Abstract

Background

Although observational data show social characteristics such as gender or socio-economic status to be strong predictors of health, their impact is seldom investigated in randomised controlled studies (RCTs).

Objective & design

Using a random sample of recent RCTs from high-impact journals, we examined how the most often recorded social characteristic, sex/gender, is considered in design, analysis, and interpretation. Of 712 RCTs published from September 2008 to 31 December 2013 in the Annals of Internal Medicine, British Medical Journal, Lancet, Canadian Medical Association Journal, or New England Journal of Medicine, we randomly selected 57 to analyse funding, methods, number of centres, documentation of social circumstances, inclusion/exclusion criteria, proportions of women/men, and reporting about sex/gender in analyses and discussion.

Results

Participants’ sex was recorded in most studies (52/57). Thirty-nine percent included men and women approximately equally. Overrepresentation of men in 43% of studies without explicit exclusions for women suggested interference in selection processes. The minority of studies that did analyse sex/gender differences (22%) did not discuss or reflect upon these, or dismissed significant findings. Two studies reinforced traditional beliefs about women's roles, finding no impact of breastfeeding on infant health but nevertheless reporting possible benefits. Questionable methods such as changing protocols mid-study, having undefined exclusion criteria, allowing local researchers to remove participants from studies, and suggesting possible benefit where none was found were evident, particularly in industry-funded research.

Conclusions

Social characteristics like sex/gender remain hidden from analyses and interpretation in RCTs, with loss of information and embedding of error all along the path from design to interpretation, and therefore, to uptake in clinical practice. Our results suggest that to broaden external validity, in particular, more refined trial designs and analyses that account for sex/gender and other social characteristics are needed.

Introduction

Randomised controlled trials are thought to provide the strongest research evidence of clinical potential or efficacy for medical interventions. By randomly assigning subjects to intervention and control groups both the characteristics of interest but also those that are unidentified should be equally distributed across study arms, allowing researchers to eliminate the effect of individual and social characteristics not being studied.

To examine rather than control for the impact of social traits on health outcomes requires a very different approach. Socio-economic status (SES), race/ethnicity, sex/gender, or social connectedness, for example, must then be measured and considered as independent covariates that alter health outcomes. In reality social traits are not independent but act interdependently to shape opportunities and constraints that may alter gene expression, risk, compliance, access to care, and pathways from exposure to illness (Citation1, Citation2). Study protocols and inclusion criteria should be designed accordingly with enrolment that is large enough to allow for disaggregated analyses of, for example, results for women and men. The strength of randomisation is that baseline although not necessarily static social determinants will be equally distributed and eliminated as sources of bias, while researchers manipulate or control exposures of interest. The weakness is that unless they are managed as variables for analysis the very real impact of those social circumstances on the study endpoint, and interactions with the intervention of interest are hidden. Resulting study findings will then speak only of efficacy in a population cleansed of personal traits and social circumstances, but not of effectiveness and external validity in the real world where no one is devoid of such characteristics as sex/gender or SES.

Lifetime fluctuations in and the social nature of circumstances like SES are readily apparent; however, placing sex and gender among these may require explanation. Sex and gender are two separate but intertwined terms used for categorisation and analyses of men and women. Sex refers to biological attributes and is primarily associated with physical and physiological features, including chromosomes, hormone function, and sexual anatomy. Gender goes beyond biology and refers to the socially constructed roles, behaviours, expressions, and identities of girls, women, boys, men, and gender diverse people. It influences how people perceive themselves and each other, how they act and interact, and the distribution of power and resources in society. Gender is not static and not something a person possesses, it is rather an activity. The concept of ‘doing gender’ manifests this. Doing gender most often incorporates, but can also challenge explicit and implicit social norms, constraints, and expectations that alter ways of behaving and acting as men and women (Citation3–Citation5). Like SES, gender will vary across settings and over time. Although the impact of a group or society's gender norms is not ubiquitous or homogeneous, there are commonalities arising from the experience of being, for example, a woman within a given grouping. Furthermore, like SES, gender can, although it does not always, affect health and wellbeing. For example, in many cultures girls are undervalued relative to boys and are therefore fed less. Similarly, women in many countries are less educated than men, not because of limited individual capacity but because societal and cultural norms imply that higher education is only for men. In countries where women are well educated, or even more educated than men, they are still often under-represented in high-ranked and well-paid jobs, suggesting that gender inequality is not restricted to developing countries but is a worldwide phenomenon. Women currently outlive men globally; however, their longevity advantage has and continues to fluctuate with time and social circumstances (Citation6). This life expectancy difference likely arises from how men and women live their lives, which work and activities they engage in, and risks they are exposed to or take (Citation7–Citation9). Changes in other social circumstances may change the expectations of and roles consigned to men or to women and may accordingly change their doing of gender, illustrating that gender is not a fixed characteristic (Citation5).

In reality, it is seldom possible to isolate sex from gender, as biology interacts with social and environmental living conditions, and sex and gender become tangled together. Genes can be activated or shut down (temporarily or permanently) by environmental factors and ways of living. Since men and women often live different lives with different duties, demands, and resources, this newer epigenetic knowledge contributes to insights about how gender and sex are intertwined. Therefore, using the terms sex and gender has to be done with caution. In this article, we use the term ‘sex-specific’ when talking about diseases or conditions that are restricted to either men or women, like prostate cancer or preterm birth. Gender is used as a separate term when we talk about bias related to being either women or men – because the creation of gender bias is by definition a social process whereby preconceptions and ideas about women and men skew research, investigations, or treatment. Sex or gender are also used as separate terms as the authors of a specific reviewed paper did so. However, we prefer sex/gender as a term that recognises that biology shapes social context which, in turn, shapes biology.

