Abstract

Introduction

The danger surrounding methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) has been well known for decades. Although MRSA was initially only associated with hospitals, livestock-associated MRSA is being increasingly connected to the way food-supplying animals are treated. However, little is yet known about farmers’ risk awareness and their knowledge of MRSA. Hence, the goal of this study was to discover farmers’ perceptions of MRSA.

Materials and methods

Two successive studies were performed. Study I analysed the connection between the attitudes of cattle and pig farmers towards MRSA complications and characteristics such as age and vocational training. Study II dealt with the connection between contact frequency with livestock and the risk of MRSA colonisation.

Results

For Study I, 101 questionnaires were completed. Analysis showed that the participants’ education level (p=0.042, α=0.05) and the animal species kept on their farm (p=0.045, α=0.05) significantly influenced their perceptions. Screening results from 157 participants within Study II showed that contact frequency and the participants’ particular profession were significantly decisive for MRSA prevalence (contact frequency: p=0.000, professional branch: p=0.000, OR=11.966, α=0.05).

Discussion

The results show a high degree of risk consciousness and responsibility among farmers. However, it is assumed that most farmers who took part in the studies were interested parties. Thus, the study results are valid only for the chosen livestock holdings. Ultimately, educational work is still needed. Joint projects between economics and science offer a good platform to spark farmers’ interest in the MRSA problem, as well as to inform and enlighten them about dangers and connections. Interdisciplinary research will contribute to a better understanding of drug resistance and to reducing the long-term use of antibiotics.

Although originally associated only with medical institutions, the prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in other areas is continually rising. Over the last few years, the bacteria have been detected as livestock-associated MRSA (LA-MRSA) in pigs, cattle, and poultry, as well as in animal keepers and veterinarians, who are considered an exposure risk group (Citation1). The main focus is on ST398, a clonal complex that is mutually transferable between livestock and humans (Citation2). The potential risks of LA-MRSA have been discussed since its discovery. Against this background, pig-holding enterprises are the main focus of critical public reports, but the bacteria have been detected on dairy and cattle farms as well (Citation3).

Research into the risks for humans and animals has been conducted across different disciplines, including agriculture, veterinary medicine, and human medicine (Citation4). However, we have limited knowledge about animal owners’ risk perceptions surrounding LA-MRSA. This was the foundation for the two studies illustrated in the following discussion. The aim of this paper is to provide the following information about animal keepers’ opinions under very different initial conditions.

With the help of two sequentially performed studies, the following hypotheses are evaluated:

Farmers have a general risk perception and risk awareness about the resistance problem.

There are differences in risk perception and risk awareness about preventive measures between farmers, depending on education levels.

Positive results for MRSA screening among farmers are related to the frequency of animal contact.

The goal of both studies was to illuminate the unique dual role of farmers as an at-risk group due to their activity in animal stables and as decision makers for the responsible handling of antibiotics. The insights gained from these studies have led to concrete suggestions for how to raise risk awareness and a sense of responsibility regarding antibiotic resistance.

Materials and methods

For the two studies, two different questionnaires were compiled for an interdisciplinary team of agronomists, human medical physicians, veterinarians, epidemiologists, and microbiologists.

The survey for Study I was conducted in Germany in the summer of 2014. It consisted of 38 questions, with 36 closed questions and 2 open questions. The survey was entered into the Unipark software program to create an online survey. A pre-test was conducted with three experts to verify the conclusiveness of the questionnaire and the feasibility of the survey in terms of time spent and the evaluability of the results; final changes were then made. Finally, the questionnaire was opened to active participation and the link to the survey was sent via email to several farmers who had previously participated in other projects and to three specialist web portals of federations and publishing houses in the agrarian sector. Because of this process, it is unfortunately not possible to say exactly how many farmers saw the questionnaires, as we do not know the number of farmers who visited the websites with the survey link. All farmers with animal husbandry experience were permitted to participate in the survey; selection by animal species occurred later. All data collected were then analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics 23. Overall, after eliminating errors such as partially completed questionnaires, 101 out of 249 questionnaires were eligible for analysis.

