Abstract

Media representations are important sources of information especially about contexts that people have limited access to (such as the one we address here, that is, elderly care). Representations of this also give us an insight into how ethnicity-, culture-, and migration-related issues are regarded. This article aims to shed light on media representations related to the nexus of elderly care, ethnicity, and migration in Sweden and Finland, given that the two countries have similar elderly care regimes but different migration regimes. The study uses quantitative content analysis to analyze all of the daily newspaper articles on elderly care that have touched upon these issues and have been published in one major newspaper in each country between 1995 and 2011 (N=347). In this article, we present the topics that these newspaper articles discuss; the elderly care actors that the articles focus on (i.e. whether the focus has been on elderly care recipients, elderly care providers or informal caregivers); the ethnic backgrounds of those who expressed themselves in the articles (i.e. whether the focus has been on the ethnic majority or on ethnic minorities); and the type of explanatory frameworks used in the daily press reporting in question. The article problematizes the media representations of ethnicity- and migration-related issues within the Swedish and Finnish elderly care sectors that the analysis has unveiled in relation to the debate on the challenges that the globalization of international migration poses to the elderly care sector.

The study upon which this article is based got its inspiration from the ongoing debate on the impact that the globalization of international migration will have on elderly care sectors across the world (Nordberg, Citation2012; Torres, Citation2012; Torres & Lawrence, Citation2012). This debate has brought attention to the implications that the increased diversity of ethno-cultural backgrounds among elderly care recipients in European countries will have on the way in which elderly care policy is formulated and elderly care services are delivered (Forssell, Torres, & Olaison, Citation2013; Torres, Citation2012, Citation2013; Warnes, Friedrich, Kellaher, & Torres, Citation2004). This debate has also brought attention to the elderly care sector's increasing reliance on care workers with migrant backgrounds, the challenges that these workers face, and the ones that they pose to the deliverance of user-friendly care (Kofman, Citation2012; Misra, Woodring, & Merz, Citation2006; Wrede & Näre, Citation2013). As such, this debate has put ethnicity- and migration-related issues on the agenda of elderly care policy makers, planners, and providers across Europe.

Drawing on research on media representations in the daily press (which van Dijk, Citation1993, called an “elite discourse”), this article focuses on the ways in which newspaper articles focusing on elderly care in Sweden and Finland report on these issues. The reason for us to focus on media representations is that research has shown that the way in which media writes about migrants and migration has a considerable influence on how members of the ethnic majority view ethnic minorities and people born abroad (see, e.g. Atuel, Seyranian, & Crano, Citation2007; Gardikiotis, Martin, & Hewstone, Citation2004; Littlefield, Citation2008; Stewart, Pitts, & Osborne, Citation2011; van Sterkenburg, Knoppers, & de Leeuw, Citation2010). According to van Dijk (Citation1987), many people who have no personal experience of ethnic minority groups rely on media images (clear support for this has been provided by, e.g. Hartmann and Husband, Citation1974). Research on media representations of ethnic minorities and migrants has shown that the media play a significant role in shaping how people imagine how migrants “are” and how they “behave,” what people associate ethnicity with and in what ways they believe migration can influence society (cf. Ferguson, Citation1998; King and Wood, Citation2001; Miller, Citation1994). Given the great influence the media seem to have, the overall aim of the study is to shed light on the ways in which the daily press in two Nordic countries—with similar elderly care regimes, but dissimilar migration regimes—write about ethnicity- and migration-related issues in their reports on elderly care. The article addresses the following research questions: What are the main topics that the newspaper articles studied discuss? Which elderly care actors are do they focus on (i.e. do the articles focus on elderly care recipients, elderly care providers or informal caregivers)? What are the backgrounds of the elderly care actors that the articles focus on (i.e. are they members of the ethnic majority of these countries or do they belong to the minority—are they migrants)? And what type of explanatory frameworks does the newspaper articles analyzed use?

THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTIVIST PERSPECTIVE AND MEDIA RESEARCH ON ETHNIICITY AND MIGRATION

This study is informed by the social constructivist perspective and the media and communications research that shows that the media plays an important role in constructing attitudes toward various groups of people and phenomena (cf. Barker, Citation2000; Hall, Citation1997). More specifically, the study is tied to a research tradition that has elucidated how representations of migrants and ethnic minorities are constructed in the daily press (van Dijk, Citation1987, 1993). However, in contrast to a number of previous studies—such as Caldas-Coulthard's (Citation2003) study on British and Brazilian daily newspapers’ representations of “the Other”; Gardikiotis et al. (Citation2004) study on representations of ethnic majorities and minorities in British daily newspaper headlines; a similar study by Atuel et al. (Citation2007) but focusing on the US daily press; Grzymala-Kazlowska's (Citation2009) study of how immigrants are represented in Polish daily newspapers; Cisnero's (Citation2008) study on US media representations of immigration; several studies on media representations of immigrants in Sweden (e.g. Bredström, Citation2002, Citation2003; Brune, Citation2002, Citation2004, Citation2006, Citation2008; Dahlsted, Citation2004; Elsrud & Lalander, Citation2007; Pred, Citation2000); studies on media representations in Finland (e.g. Haavisto, Citation2011; Horsti, Citation2008; Nordberg, Citation2006, Citation2007)—the study presented here is not about general representations in the daily press. Instead, we have chosen to limit our investigation to looking at the messages conveyed in articles with ethnicity- and migration-related issues within the Swedish and Finnish elderly care sectors.

The primary reason for this focus is—as already stated—that the impact of the globalization of international migration on elderly care has come to be the subject of an increasingly intense societal debate, in the wake of an aging population with greater care needs as well as the ethnic diversification of both recipients and providers of elderly care (cf. Nordberg, Citation2012; Torres, Citation2012, Citation2013; Wrede & Näre, Citation2013). Given these developments and the research showing the importance of media representations for how people conceive of their surroundings, it would seem interesting to look at the content of representations in the daily press. Starting from a social constructivist perspective, the present study presupposes that, in every time period and context, there is a certain repertoire of categories at people's disposal that explicitly or implicitly confirm a given picture of reality (Burr, Citation1995; Gergen, Citation1995; Sarbin & Kitsuse, Citation1994). Thus, we adhere to the social constructivist tradition, according to which one of the most important tasks of the social sciences is to study how attitudes are produced rather than to determine whether these attitudes correctly represent an external reality.

