Abstract

The aim of this qualitative study is to explore the way people using modern health care perceive its consequences in Ouraman-e-Takht region of Iranian Kurdistan. Ouraman-e-Takht is a rural, highly mountainous and dry region located in the southwest Kurdistan province of Iran. Recently, modern health practices have been introduced to the region. The purpose of this study was to investigate, from the Ouramains’ point of view, the impact that modern health services and practices have had on the Ouraman traditional way of life. Interview data from respondents were analyzed by using grounded theory. Promoting survival was the core category that explained the impact that modern health practices have had on the Ouraman region. The people of Ouraman interpreted modern health practices as increasing their quality of life and promoting their survival. Results are organized around this core category in a paradigm model consisting of conditions, interactions, and consequences. This model can be used to understand the impact of change from the introduction of modern health on a traditional society.

Introduction

Iranian Kurdistan is experiencing a great deal of social change. Among the most important changes are the expansion of modern health practices into rural communities, the emergence of a new economic structure with greater job opportunities, and an increasing degree of modern education. However, there is little research that documents the impact that such changes have on the way of life of local residents. Over the years, many studies by both the outsiders and the insiders have attempted to explain the various aspects of Kurdish society and culture. Most of these studies mainly concentrated on political, racial, and ethnic issues, conducted employing historical and documentary methods of data collection, and presented as tales and narratives (Kurdistani, Citation1972). In addition, most of the studies conducted by outsiders were based on historical and archival data rather than fieldwork or qualitative methodology (Kochera, Citation1994; Nikitin, Citation1999). Thus, many aspects of modern-day Kurdish society remain unexplored and unexplained. Studies using qualitative methods and ethnographic fieldwork are needed to understand the impact of modern changes and developments on the people who live through, and experience them.

The purpose of this article is two-fold: first, to explain from the Ouraman point of view the impact that modern health practices are having on Kurdish society; second, to present a data-based theoretical framework that can be used to understand and study changes in similar societies.

Review of related literature

Research studies conducted on the Kurds can be classified into two ways, those done by researchers of Kurdish or Iranian origin, the so-called internal researchers, and those done by external researchers from outside of Iran. Most of the internal studies have focused on political, historical, and religious issues. Among the most important studies were those done by Borzoei (Citation1999), Mohammadpur (Citation2001 Citation2005 Citation2007), Safinezadeh (Citation1994), and Yasemi (Citation1995). Of the internal studies only those conducted by Mohammadpur (Citation2001 Citation2005 Citation2007) and Rezaei (Citation2002) were qualitative methods and they focused mainly on socio-economic and cultural issues. The external studies were conducted by European researchers, primarily French (Kochera, Citation1994; Nikitin, Citation1999). Some of the field reports and monographs were based on data gathered during short-term visits to Kurdistan (Randall, Citation2002). However, most of the studies did not employ fieldwork at all, but were based on secondary/documentary data, which existed in the political archives of the governmental agencies. These data were gathered by governmental agencies when representatives of the countries were intervening in internal affairs of Kurdistan or when the countries were in Kurdistan following their own political and economic interests in Middle East. Most important among the external studies are those conducted by Edmond (Citation1989), Kendal, Sharif, and Nazdar (Citation1991), Linan (Citation1993), McDowell (Citation1991 Citation2002), Olson (Citation2001), and Van Bruinessen (Citation1999). The most relevant and specific of these were those conducted by McDowell (Citation2002), and Nikitin (Citation1999), and Van Bruinessen (Citation1999).

Background

The rise of health services in Kurdistan began in 1921 as a part of an overall plan to modernize Iran directed by governmental institutions. From that time to the present, the health system has been developing both quantitatively and qualitatively. Presently, there are a large number of health clinics, health houses, and similar agencies in both rural and urban regions of Iranian Kurdistan. Among the important consequences of this proliferation are an increase in quality of life, public safety, and health especially among women and a decrease in child mortality, epidemic diseases, and in the health services gap between rural and urban areas. Nowadays, hospitals, a few health service centers and other health institutions are established in both urban and rural settings. There is no doubt that the health development has had a significant determining effect on personal and economic development in contemporary Iranian Kurdistan (Mohammadpur, Citation2001 Citation2005 Citation2007; Mohammadpur, Sadeghi, Rezaei, and Partovi, Citation2009).

