Abstract

Small enterprises are often highlighted by politicians as important engines of economic growth and job creation. However, previous research suggests that self-employment might not be equally beneficial for individuals in terms of their income compared to regular employment. Several studies have in fact found that the self-employed may face a substantially higher poverty risk than do regular employees. The aim of the present study is to investigate to what extent income poverty is a good predictor of actual living standards among the self-employed. Is the relationship between income poverty and living standards different for self-employed compared to the regularly employed? To investigate this question we use a unique Swedish survey dataset including regularly employed (n=2,642) as well as self-employed (over-sampled, n=2,483). Income poverty is defined as living in a household with less than 60% of the median household income. Living standards are measured with a deprivation index based on 29 consumption indicators. The results show that even though income poverty is more prevalent among the self-employed than among the regularly employed, no evidence can be found suggesting that the self-employed have a lower standard of living than the regularly employed. Furthermore, when specifically comparing income poor self-employed with income poor regularly employed, we find that the income poor self-employed score significantly lower on the deprivation index even after the compositional characteristics of both groups are taken into account. The conclusion is that poverty measures based on income data underestimate the actual living standard of the self-employed.

Since the 1970s, small enterprises have been emphasized by politicians, scholars, and commentators as important engines of growth and job creation (Davidsson, Citation2005; Henrekson & Stenkula, Citation2009; Rainnie, Citation1989). The self-employed have been described as the new “heroes” of the global economy, and in a recent report published by the European Commission it was claimed: “improving the access to finance of small and medium-sized enterprises is crucial in fostering entrepreneurship, competition, innovation and growth in Europe” (European Commission, Citation2005, p. 2).

However, there may be a dark side to this rosy picture. Scholars have recently discussed the increased number of self-employed not only in terms of economic “heroes” but also in connection with a general increase in precarious employment (Andersson & Wadensjö, Citation2004b; Fudge, Citation2006; Kalleberg, Citation2011; Kautonen et al., Citation2010; Koch & Fritz, Citation2013; Vosko, Citation2006). Several studies have indeed found that the self-employed may face a substantially higher poverty risk than do employees (Bardone & Guio, Citation2005; Halleröd & Larsson, Citation2008b; Peña-Casas & Latta, Citation2004). One report even showed that the self-employed in Sweden had a higher poverty rate than did the unemployed (Peña-Casas & Latta, Citation2004). Other studies have found that the self-employed generally have lower income than do employed, and that individuals who transition from regular employment to self-employment often experience a sustained loss of income (Blanchflower & Shadforth, Citation2007; Hamilton, Citation2000). The implementation of reforms to increase the number of self-employed in society may therefore exact a cost paid by the individuals who become self-employed.

On the other hand, the reliability of the high poverty rate attributed to the self-employed has been questioned (Bardone & Guio, Citation2005; Bradbury, Citation1997; Carter, Citation2011). Several problems have been pinpointed. For example, studies have shown that self-employed may not report their whole earnings to administrative authorities (Alalehto & Larsson, Citation2012). Therefore, reported income may not accurately correspond to the total material resources self-employed can access, and consequently, the income measures commonly used in poverty research may not mirror the actual living conditions among the self-employed. However, most studies that have found high poverty rates among the self-employed have not explicitly focused on self-employed but instead on in-work poverty in general (e.g. Bardone & Guio, Citation2005; Halleröd & Larsson, Citation2008b; Peña-Casas & Latta, Citation2004).

It is furthermore hard to reliably investigate the situation of the self-employed since the most commonly used datasets (such as EU-SILC, European Community Household Panel, and various national datasets) are nationally representative, and since the self-employed constitute a rather small proportion of the population in many countries (e.g. in Sweden about 7%), the small n-numbers might yield unreliable results.