THE SWEDISH AND FINNISH ELDERLY CARE AND MIGRATION REGIMES

To provide a broader insight into the contexts in focus, we present research on migration regimes and elderly care regimes. This research positions the Swedish and Finnish daily press reporting on migration and elderly care in a broader perspective, thereby also illustrating the topicality of the object of study. The point of departure is the discussion on care regimes that has been pursued during the past two decades as part of a feminist critique of Esping-Andersen's (Citation1990) much-discussed book on several welfare states. This discussion has concerned these welfare states’ ways of organizing their care services and the gender power orders found in family and working life (see, e.g. Anttonen & Sipilä, Citation1996; Pfau-Eiffinger, Citation2005). The gist of the matter has been the argument that care regimes can be differentiated based, among others, on their mixture of formal versus informal care provision, their expectations for the family and how their elderly care sector is organized. In this connection, it is germane to provide two examples of researchers who have tried to define different care regimes. For instance, Anttonen and Sipilä (Citation1996) focused on social services and found two distinct care regimes: a Scandinavian regime characterized by a strong formal sector and a southern European regime characterized by strong reliance on the family. Along the same lines, but focusing on the mixture of formal versus informal care, Bettio and Plantenga (Citation2004) suggested that it is possible to distinguish between countries that expect the family to assume responsibility for care (e.g. Italy, Greece and Spain); countries that place responsibility on the family, but that have different strategies for care of children and care of older people (e.g. Great Britain and the Netherlands); countries that expect a great deal of the family but that provide formal compensation for this (e.g. Austria and German); and, finally, the Nordic countries, which allocate a comparatively large amount of resources to the formal care sector. As we can see, the debate on care regimes has been ongoing for some time. There is no real consensus as to which factors should be used to differentiate the various care regimes, but there is some agreement on the notion that the elderly care models in the Nordic countries are so similar that they can be conceived of as belonging to the same elderly care regime (see both Anttonen & Sipilä, Citation1996 and Bettio, Simonazzi, & Villa, Citation2006), although some between-country differences have been pointed out (see, e.g. Szebehely, Citation2005). In light of the above, we will talk about there being a common Swedish and Finnish elderly care regime.

Another relationship emerges, however, when we consider the research on migration regimes, which is the term used to capture a country's orientation to immigration policies and migration history, to how rules of citizenship are constructed, to what conceptions of “nation” look like, and to how the diversity implied in immigranthood should be dealt with (see, e.g. Koslowski, Citation1998; Lutz, Citation2008; Williams, Citation2005; Williams & Gavanas, Citation2008). The discussion on the Nordic countries’ various migration regimes has not been as exhaustive as that on these countries’ care regimes. However, if we consider how the Nordic countries’ often-dissimilar immigration histories, immigration policies, and strategies regarding diversity have developed, it would seem rather unreasonable to talk about a single Nordic migration regime. The simple fact that 15% of Sweden's population (SCB, Citation2012), as opposed to 4.5% of Finland's (Statistikcentralen, Citation2012a), was born abroad supports this assumption. The differences between countries’ migration regimes are related in part to the patterns of migration to these countries over the years, and to how migration policies have been framed in the context of the local labor markets. In contrast to Sweden, which has been a country of immigration since the 1960s, Finland was a country of emigration right up until the 1980s. It was not until then that Finland experienced a migration surplus. This surplus increased rapidly, and the proportion of inhabitants with a migrant background grew by a factor of five from 1988 to 1997 (CitationStatistikcentralen, 2012a). Relatively speaking, this meant a great adjustment. Early immigration to Finland consisted of reception of refugees, return migration of Finnish people settled abroad and immigration based on marriage or studies, while Sweden has primarily experienced labor immigration, reception of refugees and to some extent family reunification immigration. Since 2006, however, Finnish migration policy has been more instrumental in focus, with a strong emphasis on labor-related immigration (Helander, Citation2011; Wrede & Nordberg, Citation2010). Despite the increased influx of immigrants, the absolute number of individuals with an immigrant background is still low in Finland. In 2011, 4.5% of people living in Finland had a native language other than the national languages, and 3.4% of the inhabitants were non-Finnish citizens (the largest groups coming from neighboring countries). Estonian citizens amounted to 20.3% and Russian citizens to 15.4% of the non-Finnish population residing in the country in 2011 (Statistikcentralen, Citation2012a). This can be compared to the situation in Sweden, where the proportion of foreign-born inhabitants is 15% (SCB, Citation2012). Thus, the focus of our study is on two countries with very different migration regimes (see also Papadopoulos, Citation2010).

In addition to the differences we have discussed between Sweden's and Finland's migration regimes, it seems also relevant to consider ethnic diversity within the framework of these two countries’ elderly care systems. Finland's quite recent history as a country of immigration is of course reflected in the fact that the proportion of older people with an immigrant background is relatively small. The situation will change, however, during the years to come. In 2011, 19% of the Finnish-, Swedish- or Sami-speaking Finns were older than 65 years (Statistikcentralen, Citation2012a). Among other language groups the corresponding figure was 3.2%. This can be compared to the situation in Sweden, where the proportion of foreign-born inhabitants over 65 at the end of 2011 was 11.7% (SCB, Citation2012). In the present context, it is also interesting to note that the ethnic diversity among staff in these two countries’ elderly care sectors has increased gradually over the years, though at different rates and to different extents. The latest report on elderly care published by the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions states that “among the total number employed in the area of elderly care and care for the disabled, the proportion of foreign-born individuals has increased during the past 10-year period, from 10 to 14% in 2008. It is primarily the proportion of staff born outside the Nordic region and the EU that has increased” (SKL, Citation2009; our translation). The situation in Finland is different. In 2009, the proportion of foreign-born practical nurses amounted to 4.5% of staff in Finland, while the proportion of foreign-born nurse assistants was 7% (Statistikscentralen, Citation2012b).Footnote1 There are, naturally, large regional differences. For instance, in Helsinki, the proportion of foreign-born elderly care staff increased from 8.6 to 10.1% between 2007 and 2008 (Statistikscentralen, Citation2012c). Thus, although the ethnic diversity among elderly care staff is not as great in Finland as it is in Sweden, there is considerably greater variation in staff members’ linguistic, ethnic, and cultural backgrounds today than there was two decades ago.

The focus of this study is therefore in line with Kilkey, Lutz, and Palenga-Möllenbeck (Citation2010) as well as Williams’ (Citation2010) suggestion that there is a need for research that can elucidate the relationship between care regimes and migration regimes. Researchers working in Nordic countries, too, have called for similar efforts and have stressed the fact that elderly care systems in these countries face the challenge of dealing with increased ethnic diversity among elderly care providers as well as elderly care recipients and their relatives (see, e.g. Forssell & Torres, Citation2012; Näre, Wrede, & Zechner, Citation2012; Nordberg, Citation2012; Torres, Citation2012, Citation2013). Given these developments, the overall aim of this study is to investigate media representations of elderly care in relation to ethnicity and migration issues in Sweden and Finland given that the two countries have common elderly care regimes but different migration regimes.

