Abstract

The aim of this qualitative study was to deepen the knowledge of how individuals with schizophrenia themselves describe what they need in order to increase their well-being in everyday life. Seven patients were interviewed. An open explorative approach was applied and grounded theory was used for the analysis resulting in five categories illustrating how patients with schizophrenia handle their struggle for a normal life. The patients stressed first the importance of receiving information about the disease: for themselves, for society, and for their families. Taking part in social contacts such as attending meeting places and receiving home visits were identified as important as well as having meaningful employment. They also pointed out the importance of taking part in secure professional relationships. Mainly they expressed the need for continuity in the relationships and the wish to be heard and seen by the professionals. Finally, interviewees addressed the need for support for sustaining independent living through practical housekeeping and financial help. To conclude, the participants in the present study described their need for help as mainly linked to activities in their overall life situation rather than just their psychosis.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is one of the world's most devastating psychiatric disorders and causes suffering for millions of people and their families worldwide. Lifetime prevalence is estimated to 1% and the first symptoms usually appear when the individuals are in their late teens. Approximately 20% of patients have complete symptoms relief from medication (Flyckt, Citation2008). About 60–70% of the patients gain some relief but with remaining symptoms throughout life (Topor, Citation2001), and 20–30% do not gain any relief from medications at all (Flyckt, Citation2008). Between 10 and 15% of the patients commit suicide (Meltzer, Citation2002) and only a minority of the patients are able to work and to start a family of their own. There are differences between men and women who develop psychosis. Men typically have an earlier onset, have worse pre-morbid functioning, a higher degree of negative symptoms, lower degree of affective elements, and a poorer prognosis than women (Häfner et al., Citation2003; Lindamer et al., Citation2003; Preston, Orr, Date, Nolan, & Castle, 2002; Salokangas, Honkonen, & Saarinen, 2003;Usall, Ochoa, Araya, & Marquez, 2003). Women's higher pre-menopausal estrogen levels have been suggested as a possible explanation of these differences (Häfner, Hambrecht, Loffler, Munk-Jorgensen, & Riecher-Rossler, 1998).

There are relative few articles addressing the subjective assessment of assistance needs of persons with mental illness (Arvidsson, Citation2001; Foldemo, Ek, & Bogren, 2004, Hansson et al., Citation2001 Citation2003; Slade, Phelan, & Thornicroft, 1998; Slade, Phelan, Thornicroft, & Parkman, 1996). Data for many of these articles originated in structured interviews with multiple choice answers such as the Camberwell Assessment of Need (CAN). The CAN assesses patients’ needs in 22 different areas including housing and basic education (Slade et al., Citation1996). However, there may be significant differences between patients’ with schizophrenia and their staff's CAN estimates (Slade et al., Citation1996 Citation1998). Staff usually saw needs in areas related to the disease such as symptoms, while the patients emphasized needs related to their life situation such as needs for information about treatment, welfare, and opportunities to express their sexuality. The staff were more likely than the patients to feel that patient needs had been satisfied. Hansson et al. (Citation2001) found that both patients and staff judged social relationships to be the area in most need of help. However, the patients additionally identified the lack of intimate relationships and wanted assistance in dealing with psychological suffering, while the staff saw a significant need for help dealing with the psychotic symptoms and daily activities. Staff estimates of need were positively correlated with the severity of the patient's mental illness. In contrast, the patients’ assessment correlated negatively to the level of life quality; that is, individuals with low life quality rated themselves in need of greater help. Conversely, Arvidsson (Citation2001) found that staff estimated patient needs as less met than did patients themselves. However, patients and staff could agree on which areas most required help: psychotic symptoms, psychological suffering, home life, and social relationships. Foldemo et al. (Citation2004) also studied what the patients’ parents estimated as needed in addition to schizophrenia patients and staff. Although both staff and parents estimated an equal level of required help, they differed in which area help was needed. Whereas parents perceived financial and physical health assistance as most lacking, staff saw the need for accommodation apply and home living skills.

Another study examined the possible association between needs as estimated by CAN and perceived quality of life using the Lancashire Quality of Life Profile (Hansson et al., Citation2003). They found a significant association between the patient's unfulfilled needs and a low-rated quality of life. The greatest impact on quality of life was found to be unsatisfied needs concerning social relations.

