Abstract

Background

For decades, the rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), such as gonorrhoea, chlamydia and syphilis, have increased in Greenland, especially within the young age groups (15–29 years). From 2006 to 2013, the number of abortions has been consistent with approximately 800–900 abortions per year in Greenland, which is nearly as high as the total number of births during the same period. Previous studies in Greenland have reported that knowledge about sexual health is important, both as prevention and as facilitator to stop the increasing rates of STIs. A peer-to-peer education programme about sexual health requires adaption to cultural values and acceptance among the population and government in order to be sustainable.

Objective

Formative evaluation of a voluntary project (SexInuk), in relation to peer-to-peer education with focus on sexual health. Two workshops were conducted in Nuuk, Greenland, to recruit Greenlandic students.

Design

Qualitative design with focus group interviews (FGIs) to collect qualitative feedback on feasibility and implementation of the project. Supplemented with a brief questionnaire regarding personal information (gender, age, education) and questions about the educational elements in the SexInuk project. Eight Greenlandic students, who had completed one or two workshops, were enrolled.

Results

The FGIs showed an overall consensus regarding the need for improving sexual health education in Greenland. The participants requested more voluntary educators, to secure sustainability. The articulation of taboo topics in the Greenlandic society appeared very important. The participants suggested more awareness by promoting the project.

Conclusion

Cultural values and language directions were important elements in the FGIs. To our knowledge, voluntary work regarding peer-to-peer education and sexual health has not been structurally evaluated in Greenland before. To achieve sustainability, the project needs educators and financial support. Further research is needed to investigate how peer-to-peer education can improve sexual and reproductive health in Greenland.

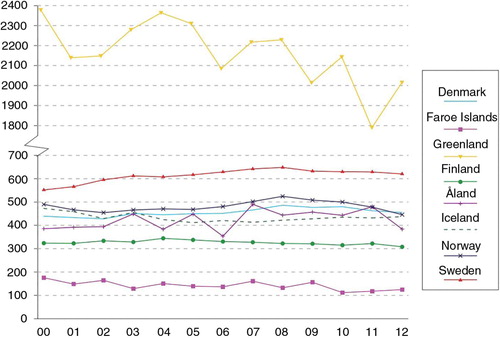

In recent decades, the rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), such as gonorrhoea and chlamydia, have been increasing in Greenland (Citation1, Citation2). In 2003–2006, the rates of both infections were reported high in Greenland compared to other Arctic countries, for example, Alaska (USA) and the Northern territories (Canada) (Citation3). The incidence of syphilis in Greenland has increased, from zero cases in 2010 to 85.3 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2014 (Citation4). The stated STIs are mainly affecting the young age groups (15–29 years) (Citation3, Citation4). From 2006 to 2013, the number of abortions has been consistent with approximately 800–900 abortions per year in Greenland, which is nearly as high as the total number of births during the same period (Citation5–Citation9). The women aged between 20 and 24 years accounted for the highest percent of abortions (Citation6, Citation8). The total abortion rate in Greenland differs markedly from other Nordic countries. In 2012, the total abortion rate in Greenland was 2,000 abortions per 1,000 women (aged 15–49 years). In comparison, the total abortion rate in other Nordic countries (Faroe Island, Norway, Denmark, etc.) was less than 700 abortions per 1,000 women (aged 15–49 years) in the same period, see (Citation10). To our knowledge, the exact number of unintended pregnancies in Greenland is not available in the literature or in statistical reports. In Greenland, it is solely up to the pregnant woman herself to decide whether an abortion is to be performed (Citation11). However, several cultural concerns may be considered: lack of consistent contraception use, short- and long-term consequences of abortion procedure, the husband's wish not to have a child, and a gap between what the women know about contraception and what the health communities believe they can teach them (Citation12, Citation13). In addition, Greenlandic families have a strong influence on whether or not a woman has an abortion (Citation14, Citation15). Regardless of the well-known problems concerning reproductive health in Greenland, the subject has not been prioritized in the Greenlandic Public Health Program (Inuuneritta II) 2013–2019 (Citation16).

