Abstract

Collections of a pleurotoid fungus from dead aspen in eastern Russia were initially identified as Lentinus sp., then as Phyllotopsis nidulans. DNA sequencing of cultures derived from these specimens using the nuclear ribosomal 28S (nrLSU) and nuclear ribosomal ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 regions (nrITS) showed that they were neither Lentinus nor Phyllotopsis and were not related to other pleurotoid genera Hohenbuehelia and Pleurotus. Subsequent investigation showed that the Russian fungus was the same as Pleurotus vetlinianus described from Poland. A new genus, Lignomyces, is described and characterized and L. vetlinianus comb. nov. is proposed.

Introduction

In a study comparing material of Phyllotopsis nidulans from Europe and North America dikaryon cultures were received by the Tennessee laboratory from the Komarov Botanical Institute. Along with others these were transferred and sequenced with the nuclear ribosomal ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 region (nrITS) and the nuclear ribosomal 28S (nrLSU) regions. These sequences demonstrated that two cultures, LE-BIN 2335 and LE-BIN 2339, did not represent P. nidulans and further that they did not correspond to any sequences in GenBank or the TENN sequence database. Cultures readily fruited on malt extract agar medium and rye grain. Further investigation revealed that specimens of Pleurotus vetlinianus Domański from Poland matched the unidentified fungus morphologically, but, although the species had been named and described, its taxonomic position was unknown (CitationThorn and Barron 1986). Nonetheless Moser recombined the species epithet in Resupinatus (CitationMoser 1979). Finally a new collection identified as P. vetlinianus was contributed from the general area in Poland in which P. vetlinianus had been found, furnishing an opportunity to compare morphology and molecular analyses. Collections and cultures of the fungus are described, illustrated and placed phylogenetically, and a new genus name is proposed for the species.

Materials and methods

Specimen collection

Specimens were collected in 2008 on the mycological foray at the Zvenigorod Biological Station of Moscow State University (Russia) in the vicinity of Sharapovskoye swamp in spruce-pine forest with poplar and birch. Basidiomata fruited on dead Populus tremula trees. Two specimens were collected from adjacent trees and identified as Lentinus sp. Two dikaryon cultures were obtained from these specimens. Later the specimens were identified as Phyllotopsis nidulans and the cultures 2335 and 2339 were deposited in the Komarov Botanical Institute Basidiomycetes Culture Collection (LE-BIN) under this name. Preserved voucher basidiomata were deposited in the Mycological Herbarium of the Komarov Botanical Institute (LE 265212, LE 254591, respectively). Similar basidiomata were collected in 2012 (LE 287742, LE 287743) and 2014 (LE 287550) in Novgorod region, also on dead aspen and a culture LE-BIN 3253 was obtained from the 2014 specimen. Culture growth and morphology were studied in 90 mm Petri plates on beer-wort agar (BWA) and MEA and PDA with standard methods and terminology.

DNA sequence analyses

Molecular procedures for DNA extraction and Sanger sequencing of nrITS and nrLSU regions were as described in CitationHughes et al. (2013). Sequences were blasted against GenBank accessions and our personal sequence database. Closest matches plus putatively related fungi based on morphology (Pleurotus, Pleurocybella, Phyllotopsis) were downloaded, and a series of preliminary phylogenetic analyses were performed to identify putative family associations. Sequences initially were aligned in GCG (CitationGCG 2000), imported into Geneiois (CitationGeneious 2005) and re-aligned with MAFFT (CitationKatoh et al. 2002). Sequences generated as part of this project are included herein (supplementary table I). Alignments were deposited in TreeBASE at http://purl.org/phylo/treebase/phylows/study/TB2:S17321.

Microscopic analyses

Microscopic analyses were done with a Nikon SMZ-2T dissecting microscope and an Olympus BX60 compound instrument with no stains but under phase contrast microscopy (PhC). Culture microscopy was done with Carl Zeiss Axio Imager A1, Axio Scope A1 and Stemi 2000-CS. In the text below color names in quotation marks are from CitationRidgway (1912) and those expressed with alphanumeric codes are from CitationKornerup and Wanscher (1967).

