Abstract

Aging is associated with reduced ability to maintain normal glucose homeostasis. It has been suggested that an age-associated increase in chronic pro-inflammatory state could drive this reduction in glucoregulatory function. Thioredoxins (Trx) are oxido-reductase enzymes that play an important role in the regulation of oxidative stress and inflammation. In this study, we tested whether overexpression of Trx1 in mice [Tg(TRX1)+/0] could protect from glucose metabolism dysfunction caused by high fat diet feeding. Body weight and fat mass gains with high fat feeding were similar in Tg(TRX1)+/0 and wild-type mice; however, high fat diet induced glucose intolerance was reduced in Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice relative to wild-type mice. In addition, expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α was reduced in adipose tissue of Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice compared to wild-type mice. These findings suggest that activation of thioredoxins may be a potential therapeutic target for maintenance of glucose metabolism with obesity or aging.

Aging is a significant factor in the progressive decline in homeostatic regulation of glucose metabolism Citation1. The primary dysfunction that causes this decline is the development of peripheral insulin resistance Citation1. Several factors, including increased fat accumulation, decreased lean mass and elevated circulating fatty acids, can contribute to this phenotype. However, aging alone has been shown to have distinct effects on insulin response in skeletal muscle and other tissues independent of these other factors Citation1–Citation4. Diminished sensitivity to insulin is the greatest risk factor for the development of metabolic diseases like Type 2 diabetes mellitus, the most common metabolic defect in the elderly Citation5.

The direct cause of the decline in glucose regulation with age is not clear but recent findings have suggested that an important factor may be chronic inflammation. In humans and rodents, the circulating and tissue levels of several pro-inflammatory cytokines increase with age Citation6 Citation7. Chronic inflammation has also been proposed to be a significant cause of several age-associated diseases including diabetes Citation8. For more than a century, it has been known that anti-inflammatory treatments can reduce some effects of diabetes and insulin resistance Citation9. More recently, the molecular mechanisms linking inflammation with insulin resistance have been clarified using cell culture and mouse models. For example, the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor α) causes insulin resistance in cell cultures; conversely, mice lacking TNF-α or its receptors are protected from insulin resistance induced by obesity or high fat diet Citation10 Citation11. Similarly, the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6 (Interleukin-6) also reduces insulin signaling and glucose utilization in cell culture Citation12. These cytokines are thought to cause insulin resistance by activating stress-signaling pathways like the JNK (c-Jun N-terminal kinases) pathway Citation13. In support of this, ablation of JNK in mice prevents obesity-induced insulin resistance Citation14.

Thioredoxins (Trx) are important oxido-reductase enzymes that function as antioxidants, as redox-regulating enzymes, and as anti-inflammatories. In an NADPH-dependent reaction, disulfide bonds in multiple substrate proteins can by reduced by Trx with subsequent reduction of oxidized Trx by thioredoxin reductases. There are two primary forms of thioredoxins: thioredoxin 1 (Trx1) which is localized to the cellular cytosol and thioredoxin 2 (Trx2) which is localized to the mitochondria Citation15. Trx itself does have some chemokine-like attributes Citation16, but the anti-inflammatory effects of Trx1 are thought to be mostly due to its antioxidant actions. Mice that over-express Trx1 show reduced inflammation, immune cell infiltration, oxidative damage and cellular apoptosis when exposed to pro-inflammatory stimuli like cigarette smoke or diesel exhaust particles Citation17 Citation18. Trx1 also plays a significant role in the reduction of inflammation in murine myocarditis and colitis models and in response to lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation Citation19–Citation21. Trx1 may additionally regulate the effects of inflammation by modulating downstream stress-signaling pathways. Reduced Trx1 binds to and inhibits the activity of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) Citation15. Activated ASK1 promotes the stress-responsive JNK pathway, among others; thus, Trx1 indirectly controls JNK signaling Citation22.