Fig. 1. Total abortion rate per 1,000 women (aged 15–49 years) (y-axis) per year in 2000–2012 (x-axis). Calculated from the age-specific abortion rates for the selected Nordic countries. Reproduced with permission from NOMESCO (Citation10).

Expectedly, awareness of sexual and reproductive health among the youth in Greenland is an important factor to reduce the number of STIs and the abortion rates, respectively (Citation17). Yet, focusing only on providing factual information about sexual health may not be sufficient or effective in reducing negative sexual health outcomes (Citation18). Although sexual health education is mandatory in the public schools in Greenland as a part of the course “Personal Development” (Citation19), no studies show whether all pupils receive adequate and comprehensive sexual health education, with focus on anatomy, contraception, STIs as well as sensitive topics, such as love, sexuality, and relationships. In addition, families in Greenland will postpone or avoid talking about sexual health as it is considered awkward and difficult (Citation20). Still, direct communication regarding these topics can be effective in reducing STIs and promoting sexual health (Citation21). By implementing sexual health education, young people are ensured sufficient knowledge regarding sexual health, and, furthermore, it helps to fight taboos. Sexual health education in the public schools has existed for many years, but within a few years the teaching methods have developed drastically (Citation22, Citation23). Peer-to-peer education, for example, education performed by young people to young people, and a young-individual focused approach is a widespread practice to promote sexual health. Peer-to-peer education is a popular method among young people as it creates a fun and comfortable teaching atmosphere, which allows students to talk actively about sexual health (Citation24). Furthermore, peer-to-peer education introduces visual demonstrations, activity/behaviour games and icebreakers.

Peer-to-peer education regarding sexual health has, to our knowledge, only been tried once before in the town Aasiaat at the Greenlandic west coast. The project was named the Sex Pilots, but whether it was structurally evaluated or implemented in other Greenlandic towns is unknown. In order to create a basic platform for a sexual health educational programme for pupils in the Greenlandic public school system (7–10 grade), the project SexInuk was initiated. The aim was to establish a sustainable project targeted to recruit Greenlandic nursing and teaching students to draw focus to the sexual health issues. These students are relevant to address since they have a general interest in health and education. The method in the SexInuk project is based on peer-to-peer education and was conducted through workshops held by Danish medical students. The idea is to improve the sexual health among young age groups in Greenland by educating Greenlandic students, who then educate the pupils about STIs, anatomy, contraceptives etc. in the native language. Hence, the project is a peer-to-peer education programme. The project is to be implemented at the public schools in Nuuk, Greenland. Since the SexInuk project is voluntary, the commitment from the Greenlandic students is vital for the sustainability of the project in Greenland.

Thus, the objective was to conduct a formative evaluation of the SexInuk project in its pilot phase: primarily, to improve the project in relation to peer-to-peer education with focus on sexual health, and secondly, to adapt the project to cultural values in the future.

Methods and materials

The SexInuk project was established in 2012. The planning, fundraising and conduction of the workshops was carried out by Danish medical students with experience and knowledge about peer-to-peer education and voluntary work in Denmark. The Danish delegation was responsible for contact and arrangement of cooperative agreements with the Institute of Nursing Science and Health Research in Nuuk – Peqqissaanermik Ilinniarfik (PI), the Office of Health & Prevention in Greenland (Early Intervention in Greenland – PAARISA), the Department of Health & Infrastructure at the Greenlandic Home Rule Government and the Greenlandic School principal in Nuuk at Sermersooq municipality.

