Abstract

In 2002 the University of Michigan Medical School created a one-month course in advanced medical therapeutics (AMT). All senior medical students were required to complete the course. To provide some flexibility for students who were interviewing for residency positions the AMT course was created using a distance-learning model, and in the 2008–2009 academic year it was offered in a fully online format. The components of the course are weekly case-based modules, a weekly online seminar, quizzes based on modules and seminars, and a research project based on a therapeutic question. The paper discusses the development and components of the AMT course, a survey of fourth-year medical students who participated in the course between 2007 and 2010, and how the course evolved over three years.

In 2002, as part of a University of Michigan (UM) Medical School general curriculum revision, a committee of clinical faculty recommended the creation of a one-month course in advanced medical therapeutics (AMT) that would be required for all senior students. To give students some flexibility in scheduling to take the course, it was to be offered three times per year. The course would consist of lectures, small group sessions, and student presentations. Development challenges included finding faculty members who would be available and willing to participate in teaching the course, especially when it was to be repeated three times in short succession, and addressing student absenteeism due to residency interviews.

Faculty determined that developing the course using a distance-learning model would likely address these challenges. There is a large and growing body of research documenting the increasing popularity of distance-learning approaches to meet general and specific learning needs in the health sciences. These reports provide strong evidence that online learning is equally as effective Citation1Citation2Citation3 or in some cases more effective Citation4 compared to classroom learning. Findings related to learner preference are inconsistent. In some cases the surveyed population preferred classroom learning due to issues such as teacher-student interaction Citation1, but in other cases they preferred online learning due to the uniformity of the learning experience Citation5 and the flexibility and convenience of this approach Citation6Citation7. Although the research findings provide significant support for online learning as an effective pedagogical method, researchers warn that appropriate instructional design and easy-to-access technology are both key to effective outcomes Citation8Citation9. In fact, a positive by-product of distance learning is the acquisition of advanced computer-based skills Citation4Citation10Citation11.

A carefully designed and executed distance-learning approach proved to be a good fit for the AMT course. A set of online materials could be created and used repeatedly, with updates handled as needed, limiting the need for extensive and repeated faculty time and effort. Students could access course materials from anywhere via the internet, giving needed flexibility and resolving potential travel/attendance conflicts associated with residency interviews. Also, this approach provided opportunities for active, self-directed learning.

Development of the AMT Course

The content of the AMT course represents a collaborative effort among more than 30 faculty members in the UM Medical School's basic science and clinical departments, including pharmacology, surgery, internal medicine, emergency medicine, family practice, psychiatry, obstetrics/gynecology, and physical medicine and rehabilitation. Pedagogical and assessment approaches represent a collaborative effort between the course director, a highly regarded teacher and professor in infectious diseases, and faculty educators in the Office of Medical Education. Design and programming was a collaboration between the course director and multimedia design and development experts in the Medical School's learning resource center.

A prototype was reviewed by curriculum leaders with input from medical students and technologists. The final structure of the course consisted of four components.

A weekly series of case-based modules (e.g. cardiology).

Weekly seminars.

Weekly online open-book quizzes.

A student research project submitted online at the end of the course.

Technical Features

From a technical standpoint, the system employed basic HTML, CSS, and a small amount of JavaScript. This combination of technology has several advantages: the product can be hosted on the university's course management system (CMS); the course director can edit and create cases using Dreamweaver and other text or web editors; and the multimedia development team can program cases as needed. Hosting the course materials on the university's web server also has advantages, including pre-existing security and access control, familiarity of the medical students with the CMS and its features, and the ability for course developers to track utilization and evaluate the usefulness of course materials. Flash software is used for videos. This format is pre-installed on web browsers: it works on Macintosh and Windows operating systems, and on computers that have tight security restrictions such as those at the University of Michigan Health System. Quizzes were created and delivered to students via the Medical School's QuestionMark (Perception) quiz system. Finally, seminars were webcast over Adobe Connect, which could easily be accessed from laptop computers anywhere in the USA as students interviewed for residencies.

Course Content

Learning outcomes for the AMT course focus on advanced cognitive processes, including analysis, synthesis, and evaluation, that underlie clinical reasoning and complex decision-making. This contrasts with the rote memorization of facts that students are required to master in their pre-clinical years. Students are expected to peruse the reference material which the faculty provides, but they are also encouraged to seek other resources to answer questions and complete their projects. Outside resources can include internet searches, library holdings, and faculty consultation. It is hoped that students leave this course with a greater appreciation for self-education, especially as this relates to a critical reading of the published literature.

