Abstract

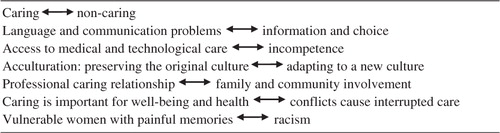

The aim of this study is to explore and describe a patient perspective in research on intercultural caring in maternity care. In total, 40 studies are synthesized using Noblit and Hare's meta-ethnography method. The following opposite metaphors were found: caring versus non-caring; language and communication problems versus information and choice; access to medical and technological care versus incompetence; acculturation: preserving the original culture versus adapting to a new culture; professional caring relationship versus family and community involvement; caring is important for well-being and health versus conflicts cause interrupted care; vulnerable women with painful memories versus racism. Alice in Wonderland emerged as an overarching metaphor to describe intercultural caring in maternity care. Furthermore, intercultural caring is seen in different dimensions of uniqueness, context, culture, and universality. There are specific cultural and maternity care features in intercultural caring. There is an inner core of caring consisting of respect, presence, and listening as well as external factors such as economy and organization that impact on intercultural caring. Moreover, legal status of the patient, as well as power relationships and racism, influences intercultural caring. Further meta-syntheses about well-documented intercultural phenomena and ethnic groups, as well as empirical studies about current phenomena, are suggested.

Introduction

The world is becoming more multicultural and the Nordic countries have more patients from different cultures. Culture in this study refers to “a pattern of learned but dynamic values and beliefs that gives meaning to experience and influences the thoughts and actions of individuals of an ethnic group” (Wikberg & Eriksson, Citation2008a, p. 486). Caring influences health and well-being and is established as an important part of nursing (Sherwood, Citation1997). Since there is an increasing amount of qualitative studies about caring, intercultural care, and maternity care for mothers from other cultures, there is a need to integrate research in this field in order to develop care. Although qualitative research is well recognized and has shown a substantive knowledge it has little impact for evidence-based practice (Bondas & Hall, Citation2007a). This type of research is needed in our multicultural society due to a lack of multicultural meta-syntheses (Bondas & Hall, Citation2007b). Therefore, it is interesting and necessary to collect and synthesize the knowledge available in published studies about a patient perspective on intercultural caring in maternity care. This knowledge is necessary in order to increase the understanding and discussion among politicians, scholars, and practitioners to improve practice. This study is part of a project called Encountering the unknown in health care at the Department of Caring Science at Åbo Akademi University.

2 Theoretical perspective

The theoretical perspective of this meta-ethnography is Eriksson's caritative theory and caring tradition (Eriksson, Citation1997Citation2002; Eriksson, Lindholm, Lindström, Matilainen, & Kasén, Citation2006; Lindström, Lindholm, & Zetterlund, Citation2006) where caring is seen as the core of nursing. According to Eriksson, caring maintains and enables health and well-being. The human being is seen as body, mind, and spirit. The patient is a suffering human being. Striving for genuine communion and understanding for the unique human being is essential. A caring relationship derives its origin from the ethos of love, responsibility, and sacrifice, i.e., a caritative ethic. The human being's dignity and holiness is placed first. The purpose of caring is to alleviate suffering and promote health and life. The aim of caring science is to understand meaning and find knowledge for alleviating suffering and serving life and health.

Wikberg and Eriksson (Citation2008a) have described a model for intercultural caring. In this model, intercultural caring is a mutual but asymmetrical relationship between a patient and a professional nurse from different cultures. Intercultural caring is described as different dimensions: ontological, phenomenological, and practical. Moreover, intercultural caring promotes health and well-being. The patient's acculturation and the nurse's cultural competence as well as the cultural backgrounds of both influence intercultural caring. Outer factors like education, politics, and organization also influence intercultural caring and all aspects of intercultural caring are seen as a whole. “Intercultural refers to mutuality and concentration on similarities and less on comparing cultural differences than transcultural and crosscultural concepts” (Wikberg & Eriksson, Citation2008a, p. 493). The theoretical perspective is used as a starting point, against which the findings are reflected.

3 Earlier meta-syntheses

Earlier meta-syntheses were searched for in Cinahl (Ebsco) and Pubmed with the words caring/transcultural/intercultural/maternity/childbirth/midwifery combined with meta-synthesis. Three meta-syntheses about caring for children (Aagaard & Hall, Citation2008; Beck, Citation2002a; Nelson, Citation2002) were not considered below. Meta-syntheses on maternity care have described postpartum depression (Beck, Citation2002b), the process and practice of midwifery care in the USA (Kennedy, Rousseau, & Low, Citation2003), transition to motherhood (Nelson, Citation2003), expectant parents difficulty of choice after receiving information about fetal impairment (Sandelowski & Barroso, Citation2005), expert intrapartum maternity care (Downe, Simpson, & Trafford, Citation2006) and breastfeeding (Nelson, Citation2006).

Coffman's (Citation2004) study about nurses’ experience of caring for patients from other cultures was the only meta-synthesis located within intercultural care. The qualitative studies included were reduced to the following six themes: connecting with the patient, cultural diversity, the patient in context, in their world not mine, road blocks, and the cultural lens. Sherwood (Citation1997) conducted a meta-synthesis on caring from the patient's perspective, and Finfgeld-Connett (2005) tried to clarify the concept of social support. In another meta-synthesis (Finfgeld-Connett, Citation2006), presence was described and Finfgeld-Connett (2008) synthesized qualitative research to enhance the understanding of caring in nursing.

The included studies in the above meta-syntheses were all published in English, a few (Beck, Citation2002b; Coffman, Citation2004; Nelson, Citation2006; Sandelowski & Barroso, Citation2005) included other cultures besides western cultures. Some excluded non-western studies (Nelson, Citation2003) or included only North American studies (Coffman, Citation2004; Kennedy, Rousseau, & Low, Citation2003; Sandelowski & Barroso, Citation2005) and some did not mention culture or ethnic groups in the choice of studies (Finfgeld-Connett, Citation2005Citation2006Citation2008; Sherwood, Citation1997).

Coffman's results concerned cultural issues throughout, according to the aim. In Beck's (Citation2002b) study, cultural aspects of the results are considered. Some did not mention cultural aspects in their results at all, while others were aware that culture might affect the results, but gave no examples, or were aware that their study was homogenous. In some studies, a western cultural perspective is implicitly seen in the results but not discussed. Several meta-syntheses were found on maternity care, caring or transcultural nursing, but no meta-synthesis from a patient perspective on intercultural caring in maternity care was discovered. Culture and ethnic groups are not always considered when including studies, non-English studies are ignored and the results reflect cultural aspects only to a slight extent.