Workshops

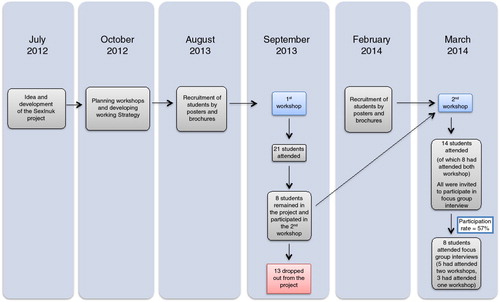

Two workshops were held at PI, in September 2013 and in March 2014, respectively. The purpose of the workshops was to recruit Greenlandic students to be volunteer peer educators. Prior to the workshops, information was distributed through posters and brochures. Participation of Greenlandic students in the workshops depended on interest in sexual health and awareness of the project via posters and brochures. At the first workshop, the target group was Greenlandic nursing students. Twenty-one Greenlandic students participated in the first workshop (20 nursing students from PI and 1 student from University of Greenland). In the second workshop, the recruitment of students was assigned to the nursing student's responsibility. The participants at the second workshop were primarily nursing students; however, teaching students from the Teacher Seminar in Nuuk and students from the University of Greenland also participated in the second workshop. Hence, the second workshop counted 14 Greenlandic students (8 nursing students, 4 teaching students and 2 students from University of Greenland). shows a timeline med flow diagram for inclusion of participants in workshops and focus group interviews (FGIs). Each of the two workshops lasted 3 days from approximately 1 to 5 pm. The workshops included (a) introduction to the SexInuk project and voluntary work, (b) presentation from a nurse employed at Queen Ingrid's Hospital (abortion in Greenland) and an employee from PAARISA (sexual health problematic in Greenland) and (c) implementation of sexual health education in public schools in Greenland. This way, the Greenlandic students could get an idea of how the main topics (anatomy, contraption and STIs) should be presented by visual demonstrations, and how activity/behaviour games and icebreakers were performed. Icebreakers are simple games or exercises used for introduction during the sexual health education and often have elements of direct learning. The educational methods used were based on a Danish model, recognized by the sexual health education programme in Denmark (Citation25).

Focus group interview

Study population

Fourteen students from the second workshop were invited to an FGI. The aim of the FGI was to conduct a formative evaluation of the SexInuk project, and to collect qualitative feedback on feasibility and implementation of the project. It was not possible to invite the participants from the first workshop, since some participants had dropped out from the project (13 participants), see . Eight female students from the second workshop were recruited to the FGIs, which was our final study population (participation rate 57%). Five of the students had completed both the first and second workshops. All participants had completed 1–9 grade in a Greenlandic public school. The eight students were distributed into two groups depending on which day the students could participate in the FGI, with four people in each of the two groups. The two interview groups are referred to as focus group 1 and focus group 2.

Environment

The setting for the FGI was comfortable and familiar, as the classroom used was the same as that used for the second workshop. Participants were instructed to turn off their cell phones, and a note was placed on the door to the room that stated: “Please: Do not disturb – interview in progress.”

Moderator and assistant moderator

Two Danish medical students conducted the FGIs. The language throughout the FGI was Danish, since all Greenlandic students spoke and understood Danish. Prior to the FGIs, the moderator explained the role of the moderator and the assistant moderator to the participants. The moderator was responsible for the FGI, while the assistant moderator was responsible for the technical equipment, seating arrangements and taking notes during the FGI. The notes included participants’ body language, distractions in the room, head nodding etc. The moderator used the following approach: welcome, ground rules, overview and topics, presentation of the participants, and then the first questions. To ensure compatibility, predetermined questions (presented in the Questionnaire section and the Result section; Table ) were applied at the FGIs. The purpose was to create a permissive and tolerable atmosphere among the participants in order to ensure a comfortable conversation. The guidelines for the FGI were followed by elementary instructions for designing and conducting FGIs (Citation26, Citation27).

Questionnaire

Prior to the FGI, the participants completed a 3-page questionnaire in Danish. It took 5–10 minutes for the participants to complete the questionnaire. The first page contained personal information about age, gender, educational level and participation in one or two workshops. At the second page, a few simple questions were asked, with the participant's subjective experience of greater knowledge regarding anatomy, STIs, contraception and activity/behaviour games or icebreakers, for example, “Did you experience greater knowledge about chlamydia after participating in the SexInuk workshops” (Yes/No/Unchanged/Do not know). Finally, the students had to describe their own experiences with sexual health education in the public school and give any additional comments to the project.