METHODS

The project as a whole has used both quantitative and qualitative content analysis. However, we have followed the recommendations of Silverman (Citation2001), in that we have tried to answer the “what” questions before beginning analyses focused on the “how” questions. Thus, all our analyses have begun with a quantitative approach to illustrate what the daily press reporting under study is about, before we continue with our qualitative content analysis to illustrate how the reporting deals with the themes that emerge as central in the quantitative analysis. In the present article, we will only present the results of the quantitative content analysis (cf. Hansen, Cottle, Negrine, & Newbold, Citation1998; Neuendorf, Citation2002). Thus, the aim of the present study is to answer “questions concerning the prevalence of various types of categories in a corpus of data. This may concern how often or frequently various categories occur or how much scope in terms of time or space various categories are allocated” (Esaiasson, Gilljam, Oscarsson, & Wängnerud, Citation2007: 223; our translation).

The empirical data on which our study is based were selected from one of the major daily newspapers in Sweden, Svenska Dagbladet (SvD), and from Helsingin Sanomat (HS), the largest national daily newspaper in Finland.Footnote2 The corpus contains articles that deal with elder care as well as issues of ethnicity, culture, language, religion and migration. The study covers the period 1995–2011. The primary reason for focusing on this period is that it was during the mid-1990s that the debate on elder care and ethnicity- and migration-related issues started in earnest in Sweden and Finland. The search words used for selecting the newspaper articles through Mediearkivet and Helsingin Sanomat's electronic archive were: elderly care, geriatric care, old person, elderly, immigrant, ethnic, ethnicity, culture, foreign, language, multicultural, diversity, labor immigrant, labor immigration and migration (in Swedish: äldrevård*, äldreomsorg*, åldring*, äldre*, invandrar*, etnis*, etnicitet*, kultur*, utlän*, språk*, mångkultur*, mångfald*, minoritet*, arbetsinvandrar*, arbetskraftsinvandrar* and migration* /// in Finnish: vanhu*, maahanm*, etni*, kulttuuri*, ulkoma*, kieli*, monikulttuuri*, moninaisuu*, vähemmistö*, työperäi*, siirtolai* and siirtotyö*). The * indicates that all words beginning with the root word in question have been searched. All of the daily newspaper articles published during the period in question which followed the sampling criteria have been analyzed (N=347 articles, 123 from SvD and 224 from HS).Footnote3

In order to systematize the analyses and create conditions for good reliability, a code book has been used (cf. Esaiasson et al. Citation2007). The code book describes the principles used when coding the data for this study (this is what Nilsson, Citation2000 calls a coding scheme). A code book or coding scheme also allows researchers to operationalize the variables used in a quantitative content analysis. Establishing coding principles has been particularly important because the newspaper articles under study seldom concern solely the relationship between elderly care and ethnicity- and migration-related issues, but also deal with many other topics. A given article might contain information that is not useful in the analyses in focus, and thus only part of the content is coded. To allow us to distinguish the meaning of various codes within and between articles, a main code was established for each article in relation to each of the questions we posed when analyzing the data. The main code was determined through quantitative measures. This means that the number of column millimeters for each code was calculated and compared before establishing the main code. The fact that working on the basis of a main code is something that could lead to certain topics seeming underrepresented is something we acknowledge. This problem is, however, innate to the way in which quantitative content analysis are performed since limits need to be set for how the data is coded. The data were analyzed according to quantitative content analysis methods using SPSS.

Coding of data for the entire project was based on a number of questions posed while going through the empirical corpus. These question dealt with genre (What type of article is it?), topics (What is discussed in connection with ethnicity- and migration-related issues in the area of elderly care?), elderly care actors (What care role does the article focus on: elderly care recipients, elderly care providers or relatives of recipients?), reasons for the account (How is bringing up a specific topic justified?), participants (What individuals are allowed to express themselves, or whose arguments are used?) and ethnic background (Does the elderly care actor who expressed him-/herself belong to the ethnic majority or an ethnic minority?). In this article, we focus on the issues that have proven to be most relevant to the study's research questions.

With regard to the coding, it should be noted that it has been based to some extent on the authors’ expertise in the areas discussed in the articles.Footnote4 This means that the codes dealing with genre were predefined according to the genre types typically used in media research, whereas the codes for elderly care actors were based on previous research on older people and aging. The codes for ethnic background were also based on common practice in the area of media research on ethnicity and migration. All of the above codes have been developed deductively. This is in contrast to the codes dealing with topics and reasons for the account which were developed inductively and can therefore be regarded as codes that were generated from the data. The coding was conducted through the following procedure: we have first carried out a close reading of the corpus, formed an understanding of it, coded it by country, discussed the coding for each country with one another and worked through those cases in which there have been doubts about how delimitations should be made. Finally, we have re-coded when necessary. This means that while coding the data, our research team had a continuous dialogue, the aim of which was to ensure that the data from both countries were treated in a similar manner. This means that we discussed our coding principles and code delimitations in line with what Creswell (Citation1998) calls peer-debriefing sessions. These discussions, along with constant consideration of alternative codes (cf. Silverman, Citation2001), were intended to increase the reliability of the analyses.

RESULTS

The newspaper corpus contains both news articles and debate articles (letters to the editor/editorials). Most of the articles we have analyzed contain news, and our results show certain genre-specific dividing lines between the two countries (63.8% of the Finnish articles and 72.4% of the Swedish articles contain news-matter). There are also other important differences between the Finnish and Swedish reporting in relation to topics, elder care actors, these actors’ ethnic background, and reasons for the account, which are the factors we will primarily focus on here. We will begin by presenting findings on the topics and changes in the space allocated to them over time.

Topics

Our analysis of the empirical data revealed five dominant topics, inductively emerging from the data: 1) culture-appropriate elderly care, 2) labor immigration, 3) organizational and working environment issues, 4) the recruitment of immigrants already residing in the country, and 5) care-seeking migration. Thus, it is in relation to these topics that the newspapers’ discussions of ethnicity- and migration-related issues in elderly care in Finland and Sweden must be understood. Table shows how the reporting is distributed.

Table I Topics and their distribution by country.