In vitro macrochemical reactions

Three dikaryon Lignomyces cultures, LE-BIN 2335, 2339 and 3253, were used for macrochemical assays. Laccase and tyrosinase production was studied at weeks 2, 3 and 4 by spot tests using syringaldazine, guiacol and l-tyrosine as substrates (CitationMarr 1979, CitationFedorova et al. 2013). Reactions were evaluated at 5, 15, 30 min, 3 and 24 h as positive (from ± = weakly positive to +++ = strongly positive) or negative (−). Crystals were observed at week 6. Cyclic compounds production was detected with the “newspaper” Wieland test (CitationWieland 1986): a small piece of mycelium was squeezed out on the unprinted edge of an old newspaper containing wood fibers and left to dry. Then several drops of 6N HCl were added to the spot. The reaction was observed after 5–10 min. A change to blue indicated the presence of cyclic compounds.

To induce fruiting, cultures were grown separately on rye grain and birch sawdust. Rye grain was autoclaved in polycarbonate/polypropylene plant tissue culture containers with plastic lids. Birch sawdust and wheat bran (3 : 1, respectively) were mixed with boiling water until the substrate was damp. The substrate was autoclaved in glass beakers covered with aluminum foil. Cultures on MEA medium were diced under sterile conditions and mixed with sterilized rye grain or sawdust substrate. Inoculated beakers were incubated in darkness at room temperature for 3 wk, then removed to a Sanyo growth chamber (20 C, 2000 lx, 90% humidity). Lids were removed when the culture began to form visible basidiomata.

Isolation of single-basidiospore isolates (SBIs)

No viable spore print was supplied with herbarium material, but the original discovery of Lignomyces was from dikaryon cultures of two collections, LE-BIN 2335 and LE-BIN 2339. These dikaryon cultures were fruited on rye grain and formed vigorous, sporulating basidiomata. From one of these basidiomata, LE-BIN 2339, spores were dropped on sterile aluminum foil. A small portion of the resulting spore print was suspended in sterile distilled water and diluted at 1 : 10 ratios through three dilutions. One milliliter of each dilution was spread over MEA. Although spore germination rate was low (i.e. 1 : 100,000) in these spreads, 16 putative SBIs were harvested over 3 wk. When colony growth reached ca. 1 cm diam, small portions of mycelium was assayed for presence of clamp connections, and therefore putative dikaryon nuclear condition.

Taxonomy

Taxonomic treatment

Lignomyces R.H. Petersen & Zmitr. gen. nov.

MycoBank MB811172

Typification: Pleurotus vetlinianus Domański. Acta Soc. Bot. Poloniae 33(2):243. 1964.

Etymology: lignum (L.), signifying fruiting habit on wood, the hard, woody texture of basidiomata when dried and production of wood-degrading enzymes + -myces (Gr.), fungus.

Genus diagnosis: Basidiomata pleurotoid, of a size comparable to those of Pleurotus species. Pileus trama duplex, with upper trama moist, of non-gelatinized hyphae exhibiting conspicuous clamp connections, juxtaposed to lamellae a gelatinized layer, subhyaline when fresh, becoming ochraceous and glassy upon drying. Lamellar trama gelatinized, with hyphal walls swelling significantly when fresh and moist. Hymenium exhibiting common cystidia, elongate-fusiform in the type species, with homogeneous contents and basal clamp connections.

Lignomyces vetlinianus (Domański) R.H. Petersen & Zmitr., comb. nov. Figs. –

Figs. 1–5. Lignomyces vetlinianus basidiomata. 1. ASN 2012-51(1). 2. ASN 2012-51.5. 3. ASN 25.07.2012. 4. LE 265212. 5. ASN 06.08.2012-2. Standard bars = 5 cm.

MycoBank MB811173

≡ Pleurotus vetlinianus Domański. Acta Soc. Bot. Poloniae 33:243. 1964.

≡ Resupinatus vetlinianus (Domański) M.M. Moser (as ‘wetlinianus’). Sydowia (ser. 2) 8:275. 1979.