Data analysis

The Danish medical students, who conducted the workshops and the FGIs, were responsible for the data analysis. The questionnaire data were analyzed using Excel (Microsoft Office, software edition 2011), due to simple questions and few participants. The FGIs were audio-recorded. Subsequently, the FGI was systematically transcribed using Word (Microsoft Office, software edition 2011) and iTunes (Apple Music, software edition 11.1.5 OS X). Afterwards, the transcripts were read and crosschecked. The transcripts were analyzed by the predetermined questions. The Danish medical students discussed the overall answers. No verbal disagreements occurred among the participants during the FGIs, which allowed the individual answers to be merged. Subsequently, the answers in the two focus groups were compared to find diversities and similar answers. During this procedure, the transcripts were reviewed again.

Ethics

The Ethics Committee for medical research in Greenland approved the SexInuk project. Informed consent was signed before enrollment in the FGI. All participants were informed about the purpose of the FGI and accepted participation.

Results

The demographics of the participants are shown in Table . The participants in focus group 2 appeared older than the participants in focus group 1. The majority of participants were nursing students (5 out of 8). The four participants in focus group 1 had participated in two workshops, and furthermore, they all had experience with peer-to-peer education in the public school in Greenland, since they had been teaching about sexual health to Greenlandic pupils, which was only the case for one participant in focus group 2.

Table I. Demographics of participants in focus groups 1 and 2 (N=8)

The brief questionnaire (Table ) regarded the participants’ subjective experiences of greater knowledge regarding certain main topics, for example, anatomy, contraception and STIs, after participation in the workshops. The results show that 7 out of 8 participants stated to have the subjective experience of greater knowledge about STIs. More than half of the participants stated to have the subjective experience of greater knowledge concerning male anatomy and contraceptives. Few of the participants were familiar with activity/behaviour games and icebreakers prior to the workshop. Most of the participants (5 out of 8) had received some kind of sexual health education in public school. However, from their subjective point of view the quality and quantity of the sexual education in the public schools differed considerably.

Table II. Questionnaire analysis for participants in focus group interviews (N=8)

A comparison of the two FGIs is provided in Table along with the predetermined questions. The answers are merged by the participant's individual answers.

Table III. Comparison of answers from the focus groups 1 and 2 by merging of individual answers

The two groups agreed that a good sexual educator was a person with knowledge about sexual health and comprehensive understanding of cultural values. Focus group 1 reported from their subjective point of view that sexual health education was non-existing in some public schools. There was great consensus between the two groups regarding thoughts about benefits of the workshops, primarily that behavioural changes are needed in order to improve the sexual health in Greenland. There was a remarkable difference concerning the questions of what methods were useful and what methods were not worthwhile during the workshops. Both focus groups stated that the educational methods were good, and that the participants could use the knowledge from the workshops privately and professionally. The FGIs revealed an overall understanding within the cultural values of sexual health issues and taboo topics in the Greenlandic society. Both groups reflected on the future of the project and gave relevant advice concerning sustainability. According to the Greenlandic students to ensure sustainability, there is a need for more voluntary peer educators and further publicity (posters, TV commercials, etc.) to create more awareness about the project. Also, the participants in FGI 1 discussed the importance of governmental support and the lack of political concern regarding sexual and reproductive health. Furthermore, there was general agreement concerning the need for improving sexual health education in public schools, and overall need for greater knowledge about sexual health in the Greenlandic community.

One of the most encouraging citations during the FGI concerned the youth's future in Greenland:

… where we (peer educators) give them (the Greenlandic youth) a match, so they can light their own candle. We will not light the candle for them, but they can decide to light the candle themselves. Thus, they make their own choice ….