Because Trx1 plays a central role in the regulation of inflammation, it might be predicted that over-expression of Trx1 can slow aging or age-related diseases. Previous studies have shown that the median lifespan of mice over-expressing human Trx1 [Tg(TRX1)+/0] is greater than wild-type mice Citation23 Citation24. Further, Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice showed a significant reduction in the total incidence of acidophilic macrophage pneumonia as a probable cause of death Citation24. In this study, we tested whether over-expression of Trx1 could prevent defects in glucose metabolism. Because laboratory mice under normal husbandry conditions do not generally develop diabetes-like phenotypes even with age, we used a dietary intervention to induce glucose intolerance and chronic inflammation. High fat diet feeding and obesity in mice have been clearly shown to stimulate a pro-inflammatory state, particularly in the growing adipose tissue Citation25. In this study, we used high fat feeding to test whether Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice were protected from diet-induced obesity. In addition, we tested whether Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice were protected from the pro-inflammatory state previously shown to be associated with increased fat accumulation.

Methods

Animals and feeding studies

Expression of Trx1 in the strain of Tg(TRX1)+/0 used in previous studies was shown to decline with age Citation24. Because these changes in Trx1 over-expression could add a significant confound to data collected using these mice, we generated additional lines of Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice that use the endogenous TRX1 promoter to regulate expression. These mice were generated using a fragment of the human genome containing the TRX1 gene [a BAC clone (RP11-427L11) from Children's Hospital Oakland Research Institute's (CHORI) BACPAC Resources Center (BPRC), Oakland, CA.] and 8.3 and 12.3 kb of the 5′- and 3′-flanking sequences, respectively. Mice were genotyped using PCR primer pairs designed to screen for the presence of the hTRX1 gene in mice (primer pairs to the 5′ untranslated region, exon 1 and a sequence within exon 5). We have confirmed transmission, stable integration, and successful passing to progeny of the TRX1 transgene in three founder lines. The first line of transgenic mice were used in this study; prior to this study, these mice had been successfully backcrossed into the C57BL/6J background for >7 generations (The Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor ME). Further details on the line of mice will be presented in an additional manuscript (in preparation).

Male Tg(TRX1)+/0 and littermate wild-type control mice were maintained on standard NIH-31 chow from weaning at a density of 2–4 mice per barrier cage in a specific pathogen free facility. When mice reached 4.5–6 months of age, cages were randomly assigned to be fed either of two defined diets (Purina Test Diets, Richmond IN): low fat (10% kCal from lard, Purina Test Diet 58Y2) or high fat (45% kCal from lard, Purina Test Diet 58V8). The energy composition of each diet in terms of kCal/gram food is: 18.3% protein:10.2% fat: 71.5% carbohydrate for low fat 58Y2 and 18.3% protein:45.2% fat:36.5% carbohydrate for 58V8. In both cases, the primary source of protein was casein, the primary source of fat was lard and the primary sources of carbohydrates were sucrose, dextrin and maltodextrin.

Body weight was measured prior to feeding studies and biweekly during study. Food consumption per cage was monitored over 2-week periods. At the end of 16 weeks of feeding, fat mass and lean mass were measured by quantitative magnetic resonance (QMR) imaging (Echo QMR, Houston TX). At sacrifice, mice were euthanized by CO2 with cervical dislocation and tissues were dissected, weighed and stored at –80°C until analysis. For tissue composition, frozen tissues were brought to 4°C on ice and analyzed by QMR. Percentage of fat was calculated by the formula [fat mass/(fat mass + lean mass)]. All procedures involving the mice were approved by the Subcommittee for Animal Studies at the Audie L. Murphy Veterans Administration Hospital at San Antonio and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

Glucose tolerance tests and insulin measurements

After 8 weeks of feeding either diet, glucose metabolism was measured by glucose tolerance tests. Mice were fasted for 6 hours beginning at 9:00 AM and fasting blood glucose was determined by One Touch hand-held glucometer (LifeScan Inc., Milpitas CA). Mice were then given intra-peritoneal injection of glucose (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis MO) in 0.7% saline at a dose of 1.5 mg glucose/kg body weight. Blood glucose was measured at given intervals over 2 hours. Insulin levels were measured by ELISA (CrystalChem, Downers Grove IL) in whole blood collected from mice after 6-hours fast. HOMA-IR measurements were determined by the formula HOMA-IR=[fasting glucose (mg/dL)×fasting insulin (mU/L)]/405.