4 Aim

The aim of this meta-ethnography was to explore and describe a patient perspective in research on intercultural caring in maternity care.

5 Method

The meta-ethnography method developed by Noblit and Hare (Citation1988) was chosen because it has the potential “for deriving substantive interpretations about any set of ethnographic and interpretive studies” (p. 9). Since the subject of this study, intercultural caring, is one concerning different cultures from an emic view, this method is especially suitable to collect, analyse, and interpret substantive knowledge. Meta-ethnography is also the most common method used for meta-synthesis in nursing science (Bondas & Hall, Citation2007a). Noblit and Hare's (Citation1988, pp. 26–29) meta-ethnography method includes seven phases that overlap and repeat as the synthesis proceeds:

Getting started includes deciding what the study is going to be about or in other words what the aim is.

Deciding what is relevant to the initial interest. This includes how studies are searched for and the criteria for inclusion and exclusion.

Reading the studies repeatedly, analyzing and noting interpretative metaphors. Here metaphors mean themes, perspectives, organizers, and/or concepts.

Determining how the studies are related. There are three ways the studies can be related: (1) the accounts are directly comparable as “reciprocal” translations; (2) the accounts stand in relative opposition to each other and are essentially “refutational”; or (3) the studies taken together present a “line of argument” rather than a reciprocal or refutational translation (Noblit & Hare, Citation1988, p. 36).

Translating the studies into one another. Translation is the same as “interpretative explanation” (Noblit & Hare, Citation1988, p. 7). Uniqueness and holism of studies can be retained even if the accounts are synthesized in the translations.

Synthesizing translations is to create a new whole of the parts. This is where a second or higher level synthesis is possible.

Expressing the synthesis in written or other form.

5.1 Literature search

Published research has systematically been searched for from March 2008 until March 2009, through homepages, databases, references, authors, and journals. The homepages of the Transcultural Nursing Society, Transcultural C.A.R.E. Associates, European Transcultural Nursing Association (ETNA), Cultural Diversity in Nursing, Transcultural Nursing, and CulturedMed were searched. The last mentioned provided the most results. The words care/caring/uncaring/non-caring have been combined with transcultural/intercultural/multicultural/crosscultural/ “from cultures other than their own” and maternal/maternity/mother/birth/childbirth/childbearing/delivery/confinement/labour/labor/midwifery/midwife/antenatal/prenatal/postnatal/perinatal/pregnant/pregnancy/obstetric, and shorter forms of these with an asterisk on 14–17 databases, depending on whether they were available or not on Nelli, which is a Finnish portal. The databases were Blackwell Synergy/Cinahl (Ovid)/ebrary/Health and Safety Science Abstracts (CSA)/IngentaConnect/Intute/Journals@ovid/Medic/Medline (CSA)/Medline (Ovid)/Pubmed/SAGE Journals Online (Sage premier)/ScienceDirect (Elsevier)/SpringerLink/Web of Science (ISI)/Academic Search Premier (EBSCO)/Arto. The Finnish databases (Arto and Medic) were searched with similar words in Finnish and Swedish. The titles of articles in the following journals: Midwifery 1985–2008/2, Journal of Midwifery and Women's Health 2000–2008/6, Cultural Diversity 2003–2008/2, Ethnicity and Health 1996/3–4–2008/5, Birth 1998–2008/3, Maternal and Child Health Journal 2005–2009/1 have systematically been searched. All the reference lists as well as the names of the first authors of included articles have been searched. A manual search has also been made.

First the titles were checked. Interesting titles led to abstracts and interesting abstracts gave full text articles. After reading 149 full text articles, 19 articles were included, 32 unclear articles were reread and discussed with the second author, and thereafter a total of 40 articles were included (). One hundred and nine articles were excluded because they were not compatible with the inclusion criteria below.

Table I. Studies describing intercultural caring in maternity care included in meta-synthesis.

5.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria have been used. Scientific qualitative empirical articles in English, German, Finnish, Swedish, Norwegian, and Danish about intercultural caring in maternity care context from a patient perspective, published before the end of 2008 were included. If articles had several perspectives or designs (woman/patient and other, qualitative and quantitative) it had to be possible to separate the results. All ethnic groups were included. Exclusion criteria were very short articles (1–3 pages), theoretical and discussion articles as well as reviews, masters’ theses, and editorials. Articles that described caring in one culture, compared different cultures but did not include intercultural caring, or articles that compared patient's with professional's views were excluded. Studies about problems, diseases, religion, pain, health or communication or other subjects were excluded. The perspectives of students, teachers, or relatives were excluded. Quantitative studies were excluded. Duplicates that were based on the same sample and material and had the same aim were excluded. Subcultures and other nursing contexts than maternity care were excluded.

Dissertations have been excluded, partly because they are difficult to find and get hold of and partly because articles are usually published based on the dissertation. Unpublished theses and dissertations have not necessarily undergone the same rigorous evaluation as scientific articles in the peer review process. The same applies to research reports. Sandelowski and Barroso's (Citation2007, pp. 75–131) appraisal of qualitative research has been kept in mind when evaluating and choosing relevant articles for the study.

5.3 Analysing and synthesizing

Each article was read several times in full and its substance was analysed and expressed in metaphors (themes), which were written down with their description and examples. The metaphors emerged primarily in the results and findings of the articles. Metaphors from each article were translated (interpretatively explained) into common metaphors from other articles trying to preserve the uniqueness and holism of each article. The common metaphors that emerged were found to be opposites of each other (refutational). After articles were compared for similarities and differences, a higher level interpretation took place about the whole (the opposite metaphors and the findings in the 40 studies) (Noblit & Hare, Citation1988, pp. 62–64) and new interpreted results emerged to create a synthesis. Quotations were used for validations. The steps of the method overlapped.

6 Ethics

Although ethical issues have been considered in the included studies, ethics here is primarily concerned with choosing to synthesize an important field of study that has not previously received adequate attention. The studies are carefully analysed and synthesized to avoid unnecessary harm or devaluation of them. The intention is to find their deeper essence and to be critical in a constructive way (cf. Sandelowski, Docherty, & Emden, Citation1997, p. 370). Ethics is also to realize that the studies have been done and were published in their context and time. The recommendations of the National Advisory Board on Research Ethics (Citation2002) are followed.

