Abstract

Background

In Uganda, health system challenges limit access to good quality healthcare and contribute to slow progress on malaria control. We developed a complex intervention (PRIME), which was designed to improve quality of care for malaria at public health centres.

Objective

Responding to calls for increased transparency, we describe the PRIME intervention's design process, rationale, and final content and reflect on the choices and challenges encountered during the design of this complex intervention.

Design

To develop the intervention, we followed a multistep approach, including the following: 1) formative research to identify intervention target areas and objectives; 2) prioritization of intervention components; 3) review of relevant evidence; 4) development of intervention components; 5) piloting and refinement of workshop modules; and 6) consolidation of the PRIME intervention theories of change to articulate why and how the intervention was hypothesized to produce desired outcomes. We aimed to develop an intervention that was evidence-based, grounded in theory, and appropriate for the study context; could be evaluated within a randomized controlled trial; and had the potential to be scaled up sustainably.

Results

The process of developing the PRIME intervention package was lengthy and dynamic. The final intervention package consisted of four components: 1) training in fever case management and use of rapid diagnostic tests for malaria (mRDTs); 2) workshops in health centre management; 3) workshops in patient-centred services; and 4) provision of mRDTs and antimalarials when stocks ran low.

Conclusions

The slow and iterative process of intervention design contrasted with the continually shifting study context. We highlight the considerations and choices made at each design stage, discussing elements we included and why, as well as those that were ultimately excluded. Reflection on and reporting of ‘behind the scenes’ accounts of intervention design may improve the design, assessment, and generalizability of complex interventions and their evaluations.

To access the supplementary material for this article, please see Supplementary files under ‘Article Tools’

Good quality healthcare for malaria includes accurate diagnosis of suspected malaria cases and provision of prompt, effective treatment with artemisinin combination therapies (ACT) (Citation1); however, in Uganda and elsewhere, health system challenges often limit access to good quality care and contribute to slow progress on malaria control (Citation2–Citation4). In Uganda, good quality care has been described as appropriate clinical processes combined with respectful interpersonal interactions and adequate resources (Citation5). Benefits of providing good quality care include increased demand for services (Citation6–Citation8), improved attendance at health centres (Citation9), better relationships between patients and health workers (Citation10), and increased clinic loyalty (Citation11), potentially producing better health outcomes (Citation12). Interventions are urgently needed to improve the quality of care provided at health centres, increase patient attendance, and ultimately improve health outcomes for malaria and other illnesses (Citation13, Citation14). However, the optimal approach to improving quality of care is not clear, particularly in low-resource settings (Citation15). Provision of basic training and health education have been tried, but appear to have limited impact, prompting calls for more complex interventions targeting the multidimensional nature of patient treatment seeking (Citation16) and provider practices (Citation17, Citation18).

For the PRIME trial (Citation19), we developed a complex intervention targeting malaria case management at public health centres in Uganda. Drawing on the available literature (Citation20, Citation21), we aimed to design an intervention that was evidence-based and grounded in theory, was tailored to our study setting, could be evaluated within a randomized controlled trial, and had the potential to be scaled up sustainably by the Ugandan Ministry of Health. The final PRIME intervention consisted of four components: 1) training in fever case management and use of rapid diagnostic tests for malaria (mRDTs); 2) workshops in health centre management (HCM); 3) workshops in patient-centred services (PCS); and 4) ensuring the supply of mRDTs and artemether–lumefantrine (AL, the first-line ACT for malaria in Uganda). The primary outcome for the evaluation of the PRIME intervention was the prevalence of anaemia (haemoglobin <11.0 g/dL) in individual children under five measured in annual surveys of communities surrounding health centres enrolled in the PRIME trial (Citation19).

Interventions such as PRIME can be considered complex due to their multiple, interacting components, which address multifaceted problems within dynamic systems (Citation22, Citation23). Responding to calls for more detailed and transparent reporting of intervention components (Citation24–Citation26) and designs (Citation27, Citation28), here we describe the process of designing the PRIME intervention, including the choices we made and the challenges we faced, and how this shaped the final intervention package.

Study setting

The PRIME intervention was designed for Tororo, Uganda, an area of high malaria transmission (Citation29). In both health centres and communities, infrastructure is limited. Health centres are generally run by nurses or nursing assistants; many lack electricity, running water, functioning laboratories, and adequate staffing. As a result of system-wide reforms in the 1990s and early 2000s, public healthcare was decentralized and, in theory, provided free of charge (Citation30). Due to frequent stock-outs of essential drugs, including antimalarials, patients were often forced to purchase drugs or go without adequate treatment (Citation31).

Intervention development

In developing the intervention, we followed a step-wise approach informed by the literature (Citation22, Citation32) (Citation33), including the following: 1) formative research to identify target areas and refine objectives; 2) prioritization of intervention components; 3) review of relevant evidence to support intervention content; 4) development of intervention components; 5) piloting and refinement; and 6) consolidation of the PRIME intervention theories of change.

Step 1. Formative research to identify target areas and refine objectives

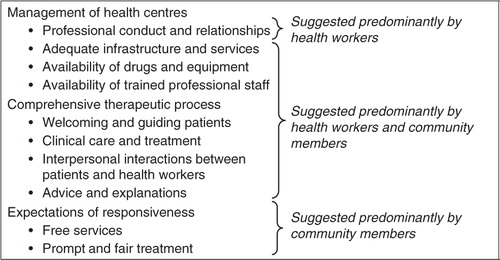

In 2009–2010, we conducted mixed methods research to characterize the population and local health services using a household survey, situational analysis of government-run health centres, and qualitative assessment of health workers’ and community members’ experiences at health centres (Citation34). Through an iterative thematic analysis, we identified aspirations for good quality care and malaria case management and suggestions of how these might be achieved. Health workers and community members shared ideals of what constituted good care, suggesting that patients might be attracted to attend health centres if quality of care was improved (). However, multiple challenges were identified, including lack of equipment and basic infrastructure, high patient-to-staff ratios, poor health centre management, and stock-outs of antimalarials and other drugs. Social challenges were also identified, including low health worker motivation and difficult relationships between health workers and community members due to lack of trust, language barriers, discriminatory behaviours, and requests for informal payments for services.

