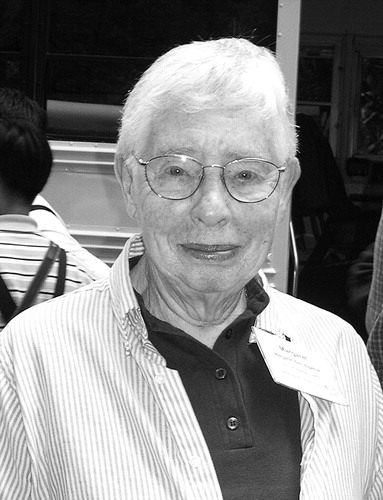

Margaret E. Barr Bigelow (), an internationally known mycologist, was born 16 Apr 1923 in Elkhorn, Manitoba. She spent her adult life working on a great diversity of fungi, daily observing more ascomycete diversity than most mycologists see in a lifetime. Margaret received a Bachelor of Science (1950) and Master of Science (1952) from the University of British Columbia. She was a student of Lewis E. Wehmeyer at the University of Michigan, where her 207-page dissertation, Taxonomic position of the genus Mycosphaerella as shown by comparative developmental studies, earned her a doctorate in 1956. In Ann Arbor she made lifelong friends among her fellow graduate students and married one of them. She and Howard Elson Bigelow were married in Jun 1956, just a week before they completed their doctorates at the University of Michigan.

No teaching positions were available the year they were married, so she and Howard spent a summer collecting fungi in northern Maine, and she along with Howard went to Montreal where she worked as a National Research Council fellow in the Botanical Institute at the University of Montreal. The next Sep (1957) Howard was hired as an instructor in botany at the University of Massachusetts. Because of rules against nepotism, Margaret could not have an official appointment in the department. However she was allowed to be part of a women’s auxiliary, which let her teach and do research for many years for modest compensation. Appointed year-to-year as an instructor beginning in 1957, she rose rapidly to the rank of professor after nepotism laws were revised, eventually serving as Ray Ethan Torrey Professor (1986–1989). She and Howard had been at the University of Massachusetts 30 y at the time of Howard’s death in 1987, and in 1989 Margaret moved to Sidney, British Columbia.

Jean Boise Cargill was a graduate student from 1979–1984, working on the systematics of the Loculoascomycete genus, Trematosphaeria. Upon first meeting Margaret, Jean asked her why she chose to study Loculoascomycetes; her reply was “because they are so impossible.” In a letter, Jean wrote that Margaret was a person whose “lack of pretense made her very accessible to professional colleagues around the globe. Margaret showed the same respect for the eccentric solo researcher as the lauded university professor. She instilled in me the notion that it is not the postmark that counts; it is the quality of the work.” Jean remembers that, in placing a high value on publishing one’s work, Margaret thought that “even the most brilliantly conceived notion was rendered worthless unless it made it into print.”

Margaret volunteered both time and money to her academic field. She served as program chairwoman for the Mycological Society of America (MSA) at the joint American Institute of Biological Sciences (AIBS) meetings of 1963 and again in 1973. In 1987 she was chairwoman of the entire AIBS meeting. She served as editor-in-chief of Mycologia, the journal of the MSA (1976–1980), and she served the Society as vice president (1979–1980) and president (1981–1982). In 1992 she was elected distinguished mycologist by the MSA. Although her primary society was the MSA, she also belonged to the American Institute of Biological Societies, International Association of Plant Taxonomists and British Mycological Society.

She established several endowments: The Howard E. and Margaret E. Barr Bigelow Endowed Fund for the Life Sciences Collection for biological sciences and geosciences journals, W.E.B. Du Bois Library, University of Massachusetts, and Howard E. Bigelow Mentor Fund and Margaret E. Barr Bigelow Mentor Fund for student travel to annual meetings of the MSA. In 1989 about 40 000 specimens of the University of Massachusetts Herbarium, which contained the bulk of Margaret’s and Howard’s collections, were transferred to the New York Botanical Garden. Other Margaret E. Barr collections are on deposit with the Canada Department of Agriculture, Ottawa (DAOM, about 5000 specimens) and the University of British Columbia (about 250 specimens), with a few types and later collections added to the holdings at New York. The unpublished notes and unidentified collections that remained following her death were transferred to the Field Museum in 2008.