7 Summary and context of included articles

This meta-synthesis consists of 40 articles published between 1988 and 2008. Eleven were made in the USA or Canada, 10 in the UK, eight in Australia, eight in Scandinavian countries, and one each in Israel, Japan, and South Africa (see ). There are more than 1160 women from more than 50 cultures involved. The sample varies between 5 and 388 women. Although the studies are published mostly in nursing journals, some were found also in medicine, public health, and psychology journals. There are six studies that are both quantitative and qualitative. In these only the qualitative result has been used. Three studies (Rice & Naksook, Citation1998; Small, Rice, Yelland, & Lumley, Citation1999; Woollett & Dosanjh-Matvala, Citation1990a) have the same sample as another study (Rice, Naksook, & Watson, Citation1999; Woollett & Dosanjh-Matvala, Citation1990b; Yeo, Fetters, & Maeda, Citation2000). The first two pairs of studies have divided antenatal/birth and postnatal into two studies and the third pair has different aims. These samples are only counted once above. All the studies had different kinds of interviews as the data collecting method. Some also had observations, field visits, or questionnaires. The most common methods of analysis were ethnography (10), content analysis (8), and grounded theory (6). Many mentioned thematic analyses.

The context in all the studies was either prenatal, birth, or postnatal care or a combination of these. All of the women with a few exceptions received care from professionals from another culture. The women in this study were heterogenic. The reason for immigration or entry into another culture varied. Some were illegal immigrants, asylum-seekers, refugees, temporary, or permanent immigrants because of studies, work, marriages, or other reasons. Although most had husbands or partners from the same culture, some were single or married to men from other cultures. The length of their stay and acculturation varied from recently arrived to second or more generation immigrants. Three studies (Maputle & Jali, Citation2006; Morgan, Citation1996; Reid & Taylor, Citation2007) examined “original” minority ethnic groups in a country. Language skills and educational (illiterate to university degree) background varied between the women. Their economical situation and insurance situation was also different. Some were alone while others had support from family and/or friends. Access, organization, and the cost of maternity care differed in the countries they resided.

8 Findings

The accounts in the studies are determined to stand in relative opposition to each other and are thus essentially “refutational.” The following seven opposite metaphors are found in the data (see ). These opposite metaphors, however, are not entirely exclusive of each other. For example, racism can be seen as part of non-caring.

8.1 Caring versus non-caring

Although there are many descriptions of caring, there is also non-caring. Professional caring is described as kindness, feeling cared for and releasing worries (Nabb, Citation2006), professional knowledge, personal touch meaning concern for protection, being attentive to and explaining, presence, respect for culture, religion, and family (Berry, Citation1999), something more than the routine (Bulman & McCourt, Citation2002) and continuity (McCourt & Pearce, Citation2000). Patients want respectful and not condemning care:

I was lucky when I met a midwife in Sweden who knew about circumcised women. This was a great help to make me feel secure because it was my first time to be pregnant and to live far from my parents and family. (Lundberg & Gerezgiher, Citation2008, p. 219)

8.2 Language and communication problems versus information and choice

In almost all the studies, language or communication problems are described. Even if there are obvious language and communication problems, patients are expected to be informed and make choices. Language problems influence all aspects of care (Yeo et al., Citation2000). It might be the language that is unknown, use of interpreter, communication styles or unwillingness to talk that causes the problems. Communication is essential for the relationship and caring to occur. “They don't give enough attention if you can't speak English …” (Woollett & Dosanjh-Matwala, Citation1990a, p. 183). Women often experience that they are not informed and therefore cannot choose. Sometimes patients do not want to tell the nurses about their problem because it is shameful, they don't want the nurse to lose face or it is taboo to talk about something. A Chinese woman (Cheung, Citation2002) felt pity for the midwife who tried to distract her in labor by talking about herself, her cat and husband when the woman was tired and had pain and wanted to rest. In Chinese culture it is not a tradition to keep pets and talk about husbands to strangers. The metaphor “don't hang your dirty laundry out” (Templeton, Velleman, Persaud, & Milner, Citation2003, p. 215) is used by patients who have postnatal depression for not disclosing. Knowledge of language and culture is not enough though for caring to occur (Ny, Plantin, Karlsson, & Dykes, Citation2007).

Patients who do not know what is happening during labor are often very scared and frustrated. One woman did not know if she had been given information about the progress of her labor, “// they might have (told me). I didn't understand” (Davies & Bath, Citation2001, p. 241). Sometimes misunderstandings or conflicts occur because of language and communication problems and there are suspicions that unnecessary cesarean sections are done or patients are left without necessary care. Sometimes patients do not know enough about different choices or have no tradition of choosing, like this Chinese mother. “There are so many choices and I have never tried any of them before. I haven't got any personal experience about them. I have no idea what to choose …” (Cheung, Citation2002, p. 205). Information is not given about cultural issues like male circumcision, which is required in Islam for male infants. “They don't know anything about it. They will tell you that you have to ask your doctor” (Reitmanova & Gustafson, Citation2008, p. 106). Although information is wished for and needed, it can be frightening to receive it (Ny et al., Citation2007).

8.3 Access to medical and technological care versus incompetence

In many of the studies women are very thankful of the good care they have received. They think that the hygiene, material equipment, and technical knowledge are supreme to their home countries (Tsianakias & Liamputtong, Citation2002). They trust the doctors’ assessments (Beine, Fullerton, Palinkas, & Anders, Citation1995; Liamputtong & Watson, Citation2006) or appreciate the medical knowledge and safety of childbirth “… it is safer in hospital” (Cheung, Citation2002, p. 207). “… They are very capable and professional. The Norwegian health care system is very good and efficient” (Nøttveit, Citation2000, p. 48).

