Abstract

The aim of this study was to generate a substantive theory, based on interviews with women with fibromyalgia, explaining how they manage their main concerns in daily life. The study has an inductive approach in line with classic grounded theory (Glaser, 1992). Twenty-three women living in the southwest region of Sweden were interviewed in-depth about their daily living with fibromyalgia and problems related to this. Probing and follow-up questions were asked by the interviewers when relevant. The interviews were transcribed verbatim and consecutively analysed in line with guidelines for grounded theory. The results showed that the main concern for women with fibromyalgia was to reach a balance in daily life. This concern was resolved by them using different strategies aimed at minimizing the dysfunctional interplay between activity and recovery (core category). This imbalance includes that the women are forcing themselves to live a fast-paced life and thereby tax or exceed their physical and psychological abilities and limits. Generally, the fibromyalgia symptoms vary and are most often unpredictable to the women. Pain and fatigue are the most prominent symptoms. However, pain-free periods occur, often related to intense engagement in some activity, relaxation or joy, but mainly the “pain gaps” are unpredictable. To reach a balance in daily life and manage the dysfunctional interplay between activity and recovery the women use several strategies. They are avoiding unnecessary stress, utilizing good days, paying the price for allowing oneself too much activity, planning activities in advance, distracting oneself from the pain, engaging in alleviating physical activities, and ignoring pain sensations. Distracting from the pain seems to be an especially helpful strategy as it may lead to “pain gaps”. This strategy, meaning to divert attention from the pain, is possible to learn, or improve, in health promoting courses based on principles of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). We suggest that such courses are offered in primary care for patients with fibromyalgia or other types of longstanding pain. The courses should be led by registered nurses or psychologists, who are experienced in CBT and have extensive knowledge about theories on longstanding pain, stress and coping. Such courses would increase well-being and quality of life in women suffering from fibromyalgia.

Introduction

Fibromyalgia is a condition characterized by long-standing widespread pain and increased pain sensitivity, but patients also report fatigue, insufficient sleep, headache, cognitive disturbances and different somatic symptoms. The prevalence of fibromyalgia is estimated to 0.5–5% of the general population with a strong predominance of women (Neumann & Buskila, Citation2003). Despite of many years of research, the aetiology of fibromyalgia is still unclear and the diagnosis is based on criteria from the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) (Wolfe et al. 1990). According to the ACR 1990 criteria, a patient is said to suffer from fibromyalgia if two criteria are satisfied: (1) widespread pain, lasting for 3 months or more and (2) eliciting of pain by palpation of, at least, 11 out of 18 predetermined bilateral tender points (Wolfe et al., Citation1990). These criteria have been criticized for not being useful in the clinic. Symptoms may vary over time and the tender point count at specific sites has been rightfully criticized. New diagnostic criteria are proposed that no longer relies on tender point count, but combines a widespread pain index with a symptom severity scale, that also includes fatigue, insufficient sleep, cognitive, and somatic symptoms (CitationWolfe et al., 2010). The impaired sleep is characterized by never getting a good night's sleep and waking up several times a night. The pain related to fibromyalgia can vary from a dull type of pain to a more intensive and distinct pain. Söderberg, Lundman and Norberg (Citation2002) found in their study on women with fibromyalgia that pain caused fatigue which in turn strengthened the pain. This means that experiences of pain and fatigue are intertwined.

Earlier hypotheses assumed that fibromyalgia reflects muscular symptoms or psychic distortions in the patient, such as masked depression and/or pain-prone personality (Blumer & Heilbronn, Citation1982). Such hypotheses are widely criticized and results of studies on affective disturbances in patients with long-standing or chronic pain are inconsistent. More recent studies suggest that functional disturbances in pain modulating pathways in the central nerve system could explain the fibromyalgia symptoms. Jensen (Citation2009) found decreased activity in parts of the brain that are obstructing pain experiences. She did not find any relationships between fibromyalgia and anxiety and/or depression. Symptoms related to fibromyalgia are commonly amplified by high levels of stress over a long period of time (Wyalonis & Heck, Citation1992). Henriksson, Carlsberg, Kjällman, Lundberg and Henriksson (Citation2004) reported that pain gradually had spread from being “localized” to being “wide-spread” in 80% of a group of patients with fibromyalgia. Presumably, the fibromyalgia syndrome cannot be explained and understood by a single biomedical predictor only. Rather, a bio-psycho-social model can be assumed where peripheral musculoskeletal symptoms and the nociceptive system interact with cognitive, emotional and behavioural factors in a social context.

