Abstract

Background: There is evidence that the addition of current medical student interviewers (CMSI) to faculty interviewers (FI) is valuable to the medical school admissions process. This study provides objective data about the contribution of CMSI to the admissions process.

Method: Thirty-six applicants to a 4-year medical school program were interviewed by both CMSI and FI, and the evaluations completed by the two groups of interviewers were compared. Both FI and CMSI assessed each applicant's motivation, medical experiences, personality, communication skills, and interests outside of the medical field, and provided a numerical score for each applicant on an evaluation form. Both objective and subjective data were then extracted from the evaluation forms, and paired t-test and rank order tests were used for statistical analysis.

Results: When compared with FI, CMSI wrote two to three times more words on the applicants’ motivation, personality, communication skills, interests, and overall evaluation sections (p<0.001) and provided about 60% more examples on the motivation section (p=0.0011) and communication skills section (p=0.0035). In contrast, FI and CMSI provided similar numbers of negative examples in these and in the personality section and equivalent overall numerical evaluation scores.

Conclusions: These results indicate that when compared with FI, CMSI give equivalent overall evaluation scores to medical school candidates but provide additional potentially useful information particularly in the areas of motivation and communication skills to committees assigned the task of selecting students to be admitted to medical school.

Introduction

The selection of students for medical school admission is a competitive process that includes assessment of both cognitive and non-cognitive abilities Citation1Citation2. Cognitive measures, which include undergraduate grade-point average and medical college admissions test scores, may predict subsequent academic performance but do not necessarily correlate with clinical performance Citation1Citation3Citation4. In contrast, non-cognitive measures include personal qualities noted in letters of recommendation, personal statements, and the personal interview. The personal interview, often conducted by a medical school faculty interviewer (FI), is one of the primary methods of assessing non-cognitive qualities such as motivation, awareness of community, socio-medical issues, maturity, involvement in school and community activities, and leadership Citation5. In fact, the Association of American Medical Colleges has challenged Admissions Committees to look first to personal qualities of applicants, such as professionalism and communication skills, and leave consideration of grade point averages and exam scores until later in the decision-making process Citation5Citation6. Although Admissions Committees often rank the impact of personal interviews higher on the list of selection criteria than cognitive measures Citation7, reliable and valid measurement of non-cognitive abilities remains elusive Citation7Citation8Citation9. It has been suggested that personal interviews must be well-structured and balanced to achieve reliability and validity Citation2Citation10.

The potential value of current medical students’ input in the medical school admissions process has been addressed Citation1Citation11Citation12Citation13Citation14Citation15Citation16. Applicants shared more information with current medical student interviewers (CMSI) than with FI Citation1Citation4Citation11, leading to discussion of topics that would not have been discussed during a faculty interview Citation11. In addition, their temporal closeness to the medical school experience allows CMSI to evaluate how an applicant will fit in to their specific institution Citation12Citation13. In addition to aiding in admissions decisions, current medical students can help in recruitment since they can provide information about non-academic concerns, such as residential and social life to applicants Citation11.

Although logistically and financially more complex than a single interview session with an individual or panel, multiple interviews such as in the multiple mini-interview model in which an applicant has about eight brief, consecutive interviews, may have increased reliability and predictive power Citation15Citation16Citation17. While the multiple mini-interview model may be advantageous, to our knowledge, the advantage of utilizing just one additional full-length (30–60 min) interview, specifically with a CMSI, in addition to a full-length interview with the FI, has not been specifically addressed.

In this report, evaluations of medical school applicants by CMSI and standard evaluators, in this case FI, following full-length interviews were compared. The hypothesis was that CMSI would be more likely than FI to obtain personal, non-cognitive information about medical school applicants.

