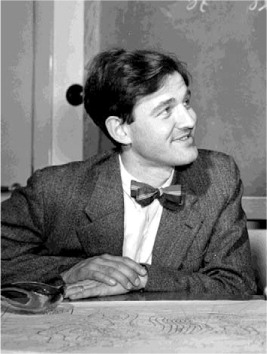

Bert Richard Johannes Bolin was born on 15 May 1925 in Nyköping, Sweden. He died on 30 December 2007 in Stockholm. Both his parents were teachers. His father, Richard Bolin, was very interested in weather phenomena, and he inspired Bert Bolin to study meteorology after he finished school. His father took him to the headquarters of the Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute in 1942 and discussed the prospects for the young man with Dr. Anders Ångström, the deputy Director. The following year, Bolin began studying mathematics and physics at the University of Uppsala and also attended Professor Hilding Köhler's lectures in meteorology. After his BSc degree in 1946, Bolin moved to Stockholm.

During a year in military service in Stockholm in 1947, Bolin came into contact with Professor Carl-Gustaf Rossby who had then been asked to return from the US to build up the study of meteorology in Sweden. In a short time, Rossby was able to create the International Meteorological Institute in Stockholm (IMI), in association with the Department of Meteorology at Stockholm University, and to gather a very qualified group of scientists, mainly from Europe. In this stimulating environment, Bolin pursued his studies and obtained an MSc degree in 1950. Later that year, he went on to spend a year at the University of Chicago and the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton University in the USA where he came in contact with Jule Charney, Joseph Smagorinsky, Norman Phillips, John von Neumann and other top scientists in the field of meteorology and numerical weather prediction. After his return to Stockholm in 1951, Bolin started working towards his PhD in interaction with a growing number of researchers working at or visiting the Institute, including Bo Döös, Pierre Welander, Aksel Wiin-Nielsen, Arnt Eliassen, Erik Palmén, Chester Newton, Philip Thompson and several others. During a very productive period Bolin wrote a number of important papers on atmospheric circulation patterns and on the basis for numerical weather forecasting. The first operational numerical weather forecasting in the world was carried out by the group around IMI-founder Rossby in 1954.

Bolin received his PhD degree from Stockholm University in 1956 (); his thesis dealt with the interaction between wind and pressure fields and its application to numerical weather prediction. In his report to the Faculty Board, the Faculty Opponent Professor Norman Phillips from Princeton University wrote, ‘Mr Bolin's defence of his thesis must be considered as extremely competent. He not only demonstrated a complete comprehension of the relevant physical and mathematical ideas, but was also able to present them in an extremely logical and convincing fashion’.

Bolin soon became a key staff member at IMI and the University Department of Meteorology and was given several important tasks, including the running of the scientific journal Tellus – then published by the Swedish Geophysical Society. When Rossby left for the USA on a sabbatical year in 1957, Bolin was placed in charge of the Institute. Soon after his return to Stockholm in 1957, Rossby suddenly died and Bolin was considered the natural successor. With able assistance from other staff members, including Pierre Welander and Erik Eriksson, he took over the leadership of the Institute. It took a few more years until the University acquired a permanent chair in meteorology – Rossby's professorship was a personal one. In 1961, Bolin became the first holder of the new position which he then held for almost 30 years.

Earlier in his career – soon after completing his PhD – Bolin was advised by Rossby to broaden his interest to include atmospheric chemistry and biogeochemical cycles. This was the beginning of his lasting and influential research on the carbon cycle including processes in the atmosphere, oceans and biosphere. He played an important role as promoter of atmospheric chemistry measurements of carbon dioxide as well as of ionic components in precipitation. In 1959, he published, together with Erik Eriksson, an estimate of how much the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere would increase by the year 2000 if the emissions were not controlled. It should be noted that this prediction was made before any increase in the concentration of carbon dioxide had been clearly documented. His estimate turned out to be surprisingly realistic.

Between 1965 and 1967 Bolin spent almost two years as Scientific Director of the European Space Research Organisation in Paris, where he was mainly concerned with the coordination of the scientific interests in the initial development of the early European satellites and the planning of a permanent rocket-launch site at Kiruna in northernmost Sweden. During this period, Döös acted as Director of IMI and Professor in the University Department.

