Abstract

Community-based care (CBC) can increase access to key services for people affected by HIV/AIDS through the mobilization of community interests and resources and their integration with formal health structures. Yet, the lack of a systematic framework for analysis of CBC focused on HIV/AIDS impedes our ability to understand and study CBC programs. We sought to develop taxonomy of CBC programs focused on HIV/AIDS in resource-limited settings in an effort to understand their key characteristics, uncover any gaps in programming, and highlight the potential roles they play. Our review aimed to systematically identify key CBC programs focused on HIV/AIDS in resource-limited settings. We used both bibliographic database searches (Medline, CINAHL, and EMBASE) for peer-reviewed literature and internet-based searches for gray literature. Our search terms were ‘HIV’ or ‘AIDS’ and ‘community-based care’ or ‘CBC’. Two co-authors developed a descriptive taxonomy through an iterative, inductive process using the retrieved program information. We identified 21 CBC programs useful for developing taxonomy. Extensive variation was observed within each of the nine categories identified: region, vision, characteristics of target populations, program scope, program operations, funding models, human resources, sustainability, and monitoring and evaluation strategies. While additional research may still be needed to identify the conditions that lead to overall program success, our findings can help to inform our understanding of the various aspects of CBC programs and inform potential logic models for CBC programming in the context of HIV/AIDS in resource-limited settings. Importantly, the findings of the present study can be used to develop sustainable HIV/AIDS-service delivery programs in regions with health resource shortages.

The Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) estimated that globally approximately 34.2 million people were living with HIV in 2011 (Citation1). Sub-Saharan Africa remains the most heavily affected region (Citation2, Citation3). While coverage remains low in many settings (Citation4, Citation5), access to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has increased in recent years, with more than 6 million people in low- and middle-income countries receiving treatment in 2010 (Citation1). Increased availability of antiretroviral therapy (ART) has not only dramatically increased survival but has also changed the clinical management of HIV (Citation6) requiring increasing numbers of trained health workers to effectively deliver treatment (Citation7).

The chronic shortage of health workers amplifies this challenge. According to the Global Health Workforce Alliance, 1.5 million more health care workers are needed in sub-Saharan Africa alone just to be able to provide basic health services (Citation8). Furthermore, high healthcare costs and lack of adequate healthcare infrastructures further decreases the ability to deliver HIV services in resource-limited regions (Citation9–Citation12). Decentralizing HIV services through community-based approaches has been used in many regions with limited healthcare resources to overcome the challenges imposed by the scale of the HIV/AIDS epidemic (Citation13–Citation15).

There is currently no single consensus definition of community-based care (CBC) (Citation16). It can mean different things, have different uses, and play different roles for different actors (e.g. program implementers, policy makers, donors). Within the context of HIV/AIDS, CBC includes ‘all AIDS activities that are based outside conventional health services (hospital, clinic, and health centre), but which may have linkages with the formal health and welfare sector, and which address an aspect of the continuum of care from the time of infection through to death’ (Citation17). The World Health Organization (WHO) defines CBC as care that ‘the consumer can access nearest to home, and which encourages participation by people, responds to the needs of people, encourages traditional community life, and creates responsibilities’ (Citation18). Home-based care (HBC) and CBC are two closely related concepts. HBC can be defined as ‘the provision of services by formal and informal caregivers in the home’ (Citation18). As such, HBC is often an integral part of CBC. While there are common components of CBC programs across settings (Citation19, Citation20), the specifics of a given model depend on contextual factors, including national policy, non-governmental organizations’ (NGO) missions, and available resources.

The use of community health workers (CHWs) was integrated into primary healthcare reform in the 1970s (Citation21, Citation22). As the HIV pandemic took hold in sub-Saharan Africa, CHWs were frequently responsible for disease monitoring and patient support tasks (Citation18, Citation23). In the 1990s, CBC programs that addressed various aspects of the HIV/AIDS continuum of care (e.g. testing and counseling services, medical and social support) were introduced in countries affected by the epidemic (Citation15, Citation23).

With the scale-up of ART in the global South came new challenges: delivering treatment to those in need and providing lifelong care for those now on life-extending treatment (Citation24–Citation27). To maximize access to ART with scarce health professional resources, health planners have shown renewed interest in the potential role of community-based programs and CHWs in ART monitoring. Physician-centered models in many settings have given way to those reliant on trained non-physician health workers (Citation13, Citation26, Citation28). Nurse-driven ART in Lesotho (Citation28), the use of community-based Health Surveillance Assistants (HSAs) to dispense ART and monitor stable patients in one region of Malawi (Citation29), and community care coordinators in Kenya (Citation13) are examples of such ‘task-shifting’. Individual CBC programs have been shown to increase access to essential services for people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) and their families (Citation30, Citation31) through the mobilization of community interests and resources as well as the development of appropriate tools, including training and referral, to integrate these with formal health structures (Citation15, Citation19). Available data suggest that CBC programs can promote awareness while reducing stigma, reduce the burden on the primary care system, and ultimately decrease the incidence of hospitalization (Citation32, Citation33). In the context of treatment scale-up, some CBC programs shifted their focus in order to encourage optimal adherence to ART, supporting better treatment outcomes. Evidence suggests that at least in some settings, viral load suppression and adherence may be improved in community-based programs relative to clinic-based care (Citation7, Citation34).