She published about 150 scientific works that provided broad-scale coverage of many groups of ascomycetes. Because of her expertise she was sought as a collaborator by many mycologists. Several book-length works are among the most detailed references available and provide diagrams and descriptions of thousands of forgotten fungi belonging to groups that few people now know. Her volumes on the loculoascomycetes, pyrenomycetous hymenoascomycetes, Melanommatales and Pleosporales (CitationBarr 1987, CitationBarr 1990a, Citationb, Citationc) continue to be important references for North American collections as well as provide comparisons for specimens from around the world. After her retirement from the University of Massachusetts, she returned to her native British Columbia where she worked regular hours daily for many years on monographic studies of ascomycetes. She collaborated with a number of mycologists and offered her insights on taxon sampling for molecular studies in a modern context. Collectors from around the world sent her specimens for identifications. She studied fungi from as far away as Hawaii, China, Australia, Japan and Spain, as well as near her home in British Columbia. Her last paper was on a new species from oaks in western Canada, published late in 2007. Her vast experience put Margaret in a unique position to make transfers and to describe new species. She has been honored by having fungi named after her, including at least five genera (Barrella, Barria, Barrina, Barrmaelia, Mebarria), one fossil fungus (Margaretbarromyces) and species too numerous to list. Barr trained two doctoral students at the University of Massachusetts (Jean Boise-Cargill and Scott Schatz). After retirement she continued to serve as mentor to several generations of young mycologists. She died 1 Apr 2008 in Sidney, British Columbia.

One of us (Emory Simmons) appends a few paragraphs of more personal appreciation that are based on long years of collegial interaction and close friendship.

Margaret’s biography, curriculum vitae and list ofPUBLICations summarize a lifetime of intense application to a career of teaching at the university level and of probing into the habits and microscopic complexities of taxa in her chosen field of ascomycete taxonomy. The results were university students enlightened beyond their norm and, for mycologists, a towering production of insightful taxon delineation and classification throughout the species-to-ordinal range of her research interests.

Her career is well known in her professional circle, but it fails to animate either the generosity of her household or the unconcealed pleasure she exhibited among close friends. Margaret was a private person, almost shocked when anyone might expect some personal opinion instead of a professional one from her. Although she received many of the highest professional career awards and positions, she sought none of them and seldom produced little more than a “Why me?” response when honored. But she valued the honors, worked effectively in the positions and was confidently aware of her significance as a taxonomist.

The M. Barr, H. Bigelow and E. Simmons years of graduate school at the University of Michigan did not overlap. But we became acquainted through mycological activities when we all settled in Massachusetts—Margaret and Howard at the state university in Amherst and I at U.S. government laboratories in Natick, nearly at opposite ends of the state. After I moved my activities to the University of Massachusetts campus in 1974, we developed a closer relationship that involved house painting and other hands-on weekends at their restored farmhouse in hill-town Conway; annual Thanksgiving dinners, always with their graduate students at the table and usually with snow moving in toward evening; and occasionally dinner at one of the remarkably good restaurants in small hill or river towns scattered along the Connecticut River.

Margaret described herself at home as a good, plain cook, which in summer involved the products of her enormous vegetable garden. However her tastes when out on the town were quite otherwise. The unusual or inventive plate, with a tasty appetizer to start, was her choice as long as it was not lamb (“tastes wooly”) or rutabaga (which Howard’s Yankee genes always required at Thanksgiving dinner). And at their house, or mine, or elsewhere, it was always gin and tonic in the summer and Scotch whiskey when the weather cooled. After Margaret moved back to British Columbia, following Howard’s death, she and I frequently constituted a cohort at MSA annual meetings—related mycological interests, mutual friends and always found a good hotel lounge or restaurant table where we could indulge our appetites, our bits of gossip or comment, and any friend or student who happened by.