Case-Based Modules

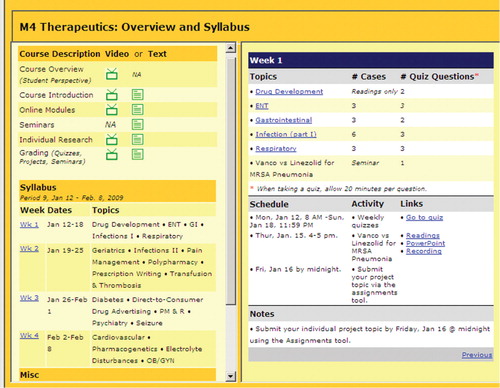

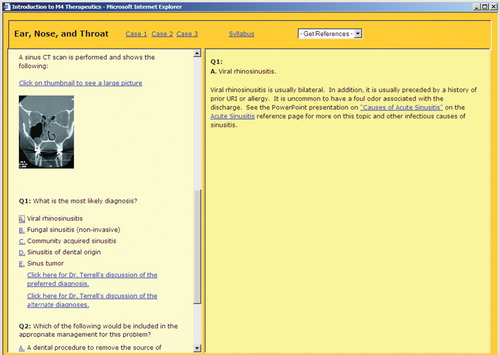

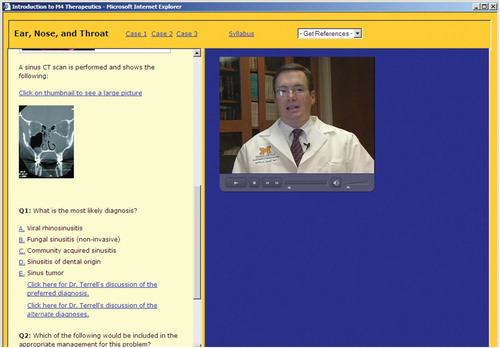

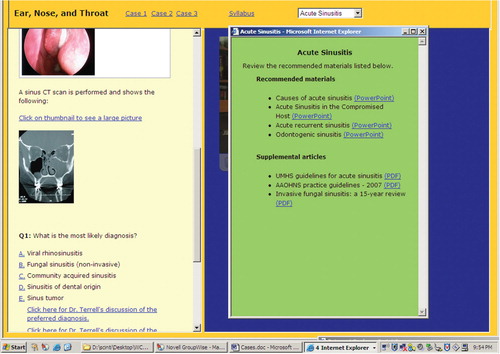

Online learning modules have been created for 20 topic areas, and each week students are responsible for reviewing four or five areas (). Topic areas were chosen to represent a broad range of therapeutic issues and we continue to add topics each year. More than 20 faculty members with expertise in each topic area have provided content and references. Content includes between three and 11 case scenarios per topic area. Each area contains figures, article links, and multiple-choice questions with explanations for each right and wrong answer (). In addition, one- to three-minute videotaped explanations by faculty members are provided for each multiple-choice question (). The video clips provide insight and feedback focused on the practice of medicine. References include recommended and supplemental material such as guidelines, articles, and PowerPoint slides (). Since the course was created, 270 references and PowerPoint presentations have been added to the program. Students can choose topic areas they would like to focus on; each area has a mandatory quiz associated with it (see below). Each year faculty contributors are asked to review their modules and reference material and make appropriate changes. If changes are extensive another videotape is created.

Weekly Seminars

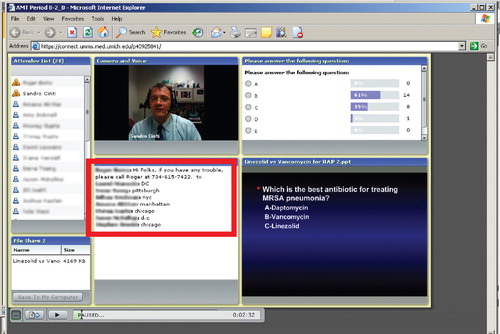

Each week students must participate in a one-hour seminar on a variety of topics, including both medical and surgical therapies and how these are reported and interpreted in academic journals. The first year the course was implemented (2006–2007) as a pilot, students were expected to be physically present at seminars, and each seminar was offered twice a week. The second year (2007–2008), because many students were interviewing during the course, seminars were broadcast online using Adobe Connect so traveling students could sign on to participate remotely. Starting in 2008–2009 seminars were presented completely online. Students are now required to sign on live for at least two of four seminar sessions. Seminars are recorded and can be viewed later by students who cannot be online at the time of the session. A participating student can see the speaker and the PowerPoint presentation and ask questions by texting. Although the speaker can view a list of participants, he/she cannot see students (). The seminars have been made more interactive by including a polling function that allows the speaker to ask students multiple-choice questions ( upper right).