With ART coverage increasing in many settings, understanding the role of CBC programs becomes more and more important (Citation16). Related to this is the need to understand how CBC programs can target and support vulnerable and marginalized populations that continue to face barriers in terms of knowledge about HIV and its prevention, treatment, support, and care, and in terms of access to these services (Citation35, Citation36). Rollout of ART to vulnerable populations may require alternative approaches that work best when communities and community resources are engaged in the process (Citation7). Significantly, there is evidence suggesting that CHW programs have not always been successful (Citation30). The mix of activities in CBC programs make them difficult to study, limiting the explicitness and comparability of what have, to date, been primarily program-specific evaluations (Citation16). While such evaluations are important for providing evidence of programs’ effectiveness, they need to be accompanied by analyses that identify the conditions necessary for effective and sustainable program implementation (Citation15, Citation37). A 2012 review of community-based organizations (CBOs) that sought to identify and conceptually map existing peer-reviewed literature related to the characteristics of CBOs in the health sector noted significant gaps in our understanding of CBOs in low- and middle-income countries (Citation16). Furthermore, an absence of explicit conceptual frameworks in such settings continues to limit our ability to understand and study health policy (Citation38). We sought to develop a taxonomy of CBC programs focused on HIV/AIDS in resource-limited settings in an effort to identify and describe their key characteristics, uncover any gaps in programming, and highlight the potential roles they play.

Present investigation

Methods

We conducted electronic searches of health bibliographic databases including PubMed via Medline (from inception to December 2011), CINAHL (from inception to December 2011), and EMBASE (from inception to December 2011). Our search terms were ‘HIV’ or ‘AIDS’ and ‘community-based care’ or ‘CBC’. Additional articles were sought by examining the bibliographies of relevant articles. For the gray literature, we used the same search terms in Google and Google Scholar to identify program descriptions, study reports, and publications of official materials issued by non-governmental organizations, government health services, and international agencies. Site-specific searches of the UNAIDS and WHO websites were also undertaken.

In the present study, only CBC programs operating in resource-limited country settings were included. We defined resource-limited as a low-income or middle-income country using the World Bank Country Classification (Citation39). As we believe this to be the first comprehensive review focusing on CBC programs related to HIV in resource-limited settings, we used a broad definition of CBC. It encompassed any self-identified CBC program focused on HIV prevention, treatment, care, and support that reported any level of community participation in the planning and/or delivery of care. However, in order to develop the taxonomy, our inclusion criteria required that programs provided adequate descriptions on program origins/mission, structure, populations served, and day-to-day activities.

For analysis, we undertook an inductive and iterative process to develop our taxonomy of CBC programs. First, Beth Rachlis (BR) conducted the search of potentially relevant CBC programs (as case studies) and determined which programs provided data based on our inclusion criteria. Next, BR extracted all descriptions from each included CBC program. From the gathered information and using an inductive approach, BR and Sumeet Sodhi (SS) sorted the data and descriptions extracted from each individual program into broader categories, in an iterative process. Finally, we sought to organize the information into distinct and mutually exclusive categories (e.g. program scope vs. program operations). For content validation, we ensured that the information described and extracted from most individual programs could be categorized as per our developed taxonomy.

Results

Our initial search of the literature returned 2,524 citations, of which 83 were considered potentially relevant. Of these, 64 were excluded because they did not describe a CBC program (n=45), were not based in a resource-limited setting (n=10), or were duplicates (n=9). We updated our literature search in February 2012 and found two additional programs that were relevant. Therefore, 21 CBC programs (Citation14, Citation19, Citation30, Citation34, Citation40–Citation53) met our inclusion criteria and were included. describes our taxonomy and describes the nature of the included CBC programs.

Table 1 Taxonomy of community-based care (CBC) programs

Table 2 Program descriptions by taxonomy categories

Region

CBC programs can be classified according to the geographic region in which they operate. While some programs, for example, ‘Men as Partners’ and ‘Pathfinder International’, operate globally, most programs we identified only work in one country, for example, Moretele Sunrise Hospice operates only in South Africa.

Vision

Most of the included CBC programs described their program vision. This can be very broad such as the vision of The Aids Support Organization (TASO) of ‘a world without AIDS’ or Dignitas’ pledge ‘to stand up for those who lack access’. Most included programs provided a mission statement to describe what they seek to accomplish. Examples include the Centre for Positive Care ‘to reduce the spread of Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs), HIV/AIDS, and to improve the quality of life’; SERVANTS to ‘improve the lives of the poor’; or Men as Partners to ‘mobilize men to become actively involved in countering HIV and gender-based violence’.

