Abstract

Antarctica is a highly interesting region for ecologists because of its extreme climatic conditions and the uniqueness of its species. In this article, we describe the trends in Antarctic ecological research participation by Latin American countries. In a survey of articles indexed by the ISI Web of Science, we searched under the categories “Ecology,” “Biodiversity Conservation” and “Evolutionary Biology” and found a total of 254 research articles published by Latin American countries. We classified these articles according to the country of affiliation, kingdom of the study species, level of biological organization and environment. Our main finding is that there is a steady increase in the relative contribution of Latin American countries to Antarctic ecological research. Within each category, we found that marine studies are more common than terrestrial studies. Between the different kingdoms, most studies focus on animals and most studies use a community approach. The leading countries in terms of productivity were Argentina, Chile and Brazil, with Argentina showing the highest rate of increase.

Antarctica has long been an interesting region for ecologists because of its extreme climatic conditions and its high level of endemism, among other reasons (Turner et al. Citation2009; Vyverman et al. Citation2010). The harsh environmental conditions of Antarctica include extremely low temperatures, high irradiance, desiccating winds, high salinity and very low liquid water availability (Robinson et al. Citation2003; Turner et al. Citation2009). In spite of these stressful conditions, often at the limit of what organisms can tolerate, Antarctic ecosystems are home to a number of species capable of surviving—and even thriving—in such extreme environments. Antarctic organisms are quite unique, many of them being endemic (Vyverman et al. Citation2010). This pronounced level of endemism is partly the result of Antarctica's high degree of isolation from other continents (Clarke et al. Citation2005; Barnes et al. Citation2006). Because of the Polar Front, this isolation not only encompasses terrestrial species but also marine species (Clarke et al. Citation2005; Olguin & Alder Citation2011).

A huge step in Antarctic science was made thanks to the International Geophysical Year (IGY), which triggered 18 months of scientific research in Antarctica in 1957–58. The IGY was followed by the Antarctic Treaty, which was signed in 1959 and ratified in 1961 (Gould Citation1965). With regard to Latin American countries, Argentina and Chile are the only original signatories of the Antarctic Treaty. Argentina and Chile were the first Latin American countries building permanent year-round stations in Antarctica and have, nowadays, several facilities in Antarctica (COMNAP Citation2011).

Antarctica is one of the few places where scientific research is a key factor in both politics and management not only because it determines the public policy agendas (Berkman et al. Citation2011) but also because the degree of research involvement is a criterion for eligibility of countries to be consultative parties in the Antarctic Treaty System (Auburn Citation1979; Pannatier Citation1994; Dudeney & Walton Citation2012). Of the countries that originally signed the treaty, the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia are the leaders in Antarctic research, followed by Germany, which signed almost 20 years later (East Germany was first in 1974 followed by West Germany in 1979), as shown by analyses of scientific publication output (Dastidar & Persson Citation2005; Dastidar Citation2007; Aksnes & Hessen Citation2009).

Our aim of this study was to identify the trends regarding Antarctic ecological research in Latin American countries by tallying peer-reviewed articles in international journals. In a survey of bibliographic material spanning 100 years (1911–2010), we used the number of articles published as an indicator of countries’ involvement in ecological research in the Antarctic. Specifically, the objectives of this article are to show Latin American participation in Antarctic ecological research, characterize it in terms of study subjects, approaches and study environments, and compare the tendencies among the leading Latin American countries.

Methods

Articles reporting ecological research in Antarctica were found using the ISI Web of Science. We restricted our article search to the ISI Web of Science because of the ease of access to this online database, the versatility of searches it permits and the assumed quality filter for articles. We are aware that many articles in small, more local journals published in Spanish or Portuguese are not being taken into account in our analyses, and that they could include valuable information. However, we do not believe that excluding these publications from our analysis would cause a bias in the survey: there is no reason to think that excluding these publications favours particular countries, taxonomic groups, levels of ecological organization or natural environments. We did seek ecological articles from sources not indexed by the ISI Web of Science, but found only some very early Antarctic ecological articles—probably among the first such articles—published by Chile and Argentina.