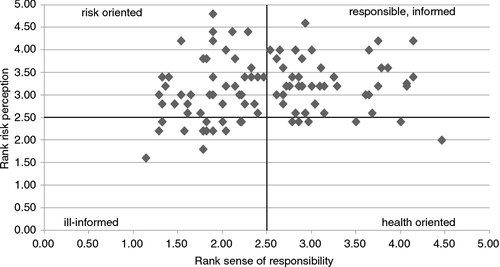

Dividing lines, coordinates, and four portfolio fields were subsequently defined to allocate the respondents to four categories based on risk perception and self-responsibility. The four categories were designated as follows:

Risk-oriented farmers

Health-oriented farmers

Responsible, informed farmers

ill-informed farmers

Every question from the questionnaire aimed at evaluating the participants’ risk perception and/or degree of self-responsibility was collated and analysed. The first group contained questions about risk perception concerning livestock and consumers, risk estimation of contamination, opinions about personal risk of colonisation, behaviour in hospitals, and opinions on handling antibiograms. The second group covered questions about the necessity of antibiograms, comparison of participants’ antibiotic consumption to that of colleagues, changes in antibiotic consumption since 2006, estimation of participants’ MRSA knowledge, and the execution of different hygiene measures inside and outside the stables. Depending on their answers, each participant was assigned between 1 and 5 points per question, 1 point being ‘very low risk consciousness’ or ‘very low self-responsibility’ and 5 points being ‘very high risk consciousness’ or ‘very high self-responsibility’.

The individual scores were used to determine values for the degree of risk consciousness and self-responsibility for each participant.

Each pair of values corresponds to a single position in the portfolio. Bar charts were chosen as a secondary form of visualisation. The inquiry in the second study took place during a producer community's general assembly in Germany in the summer of 2013 with 157 participants. In addition to the data gathered via questionnaire, nose swabs were taken from volunteers. All participants later received their respective test results. The swabs were tested for MRSA by culturing with selective agars. All nasal swabs were streaked on selective agar plates (CHROMagar MRSA, MAST Diagnostica GmbH, Reinfeld, Germany). Plates were incubated at 37±1°C for 24 h. The software package IBM SPSS Statistics 23 was used to statistically evaluate the survey and measurement data. Overall, 157 samples were analysed. The results were visualised using bar charts.

In order to determine the informative value of the individual cross tables, significance tests were conducted in parallel. To measure the results shown in and , and 5, the chi-square test was used. This test determines the probability that the population exhibits a relationship between the studied attributes. It is common to consider a p-value of less than 0.05 as significant. In this case, one would have to assume that there is a significant correlation between the frequency of A and B. To measure the results in , it was necessary to use Fisher's exact test as the requirements for the chi-square test were not met. As part of this evaluation, there was no 2×2 square table available. However, the interpretation of this test is similar to the chi-square test. Also for this test, a value below 0.05 constitutes a significant correlation. For the second study, the odds ratio was determined in addition to significance values.

Results

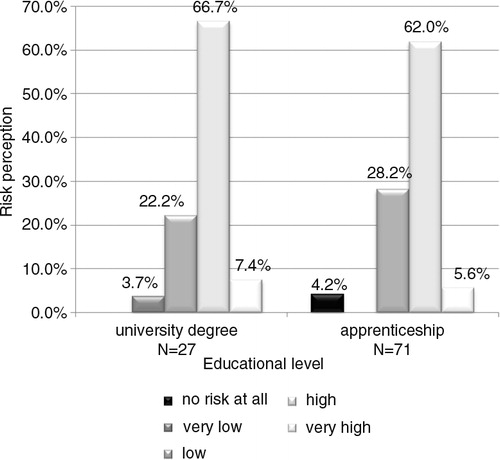

Two groups were formed based on participants’ education levels: one group of participants with university degrees and another group of participants with apprenticeships. shows that the perception of MRSA risk differed depending on the participant's education level. The participants’ degree of education is represented on the x-axis, while the y-axis represents the proportional distribution of the selected answers.

illustrates that people with a high level of education were inclined to perceive the risk as higher. Only 62.0% of the farmers with an apprenticeship considered the risk high, compared with 66.7% of participants with a university degree. Only 5.6% of participants with an apprenticeship considered the risk very high, whereas 7.4% of farmers with a university degree selected the same answer.

Low MRSA risk perception was observed in over one-quarter (28.2%) of animal owners with an apprenticeship. This value was slightly smaller (22.2%) for farmers with university degrees. None of these participants selected ‘no risk’. Thus a participant's education level (p=0.042, α=0.05) had a significant influence on his/her perception.