Characteristics of target population

Urban–rural location can influence program delivery options and resources. The majority of CBC programs in this study described working with urban populations (e.g. Catholic Diocese in Ndola, SERVANTS) although semi-rural (e.g. Tumelong Hospice) and rural (e.g. Chirumhanzu HBC) settings were also represented. A few included programs serve both rural and more urban populations (e.g. FACT). While CBC programs focused on HIV seek to work with PLWHA, many programs also cater to others affected by HIV – family members (e.g. Centre for Positive Care) and orphans and vulnerable children (OVCs) (e.g. FACT/FOCUS, Hope Worldwide Siyawela Community Child Care). Less common were programs that work with high-risk populations such as prisoners or migrants (e.g. Dignitas International, SERVANTS). Pathfinder International specifically described targeting marginalized populations, including drug users, sex workers, and displaced persons.

Program scope (services provided)

Two broad categories were judged relevant here – location and types of services provided. In terms of location, some programs only describe operating directly inside the private homes of their clients through home-based care (e.g. Moretele Sunrise Hospice HBC) while others report operating in more shared community settings (e.g. Men as Partners, Reach Out Mbuya). Most commonly, programs provide care both inside and outside of the home, with some aiming for multiple locations, including a clinic or hospital (e.g. Lusikisiki Clinic).

CBC programs differed most on the range of services provided as we noted heterogeneity regarding types of services provided over different time points along the continuum of care. Common services reported include HIV prevention, including risk reduction activities (e.g. Centre for Positive Care, STEPS); HIV Testing and Counseling (HTC) (e.g. HIV Equity Initiative); Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission (PMTCT) (e.g. Centre for Positive Care); ART provision and follow-up, including adherence monitoring (e.g. Dignitas International, Lusikisiki Clinic); medical and nursing support, including treatment of STIs and management of symptoms and opportunistic infections (e.g. Catholic Diocese in Ndola, Centre for Positive Care, Reach Out Mbuya); nutrition support and food supplementation (e.g. FACT); palliative care (e.g. Tumelong Hospice and Lekegema Orphan Haven); financial support in the form of income-generating activities (IGA) or community funds (e.g. Khutsong Centre and Heartbeat Orphan Programme); material support, including technical support; information, communication, and education activities (e.g. AIDS Foundation, Chirumhangu HBC project, Pathfinder International); and psychosocial support (e.g. Catholic Diocese in Ndola). Such heterogeneity is at the core of challenges involved in evaluating outcomes of such programs.

Program operations

A number of important characteristics relate to the manner in which programs situate themselves in relation to community structures. First, we found that programs can be classified by the extent of community engagement and/or participation. In some CBC programs, community leaders or volunteers are included in overall operations management (e.g. Catholic Diocese in Ndola). Almost all programs where detail was provided implied the need to maintain and incorporate community life. For example, by seeking to build on traditions of family support, Chirumhanzu HBC project encourages a mutual obligation in the way they run their programs and deliver their services. Programs like FACT and Reach Out Mbuya incorporate church life, and in programs like the Thandanani Children's Foundation, it is the community leaders and the residents that primarily identify at risk individuals in need of their services. The number of partners and collaborators not only affects program operations but also may reflect a program's ability to build capacity in the broader community. In terms of program reach, not all included CBC program descriptions had available data, but among those that did, most have at least sub-district (e.g. Luskikiki clinic) or district-level reach (e.g. Dignitas International). Programs like TASO, STEPS, and Moretele Sunrise Hospice HBC serve patients in more than one district and can be considered multisite. To achieve coverage, programs decentralize (e.g. Dignitas International, Lusikisiki Clinic) or, through advocacy, they mobilize communities (e.g. Thandanani Children's Foundation). Finally, the extent to which CBC programs are embedded within formal health and social structures varies. Most programs reported linkages and collaborations with local organizations and government structures/ministries (e.g. Tumelong Hospice, Pathfinder International, Lekegema Orphan Haven). However, some of the programs described operate independently (e.g. HIV Equity Initiative/Zamni-Lasanti).

Funding models

Financial aspects of the program are crucial – identifying who funds the program and how the funds are disbursed. Sources of funds described ranged widely between programs, with common sources including a combination of local and foreign governments (e.g. Chirumhanzu HBC, Khutsong Centre, and Heartbeat Orphan Programme), private donors (e.g. AIDS Foundation, Dignitas International), national or international NGOs (e.g. Centre for Positive Care, STEPS, Dignitas International), and individuals and businesses within the community (e.g. Khutsong Centre and Heartbeat Orphan Programme, Tumelong Hospice, and Lekegema Orphan Haven). Program costs and budgets were generally not provided in the sources examined. A few programs, such as Pathfinder International, did make their annual financial reports that documented expenses publicly available.