Within a randomly selected sample, exposures being examined may not have uniform or homogeneous effects across social groupings such as sex/gender, race or SES, of study participants (Citation10). If variability is not individual but instead arises from a characteristic of a social subgroup, the statistical independence of participants will be jeopardised. Failure to recognise that subjects may not be independent will introduce error despite randomisation (Citation10). Observational research has demonstrated strong and extensive health effects arising from and associated with membership in the groupings, ‘women’ and ‘men’. Significant sex/gender differences have been well documented with respect to, for example, heart diseases (Citation11) and type 2 diabetes (Citation12). Pharmacokinetics may differ for men and women, as can benefits, side effects, and adverse reactions to drugs (Citation13). Unequal access to medical care for women and men in many settings is of importance in understanding treatment and health outcomes. Finally, gender bias has been demonstrated in clinical decision-making (Citation14, Citation15). Although it does not always alter health, evidence is strong enough to justify considering sex/gender whenever possible, as a modifier of the relationship between intervention and medical outcome (Citation16).

To directly study the impact of any characteristics on a particular outcome in experimental designs requires the ability to randomly allocate these to participants. Although not fixed, social characteristics cannot be randomly assigned. Nevertheless, it is possible to estimate how traits like sex/gender or SES alter outcomes rather than dismissing them as topics not worthy of study in a particular trial. At a minimum, examining interactions of these with independent variables will hint at their effect. Powering a study to enable a priori randomisation of recruited women and men separately so that the study intervention can be examined both within and across these groupings and to assess interactions of social determinants with other variables will increase accuracy and meaning (Citation17–Citation19).

The aim of this systematic sampling review of recent randomised controlled studies (RCTs) is to determine whether and how the social traits of sex/gender are addressed in design, analysis, and interpretation of study findings and to then consider the meanings and impact of the methodologies used. We selected sex/gender for specific examination because the categories ‘man’ and ‘woman’ were the most commonly identified social characteristics in the reviewed RCTs.

Methods

Sample selection

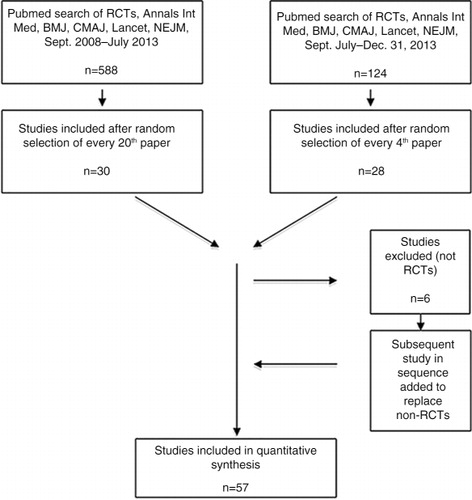

In September 2013, we searched PubMed using the terms randomised controlled trial, clinical trial, human, Annals of Internal Medicine, British Medical Journal, Lancet, Canadian Medical Association Journal, New England Journal of Medicine and the search filters clinical trial, September 2008–1 July 2013. We then sorted the initial 588 papers retrieved by date of publication to randomise papers from each journal and ensure sampling of the entire time frame, and selected every 20th paper for inclusion. In January 2014, a similar search with date limits of July 2013 to 31 December 2013 yielded another 124 papers, of which every fourth paper was selected for review. Recent papers were oversampled to ensure that findings reflected most current research methodology.

When a selected paper was not an RCT (n=6), the next paper on the list was substituted. To establish our analytical method and construct a data extraction template, five studies were reviewed by both researchers, then three more were reviewed independently, and thereafter discussed for concordance of data extraction. After each reviewing another 10 and 9 studies, respectively, both authors again checked for inter-reviewer consistency in approach, information extraction, and interpretation of findings, then reviewed 30 more papers (15 each) independently. All in all, 57 papers were included in the analysis. Sample selection is summarised in .

Data extracted and analysis

Although many authors in the sample used the concepts ‘sex’ and ‘gender’ as interchangeable synonyms and without defining them when describing inclusion, exclusion, or effects of being men or women, we used the combined term sex/gender in our data extraction templates. Authors generally documented body mass index (BMI) only in studies of diseases where weight was an important factor in a biological sense. However, as BMI is also strongly related to and entangled with the level of education, family economy, and other aspects of SES, we included it as a social factor when extracting data. We noted inclusion/exclusion criteria for each social category (sex/gender, race, SES, social connectedness, health behaviours, education, BMI). After identifying that sex/gender was the most commonly recorded of these social categories, we focused further analyses on how sex/gender was or was not addressed in research design, analysis, and interpretation. To do this, we re-read and re-extracted the following data from all papers: inclusion/exclusion criteria, whether the study topic was sex-specific, number and proportion of women and men in the study, and how sex/gender was addressed and reported in results and discussion. A narrative summary of methodological strengths and shortcomings overall was also documented for each study.