The aim of the present paper is to investigate to what extent income poverty is linked to actual living standards among self-employed in Sweden, and whether this relationship is different for self-employed compared to the regularly employed. Specifically, the study investigates whether the living standards differ between income poor self-employed and income poor regularly employed. To reach this aim, a unique Swedish survey dataset is used including regularly employed (n=2,642) as well as self-employed (over-sampled, n=2,483). With this dataset, it is possible to reliably estimate the income poverty rate among the self-employed as well as test whether there are differences between self-employed and regularly employed regarding the relationship between income poverty and actual living standards after taking compositional differences into account.

INCOME POVERTY AND LIVING STANDARD AMONG THE SELF-EMPLOYED

There are several studies showing that the income poverty rate among the self-employed is high. For example, Peña-Casas and Latta (Citation2004) found that the poverty rate was higher among self-employed than regularly employed in all EU-15 countries. On average, 6% of the employed were poor, while as many as 14% of the self-employed were poor. The poverty rate among the self-employed was highest in Portugal (28%), Austria (26%), and Sweden (24%). There are also several studies that have investigated the income situation of the self-employed (Andersson & Wadensjö, Citation2006; Blanchflower & Shadforth, Citation2007; Hamilton, Citation2000). Most of these studies have found that a greater proportion of the self-employed have low earnings compared with employed (however, a larger proportion of the self-employed also have higher earnings) (Hamilton, Citation2000; Shane, Citation2008; Weir, Citation2003). Furthermore, the transformation into self-employment from regular employment is also often followed by a decrease in income (Hamilton, Citation2000; Shane, Citation2008).

On the other hand, several researchers are skeptical to whether these findings on income poverty among the self-employed are reliable (Halleröd & Larsson, Citation2008b; Peña-Casas & Latta, Citation2004). For example, Bardone and Guio (Citation2005, p. 3) have claimed that “the reliability of income data for the self-employed is not guaranteed, given the potential problem of under-reporting of income.”

There are only a few studies that have explicitly studied poverty among self-employed in the OECD countries (Bradbury, Citation1997; Maloney, Citation2003), and we have only found one study that have investigated the actual living standard among the income poor self-employed (Bradbury, Citation1997). In this study, the overlap between income poverty and deprivation was investigated. Bradbury found that the self-employed with low income generally have higher living standard than do regularly employed with low income. He concluded that average income data represent a poor indicator of actual living standard among the self-employed.

There are several reasons why self-employed who are income poor might not have a low living standard. Carter (Citation2011), for example, argues that income might be a problematic measure of poverty, especially for the self-employed, since the self-employed often have irregular incomes. They might receive a larger share of their income in a single month or year, while often having quite low average income on a monthly or yearly basis. Taking this into account, Carter found that the self-employed actually were wealthier than the regularly employed, which might indicate that income data could be unreliable for the self-employed—especially when using cross-sectional data.

Another reason why income poverty might correlate poorly with actual living standards among the self-employed might be the fact that self-employed in general have greater opportunities than do regularly employed to obtain income illegally (undeclared income) (Alalehto & Larsson, Citation2012; Benedek & Lelkes, Citation2011; Engström & Holmlund, Citation2009; Shover & Hochstetler, Citation2006). Alalehto and Larsson (Citation2012) reported that as many as 47% of the self-employed in Sweden had committed VAT-crime during the last 5 years. These kinds of income resources (or lack of expenses) are not reported into administrative registers, and it is reasonable to assume that this kind of income is not reported in any greater extent in surveys either (Engström & Holmlund Citation2009; Hurst, Li, & Pugsley, Citation2014). Based on income reported in a survey, Engström and Holmlund (Citation2009) estimated that about 30% of the incomes of the self-employed in Sweden were not declared.

Yet another reason why income poverty might correlate poorly with living standards among the self-employed is that some of the household consumption may be financed by the firm. Even self-employed with fairly low income might have access to items which may be of importance in order for individuals to be fully included in society (e.g. cars, mobile phones, and computers through their firms) (Bradbury, Citation1997; Phipps, Citation2000).