Human resources

The organizational structure and staff composition of the CBC programs varied considerably, particularly with respect to the type of CHWs involved (e.g. nurses, clinical officers). The exact hierarchical structure was described only in a few programs (e.g. Pathfinder International), although most provided information on the presence of a board of directors (e.g. AIDS Foundation, TASO), advisory boards (e.g. Khutsong Centre and Heartbeat Orphan Programme, TASO), or other governance groups (e.g. HIV Equity Initiative). Some programs only described recruiting volunteers (e.g. SERVANTS) although more common were programs where a combination of paid staff and volunteers were recruited (e.g. HIV Equity Initiative, Lusikisiki Clinic). The methods, frequency, and level of training also ranged across included programs, as did the extent of volunteer and staff supervision or mentoring. When described, common strategies included on-the-job or ongoing training (e.g. Moretele Sunrise Hospice) or the provision of training sessions on specific topics (e.g. Project Hope, TASO). Among programs where information was available, management and supervision levels also varied although included programs commonly described incorporating a coordinator to supervise volunteers (e.g. Catholic Diocese in Ndola, Centre for Positive Care). Foreign doctors or senior nurses also provide supervision in programs such as Dignitas International, Lusikisiki Clinic, and HIV Equity Initiative. Some programs describe peer-based activities, including Pathfinder International and TASO's ‘training of the trainers’ program.

Sustainability

According to our taxonomy, key factors influencing the sustainability of CBC programs include the availability of ongoing funding, the ability of the program to adapt to local contexts and to replicate itself in new settings, and high staff retention levels. According to the included programs, strategies used to retain staff include providing volunteers with a stipend or other incentives such as recreational activities and family support (e.g. Centre for Positive Care, SERVANTS, Thandanani Children's Foundation). Also, important for sustainability of programs is their ability to adapt to any changing local contexts and situations and, where appropriate, their replicability in new settings. We found few programs describing such replication; examples include STEPS and the HIV Equity Initiative. Dissemination, capacity building, and knowledge translation activities were described in several programs (e.g. Dignitas International, TASO).

Monitoring and evaluation

Finally, the frequency and comprehensiveness of monitoring and evaluation activities varied. Programs such as the Catholic Diocese in Ndola described conducting biannual evaluations although specific details regarding these evaluations were generally not provided. Some programs provided quality indicators (e.g. AIDS Foundation, Lusikisiki Clinic, Kapit Kamay Sa Bagong Pag-Asa) or potential program impacts (e.g. TASO, Men as Partners) and have a specific team for evaluation and monitoring activities (e.g. Pathfinder International). Inputs, such as management structures and financial accountability (e.g. STEPS), and outcomes, such as changes in behaviors (e.g. TASO, Men as Partners) and clinical outcomes (e.g. Lusikisiki Clinic), were also described with respect to monitoring and evaluation activities.

Discussion

The taxonomy presented here elaborates nine key categories useful for describing and organizing CBC programs focused on HIV/AIDS in resource-limited settings. Our findings can help to identify what is currently being done with respect to addressing the needs of PLWHA, highlighting any potential gaps in programming.

Key characteristics of identified CBC programs

The majority of CBC programs included in our review described programs operating in sub-Saharan Africa, which is consistent with previous literature (Citation9, Citation48).

Visions and program missions varied, although generally identified CBC programs strive to improve the lives of those living with HIV/AIDS. The specificity of the program's mission not only impacts upon the types of services offered but can also affect a program's ability to expand and adapt into new settings. While the vast majority of included programs targeted PLWHA, many also incorporated other affected populations, including family members and OVCs. A few CBC programs included vulnerable populations, such as drug users and migrant workers. Marginalized populations remain a priority population for HIV care, treatment, and support although they are generally underserved (Citation16). Few programs provided data on the gender make-up of the populations being served. Further detail on the number of men and women receiving services would provide meaningful data in terms of coverage and equity of access to services. Currently, there is an absence of gender-specific data on patient-retention in ART programs and as a result there is conflicting evidence as to whether men or women are more likely to access ART (Citation54, Citation55).

The types of services offered varied considerably among the CBC programs studied, although most described providing services both in the home and in more public community settings. Interestingly, in a review of South African CBC models, four common program types emerged: 1) funding, technical assistance, and support; 2) counseling, education, and an IGA component; 3) the two aforementioned points plus home visits; and finally, 4) comprehensive programs which add to item 3) above, additional levels of nursing care (Citation17). Adding the location of services provides additional insight as to where the majority of programs provide care as well as where there may be gaps. Not surprisingly, almost all included programs provided care both in the home and in the community. Relatively few provided care only in the community or only in the home. Further assessment may help to identify services that are not offered. Marginalized groups, including injection drug users, may require other service locations or additional services, including harm reduction approaches.

Operational models also differed across programs included in the present review. In particular, the level of community engagement appeared to vary, as evidenced by the number and nature of collaborations and partnerships with community groups, members, and leaders. Importantly, the ability to build and maintain collaborations with community partners is essential to ongoing program operations. Related is how CBC programs are embedded within existing formal structures which include: the identification of community partners for potential collaboration, a sense of ownership by the community, their relevance to local needs, integration into existing systems, and periodic reviews and program updates with new knowledge (Citation56). The availability and comprehensiveness of existing health and/or social structures and institutions (e.g. hospitals, schools, businesses, and religious structures) may also affect the ability of CBC programs to engage in collaborations and may be a function of multiple other factors, including available funding. Further identification of how contextual factors such as local politics, political interests, economic reforms, and various forms of conflict can impact on the capacity of CBC programs to perform effectively and sustainably may be needed.