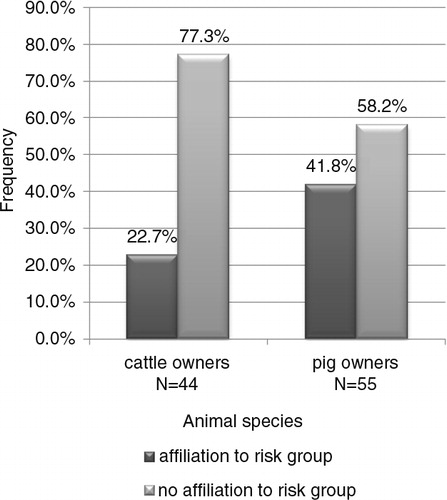

clarifies the participants’ opinions about being members of an at-risk group. These opinions are shown divided by animal species. Whereas only 22.7% of cattle owners saw themselves as members of an at-risk group, this opinion was held by 41.8% of pig owners. The majority of cattle owners (77.3%) and a smaller majority of pig owners (58.2%) had a different opinion. This connection is significant. Thus the animal species held on a farm (p=0.045, α=0.05) had a significant influence on the farmers’ perceptions.

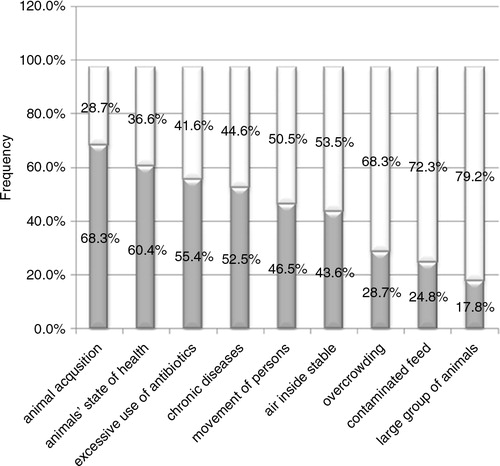

represents the farmers’ estimates about potential risk areas in their stables. The highest perceived risk was in the area of animal purchase, with 68.8% of farmers thinking that animal purchase increased MRSA risk. This was followed by the animal's health status (60.4%). Excessive use of antibiotics (55.4%) and the presence of chronic illnesses within the herd (52.5%) were also viewed as potential MRSA risk areas by the majority of participants. However, factors such as herd size (17.8%), overcrowding (28.7%), and contaminated feed (24.8%) were mostly not considered MRSA risk areas.

classifies participants depending on their respective degrees of risk perception and sense of responsibility. Using the responses of 101 test subjects, an estimate was made concerning the risk ascribed to various question answers and the participants were assigned to predetermined categories in the contingency table. Only 15 participants were allocated to the quadrant in the bottom left-hand corner, labelled ‘ill-informed’. The participants assigned to this field are characterised by a low degree of self-responsibility and risk perception, whereas the group assigned to the quadrant in the upper right-hand corner are both health- and risk-oriented. The participants in the other two categories tend to lean either towards a high level of self-responsibility – and are therefore classified as health-oriented – or towards a high level of risk perception – classified as risk-oriented.

As can be seen in the four-field matrix, the largest numbers of participants are located in the group of ‘risk-oriented’ farmers or the group of ‘responsible and informed’ farmers. As well as the answers to the specific questions, the survey provides further insights. Many farmers felt that they had been wrongfully portrayed by negative media. A number of participants used the opportunity for free expression at the end of the questionnaire, and all of them eventually brought up the issues of poor media representation of farmers. Many animal owners felt wrongfully accused of being mainly responsible for the complex MRSA problems in the healthcare sector. They asked for more differentiated media clarification to the public.

Among the participants in the second study who took part in both the survey and the screening for colonisation risk, 87.5% without direct animal contact tested negative for MRSA. Half of the participants with animal contact displayed MRSA colonisation.

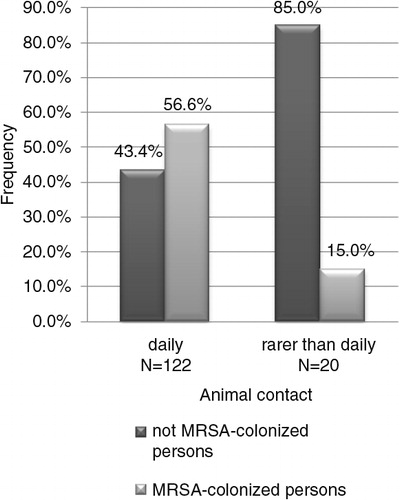

The risk of colonisation seems to depend on how regularly contact is made with animals and stable air. Comparing the two groups – those with daily contact and those with less-than-daily animal contact – showed that 56.6% of participants with daily contact were colonised with MRSA, whereas this value was only 15.0% for participants claiming less frequent animal contact (). The difference in relation to the proportions of colonised and non-colonised participants with daily and irregular animal contact is statistically significant (p=0.001, α=0.05).

Fig. 5 Percentage frequency of colonised and non-colonised participants with daily and irregular animal contact (p=0.001, α=0.05).