At the same time many patients experience professionals’ incompetence, e.g., about female genital mutilation (FGM) and its care, religious matters, different traditions, and treatment policies. Here a Somali woman talks about Swedish midwives’ incompetence to care for circumcised women:

I and other women who have not been opened before delivery suffer most. We need to be opened at delivery, but the midwives don't know how to cut. They wait until the head of the baby is down and then they cut in a hurry in all directions, often several cuttings. They are not careful. I think that they see us as already destroyed. (Berggren et al., Citation2006, p. 54)

8.4 Acculturation: preserving the original culture versus adapting to a new culture

Patients and their families want to preserve some of their culture and adapt other parts to the majority culture. Somalis, for example, get changed gender roles. Fathers start to take part in the delivery and help more after delivery, which some women experienced positively with more understanding or love from the husband, while others experienced loss of areas of responsibility (Essén et al., Citation2000; Wiklund, Aden, Högberg, Wikman, & Dahlgren, Citation2000). Some start to use contraceptives and have fewer children (Wiklund et al., Citation2000). Hmong women begin to bottle feed their babies for different reasons, even if they have breastfed their babies before they came to the USA (Jambunathan & Stewart, Citation1995). Japanese and Somali women are reluctant to have epidurals and other pain treatment during labor, but like the pain relieving effect. In addition, hospitals and professionals change. Some changes are positively received by patients, like diet and language help but others are not liked, e.g., shorter postnatal hospital stay. Sometimes women are forced to do things they do not want to do. Here a Filipino woman wanted to follow her tradition but the nurses want her to adapt:

The thing is we have to follow their practices here. They treat you all the same way, whatever country you come from anyway. So if they say “take a bath,” you take a bath … Of course you are not satisfied. (Small et al., Citation1999, p. 92)

8.5 Professional caring relationship versus family and community involvement

The relationship between the patient, in this case the women and their caregiver (nurses, midwives, or doctors) is prerequisite to caring.

She was a nice kind nurse. If I couldn't take something she would help me take it. I was bleeding and had a blood transfusion. When the blood stopped, she always looked and started it again, and in the morning she washed my face … she was really very kind. She's the one I won't forget. (Bulman & McCourt, Citation2002, p. 373)

The women's mothers were the most supportive persons; others were sisters, mothers-in-law, sisters-in-law, aunts and grandmothers; some of these women were geographically distant. The father of the baby was supportive of many, but by no means for all, of the women. (Pearce, Citation1998, p. 357)

8.6 Caring is important for well-being and health versus conflicts cause interrupted care

Caring is presented as preserving and promoting well-being and health. Especially culturally specific or congruent caring is seen as promoting well-being. Presence and protection is part of well-being and health by African American women. “Prenatal care ‘protects the mother and the baby’” (Morgan, Citation1996, p. 6). If the Asian women in Liamputtong and Watson's (Citation2006) study were not able to follow traditional practices, they believed it could have a severe affect on their future health.

However, many reasons for conflicts exist because of different expressions of caring, different traditions and care and treatment regimes that relatively often lead to an interruption of health care relationships or care altogether. These have negative consequences for health and well-being. In Chinese culture, postpartum is considered a cold state and, therefore, exposure to cold and wind like taking a shower, drinking iced water, and exposure to air conditioning are considered taboo. In Australian maternity hospitals this cause conflicts because “… unwillingness to shower was often regarded as unhygienic and evidence of uncooperative behaviour” (Chu, Citation2005, p. 47). “… In Sweden the fear (of cesarean section) could lead women to avoid seeking care when obstetrical problems and cesarean section might occur. This could lead to an increased risk for adverse outcome” (Essén et al., Citation2000, p. 1511). If the care is not personal, the women are not willing to take part in it and become quiet and passive (Granot et al., Citation1996; Tandon, Parillo, & Keefer, Citation2005). Some women leave hospital early because they misunderstand the hospital policy, are told to go home early, feel lonely, are asked by relatives to come home, want to help at home or are unable to follow dietary or other traditions (Rice et al., Citation1999) or do not get enough rest or help with childcare or breastfeeding in hospital (Woollett & Dosanjh-Matwala, Citation1990a; Yelland et al., Citation1998).

8.7 Vulnerable women with painful memories versus racism

Many of the women are described as vulnerable and lonely. Some are marginalized and isolated. They feel fear and anxiety during pregnancy and childbirth (Lundberg & Gerezgiher, Citation2008). Many have painful memories when visiting healthcare professionals or hospitals. They remember circumcision, torture, rape, previous offensive situations, and can experience it again.

When I go to the hospital, a picture comes to me. I remember what she did to me long ago back in Somalia, when I was only 7 years old. I see the features of her face and the razor she was going to cut me with. I remember it all. (Berggren et al., Citation2006, p. 53)

… I was so fearful of death during the labor process. I was afraid that I was going to die because in Cambodia, I used to see women die whilst giving birth, and I did not know the reason for their death. (Liamputtong & Watson, Citation2006, p. 69)

These vulnerable women who need caring, instead often meet indignity caused by the staff. Many experience that professionals had stereotypes about their culture or experience racism or discrimination.

… I would advice them (health care providers) to get to know us first because some of us are educated and some of us are not. We are totally mixed—just like them. They should wait before treating us like primitive people. (Herrel et al., Citation2004, p. 347)

… She looked at me like this and said, “Your are OK”… She said to another midwife, “These Africans … they come here, they eat nice food, sleep in a nice bed, so now she doesn't want to move from here!” … When she said this I didn't say anything, I just cried—she doesn't know me, who I am in my country. And the other midwife said “What's wrong with them, these Africans?” and some of them they laughed. (McLeish, Citation2005, p. 783)

8.8 The overarching metaphor

Alice in Wonderland was interpreted as the overarching metaphor with three aspects, when the opposite metaphors based on the findings in the 40 studies were reread and synthesized into a new whole. The metaphor Alice in Wonderland (a children's story by Charles Dodgson, alias Lewis Carroll, first published 1865, about a little girl who goes down a rabbit hole and comes to a land, full of strange creatures and curious adventures, where nothing, including herself, is like it used to be) is found in one of the studies (Sharts-Hopko, Citation1995) included.

When I learned that I would give birth in a foreign country, I was scared to death. I thought only in the US would I be able to have a baby and that in a foreign country everything would be done backward. (Sharts-Hopko, Citation1995, p. 345)

8.9 Intercultural caring has different dimensions: uniqueness, context, culture, and universality

Caring is described as unique to each woman, as person-centered or individual. The maternity context has some common features like the process of pregnancy, childbirth, and postnatal period, pregnancy and childbirth as normal events in life, breastfeeding, transition to motherhood, changed relationships, labor pain, and fear of labor and closeness between life and death. Childbirth is seen as going into a tunnel, where the woman does not know if she is going to survive or not (Vangen, Johansen, Sundby, Traeen, & Stray-Pedersen, Citation2004, p. 33). Common is also anxiety for the health of the child (Pearce, Citation1998) and in most studies female professionals or friends are preferred or missed. Childbirth is described as women's business (Reid & Taylor, Citation2007, p. 253), female business (Wiklund et al., Citation2000) or woman's world, and female network (Ny et al., Citation2007).