Overall, these studies indicate that staff sees the need for help lie mainly in the medical field, while both parents and patients saw the need for help in various aspects of daily life. Several researchers point out that the importance of considering not only health professionals estimations of patients’ need for help (Arvidsson, Citation2001; Hansson et al., Citation2001; Slade et al., Citation1996 Citation1998), but parents (Foldemo et al., Citation2004) as well since both may differ significantly from the patient's own assessment. Particular attention should be paid to the unfulfilled needs that the patients themselves identified, as these seem to have a negative impact on patients’ perception of life quality (Hansson et al., Citation2001 Citation2003). The concept of well-being is closely related to quality of life and can be defined as to what extent the individual's physical, psychological, and spiritual needs are met. The definition of Renwick and Brown (Citation1996) has been an inspiration in the present study. It states that quality of life is connected to the degree to which a person enjoys possibilities in life in the area of Being—reflecting “who one is”; Belonging—reflecting the person′s belongingness and connection to the social environment; and Becoming—reflecting the possibility to reach personal goals, hopes, and aspirations.

While the use of a structured interview guide such as CAN to investigate psychiatric patients’ need for help may capture a variety of areas requiring attention, the use of pre-defined areas risks limiting the scope of what should be investigated since the patient's spontaneous response to perceived needs and the nuances surrounding the person's subjective preferences are lost. Therefore, this qualitative study aims to examine schizophrenia patients’ perceived needs in an explorative manner. To our knowledge there are no explorative qualitative studies addressing how individuals with schizophrenia describe what they need in order to increase their well-being in everyday life. The aim was, therefore, to deepen the knowledge within this area. The study seeks to answer the question: What help do people with schizophrenia perceive as important in order to increase their well-being?

Method

Participants

Patients were recruited at an outpatient ward for individuals with psychosis. An informational letter about the study was put in the reception room, and the reception staff also gave letters to those they thought might be interested in participating in the study. The inclusion criterion was a medical history of psychosis with preference to schizophrenia. Especially requested were respondents with long experience in various support and care efforts so that they had many experiences to relate to. No specific exclusion criteria were used. Out of the nine who registered interest, two declined participation; consequently, interviews were conducted with seven respondents, six women and one man aged between 33 and 66 years. All interviewees had their first psychotic diagnosis between 10 and 37 years ago, and all but one have been diagnosed with schizophrenia according to DSM-IV (APA, 1994).

Data collection

In accordance with the explorative approach, interviews were open and focused on the question: “What is important for you to get help with?” Follow-up questions were adapted to the interviewee's answers. Each interview began with the interviewer giving details about the study, interview procedure, and requests for brief background information from the patient such as age, diagnosis, time of first encounter with psychiatric care, housing, and employment situation. This was done in order to get a picture of the sample. Respondents were free to choose the location for the interview, with one interview conducted in the respondent's home and all others at the psychiatric clinic. The interviews took about an hour. All interviews were recorded on audiotape and transcribed verbatim including silence and laughter. The interviewer herself had experience working with and interviewing patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. However, she was not involved in the interviewed patients’ treatment.

Analysis

Grounded theory (GT) was used, originally developed by Glaser and Strauss (Citation1967); however, the present study was mainly inspired by Glaser (Citation1978 Citation1992) and Glaser and Holton (2004). Accordingly, analysis was not based on existing theories, but instead strove to be as unbiased and open as possible and to find new understanding and new theories based on the empirical data. It is very important to be open to data and not steered by previous theories and preconceptions in order to ensure the grounding of categories in data. Glaser and Holton (2004) claimed that extensive literature reading before doing analysis is unnecessary. In order to be open to data, the researcher has to accept the confusion and uncertainties emerging from the fact that one doesn′t know what will be found, however, keeping the capacity to make connections and to think multivariately. Classic GT is structured but still a flexible method of analysis. The goal with GT is not descriptive, it is rather to produce a conceptual theory with general implications that is not limited by time and place. The process of analysis consists of a continuous collection of data, coding, conceptual analysis, and memo writing. Line-by-line open coding of data is the first step in this process. Accordingly, the material was first subjected to open coding in which it in its entirety was analyzed and divided into codes. These codes consisted from a few words to several sentences and were given labels in the form of concrete key words, some of them where expressions used by the subjects (in vivo codes). Coding is the foundation of GT and Glazer and Holton (2004) writes:

Incidents articulated in the data are analyzed and coded, using the constant comparative method, to generate initially substantive, and later theoretical, categories. The essential relationship between data and theory is a conceptual code. The code conceptualizes the underlying pattern of a set of empirical indicators within the data. Coding gets the analyst off the empirical level by fracturing the data, then conceptually grouping it into codes that then become the theory that explains what is happening in the data. /…/ Substantive codes conceptualize the empirical substance of the area of research. Theoretical codes conceptualize how the substantive codes may relate to each other as hypotheses to be integrated into the theory. Theoretical codes give integrative scope, broad pictures and a new perspective.

