Abstract

Background

: The development of implicit tests for measuring biases and behavioral predispositions is a recent development within psychology. While such tests are usually researched within a social-cognitive paradigm, behavioral researchers have also begun to view these tests as potential tests of conditioning histories, including in the sexual domain.

Objective

: The objective of this paper is to illustrate the utility of a behavioral approach to implicit testing and means by which implicit tests can be built to the standards of behavioral psychologists.

Design

: Research findings illustrating the short history of implicit testing within the experimental analysis of behavior are reviewed. Relevant parallel and overlapping research findings from the field of social cognition and on the Implicit Association Test are also outlined.

Results

: New preliminary data obtained with both normal and sex offender populations are described in order to illustrate how behavior-analytically conceived implicit tests may have potential as investigative tools for assessing histories of sexual arousal conditioning and derived stimulus associations.

Conclusion

: It is concluded that popular implicit tests are likely sensitive to conditioned and derived stimulus associations in the history of the test-taker rather than ‘unconscious cognitions’, per se.

Learning theorists have explored how the apparently limited theoretical and empirical implications of learning principles can be applied to the analysis of human sexual response conditioning. It has been established across numerous studies that human sexual arousal can be conditioned using both associative and reinforcement procedures. But human sexual learning and responding is complicated considerably by language and cognitive processes. These particular forms of influence have historically been far less amenable to study in the laboratory than stimulus-association and reinforcement contingencies. Nevertheless, the effects of language and cognition on sexual responding have been not only widely noted but indicated for decades by leading sex researchers as one obvious limitation to a learning approach (e.g. Bancroft, Citation1969; McConaghy, Citation1969).

Over the past 15 years, however, behavior-analytic researchers have been studying an exciting new process known as derived relational responding, which provides the basis for a behavior-analytic paradigm for the analysis of language and cognitive processes. Research on derived relational responding has been applied to the analysis of several dimensions of human sexual behavior, including sexual attitudes and stereotyping, histories of sexual offending, histories of sexual abuse, and patterns of sexual arousal in both normally developing and paraphilic populations. Most recently, this same derived relational responding paradigm has been used to develop behavior-analytic ‘implicit tests’ that can be used to ascertain histories of stimulus-stimulus or stimulus-response associations while circumventing the problem of ‘faking good’ encountered by many popular assessment methods, such as card sorting methods (e.g. Abel & Becker, Citation1985).

The current paper will outline the concept of derived relational responding and illustrate how it has enormously expanded the capacity of a non-mentalistic learning approach to explain the processes underlying complex human sexual behavior, as well as aid in the development of clinical and forensic tools for assessing histories of sexual responding or sexual stmulus associations, in a non-invasive and implicit manner.

A review of the literature on human sexual arousal conditioning with human populations reveals an interesting and worrying pattern. The lion's share of studies both conducted and cited appear to predate the 1990s (although a small number of well-cited conditioning studies have been conducted since, e.g. Both et al., Citation2008; Hoffmann, Janssen, & Turner, Citation2004; Lalumière & Quinsey, Citation1998; Letourneau & O'Donohue, Citation1997; Plaud & Martini, Citation1999). This is the case for both basic laboratory studies into respondent (e.g. Langevin & Martin, Citation1975; Lovibond, Citation1963; McConaghy, Citation1969, Citation1970; Rachman, Citation1966; Rachman & Hodgson, Citation1968) and operant (i.e. instrumental) processes (e.g. Cliffe & Parry, Citation1980; Quinn, Harbison, & McAllister, Citation1970; Rosen, Shapiro, & Schwartz, Citation1975; Schaefer & Colgan, Citation1977), as well as applied studies employing the concepts of learning theory in treatment settings (e.g. Earls & Castonguay, Citation1989; Feldman & MacCulloch, Citation1971; Rosen & Kopel, Citation1977; see also Roche & Quayle, Citation2007, for a review). Even some pioneers of the learning approach to human sexuality have long questioned the explanatory scope of respondent and operant processes. Indeed, 40 years ago, influential researchers such as John Bancroft (Citation1969) suggested that respondent and operant processes were insufficient in explaining complex and real-world human sexual behavior (see also McConaghy, Citation1969). The learning account available to researchers throughout this period failed to provide an adaquate explanatory framework for the emergence of sexual behavior in novel contexts or those instances of sexual behavior without an apparent explicit history of reinforcement or stimulus association (e.g. fetishism; see Roche & Barnes, Citation1998).

The missing link: derived relational responding

In addition to being able to discriminate (i.e. detect and respond to) specific stimuli, organisms are also capable of responding to relations between stimuli, such as similarity, difference, distance, greater than, and so on. This is known as relational responding. Non-verbal organisms are capable of learning to respond to such formal relations, such as size and distance, via traditional learning processes such as operant conditioning (see Reese, Citation1968). Verbal organisms, however, display a unique ability to respond to arbitrary stimulus relations such as oppositeness, value, and time and to derive relations between stimuli not directly associated with each other. This form of relational responding is known as derived relational responding. Originally researched as stimulus equivalence in the context of children's language learning (Sidman, Citation1971), in the past 15 years, the significance of this phenomenon for wide-reaching behavioral account of human language and cognition has become increasingly apparent.

Derived Relational Responding is best demonstrated with a description of a typical stimulus equivalence procedure. An individual is presented with a series of stimulus-matching tasks on a computer. One of two arbitrary sample stimuli (we will refer to them here as A1 and A2) is presented in the centre of the screen, and two comparison stimuli, B1 and B2, are presented at the bottom of the screen. The participant is taught to make a discrimination between B1 and B2 conditional upon the sample. That is, given A1 as a sample, choosing B1 is reinforced, whereas given A2, choosing B2 is reinforced. The same procedure is then used to teach subjects to choose comparison stimulus C1 when given A1 and C2 when given A2. What Sidman (Citation1971) and subsequent researchers established was that given this training alone, verbally able humans will spontaneously match B1 to A1, B2 to A2, C1 to A1, and C2 to A2 (i.e. demonstrate symmetry between the stimuli) in the absence of feedback, reinforcement, or even instructions to do so. Furthermore, they will match B1 to C1, C1 to B1, B2 to C2, and C2 to B2 (i.e. demonstrate transitivity between the stimuli). When this occurs, the stimuli are said to form a derived stimulus equivalence relation (see Sidman, Citation1986; see also Barnes, Citation1994; Fields, Adams, Verhave, & Newman, Citation1990).

A Relational Frame Theory (RFT; Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, & Roche, Citation2001) account of language and cognition draws upon and elaborates the stimulus equivalence phenomenon described above. The different forms of relational responding (difference, opposition, greater than, less than, etc.) can also be derived without explicit training (Dymond and Barnes, Citation1995, 1990; Lipkens, Hayes, & Hayes, Citation1993; Roche & Barnes, Citation1996). Derivations of relations other than equivalence require specific nomenclature to allow researchers to speak with precision about the relations under analysis. Mutual entailment means that if A is related to B, then B is related to A in a complimentary fashion. For example, if A is opposite to B, then B is opposite to A. If A is more than B, then B is less than A. Combinatorial entailment occurs when three or more stimuli are related. If A is opposite to B, and B is opposite to C, then the relation that is derived between A and C is one of equivalence, because both are opposite to B. Combinatorial entailment refers to the reciprocal relationships that exist between two stimuli as mediated by other intermediary stimuli (Blackledge, Citation2003).

The feature of the RFT account which is most important for our discussion of sexuality is the finding that the psychological functions of any stimulus will be transformed by its relation to other stimuli in a derived relational network (Transformation of function). This was first demonstrated in the context of sexual arousal responses by Roche and Barnes (Citation1997), experiment 1). In that experiment, seven subjects were trained in a series of conditional discrimination tasks using nonsense syllables as stimuli. This training led to the emergence of three derived equivalence classes; A1-B1-C1, A2-B2-C2, and A3-B3-C3. After this training was complete, sexual and non-sexual functions were established for C1 and C3 (respectively) through a respondent conditioning procedure. The acquisition of these functions was monitored and assessed in terms of phasic skin resistance responses. Though only C1 and C3 were trained with sexual and nonsexual functions, respectively, these functions were pontaneously transformed in accordance with the derived equivalence relation; subjects showed a heightened arousal response to A1 over A3 (even though the A stimuli had never been directly paired with sexual stimuli or C stimuli). These findings demonstrate that humans are capable of responding sexually to any given stimulus in terms of a sexual one to which it is indirectly and arbitrarily related.