Discussion

The current study assesses a formative evaluation of the feasibility and implementation regarding a voluntary peer-to-peer education programme about sexual health in Greenland. Sexual and reproductive health in Greenland is an important topic. We believe that the use of peer-to-peer education is a valuable tool when it comes to educating young people about sexual and reproductive health. The educational methods used in the SexInuk project are based on a Danish model (Citation25). However, because of the cultural differences between Greenland and Denmark, caution must be taken when applying the same methods. Thus, it is important to continuously evaluate the project to fit it into Greenlandic settings.

The Greenlandic students experienced a subjective greater knowledge during the workshops, especially about STIs and to some extent male anatomy and contraceptives. Furthermore, the Greenlandic students reported that knowledge about cultural values is important to be a good sexual educator and that taboo topics need to be articulated. The learning methods in the workshops were educational for the Greenlandic students. The participants’ answers provided an insight as to whether the programme is correctly constructed and whether or not it could be adapted to public schools. From our insights, an example of a culturally relevant sexual health education in public schools in Greenland could include the same elements as the Danish model with presentation of anatomy, STIs and contraception; supplemented with simple activity/behaviour games and icebreakers, which the Greenlandic students found educational and fun. Thus, these methods could easily be used in Greenlandic public schools. However, in our experience, it is necessary to respect cultural differences regarding the Greenlandic students’ need for personal space and timidity, but also that the Greenlandic students like to laugh and have fun.

We are now aware of the importance of cultural experiences and understanding when implementing peer-to-peer education in Greenland. The language barrier needs to be respected, as well as concerns regarding recruitment of future peer educators. By using a language that is considered too provocative, you risk, unintentionally, to exceed personal boundaries and create an uncomfortable atmosphere. Our overall recommendation is to organize the education programme to the student/pupil's educational level and to use a combination of formal and/or humourous terms, which can create a natural atmosphere. Thus, we have experienced that simple directions for language use are necessary.

In the last century, cultural values and beliefs about sexuality have changed considerably in Greenland. The small settlements were undisturbed communities with a liberal attitude. Sexuality and intercourse were informal and concerned reproduction, hereby survival of the community. In the recent decades, the Westernization in Greenland has resulted in a dilemma regarding the private love life versus the sexual liberation (Citation28, Citation29). These historical and cultural changes should be considered when teaching sexual health in Greenland. In the SexInuk project, the approach was humble and the Greenlandic students assessed the different activity/behaviour games and icebreakers in the workshops. This allowed us to adjust the project to present cultural values in Greenland.

The main limitations of this study are the recruitment of participants (selective and few) and the data analysis of the qualitative method, which gives certain selection bias and interpretation problems. All participants were women; a gender variation would have been ideal. However, this was not a possibility since only one participant in the second workshop was male. The participants were not asked about ethnicity. Yet, all participants had completed 1–9 grade in the Greenlandic public school, and only one participant had been born outside Greenland. The FGIs were conducted by moderators well known to the participants, because moderators were a part of the Danish delegation. This may have influenced the participants’ answers. Ideally, the moderators should have been unknown to the participants and speaking the native tongue in order to obtain an objective opinion. In addition, the brief questionnaire was vague regarding the simple questions about subjective experience of greater knowledge within anatomy, STIs and contraception. Also, the questionnaire had not been validated or piloted before use, and finally the participants were asked retrospectively. Hence, future work could include a questionnaire with a Likert scale, and a before-and-after evaluation to compare. Due to subjective expressions the qualitative design has its limitations. Some answers in the FGIs were not available, since the participants did not answer the given question, resulting in missing answers for unknown reasons. In addition, a key limitation is the data analysis, since the qualitative data should have been analyzed in a validated analysis programme like Atlas.ti or similar. The workshops were only conducted in Nuuk, which cannot be representative for Greenland as a whole.