Quizzes

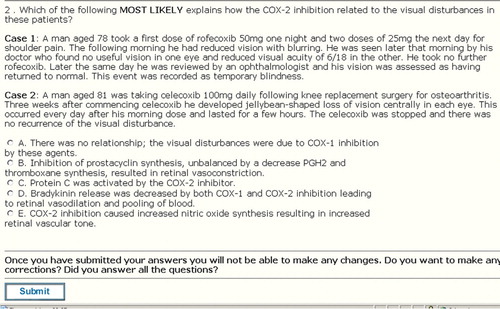

All AMT quizzes are online. Initially, quizzes were administered at the end of each week and included content on the weekly topics. Quizzes were in the form of case presentations, and students were given four hours to complete 10–12 questions. Quiz takers were allowed to use any resources other than fellow students or content experts to answer questions. During the pilot, quizzes were composed of both multiple-choice and short-answer questions; the short-answer questions were designed to explore students’ thought processes in problem solving, analysis, and synthesis. Because of the time that had to be devoted to reading the short answers, categorizing them, and providing feedback to 170 students, the format was changed to multiple-choice type questions that assessed higher-order thought processes. Since 2008–2009 each topic area and seminar has an associated quiz with between one and four questions. Students have 20 minutes per question and receive an immediate score and feedback upon submitting the quiz (). Multiple-choice answers are given point values between 0 and 10 and explanations are given for the final score (). Students can take each quiz at any time during the week.

Research Project

Each student in the AMT course is required to complete a research project and evaluate four other projects. During the first week of the course students must identify a therapeutic question that is of special interest to them and submit a proposal to the course director. The objective is for students to research a narrowly defined therapeutic topic using eight or more scholarly references, and then present the findings in a PowerPoint presentation, table, or document (Word). An example of an appropriate project is “Efficacy of Palivizumab on the Prevention of RSV in Children.” This award-winning project was narrowly defined and the student was able to focus on one or two seminal papers on the topic. Projects are turned in online at the end of the third week of the course and each student is placed into one of six groups based on their project category. During the fourth (and last) week of the course students must evaluate four projects in their designated group. The purpose of these evaluations is to push students to think critically about how therapeutic data are presented. Were the evaluated papers valid? Was the presenter convincing? How could the presentation have been improved? Finally, the course directors grade each project based on organization, depth of the literature review, and presentation of the material. Each year between three and six students receive a commendation for the best projects and up to three of these students present an online seminar on their project. A repository of previous projects, indexed based on category (e.g. neurology), is available for students to peruse.

Grading

Final AMT grades are based on quizzes (60%), projects (20%), and seminar attendance (20%). Students are able to drop one quiz question per week and must be present for two out of four seminars. They are able to view their quiz scores online at any time during the course.

Student Evaluation of the AMT Course

Survey Tool

At the end of each AMT four-week session, students are asked to complete an online course evaluation. The survey has 21 questions, including 14 Likert scale items and four questions that ask for comments. The Likert scale items have four different formats with five possible answers (). The mean score for each question is between 1 and 5. For example, the mean score in 2008–2009 for the question “Course learning outcomes were clear” was 3.87 (between neutral and agree). Questions requesting comments were:

If you answered “strongly disagree” or “disagree “to “The three components of the course (online material and resources, seminars, project) fit together well to assure learning,” please explain.

What worked well in this course?

What did not work well in this course?

How can this course be improved?

Table 1. Multiple-choice responses for three student cohorts

Survey data have been obtained for 2007–2008 (Cohort 1), 2008–2009 (Cohort 2), and 2009–2010 (Cohort 3) AMT student cohorts (n = 88, n = 82, n = 106, respectively). The only changes in the course that occurred between these three cohorts were a change in quiz structure (no more short answers; topic-focused quizzes) and seminar structure (completely online seminars) between Cohorts 1 and 2. The following is a summary of the data separated into quantitative and qualitative sections.

Quantitative

summarizes the results for Cohorts 1, 2, and 3 students. Students in all cohorts spent nine to 14 hours per week working on the AMT course. Most students agreed and tended toward strong agreement that the flexibility in the course assisted in scheduling interviews in their fourth year, the technology worked well, and the online material was easy to access. All three cohorts agreed that the course was appropriately challenging and stimulated thinking at a complex level (mean scores 3.80–4.14). The overall quality of the course was rated as good to very good for Cohort 1 (mean 3.73) and Cohort 2 (mean 3.72), and improved in Cohort 3 (3.96).

Qualitative

The major qualitative findings were that most students felt the flexibility of the course was a major asset, and many felt the time required was more than they expected. Regarding specific elements of the course, most respondents enjoyed the case-based modules and appreciated the reference material. However, several students commented that there was too much information to sift through in the modules and the reference section of each module could be cut significantly to include the one or two most important documents. In addition, several respondents felt that some PowerPoint presentations lacked sufficient detail to be stand-alone references.