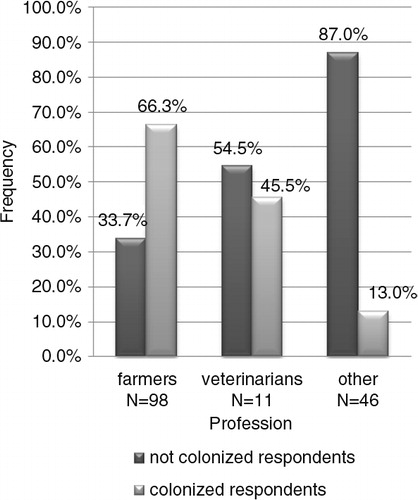

Several occupational groups participated in the study's screening examinations: farmers, veterinarians, and people with professions without intended animal contact. compares the three groups in terms of risk of MRSA colonisation.

As expected, farmers were more frequently colonised than veterinarians or other occupational groups; 66.3% of farmers who took part in the screening showed a positive MRSA result. Half of the tested veterinarians were colonised, whereas only 13.0% of people in other occupational groups tested positive. Thus the connection between occupational group and MRSA colonisation is statistically significant (p=0.000, α=0.05).

Calculating the odds ratio, the risk of animal owners and veterinarians becoming colonised through their daily work in the stable is 11.966. Despite the small number of people who did not have daily animal contact, the identified differences are statistically significant.

Discussion

For the first time, 258 persons – who actively wanted to partake in scientific studies to estimate MRSA risks – were available for empirical studies and screening examinations. These participants were people active in agricultural animal-holding enterprises, veterinarians, agricultural advisors, and animal owners and their respective families. Clear and partly statistically significant differences in risk estimation and the animal owners’ behaviour concerning antibiotics were clearly recognisable among the participants in the two studies.

Education level had a clear influence on risk perception. Farmers with a university degree evaluated some risks differently than farmers with an apprenticeship. In the context of a university education, man–animal–environment interactions are often put into a superordinate context and impulses for self-reliant action arise. Nationwide, 19.5% of farmers in Germany have a university degree, whereas the remaining 80.5% had completed an apprenticeship (Citation5).

More than a quarter of study participants were university graduates (26.7%); 70.3% were farmers who had completed an apprenticeship. Only a few participants indicated they had not been through an apprenticeship. The data published by BUND in Fleischatlas 2013 show no obvious decrease in the quantity of antibiotics used in veterinary medicine in Germany since 2006 (Citation6). The data from the GERMAP reports from the German Federal Office of Consumer Protection and Food Safety even show a rise in antibiotic consumption from 784.4 t in 2005 to 1619.0 t in 2012 (Citation7, Citation8). These data show that animal owners in general are not sufficiently aware of the connection between high antibiotic use and its consequences. In contrast, the participants in the current study seem particularly receptive to the topic and interested in different opinions. We must begin to encourage farmers to better understand the context and associated risks between the use of antibiotics and resistance emergence, to ensure that future antibiotics are used more effectively. The occurrence of MRSA-positive results among participants or their close family did not seem to influence their answers to questions about measures to protect themselves from colonisation. It is already known from other studies that MRSA is prevalent in 86.0% of pig owners and 77.7% of cattle owners (Citation1, Citation3). Therefore, these occupational groups are seen as at-risk groups. However, less than a third of participants in the online survey (31.7%, Study I) reported that they or one of their family members had been infected by MRSA at least once.

The fact that 157 participants were happy to be tested – whether they were colonised with MRSA or not – shows their interest in actively participating in addressing these problems. However, they were also particularly interested in learning more about their vocational risk. It must of course be remembered that the 157 participants were all members of German producer communities and the sample thus did not meet the randomness criterion. Nevertheless, in the authors’ opinion the participants are a representative sample in terms of pig and cattle farmers.

Cuny et al. (Citation9) also performed screenings to determine whether direct animal contact leads to an increased MRSA rate. The risk of being colonised is around 138 times higher for those with vocational contact with MRSA-positive pigs than for non-exposed people. Wissmann et al. (Citation10) confirm that farmers and veterinarians are colonised with MRSA more frequently than other occupational groups. In a statement, the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (Citation11) recommended assigning people with frequent animal contact to an at-risk group. However, the current study demonstrates that it is not animal contact itself but the regularity of stable visits that is responsible for colonisation risk. The risk for people with daily animal contact is significantly higher than for people who are only irregularly active in stables. Farmers, therefore, are at particular risk of becoming MRSA carriers compared to advisers or relatives with other professions. The odds ratio of animal owners and veterinarians becoming colonised through their daily work inside stables compared to those who do not have daily animal contact is 11.97. Veterinarians, at least those within the participant sample, who are in stables just as frequently as farmers, seem to have avoided colonisation thanks to their consideration of special hygiene measures such as wearing gloves and respiratory masks.