Species description: Basidiomata (from dried basidiomata or photos of fresh material ) pleurotoid-pseudostipitate, not effuse-reflexed, arising deep within woody substratum root-like base, reniform, orbiculate, auriform, dimidiate to broadly cuneiform with inrolled margin. Pileus 25–70(−100) × 30–80(−150) mm; pileus surface initially pubescent (), becoming hispid or furry (; superficial “spikes” 1–2 mm high at maturity, initially off-white, mellowing to cream colored, perhaps near “light ochraceous buff” (5A4), sometimes with isabelline tint; margin () thin, initially inrolled, moderately undulate, ivory white. Pileus trama white, when dried revealing delicately marbled texture; gelatinized layer juxtaposed to lamellae, 1–2 mm thick, hardly detectable when fresh but when dried becoming glassy and dark ochraceous. Lamellae () 1–7(−10) mm broad, thin (i.e. bladelike), off-white, entire (not serrate but serrulate at the base in old basidiomata), easily cracked, gradually narrowing downward on stipe, convergent on upper stipe, when dried becoming somewhat cartilaginous and exhibiting a glassy (gelatinized) trama (50×); partial veil absent; lamellulae () in 2–3 ranks. Stipe portion () tough-fleshy becoming hard-spongy, narrowing from the broadly cuneiform pileus, 3–25 mm thick, initially soaked, becoming dry and hard; stipe flesh white when fresh, macroscopically homogeneous, bruising ivory with weak rose or isabelline tints; stipe base slightly enlarged, but insertion in woody substrate apparently narrowed. Odor strong, slightly rancid; flavor reminiscent of Postia tephroleuca.

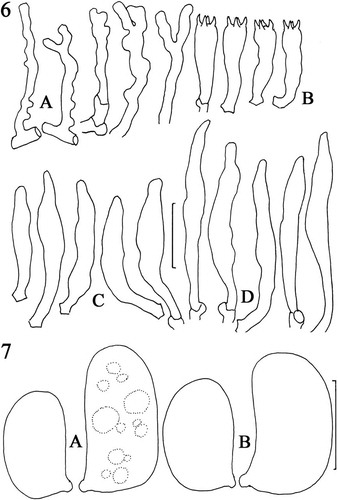

Habitat

On standing or fallen dead beech (Fagus sylvatica) or aspen (Populus tremula) in mixed conifer-deciduous forest. Russian locations all apparently near swamp.