If we consider the Finnish and Swedish newspaper reporting as a whole, we see that the largest proportion of articles deal with “culture-appropriateness” (33.7% of the articles discuss this topic). This concerns, in various respects, the need to shape the Finnish or Swedish elderly care system so that it can meet the “special needs” that a multicultural aging population is assumed to have. This topic should be understood in a broad sense. It encompasses references to language, religion, manners and customs, and food as well as cultural values in general. The combined Finnish and Swedish newspaper reporting has shown less interest in questions of “labor immigration” (a topic found in 19.6% of the articles). This topic is different from what we have called the “recruitment of immigrants already residing in the country,” which is found in the reporting almost as often (16.4% of the articles). The topic of recruitment includes articles on efforts to employ immigrants who already live in Finland or Sweden (e.g. unemployed immigrants or immigrants working in other areas), while labor immigration refers to “importing” care workers to Finland or Sweden. Another well-represented topic is elderly care as a workplace, which includes aspects related to working conditions and organizational issues (this topic is found in 17.6% of the articles).Footnote5 Finally, we have the topic “care-seeking migration” (found in 12.7% of the articles). This topic concerns individuals who reside in another country and who travel to Finland or Sweden to pay for use of the elderly care offered there, or older persons who travel from Finland or Sweden to other countries to purchase care services. As we see in Table , there is a great difference between the two countries here: While this topic is seldom represented in the Swedish corpus (3.3%), it is found much more often in the Finnish corpus (17.9%).

Another notable difference between the two countries’ foci, which we will return to, is that the most common topics in the Finnish context are labor immigration (25.9%) and, running a close second, culture-appropriate care (25.4%). In contrast, the Swedish reporting is clearly dominated by the issue of culture appropriateness, with almost half of the studied articles having this focus (48.7%). After this topic comes the recruitment of migrants to the sector (29.3%), the importance of which matches that given to labor immigration issues in the Finnish corpus. The findings show that the share of articles on labor immigration and recruitment are inversely proportional in the two countries (in Sweden, 29.3% of the articles concern recruitment and 8.1% labor immigration, while in Finland the corresponding figures are 9.4 and 25.9%). Another marked difference is that the Finnish press has focused much more on issues related to the elderly care sector as a workplace than has the Swedish press (21.4 and 10.6% of the articles, respectively). Some of these articles, however, have been general discussions of how elderly care is to be organized in the future, particularly how staff shortages can be dealt with. As noted above, the Swedish and Finnish migration regimes are quite different in terms of the history and scope of migration. This is reflected in the daily press reporting, where it is possible to observe what the ethno-cultural landscape looks like among recipients and what type of migration has been predominantly discussed in relation to the sector.

Changes in topics over time

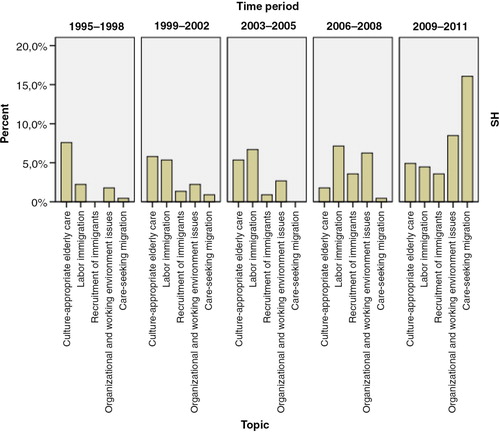

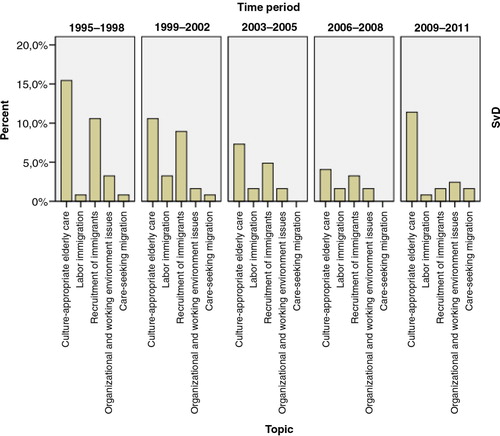

In connection with the description of the topics dealt with, and in line with the social constructivist approach utilized in this study, it is also interesting to analyze the extent to which the focus of the reporting has changed during the period under study (1995–2011). The bar diagrams below (i.e. and ) show HS's and SvD's reporting of various topics over time. Every bar indicates the proportion of articles on a given topic of the entire number of articles in the Finnish and Swedish newspaper data, respectively.

shows that in the Finnish daily press reporting (i.e. in HS) from the mid-1990s to a few years into the new century, the main topic was issues of culture-appropriateness. This topic was particularly predominant during the period 1995–1998. These articles in large part concerned the right of Finnish-speaking individuals living in Sweden to elder care in Finnish and the right of Swedish-speaking Finns to receive care in Swedish in Finland. A few years into the 2000s, the main focus shifted to labor immigration issues, which also characterized Finnish newspaper reporting as a whole and reflected the policy attention to these issues during that time. Also of interest is the sharp recent increase in issues surrounding care-seeking migration, a topic that was clearly predominant in the Finnish reporting during the period 2008–2011. These articles primarily concern a few cases, which received a great deal of attention, concerning immigrants residing in Finland whose ailing, older parents had been threatened with deportation. Finally, during this period we find an increased interest in workplace-related issues, a topic that previously received more limited attention. This focus is partly tied to the recruitment of new staff to the Finnish elderly care sector.

In contrast to the Finnish reporting, we see in that the focus in the Swedish context has been on culture-appropriate care. Although the topic of recruitment of immigrants to the sector has also been important, in the time period under study articles on culture-appropriate care have predominated. Moreover, as noted above, we see a clear difference between the Finnish and Swedish treatment of recruitment versus labor immigration issues. A temporal comparison also reveals that this difference was greatest during the period 1995–1998. In Finland, the issue of recruiting staff was not discussed at all at the beginning of the study period.

Actors within elderly care

Another significant aspect of the daily press reporting concerns which elderly care actors the newspapers have focused on. In other words, have the Finnish and Swedish daily newspapers primarily covered elderly care recipients, elderly care providersFootnote6 or recipients’ relatives?Footnote7 In this context, it is also interesting to look at how the newspaper coverage is distributed with respect to the ethnic majority in the two countries (i.e. Finns and Swedes) and ethnic “Others” (immigrants and national ethnic minorities) as elderly care recipients, elderly care providers or recipients’ relatives. Table shows how the topics in the daily press reporting are related to the elderly care actors and their ethnic background. Note here that certain topics are only found in isolated articles; this must be kept in mind when considering the percentages reported in Table and III . Thus, these tables also provide the number of articles for each topic and country.

Table II Topics in relation to elderly care actors and their ethnic background.

Table III Topics in relation to reasons for the account, by country.