Measurement of gene expression by RT-PCR

Total RNA from 50 to 100 mg adipose tissue was prepared using Tri-Reagent (Sigma) treated with DNase I (Life Technologies, Grand Island NY). cDNA was produced using Retroscript for RT-PCR (Life Technologies). Real-time PCR was performed in Applied Biosystems 7900 Real-Time PCR system (Life Technologies, with default PCR program using primers for TNF-α, IL-6, Actin-γ, and Microglubin-β designed using ABI Primer Express software 3.1. Actin-γ and Microglubin-β were used as housekeeping reference genes. Samples were placed in 384-well real time PCR plate using a final volume of 10ul. Optimum reaction condition were obtained with 16.26 µl SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Life Technologies), 160 nM forward primer, 160 nM reverse primer, and 8 ng template cDNA in each well. Data analysis was performed using an absolute quantification standard curve method.

Statistics

Data for weight gain were measured by 2-Way Repeated Measures ANOVA with ‘diet’ and ‘genotype’ as variables. Data for tissue weight and body composition were analyzed by 2-Way ANOVA with post-hoc analysis by Holm-Sidak when applicable. Gene expression were analyzed by Student's t-test to determine the difference between genotype. Similarly, data for glucose tolerance tests were analyzed by Student's t-test for differences between genotypes in blood glucose values at each time point indicated. Method used to determine Area Under Curve for glucose tolerance tests was the Trapezoid Rule; these data were analyzed for genotype difference by Student's t-test. All data were analyzed using SigmaStat (Aspire Software, Ashburn VA).

Results

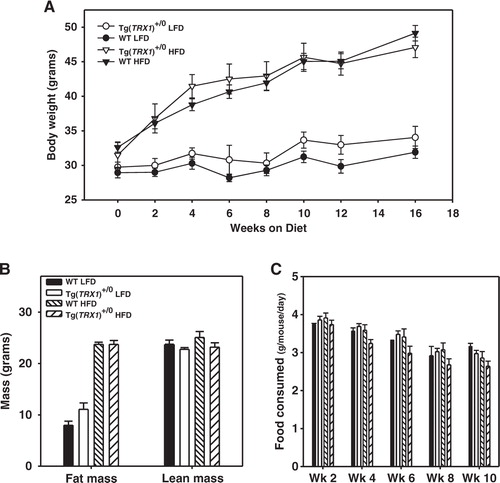

It was previously reported that the body weight of Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice maintained on standard mouse chow diet does not differ from wild-type mice, nor is there a difference between mice in food consumption Citation24. In this study, we fed young adult (4.5–6 months) male Tg(TRX1)+/0 and wild-type mice defined diets containing either 10% total kCal from fat (low fat) or 45% total kCal from fat (high fat) and tested whether over-expression of Trx1 could protect mice from obesity and/or defects in glucose metabolism. Through the 16 weeks on these diets, mice fed a high fat diet gained significantly more weight in this study than did mice fed a low fat diet (A; Variable ‘diet’: F=53.4, p<0.001). However, over-expression of Trx1 had no significant effect on weight gain in mice fed either low fat or high fat diet (A; variable ‘diet’ X ‘genotype’ interaction: F=2.5, p=0.358). We then assayed body composition of mice on both diets by QMR; as expected, mice fed a high fat diet had significantly more fat mass than mice fed a low fat diet (variable ‘diet’: F=321.1, p<0.001), but again we found no significant difference between Tg(TRX1)+/0 and wild-type mice in fat mass on either diet (B; variable ‘diet’ X ‘genotype’ interaction: F=3.8, p=0.062). High fat feeding had no effect on overall lean mass (variable ‘diet’: F=0.7, p=0.416) and over-expression of Trx1 also had no effect on lean mass of mice on either diet (B; variable ‘diet’ X ‘genotype’ interaction: F=0.192, p=0.665). Throughout the course of the experiment, Tg(TRX1)+/0 and wild-type mice did not differ in their food consumption on either diet (C).

Fig. 1. A. Body weight of wild-type (WT) and Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice fed either low fat (10% kCal) or high fat (45% kCal) over the course of this experiment. B. Fat mass and lean mass for WT and Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice after low fat and high fat feeding. C. Average food consumption over 2 week periods for WT and Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice fed low fat and high fat diets. For A, symbols represent average weight (±SEM) for indicated group at each time point. For B and C, bars represent the average (±SEM) of 5–9 mice within that group.