We experienced several difficulties regarding the implementation of the project. Meetings and communication are challenged by the geographical distance and time difference between Denmark and Greenland. To achieve sustainability with this project, it is essential to have financial support in order to ensure a strong consistent programme. Sexual and reproductive health needs political awareness, and the participants also emphasized this. One of the main challenges was to maintain consistency from the peer educators. The voluntary involvement from the Greenlandic students decreased when the Danish delegation left Greenland. This low level of commitment can be due to several cofactors such as lack of interest, time management and little experience with voluntary work. Thus, because of lack of experience with volunteer work among the Greenlandic students, sustainability is challenging.

A Greenlandic study called Inuulluataarneq (Having the Good Life) implemented a sexual health behavioural intervention in two communities in Greenland (Citation17, Citation30) (Citation31). The overall purpose was to reduce STIs. The results reported that a key factor was parent/guardian communication regarding essential sexual health topics. In connection to these findings, our study emphasizes the importance of communication about sensitive sexual health topics in order to decrease taboos and thereby empowering young people to act responsibly regarding sexual health.

The Sex Pilots was a previous sexual programme in Greenland from the mid to late 1990s in the town Aasiaat. It was established by a Danish nurse, PAARISA and the local municipality (Citation32), and was an attempt from the Greenlandic government to provide peer-to-peer led sexual health education. However, to our knowledge the programme has not been structurally evaluated, thus we cannot compare our data concerning this pilot-phase implementation.

An ongoing project named FOXY (Fostering Open eXpression among Youth) (Citation33) has been a great success in the Northwestern Territories in Canada at Nunavut and Yukon. Briefly, the purpose is open dialogue with young women about sexual health, sexuality and relationships:

FOXY a participatory action research project, which means youth are involved with all aspects of the project, from its development to its implementation and the evaluation. The research component of FOXY involves looking at the effectiveness of FOXY for empowering and facilitating dialogue about sexual health issues. (Citation34)

There is a great similarity between the project purpose of FOXY and SexInuk. Still, the major difference is the effort needed by volunteers in SexInuk.

Improved and comprehensive sexual health education is recommended in other Arctic countries (Citation35), to facilitate a positive view on sexual health topics.

In summary, to our knowledge peer-to-peer education has not been structurally evaluated in Greenland before. It is important to emphasize the importance of sexual health education among the Greenlandic youth, in order to reduce the historical high rates of STIs as well as the number of abortions. Knowledge and communication are in our opinion important tools. Furthermore, major sexual health disparities are present, when comparing Greenland with other Nordic countries. This project has recognized that it is possible to raise awareness and to create a well-functioning team of peer educators by recruiting Greenlandic students, who can speak Greenlandic and have knowledge of Greenlandic cultural values. The educational methods used in the project appeared to create an atmosphere of trust and to break down barriers regarding taboo topics. To ensure the success of a sexual health education programme, sustainability, publicity, and general acknowledgement is needed. Thus, there is a need for continuous evaluation of the benefits and limitations of this method in the SexInuk project. Further research is needed to investigate how sexual peer-to-peer education can improve sexual and reproductive health in Greenland.

Authors’ contributions

A-SH and A-KSK drafted the first version of the manuscript. All authors participated in the acquisition of statistical data and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. The first two authors, A-SH and A-KSK, contributed equally to this work.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The SexInuk project has received financial support from the NAPA foundation, the Nuna foundation, the DGO foundation, BHJ foundation, Sorlak, Lionklubbernes Grønlandsfond, Erik Thunes Legat of 1954, Dansk Ungdoms Fællesråd (DUF) and International Medical Corporation Committee (IMCC). The authors have received no personal financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgements

We thank Birgit Hansen [project coordinator at the Office of Health & Prevention in Greenland (Early Intervention in Greenland – PAARISA)], Bodil Karlshøj, (project coordinator at Institute of Nursing Science and Health Research, Nuuk) and Suzanne Møller (head of department, at Institute of Nursing Science and Health Research, Nuuk) for helpful assistance. A special thanks to the volunteer Greenlandic students for participating in the SexInuk workshops and focus group interviews. A special appreciation to Jonatan Kjeldsen for his contribution, dedication and friendship.

