Abstract

Success in academic medicine requires scientific and clinical aptitude and the ability to lead a team effectively. Although combined MD/PhD training programs invest considerably in the former, they often do not provide structured educational opportunities in leadership, especially as applied to investigative medicine. To fill a critical knowledge gap in physician-scientist training, the Vanderbilt Medical Scientist Training Program (MSTP) developed a biennial two-day workshop in investigative leadership. MSTP students worked in partnership with content experts to develop a case-based curriculum and deliver the material. In its initial three offerings in 2006, 2008, and 2010, the workshop was judged by MSTP student attendees to be highly effective. The Vanderbilt MSTP Leadership Workshop offers a blueprint for collaborative student-faculty interactions in curriculum design and a new educational modality for physician-scientist training.

Success in academic medicine depends on many factors, but a hallmark of accomplishment in this discipline that receives little attention in medical school curricula is aptitude in leadership and organizational behavior. In particular, physician-scientists must learn and apply advanced skills in recruitment, retention, communication, conflict resolution, providing feedback, and strategic planning, among other competencies. Most training programs offer exposure to these skills primarily through the passive observation of peers and mentors, who may be inconsistent or even ineffective role models.

Research in organizational behavior and business administration indicates that people making the transition from individual contributors to leaders find that the experience of ‘leading’ differs significantly from what was anticipated and is substantially more challenging. In an analysis of 19 first-year managers conducted in 2003, Hill Citation1 describes the process as a ‘transformation – a fundamental change in identity and point of view,’ often associated with stress and intense emotion. Furthermore, she notes that lack of preparation and support often results in failed leadership transitions. The quality of leadership also varies significantly across individual leaders, even in the same organization. Importantly, leadership quality predicts critical outcomes such as productivity and turnover Citation2.

Formal instruction in leadership and organizational behavior is an expressed need among those preparing for careers in academic medicine. Many self-help books for assistant professors incorporate descriptions of management principles and leadership competencies Citation3 Citation4 Citation5 Citation6 . The Sigma Xi Postdoctoral Training Survey identified structured training opportunities in leadership and teamwork (including communication and management) as main areas requiring improvement in postdoctoral training Citation7. The National Research Council of the National Academies cites training in areas such as laboratory management, business and budgeting, communication, and team leadership as a critical opportunity for improving the postdoctoral experience Citation8. The Howard Hughes Medical Institute along with the Burroughs Wellcome Fund led well-attended ‘boot-camp’ workshops in 2002 and 2005 on laboratory management and have published a detailed companion guide that dedicates two chapters to leadership and mentoring skills Citation9. The AAMC Citation10, Cell Citation11, and Science Careers Citation12 have highlighted leadership resources and workshops designed for postdoctoral fellows. Importantly, efforts in leadership training have documented value in the career development of medical school faculty. At the University of California at San Diego, assistant professors who complete a leadership curriculum are significantly more likely to be promoted on the tenure track Citation13.

There are limitations to currently available educational modalities in leadership for physician-scientist trainees. First, leadership programs tend to exist as supplements to traditional curricula, although integration of the content into formal training programs is frequently identified as a major opportunity for improvement Citation7 Citation8. Second, available modalities are in large part designed for trainees at the postdoctoral level and beyond. There are limited resources targeted to graduate students and medical students, who have more time to reflect on key concepts and develop core skills before it becomes necessary to apply them. Third, congestion in predoctoral graduate and medical school curricula, combined with an acknowledgment that not all graduate and medical students will pursue academic careers, leaves little time for formal leadership training experiences. Combined MD/PhD training programs, which seek to train leaders in academic medicine, are ideal settings for integrating leadership training into the formal predoctoral curriculum.

The Medical Scientist Training Program (MSTP) at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine provides integrated training in medicine and science leading to both MD and PhD degrees. Most Vanderbilt MSTP trainees complete the first two years of medical school, pursue graduate studies in a doctoral program for three to four years, and return to medical school to complete the final two years of clinical training. Core elements of the Vanderbilt MSTP developed specifically for dual-degree students include a literature-based seminar series, clinical preceptorship during research training, a data club, a career development workshop, a physician-scientist speaker series, and an annual retreat.