A clinical experience is that patients with fibromyalgia often are perfectionists with a high need for achievement and perseverance. In-depth interviews with women suffering from fibromyalgia (Hallberg & Carlsson, Citation1998a) illuminated psychologically traumatic life histories including early loss, social problems and high levels of responsibility early in life. A similar study, based on interviews with women diagnosed with fibromyalgia (Wentz, Lindberg, & Hallberg, 2004), also reported life histories marked by high levels of psychological and physical strain. Feelings of being neglected or being exposed to exceedingly high demands from parents during childhood can result in uncertainty and stress; a situation which is difficult to manage emotionally in childhood. It was obvious in the interviews by Wentz et al. (2004) that signals of pain and fatigue were ignored by the adult women and that they were “over-active” and preoccupied by the needs of and worries about others. Women with fibromyalgia often speak about triggering conditions, such as infections, psychologically traumatic events or longstanding stress conditions, preceding the debut of their fibromyalgia symptoms (e.g., Hallberg & Carlsson, Citation1998a; Wentz et al., Citation2004).

Current treatment of patients diagnosed with fibromyalgia mainly concerns symptom reduction and self-management strategies (Nielsen, Jensen, & Hill, 2001). Activity pacing is included in self-management and means spacing activities throughout the day. Managing energy wisely may increase control over pain. Also, individuals who suffer from persistent pain conditions have to develop coping strategies in order to manage, reduce or endure their pain in daily life (Hallberg & Carlsson, Citation1998b; Hallberg & Carlsson, Citation2000). Coping aims at altering, managing or tolerating a stressful situation and, therefore coping should not been classified as either “good” or “bad” (e.g., Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984). However, passive coping strategies have been reported to co-vary with psychological distress and depression in patients with chronic pain (Nicassio, Radojevic, Schoenfeldd-Smith, & Dwyer, Citation1995). Fibromyalgia has most often been investigated from a biomedical perspective in order to explore its aetiology. Also, several studies have illuminated that living with fibromyalgia implies a serious impact on daily life (e.g., Arnold et al, 2008; Schaefer, Citation2005; Söderberg & Lundman, Citation2001). This study takes another angle and aims at gaining a deeper understanding of what is the main concern in daily life for women living with fibromyalgia. The intention is to generate a substantive theory explaining what women with fibromyalgia are doing to manage their main concern in daily living with longstanding pain and fatigue.

Method

This study has an inductive approach and relies on the subjective experiences of women with fibromyalgia themselves. The grounded theory approach, originally developed by Glaser and Strauss (Citation1967), has its theoretical roots in pragmatism and symbolic interactionism and aims at generating theoretical explanations of empirical data. According to Plummer (Citation2001) pragmatism includes: to unify intelligent thoughts, logical method, practical actions and apply to experiences. Basically, symbolic interactionism is a sociological perspective claiming that the meaning of phenomena and events is constructed, interpreted and modified in social interactions. Some years after presenting grounded theory, Glaser and Strauss ended their cooperation and used their own versions of the method. Glaser's version is labeled “classic grounded theory” (Glaser, Citation2003) whereas Strauss together with Juliet Corbin developed a “reformulated grounded theory” (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2008). Also, a “constructivist grounded theory” has been presented by Charmaz (Citation2006). The fundamental characteristics of grounded theory are similar in the three versions but some ontological and epistemological differences have been assumed (Hallberg, Citation2006). In this study we used Glaser's classic version of grounded theory. In line with guidelines for classic grounded theory, the intention was that preconceptions, including existing research results, would influence the research process as little as possible, i.e., interviews as well as analysis of data. We tried hard to be open and unprejudiced when listening to the narratives of the informants and, also, tried hard to show “disciplined restraint” concerning preconceptions and interpretations of data (Hallberg, Citation2006). The result of a classic grounded theory study can be presented as a hypothesis that can be further tested in quantitative or qualitative studies or as a substantive theory that explains the studied area. Our intention was to generate a substantive theory, explaining what is the main concern for women living with fibromyalgia and how do they manage this.

Participants

The total sample (composed of subsample I and II) consisted of 23 women with fibromyalgia living in the southwest region of Sweden. The total sample was heterogeneous in regards to age, civil status, education, professional background and degree of active membership in a support group. Subsample I included 11 women (mean age = 54.4 years) who fulfilled the ACR criteria, which were verified in their medical records no more than 5 years back by the second author (SB), who is a general practitioner. The medical records were available at the hospital for rheumatology in the region or at the women's local general practitioners. The emerging results from the data of subsample I was supplemented by data from subsample II. This subsample consisted of 12 women (mean age = 53.3 years) with fibromyalgia, who were active members of a local fibromyalgia support group in the Gothenburg region. The medical records for this subsample were not available or requested by the researchers. By using these two subsamples of women, our intention was to optimize the variation in data, which is intended for data in grounded theory studies.