Funding models, human resources factors, and the sustainability of CBC programs have also been included as part of our taxonomy and are all essential elements of program impacts. Interestingly, a recent review noted that factors influencing HBC program effectiveness include those that relate to human resources, funding mechanisms, and an ability to adapt to local contexts (Citation37). Furthermore, sustainable project implementation has been identified as key for the scale-up and expansion of comprehensive HIV services in resource-limited countries (Citation37, Citation57, Citation58). While significant elements of sustainability [identified by Torpey et al., 2010 (Citation57)] include technical, programmatic, social, and financial forms of sustainability, in the present study, we found that the sustainability of programs is primarily related to the availability of ongoing funding and an ability to retain staff (Citation57). It may be worth noting that models may be challenged to involve community members fully in decision-making regarding program goals and activity planning specifically when the majority of funding comes from a single source based outside the community (Citation23). Current challenges related to funding, including the suspension of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria Round 11, holds very real implications for program sustainability. According to a Médecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) briefing note, several African countries have been forced to scale back on their programming (e.g. initiating new patients on ART) given budget and financial constraints (Citation59). With respect to staff retention, there remains a need to identify sustainable compensation methods that are equitable and fair. An ability to ensure minimal necessary staffing levels as well as ongoing training and mentorship are also key program challenges (Citation28) and yet are critical for program effectiveness and overall sustainability. Knowledge translation also plays an important role as the dissemination of successful strategies may be particularly useful for the long-term sustainability of programs as well as their scale-up and adoption other settings (Citation60).

While most programs make reference to some type of regular monitoring, many programs provided limited information regarding their monitoring and evaluation strategies or the information that was collected during their evaluations. However, CBOs are playing greater roles in both the design and implementation of research in order to effectively inform program and policy decisions (Citation16, Citation61). This underscores the need for adequate documentation and dissemination. Programs like TASO in Uganda capture regular data on clinical (e.g. proportion of patients with optimal adherence) and behavioral outcomes (e.g. disclosure of status, changes in community support) (Citation62).

Limitations

Several limitations must be considered when interpreting this review. First, the comprehensiveness of our review is limited because many CBC programs do not publish or make vital information publicly available. As our search strategy relied heavily on electronic resources, our review contains only those programs with access and capacity to publish their program details online. Even when data were available, not all CBC programs were included as we sought to represent typical, known programs. This may affect the generalizability of our taxonomy. More specifically, programs that solely target marginalized groups, including men who have sex with men, sex trade workers, and/or migrant populations, were underrepresented in our review. However, we did attempt to include a range of programs which, in addition to targeting the general population of PLWHA, targeted marginalized groups as well (e.g. Pathfinder International, AIDS Foundation). Furthermore, CBC programs originated from several regions, though not all. Nevertheless, the present study helps to disentangle general versus country-specific characteristics of CBC programs (Citation38, Citation63). Finally, as we did not contact the programs directly to obtain additional information, we may have missed important details or descriptions that would add to the comprehensiveness of our taxonomy. Case studies of individual CBC programs often differed in the information provided, and the limited detail regarding the methodologies used (e.g. sampling, biases) in non-peer-reviewed data included in this review make it difficult to assess the validity of these findings. Partly for this reason, we did not assess the quality of included reports.

Implications of presented taxonomy

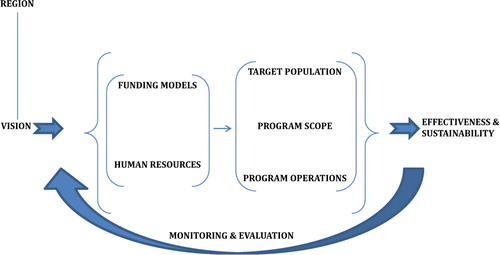

Huge sums of money are now being invested into multi-sectoral approaches and there have been extensive efforts to assess the effectiveness of traditional public health interventions in terms of prevalence rates and numbers of infections averted (Citation64). Currently, mitigation indicators are not capturing data on the impacts of programs themselves but rather tend to focus generally on inputs and outputs (i.e. number of orphans schooled, number of individuals tested) (Citation64). In , we present a potential logic model based on our taxonomy for CBC programs that may guide analyses of factors relevant for program effectiveness and sustainability.

Fig. 1 Potential program logic model for effective and sustainable CBC programming as informed by our presented taxonomy.

In brief, through a clear vision, a need for a program is identified. This overall vision or mission helps to motivate and guide program development, including the specification of a target population and program scope. The inputs to the program include available funding and human resources. These inputs are needed to provide the target population a certain set services (program scope) using a specific approach (program operations). These can be considered our outputs. The number of households captured or the number of eligible patients initiated on ART offer some examples of outputs that could be described. The overall program outcomes would be effectiveness, the degree to which the program is meeting its goals (Citation65), and sustainability. However, adequate monitoring and evaluation activities which feedback into all components of our model is fundamental for overall program performance.