The Roche, Barnes-Holmes, Smeets, Barnes-Holmes, and McGeady (Citation2000) demonstrated a far more complex example of the derived transformation of sexual arousal responses. In that study, derived sexual arousal responses were transformed in accordance with opposite relations, rather than equivalence relations, and brought under further contextual control. Subjects were trained to form a derived equivalence relation (or coordination relation) containing three arbitrary nonsense syllables labelled A1, B1, and C1. They were also taught that two further nonsense syllables (B2 and C2) were the opposite of A1. Sexual and non-sexual elicitation functions were then established for B2 and B1, respectively. B2 and C2 participated in an unreinforced derived relation of coordination with one another, as they were both opposite to A1 (remember that this derived relation of coordination was not reinforced or formed through stimulus associations; it was derived). Subjects produced a sexual arousal response to C2 due to this derived relation with B2 but did not respond to C1 with a physiological arousal response. Furthermore, the experimenters brought the performance under contextual control. That is, when C2 was presented in the presence of a previously established cue for opposite, subjects produced no sexual responses to C2. In contrast, when C1 was presented in the presence of the opposite cue, a sexual response was observed.

Roche et al. (Citation2000) data demonstrate the remarkable flexibility of human sexual responses and their susceptibility to highly complex forms of stimulus control (see also Roche & Dymond, Citation2008). The derived transformation of sexual responses can offer a new paradigm for understanding complex human sexual behavior that compliments the traditional learning approach based strictly on a direct contingency analysis. That is, derived relational responding and the transformation of stimulus functions represent examples of behavior controlled by remote, rather than local contingencies.

The remote contingencies that can lead to the emergence of derived sexual responses can be represented by verbal practices. For instance, rules, norms, mores, and taboos all constitute forms of verbal contingency that specify relations between stimuli (e.g. ‘sex’ and ‘dirty’) in often complex and subtle (i.e. indirect) ways. A subject's past participation in a verbal environment (i.e. a culture) provides many hundreds of training exemplars that establish complex derived relational networks through which functions of stimuli may be transformed, and this can explain the emergence of apparently untrained sexual responses. As an example, a culture that simultaneously teaches that sexual promiscuity is bad and, at other times, that bad behavior is sometimes exciting (e.g. speeding in one's car) is paradoxically making likely the derived transformation of the psychological functions (i.e. experience) of promiscuity into an exciting desirable activity, at least for some individuals. This occurs because of the way in which the various terms were framed relationally in language, whether explicitly, or in turn by further derived relations (e.g. innuendo, jokes). In this sense, language can lead to the emergence of sexual responses and practices in a very real way.

The RFT approach to language has led to the emergence of a definition of attitudes in terms of a network of trained and derived stimulus relations, established by and within a community (Grey & Barnes, Citation1996; see also Moxon, Keenan, & Hine, Citation1993; Roche, Barnes-Holmes, Barnes-Holmes, Stewart, & O'Hora, Citation2002; Schauss, Chase, & Hawkins, Citation1997). Once conceived this way, sexual attitudes are measureable as forms of relational responding. This insight opens up a whole new avenue of research for the experimental analysis of complex human sexual behavior. For instance, in one study (Grey & Barnes, Citation1996), participants were provided with the necessary conditional discrimination training to form the following three derived equivalence relations: A1-B1-C1, A2-B2-C2, and A3-B3-C3, using nonsense syllables as stimuli. Participants then viewed the video contents of VHS video cassettes that were clearly labelled with the A1 and A2 stimuli. One of the cassettes contained sexual/romantic scenes, while the other contained religiously themed scenes. Subsequently, subjects were asked to categorize four novel video cassettes, each labelled as B1, C1, B2, or C2. They were given no information about these cassettes, but they categorized them according to the derived equivalence classes. That is, subjects classified the B1 and C1 cassettes in the same way as the A1 cassette and the B2 and C2 cassette in the same way as the A2 cassette. In effect, the study demonstrated the sexual and religious evaluative functions of the A-labeled cassettes and the derived relations in which the A stimuli participated, transformed the functions of the C-labeled cassettes, such that these were responded to as sexual or religious as appropriate.

Watt, Keenan, Barnes, and Cairnes (Citation1991) also used a stimulus equivalence paradigm to assess subjects’ social history of exposure to sectarianism in Northern Ireland. In that environment, surnames are often indicative of religious background. In the study by Watt et al. (Citation1991), subjects from both Northern Ireland and England were trained to form ‘linear’ equivalence relations (A goes with B, B goes with C) containing Catholic names as A stimuli, nonsense syllables as B stimuli, and Protestant symbols as C stimuli. The predicted derived relations were of the form ‘Catholic name’–‘Protestant symbol’. During the testing phase, subjects were presented with the Protestant symbols as sample stimuli and two Catholic names and a novel Protestant name as comparison stimuli. English subjects produced the derived equivalence relations as expected. However, Northern Irish subjects typically failed to do so. These subjects choose the Protestant name comparison when presented with the Protestant symbols as samples. In effect, the extended social history of these subjects interfered with the derivation of the equivalence relation and was, therefore, detected by the stimulus equivalence procedure.

The procedure offered by Watt et al. represented a first possible implicit test method within behavior analysis that predated the advent of the popular Implicit Association Test (IAT; Greenwald, McGhee, & Schwartz, Citation1998) by several years. Subsequent research utilized the paradigm by Watt et al. (Citation1991) to study various different social histories established outside the laboratory, such as: social discrimination of Middle Eastern People (Dixon, Rehfeldt, Zlomke, & Robinson, Citation2006,) gender identity (Moxon et al., Citation1993, Kohlenberg, Hayes, & Hayes, Citation1991; Roche & Barnes, Citation1996), self-esteem (Barnes, Lawlor, Smeets, & Roche, Citation1995, Merwin & Wilson, 2008), and child sexual abuse (McGlinchey, Keenan, & Dillenburger, Citation2000; Roche, Ruiz, O'Riordan, & Hand, Citation2005). However, the Watt et al. procedure was never harnessed into a widely used implicit test format (see below).

The social cognitive approach

The stimulus equivalence test method for assessing social and personal histories has interesting parallels with ongoing research in the social cognitive literature. Specifically, the growing area of implicit testing seeks to develop procedures, which can measure attitudes that are beneath awareness or that may be withheld for fear of social sanctions. Of these, the most popular by far is the IAT (Greenwald et al., Citation1998). The IAT records the speed with which participants sort particular stimuli into categories. The core assumption underlying the test is that it is easier to assign a common response to two stimuli if they are associated in memory. In an IAT, a subject responds to a series of items that can be classified into one of four categories. Typically, two of these categories represent a concept, such as race, and two represent an attribute, such as good and bad. In one task, subjects are instructed to produce the same response (a right hand key press) for any displayed items representing one concept and one attribute (e.g. African-American and Bad) and with a left-hand key press to any items from the remaining two categories (e.g. European and Good). In a second block of testing, the instructions are juxtaposed so that each category shares a common response with the other attribute (e.g. African-American and Good). In the first task block (labeled the ‘consistent’ block), the required responses are consistent with the assumed pre-experimental associations of the participants. The second task block (the ‘inconsistent’ block) is inconsistent with the individual's social history. Thus, slower and less accurate responding is typically recorded on the inconsistent compared to the consistent block. The differential in response time across the blocks is the IAT effect, and it is used as an index of unconscious bias (e.g. racial bias).