Culture also has common or specific characteristics. The women belong to different religions. Devotion to a God or fear of evil spirits is mentioned in some studies. FGM is causing special needs and care in Somali and Eritrean women. Asian, Somali, and Traveller women have special needs for practical help during postpartum, especially with childcare since they are used to a tradition of a 30–40 days resting period after birth. Several Asian cultures have special needs for diet, according to the hot and cold theory, during pregnancy and postpartum. Women from Somalia do not like interventions like ultrasound, contraceptive advice, and cesarean section (Beine et al., Citation1995). Hmong women do not like to be touched because they think it can cause a miscarriage (Jambunathan & Stewart, Citation1995). Cultural rules like not seeing the husband or the husband's other wife during labor, fasting during Ramadan, traditional medicines, treatments, and customs (e.g., herbs, moxabustion, roasting, steam bath, prayer, and amulets) exist in specific cultures to safeguard the health and well-being of the baby and mother. Childbirth and immigration are seen as a double burden with dual demands (Sharts-Hopko, Citation1995).

There are also universal expectations of caring like listening, presence, respect, concern, being kind, trying to understand. Ethnic minority women share many similar fundamental values and hopes of the health care service with the majority population (McCourt & Pearce, Citation2000).

8.10 Intercultural caring has an inner core of caring and is affected by outer factors

The universal part of intercultural caring is the inner core of caring. When patients experience kindness from nurses and doctors who listen, give time and are concerned, they feel respect, trust, love, and caring. This inner core of caring is independent of context and culture.

Lack of transport, interpreters, and babysitting means that some patients have difficulty coming to clinics and hospitals. A lack of time spent with clients, communication barriers and long waits in the clinic adversely affect the experienced caring (Morgan, Citation1996). Busy wards and midwives’ other duties prevent them from being with the patients (Maputle & Jali, Citation2006). Inflexible schedules and rigid rules make care difficult to attend to. Economy is a major concern for the women in the USA. The organization of maternity care as well as midwives’ education and rights to work are different in different countries. It is difficult for the women to know what kind of care they can get from whom and from where. Status of immigration varies and influences the access and security the women have.

8.11 Intercultural caring is influenced by legal status and power

Disempowerment (Reid & Taylor, Citation2007; Vangen et al., Citation2004), control (Cheung, Citation2002), and legal status (McLeish, Citation2005) have an important and profuse influence on caring and health, on both a personal and a societal level. It seems that the most vulnerable women with illegal, asylum-seeking, refugee status or from traditionally not accepted minorities or immigration for arranged marriage have the most difficult situation in accessing healthcare and encountering nurses, midwives, and doctors in maternity care. These women are also the ones with many traumatic memories in their background and are sometimes refused healthcare or interrupt their care when met with racism or offensive behavior even if they have health problems. They do not know the language and feel powerless, disempowered, and not in control when not knowing what is happening, not being listened to and not being able to influence the situation. As a result women become silent, passive, and avoid or interrupt the care. Disempowerment, experienced as non-caring can lead to an increased risk of not experiencing well-being and health (Essén et al., Citation2000). Negative experiences of prenatal care, including disempowerment, among low-income women across ethnic groups raises concern for the quality of care and long-term consequences (Wheatley, Kelley, Peacock, & Delgado, Citation2008). Empowerment is experienced when the culture is acknowledged and the woman can use practices from her own culture (Ito & Sharts-Hopko, Citation2002).

9 Discussion

The findings in this meta-synthesis explore and describe a patient perspective on intercultural caring in maternity care in 40 qualitative articles. The results show that intercultural caring in maternal care is complex. There is diversity among the women as well as similarity within context, culture, and caring. There are common parts of caring among all people (cf. Eriksson, Citation2002; Leininger, Citation2006) and in maternity care but each culture also has specific features important to intercultural caring. Furthermore, the unique woman's wishes and needs have to be considered since there are variations within and between cultures and every individual needs unique care (cf. Leininger, Citation2006). There are many opposite experiences of the women that receive maternity care from health care professionals from a different culture than themselves. They have both complex and paradoxal caring and uncaring experiences. Both inner core and outer factors affect the intercultural caring and health and well-being of the mother and baby. The legal status of the patient, disempowerment, racism among health care professionals and outer factors have huge influence on access to health care, the experience of caring and on the health and well-being of the patient (cf. Coffman, Citation2004; Wikberg & Eriksson, Citation2008b). It is not enough with education of nurses and doctors, there has to be positive attitude to and accepting of different cultures.

The 40 included studies are qualitative but they are influenced by quantitative thinking, e.g., results are often quantified. The sampling methods for the recruitment of informants in the included studies varied. Interviews vary in length, amount, and type. Most studies have considered ethical issues. Most studies describe the results in categories or themes with quotations as validation. Some studies had other informants than mothers. Theories influencing the studies were stated theories, e.g., Leininger's theory, or were implicit in the studies. The problem thinking/searching in ethnic groups/cultures could be seen in the studies and might have influenced the results. It was, for example, mentioned in several studies that immigration and childbirth (including circumcision, pain, and maternal care) were a double burden (Berggren et al., Citation2006) or a dual demand (Sharts-Hopko, Citation1995), but it was less emphasized that some women experienced childbirth in another country as a relief, feeling safe, and cared for by a competent personnel. Many of the studies give examples of non-caring as well as caring. Caring is often expressed as non-caring, which is important to understand for finding the missing parts of caring (Leininger, Citation1991).

The recommendations of including 10–12 studies in a meta-synthesis (Paterson, Thorne, Canam, & Jillings, Citation2001; Sandelowski & Barroso, Citation2007) are far exceeded. However, the breadth of the 40 studies included, which enabled interpretation beyond single studies as well as saturation, ensured that a more comprehensive consideration of the aim, including both preconditions and consequences, relationships between parts and opposites of caring, was possible. Meta-synthesis like this study can contribute to evidence-based care from a lifeworld perspective in midwifery care (Berg et al., Citation2008). Quantitative studies were excluded because the results are not comparable with qualitative results. The qualitative part, used in the studies that had both quantitative and qualitative findings, could possibly have been excluded because they had only a few open-ended questions superficially analysed. However, inclusion meant that they brought both width and saturation to the other studies. Three studies (Jeppesen & Tamer, Citation1988; McLeish, Citation2005; Nabb, Citation2006) did not state the analysing method but had arranged the results in themes.