In the mid-1960s, Bolin became deeply involved in the creation of the Global Atmospheric Research Programme (GARP) which was developed within the framework of ICSU after an initiative (in 1962) by Jule Charney. This effort was stimulated by the success of numerical weather prediction and the prospects of using meteorological satellites for a further improvement. GARP was aimed at providing a better understanding of global weather systems in order to enable improved predictions of weather and climate. The real starting point of GARP was a very successful planning conference held at Skepparholmen close to Stockholm in 1967 at which Bolin played a major role as organiser and motivator. It was a very natural choice when he was chosen as the first chairman of the Joint Organising Committee for GARP set up later that same year jointly by the International Council of Science (ICSU) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). Many other leading atmospheric scientists were also involved in the creation of GARP and have contributed to it and to its successor, the World Climate Research Programme (WCRP), over the years. However, there is no doubt that Bolin made a fundamental contribution to the organisation of international cooperation in weather and climate research. Indeed, the first major planning effort for global climate research was organised in 1974 at Wik, close to Stockholm, with Bolin as organiser and chairman.

In the late-1960s, the acidification problem began to be revealed, to a large degree because of pioneering work by Svante Odén at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences in Uppsala. During the period 1961–1963, as a visitor to IMI, Odén analysed precipitation chemistry data collected by Erik Eriksson and his colleagues and he noticed a systematic change in the chemical climate with increasing amounts of sulphur and a lowering of the pH level. These results were first made public at a conference organised by the Swedish Natural Science Research Council in 1967.

On the initiative of Bolin, the acidification problem was chosen as the topic of Sweden's Case Study to the UN Conference on the Human Environment, held in Stockholm in 1972. Under Bolin's inspiring leadership, a group of scientists, including among others Odén, Carl Olof Tamm, Lennart Granat and Henning Rodhe, prepared the first comprehensive, integrated assessment of the acidification problem. The case study included a description both of long-range transport of acidifying pollutants and of their effects on terrestrial and limnic ecosystems (Bolin et al., 1972). It is not surprising that the report describing a completely new concept was met with some scepticism. Bolin's factual and passionate defence of the new ideas went a long way to convincing the critics.

ICSU's Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment (SCOPE) is another organisation that greatly benefitted from Bolin's competence. He played a leading role in its project on biogeochemical cycles and acted as editor of four major SCOPE reports, the most well-known being Report No. 13 (1979): The Global Carbon Cycle and Report No. 29 (1986): The Greenhouse Effect, Climatic Change, and Ecosystems. This latter review formed the basis for the much-quoted conclusions regarding the prospects for climate change reached by scientists and politicians at a meeting in Villach, Austria, in 1985.

During the 1980s, a need had become more and more evident for a deeper collaboration between geoscientists (meteorologists, oceanographers, hydrologists, geologists, etc.) and biologists (ecologists, microbiologists, etc.) in advancing our understanding of the global environmental system and of the way mankind was now imposing fundamental changes of it. This led to the formation of one of the largest international research efforts ever undertaken: The International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme (IGBP). Bolin chaired an ICSU working group during the years 1985–86, which led to the decision by ICSU in 1986 to launch this major programme. Bolin's broad scientific knowledge and unique organisational talent made him a central personality in the continued work of IGBP.

The latest and, most likely, the most important contribution of Bolin on the international scene was his key role in the creation of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), set up by WMO and UNEP in 1988, and the leadership exercised by him as chairman of the Panel between 1988 and 1997. The panel was charged with the task to assess:

the physical science basis of climate change;

the climate change impacts, adaptation and vulnerability; and

the options for mitigation of climate change.

The first assessments published in 1990 served as the basis for the negotiations leading up to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) signed by a great majority of the World's nations at the UN Conference on Environment and Development held in Brazil in 1992. Similarly, the second assessment of IPCC, which was made official in 1995, provided the main scientific input to the protocol to the UNFCCC agreed upon in Kyoto in 1997. Subsequent assessments have been published in 2001, 2007 and 2013/2014 ().

Many scientists and policy makers have testified to Bolin's absolutely fundamental contributions to the IPCC process, e.g. Kjellén (Citation2009) and Watson (Citation2008). His own account of how the science of climate change and its interaction with politics have developed over the past almost 200 years, with focus on the IPCC period, can be found in A History of the Science and Politics of Climate Change: The Role of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Bolin, Citation2007).

