Abstract

Egg masses of the Patagonian squid Doryteuthis (Amerigo) gahi attached to giant kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera) in the Magellanic channels of the sub-Antarctic ecoregion in southern South America is documented for the first time. Of seven egg masses observed between 2008 and 2011, one was taken to the laboratory to be analysed and photographed. Comprising long transparent capsules containing eggs, the masses were strongly attached to the stipes of M. pyrifera. This macroalgae is a potentially important economic resource due to its multiple industrial uses; this study shows that it also serves an important ecological role as a spawning substrate for D. gahi.

Coastal ecosystems in the Magellanic channels of the sub-Antarctic ecoregion (southern tip of South America) are heterogeneous environments with different types of biotypes (Soto et al. Citation2012) that include a great diversity of algae and molluscs (Santelices & Marquet Citation1998; Valdovinos et al. Citation2003). The macroalgae Lessonia spp. and Macrocystis pyrifera (Linnaeus) C. Agardh are one of the dominant groups of marine benthic flora, especially on rocky boulders and rocky shores in Magellanic Province (Mansilla & Ávila Citation2011; Martin & Zuccarello Citation2012). Macrocystis pyrifera has been identified as an ecosystem engineer in the region (Coleman & Williams Citation2002; Ríos et al. Citation2007), and it plays an important role in the reproductive biology of amphipods and fishes (e.g., Moreno & Jara Citation1984; Cerda et al. Citation2010).

The Patagonian squid Doryteuthis (Amerigo) gahi (d'Orbigny 1835) is a pelagic species that occurs from the Magellan region northward to southern Peru in thesouth-east Pacific Ocean and to the San Matias Gulf in the south-west Atlantic (Roper et al. Citation1984; Ibañez et al. Citation2005). It supports an important fishery on the Patagonian shelf (Jereb et al. Citation2010). Some studies have been conducted along the Chilean coast on its fisheries biology (e.g., Vega et al. Citation2001) and phylogenetics (Ibañez et al. Citation2012), but most biological studies of this species have been conducted in the south Atlantic (e.g., Barón Citation2001, Citation2003).

Around the Falkland Islands, D. gahi attach egg masses to the stipes of M. pyrifera and Lessonia spp. (Arkhipkin et al. Citation2000), but this spawning behaviour has not been reported in Chile or the fjords and channels in the Magellan region. The objective of this study was to determine if, in fjords and channels in the Magellan region, D. gahi also attaches its egg masses to M. pyrifera, which is abundant in this region and a potentially important economic resource.

Materials and methods

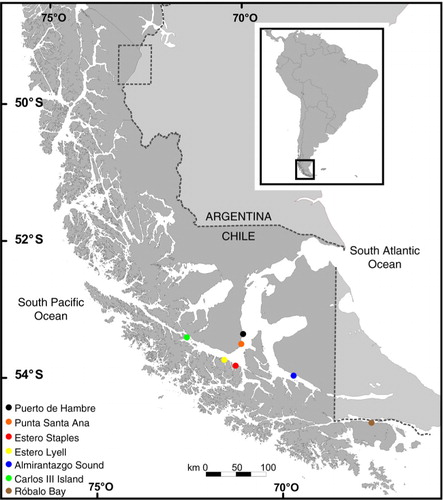

Egg masses were photographed attached to Macrocystis pyrifera at five locations in the Strait of Magellan, one location in Almirantazgo Sound, and one location in Beagle Channel (, ). Twenty-one egg capsules from one egg mass in the Strait of Magellan at Punta Santa Ana (53°37,7′S; 70°54,8′W) were collected and transported to the Laboratory of Antarctic and Sub-Antarctic macroalgae of the Universidad de Magallanes. Eggs were kept in 80-L aquaria with nearly constant air flow, salinity of 31, temperature of 8±1°C and a 12:12 photoperiod. To identify the egg masses, we randomly selected seven of the capsules and made the following measurements, in accordance with Barón (Citation2003) for Doryteuthis spp.: capsule length and weight, number of eggs in each capsule, egg diameter (mm) and number of dark chromatophores in the cheek patch area—two oval areas located at the posterior half of the ventral surface of the head (Vecchione & Lipinski Citation1995). Paralarvae were photographed using an Olympus SZ61 stereomicroscope (Tokyo, Japan) attached to Moticam 200 camera (Motic, Hong Kong, China). Measurements were made using Micrometrics SE Premium software.

Table 1 Dates and locations of Doryteuthis gahi egg masses observed attached to Macrocystis pyrifera.