Both the authors of this article have international work experience in care, research, and education. The first author has worked in Zambia, Lesotho, Nepal, and Vietnam during a 10-year period. Both the authors have worked in other Nordic countries and also have international contacts. Both belong to the Swedish-speaking minority in Finland. This has sensitized the authors to cultural and language questions in nursing care. This study includes studies about caring between several cultures done in several countries. An inclusion criterion was studies in several languages, which has earlier been missing (Bondas & Hall, Citation2007aCitationb), though only one in Danish was included. Meta-synthesis is at least three times interpretation (Bondas & Hall, Citation2007b), which affects the result. Although the original raw data is not available, the studies are. The accounts in this study were refutational; a type of meta-ethnography that has not been described to our knowledge in previous meta-synthesis studies (Bondas & Hall, Citation2007b).

9.1 Implications for clinical care

Health care professionals need to learn more about specific cultures and phenomena, especially the ones that they encounter most often. Professional interpreters of the same sex need to be available and used without cost for the patient. Without a common language or functioning communication, there can be no relationship between the patient and nurse, where caring can occur. The importance of relationship in maternity care is confirmed by Hunter, Berg, Lundgren, Ólafsdóttir, and Kirkham (Citation2008). Continuity of care also seems to be an advantage for women from other cultures because it helps in building trust. Professionals with knowledge of several languages and experience from working in other cultures need to be employed. Female professionals are preferred in maternity care. The professionals need to ask the women about their culture and their needs and show that they care. They need to inform the women and let them choose. Professionals need to be aware of their own culture and other cultures, traditions must be respected and majority culture not forced upon patients. Not only does a lack of education lead to incompetence among health care professionals but also organizations and societies are sometimes racist or discriminating against women. An effective system to combat discrimination, racism and stereotypes to avoid ill-being and negative outcomes of childbirth is often missing. Cultural competence might not be enough because there is a risk for categorization and stereotyping when differences are focused upon. Cultural safety, suffering because of differences and an appreciation of common humanity should also be considered (cf. Baumann, Citation2009).

Circumcised women do not get optimal care. Apart from a lack of awareness and knowledge and legal issues about circumcision, some midwives and doctors have no practical skills how to manage delivery and do not know when, where and how to cut. Knowledge about diet and traditional beliefs like hot–cold theory is often missing. Many women, especially Asian and African, want more help after delivery with childcare, household tasks, and personal needs to be able to rest and recover. For some women it is a double burden to adapt to a new culture at the same time as to deliver a baby and adapt to motherhood. Especially lonely women with traumatic backgrounds and an unsure legal status are vulnerable and at risk of depression and feelings of abandonment after delivery. These women who often miss their family and community support would need female supporters from the same cultures to help them during pregnancy, delivery, and the postpartum period. In addition, support groups after delivery are beneficial. Resources like interpreters, childcare, transport, diet, material in different languages and human resources are needed and enable intercultural caring.

Some practices in maternity care are influenced by western culture, e.g., rooming-in might not fit Asian or other women who have a tradition of resting and getting practical help with childcare after delivery (Rice, Citation2000). Therefore, flexibility must be observed because this might otherwise cause conflict with midwives/nurses or with family. All cultures do not have the same autonomy concept as western cultures. Some women might be used to paternalism or second order autonomy and want the midwife/doctor or family members to choose for them (Hanssen, Citation2004; Meddings & Haith-Cooper, Citation2008). For women who have no support from a family and social network, the midwife might be the only person to confide in (Berggren et al., Citation2006). If reciprocal caring is missing there is a risk for isolation and unnecessary suffering (Finfgeld-Connett, Citation2005).

9.2 Future studies

Many studies about circumcised women, health, acculturation, postnatal depression, pain, and suffering were excluded from this study. These and other studies in midwifery about ethnic groups like Somalis, Vietnamese, African American, and Spanish Americans could be interpreted in new meta-syntheses in the future. This study raised new questions about acculturation, disempowerment, and suffering because of immigration or ethnic affiliation.

10 Conclusions

This study, with Eriksson's caritative theory as its starting point, has widened the knowledge about a patient perspective on intercultural caring in a maternity context and added new aspects to the intercultural caring model (Wikberg & Eriksson, Citation2008a). This study has highlighted the importance of context and culture in supplement to the universal and the unique dimensions of caring. It has also shown the inner core as well as the importance of outer factors for the experience of caring by mothers in maternity care. Power, racism, and legal status have especially strong influence on how caring is experienced and on the result of the nursing and health care. In the intercultural caring model the relationship between patient and nurse is seen as reciprocal and asymmetric. Asymmetric means that the nurse had more responsibility, but it can as seen in this study also be misused as racism. Racism, discrimination, and intolerance often have support in organizations and political and legal structures of societies or outer factors. This study has highlighted cultural and social aspects of caring, human being, health, and suffering, which are not previously emphasized in the caritative theory. The dimensions of the intercultural caring model (ontological, phenomenological, and practical activities) have also been reformulated in a new and expanded way (universal, culture, context, and unique).

11 Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry to conduct this study.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the Department of Caring Science at Åbo Akademi University and BFiN, the qualitative research network Childbearing in the Nordic countries/Nordforsk. NordForsk and The Finland-Swedish Association for Nurses.

References

- Aagaard, H., & Hall, E. (2008). Mothers’ experiences of having a preterm infant in the neonatal care unit: A meta-synthesis. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. , 23 (3), e26–e36. Retrieved January 20, 2009. From http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0882596307000334.

- Baumann S. Beyond cultural competence. Nursing practice with political refugees. Nursing Science Quarterly. 2009; 22(1): 83–84.

- Beck C. Mothering multiples. The American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing. 2002a; 27(4): 214–221.

- Beck C. T. Postpartum depression: A metasynthesis. Qualitative Health Research. 2002b; 12(4): 453–472.

- Beine K. Fullerton J. Palinkas L. Anders B. Conceptions of prenatal care among Somali women in San Diego. Journal of Nurse-Midwifery. 1995; 40(4): 376–381.

- Berg M. Bondas T. Brinchmann B. Lundgren I. Ølafsdøttir Ø. Vehviläinen-Julkunen K, et al.. Evidence-based care and childbearing—a critical approach. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being. 2008; 3(4): 239–247.

- Berggren V. Bergström S. Edberg A.-K. Being different and vulnerable: Experiences of immigrant African women who have been circumcised and sought maternity care in Sweden. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2006; 17(1): 50–57.

- Berry A. Mexican American women's expressions of the meaning of culturally congruent prenatal care. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 1999; 10(3): 203–212.