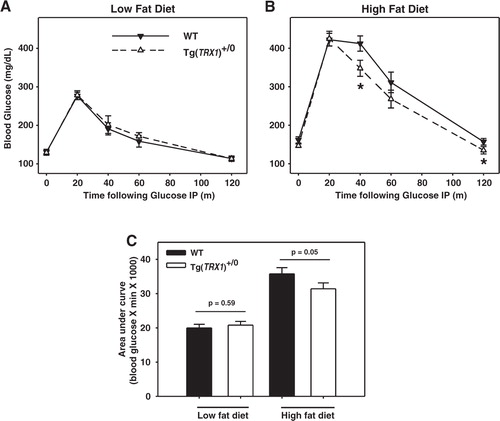

We next tested whether over-expression of Trx1 protected mice from defects in glucose metabolism associated with high fat diet and obesity. Glucose tolerance tests were performed after 8 weeks of feeding each diet. In mice fed the low fat diet, we found no difference between Tg(TRX1)+/0 and wild-type mice in these tests (A). As expected, we found that wild-type mice fed the high fat diet were significantly glucose intolerant relative to wild-type mice fed low fat diet (A,B). Surprisingly, high fat-fed Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice showed a significant improvement in glucose tolerance relative to high fat-fed wild-type mice (B). That is, Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice became less glucose intolerant when fed a high fat diet than did wild-type mice, suggesting over-expression of Trx1 prevents obesity-induced glucose dysfunction. These differences remained significant when glucose tolerance tests were analyzed by Area Under the Curve (C). While fasting blood glucose and insulin levels significantly increased with high fat feeding, these measures did not differ between Tg(TRX1)+/0 and wild-type mice on either diet (). We used these data points to calculate HOMA-IR, a measurement of whole animal insulin sensitivity. As a group, mice fed high fat diet had significantly increased HOMA-IR suggesting insulin resistance; however, we found no significant difference between wild-type and Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice fed either diet ().

Fig. 2. A. Glucose tolerance tests for mice fed low fat diet. B. Glucose tolerance tests for mice fed high fat diet. For both A and B, average values (±SEM) at each time point are given for WT (closed triangles) and Tg(TRX1)+/0 (open triangles) for 5–9 mice per group. Asterisks represent difference between genotype at indicated point reached p<0.05 by Student t-test. C. Area under curve (calculated by trapezoid method) for WT and Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice fed low fat or high fat diet. Bars represent average value (±SEM) for 5–9 mice in each group. Given p-values are for Student t-tests between groups indicated with horizontal line.

Table 1. Mean Tissue parameters (± SEM) of wild-type (WT) and Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice in this study

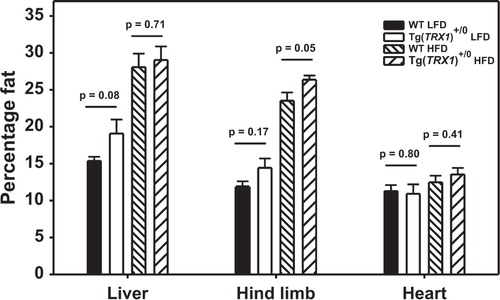

The regulation of glucose homeostasis in mice is regulated largely by the skeletal muscle and adipose tissue. Others have shown that defects in glucose metabolism with obesity can be caused by overall fat accumulation, increased accumulation of visceral adipose tissue relative to subcutaneous adipose tissue, and by ectopic fat accumulation in tissues like skeletal muscle Citation26 Citation27. High fat-fed Tg(TRX1) +/0 mice showed no reduction in overall fat accumulation (B), so we next measured whether over-expression of Trx1 altered fat distribution among the adipose tissue depots (i.e. away from visceral adipose and towards subcutaneous adipose). The weights of all adipose depots in high fat fed mice were significantly greater than the weights of adipose depots from low fat diet fed mice when analyzed by 2-Way ANOVA (). However, the mass of depots in Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice did not differ from those of wild-type mice on either diet (variable ‘diet’ X ‘genotype’ interaction: p>0.25 for each adipose depot). Furthermore, the weights of organs made up of primarily lean mass (i.e. heart, liver, kidney, and brain) also did not differ between Tg(TRX1)+/0 and wild-type mice (). To test for differences in ectopic lipid accumulation, we quantified the fat content of heart, liver, and hind-limb skeletal muscles by QMR. High fat feeding caused a significant increase in the fat content of liver and skeletal muscle (and a trend for an increase in heart), but there was no suggestion that Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice had reduced fat content in these tissues (). In fact, the hind-limb muscles of high fat-fed Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice had significantly elevated fat content compared to wild-type mice.