Results

The 57 trials reviewed are summarised in , (Citation20–Citation76). In total, six papers reported on sex-specific conditions (Citation36, Citation47) (Citation48, Citation58) (Citation68, Citation74). identifies social characteristics documented across the reviewed papers. Most frequently recorded was sex/gender (52/57, 91%), followed by race or ethnicity (30/57, 53%), or some aspect of SES (9/57, 16%). Although BMI, a possible proxy for SES, was sometimes recorded its use was solely as a physical indicator of risk. Social connectedness and past or present adversity, both known determinants of health, were not documented in the reviewed trials. Thirty-five studies (61%) had age-related exclusions, few of which were necessary given the condition being assessed. One trial excluded women without explanation. In this study of diabetes, subjects recruited through primary care practices were all men (Citation39). Conversely, in what was designed as a sex-specific study of the impact of peer support for mothers on maternal and child morbidity and mortality in Malawi, researchers allowed men to participate in women's support groups (Citation47). Pregnant women, or those who might become pregnant, were excluded in 13 of the 54 studies (24%) of either women alone or both men and women.

Table 1 Summary of reviewed RCTS

Table 2 Inclusion/exclusion of individual characteristics in reviewed RCTS (N=57)

documents whether and how sex/gender was addressed in the studies reviewed. We considered papers where women and men were included in proportions ranging from 40 to 60% as having equal representation. Of the 51 non-sex-specific trials, 20 (39%) enrolled women and men in roughly equal proportions, 22 (43%) included more than 60% men, in 5 (10%) more than 60% of participants were women, and sex/gender proportions were not documented in three studies conducted among adults and two among children. Not noted in is that the majority of papers in the sample used the concepts ‘sex’ and ‘gender’ as undefined synonyms when describing inclusions, exclusions, results, and in discussions.

Table 3 Addressing sex/gender in reviewed RCTS (N=57)

Explicit and implicit methodological aberrations were not uncommon (see ) particularly with respect to selection of participants. In five papers, for example, there were unclear reasons for exclusions or high numbers of unexplained dropouts among those already enrolled (Citation24, Citation30) (Citation44, Citation52) (Citation55). In a different study, 371 (~25%) of those randomised to the treatment group yet none in the control group were unavailable to consent and were therefore excluded (Citation53). In another study almost 80% of recruits were removed (Citation44). We noted that arbitrary and ill-defined options to exclude participants at intake or after were more common in trials with some or all funding from industry (90%) (Citation24, Citation30) (Citation39, Citation52–Citation55, Citation60) (Citation73) than solely from public sources (Citation44). For five of the eight trials that were not blinded, there was no reason related to the intervention itself that would preclude this standard methodology (Citation48, Citation53) (Citation56, Citation59) (Citation75).

Next we examined whether and how sex/gender differences were analysed and included in results. Of the 49 of 51 studies on non-sex-specific conditions that included both women and men, only 10 (20%) used these categories to differentiate findings either via disaggregating data (n=8) (Citation20, Citation34) (Citation63, Citation67) (Citation69–Citation72) and/or by examining interactions between sex/gender and other variables of interest (n=3) (Citation26, Citation63) (Citation70).

Aspects of sex/gender that were described in outcomes were sometimes discussed (Citation20, Citation51) (Citation57, Citation63) (Citation67, Citation71). Also, in one of the six studies of sex-specific conditions there was discussion of whether gender aspects like social roles, opportunities, constraints, and expectations inherent in being a woman might interact with findings (Citation48). Conversely, identified differences between women and men were, on occasion, not reported in results but alluded to in subsequent discussions (Citation48, Citation60) or in appendices (Citation54). Overall, the interactions between sex/gender and other social determinants of health (e.g. SES, education, race) that would enrich understanding were neither included nor discussed as missing explanatory indicators, possible sources of error, or as predictors of the outcome.

Discussion

In this systematic sampling review of recent RCTs, we have assessed whether social traits exemplified by sex/gender were included in or potentially biased findings. Studies continue to show that women are underrepresented in enrolment (Citation77, Citation78) in National Institutes of Health (NIH) funded clinical research despite funding guidelines (Citation79–Citation81) in research on specific diseases (Citation82–Citation84), in analyses (Citation85), and when mortality is an endpoint (Citation86). Our question went beyond inclusion of women to examine whether and how the impact of diversity in baseline social characteristics within study arms was addressed. We selected sex/gender for in-depth examination recognising that inclusion is a prerequisite for but does not alone address the social character of being men and women. It is because dissimilar characteristics of subgroups such as men and women can and do modify outcomes and should be addressed that major public funders are more and more insistent on inclusion (Citation10, Citation19) (Citation87). The European Commission website on Research & Innovations includes a Gendered Innovations section to support researchers by presenting examples of how to analyse sex and gender aspects in parallel (Citation88). Such resources reaffirm that inclusion alone does not identify impact. Evidence of the differential effect of sex/gender on, for example, cardiovascular disease diagnosis, treatment offered, and prognosis (Citation19, Citation89), or on pharmaco-dynamics in general is robust enough to recommend inclusion of sufficient numbers of participants to enable subgroup analyses for women and men (Citation13).

Our focus was whether and how sex/gender was addressed in clinical trials rather than whether this social characteristic modifies outcomes for specific interventions or diseases. Whether social circumstances are acknowledged as integral to outcomes and elevated to the level of variables for analysis rather than controlled into oblivion is a matter of methodology across RCTs regardless of their specific topic. We therefore did not limit the sample to studies of particular systems and included all RCTs published in the journals and time frame selected. This yielded a mix of individual and cluster randomised trials; public and private funders; and pharmaceutical, technologic, and educational interventions. To the best of our knowledge, no study prior to ours has systematically assessed sex/gender in formulation of the research question, design, analysis, and interpretation in randomly selected studies from high impact medical journals. The composite picture arising is one of loss of information at each step in the path from design, through recruitment, data analysis and interpretation, a loss that can embed error in evidence.