This introduction of health services was accelerated especially during the post-revolutionary period from 1979 until the present. In the first decade of post-revolutionary period, the Organization of Jihad Sazandagi was charged with providing health services and facilities, such as rural baths, health houses, and rural physicians. As a result of their efforts, elementary rural health houses were built in each village and one or more Behvarzes (i.e., a rehabilitator who provides some health services but is not a nurse) and physicians were assigned to the health houses depending upon the village population, number of children, and the general level of health or diseases. But, in some rural areas a main health house (called Mother Health House) was built so that the peoples of adjacent villages would have access to it. In addition to governmental efforts, the indigenous people also participated extensively in the construction of health houses by providing manual labor, donating land for health house buildings, and whenever possible, helping out financially. According to official records of the Ouraman region there are now 13 health houses and 21 Behvarzes. These can be taken as an evidence of the quantitative development of modern health services in the region.

In rural areas of Iranian Kurdistan, most of the people were able to obtain health services through health houses established in their villages. However, there are still some obstacles to access the modern health services in rural areas, so people have to leave the area to obtain health services in urban areas. The first of these obstacles is that many rural health houses are not much equipped with facilities and services; they mostly offer elementary health care. For more advanced health services, the people have to travel to urban regions. In addition, most of Behvarzes and social workers employed have little health care training or experience.

The situation is different in rural areas that are in closer proximity to cities. The people can go to urban health centers or hospitals easier than those in remote villages. All in all, today a large number of Kurdish people are taking advantage of modern health services and facilities. One of the positive consequences of this is that many educated persons return to take health care or hospital jobs in their cities or villages of origin. Presently, most of the Behvarzes and hospital staff in Iranian Kurdistan are Kurdish while only a decade ago, most of the hospital and health centers personnel working in Kurdistan were Iranians from the outside the area of Kurdistan.

Despite governmental attempts to raise health levels by building health centers and health houses in rural areas, there is a significant amount of the population in Kurdistan that remains without access to advanced health care, and there are several regions where there are insufficient or inadequate health houses, Behvarzes, or social workers. For these reasons, there remains a health gap between the rural and urban population and social inequalities in health services.

Setting

This research was conducted in the Ouramanat-e-Takht region of Iranian Kurdistan. Ouramanat refers to a highly mountainous and dry region located in western Iranian Kurdistan along the Valley of Sirwan River. Along the river basin, there are about 13 small villages. The inhabitants of this region are called Ouramy, which is also the name of one of the four Kurdish dialects. This area is divided into three sub-regions including Ouraman-e-Takht; Ouraman-e-Lahon; and Ouraman-e-Javaro. Among them, the Ouramanat-e-Takht has been the site of many sacred and religious beliefs and legends. Among the villages, Ouraman is the largest one, and well known. It serves as the official and governmental center of the region. It is also considered as an ancient and sacred religious site.

Since the data for this study were gathered during the summer, a large number of people were living in their respective summer villages. Despite living in very difficult conditions in these villages, the Ouramian people live in healthy cottages built from stones. Although small, all cottages had a WC, bathroom, and kitchen. Though the place is interesting from a cultural and sociological point of view, it can be a hard place to live: the heat is exhausting and the mountainous terrain swarms with mosquitoes and flies. It takes an outsider a considerable amount of time to adapt to the climate and the terrain. Ranching and gardening constitute the main economic activities during the summer period. Another aspect of the region is that a large number of youth work outside of Ouraman as laborers in Tehran or other Kurdish cities. Some of youth eventually return to their city of origin taking advantage of new opportunities for employment, such as working as shopkeepers, drivers, teachers, clerical workers, and as health service workers and in clinics. Furthermore, the introduction of electricity, telephone, gas, and video–audio technologies have presented other employment opportunities and given the Ouramy new work options.