The socio-demography of the self-employed

The socio-demographic composition of the self-employed (and other-related characteristics) might also affect income poverty and living standards. Based on previous research, we identify a number of such characteristics relevant when examining the relationship between income poverty and living standards. The first one is gender. Men and women might have different motivations to become self-employed: to earn money is more often an important motivating factor for men while balancing work and family is more often a motivating factor among women (Arum & Mueller, Citation2004; Dawson, Henley, & Latreille, Citation2009; Hundley, Citation2000). Men and women also tend to work in different industries, and it is more common for self-employed men than self-employed women to have employees (Arum & Mueller, Citation2004). Previous findings also indicate that women's income from self-employment may be of less importance for their total household income (Hundley, Citation2000).

Another relevant socio-demographic factor is age. Previous research has found that the average age is substantially higher among the self-employed than among the regularly employed (Blanchflower, Citation2000). Older people are in general well established on the labor market and/or possibly less dependent on regular earnings due to having more savings and possession of other assets. Older people may therefore be less dependent on a regular cash flow, implying that their living standard might be relatively high even if their income is low.

Educational attainment might also be related to income poverty and living standards. Previous research indicates that self-employment is more common among individuals with either a high or a low level of education than among people with secondary educational attainment (Blanchflower, Citation2000). The differences between the self-employed and employees in terms of poverty may thus partly be related to differences in human capital.

Some scholars have also suggested that immigrants may face a risk of being discriminated/excluded from the ordinary labor market and thus“pushed” into self-employment (Andersson & Wadensjö, Citation2004a; Clark & Drinkwater, Citation1998; Hammarstedt, Citation2006). Immigrant self-employed might therefore have lower income than native self-employed (in Sweden, especially self-employed from non-European countries, see Hammarstedt, Citation2001; Citation2006), implying that it is important to take into account whether self-employed are immigrants or not when studying poverty among the self-employed.

Finally, income poverty and deprivation among the self-employed may result from an over-representation of the self-employed in certain industries in which profitability is low. Furthermore, different industries might provide different possibilities to obtain undeclared incomes (Shover & Hochstetler, Citation2006) and access to other material resources.

After this review of previous research on income poverty and living standards among the self-employed, we will now describe the data and methods applied in order to estimate income poverty rates and living standards among the self-employed and regularly employed in Sweden.

DATA

The data in the study are derived from the “Employment, material resources, and political preferences” (EMRAPP) postal survey conducted in 2011. The sample selection and administration of the survey were conducted by Statistics Sweden. In addition to the information based on the survey, the data set contains information on income of various kinds from both the respondents and the other members in the household—derived from administrative registers.

Since the self-employed constitute a small proportion of the total population, a non-proportional stratified sample was used to obtain a large enough sample of self-employed for detailed analysis. The sample thus comprises two strata: stratum 1 (2,483 respondents, response rate 42%) represents the self-employed in Sweden aged 25–64 years, and stratum 2 (2,642 respondents, response rate 44%) represents regular employees also aged 25–64 years. After a comparison of the achieved sample and the gross sample on a number of key variables such as, e.g. gender, age, and educational attainment, it was found that the achieved samples represent the population well.

The sampling frame for the self-employed was based on Statistics Sweden's business register. The sampling frame was thus restricted to individuals whose main source of income comes from self-employment. The sampling frame includes self-employed with and without employees. If the firm is collectively owned or a joint stocks company, the person operatively responsible has been defined as the self-employed.

MEASUREMENTS OF INCOME POVERTY AND LIVING STANDARDS

To capture income poverty, we use Eurostat's official measure of poverty risk, which defines poverty as living in a household with less than 60% of the median household income. The household income data are derived from administrative registers and contain incomes from labor, self-employment, and other kinds of income resources related to work as well as various kinds of social insurances. The household income data contain information from all individuals in the household and represents the total household income. The household income variable is based on the same principals and incomes as the household income data for Sweden used in EU-SILC (http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/microdata/eu_silc).

To take household constellation into account, we use the OECD-modified equivalence scale, where the respondent has value 1, every additional adult has 0.5, and every child has 0.3. Individuals aged 15 years and older are identified as adults and individuals below the age of 15 as children.