Research question and design

In general, men and women were included, although over-representation, usually of men relative to women, limited external validity for many of the trials reviewed. The preponderance of men in several studies of diseases with no male prevalence, studies that claimed random recruitment of participants, raises questions about interference in the selection process (Citation54, Citation73) as did subjective and undefined exclusions (Citation24, Citation30) (Citation39, Citation44) (Citation52–Citation55, Citation60) (Citation72, Citation73). In one study, the removal of almost 80% of recruits can only be assumed to introduce selection bias (Citation44). As mentioned earlier, arbitrary and ill-defined options to exclude participants at intake or during the study were more common in trials with some or all funding from industry (90%) (Citation24, Citation30) (Citation39, Citation52–Citation55, Citation60) (Citation73) than solely from public sources (Citation44). A European study of interventions to decrease cardiovascular mortality among diabetics did not mention why all participants were men. Being a woman was not among exclusion criteria, recruitment occurred in general practices where women are well represented, neither the interventions the disease studied nor the outcome were specific to men, and there was no indication in the title or abstract of the exclusion of women (Citation39). This was the sole study to demonstrate a total blindness to sex/gender that was criticised widely and became a reason for denial of public funding more than 20 years ago in the United States (Citation90). In contrast, a study of whether social networking can increase HIV testing among African- and Latino-Americans intentionally limited research on a non-sex-specific illness or intervention to men who have sex with men (Citation74). By being explicit about reasons for selecting an all-male population, the authors minimised bias in their research question. The study by Lewycka et al. (Citation47) on whether peer health education of women could increase breastfeeding rates and decrease morbidity or mortality in Malawi illustrates sex/gender bias via over-inclusion. Allowing men to attend peer groups for women in a setting where women generally lack autonomy created the potential for silencing or coercion of female by male participants. Put another way, having men participate in what should be a study of women's health education introduced potential bias arising from gender inequality. This was not considered in the paper.

Analysis and interpretation

Data related to sex/gender, although available, were often neither utilised nor discussed. Authors might argue that such data served as evidence that randomisation controlled the impact of baseline characteristics like sex/gender via equal distribution and that funding limitations precluded powering studies to examine different outcomes for women and men. However, one could suggest that such an argument is evidence of, and will perpetuate blindness to the impact of sex/gender on health outcomes. There were no examples of a priori consideration of sex/gender by randomisation within the groupings ‘men’ and ‘women’ rather than in the sample as a whole. In the 8 studies where results were disaggregated for men and women these findings were generally not discussed and none considered reasons for sex/gender differences (Citation20, Citation34) (Citation63, Citation67) (Citation69–Citation72). This silence, although methodologically appropriate (because subgroup analysis was not planned a priori) occurred in studies where enrolment was adequate to identify differences and so, a research opportunity was lost. Three examples illustrate this. A study of new drug regimens for rheumatoid arthritis found women's responses equalled those for men (Citation57). The authors noted that in prior research men had responded better than women to treatment, but made no comment about their novel findings and instead stated that there was no sex differential in response. In a study of interventions immediately following a STEMI (a kind of myocardial infarction) statistically significant differences in response by women and men were dismissed as a chance finding (Citation67). Finally, although the only predictor of prevalence of trachoma infection was the proportion of women in each randomised cluster studied (p=0.002), this was ignored while statistically insignificant variability across treatments (p>0.99) was summarised as possibly of importance (Citation38).

At times, authors’ statements did not match findings, putting a positive spin on interventions of no benefit or possible harm. New treatments that were no better than controls were termed ‘non-inferior’ (see comments in ). Although overstating benefit was most common in tests of new drugs, two publicly funded studies highlight how unshakeable beliefs shaped reporting (Citation47, Citation68). Both studies assumed that increasing breastfeeding rates would improve infant health in Africa. In each, the proportion of breastfed babies did increase; however, when there was no subsequent change in designated health outcomes authors hypothesised that there were likely other, non-measured advantages to breastfeeding. The evidence of no benefit from breastfeeding was, for whatever reasons, deemed unacceptable to report.

Social characteristics such as sex/gender are not always modifiers of the relationship between interventions and health outcomes. In treatment trials for endocarditis (Citation42) or pancreatic cancer (Citation69), sex/gender as a determinant or an effect modifier seemed unlikely. However, when sex/gender, race or SES matter will not be detected by randomising them into hiding. Without comment from authors it is impossible to determine what reasoning preceded limiting analyses to the group as a whole or if the impact of social circumstances was considered. Only by including subgroup analyses can researchers ascertain whether and when the measurement of social traits is relevant.

Limitations

Drawing general conclusions about research methodology from analyses of 57 studies must be done with caution. However, by randomly selecting among the 712 RCTs identified, the sample studied should be representative of all papers identified in the initial search. In addition, interim findings after analysing 28 of 57 papers did not change substantially when all reports were included, making it seem that we had identified a pattern and could generalise from it.

One might argue it is difficult to analyse research from the varying medical areas included in this review in the same way. However, the point here was not to evaluate the relevance or best way to analyse sex/gender in one and each disease or condition. Instead, we searched for patterns and an overview of whether researchers seem aware of, and addressed, the fact that the groups men and women are not identical but instead often differ with respect to important biological characteristics and social and environmental living conditions.