The results for the Finnish and Swedish data taken together which are shown in Table show that the reporting allocated almost the same amount of space to ethnic “Others” as elderly care providers (48.87% in the Finnish and 45.5% in the Swedish data) and as elderly care recipients (46.2% in the Finnish and 48.8% in the Swedish data). On the other hand, the newspapers’ coverage of the perspective of relatives has been marginal, as has that of the role of the majority population as care providers or recipients (as seen in the table, these categories are only found in a few percent of the articles). The analysis also reveals that when the need for culture-appropriate care is discussed, this occurs almost exclusively in relation to care recipients with an immigrant background, in both the Finnish and Swedish data (see Lindblom & Torres, Citation2011, who discuss possible mechanisms underlying this finding in relation to the Swedish context). Similarly, we also find that issues of labor immigration and the recruitment of immigrants already residing in the country are almost exclusively dealt with in relation to the role of elderly care providers. And here too, this applies to the vast majority of articles in both countries.

One of the more pronounced differences between the Finnish and Swedish reporting is the coverage of workplace issues, which, as mentioned, is more frequent in HS than in SvD. In relation to this difference we can add that, in the Finnish context, the focus has been on the situation of both care providers (40.4%) and care recipients (44.7%) when workplace issues have been brought up. In the Swedish corpus, however, there has been a clear focus on care providers in the reporting on this topic (76.9% of the articles).

Reasons for the account

As we have shown, there is a clear connection between the topics discussed in the daily press and the elderly care actors in focus, in both the Finnish and the Swedish newspaper reporting. In this light, it seems interesting to elucidate the reasons for the accounts that are stated in relation to the various topics covered in both countries. By “reasons for the account” we mean the justifications given for reporting on a specific topic. Table shows the results of this analysis, where we have divided these reasons into four types: culture-, economy-, organization-, and demography-related justifications.Footnote8 The culture-related reasons include those based on discussions of culture, language and religion. The other types of reasons are related to economic, organizational and demographic conditions. The remaining stated reasons for bringing up a given topic have been categorized as “Other.” Here we find, among other reasons, the few discrimination- and exploitation-related ones.

These results support the conclusion that different topics are dealt with according to different logics. As seen in Table , there is a clear tendency in both the Finnish and Swedish newspaper reporting to use culture-related justifications when culture-appropriateness is discussed, while economy-, organization- and demography-related justifications tend to be used when labor immigration and the recruitment of immigrants already residing in the country are under discussion. If we then look at a more detailed level (not shown in the table), we find that it is primarily reasoning based on language—i.e. aspects concerning the need for one's native language, bilingualism, struggles for language recognition (regarding national minorities), communication problems—that are used to justify the topic “culture-appropriate care.” However, the predominance of language issues is greater in the Finnish daily newspaper (71.9% of the reasons for bringing up culture-appropriate care in the Finnish data concern aspects of language, while the corresponding figure for the Swedish data is 51.7%). This imbalance can be explained by the fact that a large proportion of the articles on culture-appropriate care in the Finnish context deal with the right of Finns living in Sweden to receive elderly care in Finnish and to the right of Swedish-speaking Finns to receive care in the Swedish language.

The reasons for taking up the topic of labor immigration adhere to a different pattern. In this case, in both HS and SvD, it is the economic, organizational and demographic reasons that predominate (90% of articles in SvD and 81% in HS state this reason). In a typical case, this means that the topic of labor immigration has been related to the anticipated shortage of staff within elder care, to the belief that the proportion of older people is growing and will continue to grow, or to issues concerning the various economic costs of caring for older people. Looking at the Finnish corpus, we find that labor immigration has also been discussed from the perspective of exploitation and discrimination (6.9% of the articles on this topic are characterized by these issues; see column titled “Other” in Table ), whereas such reasoning is absent from the Swedish corpus. Reasoning based on the economy, organization and demography also predominates in the topic of recruiting to the sector immigrants already living in the country (57.1% of articles in HS and 66.7% in SvD have this focus). Finally, we also find that the topic of care-seeking migration is justified using the same logic (77.5% of the articles in the Finnish data and 100% in the Swedish data state reasons based on the economy, organization and demography).

DISCUSSION

In this article, we have focused on media representations of ethnicity- and migration-related issues within the framework of elderly care in two Nordic countries with similar care regimes and dissimilar migration regimes: Sweden and Finland. The quantitative content analysis presented here is based on a comparison of daily press reporting in two daily newspapers (SvD and HS) between 1995 and 2011. The analysis reveals both similarities and differences. First of all, the daily press reporting in these two countries has focused on virtually the same topics. Looking at the combined coverage in the two countries, we see that the topic brought up most frequently is the need for culture-appropriate care which could be understood against the backdrop mentioned in the introduction as far as the increased ethno-cultural diversity among elderly care recipients that has been brought to the fore by the globalization of international migration. The topic of culture-appropriate care is closely followed by issues concerning labor immigration, elderly care as a workplace and recruiting of immigrants already living in the country to the sector. All of these topics are also topics that the debate on globalization's impact on elderly care has brought attention to. This means that the daily newspaper articles analyzed here have brought these issues to the public's attention just as the academic debate on globalization has increased the awareness of elderly care planners and providers across Europe as far as the challenges in question are concerned.

Country-dependent differences are also seen, however. Whereas the Swedish daily press has mainly focused on the need for culture-appropriate care and the recruitment of settled immigrants to the sector, the Finnish articles have stressed labor immigration (i.e. importing foreign labor to the sector) and culture-appropriateness. This difference can be explained in part with reference to the two countries’ different migration regimes. As implied in the section on these countries’ migration regimes, Sweden has pursued active immigration policies for several decades, resulting in a population characterized by relatively great ethnic and cultural diversity. In this context, it is also interesting to note that this is probably the reason why Swedish research on health and social care has long debated the issue of culture-appropriateness (see, e.g. Ronström, Citation1996; Torres, Citation2006, Citation2008, who have discussed this specifically in relation to elderly care). In Finland, on the other hand—which has a different migration regime and where the working and older populations are not as ethnically and culturally differentiated as in Sweden—it is not surprising that the daily press reporting has primarily dealt with labor immigration. The fact that the Finnish press has nevertheless stressed the need for culture-appropriate care depends on its considerable coverage of the language rights of Finns with a Swedish background. Worth noting is perhaps that the Finnish press has also actively reported on the linguistic rights of native Finnish-speakers in Sweden. We note, however, that the cultural and linguistic rights of the indigenous Sami population in both countries have only received random attention.

