Abstract

The aim of this paper is to discuss the development of a cultural care framework that seeks to inform and embrace the philosophical ideals of caring science. Following a review of the literature that identified a lack of evidence of an explicit relationship between caring science and cultural care, a number of well-established transcultural care frameworks were reviewed. Our purpose was to select one that would resonate with underpinning philosophical values of caring science and that drew on criteria generated by the European Academy of Caring Science members. A modified framework based on the work of Giger and Davidhizar was developed as it embraced many of the values such as humanism that are core to caring science practice. The proposed caring science framework integrates determinants of cultural lifeworld-led care and seeks to provide clear directions for humanizing the care of individuals. The framework is offered to open up debate and act as a platform for further academic enquiry.

Providing health care that is respectful, thoughtful, compassionate, holistic and individualized is arguably central to the patient experience. Such an approach needs to be core to all caring practices particularly with society becoming increasingly culturally diverse. This is evident, for instance with the European Union's active promotion of free movement of citizens across its member countries, which has been a positive strategy at a political, social and economic level. Indeed, debates around cultural care may equally apply to individuals who share common identities within nation states and for whom physical migration across nation-states is not relevant.

However, international statistics confirm that when individuals migrate to a new country, they may experience higher rates of morbidity and mortality when compared with indigenous populations as existing health care systems fail to address the needs of such groups (De Souza, Citation2008; Domenig, Citation2004 Citation2007; Duke, Connor, & McEldowney, Citation2009). This is often attributed to language barriers, expectations, economic factors, and knowledge of the local health care system. With the increased levels of migration and immigration globally, many immigrants/refugees and their families who suffer from health and emotional problems present opportunities to review the skills health care providers offer in the development of transcultural care (Domenig, Citation2007; Jenko & Moffitt, Citation2006).

Additionally, the mass migration of nurses and other health professionals has become commonplace across Europe, mirroring the situation in the USA (Domenig, Citation2007; Hancock, Citation2008). Reasons for this are linked to seeking improved pay and better working and living conditions. A consequence of this increase in non-native health care practitioners caring for indigenous and non-indigenous communities is that those delivering and receiving care are challenged in providing high quality care within the existing health care systems. The challenges raised by the free movement of populations provide an opportunity to consider the philosophy underpinning caring and culture as well as the implication for the discipline of caring science. The aim of this paper is, therefore, to discuss the development of a cultural care model that seeks to inform and embrace the values of caring science and develop a new framework for cultural care.

Background

To contextualize the discussion, the paper begins by introducing the varying concepts of caring with particular attention to the discipline of caring science. The paper then discusses the literature on culture and care and its implications for practice. The section concludes by considering the relationship between culture and caring science.

Caring

If the central role of health care professionals is to effectively engage and support patients and families in a meaningful, person–centered, and therapeutic manner that embraces the richness of human diversity, the notion of individualized caring is pivotal.

While there are many approaches to caring that remain contested in the literature (Eriksson, Citation1997; Morse, Solberg, Neander, Bottorff, & Johnson, Citation1990; Paley, Citation2001, Watson & Smith, Citation2002), a European perspective of caring science, although relatively new, offers a distinctive outlook that is situated in the Western, liberal, individualist traditions (Eriksson, Citation1992; Gustafson, Citation2005). The strand of Scandinavian caring science has strong epistemological and ontological roots that are humanistic and undeniably spiritual, focusing on caring as caritas (love and charity), suffering, well-being, patience, sacrifice and healing (Ekebergh, Citation2009; Eriksson, Citation2002). Within these traditions, the aims of caring are generally agreed to be alleviating patient suffering and promoting the health and well-being of individuals (health as having, health as being, and health as becoming) (Eriksson, Citation1992). Respect, sensitivity and empathy are inherent in this approach to care and are values deeply embedded in a Christian European tradition (Gustafson, Citation2005).

Recently, many (for example, Dahlberg, Citation2006, Dahlberg, Dahlberg, & Nystrom, Citation2008; Ekebergh, Citation2007 Citation2009), have drawn attention to a lifeworld existential perspective, focusing on a more person-centered approach to care. It is this perspective of caring science that underpins this paper. From the foundations of Eriksson (Citation2002), contemporary perspectives on caring science assume a more philosophical and humanistic approach diverging from the centrality of the religious orientation. Caring science is thus deemed to require the complex integration of humanly sensitive care that includes:

A particular view of the person.

A unique perspective of evidence that can guide caring.

A particular view of care that is lifeworld led and consequently, by its very nature holistic (Galvin, Citation2010,p. 169).

In essence, the underpinning and guiding values are that practices, which are shaped by perspectives such as these, may be vital in humanizing the routine use of technical, procedural, and instrumental knowledge in many clinical settings.