Conclusion

Few of the random samples of all RCTs published in five high-impact journals over 5 years assessed whether social circumstances altered outcomes. Fewer still attempted to interrogate findings with respect to sex/gender (or race or SES) and identify whether sex/gender acts as a modifier of the pathway from intervention to outcome. The theoretical robustness of the RCT is that it mimics animal experiments by controlling for, or randomly distributing and, therefore, removing unidentified and unmeasured human variability as sources of error. Baseline characteristics such as SES, race and sex/gender are, however, known determinants of health that can modify the relationship between exposures and outcomes of primary interest. Inherent in the methodology of clinical trials is the clean slate of equal background noise or impact of social characteristics like gender in all study arms but also the messiness of failing to hear the noise. It is only by listening by studying rather than randomising non-biological traits away, that research will identify whether and when social characteristics of participants affect outcomes.

Authors' contributions

Both authors designed the research and reviewed and analysed data. SPP carried out the literature search/data extraction and drafted the paper which was then reviewed and revised by KH.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study.

Acknowledgements

Both authors wish to thank the Umeå Centre for Gender Studies for supporting this research.

References

- Koskinen S, Martelin T. Why are socioeconomic mortality differences smaller among women than among men?. Soc Sci Med. 1994; 38: 1385–96. [PubMed Abstract].

- Krieger N, Smith GD. Bodies count and body counts: social epidemiology and embodying inequality. Epidemiol Rev. 2004; 26: 92–103. [PubMed Abstract].

- Phillips SP. Measuring the health effects of gender. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008; 62: 368–71. [PubMed Abstract].

- Connell RW. Gender. 2002; Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Ridgeway CL, Correll SJ. Unpacking the gender system: a theoretical perspective on gender beliefs and social relations. Gen Soc. 2004; 18: 510–31.

- Thorslund M, Wastesson JW, Agahi N, Lagergren M, Parker MG. The rise and fall of women's advantage: a comparison of national trends in life expectancy at 65 years. Eur J Ageing. 2013; 10: 271–7. [PubMed Abstract] [PubMed CentralFull Text].

- Courtenay WH. Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men's well-being: a theory of gender and health. Soc Sci Med. 2000; 50: 1385–401. [PubMed Abstract].

- Seifarth JE, McGowan CL, Milne KJ. Sex and life expectancy. Gend Med. 2012; 9: 390–401. [PubMed Abstract].

- Lorber J, Moore LJ. Gender and the social construction of illness. 2002; New York: AltaMira Press.

- Kaufman JS, MacLehose RF. Which of these is not like the others?. Cancer. 2013; 119: 4216–22. [PubMed Abstract] [PubMed CentralFull Text].

- Maas AHEM, van der Schouw YT, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Swahn E, Appelman YE, Pasterkamp G, etal. Red alert for women's heart: the urgent need for more research and knowledge on cardiovascular disease in women. Proceedings of the Workshop held in Brussels on Gender Differences in Cardiovascular disease, 29 September 2010. Eur Heart J. 2011; 32: 1362–8. [PubMed Abstract].

- Arnetz L, Ekberg NR, Alvarsson M. Sex differences in type 2 diabetes: focus on disease course and outcomes. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2014; 16: 409–20.

- Regitz-Zagrosek V. Sex and gender differences in pharmacology. 2012; Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- Nyberg F, Osika I, Evengård B. “The Laundry Bag Project” – unequal distribution of dermatological healthcare resources for male and female psoriatic patients in Sweden. Int J Dermatol. 2008; 47: 144–9. [PubMed Abstract].

- Hamberg K. Gender bias in medicine. Women's Health. 2008; 4: 237–43. [PubMed Abstract].

- Borkhoff CM, Hawker GA, Kreder HJ, Glazier RH, Mahomed NN, Wright JG. The effect of patients’ sex on physicians’ recommendations for total knee arthroplasty. CMAJ. 2008; 178: 681–7. [PubMed Abstract] [PubMed CentralFull Text].

- Kreatsoulas C, Anand S. Considering race/ethnicity and socio-economic status in randomized controlled trials. A commentary on Frampton et al.'s systematic review generalizing findings and tackling health disparities in asthma research. Soc Sci Med. 2009; 69: 1155–6. [PubMed Abstract].

- Phillips SP, Hamberg K. Women's relative immunity to the socio-economic health gradient: artifact or real?. Glob Health Action. 2015; 8 27259, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/gha.v8.27259.

- Swahn E. Stable or not, woman or man: is there a difference?. Eur Heart J. 2012; 33: 2769–70. [PubMed Abstract].

- Aberle DR, DeMello S, Berg CD, Black WC, Brewer B, Church TR, etal. Results of the two incidence screenings in the National Lung Screening Trial. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369: 920–31. [PubMed Abstract] [PubMed CentralFull Text].

- Anderson DR, Dunbar MJ, Bohm ER, Belzile E, Kahn SR, Zukor D, etal. Aspirin versus low-molecular-weight heparin for extended venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after total hip arthroplasty: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2013; 158: 800–6. [PubMed Abstract].

- Boyd MA, Kumarasamy N, Moore CL, Nwizu C, Losso MH, Mohapi L, etal. Ritonavir-boosted lopinavir plus nucleoside or nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors versus ritonavir-boosted lopinavir plus raltegravir for treatment of HIV-1 infection in adults with virological failure of a standard first-line ART regimen (SECOND-LINE): a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority study. Lancet. 2013; 381: 2091–9. [PubMed Abstract].