Arguably, continuous feedback and quality improvement through regular monitoring and evaluation can facilitate any recommended rapid changes in the program to improve functioning and effectiveness (Citation13). Evaluation guidelines with clear indicators of success informed by collaborations with various partners and drawn from governmental or ministerial standards, guidelines, and operating procedures (Citation57) are required to ensure that programs are achieving their goals and objectives. Future research that seeks to develop a taxonomy of evaluation indicators useful for assessing CBC program effectiveness may be needed. Evaluation tools should include various process and output indicators, both broad and specific, and should be able to collect data on both patient-level outcomes as well as program outcomes (Citation65).

Important considerations include whether programs have identified resources for monitoring and evaluation activities. Improved methods for data collection, clearly defined indicators of success, and well-maintained ongoing monitoring and evaluation systems are crucial for program planning and effective implementation (Citation48, Citation66, Citation67). However, gaps in sustainable evaluation research capabilities have important implications with respect to the level of research that can be undertaken in resource-limited settings (Citation68). An operations research approach which considers real world conditions, including limitations, in the number and time of trained health workers and/or challenging research environments may offer a particularly useful method for conducting key monitoring and evaluation activities in such settings (Citation69).

Conclusions

High costs and a lack of adequate health infrastructure can challenge the scale-up and uptake of HIV-related services in resource-limited settings. Chronic health worker shortages have resulted in the decentralization of HIV care and a movement toward the use of non-physician-based models of care (Citation14, Citation28, Citation70). CBC programs can encourage partnerships among different stakeholders and sectors and build on the supportive community networks that already exist for PLWHA (Citation9).

Our taxonomy, focused on HIV/AIDS in resource-limited settings, classifies CBC programs by nine key areas: region, vision, target populations served, program scope, program operations, funding models, human resources, sustainability, and monitoring and evaluation strategies. While further study is needed, our findings can provide insight on current CBC models as well as potential gaps in programming. Furthermore, the presented taxonomy can inform potential logic models that can be used to enhance overall program performance. In the context of ART scale up, our findings have potential for use in the development of evidence-based tools for sustainable HIV/AIDS-service delivery in regions currently facing, or at risk for, severe health resource shortages.

Conflict of interest and funding

No funding was received for this study. The authors declare that they have no competing interests other than those apparent through their affiliations.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to acknowledge Joel Pidutti for his assistance with the review of the literature.

References

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. World AIDS day report 2011. 2011; Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Report on the global AIDS epidemic. 2010; Geneva: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. World health statistics 2009. 2009; Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Montaner JS , Hogg R , Wood E , Kerr T , Tyndall M . The case for expanding access to highly active antiretroviral therapy to curb the growth of the HIV epidemic. Lancet. 2006; 388: 531–6.

- United States Agency for International Development, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, World Health Organization, U.S. Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. Coverage of selected services for HIV/AIDS prevention, care, and support in low- and middle-income countries in 2003. 2005; Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Hogg RS , O'Shaughnessy MV , Gataric N , Yip B , Craib K , Schechter MT , etal. Decline in deaths from AIDS due to new antiretrovirals. Lancet. 1997; 349: 1294.

- Kipp W , Konde-Lule J , Rubaale T , Okech-Ojony J , Alibhai A , Saunders DL . Comparing antiretroviral treatment outcomes between a prospective community-based and hospital-based cohort of HIV patients in rural Uganda. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2011; 11: S12.

- World Health Organization and the Global Health Worker Alliance. Scaling up, saving lives. Task force for scaling up education and training for health workers. 2008; Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Farmer P , Leandre F , Mukherjee JS , Claude M , Nevil P , Smith-Fawzi MC , etal. Community-based approaches to HIV treatment in resource-poor settings. Lancet. 2001; 358: 404–9.

- World Health Organization. Taking stock: health worker shortages and the response to AIDS. 2006; Geneva: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. Scaling up antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited settings: treatment guidelines for a public health approach. 2003; Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Kim JY , Farmer P . AIDS in 2006 – moving toward one world, one hope?. N Engl J Med. 2006; 355: 645–7.

- Wools-Kaloustian KK , Sidle JE , Selke HM , Vendanthan R , Kemboi EK , Boit LJ , etal. A model for extending antiretroviral care beyond the rural health centre. J Int AIDS Soc. 2009; 12: 22.

- Bedelu M , Ford N , Hilderbrand K , Reuter H . Implementing antiretroviral therapy in rural communities: the Lusikisiki model of decentralized HIV/AIDS care. J Infect Dis. 2007; 196: S464–8.

- Corbin JH , Mittlemark MB , Lie GT . Scaling-up and rooting down: a case study of North-South partnerships for health from Tanzania. Glob Health Action. 2012; 5: 10.

- Wilson MG , Lavis JN , Guta A . Community-based organizations in the health sector: a scoping review. Health Res Policy Syst. 2012; 10: 36.

- Russel M , Schneider H . A rapid appraisal of community-based HIV/AIDS care and support programs in South Africa. 2000; Johannesburg: University of Witwatersrand.