To capture living standard, we use a deprivation index, based on 29 consumption indicators. The concept of deprivation has its origin in Peter Townsends (Citation1979) work and has been further developed by Mack and Lansley (Citation1985) and others. The deprivation index is supposed to measure whether individuals lack resources to obtain the living conditions that are customary in the society they live in by capturing “those who have an enforced lack of socially perceived necessities” (Mack & Lansley, Citation1985, p. 45). This method to operationalize deprivation is based on a modified version of Mack and Lansley's (Citation1985) consensual poverty method. However, contrary to Mack and Lansley, we have not dichotomized the deprivation index based on particular criteria (in their case: deprivation was defined as not being able to afford three or more consumption items that more than 50% of the population considered important to have in order to be included in contemporary society). Instead, we use a weighted index based on the method developed by Halleröd (Citation1994). With this method, the respondents were given a list of various consumption items (both goods and services) (see Table A1) and, for each item, were asked whether or not they had it. If a respondent did not have the item, he/she was asked whether this was because he/she did not want it or could not afford it. Every item meeting this criterion was weighted in accordance with the proportion of the population possessing it. Not having an item because one cannot afford it gives a value for the item corresponding to the proportion of the population possessing it. All item scores were then summed into an additive deprivation index. The higher a respondent's score on the index, the more deprived the respondent is—and the lower living conditions do we assume that the respondent have.

As is usually the case with deprivation indexes, the reliability of the index is very high, with an overall Cronbach's alpha score of 0.91 (0.90 for the self-employed). The deprivation index has a range between 0 and 19.4 (mean=1.32; SD=2.47). When calculating the specific weight of each item, we used a modified representative dataset, where the self-employed were weighted down to the actual proportion they have in Sweden. This method of measuring deprivation has been used in a number of previous studies (e.g. Halleröd, Larsson, Gordon, & Ritakallio, Citation2006; Halleröd & Larsson, Citation2008a).

We assume that the deprivation index captures the complexity of an individual's living standard fairly well. Previous studies have indeed shown that the deprivation index correlates with several welfare problems, such as poor health, anxiety, crime victimization, unemployment problems, and loneliness (Halleröd & Larsson, Citation2008a; Whelan, Layte, Maître, & Nolan, Citation2001). Furthermore, the deprivation index measures well-being directly, while income poverty rather indicates well-being indirectly (Ringen, Citation1988).

CONTROL VARIABLES

An important part of our aim is to examine the significance of compositional effects for the relationship between income poverty and living standards among the self-employed and the regularly employed. We therefore include the following control variables in our models: “gender,” “age,” “education,” “region of birth,” “working time,” and “industry.” Age is measured in three categories: “25–35 years,” “36–49 years,” and “50–64 years.” Education distinguishes respondents having completed a “primary,” “secondary,” or “tertiary” education. The variable “region of birth” distinguishes respondents born in Sweden, Europe (not Sweden), and outside Europe.

Finally, since income poverty and deprivation among the self-employed might result from an over-representation of self-employed in certain industries in which profitability may be low, we also control for “industry.” The industry variable is based on SNI2007 (Swedish industry classification), which in turn corresponds with the EU standard NACE rev 1.1. We use a collapsed version of SNI2007 and differentiate between four broad industries: “agriculture,” “manufacturing,” “low-skilled service,” and “high-skilled service.” A small number of unclassified occupations are classified as “others.” The four broad industries are described in Table .

Table I Collapsed industry variable based on the Swedish Classification of Industries (SNI2007).