The process involves three types of comparison. Incidents are compared to incidents to establish underlying uniformity and its varying conditions. The uniformity and the conditions become generated concepts and hypotheses. Then, concepts are compared to more incidents to generate new theoretical properties of the concept and more hypotheses. The purpose is theoretical elaboration, saturation and verification of concepts, densification of concepts by developing their properties and generation of further concepts. Finally, concepts are compared to concepts. The purpose is to establish the best fit of many choices of concepts to a set of indicators, the conceptual levels between the concepts that refer to the same set of indicators and the integration into hypotheses between the concepts, which becomes the theory.

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with the research ethics principles recommended for the humanities and social sciences in Sweden (Medical Research Council for Research Ethics, 2003) and in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration (World Medical Association, 2008). The interviewees themselves expressed an interest in being part of the study after reading the informational letter. They themselves contacted or were approached by the author. The voluntary nature of participation was emphasized and that both the interview and continued participation could be terminated at any time on the patient's request. They were further informed that all data would be made anonymous so that respondents would not be recognizable in the final material. Interview transcripts were stored in a password-protected document archive provided with a code. All respondents were offered a copy of the completed work.

Results

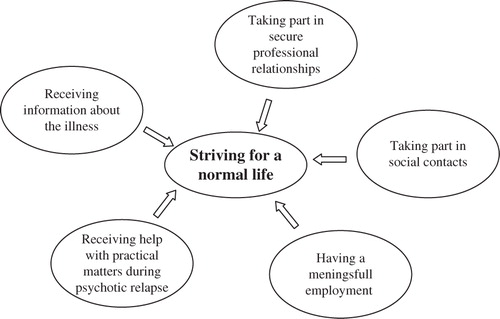

When respondents spoke about their need for help they emphasized their wish to live an ordinary, normal life. To achieve this they engaged in several behaviors and they were asking for help and support in a number of areas, summarized in the following theoretical model () with “Striving for a normal life” as the core category or main concern. The core category was related to the individual's striving for well-being and consisted of their capacity to live a life connected to the degree to which they enjoy possibilities in life in the area of Being reflecting “who one is”; Belonging reflecting the person's belongingness and connection to the social environment; and Becoming reflecting the possibility to reach personal goals, hopes, and aspirations.

Fig. 1. The core category “Striving for a normal life” and related categories describing help needed by patients with schizophrenia in order for them to sustain their well-being.

Receiving information about the illness

Respondents stressed the importance of receiving information about the illness. Several respondents had multiple diagnoses during their time in psychiatry. They felt a lack of information about what it really meant to have these diagnoses and they were asking for more information about their illness.

I didn't know … drifted a little in ignorance about my illness … And so I asked her [the professional], and she said I suffered from schizophrenia … So, it was around 1989 when I learned what was wrong … I still don't understand the word exactly and don't really know what it is, but … it's schizophrenia.

It is important to be informed early about what help there is to be had. You shouldn't have to wait until the patient education program, but instead get it when you're discharged or when you first go the outpatient ward, so you know right away what kind of things you can get help with. And maybe repeat it again after 3 months, because your life might look different then.

First, there was this big “Aha-experience!” for me to hear all the other patients’ thoughts, because I then realized, of course, that some thoughts are actually disease-related, so I didn't need to be ashamed of them, because everyone as crazy as me thinks this weirdly (laughs). It was very nice to have that confirmed in a way /…/ and to then get an explanation for what is happening physically in the brain when things get crazy like this.

We worked a lot with shame, because I felt very ashamed to have this type of disease. You don't want to tell just anybody that you have this kind of illness and so … So I and [professional] worked with that a lot, at least half a year or something like that anyway /…/ and it was really very important to have this discussion about shame, that we had.

I've found it hard to tell people that I'm schizophrenic, because maybe they'd run away … I noticed this old guy at this restaurant I go to /…/ and he always said “Hi there.” One day he saw me standing outside the psychosis treatment clinic smoking. “Oh, are you among these idiots?” he said. “Yeah, sometimes,” I said … so now it's not “Hi there” anymore, but “Uh … hi” keeping his distance like (laughter). So I've never wanted to say what sort of sickness I have.

I used to have friends, but they, like, took off … so now the're gone … They want nothing to do with me anymore … my friends … I don't know why … It's the mental illness they see in weird movies. Yeah, they noticed I acted a little weird sometimes … and then are repelled by it … However, I got to put up with it … You just have to … and start over, maybe.

I don't really know what they talk about there … but it feels like they understand me better now. They don't ask me a lot of things anymore, but they seem to know … and they seem less worried. That feels good.

Taking part in secure professional relationships

The interviewees were describing their need of taking part in secure relationships with people they meet in various support and care efforts. Mainly they expressed the need for continuity in the relationships and the wish to be heard and seen by the professionals.