In the ISI Web of Science search, the timespan was constrained to the period 1911–2010 and search terms for the “Topic” were “Antarctica OR Antartica OR Antartida OR Antarctic.” The results were then further refined to the following “Web of Science Categories”: “Ecology,” “Biodiversity Conservation” and “Evolutionary Biology.” These three categories reflect: (i) the main focus of this study (Ecology); (ii) a topic of concern in Antarctic management (Biodiversity Conservation); and (iii) an area of increasing interest related to adaptation to current global changes affecting Antarctica (Evolutionary Biology). Limiting the search criteria to these three subject categories may have excluded some relevant articles. However, we have no reason to believe that restricting the search to these three highly appropriate subject categories would create any bias in our results.

For the purposes of this study, the Antarctic was defined in accordance with the Antarctic Treaty, that is, the region south of 60°S latitude. The application of this definition excluded articles on sub-Antarctic ecosystems that had been yielded by the search.

For the remaining articles, we recorded the country affiliations of each article. In our analysis and discussion, we focus on the articles where at least one of the authors was affiliated to an institution from a Latin American country, which we considered a metric of Latin American countries’ participation in Antarctic research. The presence of authors or co-authors from non-Latin American countries was also recorded for each of the articles to get an estimate of international collaboration.

We first calculated, for each year, the percentage of articles with at least one author who had a Latin American affiliation. All articles with a Latin American affiliation were then classified according to the country of affiliation, kingdom of the study species (Prokaryota, Protista, Fungi, Plantae, Animalia), level of biological organization (organism, population, community, ecosystem) and environment (terrestrial, marine). Subcategories (e.g. terrestrial or marine) to which articles belong were not mutually exclusive. We compared the subcategories across the total number of articles and their rate of increase. Because of the exponential increase shown by some groups, the rate of increase was calculated as the geometric mean and its standard deviation (SD; Gotelli & Ellison Citation2004). For the environment, we depicted it by country, showing the proportion of marine and terrestrial studies for each country, and we divided the data into two periods (1985–1999 and 2000–10) to get an estimate of changes over time. Third, we compared the most productive Latin American countries in terms of the total number of articles and the rate of increase (expressed as the geometric mean).

Results

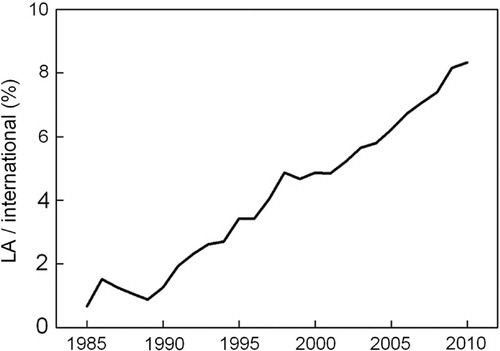

The search for peer-reviewed, international journal articles concerning Antarctica by Latin American authors yielded a total of 254 articles published between 1985 and 2010. No articles with Latin American authorship were found published before 1985. Of the articles found, 59% did not involve collaboration with non-Latin American countries and 41% were done in collaboration. Collaboration with non-Latin American countries has increased with the years, with more than half of the collaborative articles being published in the last five years of our analysis (2006–10). Such articles mainly involved Germany (39%), the United States (24%), Spain (14%) and France (7%). The ratio of articles with at least partial Latin American authorship to articles generated by all countries has been continuously increasing with time, reaching a maximum of 8.3% of the total in 2010 ().

Fig. 1 The ratio, expressed as percentages, between the total number of articles concerning ecology in Antarctica (international) and the number with at least partial Latin American authorship (LA).

We found Chile to be the first Latin American country to publish an ecological article in an ISI-indexed journal in 1985. It was a description of a new sea urchin species with ecological and evolutionary remarks (Larrain Citation1985). This does not imply that Antarctic science in Latin America started in the 1980s. The first articles that we were able to find published by Chilean authors in non-ISI journals date back to the late 1940s (Llaña Citation1948; Beddings Citation1949), when Chilean biologist Guillermo Mann published a book on Antarctic biology (Mann Citation1948). We found other early articles by Chilean researchers, mostly published in Spanish-language newsletters (e.g. Stuardo & Solis Citation1963; Schlatter et al. Citation1968; Moyano Citation1969; Hermosilla Citation1970). The first Argentinean publications that we were able to locate were a short note on a springtail (Hack Citation1949) and a general article on Antarctic biology (Mac Donagh Citation1951), both in Spanish.