Culture and its implications for practice

Culture is acknowledged as one of the most complicated and continually evolving concepts in the English language (Williams, Citation1983). As a contested term, there is no one definition of culture. However, most definitions focus on the learned, shared values, traditions and beliefs of a group; that culture is part of the patterned behaviour of a particular group (Goody, Citation1994). Current debates emphasize culture as a process, rather than a static entity and highlight differences and similarities both within and across cultures (Culley, Citation2006; Kleinman & Benson, Citation2006). Culture, therefore, is understood as that which aggregates individuals and processes, it is not something sui generis (a social fact existing outside the minds of individuals) or that which overly determines people's lives and neglects individual agency. As a process, culture is open-ended, dynamic and fluid. Within health care, it is accepted that culture has a vital impact on health and illness beliefs, health practices and care (Helman, Citation2007).

With the commitment of nursing to enhance patient care globally, a number of frameworks and models have been developed to promote cultural care. Together, these have been considered by the American Academy of Nursing and the Transcultural Nursing Society to develop standards of practice for “culturally competent care” that, they suggest, are universally applicable (Douglas et al., Citation2009). However, cultural competence and transcultural care is not without its critics. Many of the well-known transcultural theories (Andrews & Boyle, Citation2002; Campinha-Bacote, Citation1999, Citation2002, Citation2005, Citation2008; Leininger, Citation1982, Citation1991, Citation1994, Citation1995, Citation2002; Polaschek, Citation1998; Purnell, Citation2002; Ramsden, Citation1992) refer to cultural groups primarily in terms of ethnicity. This results in a rather narrow, essentialist and limiting view of culture, as opposed to the more fluid constructionist view espoused above; it defines patients and clients as “the other” in opposition to the “non other” society and care giver. Leininger's assertion that her Theory of Cultural Care Diversity and Universality “was a great breakthrough in caring for the culturally different” (our italics) (Leininger, Citation2002) epitomizes this discourse.

This emphasis on ethnicity and “foreignness”, can be seen throughout much of the transcultural caring literature. Gebru and Willman (Citation2003) and Perget, Ekblad, Enskar, and Bjork (Citation2008) have argued that the rise in interest in transcultural caring in Sweden is being generated by the increasingly multi-cultural nature of Swedish society. A justification that we, in fact, have made in the introduction to this paper. Perceived threats to the nation and the “supposedly homogeneous society” are dominant within transcultural theory (Gustafson, Citation2005). A further difficulty inherent with definitions of culture based on ethnicity is that ethnicity itself becomes problematized and even pathologized. “Acceptable” cultural practices are “preserved and maintained” (labelled as “traditional”); however, those deemed “unacceptable” are in need of “accommodation, negotiation, repatterning or restructuring” (Leininger, Citation2002). Although all transcultural theories emphasize cultural understanding and acceptance, such practices highlight the enactment of a dominant discourse that privileges one form of knowledge, behaviour and culture, over another.

A useful challenge to the narrowly ethnic focus of much of the traditional transcultural literature can be made by its application to “cultures” constructed by gender, sexuality, economic differences, class, (dis)ability and age. Viewing these constructs through a cultural lens, not only illuminates the complexities of culture but also assists in the realization that culture does not merely relate to “ethnicity”. Culturally competent care, if accepted as an achievable and appropriate aim, is then taken as an aim for all care situations and not just those deemed as relating to “the other”. This approach also assists in challenging and breaking down cultural stereotypes and highlights the similarities, differences and borderlands within and across cultures.

Although congruent with the underling liberal philosophy of the caring sciences, transcultural caring, by focusing on individual cultures and the uniqueness of the patient/client, is arguably apolitical and ahistorical. The impact on identity, culture and health by unequal power relations, oppression and a history of exploitation and colonialism is largely ignored by a transcultural approach to caring. Farmer (Citation2005) would add structural violence to this critique, in that the issue of who falls ill and who is given access to “care”, as it is cultural defined, is influenced by racial, gender and other inequalities and cultural prejudice. A danger of such approaches to care is that racism and oppression are hidden and in fact perpetuated, thus re-inscribing the dominant social discourses (Gustafson, Citation2005). One exception to this approach is Ramsden's (1992) cultural safety model that has at its core, a focus on inequality, racism and discrimination. Interestingly, this model also highlights the diversity and plurality within cultures such as the differences between rich and poor, young and old and urban and rural (Popps & Ramsden, Citation1996). Alternative approaches are emerging, for example the “Explanatory Model” (Kleinman & Benson Citation2006) focuses on what “really matters to the patient” and “Insurgent Multiculturalism” (Giroux, Citation1994; Wear, Citation2003) that plays down the focus on non-dominant (ethnic) groups and questions the social construction of dominance and inequality.

