Abstract

The use of abdominal angiography and transcatheter embolization has increased rapidly in the last few decades. Although improvement in angiographic techniques has made the procedure safe, ischemic colitis is a rare but potentially dreadful complication. We report a case of a 51-year-old woman who developed ischemic colitis following aortography, demonstrating that such angiographic studies may produce substantial morbidity.

Acute mesenteric ischemia, which accounts for 1–2% of gastrointestinal illnesses (Citation1), occurs as a result of either changes in systemic circulation or anatomic or functional changes in local mesenteric vasculature. The clinical scenario can range from transient ischemia to a necrotising gangrenous bowel with sepsis and death (Citation2, Citation3). Diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, heart failure, peripheral arterial disease, various drugs such as digoxin, hypercoagulability, low cardiac output states, severe atherosclerosis, and advanced age are among the well-known risk factors (Citation2–(Citation4)). Ischemic colitis is also a common complication of aortic surgeries such as repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm (Citation3); however, angiographic procedures, such as abdominal aortography, are among the rare causes (Citation5). We report a case of a colonic ischemia following aortography, demonstrating that such angiographic studies may result in substantial morbidity.

Case report

A 51-year-old postmenopausal woman, admitted to hospital for a 2-week history of subacute right flank pain, was found to have right renal angiomyolipoma on computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis. Past medical history was significant for hypertension treated with lisinopril, allergic rhinitis, and osteoarthritis. She did not smoke or drink alcohol. A percutaneous transfemoral abdominal aortography was performed using ioversol (non-ionic iodinated contrast) for prophylactic embolization of the artery supplying the angiomyolipoma so as to prevent bleeding complications. Selective angiography was performed in multiple projections including the origin of the right renal artery and infrarenal abdominal aorta to study the lower pole of the right kidney where the angiomyolipoma was located. However, embolization could not be performed owing to the inability to isolate a feeding vessel to the tumor. Twelve hours after the procedure, the patient complained of progressively worsening diffuse abdominal pain and bright red rectal bleeding.

On examination, she had a blood pressure of 117/63 mm Hg, heart rate of 94/min, respiration of 16/min, and temperature of 98.1°F. Abdominal examination revealed normal bowel sounds, soft abdomen without any distention, and tenderness over the periumbilical region and left upper quadrant. There was no rebound tenderness. Digital rectal examination showed stool mixed with bright red blood but no hemorrhoids or mass. The remainder of the examination was unremarkable. Laboratory studies included: white blood cell 10,600/μl with 80% granulocytes, hemoglobin 14.4 g/dl, and platelet count 232,000/μl. The glucose, lactate, amylase, lipase, coagulation profile, and liver and renal function tests were all within normal limits.