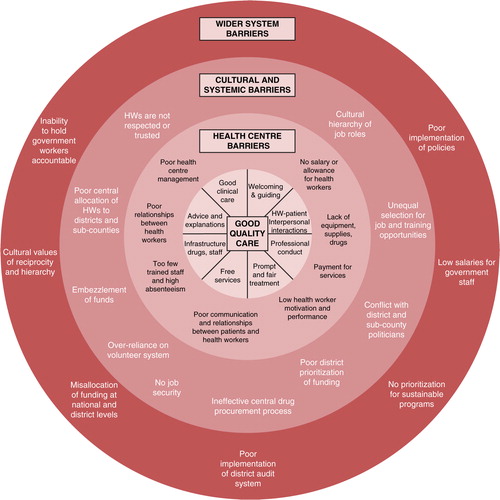

We categorized the challenges identified, including health centre factors, cultural and systemic issues, and wider system factors. The results of our analysis identified eight key components of good quality care and corresponding target areas for potential intervention (). Through this process, we differentiated challenges that were amenable to implementation research from those that were beyond the project's scope, thereby reducing a range of complex challenges into a definable set of factors for action at health centres.

Step 2. Prioritization of intervention components

Prioritizing components to include in the PRIME intervention was an iterative process. We conducted a workshop and follow-up meetings with stakeholders involved in malaria control and child health programmes, including researchers and programme officers at the Ministry of Health, the National Malaria Control Programme, Makerere University, and a local malaria-related non-governmental organization. Together, we reviewed the findings of the formative research and prioritized potential interventions based on stakeholders’ guidance. Overall, stakeholders agreed that we should target malaria case management, patient-centred care, and HCM. However, some of the activities we proposed were deemed beyond the scope of our project. For example, to address staffing shortages and absenteeism, we suggested negotiating with district officials to increase salaries and hire additional staff. We also suggested supplementing the primary healthcare fund – a small cash fund provided to health centre in-charges (often erratically) to pay for essential activities, including transportation of drugs, cleaning services, and necessary supplies. However, district officials were against these propositions, arguing that they would be difficult to administer and sustain. outlines further details of these and other activities that were removed from consideration during this process.

Table 1 Activities considered but excluded as out of scope for the PRIME intervention

Through this process of prioritization we arrived at four intervention components (, Supplementary file 1), including the following: 1) training in fever case management and use of mRDTs (FCM); 2) workshops in HCM; 3) workshops in PCS; and 4) supporting the supply of mRDTs and AL.

Table 2 PRIME training and workshop modules

Step 3. Review of relevant evidence to support intervention content

We searched for existing training packages in the published and grey literature, both online and in local library collections, prioritizing interventions that had been evaluated and found to be effective in Uganda or similar low-resource contexts.

FCM module

For the FCM module, we identified a training package developed by the Joint Uganda Malaria Training Program (JUMP) team, utilizing mRDT training guidelines and job aids adopted by Uganda's Ministry of Health (Citation35). The training consists of lectures and practical sessions, followed by three rounds of support supervision by the JUMP team on-site at health centres (at 1 week, 6 weeks, and 6 months post-training). The training has been shown to improve fever case management and reduce the number of unnecessary antimalarial treatments when implemented in public health centres in Uganda (Hopkins, unpublished observations) (Citation36).

HCM and PCS modules

For the HCM and PCS modules, we were unable to identify suitable pre-existing interventions. Although interpersonal interactions between health workers and patients are considered to be central to good quality care (Citation5, Citation13) (Citation37, Citation38), the philosophy of PCS is not as prominent in African healthcare (Citation39) as it is elsewhere (Citation40, Citation41). In addition, most HCM interventions we identified were large-scale and implemented in a top-down format. The Securing Uganda's Right to Essential Medicines (SURE) programme is an example (42; see also Refs. (Citation43–Citation47). Because rigorous evaluations of these programmes have been limited, there was little evidence to inform the PRIME intervention. Thus, we opted to design the HCM and PCS modules ourselves.

Our HCM and PCS modules are based on concepts and resources originally developed by AH for a health-provider communication training model in collaboration with health providers in seven countries in Eastern Europe and Africa and with the Kenya Medical Research Institute/Wellcome Trust Research Programme (Haaland, personal communication, 15 May 2010). The HCM modules were designed to align with existing HCM processes. For the PCS modules, we aimed to strengthen providers’ relationships with patients, colleagues, and the community (Citation38), by reorienting the care-seeking experience towards patients’ aspirations for good quality care (Citation5).

Supply of mRDTs and AL

We aimed to align the PRIME supply component with Uganda's existing supply system and the SURE programme (Citation42). However, while we were developing the intervention, Uganda's National Medical Stores (NMS) distribution system changed from a ‘pull’ system, in which drugs were ordered by health centres, to a ‘push’ system, with regular delivery of a pre-determined package of drugs, requiring us to revise the PRIME supply component. We identified an existing health worker to act as a liaison, who was responsible for gathering stock information from health centres and facilitating delivery of mRDTs and AL from PRIME when the NMS supply was inadequate or failed. The SURE programme, introduced in 2009, aimed to gather drug stock information and minimize stock-outs through supervision visits. The PRIME intervention utilized SURE's pharmaceutical management information system forms and procedures.

Step 4. Development of intervention components: HCM and PCS modules

To develop the HCM and PCS modules, we reviewed evidence on successful intervention activities; translated evidence into content; incorporated behaviour change theory, adult learning cycles, and learning activities; and created workshop manuals.