METHOD

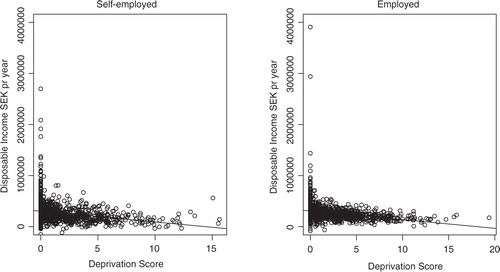

The distribution of the dependent variable, the deprivation index, has as expected a heavily left skewed distribution (most respondents thus have the value 0) among the self-employed as well as among the regularly employed as can be seen in . This implies that common regression techniques cannot be applied since such methods require a normally distributed dependent variable (Kleiber & Zeileis, Citation2008). To overcome this problem, the deprivation index can be understood as part of an unobserved normally distributed variable. This is what the Tobit regression method assumes. In a Tobit regression model, the relation between a latent (unobserved) normally distributed variable (y*) and the observed variable (y) is assumed. The latent variable (y*) is equal to the observed variable (y), if y exceeds the cut-off point for censoring. If y* is below the cut-off point, y is equal to the cut-off value. In the Tobit model, a likelihood function measures a linear relationship with the independent variables and y* for the metric data, and a probability model for the censored data (Amemiya, Citation1984).

It is important to keep in mind that the Tobit regression coefficients are linear (and additive) in relation to the latent response continuum, not to the observed measurement. Tobit regression models have been used in several previous studies on deprivation with good results (e.g. Halleröd et al., Citation2006). All analyses were performed using the statistical software R (R Core Team 2013). The package used to calculate the Tobit regression models is AER (Kleiber & Zeileis, Citation2008).

RESULTS

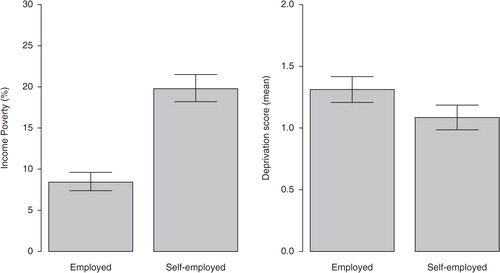

We begin the result section with descriptive statistics on the level of poverty and deprivation among self-employed and regularly employed in Sweden. As can be seen in , there are substantial differences in income poverty rate between these two categories. Almost 20% of the self-employed are income poor, while the corresponding figure among the regularly employed is 8%. This finding is well in line with previous research (Halleröd & Larsson, Citation2008b; Peña-Casas & Latta, Citation2004). However, when examining the deprivation scores among self-employed and regularly employed, the results show that the score is not higher for the self-employed than for the regularly employed as could be expected in the light of the high income poverty rate among the self-employed. The self-employed has a mean score of 1.08 on the deprivation index while the corresponding score among the regularly employed is 1.31 (the difference is however not statistically significant at the 95%-level). This result indicates that, even though the income poverty rate is higher among the self-employed, their actual living standard is clearly not worse compared with the regularly employed.

As discussed earlier, there might be several reasons why the income poverty rate is higher among the self-employed while deprivation scores are similar for self-employed and regularly employed. The self-employed might have certain characteristics affecting the relationship between income poverty and deprivation. For example, since the self-employed generally tend to be older than regularly employed, they might have access to more savings and assets implying that the annual income is of less importance for their living standard. In order to take such characteristics into account, we first have to examine the distribution of our control variables in relation to both employment types.

As can be seen in Table , there are some notable compositional differences between the self-employed and the regularly employed. The gender ratio is quite even among the regularly employed while men are significantly over-represented among the self-employed. The self-employed also tend to be older than the regularly employed. About 59% of the self-employed are older than 50 years of age, compared with about 42% among the regularly employed. When it comes to educational attainment, we find that the degree of education generally is lower among the self-employed than among the regularly employed. About 16% of the self-employed have only completed primary education, compared with 9% among the regularly employed. Conversely, about 33% of the self-employed have completed a tertiary education, compared with 52% among the regularly employed.

Table II Distribution and mean of control variables in sample.

Table also indicates that there are very small differences between the self-employed and the regularly employed in terms of “region of birth.” Regarding working time, we find that the self-employed tend to work longer hours than the regularly employed. The mean weekly hours are approximately 46 among the self-employed which can be compared to approximately 41 hours among the regularly employed.