One significant problem with the IAT is that explanations for the effect offered by its creators are either non-committal or resting on untested or untestable assumptions. More specifically, there is some uncertainty regarding precisely what the IAT is measuring (e.g. Rothermund & Wentura, Citation2004) and how the effect should be best measured (Blanton & Jaccard, Citation2006; Blanton, Jaccard, Gonzales, & Christie, Citation2006; see also De Houwer, Citation2001; De Jong, van der Hout, Rietbroek, & Huiijding, Citation2003; Fazio & Olson, Citation2003; Karpinski & Hilton, Citation2001; Mierke & Klauer, Citation2003; Olson & Fazio, Citation2003; Sherman, Rose, Koch, Presson, & Chassin, Citation2003). Others have even called the IAT's validity into question (e.g. De Houwer, Citation2006) and have challenged claims that we can draw inferences about the traits or states of individuals on tacit psychological dimensions. In particular, Jan De Houwer (Citation2001, Citation2006) has been particularly vociferous in calling for a clearer operational definition of the IAT test effect. Most recently, De Houwer (Citation2011) has outlined the problems inherent in using behavioral manifestations (e.g. response times on IAT tasks) of assumed cognitive structures (e.g. unconscious bias) to infer the existence of those very constructs. In the same paper, he outlines the potential benefits for both cognitively oriented and functionally oriented (e.g. behavior-analytic) research in combining both approaches into a functional cognitive framework. It is argued that the functional approach is useful to the social-cognitivist, for example, in that it provides useful information about the environmental causes of behavior and the environmental variables which can be experimentally manipulated to produce or alter a behavioral effect, without necessary reference to mental constructs as causal events. This information, in turn, allows the cognitively oriented psychologist to make more informed inferences about the mental constructs assumed to mediate such behavioral effects by eliminating a priori assumptions and providing clear information about the input to mental processes. The functional and cognitive approaches can be integrated but remain conceptually distinct. However, the functional approach informs the cognitive approach as to the facts, which need to be accounted for with mental explanations, without reference to the mental explanations themselves, while the cogntive explanations provide a stable theoretical framework for the development of functional knowledge.

In our work, we adopt a functional approach to implicit testing but we appreciate the need to remain mindful of the heuristic value of mentalistic organising concepts. Mental explanations can sometimes benefit the functional analyst by organizing existing knowledge and making useful predictions, which can prove fertile to future research even if that research then takes place using entirely non-mentalistic concepts. For example, the concept of attitude is intrinsically mentalistic and, yet, can serve as a useful metaphor in organising specific varieties of verbal behavior (evaluative verbal responses) for specific research purposes (e.g. predicting future non-verbal behavior such as racially motivated violence).

In our functional approach, we view the IAT as a measure of an individual's verbal history and practices, which may or may not in turn reflect personal attitudes or affective states and dispositions. IAT effects are conceived in terms of subjects’ fluency with the relevant verbal categories and their degree of experience at juxtaposing members of those verbal categories. For instance, an individual who has many dealings with people of a specific race and has encountered both pleasant and unpleasant individuals from this racial group will likely find it easy to juxtapose racial and evaluative terms in an IAT according to the test rules across the two test blocks. Such an individual will show no IAT effect (i.e. response time or accuracy differential across the text blocks). On the other hand, if they have experienced mostly unpleasant individuals from one racial group or other, the juxtaposition of response rules across the IAT blocks will likely expose a fluency differential across those two blocks (i.e. an IAT effect). We refer to this as the behavioral model of the IAT (see Roche et al., Citation2005).

The behavioral model of the IAT was tested empirically by Gavin, Roche, and Ruiz (Citation2008) using nonsense syllables as stimuli and experimentally produced derived relations between them as laboratory analogs of verbal relations between words in the vernacular. Two equivalence relations were established in the usual manner, leading to the two classes of nonsense syllables, labeled here as A1-B1-C1 and A2-B2-C2, where the A-C relations were derived, not reinforced. An IAT-type test was then adminstered to measure subejcts’ ability to respond in the same way to common class member pairs (e.g. A1 and C1) compared to cross-class pairs (e.g. A1 and C2). Not surprisingly, more errors were made in responding under rule conditions in which a common response was required for incompatible, compared to compatible sitmuli. Thus, IAT effects were generated using only directly manipulable variables, without recourse to mentalistic language or appealing to hypothetical processes. These entirely laboratory produced IAT effects were subsequently shown to be manipulatable vis-à-vis reversals of some of the baseline relations underlying the derived equivalence relations (Ridgeway, Roche, Gavin, & Ruiz, Citation2010). Such findings strengthen any claims that the IAT test format is sensitive to past stimulus associations, perhaps even including those that a subject would wish to conceal. However, they pose a challenge to any view that IAT effects are necessarilly a reflection of internal beliefs, intentions, or predispositions. This may be the case, but these are not necessary conditions for IAT effects to emerge, and thus the scientifically conservative position to adopt on the matter is a functional one. What we can say with certainty is that IAT measures past stimulus associations in the history of the test taker and that these sitmulus associations may be directly established or derived.

Interestingly, in-keeping with this functional perspective, some social cognitivists have suggested an environmental-style account of the IAT. Specifically, it was first suggested by Karpinski and Hilton (Citation2001) that IAT effects may reflect only the word and concept associations to which a person has been exposed to in their past. They may not reflect the extent to which the person endorses those evaluative associations. Other researchers have suggested that subjects’ experiences of the words employed in an IAT test can alter the IAT effect itself (see McFarland & Crouch, Citation2002; Ottaway, Hayden, & Oakes, Citation2001; but see also Dasgupta, Greenwald, & Banaji, Citation2003; Gawronski, Citation2002).

Implicit testing has been of particular interest in the field of forensic psychology, especially with regard to sexual offending. When dealing with sexual offenders, there is a great deal of concern amongst researchers about what are referred to as ‘faking good’ responses. For example, a paedophile offender population may wish to hide their unchanged sexual attitude toward children following a therapeutic intervention for fear of legal sanctions. Alternatively, they may wish to fake more acceptable attitudes as part of an assessment procedure that may increase chances of parole or other privileges. Therefore, the advent of implicit testing procedures has been welcomed in the field with an increasing number of studies attempting to measure the ‘implicit cognition’ of offenders or of at risk segments of the population (Brown, Gray, & Snowdon, Citation2009; Dawson, Barnes-Holmes, Gresswell, Hart, & Gore, Citation2009; Gannon, Wright, Beech, & Williams, Citation2006; Gray, Brown, MacCulloch, Smith, & Snowden, Citation2005; Keown, Gannon, & Ward, Citation2008a, Citation2008b; Kamphuis, De Ruiter, Jannssen, & Spiering, Citation2005; Malamuth & Brown, Citation1994; Mihailides, Devilly, & Ward, Citation2004; Nunes, Firestone, & Baldwin, Citation2007).

Gray et al. (Citation2005), Mihailides et al. (Citation2004), and Nunes et al. (Citation2007), all have reported IAT effects across child-sex offender and non-offending populations that allowed the two groups to be distinguished at the group level. In the study by Gray et al., effects bordered on allowing for discrimination at the level of the individual. In another study, Snowden, Wichter, and Gray (Citation2008) used an IAT to successfully discriminate homosexual from heterosexual men. Finally, researchers have also employed modified Stroop procedures to identify sexual interests of sex offenders (see Ó'Ciardha & Gormley, Citationin press).

Just as some social cognitivists have been questioning the mentalistic assumptions of the IAT, theorists in the forensic psychology field have been voicing concerns with regard to the purely internalist nature of many theories of sexual offending. For instance, Gannon (Citation2009) argued that seeking an explanation of sexual offenders’ actions merely by appeal to the internal characteristics of the offender risks ignoring factors outside the mind. Similarly, Ward & Casey (Citation2010) argued that a theoretical link between ‘what goes on inside an offenders head and external social and cultural factors’ is necessary to avoid neglecting vital causal factors in offending behavior. These concerns suggest a need for functional accounts of the development of sexual offending behaviour, which take into consideration obvious environmental factors, such as those located in the subjects’ history as part of a verbal community (i.e. a culture). Functional approaches, such as the derived relations account of sexual behavior and implicit testing outlined here, address these concerns directly by pointing to observable and manipulable environmental contingencies that may produce or alter sexual behavior, without reference to mental constructs as causal events. Indeed, there is a small literature on the development and use of behavior-analytic implict tests in the field of forensic psychology and sex research, and it is to this topic that we will now turn ourt attention.

