Abstract

Fulminant hepatic failure (FHF) is a relatively rare manifestation of Hodgkin's lymphoma. Clinical features, laboratory findings, and imaging of the liver are usually inconclusive, and liver biopsy may be required for confirmation. We present a case of an FHF in a woman 1 week after the diagnosis of Hodgkin's lymphoma. Chemotherapy could not be instituted due to hepatic encephalopathy and other complications. Autopsy revealed diffuse infiltration of the liver parenchyma. This case illustrates the importance of early diagnosis and institution of chemotherapy, which may reverse the liver failure.

Fulminant hepatic failure (FHF) is defined as the development of coagulopathy and encephalopathy within 8 weeks of the onset of liver dysfunction in patients without pre-existing liver disease (Citation1). The common causes of FHF include acute viral hepatitis, drugs, toxins, ischemic hepatitis, and autoimmune hepatitis. Occasionally, the worsening of pre-existing hepatic condition may also mimic FHF (Citation2). Hematologic malignancies are infrequent (0.44%) but important causes (Citation3, Citation4), because liver transplant is contraindicated in this situation, hence early diagnosis and initiation of chemotherapy are only hopes to alter the outcomes.

Case description

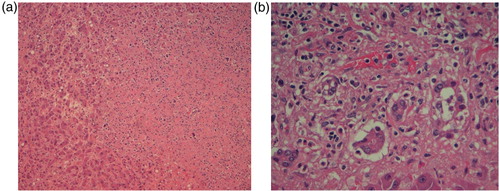

A 63-year-old woman presented with persistent high-grade fever and night sweats for 1 week. Two weeks prior to the presentation, the patient was diagnosed with nodular sclerosing Hodgkin's lymphoma (a and b) stage IV on her lymph node and bone marrow biopsy. She was planned to start chemotherapy but had to be admitted for further workup. Medical history was significant for daily alcohol consumption for the past 20 years.

Fig. 1 (a) High power view of Level 7 lymph node from the neck showing atypical cells, some of which are multinucleated and consistent with Reed–Sternberg (RS) cells although not typical. (b) Immunohistochemical stain showing RS cells positive for CD30.

Examination revealed a fully alert woman oriented to time, place, and person. She had a temperature of 39.2°F, heart rate of 101/min, and mild icterus. There was no palpable lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, or any stigmata of chronic liver disease. Laboratory tests revealed white cell count (WBC) of 3.8×109/L, hemoglobin of 8.3 g/dl, platelet count of 60×109/L, total bilirubin of 1.7 mg/dl, direct bilirubin level of 0.9 mg/dl, alanine transaminase (ALT) of 35 IU/L, aspartate transaminase (AST) of 28 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) of 231 IU/L, prothrombin time (PT) of 16.9 sec (normal 10.2–11.7 sec), international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.5, partial thromboplastin time (PTT) of 36 sec (normal 25–33 sec), albumin of 1.3 g/dl, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) of 156 IU/L (normal 94–202 IU/L). Blood cultures, urine culture, and sputum culture were sent, which subsequently turned out to be negative. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis did not reveal any source of infection. She was empirically started on intravenous vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam. Serological tests for Cytomegalovirus, Epstein–Barr virus, and Cryptococcus were also negative.

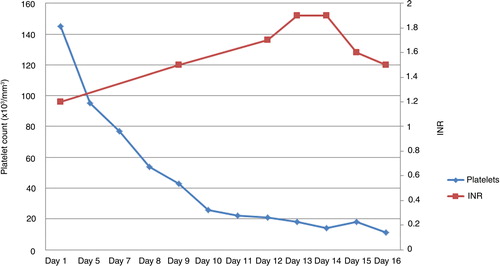

Clinical course was complicated by the development of grade III encephalopathy and worsening pancytopenia. CT scan and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain were normal. Lumbar puncture was avoided due to severe thrombocytopenia (11×109/L). Liver function tests revealed a direct bilirubin of 9.6 mg/dl, total bilirubin of 15.2 mg/dl, INR of 1.9, AST of 48 IU/L, ALT of 48 IU/L, and ALP of 170 IU/L (). Ultrasonogram and Doppler imaging of the abdomen revealed mild splenomegaly with no ascites, normal hepatic size, echo texture, and normal hepatic veins. Serological studies for hepatitis A, B, and C viruses and human immunodeficiency virus were negative. Blood alcohol, acetaminophen, salicylate levels, α-feto protein level, and urine toxicology were all negative. Antinuclear antibody was positive (1:80, speckled), but anti-mitochondrial and anti-smooth muscle antibodies were negative.