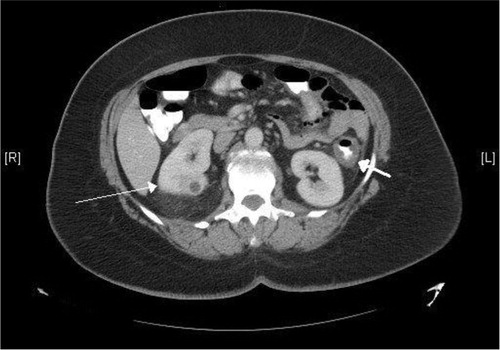

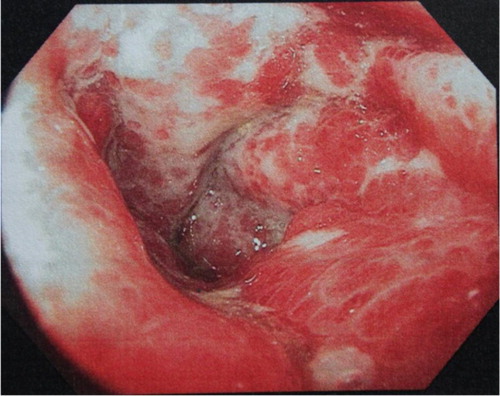

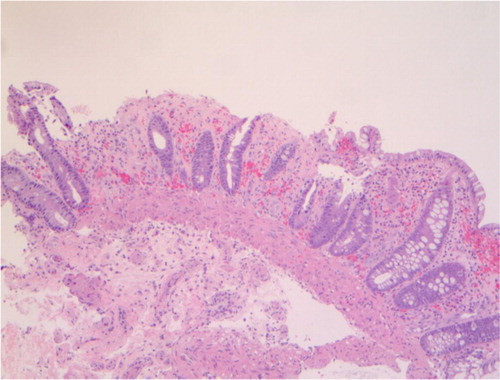

She was given nil-by-mouth and started on normal saline infusion, intravenous metronidazole, ciprofloxacin, and morphine as needed. She continued to have abdominal pain and multiple bloody bowel movements over the next 2 days. A CT of the abdomen and pelvis showed thickening of a long segment of colon spanning the distal transverse to the proximal sigmoid colon (). A colonoscopy showed edematous, erythematous, and friable mucosa overlying the splenic flexure (). Biopsy of the affected area showed focal glandular dropout, small glands with mucin depletion, denudation of surface epithelium, stromal hemorrhage, and fibrosis, thus confirming a diagnosis of ischemic colitis (). She remained hemodynamically stable throughout the course of her illness and continued to improve over the subsequent 4–5 days. She was discharged on the tenth hospital day.

Discussion

Aortography can be associated with distal arterial occlusion in 5.7% of cases after abdominal aortography and 18.2% after thoracic aortography (Citation6). Embolic complications from angiographic procedures mainly involve the lower extremities, and rarely the gastrointestinal tract (0.3–0.7% cases of aortography) (Citation5, Citation7). However, the use of abdominal angiography and transcatheter embolization has increased rapidly in the last few decades; hence, it is important to be aware of the potential complications.

Different mechanisms proposed to explain the development of the ischemic bowel injury following angiography include the toxic effect of contrast dye, injecting the dye into the intimal layer, embolization of the atheromatous debris to the mesenteric arteries, and micro-cholesterol embolization syndrome of minor vessels (Citation8). The possibility and the extent of ischemic injury depend on several factors such as the presence of preexisting arterial disease or atherosclerosis, and technical aspects of the procedure. A study has shown that the presence of the stenosis of major arteries prior to the procedure can result in complete occlusion and bowel infarction after the procedure (Citation9). It has also been shown that the incidence of intimal injury increases with superselective catheterization (Citation10). The difference in the length of the catheter, and the nature, concentration and amount of the contrast material used can also influence the incidence of arterial occlusion (Citation6, Citation11).

Ischemic colitis has usually been reported in elderly patients with diffuse atherosclerotic disease and multiple underlying comorbidities, however, it has also been reported in younger patients (Citation12). To our knowledge, the youngest reported case was a 41-year-old patient with massive intestinal infarction after angiography (Citation8). Although variable, it usually occurs 24–48 hours after angiography (Citation8). Even though the clinical features vary with the severity, most cases present with sudden, crampy abdominal pain, associated with diarrhea, which is usually bloody. The rectal bleeding is bright red to maroon, and is usually scant. Significant rectal bleeding requires searching for an alternate diagnosis. There is mild to moderate tenderness over the affected bowel, and peritoneal signs are only seen in severe cases. Rectal examination shows heme-positive stool. The patient is usually hemodynamically stable except in advanced cases when they can be acidotic and anuric (Citation2).

Ischemic bowel injury can present diagnostic challenges; while some patients might have a fulminant course with sepsis and death, others may be asymptomatic. Although abdominal pain and diarrhea are the usual presenting symptoms, patients can present without these symptoms, thus delaying timely diagnosis. A case of postangiography ischemic bowel injury presenting with anuria and general deterioration in the absence of abdominal pain has been reported (Citation13). This highlights the complexity of such cases. Severe cases of postangiography mesenteric infarctions often have fatal outcomes. In one study, more than of the half patients died reflecting the high mortality (Citation8). Therefore, a high suspicion of index and prompt investigation in the appropriate clinical context is essential for prompt diagnosis.

Leukocytosis is often present, which along with lactic acidosis, might indicate an advanced disease. Although abdominal radiograph findings such as thumb printing, ileus, and free air may be suggestive, CT scan of the abdomen is the diagnostic imaging modality of choice. CT scan shows bowel wall thickening, and colonic fat stranding, with or without pericolic fluid collection. Colonoscopic findings such as erythematous, edematous and friable mucosa, and consistent histopathological features can confirm the diagnosis, as in our patient (Citation2).

