Howard Whisler was a long-time friend and mycological colleague of mine. We shared many wonderful experiences as well as an interest in and excitement for zoosporic “fungi” for more than 50 y. He died 16 Sep 2007. Some of Howard’s contributions to mycology and invertebrate pathology will be reviewed here, along with some of the things one just had to enjoy or endure with Howard.

Howard was a true Californian, having been born in Oakland on 4 Feb 1931. His mother was of Welsh descent and his father of English descent; somehow those Welsh and English genes prevailed to make the son the delightful person many of us knew. Howard went to Berkeley schools where, as a seventh grader, he met Patricia Paine. Patty says she knew about Howard before they met, mostly due to his reputation for roaming the hills, collecting bugs and snakes and playing practical jokes on neighbors, teachers and anyone in authority. Howard and Patty were friends until their junior years in high school when a family move put Howard in Palo Alto, where he graduated from Palo Alto High School. He began his undergraduate studies at Oregon State University in 1949, but after 2 y Howard decided forestry was not for him. He returned to California and entered the University of California at Berkeley. Clearly he had other interests there, and in 1952 he and Patty married. For more than 50 y she and Howard traveled around the world with Howard chasing black flies, mosquitoes, worms and anything else that might be a home for aquatic fungi and other interesting organisms associated with invertebrates.

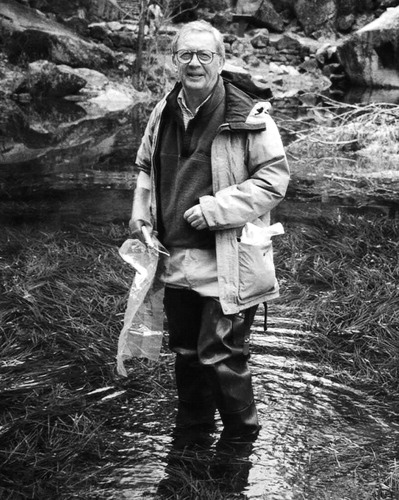

Howard’s undergraduate major at Berkeley was plant pathology, but a fascination with fungi led him to Ralph Emerson’s course on Phycomycetes; Howard was hooked. Emerson was convinced that some of the aquatic fungi he knew from New England, namely Monoblepharis, could not and would not be found in relatively arid California. This undergraduate, who had learned how to isolate zoosporic fungi from the master, was not one to believe anything was impossible. Howard proceeded to see whether Emerson was right by collecting twigs from Mirror Lake in Yosemite National Park (); Monoblepharis grew from the bark of these twigs a few days later. Howard’s later scientific accomplishments were characterized by persistence in areas where others had given up or believed the challenge was impossible.

By the time Howard received the B.S. degree a son, Jack (born in 1953), was on the way and there were other obligations to be met. This was the time of the Korean War and Howard, having been in the Air Force ROTC program, had an obligation to meet. He entered the Air Force in 1954 expecting to become a pilot. However this didn’t work out and Howard went to Africa for a period. A daughter, Jane, was born in Mar 1955, by which time Howard had been sent to Aviano, Italy, as the supply officer for the Air Force base there. In May 1955 Patty, Jack and 2 mo old Jane joined Howard in Aviano. This was the beginning of Howard’s and Patty’s long love affair with Europe and world travel. By this time, Sep 1955, I had enrolled at Berkeley to study for the Ph.D. with Ralph Emerson. My job that first year was taking care of the Emerson culture collection, so I spent a lot of time in Emerson’s small laboratory next to his office. On a daily basis I heard about the wonder boy of zoosporic fungi who would be coming to the laboratory in January when he got out of the Air Force. He came but, unlike the rest of us who smoked cigarettes in those days, Howard smoked cigars and snuffed them out or left them burning in the ashtrays in Emerson’s lab. Emerson, himself a partially reformed smoker, couldn’t stand the cigars that smelled and turned the air blue. He threw Howard’s cigars, ashtrays and all, into the waste can. It was then that I knew the wonder boy was going to be one of us, even though he was purported to perform miracles at times. After Emerson’s death Howard and I somehow each ended up with one of those ash trays.