Procedure

Taped interviews, lasting between 1 and 2 h, were conducted with each woman by a psychologist/PhD (subsample I) and by the first author (subsample II). The interviews were open and focused on the women's reflections and thoughts about their daily living with fibromyalgia. The interviewers asked appropriate probing and follow-up questions when relevant, for example concerning pain debut and pain development, periods of absence of pain, personality, life history, and social relationships. During the interviews each woman had the opportunity to raise questions of importance to her. Data from the two subsamples (subsample I and II) were constantly contrasted with each other to illuminate differences and similarities in the data. Emerging results from the simultaneous process of collecting and analysing data guided further questioning, i.e., theoretical sampling. The theoretical sampling aimed at receiving thick descriptions and continued until saturation was met, which occurred when new data did not provide any new information.

Analysis of data

The 23 interviews were transcribed verbatim and each interview was preliminary analysed as soon as it was transcribed. In an open coding process line-by-line, substantive codes were identified and labelled concretely. These substantive codes illuminated “what the data was about”, i.e., the meaning of the data. Substantive codes with similar meanings were then clustered into comprehensive categories, which were labelled on a more abstract level. Further, the women's main concern—“what is the main problem in daily life”— was found to be their striving to reach a balance in daily life. In the next phase of the analysis, each emerging category was further elaborated and its properties or dimensions were illuminated, saturated and labelled. The data was subsequently scrutinized to find out how the women managed their main concern in daily life. This main concern (i.e., to reach a balance in daily life) was resolved by the core category, identified and labelled as minimizing the dysfunctional interplay between activity and recovery. The relationships between the core category and all other categories were then sought in a pattern identification phase. By this, a substantive theory was formed, explaining how the main concern for women living with fibromyalgia was managed. During the entire process of data collection and analysis memos were written. The memos or notes concerned emerging hypothetical ideas based on the data; ideas, which were continuously compared to data.

Ethical considerations

The study design was approved by the Local Ethics Group, Halmstad University in Sweden (Nr 90–2006–1150). All informants were given written and verbal information about the study in line with Swedish law (SFS Citation2003:460). They were informed that their participation in the study was voluntary and that they could interrupt their participation at any time without explaining the cause. They also had the opportunity to ask questions about the study, and receive answers, before an informed consent was signed. Because of the potential sensitivity of the topic for interview, professional back up was secured. However, no informant had any need for these services.

Results

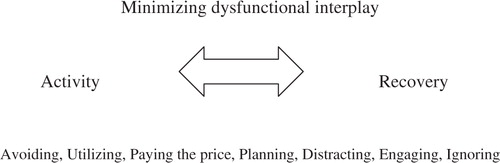

Based on the analysis of the verbatim transcribed interviews a substantive theory was generated, explaining how the main concern for women with fibromyalgia was managed by them. According to the data, the main concern for women with fibromyalgia was to reach a balance in their daily life. The women stated that they were forcing themselves to live a fast-paced life and thereby they were exceeding their physical and psychological abilities and limits. Related to this, widespread pain, restricted mobility and strength as well as severe fatigue had been developing successively. In order to minimize the dysfunctional interplay between activity and recovery (core category), the women use different coping strategies, i.e., avoiding unnecessary stress, utilizing good days, paying the price for allowing oneself too much activity, planning activities in advance, distracting oneself from the pain, engaging in alleviating physical activities and ignoring pain sensations (see ). According to the interviews, shorter or longer pain-free periods occur in most women. These periods are often related to engagement in some form of activity, relaxation, massage, Chi Gong or sexual intercourse, but mainly the pain free-periods are unpredictable to the women. The fibromyalgia symptoms are also unpredictable and random and challenging to accept by the women. According to the data, physical appearance is important to the women, such as make-up, hair-style and clothing, and they strive to keep up appearances. People in their surroundings often distrust or question their pain and illness because the women look so fit and fresh, but their appearances are deceptive.

Figure 1. A substantive theory was generated, explaining how the main concern for women with fibromyalgia (i.e., to reach a balance in everyday life) was resolved by minimizing the dysfunctional interplay between activity and recovery (i.e., core category). Several strategies, related to the core category, were used, above briefly called avoiding, utilizing, paying the prize, planning, distracting, engaging and ignoring.