- Bondas T. Hall E. Challenges in approaching metasynthesis research. Qualitative Health Research. 2007a; 17(1): 113–121.

- Bondas T. Hall E. A decade of metasynthesis research in health sciences: A meta-method study. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being. 2007b; 2(2): 101–113.

- Bulman K. H. McCourt C. Somali refugee women's experiences of maternity care in west London: A case study. Critical Public Health. 2002; 12(4): 365–380.

- Chalmers B. Omer-Hashi K. What Somali women say about giving birth in Canada. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 2002; 20(4): 267–282.

- Cheung N. F. Choice and control as experienced by Chinese and Scottish childbearing women in Scotland. Midwifery. 2002; 18(3): 200–213.

- Chu C. Postnatal experience and health needs of Chinese migrant women in Brisbane, Australia. Ethnicity and Health. 2005; 10(1): 33–56.

- Coffman M. Cultural caring in nursing practice: A meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Journal of Cultural Diversity. 2004; 11(3): 100–109.

- CulturedMed. (2008). Retrieved August 11, 2008, from http://culturedmed.binghamton.edu/.

- Davies M. Bath P. The maternity information concerns of Somali women in the United Kingdom. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2001; 36(2): 237–245.

- Downe S. Simpson L. Trafford K. Expert intrapartum maternity care: A meta-synthesis. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2006; 57(2): 127–140.

- Eriksson K. Understanding the world of the patient, the suffering human being: The new clinical paradigm from nursing to caring. Advanced Practice Nursing Quarterly. 1997; 3(1): 8–13.

- Eriksson K. Caring science in a new key. Nursing Science Quarterly. 2002; 15(1): 61–65.

- Eriksson K. Lindholm L. Lindström U. Matilainen D. Kasén A. Ethos anger siktet för vårdvetenskapen vid Åbo Akademi [Ethos gives the direction for caring science at Åbo Akademi University]. Hoitotiede (Nursing Science). 2006; 18(6): 296–298.

- Essén B. Johnsdotter S. Hovelius B. Gudmundsson S. Sjöberg N.-O. Friedman J, et al.. Qualitative study of pregnancy and childbirth experiences in Somalian women resident in Sweden. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2000; 107(12): 1507–1512.

- European Transcultural Nursing Association (ETNA). (2008). Retrieved August 11, 2008, from http://etna.middlesex.wikispaces.net/.

- Finfgeld-Connett D. Clarification of social support. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2005; 37(1): 4–9.

- Finfgeld-Connett D. Meta-synthesis of presence in nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2006; 55(6): 708–714.

- Finfgeld-Connett D. Meta-synthesis of caring in nursing. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2008; 17(2): 196–204.

- Granot M. Spitzer A. Aroian K. J. Ravid C. Tamir B. Noam R. Pregnancy and delivery practices and beliefs of Ethiopian immigrant women in Israel. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1996; 18(3): 299–313.

- Hanssen I. An intercultural nursing perspective on autonomy. Nursing Ethics. 2004; 11(1): 28–41.

- Herrel N. Olevitch L. DuBois D. Terry P. Thorp D. Kind E, et al.. Somali refugee women speak out about their needs for care during pregnancy and delivery. Journal of Midwifery and Women's Health. 2004; 49(4): 345–349.

- Hunter B. Berg M. Lundgren I. Ølafsdóttir Ó. Kirkham M. Relationships: The hidden threads in the tapestry of maternity care. Midwifery. 2008; 24(2): 132–137.

- Ito M. Sharts-Hopko N. Japanese women's experience of childbirth in the United States. Health Care for Women International. 2002; 23(6–7): 666–677.

- Jambunathan J. Stewart S. Hmong women in Wisconsin: What are their concerns in pregnancy and childbirth?. Birth. 1995; 22(4): 204–210.

- Jeppesen E. Tamer F. Tyrkiske invandrerkvinders erfaringer og holdninger i forbindelse med fødsel i Danmark [The experiences and attitudes of Turkish immigrant women in connection with delivery in Denmark]. Ugeskrift for Laeger (Weekly journal for medical doctors). 1988; 150(27): 1668–1671.

- Kennedy H. Rousseau A. Low L. K. An exploratory metasynthesis of midwifery practice in the United States. Midwifery. 2003; 19(3): 203–214.

- Leininger M. Culture care diversity and universality theory: Philosophic, epistemic, and other dimensions of the theory. Culture care diversity & universality: A theory of nursing. Leininger M. National League for Nursing Press. New York, 1991; 1–68.

- Leininger M. Culture care diversity and universality theory and evolution of the ethnonursing method. Culture care diversity and universality. A worldwide nursing theory2nd ed. Leininger M. McFarland M. Jones and Bartlett Publishers. Sudbury MA, 2006; 1–41.

- Liamputtong P. Watson L. The meanings and experiences of cesarean birth among Cambodian, Lao and Vietnamese Immigrant women in Australia. Women and Heath. 2006; 43(3): 63–82.

- Lindström U. Lindholm L. Zetterlund J. Katie Eriksson. Theory of caritative caring. Nursing theorists and their work6th ed. Marriner Tomey A. Alligood M. Mosby Elsevier. St. Louis MO, 2006; 191–223.

- Lundberg P. Gerezgiher A. Experiences from pregnancy and childbirth related to female genital mutilation among Eritrean immigrant women in Sweden. Midwifery. 2008; 24(2): 214–225.

- Maputle M. S. Jali M. N. Dealing with diversity: Incorporating cultural sensitivity into midwifery practice in the tertiary hospital of Capricorn district, Limpopo province. Curationis. 2006; 29(4): 61–69.

- McCourt C. Pearce A. Does continuity of carer matter to women from minority ethnic groups?. Midwifery. 2000; 16(2): 145–154.

- McLeish J. Maternity experiences of asylum seekers in England. British Journal of Midwifery. 2005; 13(12): 782–785.

- Meddings F. Haith-Cooper M. Culture and communication in ethically appropriate care. Nursing Ethics. 2008; 15(1): 52–61.

- Morgan M. Prenatal care of African American women in selected USA urban and rural cultural contexts. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 1996; 7(2): 3–9.

- Nabb, J. (2006). Pregnant asylum-seekers: Perceptions of maternity service provision. Royal College of Midwives-Evidence-Based Midwifery. , 4( 3), 89–95. Retrieved November 5, 2008, from http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_6862/is_3_4/ai_n28444698.