Several respondents retailed a history of many different health-care contacts. This evoked insecurity, since being frequently faced with new people was experienced as stressful.

Every time you meet a new person, you meet a new universe … so it's good to meet the same person … Otherwise, it can get kind of weird, and you don't want that. You want security, someone who asks how you feel, and some help.

I've been in contact with my case worker, whom I have known for 10 years, a very good person, and she notices how I feel, so it's been great … She's a familiar person, huh? … Otherwise, you get so confused … You go to one person and then to another, but then I call her and I feel that she knows who I am … She's down to earth, well-grounded, and she knows me and knows that sometimes I get very upset and sad. She knows me and she tries to sort out my life and turn it into something good.

When I sit in the waiting room here in the psychosis clinic, I'm not just an anonymous figure in a sofa, but they greet me /…/ It is so important to know that they can see who I am as a person behind the disease.

I think it's wonderful coming here to the clinic. Here, I can unload all my thoughts and problems, both disease-related or non-disease-related. /…/ Today this works a bit like … well, almost like therapy, you could say, in that I come here, I unload my worries, leave, and I am liberated (laughs) and I'd like to keep this contact even if I don't come here so terribly often … But it is important for me to have even this little contact, to feel I have a fixed point if it flares up again, and … It feels really, really safe to be able to come here. And I've had very good contact with [professionals names], and of course I rely on them 100%./…/ It's just because I've had a contact like this, built up over so many years, that there is trust, security, and that I dare to open up and talk about the most private things and so … and of course it takes a while to build that.

I've been in therapy /…/ and it was great. I went to an older woman … You could say that she could see the real me … To sit face to face, as you and I are sitting now … She said “You need someone who sees you.” And some of the things she said startled me. How could she know? … A part of me somehow knew what I needed, of course. … And she saw it.

Taking part in social contacts

Interviewees spoke of the risk of becoming lonely and isolated and how important the opportunity for social contact is for well-being. Therefore, the respondents were attending meeting places and expressing the wish for receiving home visits.

The respondents that regularly visited meeting places for people with psychiatric problems perceived that this type of locale gave a sense of community and opportunity to share experiences.

Thanks to the locale, I was saved. I could go there and meet other patients … And when I met others who'd been in the hospital too, we started laughing, “Well, you were there too and now you're here!” So we could laugh and joke and didn't have to take it so seriously … So that saved me … because my family sure can't … I've been very lonely.

When I get sick, I just lie on the couch … I do everything on the couch, I eat on the couch, watch TV on the couch, sleep on the couch … and everything else falls apart … I fall apart … And then it's good if somebody comes and snaps me out of it.

Having a meaningful employment

Most of those interviewed had some form of work. One was employed full time, while others worked part time with employment arranged by the social insurance office. Respondents stressed the importance of having something to occupy themselves with during the day, either work or other activities.

Working could fulfill several functions, it was perceived both as a way to avoid illness and psychosis and as a motivator to recover from relapse.

Had it not been for work I would have a season pass to the hospital … It feels so good to do something meaningful, not just pretend to work, but to feel that you're doing something qualitative that people actually use …/…/ to feel you can learn new things and grow.

It's very good to have something to do during the day so that you feel like everyone else in society … Yeah, it's nice to have something to do, get away and feel needed … I do not know what I should do if I didn't have my job.

Receiving help with practical matters during psychotic relapse

The respondents described that they had problems taking care of their home, particularly while having a psychotic relapse. Therefore, the need of receiving help with the household in matters such as cleaning and cooking was also stated.

I needed a lot of help, practical help … I wasn't even able to shower, wash myself or do laundry … I couldn't do any housework … I was totally paralyzed … Could not cook either, couldn't even make a sandwich, it took several hours.

Because I got this confusion in my head, this quicksand, I cannot manage a thing … Like money … My family, friends, no one was there to help me manage my expenses … And I was very worried about that …/…/ When you're ill it's important that there's some sort of group to help manage money and ensure that bills get paid, so that you feel some security. They should be able to tell the patient “We'll take care of your bills so you don't need not worry about it.”

Discussion

The participants in the present study described their need for help as mainly linked to their overall life situation rather than just their psychosis, which is in line with previous research (Arvidsson, Citation2001; Foldemo et al., Citation2004; Hansson et al., Citation2001; Slade et al., Citation1996 Citation1998).