Reviewing evidence on successful intervention activities

We reviewed the literature to identify activities targeting health worker communication and interpersonal relationships, patient satisfaction, health worker supervision and coaching, and management of health centres. We focused on low-cost and low-resource interventions, prioritizing interventions that had been successfully implemented and evaluated. The review methods are described elsewhere (Chandler, unpublished observations).

Several activities have been shown to improve communication between health workers and community members, producing a positive effect on patient satisfaction and health outcomes. These activities include enabling clinicians to give patients time to talk during a consultation by asking good questions (Citation48) and employing active listening (Citation49, Citation50) to elicit better information from patients (Citation51). Activities to build rapport and support emotional care by reassuring patients (Citation52) have also been shown to facilitate patients’ therapeutic reactions (Citation53–Citation55). Likewise, activities promoting ‘positive communication’ may improve teamwork by recognizing how personal circumstances and work environment affects emotions and communication (Citation52, Citation56). Activities to improve relationships between health workers include building self-awareness and constructive communication through vignettes, which are used to identify and resolve sources of conflict (Citation57). Notably, of these activities, only ‘time to talk’ was drawn from a low-income setting.

Activities shown to improve patient satisfaction with experiences at health centres include greeting patients (Citation58) and guiding patients through the health centre (Citation46). Interventions promoting supervision and coaching were also identified, although evidence that these activities change provider performance was weak (Citation59, Citation60). We also considered health worker performance management programmes, including the SURE programme and the Uganda Malaria Surveillance Programme's (UMSP) Continuous Quality Improvement Project, which demonstrated that providing health status reports and regular supervision with constructive feedback improved health worker performance (Mpimbaza, personal communication, 10 June 2010). However, the UMSP activities had not been systematically evaluated. Thus, we were forced to weigh the available evidence and decide which activities best informed the design of our intervention package. We ultimately chose not to include coaching or supervision due to the concerns about sustainability, both during the trial and if scaled up, and the limited evidence base supporting coaching and supervision in our setting (Citation61, Citation62).

Developing intervention content

For drug supply management, we drew on the literature to develop the ACT Drug Distribution Assessment Tool, a one-page tool to support health workers in resolving everyday distribution bottlenecks that are not tracked in standard monitoring tools, but are often the cause of health centre drug stock-outs (Citation63). For financial management, we developed the Primary Health Care Fund Budgeting and Accounting Tool, a one-page tool to assist health workers with managing the health centre primary healthcare fund.

For the PCS modules, we adapted activities to improve health worker communication developed mainly in high-income settings to our study setting by using local cultural and social references drawn from our formative research. We deconstructed concepts contained in activities such as giving time to talk, building rapport and emotional care, and self-awareness and reconstituted these in forms and definitions meaningful to the study context. Thus, activities maintained their intended purpose but were communicated using scenarios and discussion points relevant to health workers’ everyday experiences.

Incorporating behaviour change theory

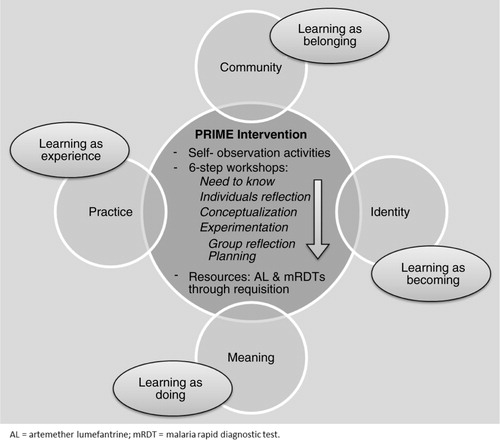

The HCM and PCS modules are underpinned by behaviour change theory to initiate the intended pathway of effect. Both modules aimed to build a supportive community of practice. The Communities of Practice behaviour change theory posits a cyclical process of change, where individuals’ frames of reference are transformed through participation in a community of peers, and their participation in turn transforms the community (Citation64). This process serves to create an ‘informal curriculum’ for health workers in addition to the existing overarching core curricula (Citation65). Through this process, learners engage with other community members and reflect critically on their practice through a social process of individual and collective learning (Citation66).

The theory of Communities of Practice resonated in our setting where many health workers learn primarily on the job. Likewise, our setting lacks many external motivators that have been shown to promote health worker performance, such as financial incentives, constructive supervision, professional accreditation, and opportunities for promotion (Citation67–Citation71). Therefore, we sought to balance the limitations of the context with the opportunity to stimulate health workers’ internal motivations for providing good quality care (Citation72), which included the desire to be viewed as professional, to be respected by colleagues and community members, and to be valued for providing good healthcare services (Citation34). We theorized that, as health workers built, demonstrated, and received positive feedback on their clinical, interpersonal, and managerial skills, the social processes emerging from participation in the community of practice would help them to develop their professional identity and sustain positive skills and behaviours (Citation73).

Incorporating an adult learning cycle and learning activities

The HCM and PCS modules were designed as interactive weekly 3-hour workshops to promote group learning, contributing to the development of a community of practice. The structure was designed to allow time to reflect and practice skills in between workshops and to get feedback at subsequent workshops. Small groups of health workers were selected to enhance participation and encourage peer support in the future. The workshops were led by three members of the PRIME research team, who had medical backgrounds but little experience in interactive training methods, as is the norm in Uganda (Citation74).

The workshops were framed as continuing professional development with interactive learning activities which have been shown to improve health worker knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviours leading to improved patient outcomes (Citation75–Citation77). The workshops were structured as a six-step adult learning cycle drawn from Kolb's (Citation78) experiential learning theory, which includes four stages: experience, reflection, conceptualization, and planning; and from Knowles’ (Citation79) theory of adult learning, which asserts that adults must first establish why they should learn something before proceeding to acquiring new knowledge. The six steps involve developing a ‘need to know’, individual reflection, conceptualization, experimentation, group reflection, and planning. To activate this learning cycle, the workshops employ a variety of participatory learning methods drawn from training modules in similar contexts (Supplementary file 2) (Haaland, personal communication, 15 May 2010) (Citation37, Citation48).