Method

Interviewer training

The University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey – New Jersey Medical School (UMDNJ–NJMS) conducted a Student Interview Program (August–October 2007). Twenty-two current medical students (MS II–MS IV) with good academic standing and leadership in the medical student community were chosen to participate. To reduce bias when evaluating applicants Citation14, training of CMSI was comparable to that of FI; both interviewer groups were given 1–2 h of instruction and information by the Associate Dean of Admissions (G. H.), the staff of the admissions office, and voting members of the Admissions Committee on Citation1 the general procedures of an interview, Citation2 the objectives of an interview, Citation3 the expectations of the Admissions Committee, and Citation4 student characteristics to comment on as listed by section headings on evaluation forms.

Evaluation forms

Both FI and CMSI evaluation forms included the following seven section headings with a space for narrative comments below each heading: Citation1 Motivation; Citation2 Experiences in socio/medical fields (hereinafter ‘Medical experiences’); Citation3 Personality, character, and social attributes (hereinafter ‘Personality’); Citation4 Communication skills; Citation5 Interests outside of the medical field (hereinafter ‘Interests’); Citation6 Interviewer's overall evaluation of applicant (hereinafter ‘Overall evaluation’); and Citation7 Overall Numerical Score [a subjective numerical rating of the applicant on a scale of 0 (lowest score) to 5 (highest score) in half-point increments]. Information obtained from these seven items was the source of data for this study.

While not included in data collection, both forms also included the following sections: ‘Explanations of pertinent inconsistencies,’ ‘How well you feel the applicant will succeed academically’ and, if re-applicant, ‘Give details on how the applicant has improved academic credentials.’ Only the FI evaluation form also included the following sections: Citation1 Family influence on decision to attend medical school; Citation2 Discuss qualities that indicate how the applicant will perform as a physician; Citation3 How well does the applicant understand delivery systems in health care including the need to treat the medically indigent? and Citation4 Outline any activities and work experiences since graduation if applicant has already graduated from college.

Subject files

The files of 36 applicants interviewed by both the CMSI and the FI were used to obtain data for this study. Applicants who received CMSI interviews were selected randomly out of the total pool of applicants interviewed by FI at UMDNJ–NJMS during this time period. Each CMSI interviewed one to three applicants, which was consistent with the number of interviews completed by each FI during this period. Both CMSI and FI had access to the applicant's file which included an American Medical College Application Service application and letters of recommendation. CMSI and FI were instructed to complete the one-on-one interview in 30–60 min and then submit a completed interview evaluation form within 72 h of the interview. These forms were placed into the applicant's file to be reviewed by the medical school Admissions Committee.

Data collection

UMDNJ–NJMS Institutional Review Board's approval (protocol number 0120080024) was obtained prior to conducting this study. Data for each applicant were abstracted from the six narrative sections and the overall numerical score (see ‘Evaluation forms’ above) of the CMSI and FI evaluation forms by the two student directors of the Student Interview Program (authors CG and NT). Objective data consisted of number of words written (all sections except Medical experiences), number of examples given (all sections except Overall evaluation), and, of examples, number of negative examples (Personality, Communication skills, and Motivation sections) as well as Overall Numerical Score. Subjective data consisted of a Numerical Motivation Score devised from the comments in the Motivation section of the evaluation. The Numerical Motivation Score ranged from 0 to 10 and was based on the interviewer's comments concerning the applicant's motivation; 0 represented the lowest and 10 the highest level of applicant motivation. To obtain this score, the data abstractors rated the strength of the interviewers’ comments, e.g., ‘I was extremely impressed by this applicant's motivation’ (score = 10) vs. ‘I was not impressed by this applicant's motivation’ (score = 0), and researchers practiced using the system together to ensure inter-rater reliability.

Since two individuals would be collecting the data, it was necessary to establish inter-rater reliability between the data collectors in their recording practices. Prior to recording the data, the data abstractors cooperatively developed a method of data abstraction, then practiced, discussed, and compared their respective technique for quantifying data. Consistency was achieved when the data abstractors had the same score for number of words, number of examples, number of negative examples, and Numerical Motivation Score for all sections over two to three consecutive evaluations. Only after consistency was reached during the practice series did the researchers begin collecting and recording data to be used in the study.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed by using ‘Stata’ statistical analysis software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Because CMSI and FI interviewed the same applicant, the paired-sample t-test and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used to identify significant differences between CMSI and FI evaluations Citation18. Paired-sample t-tests were used when data were normally distributed, and Wilcoxon signed-rank order tests were used when data were not normally distributed, e.g., when comparing number of negative examples used by CMSI and FI. All tests were two-sided and run at an α level of 0.05.