Pileipellis composed of radially arranged hyphae similar to those of stipe trama, with slender hyphal type dominant, firm-walled, frequently clamped; hyphae of cutis repent but with frequent erect hyphal termini () ranging from straight, firm-walled, to somewhat gnarled and often branched. Hyphae of superficial pileipellis −5 μm diam near origin, gradually tapering throughout length to <1 μm diam, apparently firm-walled (wall thickness not measurable, refringence dictated by orientation to light source [PhC]; not uniformly refringent due to wall thickness), rarely forked; clamp connections occasional, conspicuous. Pileus tramal hyphae 2.5–10.5 μm diam, tightly interwoven, moderately thick-walled (wall −0.5 μm thick; generative) to gelatinized (appearing pseudoskeletal, often obscuring cell lumen; gelatinized wall irregular in depth, −1 μm thick, hyaline), inamyloid, acyanophilous, conspicuously clamped; pseudoclamps and irregular ampulliform swellings present. Also present are utriform swellings (−45 μm diam) stalked, thin-walled, easily semicollapsed; contents heterogeneous with many small, scattered granules and one to several larger, refringent, crystalline inclusions. Hyphae of gelatinous layer 6–17 μm diam, parallel, coherent, generally radially oriented, with gelatinized wall (appearing thick-walled but without wall delineation; gelatinization −3 μm thick, hyaline, obscuring cell lumen or lumen capillary [a single fine line]); clamp connections not observed on gelatinized hyphae. Lamellar trama generally radially oriented, gelatinized, quickly swelling in KOH, interwoven; hyphae 1.7–3.2(−7) μm diam, thin- to firm-walled, conspicuously clamped. Subhymenium tightly interwoven, hardly gelatinized; hyphae 2–2.5 μm diam, frequently branched, thin-walled, frequently clamped, producing basidioles and basidia as bouquets; contents homogeneous to including scattered small guttules. Basidia () 25–34 × 6–8 μm, clavate, arising from a clamp connection, four-sterigmate (sterigmata −5 μm long); contents multiguttulate; guttules refringent, scattered, usually large at basidial base and apex. Pleurocystidia () infrequent to common, (20–)39–65 × (3.8–)6–9 μm, usually narrowly fusiform, but also hyphoid, ventricose or obscurely tibiiform, thin-walled, hyaline, arising from subhymenium, extending beyond hymenium 10–35 μm; contents subrefringent, homogeneous. Lamella edge fertile with scattered cheilocystidia; cheilocystidia () (22–)49–66(–80) × (3.8–)5–8 μm, protruding beyond hymenium 10–20 μm, narrowly fusiform to cylindrical, easily disarticulated from source (no clamp seen), hyaline; contents subrefringent, homogeneous. Basidiospores () (5.2–)7.5–8.7 × (2.8–)3.5–4.5(–5) μm (M = 7.3 × 3.9 μm; Q = 1.67–2.14; Qm = 1.89; Lm = 7.35 μm), plumpellipsoid, occasionally with a suggestion of concavity (slightly reniform), thin-walled, hyaline, inamyloid, non-dextrinoid; contents with several scattered, refringent guttules (PhC); wall weakly cyanophilous. Longitudinal scalp of stipe trama: hyphal construction pseudodimitic, of two hyphal types: (i) flagelliform, slender (1.5–4 μm diam), firm- to thick-walled (wall −0.5 μm thick), hyaline, arising from a clamped septum, occasionally dichotomously branched with a clamp connection on both branches, conspicuously clamped, with terminus not observed (i.e. whether tapered apically or reverting to a wider hypha at a clamp connection), apparently locally common but not forming a discrete tissue; and (ii) stouter (5–8 μm diam), thick-walled (wall −0.7 μm thick), hyaline, meandering or gnarled, occasionally septate and then clamped, tightly interwoven.

Figs. 6, 7. Lignomyces vetlinianus, micromorphology. A. Hyphae emergent from young pileipellis. B. Basidia. C. Pleurocystidia. D. Cheilocystidia. LE 254591. Standard bar = 20 μm. 7. Basidiospores. A. Spores from dried in vivo basidiome. B. Spores from in vitro basidiome. LE 254591. Standard bar = 5 μm.

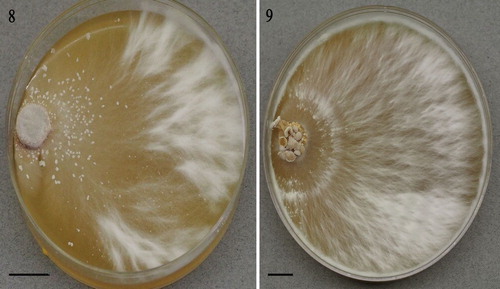

Culture morphology

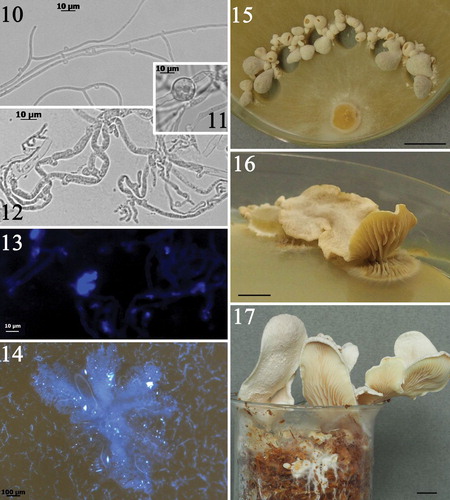

Strains LE-BIN 2335 and 3253 presented somewhat different colony morphologies on BWA (), both growth rate (covered 90 mm plates in 5 and 4 wk, respectively) and somewhat plumose. Advancing zone hyphae slender, thin-walled, branched, with clamp connections (). Aerial hyphae (1.5–5 μm diam) polymorphic, occasionally producing intercalary swellings (). Agar-surface hyphae turgid, often variously swollen, conspicuously clamped (). On MEA, numerous crystals were observed to be luminescent in UV light ().