Attracted by the need to bring clarity on the extent to which cultural care is explicit within caring science position particularly in the context of increased human migration across Europe, academic colleagues from a number of universities in England, Sweden, Norway and Denmark, as members of the European Academy of Caring Science (EACS), began to collaborate to address this issue.

Methodological approach

The methodology in developing the proposed cultural caring model took a staged approach, with the findings of each phase guiding further scholarly thinking as listed below:

Literature review.

Collaborative inquiry.

Review of cultural care models.

Development of outline framework of cultural care for caring science.

Literature review

To articulate the way in which caring science communicated cultural care delivery, a critical review of the literature was conducted as an initial aim. Our purpose was to determine the manner in which a European dimension of caring science dealt with cultural care aspects. Two specific sub-questions informed the inquiry:

What is the relationship between caring science and cultural care?

To what extent has cultural caring been embraced, communicated and critically assessed within caring science literature?

A systematic search for scholarly papers articulating European core concepts of caring science(s), from 1998 to the present day 2010, was conducted. Specifically, papers with “caring science(s)” in the title and reflecting a European perspective were eligible for inclusion and analysis. Additional criteria included that selected papers should be available in English or Scandinavian languages.

Analysis

While ideally, reviewed editorials are not sufficiently robust sources for analysis of issues under inquiry, the identified material at one level signals the importance of the subject in the related discipline, whereas at another level it does also give a sense of the absence of high- quality literature in the field. For this exercise, all papers accessed were thematically analysed for evidence of how caring science(s) embraced either trans, inter-, or cross-cultural care and how this is articulated in a practical way. The papers were reviewed by members of the team (JWA, ER and LU) and any discrepancies were resolved until consensus was reached.

Results

Our bibliographic database search yielded a total of 34 sources that included editorials, studies and book reviews. Of these, only 22 papers met our criteria and these were published in eight journals namely the Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science, Nursing Science Quarterly, Nursing in Critical Care, Qualitative Health Research, Nordic Journal of Nursing Research & Clinical Studies/Vård i Norden, International Journal of Nursing Studies, International Journal of Qualitative Methods and Journal of Nursing Management. summarizes the range of issues addressed within the papers and these have been clustered into three types of outputs.

Table I. Summary of content covered by the 22 papers reviewed.

Generally, the papers addressed conceptual and philosophical analyses associated with caring science and lifeworld, whereas others engaged in exploring how to take caring science as a discipline forward. A small number of empirical works demonstrate the application of caring science ideals to practice and the human experience (see ). However, in this cross European selection of papers, there was clear evidence of how cultural care was not communicated within the caring science(s) literature, and this can be regarded as an important finding.

Discussion

As previously stated, caring science aims to develop knowledge and research that better understands the human condition and, so it needs to broaden its scope and be open to the wider health care professions that contribute to improving the human condition for patients (Eriksson, Citation2002 Eriksson, Citation2010; Lomborg, Citation2005).

Although it might be assumed that there is a clear link between caring science and culture, particularly in terms of the promotion of theories and frameworks or models of caring practice, this was not overt in the current analysis. Not one of the 22 papers reviewed related to caring science(s) made any explicit reference to the concept of culture and its influence on caring science. There may well be a tacit assumption that the cultural aspects of caring are central and integral to the philosophical values and beliefs underpinning caring science forming part of a humanist, holistic and spiritual endeavour.

As acknowledged previously, we know from the wider global literature that ethnic minority groups who emigrate from their country of origin experience higher rates of morbidity and mortality when compared with indigenous populations (De Souza, 2008). Additionally, migrants/refugees suffering from health and emotional problems present opportunities for health professionals to create a new way of thinking to support them (Albarran, Fitzpratrick, Clarke, & Phillipa-Walsh, Citation2000; Domenig, Citation2007; Jenko & Moffitt, Citation2006; Searight & Gafford, Citation2005).

A framework of care that embraces culture as integral to its value system may be deemed important when considering the current infrastructure being developed within the European Community that aspires, by 2014, to the free movement and employment of its people (Citizens Information, Citation2011; Geddes, Citation2003). However, within Caring Science, there is a lack of guidance for practitioners on how to support the individual's needs that embrace the cultural and diverse characteristics that shape the lifeworld of human beings. Moreover, with the current trends in the cultural heterogeneity of society, it would seem timely for a caring science to articulate the cultural dimension more explicitly.