Table 1 Laboratory parameters showing deterioration of coagulation parameters

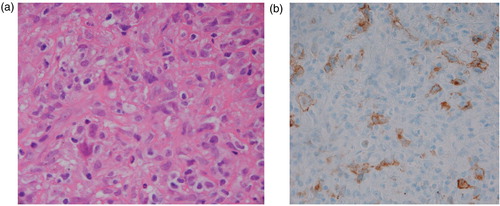

A possibility of advanced Hodgkin's disease (HD) infiltrating the liver was entertained. A liver biopsy was withheld due to significant thrombocytopenia, coagulopathy (), and encephalopathy. She was determined to be a poor candidate for emergent liver transplantation because of the history of HD and alcohol abuse. She was also determined to be a poor candidate for chemotherapy because of hepatic encephalopathy. After a lengthy discussion with family members, given the poor prognosis from FHF and advanced lymphoma, the patient was transitioned to comfort cares and passed away shortly thereafter. An autopsy revealed lymphocyte-depleted HD (in contrast to earlier bone marrow biopsy showing nodular sclerosing type) extensively involving liver, spleen, cervical, supraclavicular, mediastinal, and retroperitoneal lymph nodes. The pathologic examination of the liver showed small nodules of cancer as well as infiltrative neoplastic pattern characterized by areas of necrosis, characteristic Reed–Sternberg cells, and areas of hypocellularity in an eosinophilic fibrillar background (a and b).

Discussion

The patient reported here developed FHF soon after the diagnosis of HD. The patient did not have any history of liver disease and autopsy did not reveal any evidence of chronic liver disease, thus confirming that hepatic infiltration by HD was the cause of FHF. Hepatic involvement is seen in approximately one-fourth of the cases of lymphoma, which ranges from a mild hepatic dysfunction to FHF (Citation5). Few mechanisms have been implicated for hepatic dysfunction in lymphoma, including the infiltration of the liver parenchyma, biliary tree, or hepatic vasculature. Also, vanishing bile duct syndrome resulting from cytokine release with interlobular bile duct destruction and portal fibrosis, and rarely a paraneoplastic syndrome with no liver infiltration have been described (Citation2, Citation5) (Citation6). In cases of extensive infiltration of the liver parenchyma, as in the reported case, the obstruction of small vessels by neoplastic cells leading to liver anoxia has been implicated as the cause of hepatic failure.

Hepatic involvement on staging laparotomy has been reported more frequently in cases of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (16–22%) and leukemia as compared to HD (5–8%); however, FHF is a rare complication (0.44%) (Citation3, Citation4). Although all types of HD have been implicated, lymphocyte-depleted HD seems to be the most common type associated with hepatic involvement (Citation7). Hepatic involvement may occur at various stages of HD. Although it is usually seen during advanced stages, FHF can be the presenting feature of HD on rare occasions (Citation2, Citation6) (Citation8, Citation9). The clinical picture is usually indistinguishable from other causes of FHF, and diagnosis may only be made at autopsy. Therefore, a core biopsy of liver is required for confirmation (Citation10). Less than 10% of percutaneous liver biopsies show liver infiltration by lymphoma because the Reed–Sternberg cells can have a patchy distribution. Laparoscopic-guided biopsies and immunohistochemistry may improve the diagnostic yield (Citation4, Citation9). The presence of mononuclear variants of Reed–Sternberg cells is enough for a diagnosis of hepatic involvement in an established case of HD. However, classical multi-nucleated Reed–Sternberg cells is required if liver is the only organ involved (Citation8).

Early diagnosis is important as early institution of chemotherapy may reverse the hepatic dysfunction. Delay in diagnosis is common because of normal liver imaging, as in the reported case, its rarity, and lack of awareness. With the development of FHF, the prognosis is dismal despite treatment. Coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia increases the risk of liver biopsy whereas hepatic failure increases the complications from chemotherapy. Nonetheless, the liver biopsy and chemotherapy should still be considered and discussed with the patient and the family. One of the studies showed that in select cases, there may be no increase in morbidity or mortality due to the liver biopsy with the utilization of fresh frozen plasma and platelet transfusion as clinically indicated (Citation10).