Figs. 8, 9. Lignomyces vetlinianus culture macromorphology on BWA: 8. Strain LE-BIN 2335; 9. LE-BIN 3253. Bars = 10 mm.

Figs. 10–17. Lignomyces vetlinianus culture characteristics. 10−13. Micromorphology: 10. Margin hyphae. Note prominent clamp connections. LE-BIN 2339. 11. Swelling on aerial hyphae, LE-BIN 2335. 12. Agar-surface hyphae. Note prominent clamp connections. LE-BIN 2335. 13. Crystals on hyphae glowing in UV (no staining added). Bar = 10 μm. LE-BIN 3253. 14. Crystals on mycelial mat. Bar = 100 μm. LE-BIN 2339. 15. Immature basidiomata on cut edges of agar. LE-BIN 2339. Bar = 10 mm. 16. Mature basidioma producing abundant spore print on agar surface, LE-BIN 2339. Bar = 10 mm. 17. Basidiomata produced on birch sawdust, LE-BIN 3253. Bar = 10 mm.

In vitro macrochemical tests

After 2 wk growth on BWA all Lignomyces strains demonstrated positive reaction for laccases (color reactions on syringaldazine and guiacol from ± to +++ depending on checking time). Tests for tyrosinase produced negative results. Wieland “newspaper” test had strong indigo coloration revealing the presence of cyclic compounds both in mycelium and basidiomata produced in vitro.

Fruiting in culture

Cultures were highly morphogenic, forming primordia on BWA and MEA within 1 wk of inoculation. Initiation of fruiting started from the inoculum block, then occurred at the edges of the plates and were especially numerous on cut edges of the colony (). In 3–4 wk pale flesh-colored pleurotoid basidiomata deposited an abundant pale flesh-color spore print (). On birch sawdust, strains fruited within 3 wk after moving the overgrown sawdust to an illuminated growth chamber ().

Basidiomata from rye grain inoculations

Basidiomata pseudostipitate, up to 45 mm broad. Pileus chalk white, finely silky downward, delicately rivulose outward; margin tightly inrolled. Lamellae crowded, shallow, sharp (not thick), inward “light ochraceous buff” (5A4) outward “pale pinkish cinnamon” (5A2) (almost no pinkish or orange pigmentation). Spore prints off-white. All hyphae consistently clamped. Lamellar trama minimal, but hyphae firm- to thick-walled (wall −0.5 μm thick), somewhat sinuate, producing hymenial structures as sympodial branches. Mature basidia not observed. Immature basidia approx. 30–35 × 4 μm, clavate, clamped; contents multiguttulate. Pleurocystidial structures deduced from the sizes of basidioles: 39– 52 × 4.5–7.5 μm, clavatefusoid with somewhat narrowed apex, clamped. Cheilocystidial structures common, 56–91 × 2.5–6 μm, clamped, hyaline, firm-walled. Basidiospores 6.5–7.5(−8) × 4–.5 μm (M = 7.0 × 4.32 μm; Q = 1.56–1.78; Qm = 1.62), broadly cylindrical, ellipsoid to occasionally subphaseoliform, smooth, thin-walled.

Mating system experiments

When 12 SBIs selected for a self-cross experiment were paired in all combinations, a tetrapolar mating system was revealed. “Barrage” and “flat” reactions were extremely subtle, but when integrated into grid compilation they could be used in assigning subordinate mating types (A1B2, A2B1).