Behavior-analytic implicit tests

As outlined above, there are several concerns abroad with the IAT at both a conceptual and a procedural level. These do not detract from the exciting research opportunities opened up by this tool. Nevertheless, a functional approach requires the researcher to markedly modify the IAT and the conceptualization of test results. In our ongoing research, we have systematically eliminated and modified features of the IAT delivery format and data analysis methods. A review of the many modifications we have made is not relevant here but the reader is referred to Gavin et al. (Citation2012) and Ridgeway et al. (Citation2010) for a review. The important point here is that the behavior-analytically modified IAT appears to offer the same types of test outcomes with the benefit of employing an entirely transparent and well-understood delivery format. This method has also been employed with a sex offender population in pilot research, first described by Roche et al. (Citation2005). A small data set gathered from this population was first described by Roche et al. (Citation2005), but a further expanded data set including both additional offenders and offender-types is presented here for the first time.

The original context of the research by Roche et al. (Citation2005) on sex offender populations was to attempt to identify whether or not those convicted of child pornography offences display the same types of child-sex associations (i.e. a paedophilic orientation) as those convicted of contact sex offences. Qualitative findings suggest that some users of child pornography are not exclusively pedophilic in orientation but may have used child pornography only as part of some other overarching sexual interests (see Quayle & Taylor, Citation2002, Citation2003). Moreover, the link between the consumption of child pornography and contact sex offending is far from clear (see Endrass et al., Citation2009), and there may even be a inverse relation between the two (i.e. the use of child pornography may actually reduce the likelihood of contact offences; see Diamond, Jozifkova, & Weiss, Citation2010). Understanding these complex issues in greater detail may have significant implications for the treatment and incarceration of contact and internet sex offenders.

Our behavior-analytically modified child-sex IAT test was designed to assess fluency in associating terms related to sexuality with images of children compared to images of adults. On one block of tasks, subjects are instructed to press a left hand key for sexual terms and images of children and a right hand key for ‘horrible’ words and images of adults. On every trial, a cartoon image of a child or adult, or a sexually explicit or disgusting word is presented. Each of the four trial types are presented 20 times in a quasi-random order in a block of 80 trials. For sex offenders against children, these tasks are presumably class-consistent. That is, children are already likely to be categorized as sexual rather than horrible. Thus, for this group, these tasks are defined as consistent tasks.

As in a standard IAT, the test rules are changed for a further block of trials. Specifically, subjects are presented with rules instructing them to press left for sexual terms and images of adults and to press right for horrible words and images of children. For the sex offenders against children, these tasks presumably pose a categorization conflict, insofar as they require the subject to produce distinct instrumental responses (i.e. left and right presses) to stimuli that normally go together (i.e. sex and children). Thus, these tasks are referred to as inconsistent tasks. In both blocks, cartoon images were hand drawn specifically for this research. Adult faces were typically in the 40–50 years age range. Child faces were broadly prepubertal-pubertal. Sexual words were boldly sexual (e.g. masturbate and horny), and disgusting words were clearly aversive and assumed to be non-sexual for the majority of the population (e.g. vomit and ulcer). Ten exemplars from each category are presented at random from trial-to-trial.

Data gathered from 60 subjects across six groups (10 per condition) are considered here: female control volunteers, male control volunteers, contact sex offenders against children, internet offenders (convicted of child pornography possession), male sex offenders against adults, and male prisoners without a sex offence record. Control subjects and offender populations were matched for age but not for intellectual ability or numeracy. Prisoners were for the most part currently serving sentences but a small number from each group were currently on probation and were contacted through probation services. Specific histories of treatment are not known but all offenders typically undergo some form of rehabilitation within the Irish penal system, so current or past treatment was assumed to be universal. Specific offence details for subjects were not sought, but broad category assignment to one of the offender categories used here was made for the researchers by prison officials.

A prior categorization test for all stimuli was administered before the two key IAT blocks to ensure familiarity with the various stimuli and their correct category assignment. Thus, our test constituted a three-block modified IAT.

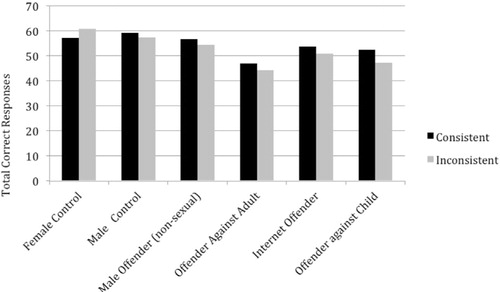

shows the total number of correct responses on each of the two main test blocks. In this version of the IAT, response accuracy rather than reaction time is used as the primary metric, because a finite response window of 3 sec was enforced (see Gavin et al., 2012, for rationale). The difference score displayed in was calculated by subtracting the total correct responses on the consistent block from that for the inconsistent block. For this preliminary analysis, data are not normalized or subjected to the IAT scoring algorithm (designed for reaction time data). A positive difference score is indicative of a positive child-sex association. It can be seen that, as expected, the largest positive score was produced by the contact child sex offender group and the second largest by the internet offender group. illustrates these relative response accuracy differentials graphically.

Fig. 1. Total correct responses during consistent and inconsistent IAT test blocks for all groups of subjects. The difference in response accuracy across the two blocks is indicative of the size of the IAT effect. Note that the differential is in the same direction (consistent greater than inconsistent) for all male subject groups but not for the female subject group.

Table 1. Total number of correct responses on both blocks of a modifed IAT for a sample of offenders and control subjects. C refers to consistent test blocks and I refers to inconsistent test blocks. A positive difference score is indicative of a pre-exisitng child-sex association.

All male groups (including controls) showed a slightly positive effect for child-sex associations relative to adult-sexual (i.e. the former were stronger than the latter). However, female control subjects showed a resistance to forming child-sex relations (an effect also observed in a larger study by Gavin et al., 2012). That is, female controls showed higher response accuracy on inconsistent (adult-sexual) tasks (M = 57.1 SD = 16.4) compared to consistent (child-sexual) tasks (M = 60.8 SD = 12.5). T-tests were applied to data from all six groups to assess the significance of the consistent-inconsistent block response accuracy differential (i.e. IAT effect). For all t-tests conducted, alpha was set at p≤0.008 in accordance with Holm's (Citation1979) sequential Bonferroni adjustment for conducting multiple t-tests. For all analyses, eta squared statistics are provided and the guidelines of Cohen (Citation1988) are employed to indicate effect size. The only significant positive IAT effect was observed was for the contact sex offenders against children (t=3.452, df=9, p < 0.008, eta squared = 1.134, large effect size). In simple terms, this group of subjects produced significantly more correct responses when test block instructions were consistent with a history of child-sex associations than when they were inconsistent.

At least for this small sample, the Internet offenders did not display a significant child-sex association. Of course, this group did display the second largest child-sex association effect, and such an effect may likely become statistically significant if the sample were to be expanded slightly or if various data cleaning techniques were employed, as they typically are on the IAT (we prefer to observe raw data effects as is tradition in the single subject methodology of the experimental analysis of behavior). Interestingly, the sex offenders against the adult group showed the next largest positive IAT effect, possibly indicative of the widely observed comorbidity across the paraphilias (e.g. Kafka & Hennen, Citation2002) and the lack of a clear boundary across pedophilic and other sexual interests (Taylor & Quayle, Citation2003).