Our analysis of trends in the two countries’ daily press reporting during the period 1995–2011 shows that the Swedish newspaper has primarily reported on issues concerning culture-appropriateness. This applies to all of the 3- and 4-year periods under comparison, although interest in the topic has diminished somewhat over time. Culture-appropriateness is also the most common topic in the Finnish data, particularly during the period 1995–1998. However, issues related to this topic began having less influence in the mid-2000s, probably due to the entrance of labor immigration into the public debate. The mid-2000s also marks the increased visibility of issues concerning organizational and working environment issues in the Finnish reporting. This is related to the very beginning of a discussion of the problem of how elderly care can be organized in a time of demographic change, where one important solution is thought to be labor immigration as stated in the introduction. However, few articles deal specifically with the challenges associated with a multicultural workplace. Many articles are, instead, portraits of individuals with a foreign background who work within the elderly care sector, but they also include discussions on salary conditions and, to a lesser degree, on how care of older immigrants should be organized. Finally, we see that issues of care-seeking migration have had a great impact in the Finnish reporting during the period 2008–2011, when this topic is clearly predominant. This is primarily due to the public attention given to cases of ailing “grandmothers” who have been threatened with deportation, despite the fact that they are completely dependent on the care provided by their adult children, who are immigrants living in Finland. Our analysis of the Swedish data also shows that interest in issues concerning the recruitment of immigrants already living in the country to the sector has diminished somewhat over the years. The fact that the Swedish daily press reporting under study has not dealt with the challenges inherent in cross-cultural encounters would seem interesting, particularly in light of the relatively great ethnic and cultural diversity in Sweden—compared to the situation in Finland—as well as the large proportion of individuals with an immigrant background working in the Swedish elderly care sector. Based on these findings, we conclude that the mediated construction of a culturally and ethnically heterogeneous elderly care landscape does not recognize the complexity of challenges that this diversity poses to the elderly care sector. Worth noting is perhaps that similar conclusions have been drawn by Torres (Citation2012) who has studied the way in which the Swedish debate within the sector itself has been carried out.

Our analysis of the Finnish and Swedish text corpus as a whole shows that elderly care providers who are ethnic “Others” have received the most attention, followed closely by elderly care recipients with a non-majority ethnic background. On the other hand, the viewpoints and reflections of relatives of care recipients are almost non-existent. Similarly, we have shown that the perspective of the ethnic majority (Swedes and Finns) has received little coverage. Thus, it seems that the ways in which increased diversity in elderly care is constructed in Swedish and Finnish daily newspaper articles on elderly care is as a concern for minority groups, and as something that the majority need not bother about. In other words, issues related to ethnicity and migration are regarded—contrary to how the debate on globalization's impact on elderly care mentioned alluded to in the introduction addresses them—as issues that can be relegated to the periphery of the elderly care landscape. Thus, the daily press debate on these issues has been carried out as if the challenges at stake are challenges that primarily concern the “Other” as opposed to being challenges for the sector as a whole. In summary, the present analysis provides good insights into how the public debate on ethnicity- and migration-related issues concerning elderly care have developed during a period in which the issue of diversity has become more pronounced in both Finland and Sweden. Given that this debate has been pursued as if it only concerned a small fraction of actors in the elderly care sector, it is clear that the public debates in these countries show little or no understanding of how globalization, international migration and increased ethnic diversity can affect the elderly care sector on a more fundamental level (cf. Torres, Citation2012).

Acknowledgements

The study presented here is part of a project comparing Finnish and Swedish daily press reporting on elderly care. The project is led by the first author in Sweden and by the third author in Finland. The first author's work with the study had been funded in part by a grant from FLARE (Future Leader of Aging Research in Europe), which ran from 2008 to 2011 (reg. no. 2007-1727). The second author's work with the study has been funded in part by a research program entitled Åldrande och omsorgens former: Tid, plats och äldreomsorgsaktörer (Aging and Forms of Care: Time, Place and Actors in Elderly Care) financed by the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research (project # 2006-1621 & 2007-1954), and led by Prof. Eva Jeppsson-Grassman at Linköping University. The third author's involvement in this study has been funded by the Finnish Academy through a project entitled The Shaping of Occupational Subjectivities of Migrant Care Workers: A Multi-Sited Analysis of Glocalising Elder Care (2011–2015, Decision no. 251239). A Swedish version of this paper covering the period between 1995 and 2008 can be found in Torres, Lindblom, and Nordberg (Citation2012).

Notes

1. Practical nurses are found within elderly care and other health and medical care sectors, but it is the predominant occupational category among elderly care staff in Finland.

2. The choice to study Svenska Dagbladet (SvD) is based on the fact that this paper is one of the largest national newspapers in Sweden and that it is indexed in the most user-friendly database for news excerpts that we have in Sweden; Mediearkivet. This database includes articles published in SvD starting in 1995, which is not the case for the other national Swedish newspaper, Dagens Nyheter. The choice of a Finnish daily newspaper was a given, as there is only one major, national paper in Finnish in Finland.

3. Our first database search resulted in about 1,300 articles in the Swedish corpus and 1,600 in the Finnish corpus. We soon established, however, that most of the articles dealt with either ethnicity or elderly care, not both, and selecting articles containing both was our main criterion. A few articles were doubles. Articles on theatrical productions, obituary notices and the like were outside the study aim and thus excluded. The fact that the Finnish sample is larger is perhaps surprising. Differences in the ways in which the database engines utilize work may explain why this is the case. We do not know, however, for a fact if this is the case and abstain therefore from giving an explanation for the differences in the number of articles that have addressed the issues in focus in the two daily presses in question.

4. The first author works in the area of older people and aging, while the second and third authors have experience with media analysis. Both the first and third authors have also conducted research on issues concerning international migration and ethnic relations.

5. We have also coded the debate on poor salary conditions for nurse assistants in this category, as well as general discussions on how elderly care should be organized in the future. Moreover, the topic includes articles on using lessons learned in other countries to deal with problems within the Finnish and Swedish elderly care systems.

6. The code “care provider” typically includes all staff employed in elderly care, but here we have expanded it to include people running companies that offer care services for older people.

7. The code “relative” includes friends, close family, relatives or other individuals who have some kind of relationship with the person receiving elderly care.

8. Here, too, it is important to remember that the percentages must be considered in light of the number of articles per topic, which is why we also provide the frequency of articles in parentheses in this table.

References

- Anttonen A., Sipilä J. European social care services: Is it possible to identify models?. Journal of European Social Policy. 1996; 6(2): 87–100.

- Atuel H., Seyranian V., Crano W.D. Media representations of majority and minority groups. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2007; 37: 561–572.

- Barker C. Cultural studies: Theory and practice. 2000; London: Sage.

- Bettio F., Plantenga J. Comparing care regimes in Europe. Feminist Economics. 2004; 10: 85–113.

- Bettio F., Simonazzi A., Villa P. Change in care regimes and female migration: The ‘care drain’ in the Mediterranean. Journal of European Social Policy. 2006; 16: 271–285.