Treatment of ischemic colitis largely depends on the clinical scenario and the severity. A mild case of ischemic colitis can be managed with bowel rest, intravenous fluids, and empiric antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin and metronidazole (Citation14). Timely initiation of therapy, as in our patient, can likely prevent further deterioration. Patients requiring prolonged bowel rest, and those who are not surgical candidates should be started on parenteral nutrition (Citation15). Close clinical monitoring can identify any impending complication. Worsening abdominal pain, intractable vomiting and severe bloody diarrhea, free intraperitoneal air, and extensive gangrene on colonoscopy are indications to perform surgery. A total of 20% of cases undergo surgery; such patients have mortality as high as 60–80% (Citation16–(Citation18)).

The possibility of complications from the angiographic procedure warrants that it should be performed judiciously, more so in high-risk patients (19). Intimal injuries can be minimized with gentle manipulation of guide wires and catheters, use of flexible tipped wires and end-hole-only catheters (20). Finally, patient education and careful monitoring for symptoms and signs of such complications are important for timely diagnosis.

Conclusion

Vascular injury such as ischemic colitis is rare but a potential complication of aortography. Careful patient selection and caution during the procedure might reduce the complication. Postprocedural monitoring, patient education, and timely evaluation can prevent further deterioration and associated morbidity and mortality. Ischemic bowel injury can have protean and atypical manifestations; hence, a high index of suspicion is important.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study.

References

- Schneider TA, Longo WE, Ure T, Vernava AM 3rd. . Mesenteric ischemia. Acute arterial syndromes. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994; 37(11): 1163–74.

- Theodoropoulou A, Koutroubakis IE. Ischemic colitis: Clinical practice in diagnosis and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2008; 14(48): 7302–8.

- Gandhi SK, Hanson MM, Vernava AM, Kaminski DL, Longo WE. Ischemic colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996; 39(1): 88–100.

- Cubiella Fernandez J, Nunez Calvo L, Gonzalez Vazquez E, Garcia Garcia MJ, Alves Perez MT, Martinez Silva I, etal. Risk factors associated with the development of ischemic colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010; 16(36): 4564–9.

- Szilagyi DE, Smith RF, Macksood AJ, Eyler WR. Abdominal aortography: Its value and its hazards. AMA Arch Surg. 1962; 85(1): 25–40.

- Kottke BA, Fairbairn JF, Davis GD. Complications of aortography. Circulation. 1964; 30: 843–7.

- Lang EK. A survey of the complications of percutaneous retrograde arteriography. Radiology. 1963; 81(2): 257–63.

- Levy PJ, Manny J. Mesenteric infarction following angiography. Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1993; 27(9): 689–95.

- Sumner DS. Successful revascularization of mesenteric infarction following aortography. Am Surg. 1977; 43(11): 743–50.

- Sigstedt B, Lunderquist A. Complications of angiographic examinations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1978; 130(3): 455–60.

- Sewell RA, Killen DA, Foster JH. Small bowel injury by angiographic contrast medium. Surgery. 1968; 64(2): 459–65.

- Binns JC, Isaacson P. Age-related changes in the colonic blood supply: Their relevance to ischaemic colitis. Gut. 1978; 19(5): 384–90.

- Gaines PA, Cumberland DC, Kennedy A, Welsh CL, Moorhead P, Rutley MS. Cholesterol embolisation: A lethal complication of vascular catheterisation. Lancet. 1988; 1(8578): 168–70.

- Brandt LJ, Boley SJ. AGA technical review on intestinal ischemia. American Gastrointestinal Association. Gastroenterology. 2000; 118(5): 954–68.

- Baixauli J, Kiran RP, Delaney CP. Investigation and management of ischemic colitis. Cleve Clin J Med. 2003; 70(11): 920–1, 925–6, 928–30 passim.

- Bjorck M, Troeng T, Bergqvist D. Risk factors for intestinal ischaemia after aortoiliac surgery: A combined cohort and case-control study of 2824 operations. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1997; 13(6): 531–9.

- Corder AP, Taylor I. Acute mesenteric ischaemia. Postgrad Med J. 1993; 69(807): 1–3.

- Longo WE, Ballantyne GH, Gusberg RJ. Ischemic colitis: Patterns and prognosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992; 35(8): 726–30.

- Pollard JJ, Nebesar RA. Abdominal angiography. N Engl J Med. 1968; 279(19): 1035–42. contd.

- Hunt TH, Gelfand DW. Complications of gastrointestinal radiologic procedures: III. Complications of diagnostic and interventional angiography. Gastrointest Radiol. 1981; 6(1): 57–67.