It is important to remember that we do not yet know the role that child-sex stimulus associations play in the development of a pedophilic orientation (i.e. causal or outcome, a defining or a secondary characteristic). In one study, Seto, Cantor, and Blanchard (Citation2006) found that child pornography offence conviction was in fact a better indicator of pedophilia than contact offending, when the measure of pedophilic interest was assessed using plethysmograpically recorded responses to images of children and adults. On the other hand, research also suggests that child pornography users consist of quite a diverse group that do not clearly display the key characteristics of the contact pedophile (see Quayle, Erooga, Wright, Taylor, & Harbinson, Citation2006; Quayle & Taylor, Citation2002, Citation2003; see also Ó Ciardha & Gannon, Citation2011, for a review of this complex issue). One way in which we can begin to get a handle on the role of child-sex associations and the unique psychological characteristics of any demographic group is to study more extensively the frequency of child-sex stimulus associations found in the histories of the general population. One recent study (Gavin et al., 2012) attempted to do just this using a behavior-analytically modified IAT.

The study by Gavin et al. (2012) recruited 54 adults from the general population (half were male, half were female). Subjects were exposed to a modified IAT similar to that described above. However, in this case, all stimuli were words. At a group level (males and females combined), higher response accuracies were observed when child and non-sexual terms shared a response and when adult and sexual terms shared a response. This effect was statistically significant. When subjects were split by gender, however, only the female participants’ test effect was statistically significant. That is, females displayed a culturally appropriate implicit test effect (child-sex associations were weaker than adult-sex associations), whereas male participants did not (non-significant difference between the two association types but a trend in the direction of stronger child-sex than adult-sex associations). That is, for females, children were categorized as definitively non-sexual, whereas for males, there was at least ambiguity in this regard. This finding suggests that males and females share different histories with regard to how children are categorized sexually. In effect, the modified IAT allowed the researchers to take a ‘snapshot’ of the organization of the verbal contingencies controlling male and female responses to children. It was also non-invasive, quick to administer, and likely reduced social desirability effects in a research context in which we would expect to encounter considerable problems in this regard. Most importantly, in the current context, it demonstrated that, while a random sample of males may not display significant histories of child-sex associations, their history appears to be not incompatible with this association. This should be taken into account in any explanation of sex offending in terms of characteristic stimulus-associations or in any account that assumes a low prevalence rate of child-sex associations across the population.

In recent years, two explicitly behavior-analytic alternatives to the IAT have been developed. Both employ many of the same core behavioral processes but are presented in quite different ways. The first is the Implicit Relational Assessment Procedure (IRAP; Barnes-Holmes, Hayden, Barnes-Holmes, & Stewart, Citation2008). The IRAP is in many ways procedurally similar to the IAT. However, each trial of the IRAP displays two stimuli (rather than just one) on screen (e.g. ‘Child’ and ‘Sexual’) along with a contextual cue which specifies the relation between the two stimuli (e.g. ‘Same’ or ‘Opposite’). The subject is required to respond quickly to this resulting relational statement (‘Child SAME Sexual’ or ‘Child OPPOSITE Sexual’) with a key press that corresponds to one of two response options (e.g. for ‘TRUE’ press z, for ‘FALSE’ press m). After the subject responds, the computer displays feedback indicating if they were ‘Correct’ or ‘Wrong’. Like the IAT, trials in the IRAP are organized into blocks. In one type of block, the responses that produce the ‘correct’ feedback are those that are consistent with social norms (e.g. Child OPPOSITE Sexual − TRUE = Correct) while the other block requires responses that are inconsistent with social norms. A child-sex IRAP would function as follows. In the consistent blocks, subjects would be required to respond to the statement Child SAME Sexual as FALSE and Child OPPOSITE Sexual as TRUE. In the inconsistent blocks, the subject would be required to respond to the statement Child SAME Sexual as TRUE and to Child OPPOSITE Sexual as FALSE. The core assumption of the IRAP is that subjects will respond more quickly to relations that are consistent with their verbal and non-verbal history with the stimuli.

The behavioral framework within which IRAP results are interpreted is the Relational Elaboration Coherence model (REC; Barnes-Holmes, Barnes-Holmes, Stewart, & Boles, Citation2010), a model which has emerged from RFT (outlined earlier). According to the REC model, each individual trial on the IRAP produces an immediate and brief response to the relation presented before the participant presses a response key. The probability of this initial response is a function of subjects’ verbal and non-verbal history with the stimuli and the current contextual cues (i.e. the relational stimulus, such as the word Opposite on screen). The most probable response will likely be emitted first, and as such, if this immediate response coheres with the response required by the current IRAP trial rule, then the response latency will be lower. If the required response is in opposition with the subjects’ immediate relational response, then the correct (as defined by the contingencies of the specific trial) response will be emitted more slowly. Across multiple trials, the average latency on inconsistent trials will be higher than the average latency for consistent trials.

The foregoing provides a basic explanation for the IRAP effect, but the REC model extends the explanation to account for why implicit measures and explicit questionnaire methods so often diverge in their results. More specifically, when completing questionnaires or other so called ‘explicit’ measures of attitudes, the subject is under little time pressure and can therefore engage in complex and extended relational responding (i.e. thinking), which allows them to produce a response that is coherent with other responses in their behavioral repertoire (see Barnes-Holmes, Hayes, & Dymond, Citation2001) such as: ‘it is wrong to categorize children as sexual’. It is also possible under these circumstances to produce a response, which coheres with the social expectations of others. However, when exposed to the IRAP procedure, subjects are under significant pressure to respond quickly (commonly within 2000 ms) and, therefore, have little time to engage in the elaborate relational responding processes necessary to produce alternative socially desirable responses. In effect, the most likely responses under time constraint conditions are those that are immediate and brief and, therefore, direct measures of history, unmediated by local relational activity.

One IRAP study set out to determine if the IRAP could be used to differentiate between child sexual offenders and a normal population group (Dawson et al., Citation2009). Sixteen subjects who had been convicted of a contact sexual offence against a child (the offender group) and 16 male non-offenders recruited from a college population (the control group) completed an IRAP procedure and a Cognitive Distortion Scale (CDS; Gannon et al., Citation2006). The IRAP stimuli consisted of two category labels (‘Child’ and ‘Adult’) and two sets of target stimuli (‘sexual’ words and ‘non-sexual’ words). During the consistent blocks, subjects were required to respond with ‘true’ to the relations ‘Adult–Sexual’ and ‘Child–Non-sexual’, while in the inconsistent blocks, subjects were required to respond in the opposite way.

The IRAP successfully detected a difference between the control group and the offender group. Furthermore, the IRAP was able to identify the specific relation on which the two groups differed. On Child-Sexual trials, the offender group did not show a significant IRAP effect, responding equally quickly to Child-Sexual-False and Child-Sexual-True. According to the REC model, this effect would be due to the offender group immediately responding to child-sexual relations as both true and false. This makes sense in the context of the Implicit Theories of Sexual Offending Model (Gannon et al., Citation2006), which states that child sexual offenders conceive of children as simultaneously being sexually receptive, while also being innocent and non-threatening when compared to potential adult sexual partners. In the study by Dawson et al. (Citation2009), the CDS did not differentiate between the two groups. Again, this may not be surprising. In this case, all members of the offender group had participated in a Sexual Offender Treatment Program, which targeted the cognitive distortion associated with offending. When under low time pressure during completion of the CDS, the offenders would have been able to respond consciously in a manner which was consistent with their treatment, thus not showing any difference from controls.

Another more recent development within the experimental analysis of behavior and the second explicitly behavior-analytic alternative to the IAT is the Function Acquisition Speed Test (FAST; O'Reilly, Roche, Ruiz, Ryan, & Campion, (Citationaccepted), O'Reilly, Roche, Ruiz, Tyndall, & Gavin, Citationin press). This test emerged directly from the stimulus equivalence method developed by Watt et al. and several published studies that have functionally analyzed the necessary and sufficient conditions to produce IAT effects (briefly outlined earlier). The FAST combines what we have learned from both these sources and delivers a procedurally implicit and rapidly administered test format. Procedural implicitness refers to the degree to which the stimulus-stimulus relations (i.e. associations) under analysis and the purpose of the test are discriminable by a subject. This is to be distinguished from outcome implicitness, which refers to the implicitness of the stimulus associations being measured (i.e. whether the subject has ever become aware of the associations in the past; see De Houwer, Citation2006). In order to illustrate how the FAST achieves this, let us return briefly to the Watt et al., IRAP, and IAT procedures.