References

- Statistics Greenland. Calculation of sexually transmitted infections in Greenland (2009–2014), by infection, age, town, year and gender. [cited 2015 Aug 20]. Available from: http://bank.stat.gl/pxweb/da/Greenland/Greenland__SU__SU01/SUXLSKS1.px?rxid=SUXLSKS120-08-2015.

- Statistics Greenland. Greenland in figures 2013. Table: reported infectious diseases (2004–2010). 2013; Nuuk, Greenland: National Board of Health and Statistics Greenland. 29.

- Gesink Law D, Rink E, Mulvad G, Koch A. Sexual health and sexually transmitted infections in the North American Arctic. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008; 14: 4–9.

- Albertsen N, Mulvad G, Pedersen ML. Incidence of syphilis in Greenland 2010–2014: the beginning of a new epidemic?. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2015; 74 28378, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v74.28378.

- Statistics Greenland. Greenland in figures 2013. Table: live births in Greenland (1973–2012). 2013; Nuuk, Greenland: National Board of Health and Statistics Greenland. 10.

- Statistics Greenland. Greenland in figures 2013. Table: legal abortions in Greenland (2006–2010). 2013; Nuuk, Greenland: National Board of Health and Statistics Greenland. 28.

- Statistics Greenland. Greenland in figures 2015. Table: live births in Greenland (1973–2014). 2015; Nuuk, Greenland: National Board of Health and Statistics Greenland. 10.

- Statistics Greenland. Greenland in figures 2015. Table: legal abortions in Greenland (2008–2013). 2015; National Board of Health and Statistics Greenland. 28. [cited 2015 Aug 20]. Available from: http://www.stat.gl/publ/da/GF/2015/pdf/GreenlandinFigures2015.pdf.

- Meldgaard S. Reducing unwanted pregnancies in Greenland. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2004; 63(Suppl 2) 267–9..

- NOMESCO. Health statistics for the Nordic countries 2014. 2014 [cited 2015 Aug 20]. p. 50. Available from: http://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:781991/FULLTEXT03.pdf.

- NOMESCO. Health statistics for the Nordic countries 2014. 2014 [cited 2015 Aug 20]. p. 42. Available from: http://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:781991/FULLTEXT03.pdf.

- Bielecki I-L. Reasons for repeat induced abortions among Greenlandic women (Abstract). 2005. [cited 2015 Aug 20]. Available from: http://mph.ku.dk/uddannelsen/master/afhandlinger/afhandlinger/154._Bielecki__Ingelise.pdf.

- Information about induced abortion. Danish Health portal, sundhed.dk [in Danish]. 2014 [cited 2015 Aug 11]. Available from: https://www.sundhed.dk/sundhedsfaglig/laegehaandbogen/gynaekologi/tilstande-og-sygdomme/abort/abort-provokeret/.

- Montgomery-Andersen R, Douglas V, Borup I. Literature review: the “logics” of birth settings in Arctic Greenland. Midwifery. 2013; 29(11): e79–88.

- Montgomery-Andersen R. Referral in pregnancy: a challenge for Greenlandic women. [Master of Public Health]. 2005; Göteborg, Sweden: Nordic School of Public Health. 7 p..

- Inuuneritta II (2013–2019): the Greenlandic Public Health Program. [in Danish]. 2013 [cited 2015 Aug 20]. Available from: http://peqqik.gl/Footerpages/Publikationer/Inuuneritta_2.aspx?sc_lang=da-DK.

- Rink E, Montgomery-Andersen R, Anastario M. The effectiveness of an education intervention to prevent chlamydia infection among Greenlandic youth. Int J STD AIDS. 2015; 26: 98–106.

- Canadian guidelines for sexual health education. 2008. [cited 2015 Aug 14]. Available from: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/cgshe-ldnemss/theory-eng.php.