In 2005 we considered how our MSTP could better equip students to become effective leaders. The following describes our student-driven approach to answering this question, the leadership curriculum we implemented for our trainees, an evaluation of that curriculum, and the implications and remaining questions for further investigation. While leadership training for physician-scientists could be effective in many distinct forms, lessons learned from our experience utilizing a joint student-faculty committee to develop and execute an original curriculum may provide guidance to others seeking to meet this well-defined need.

Premises

The Vanderbilt MSTP leadership curriculum has two primary goals: to expose MSTP students to the importance of proficiency in leadership skills for success in academic medicine, and to provide instruction in a set of core competencies for both immediate and long-term practice. We began by considering how an optimal leadership curriculum for MSTP students would fit within the current MSTP educational framework. First, we were aware that MD/PhD programs exist in an environment with finite resources. Therefore, we sought to develop a quality, sustainable program on a limited budget. Second, constraints on faculty and student time demanded an efficient program. Third, accomplishment of our educational goals would require the most relevant sources of information, including academic research, expert consultants, and intra-institutional resources. We proposed that the following specific questions be addressed.

Content – What specific content should be included to address our learning objectives?

Teaching modalities – What instructional materials and learning activities would be most appropriate?

Format and delivery – What format should be adopted and how should the content be delivered?

Timing– At what point in the MSTP curriculum should students attend the leadership program?

Evaluation – How should the program be evaluated?

To address these questions, we assembled a committee that included six MSTP students representing a cross-section of experience levels within the MSTP, the MSTP director, and faculty members from the Owen School of Management and the Peabody College of Education and Human Development. The diverse perspectives among the committee members were essential in our endeavor to select and adapt instructional approaches to be maximally effective, interesting, and relevant to our target audience. Over time, the committee has rotated off graduating senior students and replaced them with rising junior students, providing fresh perspectives for the committee and new leadership opportunities for our trainees.

Content

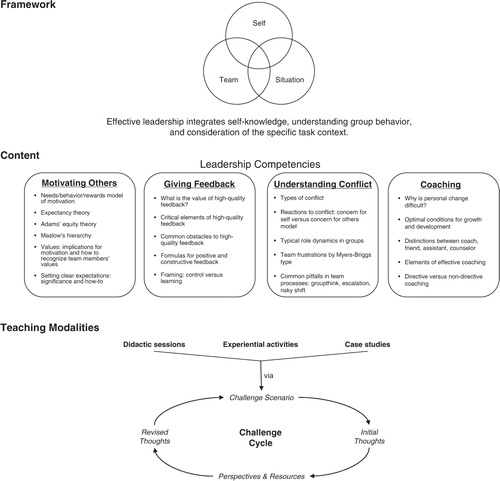

Training experiences providing content relevant to the actual work to be done are more likely to produce learning that is usable in practice Citation14 Citation15. Committee members specializing in education and management were well versed in generic leadership competencies and the standard frameworks commonly used to categorize current research and theory involving human behavior in organizations. However, these standard constructs of the leadership discipline were not always optimally relevant nor directly translatable to the specific nuances of investigative leadership in the setting of academic medicine. The committee therefore filtered the generic competencies using the experience of other committee members about the role of scientific and medical leaders to determine the most relevant competencies for MSTP students to learn. The four competencies featured in our curriculum are motivating others, giving effective feedback, understanding conflict, and coaching. These competencies were then adapted to a standard framework of organizational theory: the self, the team, and the situation. Questions that illustrate the conceptualization of leadership in this context include the following.

What do I need to know about myself as a leader, and what do I need to know about the individuals who form my team?

What do I need to know about team dynamics and team effectiveness?

What do I need to know about situational factors that influence individual and team performance?