Argentina, Chile and Brazil accounted for 95% of all articles yielded by the Web of Science search (). The remaining 5% was distributed among seven countries (grouped as “Others” below): Costa Rica, El Salvador, Mexico, Peru, Dominican Republic, Uruguay and Venezuela (). Authors from Argentina were involved in more than half of all articles with Latin American authorship.

Table 1 Antarctic ecological articles with authors with Latin American affiliations, sorted by country, and the percentage of the total for each country. Articles comprise ISI-indexed articles published between 1911 and 2010.

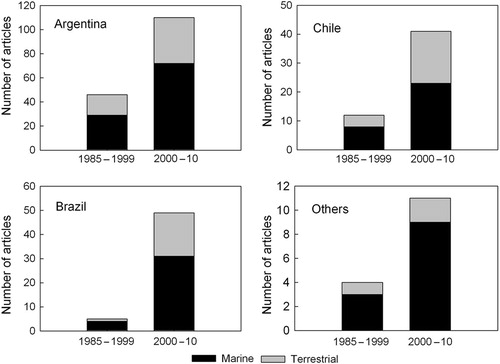

Marine environments were the setting for 64% of the articles, while 36% concerned terrestrial environments. This imbalance was found across the different countries, with marine studies fluctuating from 58% in Chile to 80% in the category of “Others” (). Between the two time periods used in the analysis (1985–1999 and 2000–10), a slight increase in terrestrial studies is also noted ().

Fig. 2 Articles with Latin American authorship concerning ecology in Antarctica, broken down by environment, country and time period. See for the list of countries grouped under “Others.” As some articles concerned include species that inhabit both marine and terrestrial environments, or more than one country was involved in the article, these categories are not mutually exclusive.

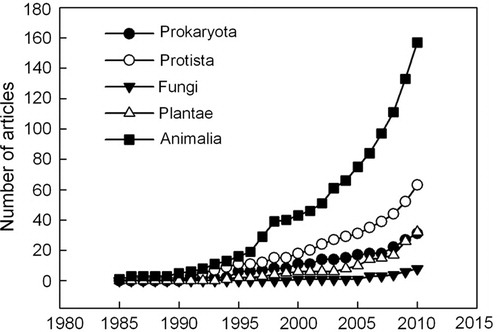

We found that 54% of the articles focused on Animalia, 22% on Protista, 11% on Plantae, 11% on Prokaryota and only 3% on Fungi (). Across the two time periods, articles concerning Animalia increased at the highest rate (± SD) with 23.3±6.4, followed by Protista (9.8±4.4), Prokariota (6.1±3.2), Plantae (3.9±3.5) and Fungi (1.6±4.3). In the last 15 years, the increase in the number of articles on animals has been exponential, while for the other kingdoms it has been lineal ().

Fig. 3 Cumulative frequency of articles concerning ecology in Antarctica with Latin American authorship between the years 1985 and 2010, according to the taxonomic Kingdom to which the study species belong. As some articles concern species belonging to different taxonomic groups, these categories are not mutually exclusive.

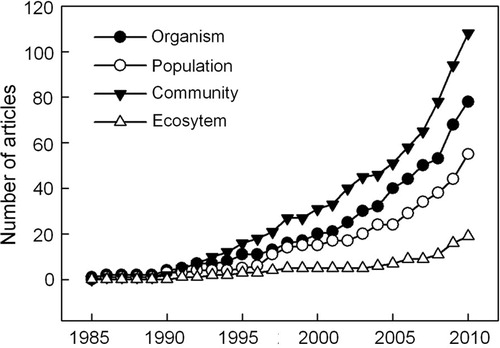

Most articles concerned the community level (42%), followed by studies of organisms (30%). Community- and organism-level articles showed the most marked rates of increase through time (geometric mean±SD of 16.2±3.97 and 14.0±2.91, respectively). Population studies accounted for 21%, with an increasing mean rate±SD of 9.5±3.26, and only 7% of articles concerned research carried out at the ecosystem level, with an increasing mean rate of 3.9±4.78 ().

