Abstract

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a phenomenon of cutaneous ulceration where etiology is not well understood. About half of the cases have an associated extracutanoeus manifestation or associated systemic diseases. Most commonly associated systemic disorders include inflammatory bowel disease, hematologic malignancies, autoimmune arthritis, and vasculitis. We are reporting a case where pyoderma gangrenosum has presenting features for ulcerative colitis.

A 34-year-old African American female, who is a member of the emergency medical service, presented with multiple painful ulcers on her lower back, buttocks, and right thigh for 1 week. Her medical history was significant for intermittent diarrhea for the past 2 years, which responded to a gluten-free diet. Two weeks prior to the current admission, she was seen in the emergency department for painful, draining ulcers on the mucosal surface of her lips and was treated with clindamycin. One week later, she developed pustules, which resulted in deep painful ulcers. She denied genital ulcers, discharge, or recurrent mouth ulcers. In concurrence with ulcers, she developed lower abdominal pain with non-bloody diarrhea. Diarrheal episodes were similar to her prior episodes but more severe. On admission, she also reported a non-productive cough without dyspnea, fever, or chest pain. She denied recent travel, weight loss, sexually transmitted disease, irradiation, or use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, alcohol, or tobacco. She was in the middle of her menstrual cycle.

Apart from mild lower abdominal pain, she was not in acute distress. She had sinus tachycardia with a heart rate in 130 s and blood pressure at her baseline. Her abdomen was soft, non-distended, good bowel sounds, and mild tenderness in bilateral lower quadrants without rebound. Lungs were clear on auscultation and resonant to percuss. On cardiac auscultation, a grade 2/6 ejection systolic murmur was appreciated. Rectal examination was deferred due to painful ulcers in the perianal area but diarrheal stools were positive for occult blood. Her ulcers had well-defined erythematous margins with a bluish hue. There were some satellite pustules measuring about 1 cm in diameter ().

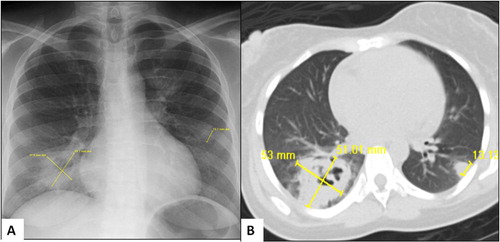

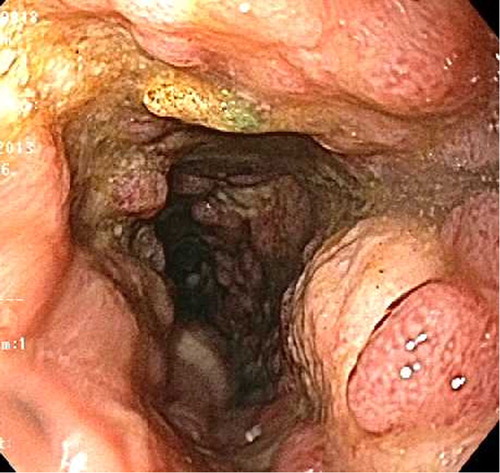

Her admission labs showed white cell count of 20,000/cmm and 80% neutrophils, 28% of them being immature. Platelets 700 K/cmm, hemoglobin 8 g/dL and hematocrit 23%, mean corpuscular volume 85 fL, low iron saturation and total iron binding capacity, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 82 mm/hr. Her serum albumin was 1.8 g/dL and globulin level was 4.5 g/dL. Urine was negative for protein or casts. Chest radiograph showed three subpleural nodules (A), one of them had cavities which were better defined on computed tomography (B). She was admitted to the general medical floor, initiated on fluid resuscitation, empirical intravenous antibiotics and valacyclovir for presumed herpes simplex with superinfection. For clinical suspicion of ulcerative colitis, sigmoidoscopy was performed, which demonstrated endoscopic evidence of ulcerative colitis (). Further work-up suggested mildly positive p-ANCA, negative tuberculin skin test (was negative 2 months previous, when done for a work physical examination), and HIV. Stool for Clostridium difficile (polymerase chain reaction assay for toxin-producing gene), Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, or Escherichia coli 0157, set of blood cultures, wound culture for herpes simplex, transglutaminase antibodies were negative.

Fig. 2 Chest radiography (A) showing pleural-based nodules which are better visualized on computed tomography with cavity in the right lower lobe (B).

Fig. 3 Sigmoidoscopic examination demonstrating friable deeply ulcerated mucosa in sigmoid and descending colon.