Specimens examined, Lignomyces vetlinianus

POLAND, USTRZYKI DOLNE DIST., vic. Wetlina, 49°8′36″N, 22°29′5″E, Sep 1958, leg. & det. S. Domański, Flora Polonica No. 2337 (holotype; KRAM-F); Ustrzyki Dist., vic. Wetlina, Chryszczata Mountain, 10 Sep 1962, leg. M. Lisiewska, det. S. Domański, Flora Polonica No. 2338 (KRAM-F); Bieszezady, Hulski, 23 Aug 1965, leg. H.W. Wojewoda, det. S. Domański, Fungi Polonici No. 4695 (KRAM-F); Ustrzyki Dolne Dist., vic. Zatuanice, 22 Aug 1965, leg. S. Domański, Fungi Polonici No. 4618 (KRAM-F); Ustrzyki Dolne Dist., vic. Zatuanice, 28 Aug 1965, leg. S. Domański, Fungi Polonici No. 4778 (KRAM-F); Magurski National Park (Magurski Park Narodowy), N49°31′, E21°31′, 31.VII.2014, coll. & det. Piotr Chachuła, s.n. (KRAM-F, fragment TENN 69285). RUSSIA, MOSCOW REGION, Zvenigorod, vic. biostation of MSU, way from Sharapovshoe Swamp, 55°40′53.2″N, 36°44′25″E. 24 Aug 2008, spruce forest, on Populus tremula, leg. N. Psurtseva, det I. Zmitrovich (as Phyllotopsis nidulans), LE 265212 (culture as LE-BIN 2335); Zvenigorod, vic. Biological Station of Moscow State University, left side of road to Sharapov Swamp, 55°40′53.2″N, 36°44′25″E, spruce forest, on Populus tremula, 24 Aug 2008, leg. N. Psurtseva, det. O. Morozova (as Phyllotopsis nidulans), LE 254591 (culture as LE-BIN 2339); NOVGOROD REG., Malovisherskyi Distr. (Malaya Vishera), vic. Syis’ka (Syuyska), 58°47.276′N, 32°18.978′E, 16 Jul 2012, coll. S. Arslanov, ASN-2012-25 (LE 287743); Malovisherskyi Distr. (Malaya Vishera), vic. Syis’ka (Syuyska), 58°46.593′N, 32°18.735′E, 19 Jul 2012, coll. S. Arslanov, ASN-2012-51 (LE 287742); Malovisherskyi Distr. (Malaya Vishera), vic. Syis’ka (Syuyska), 58°46.482′N, 32°19.550′E, 29 Jun 2014, coll. S. Arslanov, LE 287550 (culture as LE-BIN 3253).

Specimens of Lignomyces vetlinianus extant but not examined

POLAND, USTRZYK DIST. vic. Wetlina, 49°8′36″N, 22°29′5″E, Aug 1962, leg. M. Lisiewska (cited by Domanski); Hnatove Berdo near Wetlina, 2 Oct 1967, leg. M. Moser, No. 67/237 (IB; not seen); vic. Tälchenes, southwest of the pass between Wetlina and Brzegami, 21 Sep 1975, leg. M. Moser, No. 75/302 (IB; not seen). RUSSIA, NOVOGOROD REG., Malovisherskyi Distr. (Malaya Vishera), vic. Syis’ka (Syuyska), 58°46.593′N, 32°18.735′E, 25 Aug 2013, coll. S. Arslanov (photos, no specimens).

