Abstract

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) is a rare multisystem microvascular disorder, which is characterized by pentad of thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, and organ dysfunction due to occlusive thrombi. The proposed pathophysiology involves an imbalance between unusually large von Willebrand factor multimers and the cleaving protease ADAMTS13. Acute pancreatitis is a well-described consequence of TTP, but TTP secondary to acute pancreatitis is a rare phenomenon. We present a patient who developed TTP due to post-ERCP pancreatitis with hematologic, cardiovascular, pulmonary, and renal complications and is the first case of this kind. Despite early initiation of therapy, the patient did not recover making it among the 10% of cases of TTP that prove fatal despite appropriate therapy.

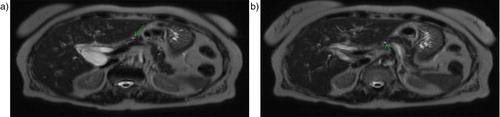

A 79-year-old woman with a history of hypertension presented to the emergency department with a 1-day history of a severe right upper quadrant and epigastric pain associated with nausea. Her examination was pertinent for normal vital signs, right upper quadrant, and epigastric tenderness without rebound tenderness. Laboratory data were pertinent for: blood urea nitrogen (BUN)=25 mg/dL, creatinine=1.19 mg/dL, aspartate amionotransferase (AST)=105 U/L, alanine amionotransferase (ALT)=51 U/L, alkaline phosphatase=42 U/L, total bilirubin=0.7 mg/dL, amylase=68 U/L, and lipase=43 U/L. Abdominal ultrasound showed common bile duct (CBD) dilation of 10 mm without evidence of a stone. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography was consistent with distal CBD stenosis (a and b).

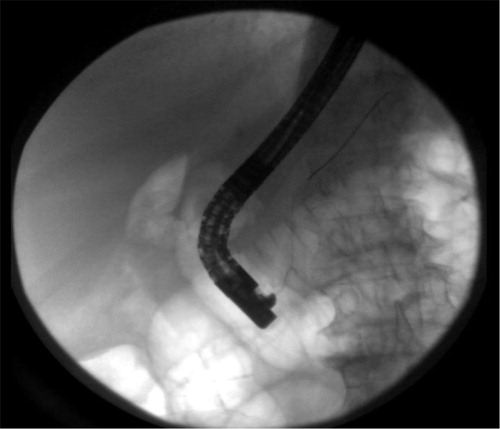

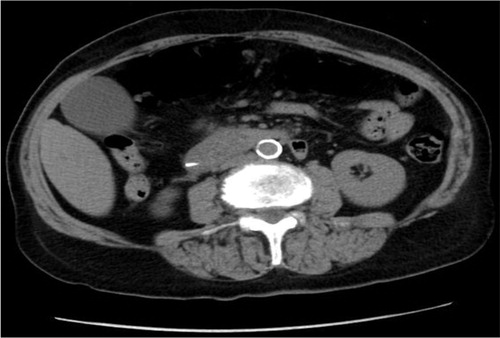

The patient underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with failure to cannulate and explore CBD. She subsequently developed worsening epigastric pain, a lipase level of 2,756 U/L and an amylase of 777 U/L consistent with acute pancreatitis. Computed tomography of the abdomen confirmed the diagnosis of post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP) (Figs. –). Further labs showed thrombocytopenia, dropping hemoglobin as well as worsening creatinine ().

Table 1 Lab trends in days: platelets count, hemoglobin, and creatinine

Hemolytic anemia workup showed: lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)=2,244 U/L, direct bilirubin=14.1 mg/dL, haptoglobin <7 mg/dL, reticulocyte count=153 K/UL, rising reticulocyte percentage from 5 to 8.1%, internal normalized ratio (INR)=1.2, partial thromboplastin time (PTT)=28 sec, fibrinogen=250 mg/dL and negative heparin-induced thrombocytopenia panel (). Peripheral blood smear showed giant platelets and schistocytes, and an ADAMTS13 level was 56% (peripheral smear picture).