Minimizing dysfunctional interplay between activity and recovery—the core category

According to the interview data, the women have been forcing themselves to be “good and responsible girls” as long as they can remember and have an extremely high tempo in their daily life, bordering on over-activity. Generally, they are forcing themselves to live a fast-paced life. They describe themselves as active, responsible and helpful persons who have difficulties asking for help. They seem to tax or exceed their physical and psychological abilities and limits in order to satisfy their own needs and demands and/or to be acknowledged and appreciated by people in their surroundings. Their intense activity level is seldom matched with relevant time for recovery—rather an obvious imbalance exists. Some women say that they are similar to their mothers in this respect, which, according to the women, might indicate that over-activity is a behaviour that is repeated over generations. Some women spoke about high demands from parents, unmet basic needs and being disliked or not fully accepted by parents during the years of growth. The data contains obvious signs of an increased level of mental load and a decreased level of parental support during childhood. One woman in the study said that:

“fibromyalgia is caused by your life history and you have to change your way of living in time, for example avoiding double jobs (full-time at home and at work) and striving for high status. You have to economize on yourself”.

The pain related to fibromyalgia is widespread but changes its location and intensity quite randomly, which makes the women's conditions and abilities unpredictable. These conditions also force them to “live one day at a time” and adjust their living to the actual pain and fatigue. However, the pain alone does not make the women “sick persons” rather the pain together with a paralysing tiredness and lack of energy, related to an insufficient sleep, is a considerable restricting factor for them in daily life. The fatigue is like a “heavy rain” falling over them and is not possible to stop or relieve. The women report deteriorated memory and motor function as well as decreased concentration abilities as parts of their perceptions of the fibromyalgia symptoms. Stress is their “worst enemy” and they have to keep distress out of sight in order to find an acceptable balance in daily life. If they demand too much of themselves or keep too many future plans in their head, the pain will increase. When they have fun together with other people or when they are engaged in something that they really appreciate, they can forget both time and space. This state has similarities with being in a “flow” (Csikszentmihaly & Rathunde, 1993) and leads to a state where the pain is occasionally absent. According to the data, this occasional absence of pain, or “pain gap”, can vary between lasting <1 h up to several days or months. Warmth, relaxation, massage, Chi-Gong, dancing, sexual intercourse, and joy can also lead to periods of absence of pain—during shorter or longer periods of time. The three quotes below intend to illustrate the women's perspective on their situation:

I was working full-time, managing the home all by myself and also spending a lot of time in the garden as I thought it was so much fun and where I wouldn't have let my husband to go either. I was also involved in the Parent Teacher Association and had a period of time where I was working for the union. Yes, it was too much, at full speed. My body reacted and told me I had to calm down and so I did for a period of time while I was in pain. Then I got better again and started over at the same pace again.

I am an overly stressed person and I need to get everything done in the same day. The older I get the more I try to wind down, but it's very hard to unwind. When I wake up every day I think about what I have to do during the day. And I have to reach those goals. I think I've always been like this.

My stamina is gone. I can't handle pushing myself, I have no patience anymore, my body cannot handle it. I'm completely exhausted mid-day. By the time, I feel as if I can't take anymore, it's actually so serious that my entire body starts to shake. That's when I've pushed myself too hard. I'm the kind of person who is always there to help others. Sometimes I push myself to do things that I'm really too exhausted to handle.

Avoiding unnecessary stress

The women stated that they try hard to portion their energy and to reduce their activity in order to avoid unnecessary stress as a strategy to reach a balance in daily life. These strategies are often called activity pacing techniques. Negative stress makes their pain even worse, for example when they have to do things that they cannot master sufficiently or over which they do not have any control. Such situations cause unnecessary irritation and stress which increases the pain considerably. Often they are too ambitious and hardworking and have difficulties remembering the importance of keeping distress out of sight. Many women acknowledge that they do not have the strength and energy enough to do all the tasks they are actually doing. They often make demands on themselves to be competent and helpful and have great difficulties making it plain that they hesitate to do things that create negative stress. Some women in the study have gone through intervention courses to learn positive thinking and to prioritize their own needs and wishes. Although they are aware of the importance of setting limits, prioritizing themselves and to sometimes say “No” in order to conserve energy and reduce stress, they have difficulties not to please other people. This especially applies to their children, husband, friends and workmates.

Sometimes when I feel like I have taken on too much I wonder: why did I do this? I mean then I have both the fact that I agreed to take this on and that I walk around and dwell on it—why wasn't I able to say no? I mean then you automatically fall in to a state of tension and pull up your shoulders, become angry and irritated and start feeling pain.

You can like tidy up or work in the garden, but this thing when you do things you really don't have the energy for … but it's typical and that you don't think about it until you start hurting …

Stress is my worst enemy. If there's chaos around me it doesn't take much before I start feeling pain. I cannot schedule too many things in one day. I can't have too many things going on at the same time and I can't exhaust myself either because then those setbacks appear with pain in my body. You get terribly tired, a tiredness that cannot be rested away.