The PCS module also included weekly self-observation activities (SOA) that aimed to stimulate learners’ purposeful critical analysis of their knowledge and experience (Citation80), enabling them to engage and deal with their emotions (Citation81) and develop appreciation and respect for others (Citation82). Semi-structured SOAs followed by feedback in groups provided opportunities for both individual learning and change as a community (Citation66). The SOAs were adapted from tasks designed and tested in a number of other healthcare settings (Haaland, personal communication, 15 May 2010) (Citation48).

Creation of Workshop Manuals

For each HCM and PCS workshop, we created corresponding trainer and learner manuals – 18 in total (Supplementary file 2). We contracted with an experienced public health consulting firm (Citation83) to fine-tune the learning activities and typeset the manuals. This was a collaborative effort, requiring significant input on a new layer of design considerations, including the colours and fonts that would best communicate the ethos of the workshops and how pictures and layout of activities could support learning retention. We also considered how the trainer instructions would encourage active facilitation but also support trainers in drawing out learners’ reflections and experiences.

Step 5. Piloting and refinement: HCM and PCS modules

We conducted two rounds of piloting the HCM and PCS modules with 10 health workers from outside of the study area. We administered questionnaires to learners and trainers, gathered daily feedback from trainers and the piloting team, and conducted focus group discussions with participants at the end of the modules. The piloting evaluated the relevance and applicability of the learning objectives and content, as well as the delivery of the training (Citation84). The piloting proved to be an invaluable exercise, unexpectedly revealing that the learning capacity of our intended learners was not in line with our expectations. Whereas the six-step learning process and interactive activities appeared to support learning, some of the module concepts and language were too advanced, requiring us to readjust our expectations of how these concepts could be feasibly introduced. The trainers, who had more experience with didactic approaches, also reported challenges with the interactive format of the manuals. Thus, we revised the modules, aiming to ‘hit the mark’ with our intended learners by simplifying the language, reducing the number of new concepts and learning objectives per module, including more interactive activities, and revising the prompts and instructions throughout the trainers’ manuals. See for examples of revisions made. The second round of piloting indicated that the revised modules did meet our intended objectives. However, the piloting and subsequent revisions added significant and unexpected delays to the design process. The final learning objectives are in Supplementary file 1, and final versions of the modules can be found online (Citation85).

Table 3 Example of revisions made to the PCS and HCM modules as a result of piloting

Step 6. Consolidation of the PRIME intervention theories of change

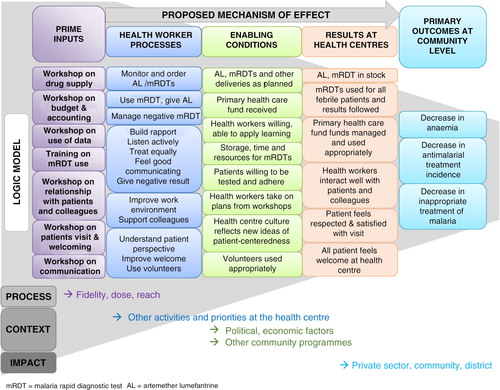

Drawing on complex intervention design and evaluation guidance (Citation22, Citation86–Citation88), we articulated two complementary intervention theories – a programme theory and an implementation theory. These theories make explicit how and why we hypothesized the PRIME intervention components would combine to produce desired outcomes (Citation89). The programme theory, represented in a logic model (), describes why the four intervention components are anticipated to produce specific outcomes. It hypothesizes that an intervention addressing the barriers to providing good quality care for malaria and febrile illnesses will improve appropriate malaria case management and patient satisfaction, leading to repeat attendance at health centres, and ultimately, improved health outcomes in community children. The implementation theory () articulates how the intervention will stimulate behaviour change. It hypothesizes that a learning process stimulating health workers’ cognitive, emotional, and social learning processes through interactive workshops reinforced within a community of practice will lead to immediate and sustained change in health worker motivation, behaviour, and practice for providing good quality care.

Discussion

We designed a complex intervention targeting delivery of care for malaria at public health centres in Uganda (Citation19, Citation90). Informed by best practice, we aimed to develop an intervention that was evidence-based, grounded in theory, and appropriate for our study setting using a systematic approach. In the process, we learned several important lessons related to the scope of the intervention and necessary compromises, the tension between static interventions and dynamic contexts, and the challenges of rigorously designing a behaviour change intervention for low-resource settings. By transparently reporting our ‘behind the scenes’ accounts, we hope to inform the design and content of future complex interventions.

Our formative research identified several challenges to providing good quality care at different levels of the health system. Many of these challenges were interpreted to be rooted in wider health system norms that prioritize technical skills and technologies over a patient-centred approach to care. Likewise, our context is characterized by ineffective political systems and a deeply embedded hierarchical structure that perpetuates power imbalances throughout the health system (Citation5). In an attempt to define factors for action at the health centre level, we found it necessary to bracket out much of the complexity and the political–economic reality underlying health service provision in Uganda. As a result, we focused on intervention components that had the highest likelihood of success and buy-in from stakeholders within the constraints of a focused project, which others have noted as a critical factor for success when designing health service interventions (Citation91). However, this choice meant that the deeper social, political, and economic challenges that underlie poor healthcare quality and lack of progress on malaria remained unaddressed by our intervention (Citation92). Rather than ignore these challenges as being out of the scope of the intervention design process, engaging with them was required to situate the intervention within the wider health system context and to provide deeper insight into how the intervention components might operate within this system. Recognizing that interventions are a part of complex health systems (Citation23), we urge intervention designers to consider and report on the process of negotiating wider social, political, and economic realities and how this influenced intervention content and design.

