43, insufficient time to prepare manuscripts and possible manuscript selection bias Citation44 Citation45. Research topics of high-priority for LMIC researchers do not always appeal to journal editors who are catering to an audience of HIC researchers Citation42, as may be the experience of LMIC researchers from countries at earlier stages in the NCD epidemic who wish to publish research covering topics addressed in prior research in high-income countries.

Despite the overall low number of publications identified through this study, the increase in yearly outputs provides encouraging evidence that research activity on NCD priority interventions in LMICs has increased over the 12-year period examined. Furthermore, LMIC researcher leadership has increased both as a proportion of articles and in the number of publications, a growth that represents not only increased publishing but also local activity within LMICs on the development and implementation of evidence-based solutions. In our study as in other studies, LMIC authorship was highest in researchers from middle-income countries Citation46. However, considering that among the LMICs with a high proportion of NCD many are middle-income countries Citation47, this income group's high proportion of NCD intervention research may be appropriate and equitable.

During the examined time period there have been several major efforts to draw attention to NCDs Citation48–Citation53. The high number of articles published in 2010 and 2011 may be a result of the maturation of work initiated years earlier and it remains to be seen whether research on NCD priority interventions in LMICs will continue to increase and accelerate especially with the passing of the Political Declaration of the UN High Level Meeting on NCDs Citation4.

Limitations

The articles and data used in this study were limited by the results obtained through the use of a specific set of search terms at the time of searching the journal database Scopus. Though Scopus has a high number of non-English publications, there might be better databases that are more comprehensive for foreign language publications. Scopus does not provide information on the authors’ nationalities and since many researchers are based in countries different from their nationality and some researchers have multiple institutional affiliations, it cannot be assumed that the country of institution is the author's country of birth. We chose to focus on the first author's characteristics since first authorship represents research leadership; we did not examine the number of authors on each publication and co-authorship characteristics. This quantification of research articles is only a proxy for a measurement of research activity. It is possible that there is actually a substantial amount of research that has been conducted on NCD priority interventions in LMICs, but it is not being published or is published in sources not available through our Scopus searches. Since we could not track what article data was primary or secondary research, it may be that a large proportion of the articles we found are re-analysing the same data sets. If this is the case, our analysis overestimates the degree of NCD research activity.

The strength of this study lies in the comprehensive nature of the search strategy and specificity of the data coding. We reviewed over 11,000 articles to identify only those articles that met the inclusion criteria of informing a set of carefully-selected NCD priority interventions based in one or more of the 144 low- or middle-income countries. To our knowledge, this is the first study to use this method to conduct a bibliometric analysis on this topic. We believe that by using this approach, our findings provide a solid estimation of the state of research publication on NCD priority interventions in LMICs.

Conclusions

Research activity around NCD prevention priority interventions in LMICs, while increasing, remains minimal and is particularly underdeveloped in certain topics and geographical regions. Though there is still a need for better epidemiologic evidence on diseases and risk factors, there should also be a clear emphasis on local intervention and implementation research. Given the limited resources available for NCD research, there is a need to strike a balance between generating evidence to ‘understand the problem’ versus generating evidence more directly related to the implementation and evaluation of population-wide interventions. The less than perfect picture about the scale of the problem should not be used as an argument to postpone cost-effective measures for NCD prevention or the commitments laid out in the UN High-Level Meeting on NCDs will not be met.

Finally, the global research funding agenda should be influenced to provide more resources for NCD priority intervention research in LMICs. In general, there is a huge gap in the research funding available for developed countries versus developing countries Citation54. The Political Declaration adopted at the UN High Level Meeting on NCDs succeeded in firmly establishing NCDs as a global development issue requiring urgent action. However, development agencies have been slow to follow recommendations calling for an adjustment of current funding programs and the increased availability of resources targeting NCDs. Funding models should make it possible to take advantage of situations where policy changes have created a natural experimental setting Citation55–Citation57 and should also encourage and support local ownership, local leadership, and local translation of evidence to policy in order to increase the uptake of results by decision makers.

Conflict of interest and funding

Amanda Jones is supported by a Research Award from the International Development Research Centre (IDRC); Robert Geneau is an employee of IDRC. The publication fee was funded by the Non-Communicable Disease Prevention program, IDRC.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the role of Sachiko Okuda, whose expertise in bibliographic methods contributed to the search strategy design, and Mark Bisby, whose feedback was essential in the study design. We thank the African participants at the Consortium for Non-Communicable Disease Prevention and Control in Sub-Saharan Africa 2011 workshop in Nairobi, Kenya for their comments on early versions of this work. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors, and do not necessarily represent those of IDRC or its Board of Governors.