Methodology

The aim of this research was to explore the consequences of social change on the traditional way of life of the Ouraman people from their perspective. This research employed a grounded theory approach for data collection and analysis. Grounded theory was developed originally by Glaser and Strauss (Citation1967) and later expanded by Charmaz (Citation2006), Corbin and Strauss (Citation2008), and Strauss and Corbin (Citation1998). Grounded theory was chosen because it allows the researcher to study the impact of change from the perspective of those experiencing that change. It also enables researchers to develop data-based theoretical frameworks to understand and explain the change. Grounded theory is especially useful for studying topic areas that are difficult to access using orthodox (i.e., positivistic) methods (Glaser, Citation1998; Glaser & Strauss Citation1967).

The essence of grounded theory is the inductive examination of textual information. In a grounded theory approach, a researcher simultaneously collects, codes, and analyzes the data. The decision of what and where to collect the next set of data is guided by the developing theory. Although the initial decision is based on a general problem area, subsequent groups of participants are chosen for their theoretical relevance to the development of categories (Charmaz, Citation2006; Corbin & Strauss, Citation2008; Glaser, Citation1978; Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967).

Data collection

Based on the famous dictum of Glaser (Citation2002), “all is data,” the grounded theory researchers may use many forms of data including observations, interviews, and documents, all of which could contribute in generating substantive theory. In this study in Ouraman, data were collected by using the ethnographic fieldwork method. We conducted the fieldwork over 2 months and returned periodically. It took us more than 5 h to travel to the first village of the region and from there another 9 h to travel to the last village distanced. We had established initial friendly relationships with the villagers during an exploratory study so we were familiar with those influential persons, such as religious authorities, elders, teachers, and other peoples in the region, and they embraced us in many ways. Based on purposive sampling in initial stage of data collection and later snowball sampling, we interviewed 36 informants from 13 villages about health services, their introduction and consequences. The main question posed to participants was: “How do you think modern health began in your society and what you perceive are its major benefits and detriments to society and the Kurdish way of life?” Other questions followed based on findings derived from the initial interviews and the evolving conceptual framework.

Interviews were conducted until redundancy was reached. Interviews were transcribed to best represent the dynamic nature of the living conversation. For further empathy and trust, we used videotape to record interviews; in all cases, the verbal permission was obtained as an ethical consideration. Each of the verbatim transcripts was returned to the participant for his/her review so he/she could remark on the accuracy of the document. During the research, each participant was assured confidentiality through the use of pseudonyms in the reporting of data. They were also assured that once the data were coded, connections back to individual participants are almost impossible to trace. Identification of the individual participant is not paramount because the concepts generated by the participants—not the individual participants—are at the center of study (Glaser, Citation1978). In addition to interviews, participant observation was used. We observed the health services, health houses, and the medical practices and facilities they contained. Also, we scrutinized the everyday life of Ouramian peoples to discover their health behaviors and beliefs. Observational notes included descriptive, personal, and analytic notes on the domains observed. Then, these notes were classified and used to support and supplement the analytical stage of study.

Participants

The study comprised of 36 participants of various backgrounds. The main criterion for study participation was engagement in the everyday life in community. Any individual who met this condition was considered a possible participant. Purposive sampling was used to locate first informants and then snowball/chain sampling was taken to find other relevant and information-rich cases. The age range of participants was 21–68 years with most persons being in the 37–54 range; there were 20 men and 16 women. Except for a few (mostly women), most of them had some education, ranging from elementary levels to academic degrees.

According to Strauss and Corbin (Citation1998), grounded theory requires that sampling is theory driven and as such developed in the field as the theory emerges. In the process of initial interviewing, there emerged several interesting and relevant concepts, such as embracing modern health care, increasing quality of life, eradicating diseases, and so on which theoretically guided discussions and interviews. The interviewing process ended as soon as the theoretical saturation of main questions was attained.

Data analysis

Data were collected and analyzed simultaneously, according to the grounded theory approach. Grounded theory is a constant comparative methodology that combines data analysis with data collection. The heart of data analysis in grounded theory is based on three types of coding procedures: open, axial, and selective. During open coding, transcripts of each interview were reviewed multiple times and the data conceptualized and reduced to codes. In this first level of open coding, 42 concepts were extracted. Codes found to be conceptually similar in nature or related in meaning were grouped to form categories or the main themes of the study. In this stage, called focused coding, seven main categories emerged which constituted the major components of our grounded theory analysis.