Fig. 3. Average fat content of tissues from WT and Tg(TRX1)+/0 fed low fat or high fat diets. Bars represent average value (±SEM) for 5–9 mice in each group. Given p-values are for Student t-tests between groups indicated with horizontal line.

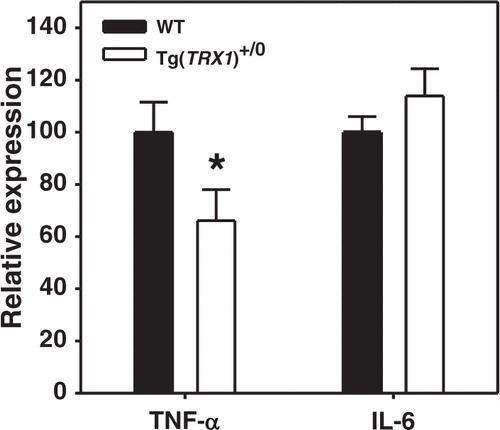

We next addressed whether the induction of inflammation by high fat feeding was prevented in tissues of Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice. Preventing pro-inflammatory cytokine production has previously been shown to prevent high fat diet induced insulin resistance Citation11 Citation14. Pro-inflammatory cytokine production by intra-abdominal adipose tissue depots has been shown to be increased in obesity Citation28. Perez et al. previously showed that Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice tended to have reduced activation of JNK signaling and reduction of IL-1β (though not TNF-α) in the liver of young mice on normal chow Citation24. Because peri-renal adipose depots were available after sacrifice, we used these as representative of intra-abdominal adipose depots. In this depot, we found in high fat animals that TNF-α mRNA expression was significantly lower in Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice relative to wild-type mice (). However, we found no significant difference in IL-6 expression in peri-renal adipose suggesting that the protection of glucose homeostasis in Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice may be TNF-α dependent.

Fig. 4. Relative mRNA expression of TNF-α and IL-6 in peri-renal adipose tissue from high fat-fed WT and Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice. Bars represent average expression value (±SEM) of samples from 5–8 mice in each group for each cytokine. Asterisk represents difference between genotype for indicated cytokine reached p<0.05 by Student t-test.

Discussion

In this study, we show that over-expression of Trx1 prevents glucose intolerance caused by high fat feeding without affecting fat accumulation or distribution. Interestingly, Miyamoto et al. found that diabetes and glucose intolerance in humans were associated with elevated levels of plasma thioredoxin Citation29. Kakisaka et al. also found that plasma thioredoxin levels were significantly higher in patients with Type 2 diabetes than in control patients Citation30. Because hyperglycemia is associated with increased oxidative stress, a compensatory antioxidant response might be the reason for elevated thioredoxin with glucose metabolism dysfunction Citation31. While expression of thioredoxin is elevated with diabetes, it has been shown that the activity of thioredoxin is actually reduced with hyperglycemia both in vivo and in cell culture Citation32 Citation33. This reduction in thioredoxin activity has been shown to be caused by hyperglycemia-induced expression of thioredoxin-interacting protein (TxnIP), a negative regulator of thioredoxin activity Citation32 Citation33. It is possible that Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice express Trx1 at levels high enough to counter this inhibitory action of hyperglycemia and thus minimize oxidative stress with high fat feeding. It is also possible that the human Trx1 (∼93% sequence identity to mouse Trx1) expressed in Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice is not recognized by mouse TxnIP, thereby maintaining high levels of activity with hyperglycemia.

Obesity is correlated with a significant increase in oxidative stress and damage in several tissues including skeletal muscle and adipose Citation34 Citation35. Others have shown that transgenic mice that over-express antioxidants like Mn superoxide dismutase (Sod2) or peroxiredoxin 3 are protected from insulin resistance caused by high fat feeding Citation36 Citation37. Similarly, over-expression of catalase specifically to the mitochondria (MCAT) can prevent defects in glucose homeostasis caused by either high fat feeding or by old age Citation38 Citation39. Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice are resistant to agents that generate oxidative stress by redox-cycling, like diquat and paraquat Citation23 Citation24. Furthermore, Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice have lower lipid and protein oxidation levels than wild-type mice both under normal husbandry conditions and in response to diquat Citation24. Thus, one explanation for the maintenance of glucose homeostasis in high fat-fed Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice could be by reduction of oxidative stress associated with obesity.