The slow and iterative process of intervention design contrasted with the continually shifting study context. During the intervention design process, which took almost 1 year, several changes occurred in the study context that had significant impacts on the intervention. The integration of the SURE programme and implementation of NMS's push delivery system required a reconceptualization of the HCM modules and the supply component. A policy introduced by the District Health Office to remove untrained volunteers from health centres required an adaptation of the PCS module to suit other authorized support staff. This ever-changing context created a ‘moving target’ with which to align the intervention and contrasted with the need to develop standardized content suitable for evaluation in a cluster-randomized trial. To accommodate this situation, the modules were designed as a structured framework complemented by reflective learning activities to engage with learners’ everyday experiences. In this way, the structure of the modules was standardized and reproducible, but the learning points could be adapted to the local context (Citation93). While the challenge of implementing and evaluating static interventions in dynamic contexts has been considered (Citation94–Citation97), we encountered similar tensions during intervention design. To resolve these issues, flexibility and responsiveness were needed. Although this required additional investments of time and resources, we found this was essential to designing an intervention appropriate for our study setting.

Developing the PRIME intervention required a diversity of expertise, including clinicians, social scientists, epidemiologists, health workers, project managers, and training consultants. Team members approached the design of the intervention from different epistemological and disciplinary backgrounds. Developing the logic model suited the positivist perspective favouring a representation of the intervention as discrete components leading to predefined measurable outcomes. The process of developing the logic model provided an opportunity for the team to share and consolidate ideas and emerged as a convenient communication tool. However, the static nature of the model did not adequately capture the way we expected change to occur, recognizing that change processes would be dynamic, emergent, and contingent on links between the intervention, individuals, and society (Citation98). By utilizing both text and visual models as part of our intervention theories, we endeavoured to articulate a specific intervention theory while acknowledging that the intervention would be enacted in a dynamic context, which would create many unique change processes, both intended and unintended. Our different disciplinary perspectives also led us to engage with questions of what the intervention ‘is’ – for example, rather than simply a composition of training materials and events, we began to conceive it as a series of interactions embedded in social relationships through which its meaning would emerge. This raised the possibility that the meaning of the intervention could be constructed differently by different actors, which was important to capture in our evaluation activities. Our experience concurs that an interdisciplinary approach appears to be essential for making meaningful progress towards improving population health (Citation99); however, it should be recognized that this approach is time- and resource-intensive (Citation91, Citation100) (Citation101), requiring concerted effort to align perspectives into a shared understanding of the intervention (Citation102).

Our experience designing the PRIME intervention reflected a process that is more interactive and demanding than the available evidence and theory suggest (Citation20). While the literature guiding intervention design is expanding (Citation91, Citation103), few authors discuss the construction process we found necessary to reach the final intervention package. The importance of reporting ‘insider accounts’ of intervention implementation and evaluation activities to better interpret trial outcomes has been noted (Citation104, Citation105). We argue that this same reflective and transparent reporting practice should apply to intervention design. Guidelines for reporting complex intervention content ask authors to describe the reasons for selecting intervention components, which may include ‘experience of or evidence on the suitability of the component to achieve the intended change process’ (4: (Citation106). Our experiences revealed manifold reasons influencing the processes through which intervention content was considered, shaped, and integrated (or discarded), in light of research aims, available evidence, and resource constraints. Sharing accounts of activities that were considered but omitted, and why these decisions were made, may be as informative as descriptions of final intervention packages. Thus, we argue that describing these behind-the-scenes accounts of the intervention design process should be considered a key ‘experience’ included in guidelines for reporting intervention content and their evaluations. A reflective and transparent reporting of the design process may promote assessments of the intervention's internal validity, facilitate interpretation and generalizability of results, and inform future interventions. As complex interventions gain momentum in healthcare, guidelines for developing interventions and reporting on the design process will need to evolve, consistent with current debates of how complex interventions should be conceptualized and evaluated (Citation23, Citation98) (Citation107).

Authors' contributions

DDD, CIRC, and SGS conceived of the paper. DDD, CIRC, and SGS designed the intervention with support from AH, FN, LT, SN, CMS, and MK. DDD drafted the paper. All authors revised the manuscript critically and approved the final version for publication.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest and funding.

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (187.9 KB)Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all members of the PRIME trial and PROCESS study teams at the Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration, Uganda. DDD is funded by the UK Economic and Social Research Council's Bloomsbury Doctoral Training Centre. The PRIME intervention design project and evaluation studies are funded by the ACT Consortium through a grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Notes

To access the supplementary material for this article, please see Supplementary files under ‘Article Tools’

References

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. 2010; Geneva: WHO Press. 2nd ed.

- Stratton L, O'Neill MS, Kruk ME, Bell ML. The persistent problem of malaria: addressing the fundamental causes of a global killer. Soc Sci Med. 2008; 67: 854–62.

- Rao VB, Schellenberg D, Ghani AC. Overcoming health systems barriers to successful malaria treatment. Trends Parasitol. 2013; 29: 164–80.

- Yeka A, Gasasira A, Mpimbaza A, Achan J, Nankabirwa J, Nsobya S, etal. Malaria in Uganda: challenges to control on the long road to elimination: I. Epidemiology and current control efforts. Acta Trop. 2012; 121: 184–95.

- Chandler CIR, Kizito J, Taaka L, Nabirye C, Kayendeke M, DiLiberto D, etal. Aspirations for quality health care in Uganda: how do we get there?. Hum Resour Health. 2013; 11: 13.

- El Arifeen S, Blum LS, Hoque DM, Chowdhury EK, Khan R, Black RE, etal. Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) in Bangladesh: early findings from a cluster-randomised study. Lancet. 2004; 364: 1595–602.

- McPake B. User charges for health services in developing countries: a review of the economic literature. Soc Sci Med. 1993; 36: 1397–405.

- Wouters AV. Essential national health research in developing countries: health care financing and the quality of care. Int J Heal Plan Manag. 1991; 6: 253–71.