- Burmester GR, Blanco R, Charles-Schoeman C, Wollenhaupt J, Zerbini C, Benda B, etal. Tofacitinib (CP-690,550) in combination with methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors: a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013; 381: 451–60. [PubMed Abstract].

- Byrd JC, Furman RR, Coutre SE, Flinn IW, Burger JA, Blum KA, etal. Targeting BTK with ibrutinib in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369: 32–42. [PubMed Abstract] [PubMed CentralFull Text].

- Chakravarthy U, Harding SP, Rogers CA, Downes SM, Lotery AJ, Culliford LA, etal. Alternative treatments to inhibit VEGF in age-related choroidal neovascularisation: 2-year findings of the IVAN randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013; 382: 1258–67. [PubMed Abstract].

- Cooper CJ, Murphy TP, Cutlip DE, Jamerson K, Henrich W, Reid DM, etal. Stenting and medical therapy for atherosclerotic renal-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2014; 370: 13–22. [PubMed Abstract] [PubMed CentralFull Text].

- Cotton MF, Violari A, Otwombe K, Panchia R, Dobbels E, Rabie H, etal. Early time-limited antiretroviral therapy versus deferred therapy in South African infants infected with HIV: results from the children with HIV early antiretroviral (CHER) randomised trial. Lancet. 2013; 382: 1555–63. [PubMed Abstract] [PubMed CentralFull Text].

- Dennis M, Sandercock P, Reid J, Graham C, Forbes J, Murray G. Effectiveness of intermittent pneumatic compression in reduction of risk of deep vein thrombosis in patients who have had a stroke (CLOTS 3): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013; 382: 516–24. [PubMed Abstract].

- Devanand DP, Mintzer J, Schultz SK, Andrews HF, Sultzer DL, de la Pena D, etal. Relapse risk after discontinuation of risperidone in Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2012; 367: 1497–507. [PubMed Abstract] [PubMed CentralFull Text].

- Doody RS, Raman R, Farlow M, Iwatsubo T, Vellas B, Joffe S, etal. A phase 3 trial of semagacestat for treatment of Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369: 341–50. [PubMed Abstract].

- Dooley MA, Jayne D, Ginzler EM, Isenberg D, Olsen NJ, Wofsy D, etal. Mycophenolate versus azathioprine as maintenance therapy for lupus nephritis. N Engl J Med. 2011; 365: 1886–95. [PubMed Abstract].

- Douillard JY, Oliner KS, Siena S, Tabernero J, Burkes R, Barugel M, etal. Panitumumab-FOLFOX4 treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369: 1023–34. [PubMed Abstract].

- Eikelboom JW, Connolly SJ, Brueckmann M, Granger CB, Kappetein AP, Mack MJ, etal. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with mechanical heart valves. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369: 1206–14. [PubMed Abstract].

- Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, Covas MI, Corella D, Arós F, etal. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. N Engl J Med. 2013; 368: 1279–90. [PubMed Abstract].

- Fayad ZA, Mani V, Woodward M, Kallend D, Abt M, Burgess T, etal. Safety and efficacy of dalcetrapib on atherosclerotic disease using novel non-invasive multimodality imaging (dal-PLAQUE): a randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2011; 378: 1547–59. [PubMed Abstract] [PubMed CentralFull Text].

- Fleshner NE, Lucia MS, Egerdie B, Aaron L, Eure G, Nandy I, etal. Dutasteride in localised prostate cancer management: the REDEEM randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2012; 379: 1103–11. [PubMed Abstract].

- Forster A, Dickerson J, Young J, Patel A, Kalra L, Nixon J, etal. A structured training programme for caregivers of inpatients after stroke (TRACS): a cluster randomised controlled trial and cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet. 2013; 382: 2069–76. [PubMed Abstract].

- Gebre T, Ayele B, Zerihun M, Genet A, Stoller NE, Zhou Z, etal. Comparison of annual versus twice-yearly mass azithromycin treatment for hyperendemic trachoma in Ethiopia: a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2012; 379: 143–51. [PubMed Abstract].

- Griffin SJ, Borch-Johnsen K, Davies MJ, Khunti K, Rutten GE, Sandbæk A, etal. Effect of early intensive multifactorial therapy on 5-year cardiovascular outcomes in individuals with type 2 diabetes detected by screening (ADDITION-Europe): a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2011; 378: 156–67. [PubMed Abstract] [PubMed CentralFull Text].

- Hoffmann U, Truong QA, Schoenfeld DA, Chou ET, Woodard PK, Nagurney JT, etal. Coronary CT angiography versus standard evaluation in acute chest pain. N Engl J Med. 2012; 367: 299–308. [PubMed Abstract] [PubMed CentralFull Text].

- Horton MR, Santopietro V, Mathew L, Horton KM, Polito AJ, Liu MC, etal. Thalidomide for the treatment of cough in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012; 157: 398–406. [PubMed Abstract].

- Kang DH, Kim YJ, Kim SH, Sun BJ, Kim DH, Yun SC, etal. Early surgery versus conventional treatment for infective endocarditis. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366: 2466–73. [PubMed Abstract].

- Karim SSA, Naidoo K, Grobler A, Padayatchi N, Baxter C, Gray AL, etal. Integration of antiretroviral therapy with tuberculosis treatment. N Engl J Med. 2011; 365: 1492–501.