Howard continued to roam the hills and mountains of California but spent an equal amount of time in rice paddies, vernal pools and most memorable to me the Sacramento River Delta. I can still see him knee deep in mud picking up sticks and collecting water samples while I stood on the banks swatting flies and mosquitoes. It was during his graduate student days that Howard developed his life-long interest in fungi associated with invertebrates. His thesis concerned entomogenous fungi and chytridiomycetes. One of these organisms, now known as the mesomycetozoean Amoebidium parasiticum, became the subject of several papers in subsequent years as Howard developed an expertise in various disciplines that contributed to his studies on the biology of fungi and other fungus-like organisms. After receiving the Ph.D. in 1960 Howard and family were off to Europe again for a year of postdoctoral study with Drs Jehanne-Françoise Manier and Odette Tuzet at the University of Montpelier in the south of France. Patty became proficient in French, and they returned to France and other European countries many times in the years that followed.

After study in France it was off to Montreal in 1961 to become an assistant professor of botany at McGill University in a department chaired by Charlie Wilson, who had been a sabbatical replacement in Berkeley in 1957 while Emerson was in Costa Rica. During their time at McGill Howard and Patty traveled to our home in Rhode Island with bottles of trichomycete-infested black flies; this would not be the last time that Howard visited us with a living menagerie or I had the opportunity to help feed his colonies of flies, mosquitoes, etc. In 1963 Howard moved to the Department of Botany, University of Washington at Seattle; he remained there until his retirement as a full professor in 1999.

One of Howard’s duties at the University of Washington was to develop a marine mycology course and fungal research program at the Friday Harbor Marine Laboratory. I, by this time having moved from Brown University to a faculty position at Berkeley, was lucky enough during the summer of 1964 to join Howard in teaching the first marine mycology course at the Friday Harbor laboratories. David Porter, the first of many graduate students who worked with Howard at the University of Washington, was our teaching assistant. It became clear during this course that Howard and his students and collaborators would be studying the biology of many organisms associated with invertebrates. He regularly attended meetings of the Invertebrate Pathology Society. Many of hisPUBLICations and those of his students on these marine organisms appeared between 1963 and 1973. Howard was not one to micromanage the work of his students. Instead they were given the space and necessary support for their research before being allowed to find their own way and make the choices that fit their respective goals.

As graduate students we had heard much from Emerson about an important fungal pathogen of mosquitoes and the potential that it might have for controlling the mosquitoes that were responsible for the spread of malaria. I’m not sure exactly when Howard launched his studies of Coelomomyces spp., but after his 1972PUBLICation with Joe Shemanchuk of the Lethbridge Research Center in Alberta, Canada, and Linda Travland (CitationWhisler et al 1972), this fungus was a major player in Whisler’s research (CitationWhisler et al 1974, Citation1975). I would be hard put to say what I think was Howard’s most significant research finding, but his discovery of an alternate host for Coelomomyces and, as a result the sexual stages of the life cycle, has to be very high on any list. In the many years I attended meetings related to mycology, the only time I ever remember the author of a contributed paper receiving a standing ovation was when Howard reported the findings that he made with Steve Zebold and Joe Shemanchuk at the MSA meeting in Tempe, Arizona, in Jun 1974. For those who might look for a record of the remarkable paper, there is none in the program; instead a paper on transmission electron microscopy on a member of the Laboulbeniales was listed. Although the room-full of mycologists expected to hear about development of the insect ectoparasite, the audience was rapt with excitement when Howard announced his title change. Many papers on the biology of Coelomomyces spp. would follow, and Howard collected the fungus everywhere he could from the Philippines to piles of discarded tires in Louisiana. Although he did not succeed in growing Coelomomyces spp. in axenic culture he never stopped trying, as was true in so many other ventures.

While he continued his work on fungi associated with invertebrates he was not able to forget the challenges first posed by Monoblepharis when he was an undergraduate. He and Emerson had been able to grow pure cultures of the fungus but never achieved more than mycelial development. Monoblepharis has one of the most beautiful sexual stages of any zoosporic fungus, and Howard persisted until he succeeded in getting this fungus to produce the sexual stage in the laboratory. He isolated and manipulated culture after culture until in the mid-80s he found isolates in which he could control and study the development of the sexual stages. The work resulted in a film, “Sexuality of Monoblepharis”, and papers published by his student CitationMarek (1984) and CitationWhisler and Marek (1987).