Axial coding was used then to develop categories/themes. This process allowed links to be made between categories and their sub-categories. Once the core category was chosen using the criteria for the core category as described in Strauss and Corbin (Citation1998), selective coding was used to integrate categories into a theoretical scheme and to fill in any category that remained underdeveloped. Subsequently, based on the core category and using the paradigm features of Strauss and Corbin (Citation1998) a conceptual explanatory model was constructed to depict the relationship between concepts and the core category.

According to Glaser and Strauss (Citation1967), and Corbin and Strauss (Citation2008), the core category should be abstract, comprehensive, analytical, and frequently cited in collected data. Therefore, the core category selected was Promoting Survival, which captures and includes all main categories extracted.

Results

The theoretical formulation constructed from data to explain the impact of modern health practices on the Ouraman region of Iranian Kurdistan is entitled Promoting Survival. This concept integrates all of the other concepts and main categories, and explains the perspectives of the Ouraman people about the benefits or advantages of modern health practices in comparison to their traditional health system. The changes to society brought about by modern health services have the potential to reduce and even eradicate many traditional and epidemic diseases and illness. The interesting point is that while the participants in this study (especially the less-educated people—mostly elders) welcomed the creation of new health houses and health services, and the possibility of improving their own and families’ health, they also saw the advantages of traditional health care that has endured and prospered for hundreds of years.

While valuing traditional health care, the Ouramian people have embraced modern health practices that help them to recover from illness, eradicate epidemic diseases, increase quality of life, increase life expectancy, promote the general health and welfare of families, and decrease mortality. These benefits are viewed as the real and potential advantages of the modern health services. The challenge of the Ouramny is to create an atmosphere where both the modernization and the tradition can co-exist, a situation where they can take advantage of the benefits that modern health services bring without losing what was good about their past health practices.

In addition to the core category, seven other main categories were derived from the data. These include: Suffering epidemic diseases, Introducing modern education, Facilitating inter-regional communications, Supplementing traditional care, Public use, Embracement, and Vital benefits.

Each main category is explained briefly in following sections and documented with one or two quotations by participants.

Suffering epidemic diseases

The Ouramian peoples have suffered chronically from epidemic diseases in the past. They narrated many tales about catastrophic diseases and infectious illnesses that spread throughout their villages and killed large numbers of people, especially infants and children. In spite of traditional health practices, experienced elders, and natural medicines, patients rarely recovered and there was little that could rescue the population from these diseases. As a result, the introduction of modern health services was considered as a means of rescuing people from this horrible situation. One of the informants stated:

For example, in this village [pointing to the village in which he resided], there existed many killing diseases, such as smallpox and cholera, which became epidemic in the village. A large number of people were annihilated every year. An infectious disease suddenly came to appear, and took the life of a large number of inhabitants; nobody could resist. Now, you see that the modern health possibilities eradicate, if not all, most diseases. The people no longer are at risk of dying compared to the past. (Excerpt from field notes)

Our past life was not similar to current one … I remember that about half of the people died; it is believed that they are killed by bad spirits, by evils; more than half of the religious authorities lived by writing sacred notes! They wrote more than a few religious words on a piece of paper and gave to patients as a medicine, for healing them … while most of them died from poisonous illnesses, or from unknown diseases. Some elders or experienced persons prescribed this or that herb, but it was mainly by chance; now, since the modern health entered our region, the bad spirits and demons escaped!! Now, the people do not die so easily. (Excerpt from field notes)

Introducing modern education

The participants strongly emphasized that introducing modern education increased their knowledge about their surroundings, events, and health issues. They now are able to know and understand happenings in their lives and the environment. They know how to better handle personal issues and concerns, and can make more informed decisions. One of the participants explains:

As far as I know, the people in the past when they got sick, acted upon instructions suggested by religious authorities or experienced elders. Now, you can see that most of the people are educated, all children go to school, youths go to universities; they are taught about everything you imagine. They learn about health and healthy matters. This modern education provided us with health knowledge and skills. Today, people have learned how to protect themselves against diseases. (Excerpt from field notes)