Teaching modalities

We used a ‘challenge cycle’ approach to deliver the workshop content Citation16. In this approach, students are initially challenged to solve a problem with no prior teaching about how to do so. Students are encouraged to struggle through the problem using their pre-existing ideas, which are likely to be undeveloped and perhaps inaccurate. After students arrive at their best solution, formal instruction is provided about relevant concepts and theories. Equipped with this new knowledge, students then revise their thoughts about the original challenge. This cycle is repeated with new challenge scenarios, giving students the chance to revise their understanding of the central concepts further as they consider each related problem and apply their expanding knowledge base.

Instructional formats that actively involve the participants are more likely to allow information obtained in the classroom to be applied by participants in real-world situations Citation14 Citation15. Thus we planned the workshop to be as interactive as possible. Common methods of involving participants include experiential activities and discussion of cases, and we employed both of these modalities.

Experiential activities

A number of effective experiential activities specifically designed for use across disciplines currently exist within the wealth of educational tools for leadership and organizational behavior. Thus we were able to draw on previously developed activities rather than inventing our own. Student attendees participated in several of these group challenges to illustrate specific points about leadership and organizational behavior. These activities also provided students with new shared experiences, which served as valuable reference points throughout the rest of the workshop. In the discussion that followed each activity, we focused on how the experience illustrated the leadership competencies we had already covered in the workshop, including the importance of developing a shared language among a team to be able to complete a task; the typical roles that team members adopt and which are most effective; the diversity in the types of decision-making processes groups may adopt and which are most effective in which situations; and while ideally a group will outperform its top individual, why sometimes the opposite is true.

Case studies

The core of our workshop involved analysis of cases in investigative leadership. A synthesis of the literature on case-based instruction indicates that effective teaching cases should be relevant, realistic, engaging, challenging, and instructional Citation17. Although thousands of cases have been published for teaching leadership in business settings, these do not fit the distinctive context of a laboratory. Therefore we wrote nine original cases ( and Appendix for full text; Boxes 1 and 2 for two sample cases), each describing a different scenario where realistic but obviously ineffective leadership behaviors in the areas of motivation, providing feedback, conflict management, and coaching were exhibited by a principle investigator, attending physician, or team member. At each workshop, three of these cases were integrated into the curriculum. For each case, students in subgroups of five or six were asked first to discuss the scenario, considering the basis of the underlying problem, how it could have been avoided, and what should happen next. The whole group then reassembled for a broader discussion in which students were challenged to apply and further develop their working understanding of leadership in the context of relevant patterns of human behavior. In describing realistic, relatable problems that unmistakably arise from a lack of leadership skills, the cases also serve to highlight the importance of acquiring the core competencies covered in the workshop to be successful in academic medicine.

Table 1. Central themes from nine original cases developed to highlight key leadership concepts in the setting of academic medicine

Since much of the workshop content was new to MSTP students, we concluded that it would be appropriate to include didactic lectures with the other activities in our curriculum. Although formal lectures can be limited in fostering skill-building, personal insight, and problem-solving capability, they can be used effectively for disseminating information Citation18. During the didactic sessions, students were taught critical language and theory underlying each of the selected competencies. Our didactic sessions were highly interactive, discussion-based lessons. This format was achieved by illustrating concepts with realistic scenarios from academic medicine while challenging students to pinpoint the origin of a problem or describe the forces at work. Students often contributed examples from their own experiences that related to each topic and practiced applying new learned techniques via interactive exercises built into each lesson. An overview of the workshop, including a sample of specific content addressed under each leadership competency, is provided in .

Format and delivery

In reviewing the literature on leadership, Avolio, Walumba, and Weber Citation19 concluded that interventions designed to enhance participant leadership tended to have positive impact on ratings of leader performance even when the length of the intervention was as little as a day or less. Accordingly, we thought that a short, intensive experience would have a positive impact on students. We considered alternative formats (such as a seminar series) and concluded that a two-day workshop would be most appropriate given the time constraints imposed by the MSTP curriculum and our overall goal of generating deep, substantive thought and discussion about investigative leadership among the student attendees.