At the national (Swedish) level, Bolin has played a no less important role. It would be too much to try to mention all his contributions in this context, however, some notable points are that he had been a very active member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences since 1962, the Swedish Natural Science Research Council from 1971 to 1980 and the Scientific Advisory Board to the Swedish Government from 1983 to 1986. Between 1986 and 1988, he served as advisor on science policy to the Prime Minister of Sweden. He served as Dean of the Faculty of Sciences at Stockholm University and was a member of various committees at the University, the National Environment Protection Board, etc.

Bolin was a great scientific leader and inspiration for his students and fellow scientists, not only those in his home department at Stockholm University but also for the global community of climate scientists. Wherever he became engaged, at the national level as well as internationally, he was the natural and unquestioned leader.

The following qualities, I believe, made Bolin such an influential leader:

He made a solid scientific career, which made him credible and respected as a scientist.

The breadth of his knowledge, including not only atmospheric and ocean sciences but also biogeochemistry and social science.

His ability to see the big picture, to summarise and to synthesise.

His diplomatic talent.

His community involvement and his desire to practically apply research results.

Bolin was a member of some 10 scientific academies and learned societies round the world, including the Royal Society in the UK, and the National Academies in Russia, India and the United States. He received numerous prestigious awards and prizes including the International Meteorological Organisation Prize (1981), the Carl-Gustaf Rossby Research Medal of the American Meteorological Society (1984), the Tyler Prize of the University of Southern California (1988), the Milankovic Medal by the European Geophysical Society (1994), the Blue Planet Prize of Asahi Glass Foundation (1995) and the Svante Arrhenius Medal in Gold of the Royal Swedish Academy of Science (2000).

In the present context, it is also pertinent to emphasise Bolin's contributions as Executive Editor of Tellus between 1952 and 1957, and as Editor-in-Chief between 1958 and 1983. After the division of the journal into two series in 1983, Bolin remained Editor-in-Chief of the A-series (Dynamic Meteorology and Oceanography) until his retirement in 1990, while Henning Rodhe became Editor of the B-series (Chemical and Physical Meteorology). Under Bolin's able guidance, the journal has maintained a high scientific standard during his lifetime and remained one of the main international journals in the field of atmospheric and oceanic sciences.

As the Director of the International Meteorological Institute in Stockholm until 1990 and later as an active emeritus, Bolin saw many visitors from abroad come and spend periods of varying length at the institute. Frequent visitors during the later years of his life were Robert Charlson, Paul Crutzen, Lennart Bengtsson, James Holton, Berrien Moore, Ray Pierrehumbert, Jost Heintzenberg and many others.

With all these external activities, how much was he seen by colleagues and students in his home department at Stockholm University? It is true that he was frequently away, but when he was ‘at home’ his presence was very stimulating indeed. You could walk into his office or meet him in the coffee room and bring up a scientific or organisational problem. In a very short time, Bolin grasped the question, reformulated it in a more precise way and offered a solution that often turned out to be fruitful and forward looking. His lectures and seminars were always extremely stringent and he had the rare ability to transmit his enthusiasm for the subject to the listener.

Bolin supervised some 10 PhD students among them Aksel Wiin-Nielsen, Bo Döös, Ingemar Holmström, Georg Witt, Hilding Sundqvist, Henning Rodhe, Paul Crutzen, Lennart Granat, Anders Bjökström and Kim Holmén.

On a personal note, when IPCC – together with former US Vice-President Al Gore – received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007, Bolin was of course delighted. He was invited to attend the Prize ceremony in Oslo on 10 December. It had even been suggested that he should be the one to step forward to receive the prize on behalf of IPCC, although it was 10 years since he had stepped down as its chairman. Unfortunately, his ailing health prevented him from travelling to Oslo. Instead he and his Monica watched the ceremony on TV in our apartment (). It was a very special moment for me and my wife to be with on this important occasion and to hear him commenting on the speeches of Al Gore and Rajendra Pachauri – the current chairman of IPCC. Soon after the ceremony Bolin contacted both of them by phone to congratulate them. When Al Gore and Rajendra Pachauri a day later visited Stockholm to speak in the House of Parliament, Bolin met with them and handed over copies of his recently published book.