Finally when examining the “industry” variable, we find substantial differences between the self-employed and the regularly employed. The self-employed are active in agriculture to a much greater extent than are the regularly employed (12% vs. 1%). Most interestingly, we find that it is more common among the self-employed to work in the low-skilled service industry while the opposite is true for the high-skilled service industry. About 30% of the self-employed are active in the low-skilled service industry compared to about 18% among the regularly employed.

To summarize, we find substantial compositional differences between the two segments of self-employed and regularly employed. These differences might indeed affect the relationship between income poverty and living standards. The next step of the analysis is consequently to specifically examine the differences in terms of living standards between income poor self-employed and income poor regularly employed. We therefore now apply two Tobit regression models in order to examine deprivation scores among income poor self-employed and income poor regularly employed before and after taking the compositional characteristics described above into account. Similar to OLS regression, the Tobit regression coefficients should be interpreted as linear and additive in relation to the response variable.

We already know from that the self-employed have a higher income poverty rate than the regularly employed, while the living standards of the self-employed and regularly employed are quite similar. In Table , we examine this “puzzling” result in more detail by comparing deprivation scores among income poor self-employed and income poor regularly employed. Model 1 in Table examines the crude relationship between employment type, income poverty and deprivation. The result shows that income poor self-employed have a deprivation score that is statistically significant lower than income poor regularly employed. The deprivation score among income poor self-employed is 1.92 points lower than the score among income poor regularly employed.

Table III The relationship between employment type, income poverty and deprivation. Tobit regression. Dependent variable: deprivation index.

Model 2 examines whether this relationship between income poverty and deprivation remains after taking compositional characteristics, “working time” and “industry” (the control variables) into account. When examining Model 2 in Table , we find that some of the differences in deprivation scores can be related to differences in the composition of the self-employed and the regularly employed. The difference in deprivation scores between income poor self-employed and income poor regularly employed is reduced from 1.92 to 1.06 in Model 2. However, the difference is still statistically significant suggesting that the relationship between income poverty and actual living standards is weaker among self-employed than among the regularly employed. Income poor self-employed generally have a higher living standard than income poor regularly employed independent of compositional characteristics.

Model 2 also shows that older individuals score lower on the deprivation index. Since the self-employed on average tend to be older than the regularly employed, it is likely that some of the difference between self-employed and the regularly employed in terms of their living standards is due to the age structure of both groups. Regarding the other control variables, it is worth emphasizing that we find few statistically significant differences in deprivation scores between the different categories of the “industry” variable. However, working in the low-skilled service sector is associated with a 0.83 increase in deprivation score compared to the reference category “high-skilled service.” As could be expected, the results also show that immigrants score particularly high on the deprivation index: respondents born outside of Europe score 2.84 scale points higher than respondents born in Sweden.

On the other hand, Model 2 also shows that income poor self-employed have a higher deprivation score than non-poor self-employed as well as non-poor regularly employed. This implies that income poverty does matter for the living standards of the self-employed. However, income poverty clearly is a less accurate indicator of the actual living standards of the self-employed compared to the regularly employed.

DISCUSSION

The aim of the study was to investigate whether the relationship between income poverty and actual living standards differs depending on employment relationship. This research question was motivated by previous empirical findings indicating that income poverty tend to be remarkably widespread among the self-employed. We used Eurostat's definition of income poverty risk and a deprivation index based on various kinds of consumption items as a measure of actual living standards. Our main findings suggest that income poverty is a poor measure of the actual living standards among the self-employed. Even though income poverty is more prevalent among the self-employed than among the regularly employed, we find no evidence suggesting that the self-employed in Sweden on average have a lower standard of living than the regularly employed. Furthermore, when specifically comparing the income poor self-employed with income poor regularly employed, we find that the self-employed have a statistically significant lower deprivation score than the regularly employed.

Part of the aim was also to examine the significance of compositional characteristics for the relationship between income poverty and living standards. We found that some of the difference in living standard between income poor self-employed and income poor regularly employed can be explained by the compositional characteristics of the groups. But the difference in deprivation scores remain statistically significant after controlling for “gender,” “age,” “education,” “country of birth,” “working time,” and “industry.” The remaining difference can most likely be explained by factors previously discussed in the literature review, such as for example higher levels of undeclared incomes and access to material resources through the firm among the self-employed. Our conclusion is therefore that poverty measures based on income data risks underestimating the actual living standard of the self-employed.