To recapitulate the characterisation of this study's participants, clearly shows that most participants had good advance information and a strong sense of self-responsibility. Compound projects between animal owners, producer communities, and scientists have the benefit of encouraging willingness to reconsider long-standing habits of handling antibiotics through personal contact. An increasing number of such public relations projects must be conducted in this area, in order to bring this to the attention of the vast number of pet owners and veterinarians and to reduce the future use of antibiotics and the emergence of resistance.

Finally, understanding the implementation of MRSA and Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamasen (ESBL) monitoring in livestock is a subsequent reaction (Citation12). Thus personal risk, along with the transmission risk between humans and animals for MRSA, can be measured. Examples show that if farmers are completely aware of their own situation and understand the connections within the multiresistance dynamics, they are also willing to make changes (Citation12).

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study.

Acknowledgements

We thank all farmers, veterinarians, and other participants for participating in this study. We also thank the farmers’ association for their cooperation.

References

- Köck R, Mellmann A, Schaumburg F, Friedrich AW, Kipp F, Becker K. The epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in Germany. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011; 108: 761–70.

- Köck R, Ballhausen B, Bischoff M, Cuny C, Eckmanns T, Fetsch A, etal. The impact of zoonotic MRSA colonization and infection in Germany. MRSA als Erreger von Zoonosen in Deutschland. Berl Munch Tierarztl Wochenschr. 2014; 127: 384–98.

- Spohr M, Rau J, Friedrich AW, Klittich G, Fetsch A, Guerra B, etal. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in three dairy herds in southwest Germany. Zoonoses Public Health. 2011; 58: 252–61.

- Schmithausen R. Was können Landwirte gegen die Entstehung und Ausbreitung von Antibiotikaresistenzen und Keimen tun?. 2014. Ministerium für Klimaschutz, Umwelt, Landwirtschaft, Natur- und Verbraucherschutz des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen..

- Statistisches Bundesamt. Land- und Forstwirtschaft, Fischerei. Landwirtschaftliche Berufsbildung der Betriebsleiter/Geschäftsführer Landwirtschaftszählung. 2010; Agrarstrukturerhebung. Available from: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Publikationen/Thematisch/LandForstwirtschaft/Landwirtschaftzaehlung/Landwirtschaftliche_Berufsbildung2032801109004.pdf?__blob=publicationFile [cited 14 February 2014].

- Badenschier F, Bartz D, Benning R, Birkel K, Börnecke S, Chemnitz C, etal. Fleischatlas 2013. Daten und Fakten über Tiere als Nahrungsmittel. 2014; Berlin: Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung, Bund für Umwelt- und Naturschutz und Le Monde diplomatique. 52.

- Bundesamt für Verbraucherschutz und Lebensmittelsicherheit. GERMAP: Bericht über den Antibiotikaverbrauch und die Verbreitung von Antibiotikaresistenzen in der Human- und Veterinärmedizin in Deutschland. Available from: http://www.bvl.bund.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/08_PresseInfothek/Germap_2008.pdf?__blob=publicationFile [cited 20 December 2014].

- Bundesamt für Verbraucherschutz und Lebensmittelsicherheit. GERMAP: Bericht über den Antibiotikaverbrauch und die Verbreitung von Antibiotikaresistenzen in der Human- und Veterinärmedizin in Deutschland. Available from: http://www.bvl.bund.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/08_PresseInfothek/Germap_2012.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2 [cited 21 May 2015]..

- Cuny C, Nathaus R, Layer F, Strommenger B, Altmann D, Witte W. Nasal colonization of humans with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) CC398 with and without exposure to pigs. PLoS One. 2009; 4: e6800.

- Wissmann A, Popp W, Hilken G. Methicillin-resistente Staphylococcus aureus in der Veterinärmedizin und dessen Bedeutung im Gesundheitswesen. Krh Hyg Inf Verh. 2011; 33: 126–9.

- Bundesinstitut für Risikobewertung. Menschen können sich über den Kontakt mit Nutztieren mit Methicillin-resistenten Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infizieren: Stellungnahme Nr. 014/2009. Available from: http://www.bfr.bund.de/cm/343/menschen_koennen_sich_ueber_den_kontakt_mit_nutztieren_mit_mrsa_infizieren.pdf [cited 20 December 2014].

- Schmithausen RM. Transfer of multidrug-resistant pathogens between humans and animals. 2015; Universität Bonn, Bonn: Dissertation of agriculture, Dissertation. 178.