Bolin remained actively engaged in the climate change debate until the very last days of his life. In fact, his last publication, co-authored with Swedish Ambassador Bo Kjellén, appeared in the Swedish Daily Newspaper Svenska Dagbladet on 2 January 2008, three days after Bolin's death. The title of this opinion piece was ‘Serious but not hopeless’ – an eloquent testimony of Bolin's lasting message to us all.

For a more detailed and personal account of Bolin's scientific career, the reader is referred to an interview made by Hessam Taba, published in WMO Bulletin, vol. 37, No. 4 (October), 1988.

The following list of 37 papers was selected by Bolin himself as his most significant publications. A complete list containing 190 items can be found in the supplementary material: http://www.tellusb.net/index.php/tellusb/rt/suppFiles/20583/0.

Berggren, R., Bolin, B. and Rossby, C.-G. 1949. An aerological study of zonal motion, its perturbations and break-down. Tellus 1(2), 14–37.

Bolin, B. 1950. On the influence of the earth's orography on the general circulation of the Westerlies. Tellus 2(3), 184–195.

Bolin, B. 1952. The general circulation of the atmosphere. Advances in Geophysics 1, Academic Press, New York.

Bolin, B. 1953. The adjustment of a non-balanced velocity field towards geostrophic equilibrium in a stratified fluid. Tellus 5, 373–385.

Bolin, B. 1955. Numerical forecasting with the barotropic model. Tellus 7, 27–49.

Bolin, B. 1956. An improved barotropic model and some aspects of using the balance equation for three-dimensional flow. Tellus 8, 61–75.

Bolin, B. and Eriksson, E. 1959. Changes in the carbon dioxide content of the atmosphere and sea due to fossil fuel combustion. In: The Atmosphere and the Sea in Motion. Scientific contribution to The Rossby Memorial Volume (ed. B. Bolin), The Rockefeller Institute Press, New York, pp. 130–142.

Bolin, B. Note on the exchange of iodine between the atmosphere, land and sea. lnternational Journal of Air Pollution 2(23), 127–131.

Bolin, B. Atmospheric chemistry and broad geophysical relationships. Proceedings of US National Academy of Sciences, 45(12), 1663–1672.

Bolin, B. 1960. On the exchange of carbon dioxide between the atmosphere and the sea. Tellus 12, 274–281.

Bolin, B. and Stommel, H. 1961. On the abyssal circulation of the world ocean, IV. Origin and rate of circulation of deep ocean water as determined with the aid of tracers. Deep-Sea Res. 8, 95–110.

Bolin, B. 1962. Transfer and circulation of radioactivity in the atmosphere. Nuclear radiation in geophysics (eds. H. Israel and A. Krebs), Academic Press, New York, pp. 136–168.

Bolin, B. and Keeling, C. D. 1963. Large-scale atmospheric mixing as deduced from the seasonal and meridional variations of carbon dioxide. J. Geophys. Res. 68, 3899–3920.

Keeling, C. D. and Bolin, B. 1967. The simultaneous use of chemical tracers in oceanic studies, I. General theory of reservoir models. Tellus 19, 566–581.

Bolin, B. 1964. Gross-atmospheric circulation of the atmosphere as deduced with the aid of tracers. In: Research in Geophysics. Vol. 2. Solid Earth and Interface Phenomena. MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass., pp. 478–508.

Keeling, C. D. and Bolin, B. 1968. The simultaneous use of chemical tracers in oceanic studies, II. A three-reservoir model of the North and South Pacific Oceans. Tellus 20, 17–54.

Bolin, B. and Bischof, W. 1970. Variations of the carbon dioxide content of the atmosphere in the northern hemisphere. Tellus 22, 431–42.

Bolin, B., Granat, L., Ingelstam, L., Johannesson, M., Mattson, E. and co-authors. 1972. Air pollution across national boundaries: the impact on the environment of sulfur in air and precipitation. Sweden's Case Study for the UN Conf. on the Human Environment. Royal Ministry for Foreign Affairs and Royal Ministry of Agriculture, Stockholm, 96 pp.

Bolin, B. The global atmospheric research programme. A co-operative effort to explore the weather and climate of our planet. GARP Report, No. 1, 28 pp., WMO, Geneva.

Bolin, B. 1972. Atmospheric chemistry and environmental pollution. In: Meteorological challenges: a history (ed. D. P. McIntyre), pp. 237–266.