Developing a way forward

In response to the findings of the reviewed literature, we were curious to identify whether a cultural model existed that embraced caring science values to potentially facilitate its adoption. Criteria for the selection of a framework (see below) were informed by discussions and ideas emerging from a meeting with the wider membership of the EACS in Växjö, Sweden, in 2008. Members representing the EACS constituency, which included individuals with diverse academic and clinical experiences, were invited to explore links between caring science and cultural care under specific constructs about persons, for example internal, external, geographical and influencing factors (see ). These constructs and related elements that arose from the contributions of group members aimed to capture the relationship between caring science and cultural care. In our discussions, we were particularly mindful that different socio-political contexts (shape internal cultural beliefs, for example, democratic vs. authoritarian attitudes) vary from permitting open critique to total subservience. Indeed, addressing attitudes to authority are relevant and influential when considering multi-cultural team work

Table II. Constructs linking caring science and cultural care (EACS 2008).

Criteria identified by EACS for selection of cultural model:

There must be congruence with caring science values and beliefs that:

Acknowledge a particular view of people (spirit, religion).

Demonstrate a unique outlook on evidence base to guide caring.

Offer a distinctive focus on care that is lifeworld led and consequently, by its very nature, holistic.

Illuminate the centrality of caring and trusting relationships and partnerships that are integral in the caring experience.

Offer an interdisciplinary approach to caring.

Conceptually relevant to modern health care and have been empirically validated.

Have a broad international appeal.

Have intuitive appeal and practical simplicity.

Subsequently, the group critically reviewed a range of published models of cultural care, with the aim of identifying a framework to guide practice. A number of models were examined including Campinha-Bacote (Citation2002), Gebru and Willman (Citation2003), Leininger (Citation2002), Narayanasamy (Citation2002), Purnell (Citation2002) and Wikberg and Eriksson Citation2008. Each was noted to offer a unique approach to assist practitioners, mainly nurses in providing culturally sensitive and competent care. However, the Transcultural Assessment Model (Giger & Davidhizar, Citation2004) had immediate appeal in that it addressed many of the listed criteria and has been reported to sensitively respond to the rapidly changing demographics within the US population. With much of its work related to supporting the needs and experiences of immigrants across the USA, the model may help in understanding of the issues experienced by large number of people emigrating within Europe. It was anticipated that such a model might pave the way to a closer relationship between culture and the caring science ideology, and, as Kleinman and Benson (Citation2006) suggest, find out what really matters to the individual. Giger and Davidhizar's (Citation2004) model may also be useful in re-conceptualizing culture by defining it not only in terms of ethnicity but also by illuminating other equally relevant cultural identities such as age and sexuality.

Transcultural assessment model

This model (Giger & Davidhizar, Citation2004) offers an inclusive approach to addressing cultural issues and it integrates family perspectives in a holistic manner (Jenko & Moffitt, Citation2006). Moreover, it has been used with a range of culturally different groups, mainly a large number of groups from around the globe who have migrated to the USA (Giger & Davidhizar, Citation2004). However, an obvious reason for adopting this model was the shared synergy with the core dimensions of the lifeworld, a core dimension of the EACS and the assessment of need and caring practices. The model also reflects a synergy with religion and spirituality, the nature and scope of relationships and caring motivations. It recognizes the danger of stereotyping and of making assumptions about individuals within groups, which can lead to erroneous interpretations and judgements (Giger & Davidhizar, Citation2004).

Although the model is designed for use by nurses, it is flexible enough to offer an inclusive approach to addressing cultural issues for the individual cared for by a range of health and social care professionals. As with other models reviewed, Giger and Davidhizar (Citation2004) equally support the notion of partnership working with patients/clients as key to its success.

According to Giger and Davidhizar (Citation2004, p. 3): “Culture is a patterned behavioural response that develops over time as a result of imprinting the mind through social and religious structures and intellectual and artistic manifestations. Culture is also … affected by internal and external environmental stimuli”.

This transcultural assessment model values the uniqueness of the individual. It also values the environment within which care is being provided, to be culturally sensitive to the needs of the individual. Whilst developed by nurses, and for nurses, it recognizes its application to other disciplines and through research it is being refined and enhanced to establish its validity and reliability with different population groups and in different settings (Giger & Davidhizar, Citation2004).

The model consists of six cultural phenomena, each of which they recommend should be assessed when working with patients/service users to identify their cultural uniqueness (Citation2002, 2004, p. 17). The following represents the six cultural phenomena:

Communication (the means of transmitting and preserving individual's culture. Embraces the whole world of human interaction).

Space (refers to respecting each individual's personal distance/zone within which they interact and will vary depending on culture and familiarity with the individual. In the clinical setting, a positive therapeutic relationship is dependent on respect and sensitivity to each patient's personal space).

Social organization (this is about family, tribe, social networks, religious beliefs and affiliations)

Time (relates to cultural orientation of time, such as the past, present and future).

Environmental control (this is the ability of the individual to plan and control factors in the environment that affect them. If individuals perceive a lack of control, they are less likely to engage in activities that may improve their health and have a fatalistic attitude to their situation).