We need, however, to be somewhat careful when interpreting the results of this study. It might well be the case that the regularly employed who are income poor generally have a “deeper” poverty problem than the income poor self-employed. Our analysis says nothing about the severity of income poverty among self-employed and regularly employed. Another shortcoming of our study is of course that it is carried out in a single country. Comparative research is needed in the future in order to find out whether our empirical findings are robust across different institutional and cultural contexts, or whether contextual factors moderate the relationship between income poverty and living standards among self-employed. Nevertheless, when contrasting our findings with the ones from Australia presented by Bradbury (Citation1997), our conclusion is that there seems to be circumstances common to self-employed in very diverse contexts that affect the relationship between income poverty and actual living conditions in a similar way. Our findings thus suggest that reports of high poverty rates among the self-employed do not provide a full picture of the material conditions and living standards associated with self-employment.

Acknowledgements

The authors are listed in alphabetical order. This research was funded by the Swedish Foundation for Humanities and Social Sciences (Dnr P10-0411).

References

- Alalehto T., Larsson D. Vem är den ekonomiske brottslingen? En jämförelse mellan länder och brottstyper [Who is the economic criminal? A comparison between countries and types of crime]. Sociologisk Forskning. 2012; 49(1): 25–44.

- Amemiya T. Tobit models: a survey. Journal of Econometrics. 1984; 24(1): 3–61.

- Andersson P., Wadensjö E. Self-employed immigrants in Denmark and Sweden: A way to economic self-reliance?. 2004a. (IZA Discussion Paper No. 1130). Bonn, Germany: Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit (IZA)/Institute for the Study of Labour. Retrieved from http://ftp.iza.org/dp1130.pdf.

- Andersson P., Wadensjö E. Other forms of employment: Temporary employment agencies and self-employment (IZA Discussion Paper Series No. 1971). 2004b. Bonn, Germany: Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit (IZA)/Institute for the Study of Labour. Retrieved from http://ftp.iza.org/dp1971.pdf.

- Andersson P., Wadensjö E. Employees who become self-employed: Do labour income and wages have an impact? (IZA Discussion Paper Series No. 1971). 2006. Bonn, Germany: Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit (IZA)/Institute for the Study of Labour. Retrieved from http://econpapers.repec.org/paper/izaizadps/dp1971.htm.

- Arum R., Mueller W. Arum R., Mueller W. Findings and propositions. The reemergence of self-employment: A comparative study of self-employment dynamics and social inequality. 2004; Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Bardone L., Guio A.C. In-work poverty: New commonly agreed indicators at the EU level (Statistics in Focus, Population and Social Conditions No. 5/2005—Population and Living Conditions). 2005; Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities/Eurostat.

- Benedek D., Lelkes O. The distributional implications of income under-reporting in Hungary. Fiscal Studies. 2011; 32(4): 539–560.

- Blanchflower D.G. Self-employment in OECD countries. Labour Economics. 2000; 7(5): 471–505.

- Blanchflower D., Shadforth C. Entrepreneurship in the UK (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. ID 1628214). 2007; Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. Retrieved from http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1628214.

- Bradbury B. The living standards of the low income self-employed. Australian Economic Review. 1997; 30(4): 374–389.

- Carter S. The rewards of entrepreneurship: Exploring the incomes, wealth, and economic well-being of entrepreneurial households. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice. 2011; 35(1): 39–55.

- Clark K., Drinkwater S. Ethnicity and self-employment in Britain. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics. 1998; 60(3): 383–407.

- Davidsson P. Researching entrepreneurship. 2005; New York: Springer.

- Dawson C.J., Henley A., Latreille P.L. Why do individuals choose self-employment?. 2009; Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. Available at SSRN: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1336091.

- Engström P., Holmlund B. Tax evasion and self-employment in a high-tax country: evidence from Sweden. Applied Economics. 2009; 41(19): 2419–2430.