Utilizing good days

Pain-free days are good days during which the women then feel healthy and strong. They try to accomplish as much as they possibly can during these days. Often they have slept satisfying the night before and because they are rested they also wake up early. Everyone in the family feels well during such days; the woman feels like a happy woman and caring mother. She can for example start the day by making bread for the family, cleaning up the house, do the laundry and then play with the children and/or have a picnic with them outdoors. During a good day, the women prioritize being good and caring mothers and put their children in the centre. However, it is difficult to predict if the next day will be a good day or not—there are no signs or indications in advance, so the women have to take each day as it comes.

If I wake up in the morning and am not dead tired when I open my eyes but perhaps only a little tired, then I know that this can be a good day. If I know that I'm having a good day it's for certain that two to four days will be bad. Even if I try to take it easy that good day.

During the bad days the kids don't have to clear the kitchen table because it's easier if I do it myself as I don't want the sink to be in chaos. I don't end up playing a lot with the children, they play by themselves. I make sure that they get to and from school, are fed and get dressed. Maybe I'll give them biscuits and buns as a snack during the middle of the week – other times it's mostly fruit but during a bad day I don't have the strength to peel apples and oranges.

Paying the price for allowing oneself too much activity

One strategy which women with fibromyalgia use to manage their life situation is to allow themselves to take part in social gatherings despite the awareness that they will have to pay the price for it afterwards. However, they are convinced that they will recover from pain and fatigue afterwards, with or without support from medications or other treatments. In a way they generally accept their suffering from fibromyalgia but are not prepared to live a life completely void of parties and joy together with other people. Sometimes they want to have fun like people in general and are therefore willing to pay the price. Parties, concerts and dancing are examples of activities that women sometimes allow themselves despite knowing the consequences—sometimes it entails several days of increased pain and fatigue.

I'll pretty much dance to every song during a dance evening. Then we go home after the last dance and getting out of the car can be sheer hell – my feet ache, my legs ache, my back aches and the day after you can't really do a whole lot. But it's worth it because it was so much fun.

I had to call the doctor after I had been to a wedding and tell him that I'm going to need a couple of shots. I had been dancing and had a blast but I know that I'll end up having a lot of pain if I dance an entire evening. But it's worth it, you have to live. I don't bury myself entirely. I don't sit down in a corner and say I can't do something because I'm in pain.

Planning activities in advance

Despite the unpredictability of pain and fatigue, one strategy to handle the situation is to plan activities in advance and also to manage the level of activity. It seems to be extremely important not to plan too much activity during one specific day but rather to find the reasonable level of activity and strain that does not lead to increased pain. If something physically or mentally demanding is planned, the woman has to rest one or more days before the event to gather the necessary strength to carry the planned task through. If for example a woman with fibromyalgia is invited to her child's school for a parents’ evening (about a 15-minutes discussion) regarding the child's development and performance at school, she strives to be rested and alert by having a good rest before the meeting. This means that she has to conserve energy to reduce the stress related to the planned activity. One woman describes how she prepared herself for busy days:

Yes, I lie down during the mornings. I don't have to get up early in the morning, I take it very easy. I make myself a cup of tea, get the newspaper and lie in my bed until I feel like I can get up. Then I take a warm shower, really warm. At that point I feel ready to tackle the day. I try to spend time doing things I think are fun. I think that it's better to stay up at night since that's when all the fun happens.

Distracting oneself from the pain

To divert attention from the pain can contribute to occasional absence of pain or “pain gaps”. When the women are doing something that captures their interest and engagement, they become completely absorbed in what they are doing and forget their suffering. The pain is no longer at the front of their awareness; rather it moves to the background and is no longer in their consciousness all the time. One woman said that “I think the pain is still there when you are doing something fun, but you focus so much on the fun thing so you forget the pain … but it is still there, but you don't feel it.” When the women have fun together with other people or when they are engaged in something that they really appreciate, they can distract themselves from the pain and forget both time and space. One woman said:

“I had a pain gap for 14 days during my vacation abroad, it was a lot to see and do there so I forgot the pain... I totally forgot that I had pain. And it was also something with the conditions there... that it was so warm and wonderful.”

My energy level is at its highest when I'm doing something fun, when I go out dancing, which I love doing. People are amazed that I can handle dancing. But it makes me feel better. I think that what happens is that body muscles relax with the music. You kind of relax from the music, itss a little psychological, you confuse the pain. It's important to try to do it to make things easier for yourself, I think.

In actuality I think that it's the mind … I think that's what is controlling it. When I enter the public bath, the entire atmosphere there, my friends, the warm water, salt water and then … then I kind of feel like I am not sick … or am in any pain. It's really warm and really nice … if that is a pain gap or if I'm simply disregarding it, that I don't know.