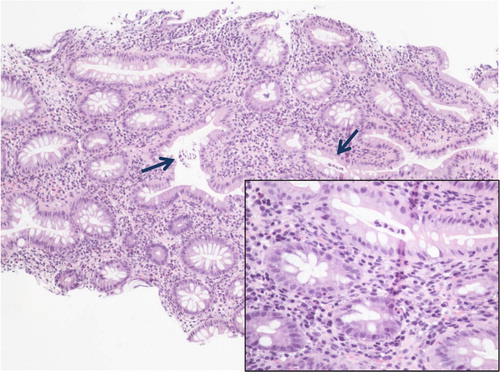

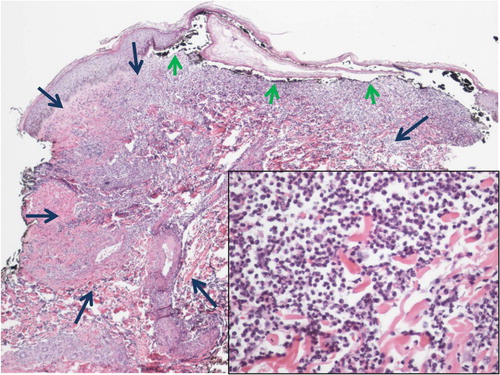

The patient was started on prednisone and mesalamine while continuing on ciprofloxacin and metronidazole. Before starting to feel better, the patient worsened clinically and white cell count peaked to 45,000/cmm. Histopathology of colonic biopsy showed ulceration, focal areas of scarring, mild crypt distortion, mild acute cryptitis, increased chronic inflammation, and small crypt abscesses without granulomas consistent with ulcerative colitis (). Punch biopsy from her thigh showed necrotizing suppurative inflammation associated with ulceration and focal secondary perivascular acute inflammation consistent with pyoderma gangrenosum (). There was no direct immunefluorescence evidence of vasculitis. Three weeks after discharge, the patient continued to improve clinically and is scheduled for a bronchoscopic biopsy for further evaluation of pulmonary nodules. At 6 weeks, a follow-up chest radiograph showed that thin-walled cavity and inflammatory changes were resolved.

Fig. 4 Colon biopsy showing crypt distortion and increased chronic inflammation within the lamina propria. Arrows denote two small crypt abscesses (inset: small crypt abscess and mixed inflammatory infiltrate within the lamina propria including neutrophils).

Fig. 5 Low power of right anterior proximal thigh skin biopsy showing changes of pyoderma gangrenosum. The center of the lesion (denoted by long blue arrows) shows a dense neutrophilic infiltrate with leukocytoclasia and dermolysis (inset: high power image of inflammatory infiltrate). Short green arrows point to undermining of epidermis by inflammatory infiltrate to the left and cutaneous ulceration to the center and right.

Discussion

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a cutaneous ulcerative disorder of unknown etiology. Histopathologically, it is a neutrophilic dermatosis which presents as deep purulent ulcers with well-defined and often undermining margins with a violaceous hue. Multiple phenotypes of pyoderma gangrenosum have been described; ulcerative form is the most common type (Citation1). Other phenotypes include pustular, bullous, and vegetative. The most common location of pyoderma gangrenosum is in the lower extremities (Citation2, Citation3) but any part of the body can be involved. In inflammatory bowel disease, pyoderma gangrenosum is reported in about 3% patients in ulcerative colitis and more often in patients with Crohn's disease (Citation4). In the general population, pyoderma gangrenosum occurrence is 3–10 cases per million.

Exact pathogenesis of pyoderma gangrenosum is unknown. It has been described both as a cutaneous disorder of uncertain etiology (Citation5) and a cutaneous manifestation of systemic disorders. About half of the cases of pyoderma gangrenosum have an associated systemic disorder (Citation6). Most common systemic disorders include inflammatory bowel disease, hematologic malignancies, autoimmune arthritis, and vasculitis. As a cutaneous disorder, visceral involvement is reported often. Visceral lesions are similar to cutaneous lesions (sterile neutrophilic infiltration with granuloma formation) and have been reported in lungs, liver, bone, spleen, major airway, heart, and so on (Citation7–(Citation10)).

Pulmonary nodules have been reported in cases of pyoderma gangrenosum. The most likely differential diagnosis is granulomatosis with polyangiitis. In the cases reported here, the patient had no evidence of renal or upper airway involvement and was tested negative for c-ANCA. The combination of lack of clinical findings and c-ANCA make granulomatosis with polyangiitis very unlikely in our patient. As per a literature review performed in 2011, 11 cases of pulmonary nodules with or without cavitation have been reported in pyoderma gangrenosum (Citation11). Reported pulmonary nodules are usually subpleural, unilateral or bilateral, no predilection to upper lobe, may or may not have sterile central caseation leading to cavity formation. Lung biopsies of these lesions show non-specific necrotizing inflammatory granulomas with neutrophilic infiltration (Citation11).