- Mbaruku G, Bergstrom S. Reducing maternal mortality in Kigoma, Tanzania. Heal Policy Plan. 1995; 10: 71–8.

- Deyo RA, Inui TS. Dropouts and broken appointments. A literature review and agenda for future research. Med Care. 1980; 18: 1146–57.

- Vera H. The client's view of high-quality care in Santiago, Chile. Stud Fam Plan. 1993; 24: 40–9.

- Williams B. Patient satisfaction: a valid concept?. Soc Sci Med. 1994; 38: 509–16.

- Kizito J, Kayendeke M, Nabirye C, Staedke SG, Chandler CI. Improving access to health care for malaria in Africa: a review of literature on what attracts patients. Malar J. 2012; 11: 55.

- World Health Organization. World health report 2008: primary health care– now more than ever. 2008; World Health Report. Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/2008/en/ [cited 15 March 2014]..

- Pariyo GW, Gouws E, Bryce J, Burnham G. Improving facility-based care for sick children in Uganda: training is not enough. Health Policy Plan. 2005; 20(Suppl 1): i58–68.

- Smith LA, Jones C, Meek S, Webster J. Review: provider practice and user behavior interventions to improve prompt and effective treatment of malaria: do we know what works?. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009; 80: 326–35. [PubMed Abstract].

- Grimshaw JM, Shirran L, Thomas R, Mowatt G, Fraser C, Bero L, etal. Changing provider behavior: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions. Med Care. 2001; 39: II2–45.

- Oxman AD, Thomson MA, Davis DA, Haynes RB. No magic bullets: a systematic review of 102 trials of interventions to improve professional practice. Can Med Assoc J. 1995; 153: 1423–31.

- Staedke SG, Chandler CIR, DiLiberto D, Maiteki-Sebuguzi C, Nankya F, Webb E, etal. The PRIME trial protocol: evaluating the impact of an intervention implemented in public health centres on management of malaria and health outcomes of children using a cluster-randomised design in Tororo, Uganda. Implement Sci. 2013; 8: 114.

- Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008; 337: 979–83.

- Campbell M, Fitzpatrick R, Haines A, Kinmonth AL, Sandercock P, Spiegelhalter D, etal. Framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. BMJ. 2000; 321: 694–6.

- Medical Research Council. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: new guidance. 2008; London: Medical Research Council.

- Hawe P, Shiell A, Riley T. Theorising interventions as events in systems. Am J Community Psychol. 2009; 43: 267–76.

- The Improved Clinical Effectiveness through Behavioural Research. Designing theoretically-informed implementation interventions. Implement Sci. 2006; 1: 4. [PubMed CentralFull Text].

- Proctor E, Powell B, McMillen J. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci. 2013; 8: 139.

- Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011; 6: 42.

- Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, etal. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014; 348: g1687.

- Michie S, Fixsen D, Grimshaw J, Eccles M. Specifying and reporting complex behaviour change interventions: the need for a scientific method. Implement Sci. 2009; 4: 40.

- Kamya MR, Arinaitwe E, Wanzira H, Katureebe A, Barusya C, Kigozi SP, etal. Malaria transmission, infection, and disease at three sites with varied transmission intensity in Uganda: implications for malaria control. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015; 92: 903–12.

- Burnham G, Pariyo G, Galiwango E, Wabwire-Mangen F. Discontinuation of cost sharing in Uganda. Bull World Health Organ. 2004; 82: 187–95. [PubMed Abstract] [PubMed CentralFull Text].

- Anokbonggo WW, Ogwal-Okeng JW, Obua C, Aupont O, Ross-Degnan D. Impact of decentralization on health services in Uganda: a look at facility utilization, prescribing and availability of essential drugs. East Afr Med J. 2004 Suppl 2–7.

- Arhinful DK, Das AM, Heggenhougen K, Higginbotham N, Iyun FB, Quick J, etal. How to use applied qualitative methods to design drug use interventions, working draft. 1996; International Network for the Rational Use of Drugs. Available from: http://www.inrud.org/documents/upload/How_to_Use_Applied_Qualitative_Methods.pdf [cited 15 March 2014]..

- Nichter M, Acuin CS, Vargas A. Introducing zinc in a diarrhoeal disease control programme guide to conducting formative research. 2008; 73. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241596473_eng.pdf [cited 15 March 2014]..

- Staedke SG, Uganda Malaria Surveillance Project. Phase 1 report: Tororo district survey project. 2010; Kampala, Uganda: ACT Consortium, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. Characterizing the population and local health services.

- National Malaria Control Program. User's manual: use of rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) for malaria in fever case management in Uganda. 2009; Kampala: National Malaria Control Program.

- Odaga J, Sinclair D, Ja L, Donegan S, Hopkins H, Garner P. Rapid diagnostic tests versus clinical diagnosis for managing people with fever in malaria endemic settings (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 4 008998.

- Haaland A, Vlassoff C. Introducing health workers for change: from transformation theory to health systems in developing countries. Health Policy Plan. 2001; 16(Suppl 1): 1–6.

- Stewart M. Towards a global definition of patient centred care. Br Med J. 2001; 322: 444–5.

- Nayiga S, DiLiberto D, Taaka L, Nabirye C, Haaland A, Staedke SG, etal. Strengthening patient-centred communication in rural Ugandan health centres: a theory-driven evaluation within a cluster randomized trial. Evaluation. 2014; 20: 471–91.

- Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc Sci Med. 2000; 51: 1087–110.

- Balint M. The doctor, his patient and the illness. 1957; Oxford, England: International Universities Press.

- SURE – Securing Ugandans’ Right to Essential Medicines. Securing Ugandans’ Right to Essential Medicines (SURE). Available from: http://www.sure.ug/ [cited 15 March 2014]..