Biological variations (this applies to aspects such as growth, development and diseases as experienced by different racial groups, which may be influenced by dietary factors or genetic profiles).

Giger and Davidhizar (Citation2004) suggest that these concepts, borrowed from biomedical and social science disciplines, can enable practitioners to understand their patient's cultural perspective and the impact each has on their health. As previously explored, the philosophical foundation of a more humanized form of care in the notion of lifeworld-led care embodies these same principles (Galvin, Citation2010; Todres, Galvin, & Dahlberg, Citation2006). Lifeworld-led care embraces a holistic quality which brings together an understanding of meaningful relationships within that lifeworld. Proponents of lifeworld-led care refer to five constituents as follows:

Temporality (humanly experienced time, rather than “tick-tock” time).

Spaciality (world of places and things that have meaning to living).

Inter-subjectivity (refers to how we are in the world with others).

Embodiment (refers to the lived body—how we live in meaningful ways in relation to the world and others).

Mood/emotional attunement (is about perceptual and interactive emotion thatinfluences the other dimensions).

It was this valuing of the individual and their experience of the lifeworld that highlighted the obvious connection with Giger and Davidhizar's (Citation2004) cultural assessment model. At this point, we felt empowered to adapt and shape this model by bringing together our own experiences, the outcome of our seminar at Växjö and the underpinning values of a lifeworld-led approach to care.

Determinants of cultural lifeworld-led care

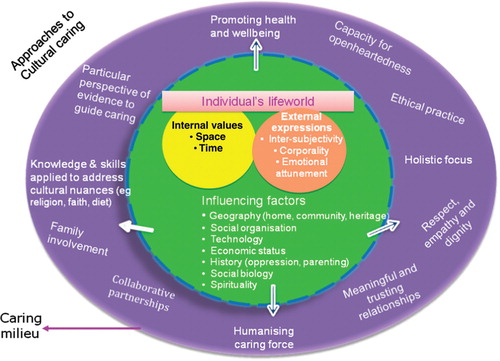

represents our conceptual framework that was strongly influenced by the need to value the individuality of the person being cared for through the lens of a lifeworld-led perspective. Firmly, at the heart of the framework are the two inner circles that represent the lifeworld-led dimensions that need to be considered when organizing and implementing sensitive person-centered care. As advocated by Kleinman and Benson (Citation2006), this part of the framework would help the caring professionals get to the heart of what is important to the person and their family. The five lifeworld dimensions can be grouped under the notion of internal values (including Space and Time) and external expression, namely: inter-subjectivity (relationality), embodiment (corporality) and emotional attunement. In a world where patients/service users are becoming firmly placed as central to the decision-making process around desired outcomes and delivery of health care (Todres et al., Citation2006), the need to articulate a clear direction for the health care professional is crucial for its success. A framework of care that focuses on the humanizing values encourages health care professionals to address the particular needs of the person. Caring science has at its heart the core values of humanization and remains true to the needs of the individual whatever the individual's culture, creed or orientation.

The proposed framework recognizes the numerous influencing factors impinging on the individual's lifeworld as can be seen in the larger broken circle surrounding the two inner circles. These influencing factors include geography (the person's home, community and heritage), social organization, economic status, history (e.g., oppression, parenting), social biology and also the person's spirituality. This framework equally acknowledges the fluidity of experiences of the individual and the influencing factors, continually shaping and modifying how the individual feels, interacts and responds to both the outside world affecting his well-being and his inner mental, physical, emotional and spiritual health.

The principles informing and guiding the professional caregiver are then identified in the outer circle. As the infrastructure supporting the registered professional health carer develops (Department of Health & Skills for Health, Citation2004), the demands and expectations made of the professional are ever increasing. As the field of biomedical science extends its boundaries of knowledge, so the non-medical health care professionals are challenged to support their knowledge and decision making in practice with a greater expertise and understanding of the options and evidence (choices) for care. Inter-professional working is vital to ensure that services are harnessed in a coherent way to support the needs of the individual and their families through their episode of ill health. Understanding the philosophical and practical aspects of the needs of the individual and their cultural nuances encourages a humanized approach to care within a caring science perspective.

Throughout this framework, the boundaries between all the circles are broken, allowing a two-way process of partnership. As the patient's condition improves or deteriorates, so the health care professional harnesses the individual's expertise, resources and holistic understanding of the situation to respond in a meaningful and openhearted (Galvin & Todres, Citation2009) way to support the inner well-being of the individual. The framework is all embracing. It begins to offer a comprehensive guide to direct the professional towards recognizing and respecting the core values of humanization, whilst at the same time working in partnership with the patients to better understand the nuances of their cultural beliefs.