Thioredoxins are also anti-inflammatory and our data suggest that over-expression of Trx1 prevents obesity-induced glucose intolerance in part through this action. It has been thought that increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-6 may be the primary cause of insulin resistance with obesity and high fat feeding Citation10–Citation12. Thioredoxin has been shown to inhibit the production of these cytokines through regulation of nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) Citation40 Citation41. Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice fed a normal chow diet have been shown to have no change in TNF-α expression in the liver Citation24. We show here that expression of TNF-α is significantly reduced in peri-renal adipose tissue of high fat-fed Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice. This discrepancy might simply be due to characteristics inherent to these different tissues. It must be mentioned that mRNA expression of these pro-inflammatory cytokines may not directly correlate with their protein levels. Alternatively, it may be that pro-inflammatory stimuli are relatively low under normal dietary conditions and, thus, the activity of Trx1 on TNF-α (and other cytokines) is limited. Conversely, chronic stress like high fat feeding may stimulate pro-inflammatory expression to a greater extent at which time the protective effect of Trx1 is much more apparent. This might also suggest that the effects of Trx1 over-expression on lifespan may be much more dramatic if conducted under chronic stress such as that which occurs with obesity Citation24 Citation42.

Previous studies have suggested that Trx1 may have several roles in the prevention of metabolic diseases. For example, mice with targeted over-expression of Trx1 exclusively in pancreatic β-cells can prevent both autoimmune-induced and streptozotocin-induced diabetes Citation43. In both cases, the prevention of diabetes could be explained by protection of the β-cells and preservation of insulin secretion. Similarly, Hamada et al. found that mice that over-express Trx1 ubiquitously show protection from DNA oxidation caused by streptozotocin treatment Citation44. Yamamoto et al. showed that over-expression of Trx1 in the diabetic db/db mouse could reduce the progression of hyperglycemia and reduce plasma insulin levels Citation45. These previous studies all suggest that Trx1 may prevent diabetes by maintaining β-cell survival and preserving insulin secretion. We add to these previous findings by showing that Trx1 may also help to preserve peripheral glucose metabolism with high fat feeding. Together, these data suggest that thioredoxins may be an attractive target in treatment of Type 2 diabetes which is characterized by both peripheral insulin resistance and reduced pancreatic insulin production Citation46.

While this study shows that Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice are protected from high fat diet-induced glucose intolerance, we don't yet know whether age-induced declines in glucose metabolism are prevented in these mice. Work in humans and rodents has suggested that chronic inflammation with age may be a primary cause of many age-related diseases, including insulin resistance and diabetes Citation8. Lee et al. found that over-expression of catalase targeted to the mitochondria (MCAT) in mice prevented insulin resistance associated with aging Citation38. The median lifespan of Tg(TRX1)+/0 mice has been shown to be greater than that of wild-type mice Citation24; thus, it will be of great interest to determine whether the extended lifespan of these mice is also associated with the delayed occurrence of age-related pathologies such as reduced glucose homeostasis.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIA training grant T32 AG021890-05 for the study of the basic biology of aging (to A.B.S.) and Award Number 1 I01BX001023 from the Biomedical Laboratory Research & Development Service of the Veteran's Affairs Office of Research and Development (to Y.I.). Measurement of cytokine RT-PCR was performed by the Nathan Shock Center Oxidative stress and mitochondrial function core facility at UTHSCSA.

References

- DeFronzo RA. Glucose intolerance and aging. 1981; 4: 493-501. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Karakelides H, Irving BA, Short KR, O'Brien P, Nair KS. Age, obesity, and sex effects on insulin sensitivity and skeletal muscle mitochondrial function. 2010; 59: 89-97. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Jackson RA, Hawa MI, Roshania RD, Sim BM, DiSilvio L, Jaspan JB Influence of aging on hepatic and peripheral glucose metabolism in humans. 1988; 37: 119-29. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Gabriely I, Ma XH, Yang XM, Atzmon G, Rajala MW, Berg AH et al. Removal of visceral fat prevents insulin resistance and glucose intolerance of aging: an adipokine-mediated process?. 2002; 51: 2951-8. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Gambert SR, Pinkstaff S. Emerging epidemic: diabetes in older adults: demography, economic impact, and pathophysiology. 2006; 19: 221-8. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Bruunsgaard H. The clinical impact of systemic low-level inflammation in elderly populations. With special reference to cardiovascular disease, dementia and mortality. 2006; 53: 285-309.