Fig. 4 Cumulative frequency of articles concerning ecology in Antarctica with Latin American authorship between the years 1985 and 2010, according to the level of biological organization which the study examined.

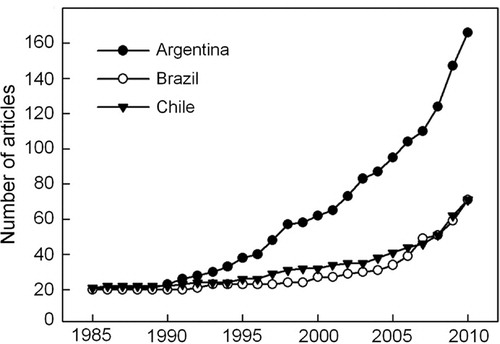

With regard to the publication trends of the three most productive countries, in the first 10 years (1985–1995) only 27 articles were published: 18 by Argentina, six by Chile and three by Brazil, which only started publishing in 1992 (). In the period 1995–2005, the three countries combined reached a total of 110 published articles, almost tripling the number of articles in the previous decade. In the last five years (2005–10), 138 articles were published. Argentina has almost three times as many papers as Chile (146 vs. 51) and also twice the increasing mean rate (geometric mean±SD) of Chile (Argentina: 19.8±2.5 vs. Chile: 9.4±2.5). Brazil has as many articles as Chile (51) but has a lower increasing mean rate (5.1±4.0; ).

Discussion

The main implication of our findings is that participation in Antarctic ecological research by Latin American countries increased substantially during recent decades. Refereed publications concerning polar research have been increasing at a rate that exceeds the rate of increase for science generally (Aksnes & Hessen Citation2009). Against this backdrop, Latin American authors have been continuously increasing their relative contribution to articles concerning ecological topics in Antarctica. This pattern is partially explained by an increase in collaboration with non-Latin American countries, with half of the collaboration articles being published in the last five years of the analysis (Aksnes & Hessen Citation2009; Benayas et al. Citation2013). However, given that 59% of the total articles were authored exclusively by Latin American scientists, the increasing trend is mainly explained by either greater involvement in Antarctic ecological research by Latin American countries or enhanced efforts by Latin American scientists to publish in international refereed journals instead of in local, smaller journals. In terms of collaboration, interestingly, even though the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia show the highest number of scientific publications on Antarctica (Dastidar Citation2007), Germany is the country that shows greater collaboration between Latin American countries. The low level of collaboration between Latin American countries and Australia and the United Kingdom is also remarkable (4 and 3% of the articles, respectively).

Fig. 5 Cumulative frequency of articles concerning ecology in Antarctica by authors with affiliations in the three Latin American countries (Argentina, Chile and Brazil) with the greatest amount of articles published on the subject between the years 1985 and 2010.

The rising Latin American productivity in terms of scientific article output is almost totally accounted for by three countries: Argentina, Chile and Brazil. It seems reasonable to relate the lead taken by Argentina and Chile to the relatively large number of facilities they have in Antarctica and the fact that these countries were involved from the beginning in Antarctic scientific and development initiatives, namely, the IGY and the Antarctic Treaty. Argentina was the first country to establish a year-round Antarctic base, in 1904 (Orcadas Station) and Chile (Arturo Prat Station) was—together with the United Kingdom (Signy Station)—the second one, in 1947 (COMNAP Citation2011). Argentina and Chile, with their territories extending to the southern tip of South America, are the countries with the closest historical links with the Antarctic continent in terms of the biota (Arntz Citation1999). Because of the 21 facilities Chile has in Antarctica, in contrast to the 14 from Argentina (COMNAP Citation2011), we expected Chile to have, at least, a similar number of articles as Argentina, not a third of it. This outcome may be explained by a greater number of Argentinean scientists involved in Antarctic ecological research and better funding for such research from Argentinean institutions, compared to Chile. Despite its second place compared to Argentina in terms of article output in ISI-indexed journals, Chile has shown a higher degree of engagement in international decision-making concerning Antarctica as measured by the number of working papers it has submitted. Presenting these papers is the formal way to raise matters for discussion at the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meetings. Between 1992 and 2010 Chile presented more working papers than all other Latin American countries (Dudeney & Walton Citation2012).