The main stay in the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum is systemic glucocorticoids. A very high recurrence rate is reported (Citation3–(Citation12)) and about 5% of cases are refractory to glucocorticoids that have been successfully treated with cyclosporine A, tacrolimus, or a biological agent (Citation13, Citation14). The treatment of cutaneous lesions improves visceral lesions also (Citation2). Our patient was continued on mesalamine; oral prednisone was being tapered down without worsening of cutaneous lesions and inflammatory changes in the lung cavity were resolved.

In conclusion, pyoderma gangrenosum can be the presenting feature in ulcerative colitis. Based on prior reports of histopathological similarity in skin and lung lesions and response to steroid treatment, pulmonary nodules could be assumed a spectrum of extraintestinal manifestation of ulcerative colitis. In clinical practice, granulomatosis with polyangiitis should be considered as differential diagnosis as up to 14% of the patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis have cutaneous lesions (Citation15). Lack of vasculitis in biopsy and immune deposits favor pyoderma gangrenosum, whereas c-ANCA is highly specific for active granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Citation16).

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the following clinicians for their input into the management of this interesting case: Niraj Jani MD (gastroenterology and hepatology), Mark H. Lowitt MD (dermatology), Charles Haile MD (infectious diseases), Robert Ferguson MD (internal medicine), and Robert A. Palermo MD (pathology).

References

- Powell FC, Su WP, Perry HO. Pyoderma gangrenosum: Classification and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996; 34: 395–409; Quiz 410–2.

- Duarte AF, Nogueira A, Lisboa C, Azevedo F. [Pyoderma gangrenosum – clinical, laboratory and therapeutic approaches. Review of 28 cases]. Dermatol Online J. 2009; 15: 3.

- Vidal D, Puig L, Gilaberte M, Alomar A. Review of 26 cases of classical pyoderma gangrenosum: Clinical and therapeutic features. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004; 15: 146–52.

- Ozdil S, Akyuz F, Pinarbasi B, Demir K, Karaca C, Boztas G, etal. Ulcerative colitis: Analyses of 116 cases (do extraintestinal manifestations effect the time to catch remission?). Hepatogastroenterology. 2004; 51: 768–70.

- von den Driesch P. Pyoderma gangrenosum: A report of 44 cases with follow-up. Br J Dermatol. 1997; 137: 1000–5.

- Mlika RB, Riahi I, Fenniche S, Mokni M, Dhaoui MR, Dess N, etal. Pyoderma gangrenosum: A report of 21 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2002; 41: 65–8.

- Vadillo M, Jucgla A, Podzamczer D, Rufi G, Domingo A. Pyoderma gangrenosum with liver, spleen and bone involvement in a patient with chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia. Br J Dermatol. 1999; 141: 541–3.

- Kruger S, Piroth W, Amo Takyi B, Breuer C, Schwarz ER. Multiple aseptic pulmonary nodules with central necrosis in association with pyoderma gangrenosum. Chest. 2001; 119: 977–8.

- Kanoh S, Kobayashi H, Sato K, Motoyoshi K, Aida S. Tracheobronchial pulmonary disease associated with pyoderma gangrenosum. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009; 84: 555–7.

- Lebbe C, Moulonguet-Michau I, Perrin P, Blanc F, Frija J, Civatte J. Steroid-responsive pyoderma gangrenosum with vulvar and pulmonary involvement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992; 27: 623–5.

- Batalla A, Perez-Pedrosa A, Garcia-Doval I, Gonzalez-Barcala FJ, Roson E, de la Torre C. [Lung involvement in pyoderma gangrenosum: A case report and review of the literature]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2011; 102: 373–7.

- Riahi I, Mokni M, Haouet S, Cherif F, El Euch D, Azaiz MI, etal. [Pyoderma gangrenosum. 15 cases]. Ann Med Interne (Paris). 2001; 152: 3–9.

- Lopez de Maturana D, Amaro P, Aranibar L, Segovia L. [Pyoderma gangrenosum: Report of 11 cases]. Rev Med Chil. 2001; 129: 1044–50.

- Deregnaucourt D, Buche S, Coopman S, Basraoui D, Turck D, Delaporte E. [Pyoderma gangrenosum with lung involvement treated with infliximab]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2013; 140: 363–6.

- Daoud MS, Gibson LE, DeRemee RA, Specks U, el-Azhary RA, Su WP. Cutaneous Wegener's granulomatosis: Clinical, histopathologic, and immunopathologic features of thirty patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994; 31: 605–12.

- Rao JK, Weinberger M, Oddone EZ, Allen NB, Landsman P, Feussner JR. The role of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (c-ANCA) testing in the diagnosis of Wegener granulomatosis. A literature review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1995; 123: 925–32.