- Kim HJ, Jung KJ, Yu BP, Cho CG, Choi JS, Chung HY Modulation of redox-sensitive transcription factors by calorie restriction during aging. 2002; 123: 1589-95. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Chung HY, Cesari M, Anton S, Marzetti E, Giovannini S, Seo AY et al. Molecular inflammation: underpinnings of aging and age-related diseases. 2009; 8: 18-30. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Shoelson SE, Lee J, Goldfine AB. Inflammation and insulin resistance. 2006; 116: 1793-801. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Hotamisligil GS, Peraldi P, Budavari A, Ellis R, White MF, Spiegelman BM IRS-1-mediated inhibition of insulin receptor tyrosine kinase activity in TNF-α- and obesity-induced insulin resistance. 1996; 271: 665-70. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Uysal KT, Wiesbrock SM, Marino MW, Hotamisligil GS. Protection from obesity-induced insulin resistance in mice lacking TNFalpha function. 1997; 389: 610-4. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Rotter V, Nagaev I, Smith U. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) induces insulin resistance in 3T3-L1 adipocytes and is, like IL-8 and tumor necrosis factor-α, overexpressed in human fat cells from insulin-resistant subjects. 2003; 278: 45777-84. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Nguyen MTA, Satoh H, Favelyukis S, Babendure JL, Imamura T, Sbodio JI et al. JNK and tumor necrosis factor-α mediate free fatty acid-induced insulin resistance in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. 2005; 280: 35361-71. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Hirosumi J, Tuncman G, Chang L, Gorgun CZ, Uysal KT, Maeda K et al. A central role for JNK in obesity and insulin resistance. 2002; 420: 333-6. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Powis G, Montfort WR. Properties and biological activities of thioredoxins. 2001; 30: 421-55. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Bertini R, Zack Howard OM, Dong H-F, Oppenheim JJ, Bizzarri C, Sergi R et al. Thioredoxin, a redox enzyme released in infection and inflammation, is a unique chemoattractant for neutrophils, monocytes, and T cells. 1999; 189: 1783-9. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Sato A, Hoshino Y, Hara T, Muro S, Nakamura H, Mishima M et al. Thioredoxin-1 ameliorates cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation and emphysema in mice. 2008; 325: 380-8. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Kaimul Ahsan M, Nakamura H, Tanito M, Yamada K, Utsumi H, Yodoi J Thioredoxin-1 suppresses lung injury and apoptosis induced by diesel exhaust particles (DEP) by scavenging reactive oxygen species and by inhibiting DEP-induced downregulation of Akt. 2005; 39: 1549-59. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Nakamura H, Herzenberg LA, Bai J, Araya S, Kondo N, Nishinaka Y et al. Circulating thioredoxin suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced neutrophil chemotaxis. 2001; 98: 15143-8. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Tamaki H, Nakamura H, Nishio A, Nakase H, Ueno S, Uza N et al. Human thioredoxin-1 ameliorates experimental murine colitis in association with suppressed macrophage inhibitory factor production. 2006; 131: 1110-21. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Liu W, Nakamura H, Shioji K, Tanito M, Oka S, Ahsan MK et al. Thioredoxin-1 ameliorates myosin-induced autoimmune myocarditis by suppressing chemokine expressions and leukocyte chemotaxis in mice. 2004; 110: 1276-83. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Tobiume K, Saitoh M, Ichijo H. Activation of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 by the stress-induced activating phosphorylation of pre-formed oligomer. 2002; 191: 95-104. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Mitsui A, Hamuro J, Nakamura H, Kondo N, Hirabayashi Y, Ishizaki-Koizumi S et al. Overexpression of human thioredoxin in transgenic mice controls oxidative stress and life span. 2002; 4: 693-6. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Perez VI, Cortez LA, Lew CM, Rodriguez M, Webb CR, Van Remmen H, et al. Thioredoxin 1 overexpression extends mainly the earlier part of life span in mice. . 2011; 66: 1286–99.10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, Tan G, Yang D, Chou CJ et al. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. 2003; 112: 1821-30.

- Coon PJ, Rogus EM, Drinkwater D, Muller DC, Goldberg AP. Role of body fat distribution in the decline in insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance with age. 1992; 75: 1125-32. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Gastaldelli A, Miyazaki Y, Pettiti M, Matsuda M, Mahankali S, Santini E et al. Metabolic effects of visceral fat accumulation in type 2 diabetes. 2002; 87: 5098-103. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AJ Jr Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. 2003; 112: 1796-808.