Results and discussion

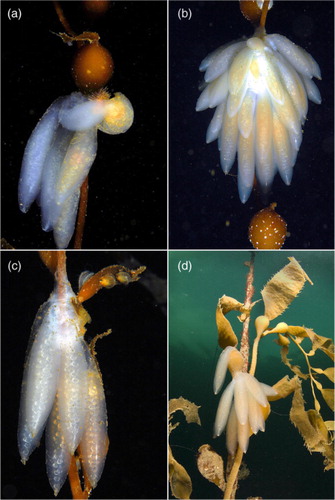

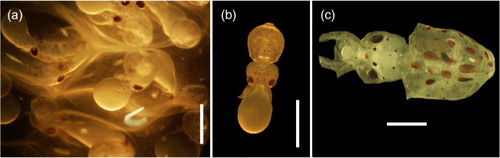

Seven egg masses (one at each location) were observed attached to Macrocystis pyrifera (). Egg capsules from the egg mass at Punta Santa Ana had an average length of 61±1.9 mm and an average weight of 5.6±0.6 g (n=7) (), and contained an average of 56±7 eggs (n=7), with an average egg diameter of 2.5±0.2 mm. Arkhipkin et al. (Citation2000) reported very similar measurements for this species with an average egg capsule length of 54.93±8.87 mm, an average number of 73±22.85 eggs and an average egg diameter of 2.0–2.5 mm. Most paralarvae had three to four chromatophores in each cheek patch. These measurements are similar to those reported for Doryteuthis gahi (Arkhipkin et al. Citation2000; Barón Citation2003), suggesting that the egg masses we observed were spawned by D. gahi.

Fig. 2 Egg masses of Doryteuthis gahi attached to Macrocystis pyrifera stipes. Egg masses (a) and (b) were collected at Estero Staples, (c) at Estero Lyell and (d) at Puerto de Hambre. (Photos by Mathias Hüne.)

Fig. 3 (a) Close-up of Doryteuthis gahi egg mass showing developing embryos; (b) D. gahi hatchling paralarva with attached yolk sac; (c) advanced paralarva. Scale bars are 1 mm.

This is the first report of D. gahi egg masses attached to M. pyrifera in the Magellanic channels of the sub-Antarctic ecoregion. Macrocystis pyrifera is a characteristic component of benthic ecosystems in this region (Mansilla & Ávila Citation2011). Charles Darwin observed these submarine forests during the Beagle expedition and noted their importance for the associated fauna (Darwin Citation1839). In this context, we highlight two aspects about the importance of M. pyrifera forests for the sub-Antarctic channel ecosystem: (a) their structural complexity could affect local conditions, such as currents and light intensity in the water column, resulting in increased biodiversity (Stachowicz Citation2001); (b) they provide a spawning substrate for invertebrates such as D. gahi that migrate into the calm waters in the interior of the channels to spawn.

Around the Falkland Islands, egg masses are found attached to stipes of both Lessonia spp. and M. pyrifera, but more often to Lessonia spp. (Arkhipkin et al. Citation2000; Brown et al. Citation2010). In our study, although M. pyrifera and Lessonia spp. were present at all locations, egg masses were found attached only to M. pyrifera. The congener Doryteuthis opalescens (Berry 1911) spawns in coastal water off California, where M. pyrifera is also present (Graham et al. Citation2007), but attaches its eggs to sandy substrate (Young et al. Citation2011). Doryteuthis gahi could be one of the few squid species that attaches its egg masses to kelp.

With diverse industrial uses, including providing phycocolloids in the form of alginate (Mansilla & Ávila Citation2011), M. pyrifera is a potentially important economic resource in the study region. Information is available about the biological basis for the sustainable exploitation of M. pyrifera (Mansilla et al. Citation2009), but caution is needed given that this kelp serves not only as a habitat for many animals but also as a spawning substrate for some benthic (e.g., gastropods) and pelagic (e.g., squid) species. This increases the ecological importance of conserving M. pyrifera forests.

Acknowledgements

SR acknowledges his scholarship from the Institute of Ecology and Biodiversity, Chile (code ICM P05-002) and his Master of Science in Conservations and Management of Sub-Antarctic Ecosystem at the University of Magellan. JO acknowledges his scholarship from the Institute of Ecology and Biodiversity, Chile (code P05-002). MH acknowledges his scholarship from the Institute of Ecology and Biodiversity, Chile (code PFB23-2008). AM would like to thank the AM Millennium Scientific Initiative (grant no. P05-002 ICM, Chile) and the Basal Financing Program of the Comisión Nacional de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica (grant no. PFB-23, Chile). The authors would like to thank the people of Patagonia Histórica S.A. for their valuable support to our fieldwork in Punta Santa Ana. The authors also thank two anonymous referees for their contribution in improving the manuscript.

References

- Arkhipkin A.I., Laptikhovsky V.V., Middleton D.A.J. Adaptations for cold water spawning in loliginid squid: Loligo gahi in Falkland waters. Journal of Molluscan Studies. 2000; 66: 551–564.

- Barón J. First description and survey of the egg masses of Loligo gahi (d'Orbigny, 1835) and Loligo sanpaulensis (Brakoniecki, 1984) from coastal waters of Patagonia. Journal of Shellfish Research. 2001; 20: 289–295.

- Barón J. The paralarvae of two South American sympatric squid: Loligo gahi and Loligo sanpaulensis. Journal of Plankton Research. 2003; 25: 1347–1358.