Engaging in alleviating physical activities

Physical activities in reasonable doses and intensity are perceived by women with fibromyalgia as necessary to take part in. Our data shows that walks, gymnastics, massage, Chi Gong and easy dancing are examples of physical activities preferred by many women in alleviating pain and stiffness. The women argue that they have to move themselves to a reasonable extent in order to manage the pain and stiffness and to feel as good as possible. However, if the physical activity is too demanding or if the woman forces herself to exaggerate the activity, the pain and stiffness will rather increase than decrease. The same is true for repetitive motions—something the women say they have to avoid. Also, insufficient physical effort will lead to increased pain and more stiffness. Meditation is one form of an alternative activity that seems to appeal to women with fibromyalgia. Chi-Gong and acupuncture are also reported by women with fibromyalgia to provide relaxation and sometimes even pain gaps, for shorter or longer periods. In general, women with fibromyalgia try many different traditional as well as alternative methods to find a reasonable balance between activity and recovery for managing pain, stiffness and fatigue and optimizing their well-being.

Yes, I can have pain gaps. It's when I move around and if I'm out moving around and walking around in the garden, then I don't feel it (the pain). If it's possible to be absorbed in what you're doing or …? But if I'm inside and moving around, like for example if I'm walking around … cleaning up or baking or whatever, then I do feel the pain.

Ignoring pain sensations

Commonly, the women commit 100% of their energy to their work and whatever they are doing and gladly a bit more if possible. They say that they force themselves to fulfill their work tasks despite having severe pain, stiffness and fatigue. The women describe themselves as stubborn persons and as persons who are engaged in too many tasks at the same time, despite their pain, because they have difficulties in setting limits for themselves and saying “No”. As an example, one woman said that her family had moved from one apartment to another and that she alone, despite her widespread pain and stiffness, moved all the furniture into one of the rooms during the day. This effort was done because she wanted to surprise her husband and show him that everything was already done when he returned from work. She ignored her pain sensations because she wanted to be appreciated by her husband as a “good girl”.

It was so great that we were moving and would sort of have something bigger with four rooms. It was fun to pick up our stuff but afterwards when you had landed and almost everything was in its place then it hit—I felt that I was in a lot of pain. I didn't take any breaks but went all out from seven o'clock in the morning to ten o'clock at night.

I was pushing myself very, very hard and was in a lot of pain. I could be sitting in the staff room and be in so much pain that tears were falling. So I wiped my tears and put on a smile, walked out and started working again.

That's something you won't hesitate doing (put on a mask) if you go outside, go to the store or go to parents’ evening and so on. So no matter how much pain you're in you put that mask on and if anyone asks how you're doing you answer “Good”. Who wants to hear you say that today you're in pain, the area between my shoulder blades is aching and my hip is hurting. Then they'll leave!

Discussion

Women with fibromyalgia are exposed to a psychologically high load in combination with intensive physical work, which seem to contribute to their experiences of pain, stiffness and fatigue. The women's need for recovery after carrying through with their physical work is not adequately satisfied. The interpretation of the narratives in our study is that the women as a group have had a tough childhood with unmet psychological needs, high demands and mental overload. The women stated that both during their childhood and as adults they have strived to be “good and responsible girls” and hoping that thereby be acknowledged and appreciated by people in their surroundings. As adult women they have high demands on themselves and are pushing themselves to do more than they can reasonably manage. The physiological mechanisms behind the initiation and the maintenance of longstanding pain, such as fibromyalgia, are still not fully known despite extensive research. The aim of this interview study was not to contribute to research on the origin of fibromyalgia. Rather the aim of this study was to gain a deeper understanding of what living with fibromyalgia means to afflicted women.

According to our data, the women's main concern is to reach a balance in daily life. The substantive theory, grounded in interview data from women with fibromyalgia, explains how this main concern is managed by strategies aimed at minimizing the dysfunctional interplay between activity and recovery (core category). Seven strategies, related to the core category, were emerging from the data and used by the women to reach a balance in daily life. These strategies are labelled avoiding unnecessary stress, utilizing good days, planning activities in advance, having to pay the price when allowing oneself too much activity, distracting oneself from pain, engaging in alleviating physical activities and ignoring pain sensations (see ).

Avoiding unnecessary stress, planning activities in advance and engaging in alleviating physical activities are all adequate and helpful strategies for minimizing stress, pain and fatigue in daily life. If these strategies are the dominating ways to manage daily life, the imbalance between activity and recovery should be minimized or reduced. Paying the price for allowing oneself too much activity is a strategy which seems to be necessary for maintaining social relations and quality in life. The women say that they cannot accept a life without social gatherings, parties, dancing and having fun together with friends. Despite their pain and the knowledge that the pain will be even worse the next day, they sometimes allow themselves to participate in social gatherings. Afterwards, they are forced to pay the price for having fun by experiencing one or more days with worsened pain, stiffness and fatigue. Social inclusion, well-being, and quality in life are given higher priority compared to experiencing as the lowest possible degree of pain. However, several studies have shown that fibromyalgia has a substantial negative impact on both social and occupational life (e.g., Arnold et al., Citation2008).