- Katz JN, Brophy RH, Chaisson CE, de Chaves L, Cole BJ, Dahm DL, etal. Surgery versus physical therapy for a meniscal tear and osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2013; 368: 1675–84. [PubMed Abstract] [PubMed CentralFull Text].

- Kølle SF, Fischer-Nielsen A, Mathiasen AB, Elberg JJ, Oliveri RS, Glovinski PV, etal. Enrichment of autologous fat grafts with ex-vivo expanded adipose tissue-derived stem cells for graft survival: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2013; 382: 1113–20.

- Lebwohl M, Swanson N, Anderson LL, Melgaard A, Xu Z, Berman B. Ingenol mebutate gel for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366: 1010–19. [PubMed Abstract].

- Lewycka S, Mwansambo C, Rosato M, Kazembe P, Phiri T, Mganga A, etal. Effect of women's groups and volunteer peer counselling on rates of mortality, morbidity, and health behaviours in mothers and children in rural Malawi (MaiMwana): a factorial, cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013; 381: 1721–35. [PubMed Abstract] [PubMed CentralFull Text].

- Liem S, Schuit E, Hegeman M, Bais J, de Boer K, Bloemenkamp K, etal. Cervical pessaries for prevention of preterm birth in women with a multiple pregnancy (ProTWIN): a multicentre, open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013; 382: 1341–9. [PubMed Abstract].

- Lo-Coco F, Avvisati G, Vignetti M, Thiede C, Orlando SM, Iacobelli S, etal. Retinoic acid and arsenic trioxide for acute promyelocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369: 111–21. [PubMed Abstract].

- Mallick U, Harmer C, Yap B, Wadsley J, Clarke S, Moss L, etal. Ablation with low-dose radioiodine and thyrotropin alfa in thyroid cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366: 1674–85. [PubMed Abstract].

- Marchioli R, Finazzi G, Specchia G, Cacciola R, Cavazzina R, Cilloni D, etal. Cardiovascular events and intensity of treatment in polycythemia vera. N Engl J Med. 2013; 368: 22–33. [PubMed Abstract].

- Mateos MV, Hernández MT, Giraldo P, de la Rubia J, de Arriba F, López Corral L, etal. Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for high-risk smoldering multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369: 438–47. [PubMed Abstract].

- Milstone AM, Elward A, Song X, Zerr DM, Orscheln R, Speck K, etal. Daily chlorhexidine bathing to reduce bacteraemia in critically ill children: a multicentre, cluster-randomised, crossover trial. Lancet. 2013; 38: 1099–106.

- Montalescot G, Bolognese L, Dudek D, Goldstein P, Hamm C, Tanguay JF, etal. Pretreatment with prasugrel in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369: 999–1010. [PubMed Abstract].

- Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Cella D, Reeves J, Hawkins R, Guo J, etal. Pazopanib versus sunitinib in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369: 722–31. [PubMed Abstract].

- Nguyen-Khac E, Thevenot T, Piquet MA, Benferhat S, Goria O, Chatelain D, etal. Glucocorticoids plus N-acetylcysteine in severe alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2011; 365: 1781–9. [PubMed Abstract].

- O'Dell JR, Mikuls TR, Taylor TH, Ahluwalia V, Brophy M, Warren SR, etal. Therapies for active rheumatoid arthritis after methotrexate failure. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369: 307–18. [PubMed Abstract].

- Parker C, Nilsson S, Heinrich D, Helle SI, O'Sullivan JM, Fosså SD, etal. Alpha emitter radium-223 and survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369: 213–23. [PubMed Abstract].

- Pickard R, Lam T, MacLennan G, Starr K, Kilonzo M, McPherson G, etal. Antimicrobial catheters for reduction of symptomatic urinary tract infection in adults requiring short-term catheterisation in hospital: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012; 380: 1927–35. [PubMed Abstract].

- Pirmohamed M, Burnside G, Eriksson N, Jorgensen AL, Toh CH, Nicholson T, etal. A randomized trial of genotype-guided dosing of warfarin. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369: 2294–303. [PubMed Abstract].

- Roberts JD, Wells GA, Le May MR, Labinaz M, Glover C, Froeschl M, etal. Point-of-care genetic testing for personalisation of antiplatelet treatment (RAPID GENE): a prospective, randomised, proof-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2012; 379: 1705–11. [PubMed Abstract].

- Roe MT, Armstrong PW, Fox KA, White HD, Prabhakaran D, Goodman SG, etal. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel for acute coronary syndromes without revascularization. N Engl J Med. 2012; 367: 1297–309. [PubMed Abstract].

- Shaukat A, Mongin SJ, Geisser MS, Lederle FA, Bond JH, Mandel JS, etal. Long-term mortality after screening for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369: 1106–14. [PubMed Abstract].

- Sihvonen R, Paavola M, Malmivaara A, Itälä A, Joukainen A, Nurmi H, etal. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus sham surgery for a degenerative meniscal tear. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369: 2515–24. [PubMed Abstract].

- Silbergleit R, Durkalski V, Lowenstein D, Conwit R, Pancioli A, Palesch Y, etal. Intramuscular versus intravenous therapy for prehospital status epilepticus. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366: 591–600. [PubMed Abstract] [PubMed CentralFull Text].