- Brown J., Laptikhovsky V., Dimmlich W. Solitary spawning revealed—an in situ observation of spawning behavior of Doryteuthis (Amerigo) gahi (d'Orbigny, 1835 in 1834–1847) (Cephalopoda: Loliginidae) in the Falkland Islands. Journal of Natural History. 2010; 44: 2041–2047.

- Cerda O., Hinojosa I.A., Thiel M. Nest-building behavior by the amphipod Peramphitho efemorata (Krøyer) on the kelp Macrocystis pyrifera (Linnaeus) C. Agardh from northern–central Chile. The Biological Bulletin. 2010; 218: 248–258. [PubMed Abstract].

- Coleman F.C., Williams S. Overexploiting marine ecosystem engineers: potential consequences for biodiversity. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 2002; 17: 40–43.

- Darwin C. Voyages of the Adventure and Beagle. Vol. III. Journals and Remarks. 1832–1836. 1839; London: Henry Colburn.

- Graham M.H., Vásquez J.A., Buschmann A.H. Global ecology of the giant kelp Macrocystis: from ecotypes to ecosystems. Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review. 2007; 45: 38–88.

- Ibañez C., Argüelles J., Yamashiro C., Adasme L., Céspedes R., Poulin E. Spatial genetic structure and demographic inference of the Patagonian squid Doryteuthis gahi in the south-eastern Pacific Ocean. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 2012; 92: 197–203.

- Ibañez C., Chong J., Gandarillas C. Relaciones somatométricas y reproductivas del calamar Loligo gahi Orbigny, 1835 en bahía Concepción Chile. (Somatometric and reproductive relationships of the squid Loligo gahi Orbigny, 1835 at Concepción Bay, Chile.). Investigaciones Marinas. 2005; 33: 211–215.

- Jereb P., Vecchione M., Roper C.F.E. Jereb P., Roper C.F.E. Family Loliginidae. Cephalopods of the world. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of species known to date. Vol. 2. Myopsid and oegopsid squids. 2010; Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 38–117.

- Mansilla A., Ávila M. Using Macrocystis pyrifera (L.) C. Agardh from southern Chile as a source of applied biological compounds. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia. 2011; 21: 262–267.

- Mansilla A., Ávila M., Cáceres J., Palacios M., Navarro N., Cañete I., Oyarzún S. Diagnóstico bases biológicas para la explotación sustentable Macrocystis pyrifera, (Huiro), XII Región Código BIP N° 30060262-0. 2009; Punta Arenas: Regional Government of the Magellan and Chilean Antarctic Region. (Biological basis for the sustainable exploitation of Macrocystis pyrifera [Huiro], XII Region BIP Code No. 30060262-0.).

- Martin P., Zuccarello G.C. Molecular phylogeny and timing of radiation in Lessonia (Phaeophyceae, Laminariales). Phycological Research. 2012; 60: 276–287.

- Moreno C.A., Jara F.H. Ecological studies of fish fauna associated with Macrocystis pyrifera belts in south of Fueguian Island, Chile. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 1984; 15: 169–178.

- Ríos C., Arntz W.E., Gerdes D., Mutschke E., Montiel A. Spatial and temporal variability of the benthic assemblages associated to the holdfasts of the kelp Macrocystis pyrifera in the Straits of Magellan, Chile. Polar Biology. 2007; 31: 89–100.

- Roper C.F.E., Sweeney M.J., Nauen C.E. Cephalopods of the world. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of species of interest to fisheries. 1984; Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Santelices B., Marquet P.A. Seaweeds, latitudinal diversity patterns, and Rapoport's Rule. Diversity and Distributions. 1998; 4: 71–75.

- Soto E., Báez P., Ramírez M.E., Letelier S., Naretto J., Rebolledo A. Biotopos marinos intermareales entre Canal Trinidad y Canal Smyth, Sur de Chile. (Intertidal marine biotopes between Trinidad Channel and Smyth Channel, southern Chile.). Revista de Biología Marina y Oceanografía. 2012; 47: 177–191.

- Stachowicz J.J. Mutualism, facilitation, and the structure of ecological communities. Bioscience. 2001; 51: 235–246.

- Valdovinos C., Navarrete S.A., Marquet P.A. Mollusk species diversity in the southeastern Pacific: why are there more species towards the pole?. Ecography. 2003; 26: 139–144.

- Vecchione M., Lipinski M. Descriptions of the paralarvae of two loliginid squids in southern African waters. South African Journal of Marine Science. 1995; 15: 1–7.

- Vega M., Rocha F., Osorio C. Morfometría comparada de los estatolitos del calamar Loligo gahi d'Orbigny, 1835 (Cephalopoda: Loliginidae) del norte de Perú e islas Falkland. (Compared morphometry of squid statoliths Loligo gahi d'Orbigny, 1835 [Cephalopoda: Loliginidae] of northern Peru and Falkland Islands.). Investigaciones Marinas. 2001; 29: 3–9.

- Young M., Kvitek R., Lampietro P., Garza C., Maillet R., Hanlet R. Seafloor mapping and landscape ecology analyses used to monitor variations in spawning site preference and benthic egg mop abundance for the California market squid (Doryteuthis opalescens). Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 2011; 407: 226–233.