Information about the disease was highlighted as important by several respondents in this study. They described difficulties in getting information about what it means to have a psychotic illness. McCabe, Heath, Burns, and Priebe (2002) reported similar results. They had analyzed videotaped meetings between patients with psychosis including schizophrenia and their psychiatrists. They found a pattern in these meetings; patients raised questions about their psychotic symptoms, while the psychiatrists showed discomfort with discussing their symptoms and instead avoided answering patients’ questions. Several of those interviewed in this study had undergone some form of patient education, which they perceived as positive. Previous research shows that education, in addition to increasing patients’ knowledge about their illness, can also reduce relapses and affect patients’ symptoms for the better (Rummel-Kluge & Kissling, Citation2008). Hätönen, Kuosmanen, Malkavaara, and Välimäki (2008) have studied patients’ perception of the information provided in patient education programs and concluded that patients frequently asked for information about their illness, especially about treatment plans and various alternative treatments. They found that professionals failed to provide information to the patients because they took for granted that the patient already had knowledge about their disease, while patients for their part felt they lacked sufficient knowledge about their illness in order to even ask the right questions leading to the desired information. Furthermore, the study pointed to a need for better communication among psychiatry specialties about their patients and that there was a failure to provide adequate information to the patient, since each specialty assumed that another had already provided needed information. To explore and pursue the emotional content—especially the negative emotions—of the patient's narrative may be one way of improving communication with this group of patients (Fatouros-Bergman, Preisler, & Werbart, 2006; Fatouros-Bergman, Spang, Werbart, Preisler, & Merten, 2010). In addition, patients with schizophrenia may suffer from cognitive impairments such as attention and memory deficiencies (Nuechterlein et al., Citation2008). This must also be considered as it can lead to difficulties with processing and remembering information.

The respondents also addressed the value of information to family members. Having a close relative who has a long-term mental illness is often very stressful, especially for the spouse (Östman, Wallsten, & Kjellin, 2005). A meta-analysis reported that patient and family education seem to lower the levels of expressed emotions in the family (Pitschel-Walz, Leucht, Bäuml, Kissling, & Engel, 2001) and reduce relapse in psychosis and hospitalization by up to 20%. Bäuml, Froböse, Kraemer, Rentrop, and Pitschel-Walz (2006) found that education with behavioral components—where the patient and their family received information about the disease, learned problem solving, and about how to deal with relapse—resulted in both decreased number of admissions and shorter hospital stays.

Many of the interviewees had experienced prejudice and rejection from society affecting their social belongingness. Faith, Jewel Sommerville, Origoni and Frederick (2002) found that patients with psychosis had experiences of prejudice and insulting comments from neighbors, and they also felt that they became discredited by media. There was a big concern about being seen in a negative way and they, therefore, avoided talking about their illness. Another study on prejudice against individuals with mental disorders (Lundberg, Hansson, Wentz, & Björkman, 2008) showed that people with psychotic problems had the most experience of social rejection. This was also significantly and negatively related to their perceived quality of life. Angermeyer and Schulze (Citation2001) analyzed the media's impact on the public by looking at attitudes toward people with mental illness before and after violent acts committed by individuals with mental illness. They found that the majority of the press articles that dealt with mental illness did so in connection with a crime of any kind. Schizophrenia, in particular, was almost always treated in association with violent crimes. When looking at public perceptions of patients with schizophrenia before and after media attention associated with violent crime, a high media impact was found such that the reluctance to have a person with schizophrenia as a neighbor or co-worker was raised with each media report.

The interviewees also pointed out the importance of secure relationships to professionals regarding both continuity and being heard and seen, which may have an impact on their sense of Being—reflecting “who one is.” To our knowledge this topic has not been adequately addressed in previous research on the needs of psychotic patients. For example the CAN instrument, with its 22 potential areas of need (Slade et al., Citation1996), does not address any area related to the professional relationship. However, there is some research into the factors that promote recovery from severe mental health problems, which listed the relationship with professionals as an important factor (Borg & Kristiansen, Citation2004; Topor, Citation2001 Citation2004; Topor et al., Citation2006). Accessibility, personal approach, and flexibility are judged as particularly helpful in the recovery process. Perception by patients that the staff was devoting plenty of time was also found to be an important aspect (Topor, Citation2004; Topor et al., Citation2006). Moreover, Svedberg, Jormfeldt, and Arvidsson (2003) found that the professional's ability to pay attention to the patient as a unique individual and to listen and to see them was important for health promotion for patients in psychiatric care; though, this study included several diagnoses beside psychosis. They also found that continuity was important in order to develop trust and promote the interaction with the professional, which is in line with the findings of the present study.