- Friedman I , Ramelepe M , Matjuis F , Lungile Bhengu L , Lloyd B , Mafuleka A , etal. Moving towards best practice: documenting and learning from existing community care/care workers programmes. 2007; Durban: Health Systems Trust.

- World Health Organization. Community home-based care in resource-limited settings: a framework for action. 2002; Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Ncama BP . Models of community/home-based care for people living with HIV/AIDS in Southern Africa. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2005; 16: 33–40.

- Walt G . CHWS: are national programmes in crisis?. Health Policy Plan. 1988; 3: 1–21.

- Cueto M . The origins of primary health care and selective primary health care. Am J Public Health. 2004; 94: 1864–74.

- Schneider H , Hlophe H , van Rensburg D . Community health workers and the response to HIV/AIDS in South Africa: tensions and prospects. Health Policy Plan. 2008; 23: 179–87.

- El Sadr W , Abrams E . Scale-up of HIV care and treatment: can it transform healthcare services in resource-limited settings?. AIDS. 2007; 21: S65–70.

- Schneider H , Blaauw D , Gilson D , Cabikuli N , Goudge J . Health systems and access to antiretroviral drugs for HIV in Southern Africa: service delivery and human resource challenges. Reprod Health Matters. 2006; 14: 12–23.

- Hermann K , Van Damme W , Pariyo G , Schouten E , Assefa Y , Cirera A , etal. Community health workers for ART in sub-Saharan Africa: learning from experience-capitalizing on new opportunities. Hum Resour Health. 2009; 7: 31.

- Philips M , Zachariah R , Venis S . Task shifting for antiretroviral treatment delivery in sub-Saharan Africa: not a panacea. Lancet. 2008; 371: 682–4.

- Cohen R , Lynch S , Bygrave H , Eggers E , Vlahakis N , Hilderbrand K , etal. Antiretroviral treatment outcomes from a nurse-driven, community-supported HIV/AIDS treatment programme in rural Lesotho: observational cohort assessment at two years. J Int AIDS Soc. 2009; 12: 23.

- McCoy D . Economic and health systems research on health workers in sub-Saharan Africa: drawing out themes from a case study of Malawi. 2007; Washington, DC: Paper presented at UNAIDS/World Bank Economic Reference Group (ERG). 3–4 May. Available from: http://www.ukzn.ac.za/heard/ERG/McCoyFINALDRAFT.pdf .

- Kadiyala S . Scaling-up HIV/AIDS interventions through expanded partnerships (STEPs) in Malawi. Discussion 179. 2004; Washington, DC: Food Consumption and Nutrition Division of the International Food Policy Research Institute.

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. Community home-based care for people living with HIV/AIDS in Zimbabwe. 2004; Geneva: International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies.

- Nsutebu EF , Walley JD , Mataka E , Simon CF . Scaling up HIV/AIDS and TB home-based care: lessons from Zambia. Health Policy Plan. 2001; 16: 240–7.

- Jackson H , Kerkoven R . Developing AIDS care in Zimbabwe: a case for residential centres?. AIDS Care. 1995; 7: 663–73.

- Chang LW , Alamo S , Guma S , Christopher J , Suntoke T , Omasete R , etal. Two year virologic outcomes of an alternative AIDS care model: an evaluation of a peer health worker and nurse staffed community-based program in Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009; 50: 276–82.

- Barton-Villagrana H , Bedney BJ , Miller RJ . Peer relationships among community-based organizations (CBO) providing HIV prevention services. J Prim Prev. 2002; 23: 215–34.

- Chillag K , Bartholow K , Cordeiro J , Swanson S , Patterson J , Stebbins S , etal. Factors affecting the delivery of HIV/AIDS prevention programs by community-based organizations. AIDS Educ Prev. 2002; 14: 27–37.

- Wringe A , Cataldo F , Stevenson N , Fakoya A . Delivering comprehensive home-based care programmes for HIV: a review of lessons learned and challenges ahead in the era of antiretroviral therapy. Health Policy Plan. 2010; 25: 352–62.

- Walt G , Shiffman J , Schneider H , Murray SF , Brugha R , Gilson L . ‘Doing’ health policy analysis: methodological and conceptual reflections and challenges. Health Policy Plan. 2008; 23: 308–17.

- World Bank. Country classification table. Available from: http://go.worldbank.org/K2CKM78CC0 [cited 30 October 2010].

- AIDS Foundation of South Africa. Available from: http://www.aids.org.za/index.htm [cited 2 February 2011].

- Centre for Positive Care. Available from: http://www.posicare.co.za/ [cited 2 February 2011].

- Dignitas International. Available from: http://www.dignitasinternational.org [cited 20 November 2010].

- EngenderHealth, Planned Parenthood Association of South Africa. Available from: http://www.engenderhealth.org/our-work/gender/men-as-partners.php [cited 20 March 2011].

- Family Health International. HIV/AIDS care and treatment: a clinical course for people caring for persons living with HIV/AIDS. Facilitators Guide. 2004; Durham, NC: Family Health International.