It is remarkable that Brazil, with a single facility in Antarctica, which was built after the Chilean ones, has produced the same amount of Antarctic research articles as Chile. Although Brazil's increasing rate of productivity is clearly lower than Argentina's, and lower than that shown by Chile, in view of its significant research capacity as a country and the latest trends, it is likely that Brazil will overtake Chile shortly. More output was also expected for the other Latin American countries. Among those countries grouped under “Others,” Uruguay and Peru have a year-round and a summer research station, respectively.

Results show that most articles concern studies conducted in marine environments. However, there is a slight tendency for an increase in articles reporting terrestrial studies. This is probably related to the greater biodiversity in the Antarctic marine ecosystems compared to the terrestrial ecosystem (Broyer et al. Citation2011). Although it is true that terrestrial biodiversity is comparatively low, it is also a fact that it has been poorly studied, and recent studies show that Antarctic terrestrial ecosystems may be much more biologically diverse than previously thought (Convey Citation2010Convey Citation2011). There is always less information about microorganisms when compared to plants and upper animals or chordates and this was reflected in the articles about animals showing the largest rate of increase. Plants were represented only by 11% of articles, probably because of their low diversity, especially in the case of flowering plants, which include only two species (Convey Citation1996).

Antarctic communities and food webs are functionally and structurally very simple (Freckman & Virginia Citation1997; Wall & Virginia Citation1999; Convey & McInnes Citation2005), which makes them ideal as study systems. This is probably why we found a high number, and increasing rate, of articles focused on the community level. Ecosystem-level research received less attention in the articles surveyed, and the rate of increase has been low.

It has been suggested that in Antarctic ecological research, a focus on the physicochemical basis of ecosystem structure and function has prevailed over studies of species interactions (Ainley et al. Citation2007). We think that it is of crucial importance to increase our understanding of Antarctic species, communities and ecosystems, so we can understand and foresee the effects of the environmental changes that are starting to occur. Antarctic climate is changing (Turner et al. Citation2005) and at a high rate (Vaughan et al. Citation2003; Turner et al. Citation2007). Climate change can not only have serious negative consequences for Antarctic organisms (Robinson et al. Citation2003; Hill et al. Citation2011; Nielsen et al. Citation2011) but it could also increase the probability of colonization by invasive species (Kennedy Citation1995; Frenot et al. Citation2005; Hughes et al. Citation2010; Molina-Montenegro et al. Citation2012). Currently, available information about Antarctica and its organisms is insufficient to assess the changes that will take place in the future (Wienecke Citation2011). Latin American countries could concentrate their efforts in gathering the information necessary to monitor these changes over time. This could be achieved especially if countries such as Chile and Argentina, with their privileged situation in terms of distance to study sites and number of facilities in Antarctica, cooperate with neighbouring countries lacking facilities in Antarctica.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Chilean Antarctic Institute's INACH T_14_08 and INACH G_22_11 projects for their funding support.

References

- Ainley D, Ballard G, Ackley S, Blichg L.K, Eastman J.T, Emslie SD, Lescroël A, Olmastroni S, Townsend S.E, Tynan C.T, Wilson P, Woehler E. Paradigm lost, or is top-down forcing no longer significant in the Antarctic marine ecosystem?. Antarctic Science. 2007; 19: 283–290.

- Aksnes D.W, Hessen D.O. The structure and development of polar research (1981–2007): a publication-based approach. Arctic Antarctic and Alpine Research. 2009; 41: 155–163.

- Arntz W. Magallan—Antarctic: ecosystems that drifted apart. Summary review. Scientia Marina. 1999; 63: 503–511.

- Auburn F.M. Consultative status under the Antarctic Treaty. International and Comparative Law Quarterly. 1979; 28: 514–522.

- Barnes D.K.A, Hodgson D.A, Convey P, Allen C, Clarke A. Incursion and excursion of Antarctic biota: past, present and future. Global Ecology and Biogeography. 2006; 15: 121–142.