Table 2 Hemolytic anemia workup

Treatment with plasma exchange (PEX) and intravenous steroids with the addition of rituximab failed to improve her platelet count. Her labs initially improved but started getting worse again. She was started on eculizumab but without any help. She ultimately developed subdural hematomas, seizures, and heart failure needing a prolonged intubation as a complication of TTP-aHUS. The patient eventually died after 35 days of unsuccessful intensive therapy.

Discussion

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) is a rare acquired or congenital disorder with an annual incidence of six cases per million (Citation1). Its pathogenesis involves an imbalance between von Willebrand factor (vWF) multimers and ADAMTS13. Large vWF multimers cause platelet activation and aggregation leading to thrombus formation. These thrombi occlude small vessels and result in organ damage. If there is a gene mutation existing congenitally leading to absent or severely deficient ADAMTS13 activity, it is called Upshaw-Shulman syndrome. Autoantibodies against ADAMTS13 leading to its decreased activity are called acquired TTP (Citation2). PEX is the first-line treatment and is effective in most of the cases. However, in secondary TTP with normal or moderately reduced ADAMTS13 activity and no evidence of ADAMTS13 inhibitor, PEX is not effective in many cases (Citation3).

Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) is a disorder characterized by complement gene mutations or anti-factor H autoantibodies (CFH) autoantibodies causing dysregulation of the alternative complement pathway. Some other mutations identified in aHUS are as follows:

Inactivating mutations of CFH (factor H), CFI (factor I), MCP (membrane cofactor protein), or thrombomodulin

Gain-of-function mutations of factor B and C3, and anti-CFH autoantibodies

But only 70% of patients will be found to have these mutations and more mutational analyses need to be done including the recent finding of mutations of diacylglycerol kinase ɛ in patients with suspected aHUS. The first-line treatment for aHUS is still PEX because there is no test available that can initially differentiate between TTP and aHUS. Sinha et al. (Citation4) demonstrated that in patients with anti-CFH antibody-mediated aHUS, the instantaneous use of PEX and immune-suppressive therapy can improve outcomes.

Eculizumab (Soliris) was approved by food and drug administration (FDA) in September 2011 for patients refractory to PEX. Mortality rate before that was 67% and has gone down a lot where four out of five patients are able to come off dialysis. To note, end-stage renal disease was the major cause of death in people surviving initial hospitalization with aHUS (Citation5).

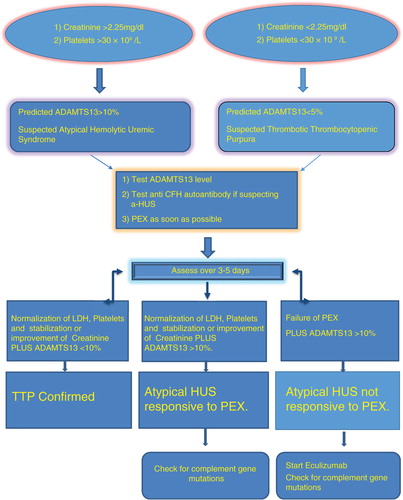

It has always been a dilemma to differentiate aHUS from TTP. In the past, TTP and aHUS have been considered a spectrum of a single disorder. Traditionally, TTP is the diagnosis when there is an involvement of central nervous system (CNS), and aHUS is the diagnosis when renal impairment is predominant. However, recent discoveries have solved this mystery by identifying the pathophysiological mechanisms. Now it is known that both these entities are in fact different disorders with distinct characteristics. Therefore, clinically, patients with TTP may have renal dysfunction and those with aHUS may develop CNS manifestations. Even though, it is now possible to differentiate these two disorders, we still do not have the capability to differentiate them at presentation. Hence, initial treatment for both these disorders is same, that is, PEX therapy.