- Fikansa SC . Integrated AIDS programme, catholic diocese of Ndola. Paper presented at Workshop on Urban Micro-Farming and HIV-AIDS, Johannesburg, 15–26 August 2005. Available from: http://www.ruaf.org/files/paper8.pdf .

- DeJong J . A question of scale? The challenge of expanding of non-governmental organizations’ HIV/AIDS efforts in developing countries. 2007; New York, NY: Population Council. Available from: http://www.popcouncil.org/pdfs/horizons/qstnofscl.pdf .

- Pathfinder International. Available from: http://www.pathfind.org [cited 30 January 2011].

- Partners in Health. The PIH guide to community-based treatment of HIV in resource poor settings. 2nd ed. 2006; Boston, MA: Partners in Health.

- Reach Out Mbuya. Available from: http://www.reachoutmbuya.org [cited 15 January 2011].

- Tolfree D . A sense of belonging. Case studies in positive care options for children. 2009; London: Save the Children. Available from: http://www.savethechildren.org.uk/sites/default/files/docs/A_Sense_of_Belonging_1.pdf .

- Servants to Asia's Poor. Available from: http://www.servantsasia.org [cited 20 February 2011].

- Thandanani Children's Foundation. Available from: http://www.thandanani.org.za/ [cited 20 February 2011].

- The AIDS Support Organization. Available from: http://www.tasouganda.org [cited 13 December 2010].

- Braitstein P , Boulle A , Nash D , Brinkhof MW , Dabis F , Laurent C , etal. Gender and the use of antiretroviral treatment n resource-constrained settings: findings from a multicenter collaboration. J Women Health. 2008; 13: 513–19.

- Cornell M , Myer L , Kaplan R , Bekker LG , Wood R . The impact of gender and income on survival and retention in a South African antiretroviral therapy programme. Trop Med Int Health. 2009; 14: 722–31.

- Kenya Ministry of Health, National AIDS/STD Control Programme. National home-based care programme and service guidelines. 2002; Nairobi: Ministry of Health.

- Torpey K , Mwenda L , Thompson C , Wamuwi E , Van Damme W . From project aid to sustainable HIV services: a case study from Zambia. J Int AIDS Soc. 2010; 13: 19.

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Financial resources required to achieve universal access to HIV prevention, treatment, care and support. 2007; Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Medecins Sans Frontieres. Reversing HIV/AIDS? How advances are being held back by funding shortages. Available from: http://www.msfaccess.org/sites/default/files/MSF_assets/HIV_AIDS/Docs/AIDS_Briefing_ReversingAIDS_ENG_Feb2012Update.pdf [cited December 2011].

- Tugell P , Robinson V , Grimshaw J , Santesso N . Systematic reviews and knowledge translation. Bull World Health Organ. 2006; 84: 643–51.

- Bhan A , Singh JA , Upshur RE , Singer PA , Daar AS . Grand challenges in global health: engaging civil society organizations in biomedical research in developing countries. PLoS Med. 2007; 4: e272.

- Kaleeba N , Kalibala S , Kaseje M , Ssebbanja P , Anderson S , van Praaq E , etal. Participatory evaluation of counseling and social services of the TASO in Uganda. AIDS Care. 1997; 9: 13–26.

- Ogden J , Esim S , Grown C . Expanding the care continuum for HIV/AIDS: bringing carers into focus. Health Policy Plan. 2006; 21: 333–42.

- Gavian S , Galaty D , Kombe G , Gillespie S . Multisectoral HIV/AIDS approaches in Africa. How are they evolving. AIDS, poverty, and hunger. Challenges and responses. 2005; Washington: International Food Policy Research Institute. 221–44. Highlights of the International Conference on HIV/AIDS and Food and Nutrition Security, Durban, South Africa, 14–16 April.

- Lusthas C , Adrien MH , Anderson G , Carden F . Enhancing organizational performance: a tool for self-assessment. 1999; Ottawa: International Development Research Centre.

- Binswanger HP , Gillespie S , Kadiyala S , Gillespie S . Scaling up multisectoral approaches to combating HIV and AIDS. AIDS, poverty, and hunger. Challenges and responses. 2005; Washington: International Food Policy Research Institute. 199–220. Highlights of the International Conference on HIV/AIDS and Food and Nutrition Security, Durban, South Africa, 14–16 April.

- Suri A , Gan K , Carpenter S . Voices from the field: perspectives from community health workers on health care delivery in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J Infect Dis. 2007; 196: S505–11.

- Whitworth AG , Kowaro G , Kinyaniui S , Snewin VA , Tanner M , Walport M , etal. Strengthening capacity for health research in Africa. Lancet. 2008; 372: 1590–3.

- Fisher AA , Foreit JR . Designing HIV/AIDS intervention studies: an operations research handbook. 2002; New York, NY: Population Council.

- Zachariah R , Ford N , Philips M , Lynch S , Massaquoi M , Janssens V , etal. Task shifting in HIV/AIDS: opportunities, challenges and proposed actions for sub-Saharan Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009; 103: 549–58.