- Sexual health education in Greenland. Teaching plans for the course “Personal Development” at the Greenlandic public schools. Inerisaavik (University of Greenland) [in Danish]. 2004 [cited 2015 Aug 20]. Available from: http://www.inerisaavik.gl/fileadmin/user_upload/Inerisaavik/Laereplaner_dk/Aeldste_dk/PU_aeldste_dk.pdf.

- Rink E, Montgomery-Andersen R, Tróndheim G, Gesink D, Lennert L, Kotalawala N. Kleist Pedersen B, Nielsen FAJ, Langård K, Pedersen K, Rygaard J. The role of personal responsibility, trust in relationships, and family communication in the prevention of sexually transmitted infections amoung Greenlandic youth: focus group results from Inuulluataarneq. Grønlandsk Kult og Samf 2010–12 (Greenland's cultural and social research 2010–12). 2012; Nuuk: Ilisimatusarfik. 198–208.

- Montgomery-Andersen R, Anastario M. “Today we are not good at talking about these things”: a mixed methods study of Inuit parent/guardian – youth sexual health communication in Greenland. Int J Indigen Health. 2014; 10: 83–98.

- Bjerregaard S, Jensen J, Fraenkel AS, Albeck G. Seksualundervisning – inspiration og metode (Sexual health education – inspiration and method). [in Danish]. 2009; Odense, Denmark: Center for Sex og Sundhed.

- Gundersen M, Roien LA. Bedre Seksualundervisning – Sex & Samfund (Improvement of sexual health education). [in Danish]. 2010; Copenhagen, Denmark: Sex & Samfund.

- Chambers R, Boath E, Chambers S. Young people's and professionals’ views about ways to reduce teenage pregnancy rates: to agree or not agree. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2002; 28: 85–90.

- Sex & Samfund, Bedre Seksualundervisning (Danish organization for improving sexual education). [in Danish]. [cited 2015 Aug 20]. Available from: http://www.sexogsamfund.dk/Default.aspx?ID=25947.

- Krueger RA. Designing and conducting focus group interviews. 2002 [cited 2015 Mar 6]. Available from: http://www.eiu.edu/~ihec/Krueger-FocusGroupInterviews.pdf.

- Malterud K. Kvalitative metoder i Medisinsk forskning – en innføring. 2.utgave. (Qualitative methods in medical research – a introduction). 2003; Oslo, Norway: Universtetsforlaget.

- Barüske H Grönland. Kultur und Landschaft am Polarkreis (Greenland. Culture and Landscape at the Arctic Circle). 1990; Köln: DuMont Buchverlag.

- Riel J. Myter og sagn fra Grønland. Første og anden samling (Myths and legends from Greenland. First and second edition). 2004; Viborg: Nørhaven Book.

- Gesink D, Rink E, Montgomery-Andersen R, Mulvad G, Koch A. Developing a culturally competent and socially relevant sexual health survey with an urban Arctic community. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2010; 69: 25–37.

- Rink E, Gesink Law D, Montgomery-Andersen R, Mulvad G, Koch A. The practical application of community-based participatory research in Greenland: initial experiences of the Greenland Sexual Health Study. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2009; 68: 405–13.

- PAARISA. INUK (Autumn 2006). Facts about sex pilots. [in Danish]. p. 10 [cited 2015 Aug 14]. Available from: http://old.paarisa.gl/media/21932/2006_02_paarisa_inuk_mig_og_min_krop.pdf.

- Arctic FOXY – main homepage. [cited 2015 Aug 20]. Available from: http://arcticfoxy.com/retreat/.

- Arctic FOXY – About us. [cited 2015 Aug 20]. Available from: http://arcticfoxy.com/about-us/.

- Lys C, Reading C. Coming of age: how young women in the Northwest Territories understand the barriers and facilitators to positive, empowered, and safer sexual health. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2012; 71 18957, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v71i0.18957.