Results

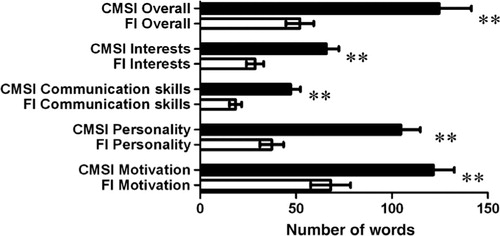

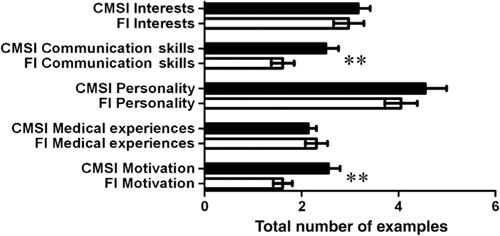

When compared with FI, CMSI wrote two to three times more words in the Motivation, Personality, Communication skills, Interests, and Overall evaluation sections (p<0.001) () and provided about 60% more examples when discussing applicants’ Communication skills (p=0.0035) and Motivation (p=0.0011) (). In contrast, CMSI and FI provided similar numbers of examples in the Interests, Personality, and Medical experiences sections. Additionally, there was no significant difference in the number of negative examples in the Motivation, Personality, or Communication skills sections, in Numerical Motivation Score (e.g., 6.5 for CMSI vs. 6.2 for FI), or in Overall Numerical Score (e.g., 4.2 for CMSI vs. 4.4 for FI).

Fig. 1. Number of words (±standard error) written by current medical student interviewers (CMSI) and faculty interviewers (FI) in Overall evaluation, Interests, Communication skills, Personality, and Motivation sections of the medical school admissions interview evaluation form. **Statistically significant difference. Overall p<0.001, Interests p<0.001, Communication skills p<0.001, Personality p<0.001, Motivation p=0.002.

Fig. 2. Number of examples (±standard error) written by current medical student interviewers (CMSI) and faculty interviewers (FI) in the Interests, Communication skills, Personality, Medical experiences, and Motivation sections of the medical school admissions interview evaluation form. **Statistically significant difference. Communication skills p=0.007, Motivation p=0.002. Other comparisons are not significant.

Discussion

These findings support the hypothesis that CMSI provide additional information about medical school applicants to that offered by FI. When compared with FI, CMSI consistently wrote more words about applicants’ Motivation, Interests, Communication skills, and Personality. In addition, CMSI provided more examples of Communication skills and Motivation than FI. The first finding could be explained by the fact that CMSI are less experienced in writing evaluations than FI and thus write more in an effort to avoid omitting necessary information. However, this was not always the case since FI used more examples in some sections than CMSI.

There are a number of possibilities for why CMSI provided more specific examples of Communication skills and Motivation than FI. First, it could be that CMSI are better able than FI to detect information in these specific areas. Also, applicants may share more information with CMSI than with FI. The latter explanation is likely because, as previous research Citation11 has shown, their closeness to the medical school experience and the interview process allows CMSI to provide a more relaxed interviewing atmosphere, a more thorough description of the student community and institutional academic style, and more candid answers to questions about residential and social life Citation12Citation13. In addition, CMSI may be more likely to emphasize the motivation and communication skills of an applicant because CMSI have personally experienced the learning environment of their institution and understand what qualities will help an applicant to succeed in and contribute to the school Citation12Citation13.