- Soofi S, Cousens S, Iqbal SP, Akhund T, Khan J, Ahmed I, etal. Effect of provision of daily zinc and iron with several micronutrients on growth and morbidity among young children in Pakistan: a cluster-randomized trial. Lancet. 2013; 382: 29–40. [PubMed Abstract].

- Thiele H, Wöhrle J, Hambrecht R, Rittger H, Birkemeyer R, Lauer B, etal. Intracoronary versus intravenous bolus abciximab during primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2012; 379: 923–31. [PubMed Abstract].

- Tylleskär T, Jackson D, Meda N, Engebretsen IM, Chopra M, Diallo AH, etal. Exclusive breastfeeding promotion by peer counsellors in sub-Saharan Africa (PROMISE-EBF): a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2011; 378: 420–7.

- Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, Chiorean EG, Infante J, Moore M, etal. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369: 1691–703. [PubMed Abstract] [PubMed CentralFull Text].

- Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhao X, Liu L, Wang D, Wang C, etal. Clopidogrel with Aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369: 11–19. [PubMed Abstract].

- Walmsley SL, Antela A, Clumeck N, Duiculescu D, Eberhard A, Gutiérrez F, etal. Dolutegravir plus abacavir-lamivudine for the treatment of HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369: 1807–18. [PubMed Abstract].

- White WB, Cannon CP, Heller SR, Nissen SE, Bergenstal RM, Bakris GL, etal. Alogliptin after acute coronary syndrome in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369: 1327–35. [PubMed Abstract].

- Wiviott SD, White HD, Ohman EM, Fox KA, Armstrong PW, Prabhakaran D, etal. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel for patients with unstable angina or non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction with or without angiography: a secondary, prespecified analysis of the TRILOGY ACS trial. Lancet. 2013; 382: 605–13. [PubMed Abstract].

- Young SD, Cumberland WG, Lee SJ, Jaganath D, Szekeres G, Coates T. Social networking technologies as an emerging tool for HIV prevention: a cluster randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2013; 159: 318–24. [PubMed Abstract].

- Zeuzem S, Soriano V, Asselah T, Bronowicki JP, Lohse AW, Müllhaupt B, etal. Faldaprevir and deleobuvir for HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369: 630–9. [PubMed Abstract].

- Zhu FC, Meng FY, Li JX, Li XL, Mao QY, Tao H, etal. Efficacy, safety, and immunology of an inactivated alum-adjuvant enterovirus 71 vaccine in children in China: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013; 381: 2024–32. [PubMed Abstract].

- Hoel AW, Kayssi A, Brahmanandam S, Belkin M, Conte MS, Nguyen LL, etal. Under-representation of women and ethnic minorities in vascular surgery randomized controlled trials. J Vasc Surg. 2009; 50: 349–54. [PubMed Abstract] [PubMed CentralFull Text].

- Furler J, Magin P, Pirotta M, van Driel M. Participant demographics reported in “table 1” of randomized controlled trials: a case of “inverse evidence”?. Int J Equity Health. 2012; 11: 14. [PubMed Abstract] [PubMed CentralFull Text].

- Vidaver RM, Lafleur B, Tong C, Bradshaw R, Marts SA. Women subjects in NIH-funded clinical research literature: lack of progress in both representation and analysis by sex. J Women's Health Gend Based Med. 2000; 9: 495–504.

- Geller SE, Koch A, Pellettieri B, Carnes M. Inclusion, analysis, and reporting of sex and race/ethnicity in clinical trials: have we made progress?. J Women's Health. 2011; 20: 315–20.

- Geller SE, Adams MG, Carnes M. Adherence to federal guidelines for reporting of sex and race/ethnicity in clinical trials. J Women's Health. 2006; 15: 1123–31.

- Jagsi R, Motomura AR, Amamath S, Jankovic A, Sheets N, Ubel PA. Under-representation of women in high-impact published clinical research. Cancer. 2009; 115: 3293–301. [PubMed Abstract].

- Weinberger AH, McKee SA, Mazure CM. Inclusion of women and gender-specific analyses in randomized clinical trials of treatments for depression. J Women's Health. 2010; 19: 1727–32.

- Johnson SM, Karvonen CA, Phelps CL, Nader S, Sanborn BM. Assessment of analysis by gender in the Cochrane reviews as related to treatment of cardiovascular disease. J Women's Health. 2003; 12: 449–57.

- Yang Y, Carlin AS, Faustino PJ, Motta MI, Hamad ML, He R, etal. Participation of women in clinical trials for new drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2000–2002. J Women's Health. 2009; 18: 303–310.

- Ramasubbu K, Gurm H, Litaker D. Gender bias in clinical trials: do double standards still apply?. J Women's Health Gend Based Med. 2001; 8: 757–64.

- Epstein S. Inclusion. The politics of difference in medical research. 2007; Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

- European Commission. Research & Innovations, SWAFS. Gendered innovations. Sex and gender policies of major granting agencies. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/research/swafs/gendered-innovations/index_en.cfm?pg=home [cited 19 January 2016]..

- Johnston N, Bornefalk-Hermansson A, Schenck-Gustafsson K, Held C, Goodman SG, Yan AT, etal. Do clinical factors explain persistent sex disparities in the use of acute reperfusion therapy in STEMI in Sweden and Canada?. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2013; 2: 350–8. [PubMed Abstract] [PubMed CentralFull Text].

- National Institutes of Health. NIH guidelines on the inclusion of women and minorities as subjects in clinical research. Fed Regist. 1994; 59: 14508–13.