- Benavides BM. Supporting health worker performance with effective supervision. 2009; CA: Chapel Hill. Available from: http://www.intrahealth.org/page/supporting-health-worker-performance-with-effective-supervision [cited 15 March 2014]..

- Shabahang J. Using team problem solving to improve adherence with malaria treatment guidelines in Malawi. 2003; Bethesda, MD Available from: http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/pnacu771.pdf [cited 15 March 2014]..

- Langley G, Moen R, Nolan K, Nolan T, Norman C, Provost L. The improvement guide: a practical approach to enhancing organizational performance. 2009; 2nd ed, San Fransisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- EngenderHealth. A process for improving quality in health services. 2003; New York: EngenderHealth. 1–150.

- Management Sciences for Health. Managers who lead: a handbook for improving health services. 2005; Cambridge, MA: Management Sciences for Health. 294.

- Haaland A, Molyneux CS, Marsh V. Quality information in field research: training manual on practical communication skills for field researchers and project personnel. World Health Organization on behalf of the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases. 2006. Available from: http://www.who.int/tdr/publications/documents/quality_information.pdf?ua=1 [cited 15 March 2014]..

- Fassaert T, van Dulmen S, Schellevis F, Bensing J. Active listening in medical consultations: development of the Active Listening Observation Scale (ALOS-global). Patient Educ Couns. 2007; 68: 258–64.

- Krasner MS, Epstein RM, Beckman H, Suchman AL, Chapman B, Mooney CJ, etal. Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physicians. J Am Med Assoc. 2009; 302: 1284–93.

- Marvel MK, Epstein RM, Flowers K, Beckman HB. Soliciting the patient's agenda – Have we improved?. JAMA. 1999; 281: 283–7.

- Neumann M, Bensing J, Mercer S, Ernstmann N, Ommen O, Pfaff H. Analyzing the “nature” and “specific effectiveness” of clinical empathy: a theoretical overview and contribution towards a theory-based research agenda. Patient Educ Couns. 2009; 74: 339–46.

- Di Blasi Z, Harkness E, Ernst E, Georgiou A, Kleijnen J. Influence of context effects on health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet. 2001; 357: 757–62.

- Leventhal H, Leventhal EA, Contrada RJ. Self-regulation, health, and behavior: a perceptual-cognitive approach. Psychol Health. 1998; 13: 717–33.

- Fassaert T, van Dulmen S, Schellevis F, van der Jagt L, Bensing J. Raising positive expectations helps patients with minor ailments: a cross-sectional study. BMC Fam Pract. 2008; 9: 38.

- Thomas KB. General practice consultations: is there any point in being positive?. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1987; 294: 1200–2.

- Kozub ML, Kozub FM. Dealing with power struggles in clinical and educational settings. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2004; 42: 22–31. [PubMed Abstract].

- Makoul G, Zick A, Green M. An evidence-based perspective on greetings in medical encounters. Arch Intern Med. 2007; 167: 1172–6.

- Bosch-Capblanch X, Garner P. Primary health care supervision in developing countries. Trop Med Int Health. 2008; 13: 369–83.

- Bosch-Capblanch X, Liaqat S, Garner P. Managerial supervision to improve primary health care in low- and middle-income countries (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 9 CD006413.

- Rowe AK, Onikpo F, Lama M, Osterholt DM, Rowe SY, Deming MS. A multifaceted intervention to improve health worker adherence to integrated management of childhood illness guidelines in Benin. Am J Public Health. 2009; 99: 837–46.

- Rowe AK, Onikpo F, Lama M, Deming MS. The rise and fall of supervision in a project designed to strengthen supervision of integrated management of childhood illness in Benin. Health Policy Plan. 2010; 25: 125–34.

- DiLiberto D. The ACT distribution assessment tool: an evaluation tool for assessing the implementation of district level antimalarial drug distribution in Uganda. 2009. MSc Dissertation, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London.

- Wenger E. Communities of practice. Learning, meaning, and identity. 1998; New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Hafferty FW. Beyond curriculum reform: confronting medicine's hidden curriculum. Acad Med. 1998; 73: 403–7.

- Mann KV. Theoretical perspectives in medical education: past experience and future possibilities. Med Educ. 2011; 45: 60–8.

- Chandler CIR, Chonya S, Mtei F, Reyburn H, Whitty CJM. Motivation, money and respect: a mixed-method study of Tanzanian non-physician clinicians. Soc Sci Med. 2009; 68: 2078–88.

- Sodhi S, Banda H, Kathyola D, Joshua M, Richardson F, Mah E, etal. Supporting middle-cadre health care workers in Malawi: lessons learned during implementation of the PALM PLUS package. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014; 14(Suppl 1): S8.

- Dieleman M, Toonen J, Toure H, Martineau T. The match between motivation and performance management of health sector workers in Mali. Hum Resour Health. 2006; 4: 2.

- Mathauer I, Imhoff I. Health worker motivation in Africa: the role of non-financial incentives and human resource management tools. Hum Resour Health. 2006; 4: 24.

- Willis-Shattuck M, Bidwell P, Thomas S, Wyness L, Blaauw D, Ditlopo P. Motivation and retention of health workers in developing countries: a systematic review. BMC Heal Serv Res. 2008; 8: 247.

- Franco LM, Bennett S, Kanfer R. Health sector reform and public sector health worker motivation: a conceptual framework. Soc Sci Med. 2002; 54: 1255–66.

- Lingard L, Schryer C, Garwood K, Spafford M. “Talking the talk”: school and workplace genre tension in clerkship case presentations. Med Educ. 2003; 37: 612–20.

- Ssekabira U, Bukirwa H, Hopkins H, Namagembe A, Weaver MR, Sebuyira LM, etal. Improved malaria case management after integrated team-based training of health care workers in Uganda. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008; 79: 826–33. [PubMed Abstract].

- Robertson MK, Umble KE, Cervero RM. Impact studies in continuing education for health professions: update. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2003; 23: 146–56.