- Miyamoto S, Kawano H, Hokamaki J, Soejima H, Kojima S, Kudoh T et al. Increased plasma levels of thioredoxin in patients with glucose intolerance. 2005; 44: 1127-32. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Kakisaka Y, Nakashima T, Sumida Y, Yoh T, Nakamura H, Yodoi J et al. Elevation of serum thioredoxin levels in patients with type 2 diabetes. 2002; 34: 160-4. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Ceriello A. New insights on oxidative stress and diabetic complications may lead to a ‘Causal’ antioxidant therapy. 2003; 26: 1589-96. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Schulze PC, Yoshioka J, Takahashi T, He Z, King GL, Lee RT Hyperglycemia promotes oxidative stress through inhibition of thioredoxin function by thioredoxin-interacting protein. 2004; 279: 30369-74. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Turturro F, Friday E, Welbourne T. Hyperglycemia regulates thioredoxin-ROS activity through induction of thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) in metastatic breast cancer-derived cells MDA-MB-231. 2007; 7: 9610.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Furukawa S, Fujita T, Shimabukuro M, Iwaki M, Yamada Y, Nakajima Y et al. Increased oxidative stress in obesity and its impact on metabolic syndrome. 2004; 114: 1752-61.

- Grimsrud PA, Picklo MJ, Griffin TJ, Bernlohr DA. Carbonylation of adipose proteins in obesity and insulin resistance. 2007; 6: 624-37. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Hoehn KL, Salmon AB, Hohnen-Behrens C, Turner N, Hoy AJ, Mahgzal GJ et al. Insulin resistance is a cellular antioxidant defense mechanism. 2009; 106: 17787-92. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Chen L, Na R, Gu M, Salmon AB, Liu Y, Liang H et al. Reduction of mitochondrial H2O2 by overexpressing peroxiredoxin 3 improves glucose tolerance in mice. 2008; 7: 866-78. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Lee HY, Choi CS, Birkenfeld AL, Alves TC, Jornayvaz FR, Jurczak MJ et al. Targeted expression of catalase to mitochondria prevents age-associated reductions in mitochondrial function and insulin resistance. 2010; 12: 668-74. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Anderson EJ, Lustig ME, Boyle KE, Woodlief TL, Kane DA, Lin CT et al. Mitochondrial H2O2 emission and cellular redox state link excess fat intake to insulin resistance in both rodents and humans. 2009; 119: 573-81. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Ohashi S, Nishio A, Nakamura H, Kido M, Ueno S, Uza N et al. Protective roles of redox-active protein thioredoxin-1 for severe acute pancreatitis. 2006; 290: G772-81. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Takeuchi J, Hirota K, Itoh T, Shinkura R, Kitada K, Yodoi J et al. Thioredoxin inhibits tumor necrosis factor- or interleukin-1-induced NF-κB activation at a level upstream of NF-κB-inducing kinase. 2000; 2: 83-92. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Salmon AB, Richardson A, Perez VI. Update on the oxidative stress theory of aging: does oxidative stress play a role in aging or healthy aging?. 2010; 48: 642-55. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Hotta M, Tashiro F, Ikegami H, Niwa H, Ogihara T, Yodoi J et al. Pancreatic beta cell-specific expression of thioredoxin, an antioxidative and antiapoptotic protein, prevents autoimmune and streptozotocin-induced diabetes. 1998; 188: 1445-51. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Hamada Y, Fujii H, Kitazawa R, Yodoi J, Kitazawa S, Fukagawa M Thioredoxin-1 overexpression in transgenic mice attenuates streptozotocin-induced diabetic osteopenia: a novel role of oxidative stress and therapeutic implications. 2009; 44: 936-41. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- Yamamoto M, Yamato E, Toyoda S, Tashiro F, Ikegami H, Yodoi J et al. Transgenic expression of antioxidant protein thioredoxin in pancreatic beta cells prevents progression of type 2 diabetes mellitus. 2008; 10: 43-9. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.

- DeFronzo RA, Bonadonna RC, Ferrannini E. Pathogenesis of NIDDM. A balanced overview. 1992; 15: 318-68. 10.3402/pba.v2i0.17101.