Respondents also addressed the value of social contacts and the risk of becoming isolated. Research on recovery from mental illness indicates the value of meeting people with similar experiences (Topor, Citation2004). Previous research shows that the social networks of people with schizophrenia are significantly poorer than the control group both in quantity and quality, and that half of the schizophrenia patients wanted more social contact (Bengtsson-Tops & Hansson, Citation2001). Furthermore, the same study showed a relationship between dissatisfaction with their social network and higher levels of psychotic symptoms, and that a higher degree of satisfaction with the social network was linked to an increased sense of life quality. Another study examined the characteristics of social support, coping strategies, stressful life events, and their relation to relapse in schizophrenia (Hultman, Wieselgren, & Öhman, 1997). This study showed that a functioning social network was a protection against relapse. The positive effects of a functioning social network in people with schizophrenia are also raised by other researchers as well as the need to take this into account when planning treatment (Kopelowicz, Liberman, & Wallace, 2003; Yank, Bentley, & Hargrove, 1993). The importance of a social network is also stated in research about other groups of patients receiving psychiatric care (Svedberg, Jormfeldt, Fridlund, & Arvidsson, 2004).

Furthermore, respondents spoke about the importance of having meaningful employment reflecting their need to reach personal goals, hopes, and aspirations, an important component of well-being. Previous research addresses this factor and points to the benefits of having a job in an ordinary workplace but adjusted to the individual's ability (Bond et al., Citation2001). This is believed to contribute to both increased self-esteem and to better management and reduction of symptoms including negative, positive, and depressive symptoms (Bell & Milstein, Citation1993). The most important factor for the well-being and self-esteem of people working in so-called sheltered workplaces was that other people felt that their work was important (Dick & Shepherd, Citation1994), meaningful, and meant something to others (Yilmaz, Josephsson, Danermark, & Ivarsson, 2009). To have a profession seems to have a number of benefits for people with schizophrenia and raises the importance of cooperation between different care and support structures to facilitate entry into the employment market (Cook & Razzano, Citation2000).

Finally, the need for independent-living support was emphasized by the interviewees in the present study. It was previously found that most mentally ill patients wanted to stay in their own apartment (Forshuk, Nelson, & Brent Hall, 2006; Seilheimer & Doyal, Citation1996). Independent living was linked both to an increased sense of competence and confidence and to greater satisfaction with ones’ accommodations (Seilheimer & Doyal, Citation1996). However, access to various support activities was requested, preferably with a flexibility that would permit 24-hour availability (Forshuk et al., Citation2006). Additionally, having one's own accommodations was highlighted as something that gave hope and an opportunity to plan ahead (Forshuk et al., Citation2006). Padgett (Citation2007) showed that an independent accommodation provided a basic security for individuals with mental health problems. Having a home inspired a sense of control and daily household activities resulted in a sense of security via daily schedules and continuity.

Methodological considerations

The strength of this study is that it explores a topic in need of more research. Patients with schizophrenia and psychosis may have a hard time actually formulating their concerns and this type of study contributes to their empowerment. However, the main limitation of this study is the few participants. In order to attain a diverse sample we asked about some background characteristics. We conclude that our sample was diverse in age but not in gender as almost all participants were female. Furthermore, all interviewees lived in urban areas. However, these imbalances in the sample do not necessary need to be a bias, as research on assistance needs in patients with schizophrenia do not find differences due to gender or urban/rural life (Arvidsson, Citation2001; Foldemo et al., Citation2004; Hansson et al., Citation2001; Slade et al., Citation1996 Citation1998), and this may therefore not limit the transferability of the results. Possibly the fact that some of the interviewees have once been treated in the old mental hospitals may have affected the results, as some of their experiences may have been specific for that period of time and not representative for contemporary psychiatry. Nevertheless, these experiences are still important. One of the interviewees had not been diagnosed with schizophrenia yet was still included in this study, as this person still had many years of experience of having a psychotic illness. A check revealed that this person's answers gave richness to the material and did not differ to any great extent from the others’ stories concerning main themes. However, the transferability of the results may still be restricted by the few subjects, and therefore more research needed within this area.

Conclusions

To conclude; the participants in the present study described their need for help as mainly linked to well-being in their overall life situation to the areas of Being, Belonging, and Becoming rather than just to their psychosis, which is in line with previous research. What is new in the present study is the emphasis on the need for secure relationships with professionals, reflecting the need to be heard and seen. To our knowledge this topic has not been extensively addressed in previous research on the needs of psychotic patients, though this topic was mainly found in psychiatric patients in general (Svedberg et al., Citation2003) and more research on this subject in relationship to psychosis is therefore required.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study.

References

- Angermeyer M. C. Schulze B. Reinforcing stereotypes: How the focus on forensic cases in news reporting may influence public attitudes towards the mentally ill. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 2001; 24: 469–486.