- Beddings G. Peces en la Antártida Chilena. (Fishes in the Chilean Antarctica.). Boletín de la Sociedad de Biología de Concepción. 1949; 24: 91–99.

- Benayas J, Pertierra L, Tejedo P, Lara F, Bermudez O, Hughes K.A, Quesada A. A review of scientific research trends within ASPA no. 126 Byers Peninsula, South Shetland Islands, Antarctica. Antarctic Science. 2013; 25: 128–145.

- Berkman P.A, Lang M.A, Walton D.W.H, Young O.R. Science diplomacy: Antarctica, science and the governance of international spaces. 2011; Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press.

- Broyer C, Danis B, with 64 SCAR-MarBin Taxonomic Editors. How many species in the Southern Ocean? Towards a dynamic inventory of the Antarctic marine species. Deep-Sea Research Part II. 2011; 58: 5–7.

- Clarke A, Barner D.K.A, Hodgson D.A. How isolated is Antarctica?. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 2005; 20: 1–3.

- Convey P. The influence of environmental characteristics on life history attributes of Antarctic terrestrial biota. Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 1996; 71: 191–225.

- Convey P. Terrestrial biodiversity in Antarctica—recent advances and future challenges. Polar Science. 2010; 4: 135–147.

- Convey P. Antarctic terrestrial biodiversity in a changing world. Polar Biology. 2011; 34: 1629–1641.

- Convey P, McInnes S.J. Exceptional tardigrade-dominated ecosystems in Ellsworth Land, Antarctica. Ecology. 2005; 86: 519–527.

- COMNAP (Council of Managers of National Antarctic Programs). Antarctic facilities 2009. 2011. Accessed on the internet at https://www.comnap.aq/facilities on 26 September 2011..

- Dastidar P.G. National and institutional productivity and collaboration in Antarctic science: an analysis of 25 years of journal publications (1980–2004). Polar Research. 2007; 26: 175–180.

- Dastidar P.G, Persson O. Mapping the global structure of Antarctic research vis-à-vis Antarctic Treaty System. Current Science. 2005; 89: 1552–1555.

- Dudeney J.R, Walton D.W.H. Leadership in politics and science within the Antarctic Treaty. Polar Research. 2012; 31 article no. 11075.

- Freckman D.W, Virginia R.A. Low-diversity Antarctic soil nematode communities: distribution and response to disturbance. Ecology. 1997; 78: 363–369.

- Frenot Y, Chown S.L, Whinam J, Selkirk P.M, Convey P, Skotnicki M, Bergstrom D.M. Biological invasions in the Antarctic: extent, impacts and implications. Biological Review. 2005; 80: 45–72.

- Gotelli N.J, Ellison A.M. A primer of ecological statistics. 2004; Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, Inc.

- Gould L.M. Antarctica—continent of international science. Science. 1965; 150: 1775–1781.

- Hack W.H. Nota sobre un colémbolo de la Antarctica Argentina Achorutes viaticus Tullberg. (Note on a springtail from the Argentinian Antarctica, Anchorutes viaticus Tullberg.). Notas del Museo de La Plata. 1949; 14: 211–212.

- Hermosilla R.W. Conservación de los recursos vivos en la Antártica. (Conservation of the living resources in Antarctica.). Instituto Antártico Chileno Boletín. 1970; 5: 19–20.

- Hill P.W, Farrar J, Roberts P, Farrell M, Grant H, Newsham K.K, Hopkins D.W, Bardgett R.D, Jones D.L. Vascular plant success in a warming Antarctic may be due to efficient nitrogen acquisition. Nature Climate Change. 2011; 1: 50–53.

- Hughes K.A, Convey P, Maslen N.R, Smith R.I.L. Accidental transfer of non-native soil organisms into Antarctica on construction vehicles. Biological Invasions. 2010; 12: 875–891.

- Kennedy A.D. Antarctic terrestrial ecosystem response to global environmental change. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematic. 1995; 26: 683–704.

- Larrain A.P. Brachysternaster, new genus, and Brachysternaster chesheri, new species of Antarctic Echinoid (Spatangoida, Schizasteridae). Polar Biology. 1985; 4: 121–124.