There are a few people who oppose Behvarzes and their health advice, the medicines, or doctors. That is, most of people accepted the new health care as they are educated and know what it is going in the current world. Even if they could not recognize it, their children do! (Excerpt from field notes)

Facilitating inter-regional communications

Over a few last years, communication with the outside world has been improved through the introduction of vehicles, roads, telephones, and mass media. All of these are frequently used by Ourmians and they have facilitated inter-regional exchanges and paved a way for inhabitants to become more familiar with modern health services, healthy lifestyles, and new health practices. For example, television (TV) and satellite TV contributed to enhancing people's health knowledge and experiences. Vehicles and roads provided easy access to urban regions where they learn more about health issues. One of the informants expressed:

Nowadays the situation is different than the past when only elders were experienced and wise, and only they could advise people about healthy and unhealthy issues. Now, each child knows that! They watch TV and satellite to the extent that they learn many things. In our village, all of us have satellite; it is a very good apparatus showing various programs such as health information, and it looks like a school, teaching many things needed for today life. (Excerpt from field notes)

We go to nearby or remote cities such as Marivan, Snanadaj, Tehran … we get familiar with new life styles, we learn what benefits us, what things are healthy, how should we manage our lives to be safe and healthy; we learn about medicines, doctors, and treatment. So, it is clear that nobody relies on elders’ advice when he/she is sick. Visiting Behvarzes is preferred, if not recovering; he/she goes to doctor. (Excerpt from field notes)

Embracement

The participants point to modern health as something that has brought with it many positive possibilities and has contributed to their progress. In this regard, one of the participants stated:

We welcome new health because it is good for us, most of people love it. Love to be safe, love to be healthy. We would like to develop new health as far as possible. Now health determines many things such as quality of life, personal knowledge and sensitivity, and many other things. (Excerpt from field notes)

Yes, of course, who does not like the new health facilities? It is our wish to be more and more expanded. When I look at the past, I understand how much it is worth. It is God's gift. (Excerpt from field notes)

Public use

Taking advantage of modern health services, such as local health houses, clinic centers, and medical possibilities, is quite common in the region. Most of the people relied on new medical services when they get sick. For example, women are visited by midwives during their pregnancy or for other diseases and families are requested to bring their children to check their health status several times in the year. Therefore, all Behvarzes, midwives, and doctors were engaged in offering medical services as a part of everyday life. One of the participants asserted:

Our health houses are too busy from morning to night, or midnight. They visit our children, our women; they offer some guidance very helpful for our life; it is impossible to live without their assistance nowadays. (Excerpt from field notes)

Sometimes, the health house is overloaded; to get access to some medicines, we go to the center village of Ouraman where a central health house and drug store exists. If it does not work, we go to nearby urban regions. (Excerpt from field notes)

Supplementing traditional care

Though the Ouramians see the need for and embrace health, there exists at the same time some concerns and anxieties about how to preserve many traditional ways of healing and treatment. There exist a large number of sacred places highly respected by the people. It is believed that these places serve for healing those who have serious diseases and mental problems, such as spiritual disease, psychological anxiety, and infertility of women. What is most interesting from an analytic point of view is that people want it both ways. They want modern health services and yet to maintain tradition at the same time because the people believe that the traditional/religious ways could supplement the modern health devices. In reference to this, one of the participants said:

In our region, the physicians are as respected as praying to God, and many traditional ways, each one has its own place … humans should never forget God's will and ability; there is no opposition between them. In the meantime, all things in the world are God's creatures, the medicine, doctor, and other things. (Excerpt from field notes)

God's will is highest, it is beyond all humans’ power, but the medicine, physicians, and these things are God's instruments; it is a sin if the human does not use them, these are created for human beings. (Excerpt from field notes)

Vital benefits

The Ouramians considered modern health services as something vital for their life. It has provided possibilities that empowered people of the region to survive. It is believed that modern health facilities has brought about decreasing mortality, family planning programs, improvement of quality of life, personal and social healthiness, and so on. Regarding this, an informant stated:

Today, as the health services have promoted, God Blessing, the people are healthier both mentally and physically. It was said that once upon a time, about 30 persons died in the region in one day only. Nobody could help at all; no solution. But currently, due to modern medical possibilities, no similar event has come up. (Excerpt from field notes)

I think that this modern health or medical possibilities means rescuing peoples from death! Well, how could I explain the thing that saves human from death! In the past, we had lice and fleas, so, we had to shake our clothes on the fire to clean them. People now are very healthy; before, each family had more than 7–8 children. All of them were dirty; you see now that each family has a few fresh and clean children as they know how they should manage their lives. I cannot express what I feel, I think that what the visiting doctor charges could never be paid, it is too cheap compared to its vital benefits. (Excerpt from field notes)

Theoretical model — diskussion

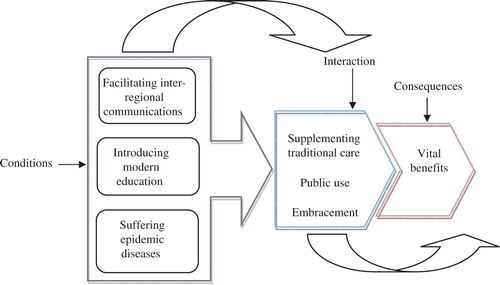

The following theoretical model of Promoting Survival has been constructed to help explain the impact of modern health or the introduction of change into a traditional society.

The paradigm model of Promoting Survival consists of three parts (). These include: conditions, interactions, and consequences. The first part of the model deals with conditions leading to the emergence of modern health in Ouraman; these conditions include: Suffering epidemic diseases, Introducing modern education, and Facilitating inter-regional communications. These conditions prepared the way for modern health services to enter the region. Ouramian people welcomed these services to solve their health-related problems and to improve their quality of life. Modern health services provided them with an opportunity to overcome on the diseases and the sufferings associated with unhealthy or less-healthy conditions. Another condition paving the way for health was that persons acquired the knowledge and modern education necessary to live in a modern world, a quite different from the traditional world they had so long lived in. Modern education made people aware of events, issues, and circumstances around the globe, and also offered them knowledge to deal with modern social life, learning how and when to use modern health facilities and services. Also, the interregional communications increased the geographical mobility, to cross the traditional borders, travel out of region, and learn new life styles and technologies. In regards to these issues, the Ouramian people found modern health services as a functional instrument enabling them to cope with the modern and traditional diseases and unhealthy situations they now are faced with.

Figure 1. The grounded theory model of the meaning reconstruction of modern health consequences as promoting survival.

The model also demonstrates that certain action/interactions occurred in the region when modern health was introduced. As soon as modern health services appeared, they were largely and publicly welcomed, embraced, and used. Seeing their potential benefits convinced the Ouramians people to embrace and take advantage of health facilities and services, and to respect the Behvarzes and local physicians. And yet, while seeing the need for modern health there is also the sense of the supplementary traditional and belief-based medical devices. In this respect, the people see no contradiction between modern and traditional medical services. The challenge becomes preserving what was good about the medical ways in the past while embracing what is necessary of the modern to move the society forward and ensure its continuance.

The final part of the model portrays the consequence of the introduction of modern health in Ouraman. The consequence has been categorized as vital benefit. The emergence and acceptance of modern health yielded vital development and enhanced the quality of life.

Conclusion

The introduction of modern health into the traditional Ouraman society has brought about many changes enabling the people of the region to overcome some of the suffering that comes from their inability to cope with unhealthy conditions and epidemic disease, and to enrich their lives by giving them some control and power over their own lives. While embracing the changes that modern health services have brought, the Ouramian people are concerned about how to hold onto their traditional ways of healing and medical possibilities that have for so many years defined their society and given it meaning. In many ways the Ouramians want to combine the new and old health devices. Modern health is accepted as a result of some conditions (Facilitating inter-regional communications, Introducing modern education, and Suffering epidemic diseases) and it creates a situation for social change that in turn leads to positive consequences. The challenge is to keep a balance between the old and the new, so that the society can flourish yet keep its sense of identity. These findings have implications for all developing countries that are undergoing the same situation that is occurring in Iranian Kurdistan, where two seemingly contradictory states-modernity and tradition-exist side by side and where it is important for one to flourish without destroying what was good about the other. The model of Promoting Survival developed from this study can help other societies undergoing similar situations to understand what happens when modern change is introduced into a traditional society and to enable people and government to develop solutions that allow the changes to take root while constraining the loss of tradition.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry to conduct this study.