- APA. DSM-IV. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders4th edn. American Psychiatric Association. Washington DC, 1994

- Arvidsson H. Needs assessed by patients and staff in a Swedish sample of severely mentally ill subjects. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 2001; 55: 311–317.

- Bäuml J. Froböse T. Kraemer S. Rentrop M. Pitschel-Walz G. Psychoeducation: A basic psychotherapeutic intervention for patients with schizophrenia and their families. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006; 32: 1–9.

- Bell M. D. Milstein R. M. Pay and participation in work activity: Clinical benefits for clients with schizophrenia. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1993; 17: 173–177.

- Bengtsson-Tops A. Hansson L. Quantitative and qualitative aspects of the social network in schizophrenic patients living in the community. Relationship to sociodemographic characteristics and clinical factors and subjective quality of life. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2001; 47: 67–77.

- Bond G. R. Becker D. R. Drake R. E. Rapp C. A. Meisler N. Lehman A. F, et al.. Implementing supported employment as an evidence-based practice. Psychiatric Services. 2001; 52: 313–322.

- Borg M. Kristiansen K. Recovery-oriented professionals: Helping relationships in mental health services. Journal of Mental Health. 2004; 13: 493–505.

- Cook J. A. Razzano L. Vocational rehabilitation for persons with schizophrenia: Recent research and implications for practice. Schizophrenia Bulletin. Special Issue: Psychosocial Treatment for Schizophrenia. 2000; 26: 87–103.

- Dick N. Shepherd G. Work and mental health: A preliminary test of Warr's model in sheltered workshops for the mentally ill. Journal of Mental Health. 1994; 3: 387–400.

- Faith B. D. Jewel Sommerville A. E. Origoni N. B. R. Frederick P. Experiences of stigma among outpatients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2002; 28: 143–155.

- Fatouros-Bergman H. Preisler G. Werbart A. Communicating with patients with schizophrenia: Characteristics of well functioning and poorly functioning communication. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006; 3: 121–146.

- Fatouros-Bergman, H., Spang, J., Werbart, A., Preisler, G., & Merten, J. (2010). Interplay of gaze behaviour and facial affectivity in schizophrenia. Psychosis. , 1–3.

- Flyckt, L. (2008). Regional Care Guidlines: Schizophrenia and other psychosis. Stockholm: Stockholm County Council.

- Foldemo A. Ek A-C. Bogren L. Needs in outpatients with schizophrenia, assessed by the patients themselves and their parents and staff. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2004; 39: 381–385.

- Forshuk C. Nelson G. Brent Hall G. B. “It's important to be proud of the place you live in”: Housing problems and preferences of psychiatric survivors. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. 2006; 42: 42–52.

- Glaser B. G. Theoretical sensitivity: Advances in the methodology of grounded theory. Sociology Press. Mill Valley CA, 1978

- Glaser B. G. Basics of grounded theory analysis: Emergence vs forcing. Sociology Press. Mill Valley CA, 1992

- Glaser B. G. Strauss A. L. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine. Chicago, 1967

- Glaser, B. G., with the assistance of Holton, J. (2004). Remodeling grounded theory. [80 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung [Forum: Qualitative Social Research]. , 5(2), Art. 4. Retrieved January 5, 2011, from http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs040245.

- Häfner H. Hambrecht M. Loffler W. Munk-Jorgensen P. Riecher-Rossler A. Is schizophrenia a disorder of all ages? A comparison of first episodes and early course across the life-cycle. Psychol Med. 1998; 28: 351–365.

- Häfner H. Maurer K. Loffler W. an der Heiden W. Hambrecht M. Schultze-Lutter F. Modeling the early course of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2003; 29: 325–340.

- Hallberg L. R.-M. The “core category” of grounded theory: Making constant comparisons. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being. 2006; 1: 141–148.

- Hallberg, L. R.-M. (2010). Some thoughts about the literature review in grounded theory studies. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being. , 5, 5387, 10.3402/qhw.v6i1.5412.

- Hansson L. Sandlund M. Bengtsson-Tops A. Bjarnason O. Karlsson H. Mackeprang T, et al.. The relationship of needs and quality of life in persons with schizophrenia living in the community. A Nordic multi-center study. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 2003; 57: 5–11.

- Hansson L. Vinding H. R. Mackeprang T. Sourander A. Werdelin G. Bengtsson-Tops A, et al.. Comparison of key worker and patient assessment of needs in schizophrenic patients living in the community: A Nordic multicentre study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2001; 103: 45–51.

- Hätönen H. Kuosmanen L. Malkavaara H. Välimäki M. Mental health: Patients’ experiences of patient education during inpatient care. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2008; 17: 752–762.

- Hultman C. M. Wieselgren I.-M. Öhman A. Relationships between social support, social coping and life events in the relapse of schizophrenic patients. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 1997; 38: 3–13.