The management and education faculty members have more than 20 years of combined experience in teaching cases and facilitating experiential exercises. Therefore, the committee decided that they would facilitate the workshop. Student committee members remained actively engaged in the workshop presentation, serving as process observers and subgroup facilitators for experiential activities. Ultimately, inclusion of leadership content experts as workshop facilitators was invaluable in achieving our goal of active participation by student attendees. These faculty members were highly proficient in teaching the content and eliciting high-quality discussion among the group participants.

Timing

We concluded that students would benefit most from the workshop after having spent sufficient time in a laboratory to acquire some fluency in lab cultural norms and exposure to the unique challenges of the research team environment. Furthermore, we wanted to address the sharp contrast between the conventional hierarchical nature of training in clinical medicine and the highly variable and less-structured environments encountered by research teams, and the attendant requirements for different leadership competencies in each. Concurrently, we sought to reach students sufficiently early in their training to provide an immediate opportunity to practice new skills in the laboratory setting before returning to medical school. Therefore, we chose students in their first and second years of graduate training (third and fourth years in the program) as the target audience for our workshop. Additionally, students are encouraged to return to the workshop as senior students; returning participants benefit from revisiting and revising their concepts of leadership, while other workshop participants benefit from discussions enriched by the experiences of senior students.

Evaluation

Students completed evaluations at the close of each workshop to assess participant reaction to the program Citation20. Half of the evaluation consisted of Likert-scale questions, where students were asked to rate their agreement (1, strongly disagree; 5, strongly agree) on whether each portion of the workshop was, independently, ‘well organized and executed’ and ‘relevant to leadership concepts and skills.’ The second half of the evaluation consisted of free-response questions, including: What is the most valuable skill or concept that you gained from the workshop? Were there any topics or skills you wish the workshop had covered that were not included? Was the workshop well balanced in terms of presenting didactic information versus teaching practical skills? What are the one or two greatest strengths of the workshop? What are the one or two greatest opportunities for improvement?

Conclusions

We are able to draw several conclusions from the three workshops offered thus far (in 2006, 2008, and 2010). Data from our Likert-scale evaluation questions indicate that, overall, students agree that each component of the workshop was both well organized and executed as well as relevant to leadership; the mean of all scores in both categories combined was 3.8 in 2006, 4.3 in 2008, and 4.3 in 2010 (see ). The evaluations also indicate that the participants placed significant value on the interactive nature of the workshop. Each year an overwhelming majority of the responses to ‘Was the workshop well balanced in terms of presenting didactic information versus teaching practical skills?’ were affirmative, most with comments indicating that they were engaged by the interactive activities and appreciated the opportunity to apply the didactic lessons. Furthermore, most of the 2008 and 2010 responses to ‘What are the one or two greatest strengths of this workshop?’ related to the experiential learning activities and the interactive nature of the workshop and its facilitation of learning.

Table 2. Likert-scale evaluation responses following the Vanderbilt MSTP leadership workshops conducted in 2006, 2008, and 2010

Our success in engaging students in active learning was evident by observing students participating in the workshop. During didactic sessions, unplanned topics often arose as the discussion led to new questions and ideas, stimulating meaningful conversations that we had not anticipated. We pursued these topics while encouraging students to consider new issues in the context of the leadership competencies covered earlier in the workshop. Among these ‘extra-curricular’ discussions were: can a laboratory group be effectively divided into separate subteams? Is rewarding success by individual laboratory team members acceptable? What is the best way to do so?

There was not much consensus in the evaluations about opportunities for improvement. In 2008 the strongest theme that emerged was that while students appreciated the examples that were included to illustrate most concepts, some concepts still came across as abstract. To address this weakness for the 2010 workshop, we examined each of the main teaching points and added as many examples and illustrations as possible. Our 2010 evaluations suggest that this intervention was effective, as none of the 2010 participants thought that the concepts were too abstract, whereas ‘clarity of message’ was cited when students were asked to list the workshop's greatest strengths.