Acknowledgements

We warmly appreciate Professor Debra Skinner at UNC-Chapel Hill, NC, USA for her kind helps in editing the final version of this article.

References

- Borzoei, M. (1999). Political problems of Kurdistan. TehranIran: Fekre Noe. ( In Persian)

- Charmaz K. Grounding grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage. London, 2006

- Corbin J. Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research3rd ed. Sage. London, 2008

- Edmond, S. (1989). Kurds, Turks and Arabs (E. Yonesi, Trans. into Persian). TehranIran: Rozbehan.

- Glaser B. Theoretical sensitivity. Sociology Press. Mill Valley CA, 1978

- Glaser B. Doing grounded theory: Issues and discussions. Sociology Press. Mill Valley CA, 1998

- Glaser B. Strauss G. Discovery of grounded theory. Transaction Publishers. Mill Valley CA, 1967

- Glaser, B. G. (2002). Constructivist grounded theory?. Qualitative Social Research. , 3 (3), Article 12. Retrieved November 19 2009, from http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/3-02/3-02glaser-e.htm.

- Kendal, N., Sharif, E., & Nazdar, M, et al.. (1991). Kurds (E. Yonesi, Trans. into Persian). TehranIran: Rozbehan.

- Kochera, C. (1994). National movement of Kurds (E. Yonesi, Trans. into Persian). TehranIran: Negah.

- Kurdistani, M. (1972). History of Kurd and Kurdistan and its districts. SanandagIran: Garighy. ( In Persian)

- Linan, D. (1993). Kurd and Kurdistan. ( E. Younesi, Trans. into Persian). TehranIran: Negah.

- McDowell D. The Kurds: An historical perspective. Asian Affairs. 1991; 22(3(3)): 293–303.

- McDowell, D. (2002). The modern history of Kurds (E. Yonesi, Trans. into Persian). TehranIran: Paniz.

- Mohammadpur, A. (2001). The process and consequences of modernization in Iranian Kurdistan from 1921–2000: Case study of Sardasht township. ( M.A. Thesis). Shiraz University., ShirazIran.

- Mohammadpur, A. (2005). Culture, education and development in contemporary Iranian Kurdistan. Fourth Annual of Education and Culture Forum, Italy.

- Mohammadpur, A. (2007). The meaning reconstruction of modernization consequences in ouramanat region of Iranian Kurdistan: A grounded theory study. ( Ph.D. Dissertation), Shiraz University., ShirazIran.

- Mohammadpur, A., Sadeghi, R., Rezaci, M., & Partovi, L, et al.. (2009). A mixed method study of family changes among Mangor and Gaverk Tribes of Mahabad township. Journal of Women Research. , 7 (4), 71–93. (In Persian).

- Nikitin, V. (1999). Kurds and Kurdistan. ( M. Qazi, Trans. into Persian). TehranIran: Derayat.

- Olson, R. (2001). Problem of Kurd. ( E. Younesi, Trans. into Persian) ( 1380). TehranIran: Paniz.

- Randall, J. (2002). With this knowledge what is forgiveness? (E. Yonesi, Trans. into Persian). TehranIran: Paniz.

- Rezaei, M. (2002). A study of population and human development situation in Iranian Kurdistan. ( M.A. Thesis). Shiraz University., ShirazIran.

- Safnezadeh S. History of Kurd and Kurdistan. Atie. TehranIran, 1994

- Strauss A. Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques2nd ed. Sage. Thousand Oaks CA, 1998

- Van Bruinessen M. Agaha, Sheikh, State (E. Yonesi, Trans. into Persian). Paniz. TehranIran, 1999

- Yasemi, R. (1995). Kurds and their racial and historical belonging. TehranIran: Amir Kabir. ( In Persian)