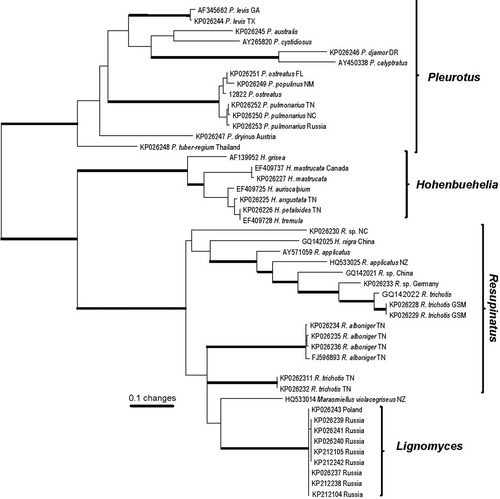

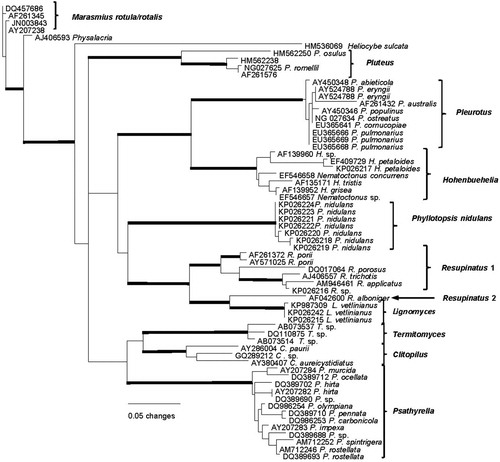

Phylogenetic analyses

The nrLSU phylogeny () contains diverse genera with pleurotoid basidiomata plus genera identified as potentially related by a BLAST query of GenBank. In this phylogeny the nearest sister group to Lignomyces is Resupinatus, but with Resupinatus appearing as polyphyletic. Close phylogenetic relationships of Lignomyces to Pleurotus and Hohenbuehelia are not supported in this or any other preliminary analysis that was performed.

Fig. 18. PhyML analysis based on the 59 nuclear ribosomal LSU region. Boldface lines indicate bootstrap support greater than 90%.

At the nrITS resolution () a single species, originally described as Resupinatus violaceogriseus CitationStevenson (1964) but transferred to Marasmiellus by CitationHorak (1971), appears as sister to Lignomyces sequences. Available descriptive material on this taxon (see virtualmycota.landcareresearch.co.nz/web-forms/vM_species_Details.aspx?pk=5732) indicates taxonomic separation of R. violaceogriseus from L. vetlinianus based (at least) on diverticulate pileus cuticle hyphae and cheilocystidia, as well as geographic distribution seemingly limited to New Zealand. In fact there are ample reasons to consider Resupinatus violaceogriseus as representing a separate and new genus.

Discussion

Originally identified in nature as Phyllotopsis nidulans, in situ or in vitro basidiomata did not exhibit the more vivid colors of pileus surface and lamellae of P. nidulans. Both preserved Russian specimens (LE 254591, LE 265212, LE 287550) now consist of slices of dried basidiomata of which pilei and stipes have dried adequately. Lamellae have dried somewhat cartilaginous and close to “cinnamon” (6B5) or “cinnamon buff” (6B4). KRAM-F specimens 4618 and 4696 consist of whole basidiomata that compare well to those illustrated ().

A phylogeny based on nrLSU () indicates Resupinatus alboniger (Pat.) Singer as sister lineage at this coarse resolution. CitationThorn (1986) furnished a thorough description and illustrations of R. alboniger based on numerous specimens from North America and Europe. While spore statistics and basidial dimensions resemble those of L. vetlinianus, cheilocystidia (usually branched or diverticulate) and pileipellis structure (thick-walled tortuous cuticle) appear significantly different. Basidiomata, as might be expected, are diminutive and pileus trama is gelatinized. In fact this nrLSU phylogeny might question placement of Resupinatus alboniger in core Resupinatus.

Of some ecological interest is the report of Lignomyces in Poland seemingly restricted to Fagus and from Russia as occurring on Populus. Although both genera belong in the Fagaceae, there is real possibility that the fungus actually occurs on at least these two hosts as well as others. In Poland the fungus has been endemic and of ecological interest (www.karpacki.eu/english_bieszczady.html). Conversely the Carpathian Mountains in which the Polish specimens were collected seem geologically unconnected with the widespread locations of Russian collections. Future collections could be expected from Ukraine and Belarus.

Domański described basidiospores as “saepe minutis irregularibusque granulis substantiae gelatinoae tecta”, but examination of his material indicates that refringent guttules might have obscured visualization of the thin, smooth spore wall.

Drawing attention to similarities of his Pleurotus vetlinianus to Hohenbuehelia, Domański compared his fungus to Hohenbuehelia atrocaerulea (Fr.) Singer and H. mastrucata (Fr.) Singer. Basidiomata of the first were more robust than any Hohenbuehelia ones. Moreover, basidiomata of Resupinatus Nees ex Gray were too small to be compared with those of Pleurotus vetlinianus, and those of both genera commonly produced cystidia of significantly different size and shape from those of P. vetlinianus.

Development of hymenium of in vitro basidiomata resembles that of Pleurocybella. Youngest basidiomata have a smooth hymenial surface. Basidiomata are pseudostipitate and in that regard resemble Campanophyllum proboscideum as well as basidiomata of some species of Hohenbuehelia, Lentinellus and Resupinatus.