Two incidents, among many, reveal Margaret in a light rarely, if at all, seen by most of her professional colleagues. One centered on Amherst, the other on the Netherlands. Both are as characteristic of her personal nature as her long lists ofPUBLICations are of her professional career.

In autumn 1986, with their graduate students no longer on campus, the Bigelows had invited mutual friends from New York and Maryland, Clark Rogerson, Amy Rossman and Gary Samuels, up to Massachusetts for Thanksgiving Day. Simmons felt unable to spend the day in Conway because of a recent surgery and begged off the annual event. No problem, according to Margaret, who whipped up several traditional dishes (including Howard’s rutabagas) and transferred them and guests 20 miles to the Simmons fireside. It was a day of generosity of spirit and can-do by Margaret, as well as a day among close mycological friends that has lingered as a fond memory with all of us. And, of course, it snowed.

A second event, which sheds further light on the personal Margaret, took place in autumn 2006. I had been traveling to the Netherlands once or twice a year forPUBLICation work, with the next trip set for late September. When Margaret and I met at the MSA annual meeting in Quebec City that summer, I asked if she would like to join me in the Netherlands for a couple of weeks. She would have friends to see at Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures (CBS) while I worked, and on most other days we could ride the trains, do the museums, and in general live well. Her decision was prompt and unequivocal: yes.

We stayed at a small well-starred hotel I had found in a bosky suburb of Utrecht: quiet lounge and terrace for drinks, friendly service and a top-ranked restaurant. Work days at CBS were kept to a minimum. Then we rode the trains all over the Netherlands, just looking at the countryside and the occasional operational windmill (Margaret!); toured the Rotterdam harbor and Amsterdam canals (all eyes); trekked to Maastricht for Belgian chocolates (just an excuse); and provided her first engrossing view of Rembrandts, Vermeers, van Goghs, Frans Hals, Jan Steens and more. (Simmons usually located a bench with a view; Margaret, who had retained her walking habit, wandered alone and returned with wide, delighted eyes). We agreed that working retirees should always adopt this lifestyle.

My intent, with a self-serving aspect of choice, had been to afford an opportunity for Margaret to take a low-pressure vacation, which she never would do on her own: to visit the thriving CBS institution and renew ties with colleagues who were high on her list of cooperators; to experience the wonders of classic Dutch architecture, art and countryside; and to hang out comfortably, well-wined and -dined, and with the minor indulgence of her recently self-imposed but much-reduced total of four cigarettes a day. Her enjoyment throughout was obvious and, to use one of her choice words of quantity, a tad more than enough. The feeling was mutual. We all, as colleagues and friends, can be grateful to have shared the extended years of Margaret’s life.

SELECTEDPUBLICATIONS

References

- Barr ME. 1978. The Diaporthales in North America with emphasis on Gnomonia and its segregates. Mycol Mem 7:1–232.

- ———. 1987. Prodromus to class Loculoascomycetes. Amherst, Massachusetts: Publ by the author. 168 p.

- ———. 1990a. Melanommatales (Loculoascomycetes). N Am Flor, Ser II 13:1–129.

- ———. 1990b. Some dictyosporous genera and species of Pleosporales in North America. Mem NY Bot Gard 62: 1–92.

- ———. 1990c. Prodromus to nonlichenized, pyrenomycetous members of class Hymenoascomycetes. Mycotaxon 39:43–184.

- ———, Huhndorf SM. 2000. Loculoascomycetes. In: McLaughlin DJ, McLaughlin E, eds. The Mycota, Vol. VII. Springer-Verlag. p 283–305.

- ———, ———, Rogerson CT. 1996. The pyrenomycetes described by J.B. Ellis. Mem NY Bot Gard 79:1–137.

- Marincowitz S, Barr ME. 2007. Rhynchomeliola quercina, a new rostrate ascomycete from oak trees in western Canada. Mycotaxon 101:173–178.

- Réblová M, Barr ME, Samuels GJ. 1999. Chaetosphaeriaceae, a new family for Chaetosphaeria and its relatives. Sydowia 51:49–70.