The 2010 participants indicated that the main weaknesses of the workshop were related to scheduling: inconvenient hours and too fast a pace to cover each topic in appropriate depth. To address these concerns for the next installment, we are considering narrowing the focus of the workshop to fewer topics that will allow each one to be addressed in more depth, leaving students with a short list of take-home points. Concordantly, we recognize the importance of emphasizing to students that our workshop should be considered an introduction to a vast and important field. First and foremost, we hope that our students leave the workshop with an appreciation of the necessity of acquiring leadership competencies to achieve success in investigative medicine, along with a solid understanding of a few basic concepts and the motivation to seek opportunities for future leadership development training.

We have also considered strategies to assess the long-term impact of the training obtained in the workshop on the subsequent careers of our students. While formal outcomes such as appointment to leadership positions (e.g., department chair or dean) cannot be measured for quite some time, there are several options for assessing more intermediate effects of the workshop on participants’ professional development. These include surveying former participants at designated intervals after completing the workshop (e.g., after one, three, and five years) for examples of specific occasions in which they have implemented an intervention based on a concept introduced in the workshop, along with a reflective analysis about why the intervention was or was not successful. This process could also provide an opportunity for former participants to contribute additional real-life case studies to the workshop curriculum and offer fresh insights into the application of leadership competencies as a form of peer consulting.

An alternative idea for assessing the effectiveness of the workshop is to generate a written exam to test the ability of participants to apply workshop competencies to a new set of case studies. This evaluation tool could be applied at various intervals after the workshop. However, since the goal is to provide leadership skills that students will continue to develop and apply long after the workshop is completed, we think that testing immediately after completion of the workshop may not be very meaningful.

Based on the feedback we collected during its three initial installments, we think the leadership workshop provides an effective introduction to investigative leadership for MSTP students. Our participants have helped us identify several keys to our success: involving students in curriculum design; using expert facilitators who are knowledgeable and engaging; placing emphasis on interactive learning; and employing real-world case scenarios to illustrate key concepts. We will continue to offer our workshop biennially and incorporate improvements based on student feedback. Following up with workshop participants as they progress through their careers will allow us to measure qualitative long-term outcomes and make appropriate changes to maximize the workshop's impact.

Declarations of interest

No conflict of interest exists for any of the authors of this manuscript. This project was supported by Public Health Service award T32 GM07347 for the Vanderbilt Medical Scientist Training Program.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jim Bills, Nancy Brown, Roger Chalkley, John Erickson, Michelle Grundy, Indriati Hood, Bonnie Miller, Emil Petrusa, Larry Swift, and Susan Wente for helpful suggestions and review of the manuscript.

References

- Hill L. Becoming a manager: how new managers master the challenges of leadership2nd edn. Harvard Business Press. Boston MA, 2003

- Buckingham M, Coffman C. First, break all the rules: what the world's greatest managers do differently. Simon & Schuster. New York, 1999

- Diamond R. Field guide to academic leadership. Jossey-Bass. San Francisco CA, 2002

- Wilson E, Perman J, Clawson D. Pearls for leaders in academic medicine. Springer Science+ Business Media. New York, 2008

- Cohen C, Cohen S. Lab dynamics: management skills for scientists. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. New York, 2005

- Sapienza A. Managing scientists: leadership strategies in scientific research2nd edn. Wiley-Liss. Hoboken NJ, 2004

- Davis G. Doctors without orders. American Scientist, 2005; 93.

- National Research Council of the National Academies. Bridges to independence: fostering the independence of new investigators in biomedical research. WashingtonDC: National Academies Press, 2005.

- Making the right moves: a practical guide to scientific management for postdocs and new faculty. 2nd edn. Chevy ChaseMD: Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Burroughs Wellcome Fund, 2006.

- Leadley J. Medical school based career and leadership development programs. WashingtonDC: Association of American Medical Colleges, 2006. [updated October 2010]. Available from: https://www.aamc.org/initiatives/leadership/ld/ [cited 7 July 2011].

- Aschwanden C. Managing to excel at science. Cell. 2008; 132: 911–13.

- Austin J. Special feature: laboratory management. Science Careers, 2007

- Ries A, et al.. Retention of junior faculty in academic medicine at the University of California, San Diego. Acad Med. 2009; 84: 37–41.