- European Commission. Flash Eurobarometer 174: SME access to finance. 2005; Brussels: Directorate General Enterprise and Industry.

- Fudge J. Self-Employment, women, and precarious work: The scope of labour protection. 2006; Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=896170.

- Halleröd B. A new approach to the direct consensual measurement of poverty. 1994. Social Policy Research Centre Discussion Paper, 50.

- Halleröd B., Larsson D. Poverty, welfare problems and social exclusion. International Journal of Social Welfare. 2008a; 17(1): 15–25.

- Halleröd B., Larsson D. Andreß H.-J., Lohmann H. In-work poverty in a transitional labour market: Sweden, 1988–2003. The working poor in Europe: employment, poverty and globalization. 2008b; Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing. 155–178.

- Halleröd B., Larsson D., Gordon D., Ritakallio V. Relative deprivation: A comparative analysis of Britain, Finland and Sweden. Journal of European Social Policy. 2006; 16(4): 328–345.

- Hamilton B.H. Does entrepreneurship pay? An empirical analysis of the returns to self-employment. Journal of Political Economy. 2000; 108(3): 604–631.

- Hammarstedt M. Immigrant self-employment in Sweden – its variation and some possible determinants. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development. 2001; 13(2): 147–161.

- Hammarstedt M. The predicted earnings differential and immigrant self-employment in Sweden. Applied Economics. 2006; 38(6): 619–630.

- Henrekson M., Stenkula M. Entrepreneurship and public policy. 2009; Stockholm: Research Institute of Industrial Economics.

- Hundley G. Male/female earnings differences in self-employment: The effects of marriage, children, and the household division of labor. Industrial and Labor Relations Review. 2000; 54(1): 95–114.

- Hurst E., Li G., Pugsley B. Are household surveys like tax forms? Evidence from income underreporting of the self-employed. Review of Economics and Statistics. 2014; 96(1): 19–33.

- Kalleberg A.L. Good jobs, bad jobs: The rise of polarized and precarious employment systems in the United States, 1970s–2000s. 2011; New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Kautonen T., Down S., Welter F., Vainio P., Palmroos J., Althoff K., Kolb S. “Involuntary self-employment” as a public policy issue: a cross-country European review. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research. 2010; 16(2): 112–129.

- Kleiber C., Zeileis A. Applied econometrics with R. 2008; New York: Springer.

- Koch M., Fritz M. Non-standard employment in Europe: Paradigms, prevalence and policy responses. 2013; Basingstoke, U.K.: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mack J., Lansley S. Poor Britain. 1985; London: Allen & Unwin.

- Maloney W.F. Fields G.S., Pfeffermann G.P. Informal self-employment: Poverty trap or decent alternative?. Pathways Out of Poverty. 2003; Boston: Kluwer Academic. 65–82.

- Peña-Casas R., Latta M. Working poor in the European Union. 2004. Dublin, Ireland: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions/Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- Phipps L. New communications technologies—A conduit for social inclusion. Information, Communication & Society. 2000; 3(1): 39–68.

- Rainnie A. Industrial relations in small firms. 1989; London: Routledge.

- Ringen S. Direct and indirect measures of poverty. Journal of Social Policy. 1988; 17(03): 351–365.

- Shane S.A. The illusions of entrepreneurship: The costly myths that entrepreneurs, investors, and policy makers live by. 2008; New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Shover N., Hochstetler A. Choosing white-collar crime. 2006; Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Townsend P. Poverty in the United Kingdom: A survey of household resources and standards of living. 1979; Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Vosko L.F. Precarious employment: Understanding labour market insecurity in Canada. 2006; Quèbec: McGill-Queen's Press-MQUP.

- Weir G. Self-employment in the UK labour market. Labour Market Trends. 2003; 111(9): 441–452.

- Whelan C.T., Layte R., Maître B., Nolan B. Income, deprivation, and economic strain: An analysis of the European Community Household Panel. European Sociological Review. 2001; 17(4): 357–372.