References

- World Health Organization. The global burden of disease: 2004 update. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2008. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GBD_report_2004update_full.pdf [cited 12 July 2011].

- World Economic Forum, World Health Organization. From burden to “best buys”: reducing the economic impact of non-communicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries. ColognySwitzerland: World Economic Forum. 2011. Available from: http://www.who.int/nmh/publications/best_buys_summary.pdf [cited 1 September 2011].

- United Nations News Service Section. UN agency lauds assembly resolution on non-communicable diseases. 2010. Available from: http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=34698&Cr=who&Cr1=disease [cited 7 September 2011].

- United Nations. Political declaration of the high-level meeting of the general assembly on the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases. 2011. Available from: http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/66/L.1 [cited 24 September 2011]..

- Beaglehole R, Bonita R, Horton R, Adams C, Alleyne G, Asaria P, et al.. Priority actions for the non-communicable disease crisis. Lancet. 2011; 377: 1438–47. Available from: http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736%2811%2960393-0/abstract [cited 16 May 2011].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- World Health Organization. Global status report on non-communicable diseases 2010. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2011. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789240686458_eng.pdf [cited 21 September 2011].

- World Health Organization. Scaling up action against non-communicable diseases: how much will it cost?. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2011. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241502313_eng.pdf [cited 26 September 2011].

- Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2006; 367: 1747–57. Available from: http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0140673606687709/1-s2.0-S0140673606687709-main.pdf?_tid=e9ff2396e0adb22b943b61a1082fda6f&acdnat=1337867069_bb206ad1498a70bdfda5766e6ef34c58 [cited 7 September 2011].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- Maher D, Sekajugo J. Research on health transition in Africa: time for action. Health Res Policy Syst. 2011; 9: 5–8. Available from: http://www.health-policy-systems.com/content/pdf/1478-4505-9-5.pdf [cited 28 October 2011].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Medicine. 2006; 3: 2011–30. Available from: http://www.plosmedicine.org/article/fetchObjectAttachment.action;jsessionid=FAE79AAC115B7BA3EFD38F5B0451822C?uri=info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pmed.0030442&representation=PDF [cited 6 September 2011].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- Abrahams Z, Mchiza Z, Steyn NP. Diet and mortality rates in Sub-Saharan Africa: stages in the nutrition transition. BMC Public Health. 2011; 11: 801. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1471-2458-11-801.pdf [cited 10 February 2012].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- Miranda J, Kinra S, Casas J, Davey Smith G, Ebrahim S. Non-communicable diseases in low-and middle-income countries: context, determinants and health policy. Trop Med Int Health. 2008; 13: 1225–34. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2687091/pdf/ukmss-5009.pdf [cited 26 September 2011].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- Ebrahim S, Smith GD. Exporting failure? Coronary heart disease and stroke in developing countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2001; 30: 201–5. Available from: http://ije.oxfordjournals.org/content/30/2/201.full.pdf+html [cited 7 March 2012].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- Miranda JJ, Zaman MJ. Exporting “failure”: why research from rich countries may not benefit the developing world. Rev Saude Publica. 2010; 44: 185–9. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rsp/v44n1/20.pdf [cited 8 November 2011].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- Hofman K, Ryce A, Prudhomme W, Kotzin S. Reporting of non-communicable disease research in low- and middle-income countries: a pilot bibliometric analysis. J Med Libr Assoc. 2006; 94: 415–20. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1629422/pdf/i1536-5050-094-04-0415.pdf [cited 5 May 2011].

- Fuster V, Kelly B. Promoting cardiovascular health in the developing world: a critical challenge to achieve global health. Washington DC: The National Academies Press. 2010. Available from: http://www.nap.edu/nap-cgi/report.cgi?record_id=12815&type=pdfxsum [cited 8 November 2011].

- Ranson MK, Jha P, Chaloupka FJ, Nguyen SN. Global and regional estimates of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of price increases and other tobacco control policies. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002; 4: 311–19. Available from: http://www.impacteen.org/fjc/PublishedPapers/Nicotine_TobaccoRanson2002.pdf [cited 9 November 2011].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- Asaria P, Chisholm D, Mathers C, Ezzati M, Beaglehole R. Chronic disease prevention: health effects and financial costs of strategies to reduce salt intake and control tobacco use. Lancet. 2007; 370: 2044–53. Available from: http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140673607616985/abstract [cited 9 November 2011].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- Murray CJL, Lauer JA, Hutubessy RCW, Niessen L, Tomijima N, Rodgers A, et al.. Effectiveness and costs of interventions to lower systolic blood pressure and cholesterol: a global and regional analysis on reduction of cardiovascular-disease risk. Lancet. 2003; 361:717–25. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673603126554 [cited 9 November 2011].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- Willet WC, Koplan JP, Nugent R, Dusenbury C, Puska P, Gaziano TA. Prevention of chronic disease by means of diet and lifestyle changes. Disease control priorities in developing countries. Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB, et al..Oxford University Press. New York NY, 2006; 869–85.