- Llaña A.H. Primera expedición Antarctica Chilena. Algas marinas. (First Chilean Antarctic expedition. Seaweeds.). Revista de Biología Marina. 1948; 1: 19–31.

- Mac Donagh E.J. Biología continental y oceánica de la Antártida. (Continental and oceanic biology of Antarctica.). Soberanía Argentina en el Archipiélago de las Malvinas y en la Antártida. (Argentinian sovereignty in the Falklands archipelago and in the Antarctic.). 1951; La Plata: Faculty of Law and Social Sciences, National University of La Plata. 95–118.

- Mann G. Biología de la Antártica Suramericana. (Biology of the South American Antarctic.). 1948; Santiago: Imprenta Universitaria.

- Molina-Montenegro M.A, Carrasco-Urra F, Rodrigo C, Convey P, Valladares F, Gianoli E. Occurrence of the non-native bluegrass on the Antarctic mainland and its negative effects on native plants. Conservation Biology. 2012; 26: 717–723.

- Moyano G.H.I. Bryozoa colectados por la Expedición Antártica Chilena 1964–65. 3. Familia Celleriidae Hinks, 1880. (Bryozoa collected from the Chilean Antarctic Expedition 1964–65. 3. Celleriidae family Hinks, 1980.). Sociedad de Biologia de Concepción Boletin. 1969; 41: 41–77.

- Nielsen U.N, Wall D.H, Adams B.J, Virginia R.A. Antarctic nematode communities: observed and predicted responses to climate change. Polar Biology. 2011; 34: 1701–1711.

- Olguin H.F, Alder V.A. Species composition and biogeography of diatoms in Antarctic and Subantarctic (Argentine shelf) water (37–76°S). Deep Sea Research Part II. 2011; 58: 139–152.

- Pannatier S. Acquisition of consultative status under the Antarctic Treaty. Polar Record. 1994; 30: 123–129.

- Robinson S.A, Wasley J, Tobin A.K. Living on the edge-plants and global change in continental and maritime Antarctica. Global Change Biology. 2003; 9: 1681–1717.

- Schlatter R, Hermosilla R.W, Di Castri F. Estudios ecológicos en la Isla Robert (Shetland del Sur) 2. Distribución altitudinal de los artrópodos terrestres. (Ecological studies in the Robert Island [South Shetland] 2. Altitudinal distribution of the terrestrial arthropods.). 1968; Punta Arenas: Chilean Antarctic Institute.

- Stuardo J, Solis I. Biometría y observaciones generales sobre la biología de Lithodes antarcticus. (Biometrics and general observations about the biology of Lithodes antarcticus.). Gayana Zoologia. 1963; 11: 1–52.

- Turner J, Bindschadler R, Convey P, Di Prisco G, Fahrbach E, Gutt J, Hodgson D.A, Mayewski P.A, Summerhayes C.P. Antarctic climate change and the environment. 2009; Cambridge: Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research.

- Turner J, Colwell S.R, Marshall G.J, Lachlan-Cope T.A, Carleton A.M, Jones PD, Lagun V, Reid A, Iagovkina S. Antarctic climate change during the last 50 years. International Journal of Climatology. 2005; 25: 279–294.

- Turner J, Overland J.E, Walsh J.E. An Arctic and Antarctic perspective on recent climate change. International Journal of Climatology. 2007; 27: 277–293.

- Vaughan D.G, Marshall G.J, Connolley W.M, Parkinson C, Mulvaney R, Hodgson D.A, King J.C, Pudsey C.J, Turner J. Recent rapid regional climate warming on the Antarctic Peninsula. Climate Change. 2003; 60: 243–274.

- Vyverman W, Verleyen E, Wilmotte A, Hodgson D.A, Willems A, Peeters K, Van de Vijver B, de Wever A, Leliaert F, Sabbe K. Evidence for widespread endemism among Antarctic micro-organisms. Polar Science. 2010; 4: 103–113.

- Wall D.H, Virginia R.A. Controls on soil biodiversity: insights from extreme environments. Applied Soil Ecology. 1999; 13: 137–150.

- Wienecke B. Review of historical population information of emperor penguins. Polar Biology. 2011; 34: 153–167.