Although liver transplant remains the mainstay of treatment for FHF from other causes, it is contraindicated in hematological malignancy (Citation2). In patients with disseminated liver involvement, combined chemotherapy may still be the treatment of choice. At least partial response to the treatment has been observed in many cases when used early on (Citation2, Citation5). The most appropriate chemotherapy regimen for HD with liver failure remains uncertain as most of these drugs are associated with liver dysfunction. The use of dexamethasone, cytarabine, and cisplatin (DHAP) may be safe and effective without dose modification in patients with severe liver dysfunction (Citation6). Other regimens that may be considered include etoposide, methylprednisone, cytarabine, and cisplatin- (ESHAP) and ifosfamide-based regimens (Citation9). Radiotherapy may be beneficial in early stages to extra-hepatic sites and may improve hepatic dysfunction, especially in cases of vanishing bile duct syndrome (Citation6). The prognosis is usually poor with a mean survival of 6 days (range 1–51 days) after admission in a case series (n=18, of which three cases were from HD). All HD cases died because of sepsis and multiorgan failure (Citation10). In most reported cases, patients either succumb to FHF, multiorgan failure, or sepsis as a complication of chemotherapy-induced immunosuppression (Citation6). There are a few reports of HD with FHF where liver transplantation was lifesaving, however, HD recurred in the transplanted liver (Citation6, Citation11). Early diagnosis and initiation of chemotherapy before the development of FHF can improve outcomes in select cases (Citation12).

HD infiltrating the liver frequently represents lymphocyte-depleted extranodal HD, which is expected to have worse prognosis. Given their very aggressive course, whether HD with FHF represents a unique subset of disease with different pathobiology remains speculative. In the reported case, a nodular sclerosis HD was diagnosed in a bone marrow biopsy, whereas evaluation at autopsy demonstrated lymphocyte-depleted HD. Apart from the possibility that a bone marrow biopsy is imperfect for the diagnosis of lymphoma subtypes, we do not have a good explanation for this phenomenon.

Conclusion

Hepatic dysfunction in HD patient may reflect involvement of liver by lymphoma. Given the risk of FHF, which may preclude subsequent liver biopsy and therapy, an early liver biopsy should be considered in such patients. In HD patients with FHF, who cannot undergo a liver biopsy, whether an empiric use of chemotherapy alters the outcome is unclear (given the rarity of this condition). If a decision is made to treat such patients, patients may be treated with dose-adjusted chemotherapy. The optimal chemotherapy regimen remains unclear but drugs metabolized by liver such as adriamycin and vinblastine needs dose reduction based on the degree of hyperbilirubinemia.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study.

References

- Trey C, Davidson CS. The management of fulminant hepatic failure. Prog Liver Dis. 1970; 3: 282–98.

- Dourakis SP, Tzemanakis E, Deutsch M, Kafiri G, Hadziyannis SJ. Fulminant hepatic failure as a presenting paraneoplastic manifestation of Hodgkin's disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999; 11: 1055–8.

- Morali GA, Rozenmann E, Ashkenazi J, Munter G, Braverman DZ. Acute liver failure as the sole manifestation of relapsing non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001; 13: 1241–3.

- Woolf GM, Petrovic LM, Rojter SE, Villamil FG, Makowka L, Podesta LG, etal. Acute liver failure due to lymphoma. A diagnostic concern when considering liver transplantation. Dig Dis Sci. 1994; 39: 1351–8.

- Vardareli E, Dündar E, Aslan V, Gülbas Z. Acute liver failure due to Hodgkin's lymphoma. Med Princ Pract. 2004; 13: 372–4.

- Hong FS, Smith CL, Angus PW, Crowley P, Ho WK. Hodgkin lymphoma and fulminant hepatic failure. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010; 51: 947–51.

- Mauch PM, Kalish LA, Kadin M, Coleman CN, Osteen R, Hellman S. Patterns of presentation of Hodgkin disease. Implications for etiology and pathogenesis. Cancer. 1993; 71: 2062–71.

- Ortin X, Rodriguez-Luaces M, Bosch R, Lejeune M, Font L. Acute liver failure as the first manifestation of very late relapsing of Hodgkin's disease. Hematol Rep. 2010; 2: e5.

- Thompson DR, Faust TW, Stone MJ, Polter DE. Hepatic failure as the presenting manifestation of malignant lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma. 2001; 2: 123–8.

- Rowbotham D, Wendon J, Williams R. Acute liver failure secondary to hepatic infiltration: A single centre experience of 18 cases. Gut. 1998; 42: 576–80.

- Abdulkader I, Fraga M, González-Quintela A, Caparrini A, Bello JL, Galban C, etal. Prolonged survival after liver transplantation for Hodgkin's disease-induced fulminant liver failure. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005; 52: 217–19.

- Trewby PN, Portmann B, Brinkley DM, Williams R. Liver disease as presenting manifestation of Hodgkin's disease. Q J Med. 1979; 48: 137–50.