Tetrapolarity was to be expected only because members of phylogenetically neighboring genera are dominated by such a mating system. Pleurotus appears uniformly tetrapolar (Petersen 1995). According to CitationThorn and Barron (1986; see also Petersen 1995), the species of Hohenbuehelia for which mating systems are known (Hohenbuehelia angustata, H. atrocoerulea) are bipolar, supported by data from our self-cross experiments (Petersen unpubl). Conversely some Resupinatus species (R. alboniger, R. striatulus) have been shown to be tetrapolar (CitationThorn and Barron 1986).

Growth rate and culture morphology of strains differed by media. The culture growth and the texture of the mycelium mat of Lignomyces strains on BWA medium were more vigorous in comparison with those on MEA where mycelium grew quickly but was thin and almost transparent and PDA where the growth rate was much lower.

The chemical nature of numerous crystals produced by the strains in vitro remains unknown, but they may relate to cyclic compounds revealed by the Wieland test forming colored substances with aromatic aldehydes liberated by the strong acid acting on lignin contained in newspaper. This test is often used to detect toxic fungal ama- and phallotoxins, but similar reactions give other cyclic compounds like psilocybin or indoles, terpenes, etcetera, which are non-toxic. Thus although the Wieland test was strongly positive we cannot conclude that the Lignomyces cultures contain any poisonous compounds.

umyc_a_11831589_sm0001.docx

Download MS Word (21.1 KB)Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Anna Ronikier (KRAM) for facilitating herbarium loan of Domański specimens and the 2014 Chachuła collection, which allowed sequencing and accurate microscopy. This project was supported in part by NSF DEB 1144974 to RHP and KH and by RFBR, research project No. 15-04-06211-a to NP.

Literature Cited

- FedorovaTVShakhovaNVKlyainOIGlazunovaOAMaloshenokLGKulikovaNAPsurtsevaNVKorolevaOV. 2013. Comparative analysis of the ligninolytic potential of Basidiomycetes belonging to different taxonomic and ecological groups. Appl Biochem Microbiol 49:570–580, doi:10.1134/s0003683813060082

- GCG. 2000. Wisconsin package 10.3. San Diego, California: Accelrys Inc.

- Geneious. 2005. Geneious 6.1.6 created by Biomatters. Available from http://www.geneious.com/

- HorakE. 1971. A contribution toward the revision of the Agaricales (fungi) from New Zealand. NZ J Bot 9:459–462, doi:10.1080/0028825X.1971.10430193

- HughesKWPetersenRHLodgeDJBergemannSEBaumgartnerKTullossRELickeyECifuentesJ. 2013. Evolutionary consequences of putative intra- and interspecific hybridization in agaric fungi. Mycologia 105:1577–1594, doi:10.3852/13-041

- KatohKMisawaKKumaKiMiyataT. 2002. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res 30: 3059–3066, doi:10.1093/nar/gkf436

- KornerupAWanscherJH. 1967. Methuen handbook of colour. 2nd ed. London: Methuen & Co. 243 p.

- MarrCD. 1979. Laccase and tyrosinase oxidation of spot test reagents. Mycotaxon 9:244–276.

- MoserM. 1979. Über einige neue odor seltene Agaricales-Arten aus dem Pieniny und aus Biesczciade, Polen. Sydowia (Ser 2) 8:268–275.

- PetersenRH. Contributions of mating studies to mushrooms systematics. Can J Bot 73 (Supple.1). S831–S842, doi: 10.1139/b95-329

- RidgwayR. 1912. Color standards and color nomenclature. Washington, DC: Publ. Priv. 43 p.

- StevensonG. 1964. The Agaricales of New Zealand V. Kew Bull 19:1–59, doi:10.2307/4108283

- ThornRG. 1986. The “Pleurotus silvanus” complex. Mycotaxon 25:27–66.

- ThornRGBarronGL. 1986. Nematoctonus and the tribe Resupinatae in Ontario, Canada. Mycotaxon 25:321–454.

- WielandT. 1986. Peptides of poisonous Amanita mushrooms. Springer Series in Molecular Biology. New York: Springer-Verlag. 256 p. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-71295-1