- Noe R. Employee training & development4th edn. McGraw-Hill. New York, 2008

- Rothwell W, Kazanas H. Mastering the instructional design process: a systematic approach4th edn. Pfeiffer. San Francisco CA, 2004

- National Research Council of the National Academies. How people learn: bridging research and practice. WashingtonDC: National Academies Press, 1999.

- Kim S, et al.. A conceptual framework for developing teaching cases: a review and synthesis of the literature across disciplines. Med Educ. 2006; 40: 867–76.

- Arthur W Jr, Bennett W Jr, Edens PS, Bell ST. Effectiveness of training in organizations: a meta-analysis of design and evaluation features. J Appl Psychol. 2003; 88: 234–45.

- Avolio BJ, Walumbwa FO, Weber TJ. Leadership: current theories, research, and future directions. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009; 60: 421–49.

- Phillips J. Handbook of training evaluation and measurement methods3rd edn. Gulf Publishing. Houston TX, 1997

Appendix A: Appendix

Box 1. Sample case study – ‘Oil and water’

Dr Cornet, an energetic assistant professor, is studying a new signaling pathway that leads to apoptosis of tumor cells following treatment with resveratrol. She was recently awarded her first R01 grant to extend her preliminary results. It was clear early on that her regimented work style clashed with that of Thomas, a postdoctoral fellow she recruited to work on the resveratrol project. He is talented at the bench and was very productive as a graduate student, but works erratic hours and has been known to sleep in the lab overnight while his assays are running.

While he focused primarily on the R01-funded project, he also started a handful of side projects, explaining to Sarah (a graduate student in the lab) that ‘pursuing tangents was how I landed my Science paper in grad school, and it's the only way to make interesting discoveries.’ He was most excited about findings from one project that suggested new mechanisms by which resveratrol shrinks polyps in a mouse model of colon cancer.

Though he spent months repeating the experiments Dr Cornet cited in her grant application, Thomas was unable to reproduce her preliminary findings. Eventually he met with her and declared, ‘There is something seriously flawed with your preliminary data. I don't see the resveratrol effect.’ Dr Cornet noticed a key positive control was missing, so she asked him to repeat the experiment again. She also suggested he ‘arrive earlier to lab. You aren't in grad school anymore.’

This angered Thomas, as he had chosen a career in science so he could work his own hours. Besides, he had many projects going and was generating data from all of them. He went back to Dr Cornet's pathway, and this time after including all of the controls he was able to replicate the earlier data. However, the more he learned about the signaling intermediaries, the more he became convinced that there was nothing novel about this pathway. Meanwhile, his side project uncovered an extremely interesting finding: not only did resveratrol induce apoptosis of colon cancer cells via an intrinsic pathway, but it also rescued MHC expression, allowing for efficient killing by cytotoxic T lymphocytes.

As months went by, Thomas and Dr Cornet's relationship became increasingly strained. Finally, Thomas barged into her office and slammed a notebook on her desk. ‘There is absolutely nothing novel about your pathway. I have checked it again and again and we are chasing nothing! I think my time should be spent on a more interesting project, like my colon cancer work,’ he said. Dr Cornet was not pleased to see her carefully orchestrated research plan and well-oiled approach scoffed at. She responded, ‘I recruited you for one reason and one reason only: to work on this pathway. You need to stop wasting your time with the mice and get back to the project you were hired to do!’

After Thomas stormed out, Dr Cornet picked up the phone and dialed her closest colleague. ‘Pat, my postdoc is driving me crazy. He has been working on my new R01, and his experimental results just don't make sense in terms of our preliminary studies. His data seem solid, but he omits controls because he is too interested in pursuing side projects. Pat, he just doesn't listen, what am I going to do?’

Meanwhile, Thomas found Sarah for lunch. ‘Dr Cornet is a moron. I have spent the last six months showing repeatedly that there is nothing novel about her hypothesis, and I think the underlying assumptions are flat wrong. But every time I meet with her, she tells me to do more experiments. I have never seen such clear negative results. But Dr Cornet refuses to listen. I have way more interesting data in our mouse model, and this work could lead to a publication in Science or Nature. What do you think I should do?’