In the IRAP and Watt et al. procedures, two stimuli are presented together on screen and the subject must relationally assess this pair (i.e. by matching them or confirming or disconfirming the relation between them, respectively). In the IAT, only one stimulus is presented on screen on each trial, but two pairs of stimuli are presented as category labels (e.g. European and Bad). In the first two test types, while a subject has no way of being certain what the purpose of the measure is, the fact remains that the stimuli whose relation is under analysis are presented simultaneously during the testing phase. Similarly, in the IRAP and IAT, the relation under analysis is specified in the rules of the block (e.g. ‘Press SAME for Child Images and Sexual Words’). These rules explicitly draw attention to stimulus pairs whose relation is under analysis (e.g. child images and sexual words). Thus, procedural implicitness is compromised by procedures such as the IAT, the IRAP, and the Watt et al. method.

The FAST makes a small modification to the Watt et al., IAT, and IRAP methodologies, which allows us to retain the basic core process while at the same time improving procedural implicitness, by more effectively disguising the purpose of the test. Specifically, the FAST requires the subject to learn trial-by-trial to produce common responses for two stimulus pairs (i.e. from two functional response classes), where all stimuli are presented individually in the absence of prior or simultaneous instructions regarding response strategy. That is, subjects are presented with stimuli individually on separate trials and are taught via reinforcement (i.e. verbal feedback presented by the computer) to respond with the same key press (i.e. a left or right key press) for two of the stimuli and with another response for a further two stimuli. The rate at which a subject learns to produce the common response for any two stimuli, presented separately, can be compared to the learning rate for producing distinct responses for these two stimuli, again across separate trials. Such a procedure requires no conditional discrimination training for equivalence class formation (as in the Watt et al. procedure), is not demanding on the subject (i.e. there are no relations to derive), and is fast to administer (unlike the IRAP). In addition, it requires no instructions (unlike the IAT and IRAP), because subjects learn to respond via reinforcement alone. The less demanding nature of the FAST format compared to the Watt et al. or IRAP procedure also make it more appropriate for use with populations demonstrating below average intelligence and literacy levels, such as offender populations.

To describe the FAST in more detail, imagine that we seek to assess whether or not the words ‘child’ and ‘sex’ are related for a sample of contact sex offenders. We could present them with each of four stimuli, individually and in a quasi-random order. The stimuli would consist of the words ‘child’ and ‘sex’ (or various synonyms of these) and two novel and entirely unrelated control words (these may even be nonsense syllables). Upon the presentation of each stimulus, the subject must respond with one of two key presses. A common response to the target words (e.g. ‘child’ and ‘sex’) is reinforced through contingent verbal feedback presented on screen immediatley following responses. In this way, a functional response class can be established for the two target stimuli using trial-by-trial learning. At the same time, an alternative common response is established for the two control stimuli, presentations of which are interspersed among presentations of the target stimuli. The number of trials required for the subject to reach a preset fluency criterion in this block of trials (e.g. 10 successive correct responses) should represent an index of the pre-existing strength of the relation between the words ‘child’ and ‘sex’.

In a second block of training, we can attempt to establish a common response for the word ‘child’ and one of the control words, and another response class for the word ‘sex’ and the remaining control word, using trial-by-trial feedback alone. If the words ‘child’ and ‘sex’ are related in the history of the subject, then this second task block will require a larger number of training trials than the first one. A baseline rate of acquisition of common response functions for a randomly selected set of words can also be recorded for comparison purposes. We could then assess the extent of the relative facilitating or retarding effect of preexisting stimulus relations between ‘child’ and ‘sex’ during the two training blocks. This method can be referred to as a function acquisition speed test (FAST; O'Reilly, et al., Citationin press) precisely because it compares speeds in the the learned acquisition of different functional response classes for pairs of stimuli.

The FAST methodology is already being applied in the analysis of sexual stimulus relations. Specifically, in one recent study (O'Reilly, Roche, Arancibia, & Ruiz, Citation2012), 20 male adult subjects were exposed to three FAST tests in a random order. The tests were designed to measure the existence and strength of preexisting stimulus relations between sexual imagery and images of semiclothed solo female targets of varying ages (Tanner stages 3, 4, and 5, equating to ages 11.5–13, 13–15, and 15+ years, approximately; Tanner, Citation1973). Target images were digitally created images taken from the Not Real People stimulus set (NRP; Laws & Gress, Citation2004), while neutral and generic sexual images were taken from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS; Lang, Bradley, & Cuthbert, Citation1999). In one block of FAST training, subjects were trained to form a functional response class for generic sexual images involving couples in erotic situations and images of solo female targets (i.e. they were taught to press a Z key on the computer keyboard). In another block, a common response was required for nonsexual images and solo female target images (again representing Tanner stages, 3, 4, or 5). This procedure was repeated across three FAST tests, presented in a random order, with the only difference being the age of the target female, which was systemtically varied across FAST tests. Baseline blocks were also administered using entirely neutral stimuli taken from the IAPs.

As expected, a distribution of FAST effects was observed across the three tests, with effect sizes rising from significantly negative (i.e. subjects required more trials to learn a common response function for the ‘child’ and ‘sexual’ stimuli) for Tanner 3 images (prepubertal) to neutral FAST effects for Tanner 4 targets (pubertal), increasing to a near significant positive effect for Tanner 5 images (postpubertal). That is, we observed a socially sanctioned or ‘normal’ FAST test effect only when female targets were postpubertal. These results show that, at the group level, subjects found it difficult to form a functional response class (i.e. produce the same response) for sexual images and images of prepubescent girls. This is indicative of a preexisting and significant incompatibility between stimuli of these two types. However, no such resistance to forming functional response classes between sexual images and semiclothed images of minors was observed when the minors were pubescent, but neither was there facilitation of such functional class formation. That is, functional response classes for sexual and pubescent girl images were formed at the same rate as functional response classes for neutral images and images of pubescent girls. Finally, a near significant positive effect was observed when the solo female targets were postpubescent. That is, subjects reached the learning criterion for producing common responses to sexual images and images of solo postpubescent girls faster than they did for neutral images and images of postpubescent girls (i.e. subjects’ histories facilitated the formation of a response class for postpubertal female stimuli and generic sexual images).

A strength of relation (SoR) index was also calculated using the method outlined by O'Reilly et al. (Citationin press) to provide a single and non-relative metric of the preexisting strength of child-sex stimulus relations between the target age group and sexual images. The mean SoR scores rose from negative to slightly positive to strongly positive from Tanner 3 to 4 to 5 (i.e. as target age increased from pre- to postpubertal), and an analysis of variance showed this relationship to be statistically significant.

Interestingly, these findings parallel those of Gavin et al. (2012) and previous studies using physiological measures in finding that images of children that are not of consenting age (e.g. Tanner 5) in many jurisdictions may nevertheless participate in preexisting implicit relations with sexual stimuli. This study is the first of its kind, however, to map the strength of these associations across age ranges and to confirm, using implicit measures, that minors may be classified as non-sexual for the majority of male participants only when pre pubertal (i.e. rather than on the basis of age of consent laws). Importantly, a near significant level of child-sex association was observed in this preliminary study, across a random sample of male volunteers, for Tanner 5 targets. Females of this age would not have legal rights to provide consent for sexual activity in many jurisdictions. Perhaps of greater interest is that a history of such stimulus association would be very unlikely to emerge from explicit self-report measures.

Conclusion

The analysis of derived stimulus relations has opened up a new vista of research opportunities in the realm of complex human behavior, including that of human sexuality. While these developments are in their infancy, they promise to lead to a thoroughly functional approach to the analysis of complex sexual behavior, both overt and at the level of private cognition. We believe that the analysis of derived stimulus relations represents a paradigm shift for modern behavior analysis and that as a result, the learning approach to human sexual functioning is about to get its second wind.

References

- Abel, G.G., & Becker, J.V. (1985). Sexual interest card sort. Unpublished manuscript.

- Bancroft J. Aversion therapy of homosexuality. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1969; 115: 1417–1432.