Distracting oneself from pain is an adaptive strategy which seems to contribute to periods of absence of pain. According to our data, it is obvious that diverting attention from the pain can contribute to a “pain gap”, i.e., a shorter or longer period of absence of pain. According to Henriksson (Citation2002) about one third of patients with fibromyalgia sometimes have “pain gaps”. When the women are doing something that captures their interest and engagement, it seems as if they become absorbed in what they are doing and forget their suffering. The pain is no longer at the front of their attention; rather it moves to the background and is no longer in their consciousness. The phenomenon to forget time and space, has similarities to the concept of “flow” (Csikszentmihaly & Rathunde, 1993) and can obviously lead to occasional absence of pain perception. Warmth, relaxation, massage, Chi Gong, dancing, joy and sexual intercourse were reported by the women in the study as preceding occasional absence of pain. According to our data, such “pain gaps” varied between lasting <1 h up to several days or months. This strategy, diverting attention, is possible to learn or improve in health promoting courses, based on principles of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), for patients with symptoms like for example longstanding pain and tinnitus.

The last strategy, ignoring pain sensations, mainly seems to be a maladaptive strategy in daily life. By ignoring pain, the women's fast pace and hyperactivity is maintained. This will probably result in increased pain and fatigue and thereby increase the imbalance between activity and recovery and work counter to reaching a balance in daily life. How can health care professionals support patients in coping with their fibromyalgia? Our results show that diverting attention from the pain can contribute to shorter or longer periods of absence of pain perception. Based on findings from our study we suggest health promoting courses based on the principle of CBT. Such a course can be offered in Primary Care and as a suggestion be led by registered nurses or psychologists, who are experienced in CBT and who have extensive knowledge about theories on longstanding pain, stress and coping. A critical review of controlled clinical trials (Kroenke & Swindle, Citation2000) has showed positive results from group therapy and interventions based on CBT (five sessions only) on patients with somatisation or symptom syndromes, such as fibromyalgia. CBT-treated patients improved significantly more than control subjects. Especially, the patients’ physical symptoms improved and the benefits of the treatment were sustained for up to 12 months. Also, Mortey, Eccleston and Williams (Citation1999) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of CBT and behavioural therapy for adult patients with chronic pain. They found that CBT produced significant greater changes for pain experiences, cognitive coping and appraisal (positive coping measure) and reduced behavioural expression of pain. They found no significant differences for mood/affect, catastrophizing (negative coping behaviour) or social role functioning. The researchers’ conclusion of this study was that psychological treatments based on CBT are effective. Recently, Bernardy, Fuber, Köllner and Winfried (2011) performed a systematic review with meta-analysis of the efficacy of CBT in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Randomized controlled trials comparing CBT to controls were analysed. They concluded that CBT improved coping with pain, reduced depressed mood and help-seeking behaviour in patients with fibromyalgia.

The conclusion from our study is that the main concern for women with fibromyalgia is their striving to reach a balance in daily life. This is done by minimizing the dysfunctional interplay between activity and recovery. Most strategies they are using, except ignoring pain sensations, can help to conserve energy, reduce stress, and to avoid repetitive motion. Distracting oneself from the pain seems to be a helpful strategy as it may lead to longer or shorter “pain gaps”. According to our data, when the women are doing something that really captures their engagement, they become absorbed in what they are doing and forget their suffering. The pain is no longer in the front of their awareness; rather it moves to the background and is no longer in their consciousness. This strategy, diverting attention, is possible to improve or learn by attending health promoting courses, based on principles of CBT, for patients with longstanding pain. We suggest that such courses are offered in primary care. The course can be led by registered nurses or psychologists, who are experienced in CBT and have extensive knowledge about theories on longstanding pain, stress and coping. This would increase well-being and quality in life for women suffering from fibromyalgia.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant to professor Lillemor R.-M. Hallberg, Halmstad University, Sweden from The Swedish Rheumatism Association (Reumatikerfonden) and The Social Insurance Agency, Halland County (Försäkringskassan i Halland). Thanks are also due to all the women who participated in the in-depth interviews and to psychologist/PhD Kerstin Wentz, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Sweden who conducted the interviews with women in subsample I.

References

- Arnold L. M. Crofford L. J. Mease P. J. Burgess S. M. Palmer S. C. Abetz L, et al.. Patient perspectives on the impact of fibromyalgia. Patient Education and Counseling. 2008; 73: 114–120.