- Bredström A. de los Reyes P., Molina I., Mulinari D. Maskulinitet och kamp om nationella arenor: reflektioner kring bilden av “invandrarkillar” i svensk media [Masculinity and struggles on national arenas: reflections about the image of ‘immigrant boys’ in Swedish media]. 2002; Stockholm: Atlas. 182–206. Maktens (o)lika förklädnader: kön, klass och etnicitet i det postkoloniala Sverige [The different disguises of power: Sex, class and ethnicity in postcolonial Sweden].

- Bredström A. Gendered racism and the production of cultural difference: Media representations and identity work among “immigrant youth” in contemporary Sweden. NORA. 2003; 2(11): 78–88.

- Brune Y. de los Reyes P., Molina I., Mulinari D. Invandrare i mediearkivets typgalleri [Immigrants in the typical media gallery]. Maktens (o)lika förklädnader: kön, klass och etnicitet i det postkoloniala Sverige [The different disguises of power: Sex, class and ethnicity in postcolonial Sweden]. 2002; Stockholm: Atlas. 150–181.

- Brune Y. Nyheter från gränsen: tre studier i journalistik om invandrare, flyktingar och rasistisk vård [News from the edge: Three studies on journalism about immigrants, refugees and racist violence]. 2004; Göteborg: JMG.

- Brune Y. Camauer L., Norhstedt S.A. Den dagliga dosen: diskriminering i nyheterna och bladet [The daily dosage: Discrimination in the news]. Mediernas vi och dom: mediernas betydelse för den strukturella diskrimineringen. [The media's ‘Us’ and ‘Them’: The importance of the Media for Structural Discrimination]. 2006; Stockholm: Statens Offentliga Utredningar (SOU 2006:21). 89–122.

- Brune Y. Darvishpour M., Westin C. Bilden av invandrare i svenska nyhetsmedier [The image of immigrants in Swedish news media]. Migration och etnicitet: perspektiv på ett mångkulturellt Sverige [Migration and ethnicity: Perspectives on multicultural Sweden]. 2008; Lund: Studentlitteratur. 335–361.

- Burr, V. (1995). An introduction to social constructionism. London: Routledge. [PubMed CentralFull Text].

- Caldas-Coulthard C. Weiss G., Wodak R. Cross-cultural representation of ‘otherness’ in media discourse. Critical discourse analysis: Theory and interdisciplinarity. 2003; New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. 272–296.

- Cisneros J.D. Contaminated communities: The metaphor of ‘immigrant as pollutant’ in media representations of immigration. Rhetoric & Public Affairs. 2008; 11(4): 569–602.

- Creswell J.W. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. 1998; London: Sage.

- Dahlsted M. Sverige har fått getton: medierepresentationer av den hotfulla ‘invandrarförorten’ [Sweden has now a ghetto: Media representations of the threatening ‘immigrant suburb’]. Nordisk samhällsgeografisk tidskrift [Nordic Journal of Social Geography]. 2004; 36: 3–26.

- Elsrud T., Lalander P. Projekt Norrliden: om småstadspressens etnifiering och genderisering av en förort [Project Norrliden: On a small town's ethnification and the gendering of a suburb]. Sociologisk forskning [Sociological Research]. 2007; 2: 6–25.

- Esaiasson P., Gilljam M., Oscarsson H., Wängnerud L. Metodpraktikan: konsten att studera samhälle, individ och marknad [Methods practice: The art of studying society, individuals and markets]. 2007; Stockholm: Norstedts förlag.

- Esping-Andersen G. The three worlds of welfare capitalism. 1990; Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Ferguson R. Representing ‘race’; ideology, identity and the media. 1998; New York: Arnold.

- Forssell E., Torres S. Social work, older people and migration: An overview of the situation in Sweden. European Journal of Social Work. 2012; 15(1): 115–130.

- Forssell E., Torres S., Olaison A. Care managers’ experiences of cross-cultural need assessment meetings: The case of late-in-life immigrants. Ageing & Society. 2013. [PubMed Abstract] [PubMed CentralFull Text].

- Gardikiotis A., Martin R., Hewstone M. The representation of majorities and minorities in the British press: A content analytic approach. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2004; 34: 637–646.

- Gergen K. Social constructionism. 1995; London: Sage.

- Grzymala-Kazlowska A. Clashes of discourse: The representations of immigrants in Poland. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies. 2009; 7: 58–81.

- Haavisto C. Conditionally one of ‘us’ A study of print media, minorities and positioning practices. 2011; Helsinki: Swedish School of Social Science, University of Helsinki.

- Hall S. Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices. 1997; London: Sage.

- Hansen A., Cottle S., Negrine R., Newbold C. Mass communication research methods. 1998; London: Macmillan.

- Hartmann P., Husband C. Racism and the massmedia. 1974; London: Davis-Poynter.

- Helander M. Totta toinen puoli? Työperäisen maahanmuuton todelliset ja kuvitellut kipupisteet [Partly true? The real and imagined problems of labour immigration]. 2011; Helsingfors: Svenska social- och kommunalhögskolan. SSKH skrifter nr. 31.

- Horsti K. Hope and despair: Representations of Europe and Africa in Finnish news coverage of “migration crisis.”. Estudos em Comunicação, 3. 2008. Retrieved from: http://www.ec.ubi.pt/ec/03..

- Kilkey M., Lutz H., Palenga-Möllenbeck E. Introduction: Domestic and care work at the intersection of welfare, gender and migration regimes: Some European experiences. Social Policy & Society. 2010; 9(3): 379–384.

- King R., Wood N. Media and migration: Constructions of mobility and difference. 2001; London: Routledge.

- Kofman E. Rethinking care through social reproduction: Articulating circuits of migration. Social Politics. 2012; 19(1): 142–62.

- Koslowski R. European migration regimes: emerging, enlarging and deteriorating. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 1998; 24(4): 735–749.

- Lindblom J., Torres S. Etnicitets- och migrationsrelaterade frågor inom äldreomsorgen: en analys av SvD:s rapportering mellan 1995–2008 [Ethnicity and migration-related issues within elderly care: an analysis of SvD's reporting between 1995–2008]. Socialvetenskaplig Forskning. 2011; 18(3): 222–243.

- Littlefield M.B. The media as a system of racialization: Exploring images of African American women and new racism. American Behavioral Scientist. 2008; 51(5): 675–685.

- Lutz H. Migration and domestic work: A European perspective on a global theme. 2008; Hampshire, UK: Ashgate.

- Miller J.J. Immigration, the press and the new racism. Media Studies Journal. 1994; 8: 19–28.

- Misra J., Woodring J., Merz S. The globalization of care work: Neoliberal economic restructuring and migration policy. Globalizations. 2006; 3(3): 317–332.