Students generally enjoyed the online seminars but expressed some stress about having to be physically they have to be present for 2 of 4 sessions. Four or five students in each cohort felt seminars were not necessary at all and did not add value to the course.

Students expressed several concerns about the quiz structure. Several felt that quiz questions were too difficult and/or too “nit-picky” and “not… designed to test my knowledge from completing the case studies and reading.” Some respondents in all three cohorts mentioned a lack of correlation between case-based modules and quizzes. Others, while acknowledging that quiz questions were difficult, felt they were appropriately challenging at the M4 level.

Regarding research projects, several respondents felt these were a valuable learning experience and “a good exercise for practice of evidence-based medicine.” Major concerns about the research project included a lack of clear expectations for the project and lack of specific grading criteria. A few students suggested abolishing the project requirement altogether in order to decrease the workload and allow more time to review the case-based modules.

Changes in the AMT Course and Future Directions

Over the three years that the AMT course has been required at the UM Medical School, several changes have occurred. As mentioned, after 2007–2008 (Cohort 1) all seminars were offered online and students could sign on from anywhere in the USA. It was not unusual in Cohorts 2 and 3 to have six or seven students signing on from different cities (). Quizzes were changed from questions with short answers to multiple-choice questions with partial credit answers. Furthermore, quizzes were offered throughout the week and were associated with each case-based module. As a result of these changes, there were fewer concerns among Cohorts 2 and 3 students about time constraints in completing the quizzes. To make research projects more relevant and challenging, several students in Cohorts 2 and 3 were given commendations for outstanding projects, and six students were asked to present their projects as a seminar session in the fourth week of the final 2008–2009 and 2009–2010 AMT sessions.

Future changes are planned in all components of the AMT course. First, case-based modules will be updated and the reference section in each will be streamlined to include more focused, relevant and updated materials. Second, quiz questions will be reformulated to correspond to each case-based module. The questions will continue to challenge higher-level thinking of the students (e.g. analysis, synthesis, evaluation), but we will rewrite or drop questions perceived by students as requiring too much attention to detail. Third, seminars will be made more interactive by adding polling questions and possibly developing several point/counterpoint formats to generate discussion and highlight the gray areas of medical therapeutics. There have been discussions about using virtual-reality technology to allow participants to be present in a virtual auditorium. Fourth, research projects will continue but we will develop better guidelines for preparing and grading the projects. We will continue to recognize outstanding projects with commendations and offers for winners to present these projects as online seminars. Furthermore, we are developing a repository of all projects so students can peruse these in the future. Finally, the UM Medical School is in the early stages of developing a learning management system to assist students who wish to take more responsibility for their learning. The AMT course is currently piloting the system and results will be available within the next year.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank all the faculty who provided content for the AMT course, including cases, quiz questions, and video footage. We would also like to thank faculty who gave symposia. We would like to thank Dr Jeffrey Terrell for allowing us to use his image in the manuscript.

References

- Elison-Bowers P, Snelson C, Casa de Calvo M, Thompson H. Health sciences students and their learning environment: a comparison of perceptions of on-site, remote-site and traditional classroom students. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2008; 5: 2.

- Hawthorne K, Prout H, Kinnersley P, Houston H. Evaluation of different delivery modes of an interactive e-learning programme for teaching cultural diversity. Patient Educ Couns. 2009; 74: 5–11.

- Limpach AL, Bazrafshan P, Turner PD, Monaghan MS. Effectiveness of human anatomy education for pharmacy students via the internet. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008; 72: 145.

- Walsh K. Online educational tools to improve the knowledge of primary care professionals in infectious diseases. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2008; 21: 64.

- Jeun BS, Javan R, Gay SB, Olazagasti JM, Bassignani MJ. An inexpensive distance learning solution for delivering high-quality live broadcasts. Radiographics. 2008; 28: 1251–8.

- Ertmer PA, Nour AY. Teaching basic medical sciences at a distance: strategies for effective teaching and learning in internet-based courses. J Vet Med Educ. 2007; 34: 316–24.

- Larvin M. E-learning in surgical education and training. ANZ J Surg. 2009; 79: 133–7.

- Cook DA. Web-based learning: pros, cons and controversies. Clin Med. 2007; 7: 37–42.

- Cook DA, McDonald FS. E-learning: is there anything special about the “E”?. Perspect Biol Med. 2008; 51: 5–21.

- Glinkowski W, Ciszek B. WWW-based e-teaching of normal anatomy as an introduction to telemedicine and e-health. Telemed J E Health. 2007; 13: 535–44.

- King RV, Murphy-Cullen CL, Mayo HG, Marcee AK, Schneider GW. Use of computers and the internet by residents in U family medicine programs. Med Inform Internet Med. 2007; 32: 149–55.