Howard was active in MSA as an interested member and councilor. He also had a unique role as chairman of an ad hoc self-study committee which I talked him into on 11 Dec 1975 (see letter from Fuller in CitationMSA Newsletter 26[2]). Other members of the committee included Bob Lichtwardt, Solomon Bartnicki-Garcia and Jack Rogers. The group was kept small “to facilitate communication and necessary meetings of the committee.” It was formed at a time when only a few years previously the MSA Board of Councilors had “reaffirmed a decision not to publish abstracts of papers presented at society meetings (CitationMSA Newsletter 21[2] 1970.” It also was a time when a number of younger members had many suggestions to improve the society, including changes in the journal.

The Whisler report, as it came to be known, was the subject of a long MSA council meeting conducted by society President Howard Bigelow and held at the 2nd International Mycological Congress in Tampa, Florida. The first council session began Sunday 28 Aug 1977 at 5 p.m., and to discuss the Whisler report a second meeting was called on Thursday Sep 1. The meeting lasted until 10 p.m. when the group had to move to a different room; they adjourned Friday at 12:15 a.m. (CitationMSA Newsletter 28[2] 1977). Several current members who were there remember that the meeting was long!

Rogers became president after the Tampa meeting, and his president’s letter summarized the recommendations approved from the Whisler report: (i)PUBLICation of abstracts in the CitationMSA Newsletter; (ii) establishment of an ad hoc teaching committee; (iii) negotiation with the New York Botanical Garden to increase the editorial board of Mycologia to 15; and (iv) establishment of an award to be given periodically to an outstanding mycologist (CitationMSA Newsletter 28[2] 1970). Some of the discussions were contentious and involved plans to change the dimensions of the journal. The failure to move quickly on this proposal led in part to a renegade move for a new journal with larger page size. The council eventually tabled all other items of the committee report with a vote of 8-0-2. Abstracts appeared in the CitationMSA Newsletter (29[1] 1978) before the Athens, Georgia, meeting Aug 1978. Over the years other changes suggested in the Whisler report have been implemented, albeit slowly in some cases, and MSA has been improved as a society.

Joe Ammirati of the University of Washington has published a detailed biographical sketch of Howard that emphasizes his research achievements and includes a complete bibliography (CitationAmmirati 2008). Here I have tried to capture some of the person I enjoyed knowing for so many years. Howard was a unique individual who had a great love for nature and the organisms he studied. He was often so wrapped up in these studies that he never found time to answer letters or send out reprints; it was a lot easier to pick up the telephone and talk with his colleagues and former students. A handwritten letter from Howard is said to have sold for a high price at a recent mycological society auction. On the one hand Howard conducted many remarkable studies that he shared throughPUBLICation. On the other hand I am certain there are many secrets of the organisms he studied that were not revealed because he was so busy solving other difficult problems. Thaxter, Weston, Emerson and many others of the Thaxter mycological lineage would agree that Howard left his mark on mycology and invertebrate pathology.

I thank Meredith Blackwell for her continuing contributions and coaxing that resulted in this tribute to Howard. I am also grateful for the help of Patty Whisler and David Porter who verified and added to the accuracy of the final result.

LITERATURE CITED

- Ammirati JF. 2008. Howard Clinton Whisler—University of Washington. N Am Fungi 3:1–11.

- Marek LE. 1984. Light affects in vitro development of gametangia and sporangia of Monoblepharis macrandra. Mycologia 76:420–425.

- MSA Newsletter. http://msafungi.org/inoculum

- Whisler HC, Marek LE. 1987. Monoblepharis macrandra. In: Fuller MS, Jaworski A, eds. Zoosporic fungi in teaching and research. Athens, Georgia: Southeastern Publishing Co. p 54–55.

- ———, Shemanchuk JA, Travland LB. 1972. Germination of the resistant sporangia of Coelomomyces psorophorae. J Invertebr Pathol 19:139–147.

- ———, Zebold SL, Shemanchuk JA. 1974. Alternate host for mosquito parasite Coelomomyces. Nature 251:715–716.

- ———, ———, ———. 1975. Life history of Coelomomyces psorophorae. Nat Acad Sci USA 72:693–696.