- Barnes D. Stimulus equivalence and relational frame theory. The Psychological Record. 1994; 44: 91–124.

- Barnes D. Browne M. Smeets P.M. Roche B. A transfer of functions and a conditional transfer of functions through equivalence relations in three to six year old children. The Psychological Record. 1995; 45: 405–430.

- Barnes-Holmes D. Barnes-Holmes Y. Stewart I. Boles S. A sketch of the Implicit Relational Assessment Procedure (IRAP) and the Relational Elaboration and Coherence (REC) model. The Psychological Record. 2010; 60: 527–542.

- Barnes-Holmes D. Hayden E. Barnes-Holmes Y. Stewart I. The Implicit Relational Assessment Procedure (IRAP) as a response-time and event-related-potentials methodology for testing natural verbal relations: A preliminary study. The Psychological Record. 2008; 58: 497–516.

- Barnes-Holmes D. Hayes S.C. Dymond S. Relational frame theory: A post-Skinnerian account of language and cognition. Hayes S.C. Barnes-Holmes D. Roche B. Plenum Press. New York, 2001

- Blackledge J.T. An introduction to relational frame theory: Basics and applications. The Behaviour Analyst Today. 2003; 3: 421–433.

- Blanton H. Jaccard J. Arbitrary metrics in psychology. American Psychologist. 2006; 61: 27–41.

- Blanton H. Jaccard J. Gonzales P. Christie C. Decoding the implicit association test: Implications for criterion prediction. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2006; 42: 192–212.

- Both S. Laan E. Spiering M. Nilsson T. Oomens S. Everaerd W. Appetitive and aversive classical conditioning of female sexual response. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2008; 5: 1386–1401.

- Brown A.S. Gray N.S. Snowden R.J. Implicit measurement of sexual preferences in child sex abusers: Role of victim type and denial. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment. 2009; 21: 166–180.

- Cliffe M.J. Parry S.J. Matching to reinforcer value: Human concurrent variable-interval performance. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1980; 32: 557–570.

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences2nd ed. Lawrence Earlbaum Associates. Hillsdale NJ, 1988

- Dasgupta N. Greenwald A.G. Banaji M.R. The first ontological challenge to the IAT: Attitude or mere familiarity?. Psychological Inquiry. 2003; 14: 238–243.

- Dawson D.L. Barnes-Holmes D. Gresswell D.M. Hart A.J.P. Gore N.J. Assessing the implicit beliefs of sexual offenders using the Implicit Relational Assessment Procedure: A first study. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment. 2009; 21: 57–75.

- De Houwer J. A structural and process analysis of the Implicit Association Test. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2001; 37: 443–51.

- De Houwer J. What are implicit measures and why are we using them. The handbook of implicit cognition and addiction. Wiers R.W. Stacy A.W. Sage. Thousand Oaks CA, 2006; 11–28.

- De Houwer J. Why the cognitive approach in psychology would profit from a functional approach and vice versa. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2011; 6: 202–209.

- De Jong P.J. van den Hout M.A. Rietbroek H. Huijding J. Dissociations between implicit and explicit attitudes towards phobic stimuli. Cognition & Emotion. 2003; 17: 521–545.

- Diamond M. Jozifkova E. Weiss P. Pornography and sex crimes in the Czech Republic. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2010; 40: 1037–1043.

- Dixon M.R. Rehfeldt R.A. Zlomke K.R. Robinson A. Exploring the development and dismantling of equivalence classes involving terrorist stimuli. The Psychological Record. 2006; 56: 83–103.

- Dymond S. Barnes D. A transformation of self-discrimination response functions in accordance with the arbitrarily applicable relations of sameness, more than, and less than. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1995; 64: 163–184.

- Earls C.M. Castonguay L.G. The evaluation of olfactory aversion for a bisexual pedophile with a single-case multiple baseline design. Behavior Therapy. 1989; 20: 137–146.

- Endrass J. Urbaniok F. Hammermeister L.C. Benz C. Elbert T. Laubacher A. Rosseger A. The consumption of Internet child pornography and violent and sex offending. BMC Psychiatry. 2009; 9: 43–50.

- Fazio R.H. Olson M.A. Implicit measures in social cognition research: Their meaning and use. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003; 54: 297–327.

- Fields L. Adams B.J. Verhave T. Newman S. The effects of nodality on the formation of equivalence class development. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1990; 53: 345–358.

- Feldman M.P. MacCulloch M.J. Homosexual behaviour: Therapy and assessment. Pergamon Press. Oxford England, 1971

- Gannon T.A. Wright D.B. Beech A.R. Williams S. Do child molesters hold distorted beliefs? What does their memory recall tell us?. Journal of Sexual Aggression. 2006; 12: 5–18.

- Gannon T.A. Current cognitive distortion theory and research: An internalist approach to cognition. Journal of Sexual Aggression. 2009; 15: 225–246.

- Gavin A. Roche B. Ruiz M.R. Competing contingencies over derived relational responding: A behavioral model of the Implicit Association Test. The Psychological Record. 2012; 58: 427–441.

- Gawronski B. What does the Implicit Association Test measure? A test of the convergent and discriminant validity of prejudice related IATs. Experimental Psychology. 2002; 49: 171–180.

- Gray N.S. Brown A.S. MacCulloch M.J. Smith J. Snowden R.J. An implicit test of the associations between children and sex in pedophiles. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005; 114: 304–308.

- Greenwald A.G. McGhee D.E. Schwartz J.L.K. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998; 74: 1464–1480.

- Grey I.M. Barnes D. Stimulus equivalence and attitudes. The Psychological Record. 1996; 46: 243–270.

- Hayes S.C. Barnes-Holmes D. Roche B. Relational frame theory: A post-Skinnerian account of human language and cognition. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Press. New York, 2001

- Hoffmann H. Janssen E. Turner S.L. Classical conditioning of sexual arousal in women and men: Effects of varying awareness and biological relevance of the conditioned stimulus. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2004; 33: 43–53.

- Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics. 1979; 6: 65–70.

- Kafka M.P. Hennen J. A DSM-IV Axis I comorbidity study of males (n = 120) with paraphilias and paraphilia-related disorders. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment. 2002; 14: 349–366.

- Kamphuis J.H. De Ruiter C. Janssen B. Spiering M. Preliminary evidence for an automatic link between sex and power among men who molest children. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2005; 20: 1351–1365.

- Karpinski A. Hilton J.L. Attitudes and the Implicit Association Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001; 81: 774–788.

- Keown K. Gannon T.A. Ward T. The effects of visual priming on information processing in child sexual offenders. Journal of Sexual Aggression. 2008a; 14: 145–159.

- Keown K. Gannon T.A. Ward T. What were they thinking? An exploration of child sexual offenders’ beliefs using a lexical decision task. Psychology, Crime & Law. 2008b; 14: 317–337.

- Kohlenberg B.K. Hayes S.C. Hayes L.J. The transfer of contextual control over equivalence classes through equivalence classes: A possible model of social stereotyping. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1991; 56: 505–518.

- Lalumière M.L. Quinsey V.L. Pavlovian conditioning of sexual interests in human males. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1998; 27: 241–252.

- Langevin R. Martin M. Can erotic responses be classically conditioned?. Behavior Therapy. 1975; 6: 350–355.

- Lang, P.J., Bradley, M.M., & Cuthbert, B.N. (1999). International Affective Picture System: Instruction manual and affective ratings. ( Technical Report A-4). Florida: The Center for Research in Psychophysiology, University of Florida.

- Laws D.R. Gress C.L.Z. Seeing things differently: The viewing time alternative to penile plethysmography. Legal and Criminological Psychology. 2004; 9: 183–96.

- Letourneau E.J. O'Donohue W. Classical conditioning of female sexual arousal. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1997; 26: 63–78.

- Lipkens R. Hayes S.C. Hayes L.J. Longitudinal study of the development of derived relations in an infant. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1993; 56: 201–239.

- Lovibond S.H. Conceptual thinking, personality and conditioning. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1963; 2: 100–111.