- World Health Organization. Nutrition labels and health claims: the global regulatory environment. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2004. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2004/9241591714.pdf [cited 12 December 2011].

- Cecchini M, Sassi F, Lauer J, Lee Y, Guajardo-Barron V, Chisholm D. Tackling of unhealthy diets, physical inactivity, and obesity: health effects and cost-effectiveness. Lancet. 2010; 376: 1775–84. Available from: http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736%2810%2961514-0/abstract [cited 27 May 2011].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- Chow CK, Lock K, Teo K, Subramanian SV, McKee M, Yusuf S. Environmental and societal influences acting on cardiovascular risk factors and disease at a population level: a review. Int J Epidemiol. 2009; 38: 1580–94. Available from: http://ije.oxfordjournals.org/content/38/6/1580.full.pdf+html [cited 10 November 2011].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- Anderson P, Chisholm D, Fuhr DC. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of policies and programmes to reduce the harm caused by alcohol. Lancet. 2009; 373: 2234–46. Available from: http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0140673609607443/1-s2.0-S0140673609607443-main.pdf?_tid=c734b5cd0a50adbf822486639a62c860&acdnat=1337888461_f47a0f7c289b66989bb7c9b2e583a8ed [cited 27 May 2011].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- The World Bank. Country and lending groups. Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-classifications/country-and-lending-groups [cited 30 May 2011].

- SciVerse. What does it cover?. Available from: http://www.info.sciverse.com/scopus/scopus-in-detail/facts [cited 19 September 2011].

- SciVerse Scopus. Content coverage guide. Elsevier B.V. 2011. Available from: http://www.info.sciverse.com/UserFiles/sciverse_scopus_content_coverage_0.pdf [cited 19 September 2011].

- Nykiforuk C, Osler G, Viehbeck S. The evolution of smoke-free spaces policy literature: a bibliometric analysis. Health Policy. 2010; 97: 1–7. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0168851010000771 [cited 30 May 2011].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- World Health Organization. Parties to the WHO framework convention on tobacco control. Geneva: WHO. 2012. Available from: http://www.who.int/fctc/signatories_parties/en/index.html [cited 24 July 2012].

- Wipfli HL, Samet JM. Moving beyond global tobacco control to global disease control. Tob Control. 2011; 21: 269–72. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/early/2011/12/14/tobaccocontrol-2011-050322.full.pdf+html [cited 24 March 2012].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- Casswell S, Thamarangsi T. Reducing harm from alcohol: call to action. The Lancet. 2009; 373: 2247–57. Available from: http://www.lancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(09)60745-5/abstract [cited 24 January 2012].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- Gupta BM, Bala A. A bibliometric analysis of malaria research in India during 1998–2009. J Vector Borne Dis. 2011; 48: 163–70. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21946717 [cited 19 March 2012].

- Mony PK, Srinivasan K. A bibliometric analysis of published non-communicable disease research in India. Indian J Med Res. 2011; 134: 232–4. Available from: http://ukpmc.ac.uk/articles/PMC3181025;jsessionid=hU6dA0rccis5cCdctUH3.0 [cited 15 December 2011].

- Mendis S, Yach D, Bengoa R, Narvaez D, Zhang X. Research gap in cardiovascular disease in developing countries. The Lancet. 2003; 361: 2246–7. Available from: http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736%2803%2913753-1/fulltext [cited 8 November 2011].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- Daar AS, Singer PA, Persad DL, Pramming SK, Matthews DR, Beaglehole R, et al.. Grand challenges in chronic non-communicable diseases. Nature. 2007; 450: 494–6. Available from: http://oxha.org/images/journal-articles/Daar2007.pdf [cited 8 June 2011].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- Mendis S, Alwan A. A prioritized research agenda for prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2011. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241564205_eng.pdf [cited 5 September 2011].