Although a severe deficiency of the ADAMTS13 protease (<5–10%) and documented mutations of complement proteins are not required for the diagnosis of acquired TTP and aHUS, respectively, both findings in the appropriate clinical context serve to confirm the clinical diagnosis. TTP and aHUS were considered a single entity for a long time. Recently, the two conditions were found to be secondary to completely different mechanisms as explained above. Eculizumab was approved by FDA in 2011 for aHUS and has become the gold standard therapy for this. PEX was used to be the standard of treatment for both the situations. But it still remains a challenge to differentiate them and the decision has to be made on clinical judgment. ADAMTS13 can differentiate in most of the conditions but takes days to weeks to come back depending on the location. Meanwhile, starting therapy as soon as possible is really necessary to improve survival outcomes. C3, C4, and CH50 cannot be used because they are very non-specific and can be abnormal in a lot of situations. TTP seems to cause more severe thrombocytopenia, and aHUS is associated with more severe renal failure and is a leading cause of death in these patients. Diagnosis is likely to be TTP if platelet count is less than 30,000/L and creatinine is less than 2.25 mg/dL. On contrary, aHUS is the likely diagnosis if platelet count is greater than 30,000/L and creatinine is more than 2.25 mg/dL. On suspicion of TTP or aHUS, emergent treatment with PEX should be instituted but should be rethought in 3–5 days in non-responders and focus should be shifted to eculizumab. PEX should be avoided when giving eculizumab because it gets washed out ().

Pancreatitis is one of the most common and severe complications after ERCP. Multiple methods have been adopted to prevent this complication. For better insight, we need to understand the mechanism behind PEP which is thought to be due to sphincter of Oddi spasms or papillary edema leading to pancreatic drainage blockage. So, a substitute drainage pathway will decrease the chances of PEP. This led to the concept of pancreatic duct (PD) stenting. PD stenting can itself increase post-ECRP complications if there are any manipulation accidents during placement. Therefore, safety remains an important concern during prophylactic PD stent placement (Citation6, Citation7). Another way to prevent PEP is by rectal indomethacin. NSAIDs have been proposed to reduce the incidence of PEP by their anti-inflammatory action, but PD stent was the only major prevention method. Recently, a study showed that placebo had four times more PEP compared to rectal indomethacin. The incidence of the complication was 4.87% (4/82) in the study group and 20.23% (17/84) in the placebo group; this difference was significant (p=0.01). Rectal indomethacin reduced the incidence of PEP among patients at high risk of developing this complication (Citation8). A study done comparing PD stenting with placebo showed that placebo had three times more PEP incidence than patients getting PD stenting. To reconcile, any method is acceptable but PD stenting needs more expertise.

Pancreatitis is a well-known complication of TTP, but TTP-aHUS secondary to acute pancreatitis is a rare occurrence. Hosler et al. (Citation9) found that 30 out of 51 patients diagnosed with TTP had pancreatic involvement. The mechanism proposed is ischemic pancreatitis due to thrombotic occlusion of small vessels. TTP associated with pancreatitis is mostly in anecdotal data. There was a major study done in Japan in 2008 that looked at 919 patients with thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) and none of them were triggered by acute pancreatitis (Citation10). The median time from pancreatitis to the development of TTP-aHUS is 3 days which is true in our patient. Swisher et al. (Citation11) reported 5 patients and reviewed 16 cases from the literature, in which acute pancreatitis preceded clinically and laboratory signs of TTP by a median of 3 days (Citation12). In the great majority of cases, TTP develops in healthy individuals. The etiology is found in only 10% of cases. It has been associated with pregnancy, vascular disease, malignancy, and certain drugs, and the newest associations are HIV and pancreatitis (Citation1). Case reports have shown TTP-aHUS secondary to autoimmune pancreatitis, alcohol abuse, gallstones, and granulomatous pancreatic inflammation due to sarcoid.