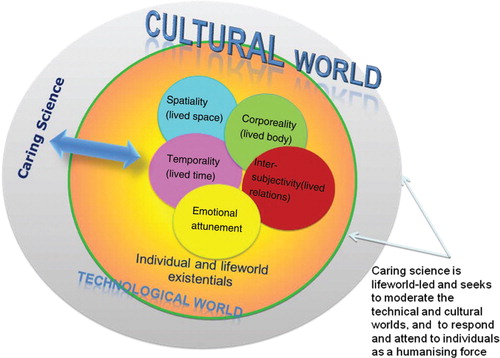

provides a microperspective by focusing on the two inner circles of the lifeworld dimensions. Assessment of the five dimensions of the lifeworld enables health care professionals understand how patients are directly influenced by the technological, cultural, religious and spiritual world around them. The increased movement of people across Europe, as promoted by the EU (Citizens Information, 2011, Geddes, Citation2003), has significantly impacted on the health care workforce both in terms of language and in the philosophy underpinning the caring process. As caring science evolves, the nature of caring practices increases, so the anticipation of fulfilling the needs of the individual can become a reality, wherever the caring activities occur.

This conceptual framework recognizes the complexities of caring and, through a cultural lens, it aims to assist the realization, recognized by Kleinman and Benson (Citation2006, p. 1673) that culture is not “homogenous or static” and does not merely relate to “ethnicity” or “foreignness” but reflects a wider understanding of the needs of the individual from “cultures” constructed by gender, sexuality, economic differences, class, (dis)ability and age. Additionally, the work of Crenshaw (Citation2002) outlines the notion of “intersectionality” that recognizes the multiple dimensions of culture, and describes how race and gender intersect affecting the quality of life and arguably the health care, for many people around the world.

The framework presented here offers a platform to guide, inspire and facilitate health providers to focus their endeavours on promoting humanistic care that embraces partnership, respect, dignity and understanding of the individual's lifeworld in their various contexts. This position enables practitioners to look beyond individual differences of people (including gender, age, class and ethnic origin) and concentrate in celebrating their uniqueness by providing sensitive, thoughtful and intelligent person-centered care. According to Kleinman and Benson (Citation2006), this process begins by having genuine interest in the person, not as a case study or a clinical condition, and asking “what really matters most to you in terms of your health and treatment”.

Conclusion

This paper represents a journey of exploration for members of the EACS to find a link between cultural care and caring science. Our initial review identified a paucity of available literature explicitly articulating how care for different cultural groups in the context of caring science was organized. This prompted a series of inquiries aimed at exploring the relationship between cultural care and a caring science ideology.

Part of the challenge in progressing our thinking was related to exploring the wider, and often complex, debates associated with culture and how the concept affects care giving. A further challenge to the group was to identify whether a transcultural model existed that could interface with the lifeworld values associated with caring science approach.

The cultural assessment model by Giger and Davidhizar (Citation2004) offers synergy with the core dimensions of the individual's lifeworld, inclusivity involving family and significant others and a practicality, allowing caring science disciplines to focus on the humanity of individuals in their clinical assessment. The proposed hybrid framework highlights how individuals interpret experience and respond to health and ill health; it focuses on shared human characteristics and encourages care that is humanizing, dignified and respectful of individuals. Additionally, the lifeworld perspective will provide clear directions for care, and help with descriptions and experiences relevant to caring (Galvin, Citation2010). Ultimately, it is viewing the individual and their health priorities that matter most which is the key

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study.

References

- Albarran, J. W, Fitzpratrick, J., Clarke, B., & Phillipa-Walsh, G. (2000). Access to sexual health services for sub-Saharan communities in Avon. England: Faculty of health and social care, University of the West of England, Bristol: ISBN 86043 304 9.

- Andrews M. M. Boyle J. S. Trans-cultural concepts in nursing care. Journal of Trans-cultural Nursing. 2002; 13(3): 178–180.

- Asp M. Fagerberg I. Developing concepts in caring science based on a lifeworld perspective. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2005; 4(2): 57–67.

- Bergbom, I. (2010). Methodological research and research about methods in caring sciences. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. , 24, (Suppl. 1): 1.

- Bernspang B. The scope of the Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences (editorial). Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 1998; 12: 129–130.

- Bjorn A. Caring sciences. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 1999; 13(1): 1–2.

- Bjorn A. Caring sciences. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2003; 17(1): 1–2.

- Campinha-Bacote J. A model and instrument for addressing cultural competence in health care. Journal of Nursing Education. 1999; 38(5): 203–207.

- Campinha-Bacote J. The process of cultural competence in the delivery of health care services: A model of care. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2002; 13(3): 181–184.