- National Advisory Board on Research Ethics. (2002). Good scientific practice and procedures for handling misconduct and fraud in science. Retrieved March 20, 2009, from http://www.pro.tsv.fi/tenk.

- Nelson A. A metasynthesis: Mothering other-than-normal-children. Qualitative Health Research. 2002; 12(4): 515–530.

- Nelson A. Transition to motherhood. Journal of Obstetric, Gynaecologic and Neonatal Nursing. 2003; 32(4): 465–477.

- Nelson A. A metasynthesis of qualitative breastfeeding studies. Journal of Midwifery and Women's Health. 2006; 51(2): 13–20.

- Noblit G. Hare R. D. Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies. Sage. Newbury Park CA, 1988

- Nøttveit A. Pregnant in an alien country. Vård i Norden [Nursing care in the Nordic countries]. 2000; 20(4): 46–51.

- Ny, P., Plantin, L., Karlsson, E., & Dykes, A.-K. (2007). Middle Eastern mothers in Sweden, their experiences of the maternal health service and their partner's involvement. Reproductive Health. , 24 (4), 9. Retrieved September 16, 2008, from http://www.reproductive-health-journal.com/content/4/1/9.

- Paterson B. Thorne S. Canam C. Jillings C. Meta-study of qualitative health research. A practical guide to meta-analysis and meta-synthesis. Sage. Thousand Oaks CA, 2001

- Pearce C. W. Seeking a healthy baby: Hispanic women's views of pregnancy and prenatal care. Clinical Excellence for Nurse Practitioners. 1998; 2(6): 352–361.

- Reid B. Taylor J. A feminist exploration of Traveller women's experiences of maternity care in the Republic of Ireland. Midwifery. 2007; 23(3): 248–259.

- Reitmanova S. Gustafson D. “They can't understand it”: Maternity health and care needs of immigrant Muslim women in St John's, Newfoundland. Maternal Child Health Journal. 2008; 12(1): 101–111.

- Rice P. L. What women say about their childbirth experiences: The case of Hmong women in Australia. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 1999; 17(3): 237–253.

- Rice P. L. Rooming-in and cultural practices: Choice or constraint?. Journal of Reproduction and Infant Psychology. 2000; 18(1): 21–32.

- Rice P. L. Naksook C. The experience of pregnancy, labour and birth of Thai women in Australia. Midwifery. 1998; 14(2): 74–84.

- Rice P. L. Naksook C. Watson L. The experiences of postpartum hospital stay and returning home among Thai mothers in Australia. Midwifery. 1999; 15(1): 47–57.

- Sandelowski M. Barroso J. The travesty of choosing after positive prenatal diagnoses. Journal of Obstetric, Gynaecologic and Neonatal Nursing. 2005; 34(3): 307–318.

- Sandelowski M. Barroso J. Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. Springer. New York, 2007

- Sandelowski M. Docherty S. Emden C. Qualitative metasynthesis: Issues and techniques. Research in Nursing and Health. 1997; 20(4): 365–371.

- Sharts-Hopko N. Birth in the Japanese context. Journal of Obstetric, Gynaecologic and Neonatal Nursing. 1995; 24(4): 343–351.

- Sherwood G. Meta-synthesis of qualitative analyses of caring: Defining a therapeutic model of nursing. Advanced Practice Nursing Quarterly. 1997; 3(1): 32–42.

- Small R. Rice P. L. Yelland J. Lumley J. Mothers in a new country: The role of culture and communication in Vietnamese, Turkish and Filipino women's experiences of giving birth in Australia. Women and Health. 1999; 28(3): 77–101.

- Tandon S. D. Parillo K. Keefer M. Hispanic women's perceptions of patient-centeredness during prenatal care: A mixed method study. Birth. 2005; 32(4): 312–317.

- Templeton L. Velleman R. Persaud A. Milner P. The experiences of postnatal depression in women from black and minority ethnic communities in Wiltshire, UK. Ethnicity and Health. 2003; 8(3): 207–221.

- Transcultural C.A.R.E. Associates. (2008). Retrieved August 11, 2008, from http://www.transculturalcare.net/.

- Transcultural Nursing. (2008). Cultural Diversity in Nursing. Retrieved August 11, 2008, from http://www.culturediversity.org/.

- Transcultural Nursing Society. (2008). Retrieved August 11, 2008, from http://www.tcns.org/.

- Tsianakias V. Liamputtong P. What women from an Islamic background in Australia say about care in pregnancy and prenatal testing. Midwifery. 2002; 18(1): 25–34.

- Vangen S. Johansen R. E. Sundby J. Traeen B. Stray-Pedersen B. Qualitative study of perinatal care experiences among Somali women and local health care professionals in Norway. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2004; 112(1): 29–35.

- Wheatley R. Kelley M. Peacock N. Delgado J. Women's narratives of quality in prenatal care: A multicultural perspective. Qualitative Health Research. 2008; 18(11): 1586–1598.

- Wikberg A. Eriksson K. Intercultural caring – an abductive model. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science. 2008a; 22(3): 485–496.

- Wikberg, A., & Eriksson, K. (2008b). Vårdande mellan olika kulturer [Caring between different cultures]. In D. Matilainen, K. Eriksson, & U. Lindström. Vårdvetenskap i hälsans och vårdandets tjänst. [Caring science in the service of health and caring]. X nationella vårdvetenskapliga konferensen [X national nursing science conference] (pp. 183–191.). 26–27 September. Vaasa: Åbo Akademi University.

- Wiklund H. Aden A. Högberg U. Wikman M. Dahlgren L. Somalis giving birth in Sweden: A challenge to culture and gender specific values and behaviours. Midwifery. 2000; 16(2): 105–115.

- Woollett A. Dosanjh-Matwala N. Postnatal care: The attitudes and experiences of Asian women in east London. Midwifery. 1990a; 6(4): 178–184.

- Woollett A. Dosanjh-Matwala N. Pregnancy and antenatal care: The attitudes and experiences of Asian women. Child: Care, Health and Development. 1990b; 16(1): 63–78.

- Yelland J. Small R. Lumley J. Rice P. L. Cotronei V. Warren R. Support, sensitivity, satisfaction: Filipino, Turkish and Vietnamese women's experiences of postnatal hospital stay. Midwifery. 1998; 14(3): 144–154.

- Yeo S. Fetters M. Maeda Y. Japanese couples’ childbirth experiences in Michigan: Implications for care. Birth. 2000; 27(3): 191–198.