- Bernardy, K., Fuber, N., Köllner, V., & Häuser W. (2010). Therapies in Fibromyalgia syndrome. A systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. The Journal of Rheumatology. Retrieved July 29, 2010, 10.3402/qhw.v6i2.7057.

- Blumer D. Heilbronn M. Chronic pain as a variant of depressive disease. The pain-prone disorder. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1982; 170: 381–406.

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage. London, 2006

- Corbin J. Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research. Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory3rd ed. Sage. Thousand Oaks CA, 2008

- Csikszentmihalyi M. Rathunde K. The measurement of flow in everyday life: Towards a theory of emergent motivation. Developmental perspectives on motivation. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation. Jacobs J. E. University of Nebraska Press. Lincoln, 1993; 60.

- Glaser B. Basics of grounded theory analysis: Emergence vs forcing. Sociology Press. Mill Valley CA, 1992

- Glaser B. Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine. Chicago, 1967

- Glaser B. G. The Grounded Theory Perspective II: Description's remodeling of grounded theory. Sociology Press. Mill Valley California, 2003

- Hallberg L. R. M. Carlsson S. G. Psychosocial vulnerability and maintaining forces related to fibromyalgia. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 1998a; 12(2): 95–103.

- Hallberg L. R. M. Carlsson S. Anxiety and coping in patients with chronic work-related muscular pain and patients with fibromyalgia. European Journal of Pain. 1998b; 2: 309–319.

- Hallberg L. R. M. Carlsson S. G. Coping with fibromyalgia. A qualitative study. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2000; 14: 29–36.

- Hallberg L. R. M. The “core category” of grounded theory: Making constant comparisons. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being. 2006; 1: 141–148.

- Henriksson K. G. Is fibromyalgia a central pain state?. Journal of Musculoskeletal Pain. 2002; 10: 45–57.

- Henriksson C. Carlsberg U. Kjällman M. Lundberg G. Henriksson K. G. Evaluation of four outpatient educational programmes for patients with longstanding fibromyalgia. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2004; 36(5): 211–219.

- Jensen K. Brain mechanisms in pain regulation. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Karolinska Institute, Sweden. 2009

- Kroenke K. Swindle R. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for somatization and symptom syndromes: A critical review of controlled clinical trials. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2000; 69: 205–215.

- Lazarus R. S. Folkman S. Coping and adaptation. Handbook in behavioural medicine. Gentry W. D. Guilford Press. New York, 1984; 282–325.

- Mortey S. Eccleston C. Williams A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive behavior therapy and behavior therapy for chronic pain in adults, excluding headache. Pain. 1999; 80: 1–13.

- Neumann L. Buskila D. Epidemiology of fibromyalgia. Current Pain Headache Report. 2003; 7(5): 362–368.

- Nicassio P. M. Radojevic V. Schoenfeld-Smith K. Dwyer K. The contribution of family cohesion and the pain-coping process to depressive symptoms in fibromyalgia. Annual Behavioural Medicine. 1995; 17: 349–356.

- Nielson W. R. Jensen M. P. Hill M. L. An activity pacing scale for the chronic pain coping inventory: development in a sample of patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Pain. 2001; 89: 111–115.

- Plummer K. Documents of life 2. An invitation to a critical humanism. Sage. Thousands Oaks CA, 2001

- Schaefer K. M. The lived experience of fibromyalgia in African American women. Holistic Nursing Practice. 2005; 19: 17–25.

- SFS. (2003). Lag om etikprövning av forskning som avser människor. (No. 460)[Law about ethical approval of research on human beings]. The Swedish Parliament (Näringsdepartementet).

- Söderberg S. Lundman B. Transitions experienced by women with fibromyalgia. Health Care for Women International. 2001; 22: 617–631.

- Söderberg S. Lundman B. Norberg A. The meaning of fatigue and tiredness by women with fibromyalgia and healthy women. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2002; 11: 247–255.

- Wentz K. A. H. Lindberg C. &Hallberg L. R. M. Psychological functioning in women with fibromyalgia. A grounded theory study. Health Care for Women International. 2004; 25(8): 702–729.

- Wolfe F. Clauw D. J. Fitzcharles M. A. Goldenberg D. L. Katz R. S. Mease P, et al.. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Research (Hoboken). 2010; 62(5): 600–610.

- Wolfe F. Smythe H. A. Yunus M. B. Bennet R. Bombardier C. Goldenberg D. L. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1990; 33(2): 160–172.

- Wyalonis G. W. Heck W. Fibromyalgia syndrome. New associations. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1992; 71(6): 345–347.