- Campinha-Bacote J. A biblically-based model of cultural competence. Journal of Multicultural Nursing & Health. 2005; 11(2): 16–22.

- Campinha-Bacote J. People of African-American heritage. Transcultural health care: A culturally competent approach3rd ed. Purnell L. Paulanka B. F.A. Davis. Philadelphia, 2008

- Citizens Information., (2011). Freedom of movement in the EU. Retrieved October 5, 2011, from http:\\www.citizensinformation.ie/en/moving_country/moving_country/moving_abroad/freedom_of_movement_in_the_eu.html last updated 15. 7. 11.

- Crenshaw K. Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics and violence against women of colour. Identities. Alcoff L. Mendieta E. Blackwell Publishers. New York, 2002; 175–200.

- Culley L. Transcending transculturalism? Race, ethnicity and health-care. Nursing Inquiry. 2006; 13(3): 144–153.

- Dahlberg K. The essence of essences – the search for meaning structures in phenomenological analysis of lifeworld phenomena. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being. 2006; 1(1): 11–19.

- Dahlberg K. Dahlberg H. Nystrom M. Reflective lifeworld research2nd ed. Studentlitteratur. Lund, 2008

- Department of Health & Skills for Health., (2004). Key elements of the career framework. Retrieved December 23, 2010, from http://www.skillsforhealth.org.uk/careerframework.

- De Souza R. Wellness for all: The possibilities of cultural safety and cultural competence in New Zealand. Journal of Research in Nursing. 2008; 13: 125–135.

- Domenig D. Transcultural change: A challenge for the public health system. Applied Nursing Research. 2004; 17(3): 213–216.

- Domenig D. Transcultural competence in the Swiss health care system. Foundation Regenboog AMOC. Netherlands, 2007

- Douglas M. K. Pierce J. U. Rosenkeotter M. Callister L. C. Hattar-Pollara M. Lauderdale J, et al.. Standards of practice for culturally competent nursing care: A request for comments. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2009; 20(3): 257–269.

- Duke J. Connor M. McEldowney R. Becoming a culturally competent health practitioner in the delivery of culturally safe care: A process oriented approach. Journal of Cultural Diversity. 2009; 16(2): 40–49.

- Ekebergh M. Lifeworld-based reflection and learning: A contribution to the reflective practice in nursing and nursing education. Reflective Practice. 2007; 8(3): 331–343.

- Ekebergh M. Developing a didactic method that emphasises lifeworld as a basis for learning. Reflective Practice. 2009; 10(1): 51–63.

- Eriksson K. Different forms of caring communion. Nursing Science Quarterly. 1992; 5(2): 93.

- Eriksson K. Caring, spirituality and suffering. Caring from the heart: The convergence of caring and spirituality. Roach S. Paulist Press. New York, 1997; 68–64.

- Eriksson K. Caring science in a new key. Nursing Science Quarterly. 2002; 15(1): 61–65.

- Eriksson, K. (2010). Concept determination as part of the development of knowledge in caring science. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. , 24 (Suppl. 1), 2–11.

- Eriksson K. Naden D. Bjorn A. The silver anniversary of the Nordic College of Caring Science. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2006; 20(1): 1.

- Fagerstrom L. Engberg I. B. Measuring the unmeasurable: A caring science perspective on patient classification. Journal of Nursing Management. 1998; 6(3): 165–172.

- Farmer P. Pathologies of power: Health, human rights, and the new war on the poor. University of California Press. Berkeley, 2005

- Galvin K. Emami A. Dahlberg K. Bach S. Ekebergh M. Rosser E, et al.. Challenges for future caring science research: A response to Hallberg. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2006; 45(6): 971–974.

- Galvin K. T. Revisiting caring science: Some integrative ideas for the ‘head, hand and heart’ of critical care nursing practice. Nursing in Critical Care. 2010; 15(4): 168–175.

- Galvin K. T. Todres L. Embodying nursing openheartedness: An existential perspective. Journal of Holistic Nursing. 2009; 27: 141–149.

- Gebru K. Willman A. A research based didactic model for education to promote culturally competent nursing care in Sweden. Journal of Trans cultural Nursing. 2003; 14(1): 55–61.

- Geddes A. The politics of migration and immigration in Europe. Sage. London, 2003

- Giger J. N. Davidhizar R. E. Giger and Davidhizar transcultural assessment model. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2002; 13(3): 185–188.

- Giger J. N. Davidhizar R. E. Transcultural nursing: Assessment and intervention4th ed. Mosby. St Louis, 2004

- Giroux H. A. Insurgent multiculturalism and the promise of pedagogy. Multiculturalism: A Critical Reader. Goldberg LBlackwell. Oxford, 1994; 325–343.