Bolin, B. and Rodhe, H. 1973. A note on the concepts of age distribution and transit time in natural reservoirs. Tellus 25, 58–62.

Bolin, B. 1975. A critical appraisal of models for the carbon cycle. In: The physical basis of climate and climate modelling. Report of the International Study Conference in Stockholm, 29 July–10 August 1974. Appendix 8, WMO/GARP Publications series No. 16, pp. 225–235.

Bolin, B. and Charlson, R. J. 1976. On the role of the tropospheric sulfur cycle in the shortwave radiative climate of the earth. Ambio 5, 47–54.

Bolin, B. 1977. Changes of land biota and their importance for the carbon cycle. Science 196, 613–615.

Bolin, B., Degens, E. T., Duvigneaud, P. and Kempe, S. 1979. The global biogeochemical carbon cycle. In: The global carbon cycle (eds. B. Bolin, E. T. Degens, S. Kempe and P. Ketner) SCOPE 13, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, pp. 1–56.

Bolin, B. 1980. Climatic changes and their effects on the biosphere. Fourth IMO Lecture 1979, WMO No. 542, Geneva, 49 pp.

Bolin, B. 1983. Changing global biogeochemistry. In: Oceanography. The present and future (ed. P. G. Brewer), Springer-Verlag, New York, pp. 305–326.

Bolin, B., Björkström, A., Holmén, K. and Moore, B. 1983. The simultaneous use of tracers for ocean circulation studies. Tellus 35B, 206–236.

Bolin, B. 1984. Biogeochemical processes and climate modelling. In: The global climate (ed. J. T. Houghton), Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, UK, 213–223.

Bolin, B. 1986. How much CO2 will remain in the atmosphere? The carbon cycle and projections for the future. In: The greenhouse effect, climatic change, and ecosystems (eds. B. Bolin, B. R. Döös, J. Jäger and R. A. Warrick), SCOPE 29, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, pp. 93–155.

Bolin, B., Jäger, J. and Döös, B. R. 1986. The greenhouse effect, climatic change, and ecosystems. A synthesis of present knowledge. In: The greenhouse effect, climatic change, and ecosystems (eds. B. Bolin, B. R. Döös, J. Jäger and R. A. Warrick), SCOPE 29, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, pp. 1–32.

Moore, B., Bolin, B., Björkström, A., Holmén, K. and Ringo, C. 1989. Ocean carbon models and inverse methods. In: Oceanic circulation models: combining data and dynamics (eds. D. L. T. Anderson and J. Willebrand), Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, pp. 409–449.

Bolin, B. 1989. Changing climates. In: The fragile environment (eds. L. Friday and R. Laskey), Cambridge University Press, UK, pp. 127–147.

Bolin, B. 1990. Key note address at the White House Conference on Science and Economics Research Related to Global Change, April 17–18, 1990, Washington, DC.

Bolin, B. and Fung I. 1992. The global carbon cycle revisited. In: (ed. Ojima). Modelling the Earth System, OIES Global Change Institute, UCAR Office for Interdisciplinary Research, Boulder, Colorado, pp. 151–164.

Bolin, B. 1998. The Kyoto negotiations on climate change: a scientific perspective. Science 279, 330–331.

Bolin, B. and Kheshgi, H. S. 2001. On strategies for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 98, 4850–4854.

Bolin, B. 2007. A History of the Science and Politics of Climate Change. The Role of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 277 pp.

Published Articles and Books by Bert Bolin

Download PDF (442 KB)Acknowledgements

Some parts of this paper has been reproduced from: Rodhe, H. 1991. Bert Bolin and his scientific career. Tellus 43AB, 3–7.

References

- Bolin B . A History of the Science and Politics of Climate Change. The Role of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2007; Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 277.

- Bolin B , Granat L , Ingelstam L , Johannesson M , Mattson E , co-authors . Air pollution across national boundaries: The impact on the environment of sulphur in air and precipitation. Sweden's Case Study for the UN Conference on the Human Environment. 1972; Stockholm: Royal Ministry for Foreign Affairs and Royal Ministry of Agriculture. 96.

- Kjellén B . A New Diplomacy for Sustainable Development: The Challenge of Global Change. 2009; Routledge, New York.

- Watson B . Obituary. Nature. 2008; 451: 642.