- Kopelowicz A. Liberman R. P. Wallace C. J. Psychiatric rehabilitation for schizophrenia. International Journal of Psychology & Psychological Therapy. 2003; 3: 283–298.

- Lindamer L. A. Bailey A. Hawthorne W. Folsom D. P. Gilmer T. P. Garcia P, et al.. Gender differences in characteristics and service use of public mental health patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2003; 54: 1407–1409.

- Lundberg B. Hansson L. Wentz E. Björkman T. Stigma, discrimination, empowerment and social networks: A preliminary investigation of their influence on subjective quality of life in a Swedish sample. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2008; 54: 47–55.

- McCabe R. Heath C. Burns T. Priebe S. Engagement of patients with psychosis in the consultation: Conversation analytic study. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 2002; 325: 1148–1151.

- Medical Research Council for Research Ethics. (2003). Ethical guidelines for medical human research. Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Meltzer H. Y. Suicidality in schizophrenia: A review of the evidence for risk factors and treatment options. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2002; 4: 279–283.

- Nuechterlein K. H. Green M. F. Kern R. S. Baade L. E. Barch D. M. Cohen J. D, et al.. The MATRICS consensus cognitive battery, part 1: Test selection, reliability, and validity. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008; 165(2): 203–213.

- Östman M. Wallsten T. Kjellin L. Family burden and relatives’ participation in psychiatric care: Are the patients diagnosis and the relation to the patient of importance?. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2005; 51: 291–301.

- Padgett D. There is no place like (a) home: Ontological security among persons with serious mental illness in the United States. Social Science & Medicine. 2007; 64: 1925–1936.

- Pitschel-Walz G. Leucht S. Bäuml J. Kissling W. Engel R. R. The effect of family interventions on relapse and rehospitalization in schizophrenia—A meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2001; 27: 73–92.

- Preston N. J. Orr K. G. Date R. Nolan L. Castle D. J. Gender differences in premorbid adjustment of patients with first episode psychosis. Schizophrenia Research. 2002; 55: 285–290.

- Renwick R. Brown I. Being, belonging, becoming: The Centre for Health Promotion model of quality of life. Quality of life in health promotion and rehabilitation: Conceptual approaches, issues, and applications. Renwick R. Brown I. Nagler M. Sage. Thousand Oaks CA, 1996

- Rummel-Kluge C. Kissling W. Psychoeducation in schizophrenia: New developments and approaches in the field. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008; 21: 168–172.

- Salokangas R. K. Honkonen T. Saarinen S. Women have later onset than men in schizophrenia—but only in its paranoid form. Results of the DSP project. Eur Psychiatry. 2003; 18: 274–281.

- Seilheimer T. A. Doyal G. T. Self-efficacy and consumer satisfaction with housing. Community Mental Health Journal. 1996; 32: 549–559.

- Slade M. Phelan M. Thornicroft G. A comparison of needs assessed by staff and by an epidemiologically representative sample of patients with psychosis. Psychological Medicine. 1998; 28: 543–550.

- Slade M. Phelan M. Thornicroft G. Parkman S. The Camberwell Assessment of Need (CAN): Comparison of assessments by staff and patients of the needs of the severely mentally ill. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1996; 31: 109–113.

- Svedberg P. Jormfeldt H. Arvidsson B. Patients’ conceptions of how health processes are promoted in mental health nursing. A qualitative study. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 2003; 10: 448–456.

- Svedberg P. Jormfeldt H. Fridlund B. Arvidsson B. Perceptions of the concept of health among patients in mental health services. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2004; 25: 723–736.

- Topor A. Managing the contradictions: Recovery from severe mental disorders. Stockholm University Department of Social Work. Stockholm, 2001

- Topor A. What helps? Recovering from mental illness. Natur och Kultur. Stockholm, 2004

- Topor A. Borg M. Mezzina R. Sells D. Marin I. Davidson L. Others: The role of family, friends and professionals in the recovery process. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation. 2006; 9: 17–37.

- Usall J. Ochoa S. Araya S. Marquez M. Gender differences and outcome in schizophrenia: A 2-year follow-up study in a large community sample. Eur Psychiatry. 2003; 18: 282–284.

- World Medical Association. (2008). Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Seoul: World Medical Association.

- Yank G. R. Bentley K. J. Hargrove D. S. The vulnerability-stress model of schizophrenia: Advances in psychosocial treatment. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1993; 63: 55–69.

- Yilmaz M. Josephsson S. Danermark B. Ivarsson A.-B. Social processes of participation in everyday life among persons with schizophrenia. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being. 2009; 4: 267–279.