- Falagas ME, Karavasiou AI, Bliziotis IA. A bibliometric analysis of global trends of research productivity in tropical medicine. Acta Tropica. 2006; 99: 155–9. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0001706X06001550 [cited 21 March 2012].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- Sumathipala A, Siribaddana S, Patel V. Under-representation of developing countries in the research literature: ethical issues arising from a survey of five leading medical journals. BMC Med Ethics. 2004; 5: E5. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6939/5/5 [cited 17 November 2011].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- Pastrana T, Vallath N, Mastrojohn J, Namukwaya E, Kumar S, Radbruch L, et al.. Disparities in the contribution of low- and middle-income countries to palliative care research. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010; 39: 54–68. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19892510 [cited 21 March 2012].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- Aaron GJ, Wilson SE, Brown KH. Bibliographic analysis of scientific research on selected topics in public health nutrition in West Africa: review of articles published from 1998 to 2008. Glob Public Health. 2010; 5(sup1): S42–S57. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/17441692.2010.526128 [cited 22 March 2012].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- IJsselmuiden C. Mapping Africa's advances public health education capacity: the AfriHealth project. Bull World Health Organ. 2007; 85: 914–22. Available from: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/85/12/07-045526.pdf [cited 26 March 2012].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- Horton R. North and south: bridging the information gap. Lancet. 2000; 355: 2231–6. Available from: http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736%2805%2972659-3/fulltext [cited 17 November 2011].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- Rohra DK. Representation of less-developed countries in pharmacology journals: an online survey of corresponding authors. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011; 11: 60. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1471-2288-11-60.pdf [cited 21 March 2012].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- Yousefi-Nooraie R, Shakiba B, Mortaz-Hejri S. Country development and manuscript selection bias: a review of published studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006; 6: 37. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1550721/ [cited 11 November 2011].

- Shakiba B, Salmasian H, Yousefi-Nooraie R, Rohanizadegan M. Factors influencing editors’ decision on acceptance or rejection of manuscripts: the authors’ perspective. Arch Iran Med. 2008; 11: 257–62. Available from: http://www.mededit-online.com/images/Shakiba_et_al--factors_influencing_editors_decision_to_reject_or_accept.pdf [cited 23 March 2012].

- Adam T, Ahmad S, Bigdeli M, Ghaffar A, Røttingen J-A. Trends in health policy and systems research over the past decade: still too little capacity in low-income countries. PLoS One. 2011; 6: e27263. Available from: www.plosone.org/article/fetchObjectAttachment.action;jsessionid=C640932CFDCD4274E8E3194F707FD8BE?uri=info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0027263&representation=PDF [cited 16 March 2012].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- Alwan A, Maclean DR, Riley LM, d’ Espaignet ET, Mathers CD, Stevens GA, et al.. Monitoring and surveillance of chronic non-communicable diseases: progress and capacity in high-burden countries. Lancet. 2010; 376: 1861–8. Available from: http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736%2810%2961853-3/abstract.10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- Geneau R, Stuckler D, Stachenko S, McKee M, Ebrahim S, Basu S, et al.. Raising the priority of preventing chronic diseases: a political process. Lancet. 2010; 376: 1689–98. Available from: http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736%2810%2961414-6/abstract [cited 26 October 2011].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- Director-General. Global strategy for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2000. Available from: http://apps.who.int/gb/archive/pdf_files/WHA53/ea14.pdf [cited 16 March 2012].

- World Health Organization. 2008–2013 Action plan for the global strategy for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2008. Available from: http://www.who.int/nmh/Actionplan-PC-NCD-2008.pdf [cited 16 March 2012].

- World Health Organization. WHO framework convention on tobacco control. Geneva: WHO. Available from: http://www.who.int/fctc/en/ [cited 16 March 2012]..

- World Health Organization. Global strategy on diet, physical activity, and health. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2004. Available from: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/strategy/eb11344/strategy_english_web.pdf [cited 8 November 2011].

- World Health Organization. Global strategy to reduce the harmful use of alcohol. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2010. Available from: http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/alcstratenglishfinal.pdf [cited 8 November 2011].

- Edejer TT-T. North-South research partnerships: the ethics of carrying out research in developing countries. BMJ. 1999; 319: 438–41. Available from: http://www.bmj.com/highwire/filestream/372575/field_highwire_article_pdf/0.pdf [cited 23 March 2012].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- Herttua K, Mäkelä P, Martikainen P. An evaluation of the impact of a large reduction in alcohol prices on alcohol-related and all-cause mortality: time series analysis of a population-based natural experiment. Int J Epidemiol. 2011; 40: 441–54. Available from: http://ije.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2009/12/07/ije.dyp336.full.pdf+html [cited 23 February 2012].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- Ogilvie D, Griffin S, Jones A, Mackett R, Guell C, Panter J, et al.. Commuting and health in Cambridge: a study of a “natural experiment” in the provision of new transport infrastructure. BMC Public Health. 2010; 10: 703. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1471-2458-10-703.pdf [cited 23 March 2012].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.

- Petticrew M, Cummins S, Ferrell C, Findlay A, Higgins C, Hoy C, et al.. Natural experiments: an underused tool for public health?. Public Health. 2005; 119: 751–7. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0033350605000296 [cited 23 March 2012].10.3402/gha.v5i0.18847.