Discussion questions

What is the conflict between Thomas and Dr Cornet?

What common ground do Thomas and Dr Cornet share?

How would you describe Dr Cornet's leadership style? How would you manage Thomas if he were your employee?

If you were Sarah, what would you tell Thomas; and if you were Pat, what would you tell Dr Cornet?

Should Dr Cornet change the way she runs her lab?

How should Dr Cornet and Thomas work to resolve the conflict?

How might this scenario be different if Thomas was a graduate student in Dr Cornet's lab?

Box 2. Sample case study – ‘A call to arms’

Dr Ferrell is an established investigator who has spent 20 years studying S. cerevisiae proteases, specifically how they cleave their substrates and what regulates their activity. His lab team has been productive and he has secured consistent and ample NIH funding. He knows that his research is unlikely to be immediately applicable to human disease, but Dr Ferrell loves science for the thrill of discovery and the opportunity to train students and fellows.

Dr Ferrell has recently become intrigued with the biodefense literature. With a PhD in microbiology, he knows about the organisms implicated in possible acts of bioterrorism. He was amazed to learn that although much is known about how microorganisms cause cellular injury, very little progress had been made in the development of new therapies. Upon learning that peptidase activity contributes to the toxicity of botulinum neurotoxin, Dr Ferrell began to wonder whether S. cerevisiae could be used to identify new therapeutic targets.

Dr Ferrell is excited about this possible new line of research. He hypothesizes that cellular injury caused by botulinum neurotoxin can be prevented by a drug that targets the essential toxin peptidase. The research would make extensive use of his yeast model, and would provide Dr Ferrell an exciting change in research philosophy, providing a clear end goal: to characterize a drug target and identify a new intervention strategy.

Dr Ferrell is currently in the last year of his major R01 grant, which he has held continuously for 15 years. He has never had problems renewing grants, but with reductions in NIH funding he was more anxious about the upcoming competing-renewal application than others in the past. He notes that despite budget cutbacks, biodefense research is being well funded. Although he thinks his new ideas about botulinum neurotoxin have substantial merit, this is a field with which he is relatively unfamiliar. He is concerned that his first attempt at submitting a biodefense grant application may be unsuccessful.

At a recent lab meeting, Dr Ferrell proposed the change in research direction, and was disheartened to hear that many lab members had strong reservations.

Jamie is a research assistant who has mastered yeast culture and cloning techniques, and her concern is that the new project will employ more cell- and animal-based techniques with which she is completely unfamiliar. She worries that she will be replaced.

Mark is a second-year graduate student who is currently writing his thesis proposal and generating data to support his specific aims. While he is excited about the biodefense idea, he has concerns that his past year of work in the lab would be rendered worthless. Furthermore, he is a month away from getting married and does not want the onerous task of reading lots of biodefense papers before being able to make an informed decision about changing his project.

Praveet is six months into his postdoctoral fellowship. He applied for an F32 grant, but the application did not receive a fundable score. Although he is eager to participate in the new project, he is concerned about funding needed to support his position.

Barbara, the lab manager, thinks that Dr Ferrell knows what is best for the lab and that the hesitation to embrace fully the change in research directions by the other lab members is unfounded. ‘Biodefense, here we come!’ she shouted at the end of their meeting.

Dr Ferrell returned to his office bewildered by the resistance he was facing from his lab team in embracing this new change in direction. He had been convinced that it would invigorate the lab and benefit everyone. Now he is not so sure, and he lies awake at night wondering if he will be able to obtain funding or have to retire early.

Discussion questions

What is the best way to make a change in strategic direction?

How can Dr Ferrell enhance his likelihood of getting his biodefense grant funded?

Should Dr Ferrell even submit an application for renewal of his R01 grant?

How should Dr Ferrell ensure that the change in research direction does not negatively impact any of the existing lab members? Should alleviation of their concerns be a goal?

How might Dr Ferrell have better approached his lab about this topic?

Should Dr Ferrell change the research direction of his lab?