- Malamuth N.M. Brown L.M. Sexually aggressive men's perceptions of women's communications. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994; 67: 699–712.

- McConaghy N. Subjective and penile plethysmograph responses following aversion relief and apomorphine aversion therapy for homosexual impulses. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1969; 115: 723–730.

- McConaghy N. Penile response conditioning and its relationship to aversion therapy in homosexuals. Behavior Therapy. 1970; 1: 213–221.

- McFarland S.G. Crouch Z. A cognitive skill confound on the Implicit Association Test. Social Cognition. 2002; 20: 483–510.

- McGlinchey A. Keenan M. Dillenburger K. Outline for the development of a screening procedure for children who have been sexually abused. Research on Social Work Practice. 2000; 10: 721–747.

- Mierke J. Klauer K.C. Method-specific variance in the implicit association test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003; 85: 1180–1192.

- Mihailides S. Devilly G.J. Ward T. Implicit cognitive distortions and sexual offending. Sexual Abuse: Journal of Research and Treatment. 2004; 16: 333–350.

- Merwin R.M. Wilson K.G. Preliminary findings on the effects of self-referring and evaluative stimuli on stimulus equivalence class formation. The Psychological Record. 2005; 55: 561–575.

- Moxon P.D. Keenan M. Hine L. Gender role stereotyping and stimulus equivalence. The Psychological Record. 1993; 43: 381–393.

- Nunes K.L. Firestone P. Baldwin M.W. Indirect assessment of cognitions of child sexual abusers with the Implicit Association Test. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2007; 34: 454–475.

- Ó Ciardha, C., & Gannon, T.A. (2011). The cognitive distortions of child molesters are in need of treatment. Journal of Sexual Aggression. 17, 130–141.

- Ó Ciardha, C., & Gormley, M. (in press). Using a pictorial modified Stroop task to explore the sexual interests of sexual offenders against children. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment.

- Olson M.A. Fazio R.H. Relations between implicit measures of prejudice: What are we measuring?. Psychological Science. 2003; 14: 636–639.

- O'Reilly, A., Roche, B., Ruiz, M., Ryan, A., & Campion, G. (accepted). A Function Acquisition Speed Test for equivalence relations (FASTER). The Psychological Record.

- O'Reilly, A., Roche, B., Ruiz, M. R., Tyndall, I. & Gavin, A. (In press). The Function Acquisition Speed Test (FAST): A behavior-analytic implicit test for assessing stimulus relations. The Psychological Record .

- O'Reilly, A., Roche, B., Arancibia, G., & Ruiz, M.R. (2012, May 26–30). Using the Function Acquisiton Speed Test (FAST) in forensic and sex research. Paper presented at the annual convention of the Association for Behavior Analysis International, Seattle, Washington, DC.

- Ottaway S.A. Hayden D.C. Oakes M.A. Implicit attitude and racism: Effect of word familiarity and frequency on the Implicit Association Test. Social Cognition. 2001; 19: 97–144.

- Plaud J.J. Martini J.R. The respondent conditioning of male sexual arousal. Behavior Modification. 1999; 23: 254–268.

- Quayle E. Taylor M. Paedophiles, pornography and the Internet: Assessment issues. British Journal of Social Work. 2002; 32: 863–875.

- Quayle E. Taylor M. Model of problematic Internet use in people with a sexual interest in children. CyberPsychology & Behavior. 2003; 6: 93–106.

- Quayle E. Erooga M. Wright L. Taylor M. Harbinson D. Only pictures? Therapeutic approaches with internet offenders. Russell House Publishing. Lyme Regis, 2006

- Quinn J.T. Harbison J. McAllister H. An attempt to shape penile responses. Behavior Research and Therapy. 1970; 8: 27–28.

- Rachman S. Sexual fetishism: An experimental analogue. The Pychological Record. 1966; 16: 293–296.

- Rachman S. Hodgson R.J. Experimentally-induced “sexual fetishism”: Replication and development. Psychological Record. 1968; 18: 25–27.

- Reese H.W. The perception of stimulus relations: Discrimination learning and transposition. Academic Press. San Deigo CA, 1968

- Ridgeway I. Roche B. Gavin A. Ruiz M.R. Establishing and eliminating IAT effects in the laboratory: Extending a behavioral model of the Implicit Association Test. European Journal of Behavior Analysis. 2010; 11: 133–150.

- Roche B. Barnes D. Arbitrarily applicable relational responding and sexual categorization: A critical test of the derived difference relation. The Psychological Record. 1996; 46: 451–475.

- Roche B. Barnes D. A transformation of sexual arousal functions in accordance with arbitrarily applicable relations. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1997; 67: 275–301.

- Roche B. Barnes D. The experimental analysis of human sexual arousal: Some recent developments. The Behavior Analyst. 1998; 21: 37–52.

- Roche B. Barnes-Holmes D. Smeets P.M. Barnes-Holmes Y. McGeady S. Contextual control over derived transformation of discriminative and sexual arousal functions. The Psychological Record. 2000; 50: 267–291.

- Roche B. Barnes-Holmes Y. Barnes-Holmes D. Stewart I. O'Hora D. Relational Frame Theory: A new paradigm for the analysis of social behavior. The Behavior Analyst. 2002; 25: 75–91.

- Roche B. Dymond S. A transformation of functions in accordance with the non-arbitrary relational properties of sexual stimuli. The Psychological Record. 2008; 58: 71–90.

- Roche B. Ruiz M. O'Riordan M. Hand K. A relational frame approach to the psychological assessment of sex offenders. Viewing child pornography on the Internet: Understanding the offence, managing the offender, and helping the victims. Taylor M. Quayle E. Russell House Publishing. DorsetUK, 2005; 109–125.

- Roche, B., & Quayle, E. (2007). Sexual disorders. InJ.Wood & J.Kanter, Understanding behavior disorders: A Contemporary behavioral perspective. (pp. 341–368.). Reno. NV: Context Press.

- Rosen R.C. Kopel S.A. Penile plethysmography and bio-feedback in the treatment of a transvestite-exhibitionist. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1977; 45: 908–916.

- Rosen R.C. Shapiro D. Schwartz G. Voluntary control of penile tumescence. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1975; 37: 479–483.

- Rothermund K. Wentura D. Underlying processes in the Implicit Association Test (IAT): Dissociating salience from associations. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2004; 133: 139–165.

- Seto M.C. Cantor J.M. Blanchard R. Child pornography offenses are a valid diagnostic indicator of pedophilia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006; 115: 610–615.

- Schaefer H.H. Colgan A.H. The effect of pornography on penile tumescence as a function of reinforcement and novelty. Behavior Therapy. 1977; 8: 938–946.

- Schauss S.L. Chase P.N. Hawkins R.P. Environment–behavior relations, behavior therapy, and the process of persuasion and attitude change. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1997; 28: 31–40.

- Sherman S.J. Rose J.S. Koch K. Presson C.C. Chassin L. Implicit and explicit attitudes toward cigarette smoking: The effects of context and motivation. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2003; 22: 13–39.

- Sidman M. Reading and auditory-visual equivalences. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1971; 14: 5–13.

- Sidman M. Functional analysis of emergent verbal classes. Analysis and integration of behavioral units. Thompson T. Zeiler M.D. Erlbaum. Hillsdale NJ, 1986; 213–245.

- Snowden R. Wichter J. Gray N. Implicit and explicit measurements of sexual preference in gay and heterosexual men: A comparison of priming techniques and the implicit association task. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008; 37: 558–565.

- Tanner J.M. Growing up. Scientific American. 1973; 229: 34–43.

- Taylor M. Quayle E. Child pornography: An internet crime. Routledge. Brighton, 2003

- Ward T. Sexual offenders’ cognitive distortions as implicit theories. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2000; 5: 491–507.

- Ward T. Casey A. Extending the mind into the world: A new theory of cognitive distortions in sex offenders. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2010; 15: 49–58.

- Watt A. Keenan M. Barnes D. Cairns E. Social categorisation and stimulus equivalence. The Psychological Record. 1991; 41: 33–50.