Our case is unique because TTP developed after the patient had developed PEP. The mechanism in TTP-induced pancreatitis is not well understood but is proposed to be pancreatic tissue damage occurring as a result of intracellular activation of enzymes leading to a secondary inflammatory response and release of cytokines (Citation1). In case of TTP occurring after pancreatitis, it is plausible that the widespread immunological response as a result of pancreatitis may be involved. Pancreatitis causes vascular injury and endothelial dysfunction that may expose the subendothelial matrix. Further, as a result of vascular insult, there is a deficiency of ADAMTS13. Both these processes activate platelets and cause thrombotic occlusion of microvasculature. This can explain the occurrence of TTP in our case.

Conclusion

No data has shown any direct correlation between pancreatitis and aHUS because most people can respond to PEX and are considered to have TTP. Looking at our case, there could be a real possibility of aHUS having an association with pancreatitis and should be kept in mind in future. To conclude, the association of pancreatitis is more appropriate to make with TMA and not just TTP or aHUS. In any case presenting with TMA, the first step should be PEX. On the failure of therapy for 3–5 days, eculizumab should be considered without any further delay because mortality in an aHUS increases with delay in its treatment.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from the organization or elsewhere to conduct and publish this study.

References

- Ali MA, Shaheen JS, Khan MA. Acute pancreatitis induced thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2014; 18: 107–9.

- Arimoto M, Komiyama Y, Okamae F, Ichibe A, Teranishi S, Tokunaga H, etal. A case of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura induced by acute pancreatitis. Int J Gen Med. 2012; 5: 307–11.

- Mori Y, Wada H, Gabazza EC, Minami N, Nobori T, Shiku H, etal. Predicting response to plasma exchange in patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura with measurement of vWF-cleaving protease activity. Transfusion. 2002; 42: 572–80.

- Sinha A, Gulati A, Saini S, Blanc C, Gupta A, Gurjar BS, etal. Prompt plasma exchanges and immunosuppressive treatment improves the outcomes of anti-factor H autoantibody-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome in children. Kidney Int. 2014; 85: 1151–60.

- Caprioli J, Noris M, Brioschi S, Pianetti G, Castelletti F, Bettinaglio P, etal. Genetics of HUS: The impact of MCP, CFH, and IF mutations on clinical presentation, response to treatment, and outcome. Blood. 2006; 108: 1267–79.

- Chahal P, Tarnasky PR, Petersen BT, Topazian MD, Levy MJ, Gostout CJ, etal. Short 5Fr vs long 3Fr pancreatic stents in patients at risk for post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009; 7: 834–9.

- Fan JH, Qian JB, Wang YM, Shi RH, Zhao CJ. Updated meta-analysis of pancreatic stent placement in preventing post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015; 21: 7577–83.

- Andrade-Davila VF, Chavez-Tostado M, Davalos-Cobian C, García-Correa J, Montaño-Loza A, Fuentes-Orozco C, etal. Rectal indomethacin versus placebo to reduce the incidence of pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: Results of a controlled clinical trial. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015; 15: 85.

- Hosler GA, Cusumano AM, Hutchins GM. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and hemolytic uremic syndrome are distinct pathologic entities. A review of 56 autopsy cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003; 127: 834–9.

- Fujimura Y, Matsumoto M. Registry of 919 patients with thrombotic microangiopathies across Japan: A database of Nara Medical University during 1998–2008. Intern Med (Tokyo, Japan). 2010; 49: 7–15.

- Swisher KK, Doan JT, Vesely SK, Kwaan HC, Kim B, Lämmle B, etal. Pancreatitis preceding acute episodes of the thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura-hemolytic uremic syndrome: Report of five patients with a systematic review of published reports. Haematologica. 2007; 92: 936–43.

- Bergmann IP, Kremer Hovinga JA, Lammle B, Peter HJ, Schiemann U. Acute pancreatitis and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Eur J Med Res. 2008; 13: 481–2.