- Goody J. Culture and its boundaries. Assessing cultural anthropology. Borofsky R. McGraw Hill. New York, 1994; 250–260.

- Gustafson D. Transcultural nursing theory. Advances in Nursing Science. 2005; 28(1): 2–16.

- Hall E.O.C. New initiatives in the Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2007; 21(3): 289–290.

- Hancock P. K. Nurse migration: The effects on nursing education. International Nursing Review. 2008; 55(3): 258–264.

- Helman C. G. Culture, health and illness. Hodder Arnold. London, 2007

- Isovaara S. Arman M. Rehnsfeldt A. Family suffering related to war experiences: An interpretative synopsis review of the literature from a caring science perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science. 2006; 20: 241–250.

- Jenko M. Moffitt S. R. Transcultural nursing principles: An application to hospice Care. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing. 2006; 8(3): 172–180.

- Jonsdottir H. The course ahead in caring sciences (editorial). Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 1998; 12: 65–66.

- Kirkevold M. Qualitative methods in the caring sciences: Time for critical reflection and dialogue (editorial). Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science. 2000; 14: 1–2.

- Kleinman A. Benson P. Anthropology in the clinic: The problem of cultural competency and how to fix it. PloS Medicine. 2006; 3(10): 1673–1676.

- Leininger M. Trans cultural nursing: Concepts, theories and practices. Wiley. New York, 1982

- Leininger M. Culture care diversity & universality: A theory of nursing. National League for Nursing Press. New York, 1991

- Leininger M. Transcultural nursing education: A worldwide imperative. Nursing & Health Care. 1994; 15(5): 254–257.

- Leininger M. Transcultural nursing: Concepts, theories, research and practices2nd ed. McGraw-Hill. New York, 1995

- Leininger M. Culture care theory: A major contribution to advance transcultural nursing knowledge and practices. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2002; 13(3): 189–192.

- Lindholm L. Nieminen A. Makela C. Rantanen-Siljamaki S. Clinical application research: A hermeneutical approach to the appropriation of caring science. Qualitative Health Research. 2006; 16(1): 137–150.

- Lomborg K. Useful research in caring sciences?. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2005; 19: 301–302.

- Lomborg K. Caring sciences out of the ivory tower. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2008; 22: 149–150.

- Morse J. M. Solberg S. M. Neander W. L. Bottorff J. L. Johnson J. L. Concepts of caring and caring as concept. Advances in Nursing Science. 1990; 13: 1–14.

- Narayanasamy A. The ACCESS model: A transcultural nursing practice framework. British Journal of Nursing. 2002; 8(12): 741–744.

- Nyman A. Sivonen K. The concept meaning of life in caring science. Nordic Journal of Nursing Research & Clinical Studies/Vård i Norden. 2005; 25(4): 20–24.

- Paley J. An archaeology of caring knowledge. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2001; 36(2): 188–198.

- Pergert P. Ekblad S. Enskar K. Bjork O. Bridging obstacles to transcultural caring relationship: Tools discovered through interviews with staff in pediatric oncology care. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2008; 12(1): 35–43.

- Polaschek N. R. Cultural safety: A new concept in nursing people of different ethnicities. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1998; 27: 452–457.

- Popps E. Ramsden I. Cultural safety in nursing: The New Zealand experience. International Journal of Quality in Health Care. 1996; 8(5): 491–497.

- Purnell L. The Purnell model for cultural competence. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2002; 13(3): 193–196.

- Ramsden I. Teaching cultural safety. New Zealand Nursing Journal. 1992; 83(5): 21–23.

- Searight H. R. Gafford J. Cultural diversity at the end of life: Issues and guidelines for family physicians. American Family Physician. 2005; 71(3): 515–522.

- Slettebo A. Nordic college of caring sciences in the years to come. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2009; 23(4): 623–624.

- Söderlund M. Three qualitative research approaches with relevance to caring sciences. Nordic Journal of Nursing Research & Clinical Studies/Vård i Norden. 2003; 23(2): 9–15.

- Todres L. Galvin K. Dahlberg K. Lifeworld-led health care: Revisiting a humanising philosophy that integrates emerging trends. Medicine. Health Care and Philosophy. 2006; 10(1): 53–63.

- Wärnå-Furu C. Health and appropriation in caring science research. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2010; 24(4): 635–637.

- Watson J. Smith M. Caring science and the science of unitary human beings: A trans-theoretical discourse for nursing knowledge development. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2002; 37(5): 452–461.

- Wear D. Insurgent multiculturalism: Rethinking how and why we teach culture in medical Education. Academic Medicine. 2003; 78(6): 549–554.

- Wikberg A. Eriksson K. Intercultural caring – an abductive model. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science. 2008; 22: 485–496.

- Williams R. Keywords2nd edition. Flamingo. London, 1983