- Mansouri M, Lockyer J. A meta-analysis of continuing medical education effectiveness. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2007; 27: 6–15.

- Forsetlund L, Bjørndal A, Rashidian A, Jamtvedt G, Ma OB, Wolf F, etal. Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 2 CD003030.

- Kolb DA. Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. 1984; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Knowles MS, Holton EF, Swanson RA. The adult learner: the definitive classic in adult education and human resource development. 2005; Burlington, MA: Elsevier. 378. 6th ed.

- Schön DA. The reflective practitioner: how professionals think in action. 1983; New York: Basic Books.

- Lewin K. Field theory in social science: selected theoretical papers. 1951; New York: Harper. Cartwright D, ed.

- Branch WT. Viewpoint: teaching respect for patients. Acad Med. 2006; 81: 463–7.

- WellSense. WellSense – International Public Health Consultants. Available from: http://www.wellsense-iphc.com/ [cited 15 March 2014]..

- Haaland A. Reporting with pictures. A concept paper for researchers and health policy decision-makers. 2001; Geneva: UNDP.

- Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration & ACT Consortium. The ACT PRIME Trainer and Learner Manuals. London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. 2011. Available from: http://www.actconsortium.org/publications.php/12/prime-trainer-and-learner-manuals [cited 10 March 2014]..

- Weiss CH, Connell JP, Kubisch AC, Schorr LB, Weiss CH. Nothing as practical as good theory: exploring theory-based evaluation for comprehensive community initiatives for children and families. 1995; Washington, DC: The Aspen Institute. 238. New approaches to evaluating community initiatives: volume 1, concepts, methods and contexts.

- Judge K, Bauld L. Strong theory, flexible methods: evaluating complex community-based initiatives. Crit Public Health. 2001; 11: 19–38.

- White H. Theory-based impact evaluation: principles and practice. J Dev Eff. 2009; 1: 271–84.

- Weiss CH. Evaluation: methods for studying programs and policies. 1998; 2nd ed, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Chandler CIR, DiLiberto D, Nayiga S, Taaka L, Nabirye C, Kayendeke M, etal. The PROCESS study: a protocol to evaluate the implementation, mechanisms of effect and context of an intervention to enhance public health centres in Tororo, Uganda. Implement Sci. 2013; 8: 113.

- English M. Designing a theory-informed, contextually appropriate intervention strategy to improve delivery of paediatric services in Kenyan hospitals. Implement Sci. 2013; 8: 39.

- Okwaro FM, Chandler CIR, Hutchinson E, Nabirye C, Taaka L, Kayendeke M, etal. Challenging logics of complex intervention trials: community perspectives of a health care improvement intervention in rural Uganda. Soc Sci Med. 2015; 131: 10–17.

- Hawe P, Shiell A, Riley T. Complex interventions: how “out of control” can a randomised controlled trial be?. BMJ. 2004; 328: 1561–3.

- Vahedi Nikbakht-Van de Sande CV, Braat C, Visser AP, Delnoij DM, van Staa AL. Why a carefully designed, nurse-led intervention failed to meet expectations: the case of the Care Programme for Palliative Radiotherapy. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2014; 18: 151–8.

- Hoddinott P, Britten J, Pill R. Why do interventions work in some places and not others: a breastfeeding support group trial. Soc Sci Med. 2010; 70: 769–78.

- Kok MO, Vaandrager L, Bal R, Schuit J. Practitioner opinions on health promotion interventions that work: opening the “black box” of a linear evidence-based approach. Soc Sci Med. 2012; 74: 715–23.

- Bird L, Arthur A, Cox K. “Did the trial kill the intervention?” experiences from the development, implementation and evaluation of a complex intervention. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011; 11: 24.

- Cohn S, Bunn C, Stronge P, Clinch M. Entangled complexity: why complex interventions are just not complicated enough. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2013; 18: 40–3.

- Dean K, Hunter D. New directions for health: towards a knowledge base for public health action. Soc Sci Med. 1996; 42: 745–50.

- Chandler CI, Meta J, Ponzo C, Nasuwa F, Kessy J, Mbakilwa H, etal. The development of behaviour change interventions to support the use of malaria rapid diagnostic tests by Tanzanian clinicians. Implement Sci. 2014; 9: 83.

- Achonduh OA, Mbacham WF, Mangham-Jefferies L, Cundill B, Chandler C, Pamen-Ngako J, etal. Designing and implementing interventions to change clinicians’ practice in the management of uncomplicated malaria: lessons from Cameroon. Malar J. 2014; 13: 204.

- Clarke D, Hawkins R, Sadler E, Harding G, Forster A, McKevitt C, etal. Interdisciplinary health research: perspectives from a process evaluation research team. Qual Prim Care. 2012; 20: 179–89. [PubMed Abstract].

- Nutley T, Gnassou L, Traore M, Bosso AE, Mullen S. Moving data off the shelf and into action: an intervention to improve data-informed decision making in Cote d'Ivoire. Glob Health Action. 2014; 7 25035, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/gha.v7.25035 .

- Wells M, Williams B, Treweek S, Coyle J, Taylor J. Intervention description is not enough: evidence from an in-depth multiple case study on the untold role and impact of context in randomised controlled trials of seven complex interventions. Trials. 2012; 13: 95.

- Reynolds J, DiLiberto D, Mangham-Jefferies L, Ansah EK, Lal S, Mbakilwa H, etal. The practice of “doing” evaluation: lessons learned from nine complex intervention trials in action. Implement Sci. 2014; 9: 75.

- Möhler R, Köpke S, Meyer G. Criteria for reporting the development and evaluation of complex interventions in healthcare: revised guideline (CReDECI 2). Trials. 2015; 16: 1–9.

- Petticrew M. When are complex interventions “complex”? When are simple interventions “simple”?. Eur J Public Health. 2011; 21: 397–8.