No differences between CMSI and FI were found in the number of examples in the Interests, Personality, or Medical experiences sections, in the number of negative examples in Motivation, Personality, and Communication skills sections, or in the Numerical Motivation Score or Overall Numerical Score. This concordance supports the findings of Nowacek et al. Citation19, and suggests that CMSI do not overvalue or undervalue the personal qualities of medical school applicants.

There are some limitations in this study. First, the background interviewing experience of the CMSI and FI differed; this was the first interviewing experience for most of the CMSI while many FIs had been interviewing for years. Also, the fact that the FI evaluation form had four more sections may have affected the quantity and quality of what was written in each section. Finally, information about the ultimate utility of the student interviews was not obtained, nor did this study assess whether members of the Admissions Committee valued and weighted CMSI evaluations differently from those of FI.

In conclusion, these findings indicate that when compared with FI, CMSI provide additional information about medical school applicants’ personal qualities, such as motivation and communication skills. While this information has the potential to help members of an Admissions Committee decide which students to admit to medical school Citation1Citation14, future research is needed to understand the ultimate utility of CMSI interviews.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry to conduct this study.

References

- Salvatori P. Reliability and validity of admissions tools used to select students for the health professions. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2001; 6: 159–75.

- Hughes P. Can we improve on how we select medical students?. J R Soc Med. 2002; 95: 18–22.

- Vancouver J, Reinhart M, Solomon D, Haf J. Testing for validity and bias in the use of GPA and the MCAT in the selection of medical school students. Acad Med. 1990; 65: 694–7.

- Eva K, Reiter H, Rosenfeld J, Norman G. The ability of the multiple mini-interview to predict preclerkship performance in medical school. Acad Med. 2004; 79: S40–2.

- Albanese M, Snow M, Skochelak S, Huggett K, Farrell P. Assessing personal qualities in medical school admissions. Acad Med. 2003; 78: 313–21.

- The AAMC. The AAMC project on the clinical education of medical students. Clinical skills education. WashingtonDC: AAMC, 2005.

- Kulatunga-Moruzi C, Norman G. Validity of admissions measures in predicting performance outcomes: the contribution of cognitive and non-cognitive dimensions. Teach Learn Med. 2002; 14: 34–42.

- Stansfield R, Kreiter C. Conditional reliability of admissions interview ratings: extreme ratings are the most informative. J Med Educ. 2007; 41: 32–8.

- Puryear J, Lewis L. Description of the interview process in selecting medical students for admission to U.S. medical schools. J Med Educ. 1981; 56: 881–5.

- Ann-Courneya C, Wright K, Frinton V, Mak E, Schulzer M, Pachev G. Medical student selection: choice of a semi-structured panel interview or an unstructured one-on-one interview. Med Teach. 2005; 6: 499–503.

- Gelmann E, Steward J. Faculty and students as admissions interviewers: results of a questionnaire given to applicants. J Med Educ. 1975; 50: 626–8.

- Koc T, Katona C, Rees P. Contribution of medical students to admission interviews. J Med Educ. 2008; 42: 315–21.

- Roby L. The medical student interviewer. J Med Educ. 2008; 42: 746–8.

- Edwards J, Johnson E, Molidor J. The interview in the admission process. Acad Med. 1990; 65: 167–77.

- Eva K, Reiter H, Rosenfeld J, Norman G. The relationship between interviewers’ characteristics and ratings assigned during a multiple mini-interview. Acad Med. 2004; 79: 602–9.

- Eva K, Rosenfeld J, Reiter H, Norman G. An admissions OSCE: the multiple mini-interview. J Med Educ. 2004; 38: 314–26.

- Rosenfeld J, Reiter H, Trinh K, Eva K. A cost efficiency comparison between the multiple mini-interview and traditional admissions interview. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2008; 13: 43–58.

- Christensen LB, Stoup CM. Introduction to statistics for the social and behavioral sciences. Thomson Brooks/Cole. Belmont CA, 1991

- Nowacek G, Bailey B, Sturgill B. Influence of the interview on the evaluation of applicants to medical school. Acad Med. 1996; 71: 1093–5.