- Neuendorf K. The content analysis guidebook. 2002; Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Nilsson Å. Ekström M., Larsson L. Kvantitativ innehållsanalys [Qualitative content analysis]. Metoder i kommunikationsvetenskap [Methods in communication science]. 2000; Lund: Studentlitteratur. 111–139.

- Nordberg C. Beyond representation: Newspapers and citizenship participation in the case of a minority ethnic group. Nordicom Review. 2006; 27(2): 87–104.

- Nordberg C. Boundaries of citizenship: The case of the Roma and the Finnish nation-state (Doctoral Dissertation). 2007. SSKH Skrifter 23, Swedish School of Social Science, Helsinki.

- Nordberg C, Boucher G., Grindsted A. Localising global care work: A discourse on migrant care workers in the Nordic Welfare Regime. Transnationalism in the Global City. 2012; Bilbao: University of Deusto. 63–78.

- Näre L., Wrede S., Zechner M. Työn glokalisaatio [Glocalisation of work]. Sosiologia. 2012; 49(3): 185–189.

- Papadopoulos T. Carmel E., Cerami A., Papadopoulos T. Immigration and the variety of migrant integration regimes in the European Union. Migration and welfare in the New Europe: Social protection and the challenges of integration. 2010; Bristol: Policy Press. 23–47.

- Pfau-Eiffinger B. Welfare state policies and the development of care arrangements. European Societies. 2005; 7(2): 321–347.

- Pred A. Even in Sweden: Racisms, racialized spaces and the popular geographical imagination. 2000; Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Ronström O. Vem ska ta hand om de gamla invandrarna? [Who is going to care for elderly immigrants]. 1996; Stockholm: Socialtjänsts Forsknings- och utvecklingsbyrå FoU-rapport 1996: 3.

- Sarbin T.R., Kitsuse J.I. Constructing the social. 1994; London: Sage.

- SCB (Statistiska central byrån). Befolkningsstatistik [Population statistics]. 2012. Retrieved from http://www.scb.se..

- Silverman D. Interpreting qualitative data: Methods for analysing talk, text and interaction. 2001; 2nd ed, London: Sage.

- SKL (Sveriges Kommuner och Landsting). Aktuellt på Äldreområdet 2008 [News on the elderly care area 2008]. 2009. Retrieved from http://www.skl.se/vi_arbetar_med/socialomsorgochstod/publikationer/aktuellt_pa_aldreomradet_2008..

- Statistikcentralen. Befolkningsstruktur [Population structure]. 2012a. Retrieved from http://pxweb2.stat.fi/database/StatFin/vrm/vaerak/vaerak_sv.asp..

- Statistikcentralen. Yrke och födelseland [Occupation and country of birth]. 2012b. Statistik erhållen av Airi Pajunen, Statistikcentralen, mars 2012 [Statistics retrieved in March 2012 by Airi Pajunen from the central statistics bureau in Finland].

- Statistikcentralen. Arbetsområde och födelseland – Helsingfors [Work area and country of birth—Helsingfors]. 2012c. Statistik erhållen av Airi Pajunen, Statistikcentralen, maj 2012 [Statistics retrieved in March 2012 by Airi Pajunen from the central statistics bureau in Finland]..

- Stewart C.O., Pitts M.J., Osborne H. Mediated intergroup conflict: The discursive construction of ‘illegal immigrants’ in a regional U.S. newspaper. Journal of Language and Social Psychology. 2011; 30(1): 8–27.

- Szebehely M. Äldreomsorgsforskning i Norden: en kunskapsöversikt [Elderly care research in the Nordic region: An inventory of knowledge]. 2005; Copenhagen, Denmark: Nordiska Ministerrådet.. TemaNord, 508.

- Torres S. Elderly immigrants in Sweden: ‘Otherness’ under construction. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 2006; 32(8): 1341–1358.

- Torres S. Darvishpour M., Westin C. Äldre invandrare i Sverige: om homogeniserandet av en heterogen social kategori och skapandet av ett välfärdsproblem [Elderly immigrants in Sweden: On the homogenization of a heterogenous social category and the creation of a welfare problem]. Migration och etnicitet: perspektiv på ett mångkulturellt Sverige [Migration and ethnicity perspectives on multicultural Sweden]. 2008; Lund: Studentlitteratur. 393–410.

- Torres S. Jeppsson-Grassman E., Whitaker A. Globalisering av internationella migrationsflöden: nya utmaningar för den offentliga äldreomsorgen [The globalization of international migration flows: new challenges for public elderly care]. Åldrande och omsorgens gestaltningar: mot nya perspektiv [Aging and care: Toward new perspectives]. 2012; Lund: Studentlitteratur. 77–98.

- Torres S. Phellas C. Transnationalism and the study of aging and old age. Aging in European societies. 2013; New York, NY: Springer. 267–281.

- Torres S., Lawrence S. Old age and migration: An introduction to ‘the age of migration’ and its consequences for the field of gerontological social work. European Journal of Social Work. 2012; 15(1): 1–7.

- Torres S., Lindblom J., Nordberg C. Medierepresentationer av etnicitet och migrationsrelaterade frågor inom äldreomsorgen i Sverige och Finland [Media representations of ethnicity and migration-related issues in elderly care in Sweden and Finland]. Sociologisk Forskning. 2012; 49(4): 283–304.

- van Dijk T.A. Communicating racism: Ethnic prejudice in thought and talk. 1987; Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- van Dijk T.A. Elite discourse and racism. 1993; Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- van Sterkenburg J., Knoppers A., de Leeuw S. Race, ethnicity and content analysis of the sports media: A critical reflection. Media, Culture and Society. 2010; 32(5): 819–839.

- Warnes A.M., Friedrich K., Kellaher L., Torres S. The diversity and welfare of older migrants in Europe. Ageing and society. 2004; 24(3): 307–326.

- Williams F. Intersecting issues of gender, ‘race’ and migration in the changing care regimes of UK, Sweden and Spain. Paper presented to the Annual Conference of the International Sociological Conference Research Committee 19, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL 2005, September 8–10.

- Williams F. Migration and care: Themes, concepts and challenges. Social Policy & Society. 2010; 9(3): 385–396.

- Williams F., Gavanas A. Lutz H. The intersection of childcare regimes and migration regimes: A three-country study. Migration and domestic work: A European perspective on a global theme. 2008; Burlington, USA: Ashgate. 13–28.

- Wrede S., Näre L. Glocalising care in the Nordic Countries. Nordic Journal of Migration Research. 2013; 3(2): 57–62.

- Wrede S., Nordberg C. Vieraita työssä. Työelämän etnistyvä eriarvoisuus [Strangers in work: The ethnifying inequality in working life]. 2010; Helsinki: Palmenia.